Blog Archives

Eddington (2025)

I’ve read more than a few searing indictments about writer/director Ari Aster’s latest film, Eddington, an alienating and self-indulgent movie starring Joaquin Phoenix on the heels of his last alienating and self-indulgent movie starring Phoenix. It’s ostensibly billed as a “COVID-era Western,” and that is true, but it’s much more than that. I can understand anyone’s general hesitation to revisit this acrimonious time, but that’s where the “too early yet too late” criticism of others doesn’t ring true for me. It is about that summer of 2020 and the confusion and anger and anxiety of the time; however, I view Eddington having more to say about our way of life in 2025 than looking back to COVID lockdowns and mask mandates. This is a movie about the way we live now and it’s justifiably upsetting because that’s where the larger culture appears to be at the present: fragmented, contentious, suspicious, and potentially irrevocable.

Eddington is a small-town in the dusty hills of New Mexico, neighboring a Pueblo reservation, and it serves as a tinderbox ready to explode from the tension exacerbated from COVID. Sheriff Joe Cross (Phoenix) has had it up to here with mask mandates and social distancing and the overall attitude of the town’s mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal). Joe decides to run for mayor himself on a platform of common-sense change, but nothing in the summer of 2020 was common.

Eddington is a movie with a lot of tones and a lot of ideas, and much like 2023’s Beau is Afraid, it’s all over the place with mixed results that don’t fully come together for a coherent thesis. However, that doesn’t deny the power to these indefatigable moments that stick with you long after. That’s an aspect of Aster movies: he finds a way to get under your skin, and while you may very well not appreciate the experience because it’s intentionally uncomfortable and probing, it sticks with you and forces you to continue thinking over its ideas and creative choices. It’s art that defiantly refuses to be forgotten. With that being said, one of the stronger aspects of Aster’s movies is his pitch-black sense of comedy that borders on sneering cynicism that can attach itself to everything and everyone. There are a lot of targets in this movie, notably conspiracy-minded individuals who want people to “do their own research,” albeit research ignoring verified and trained professionals with decades of experience and knowledge. There’s a lot of people talking at one another or past one another but not with one another; active listening is sorely missing, as routinely evidenced by the silences that accompany the mentally-ill homeless man in town that nobody wants to actively help because they see him as an uncomfortable and loud nuisance. For me, this is indicative of 2025, with people rapidly talking past one another rather than wanting to be heard.

When Aster is poking fun at the earnestness of the high school and college students protesting against police brutality, I don’t think he’s saying these younger adults are stupid for wanting social change. He’s ribbing how transparently these characters want to earn social cache for being outspoken. It’s what defines the character of Brian, just a normal kid who is so eager to be accepted that he lectures his white family on the tenets of destroying their own white-ness at the dinner table, to their decidedly unenthusiastic response. I don’t feel like Aster is saying these kids are phony or their message is misapplied or ridiculous or without merit. It’s just another example of people using fractious social and political issues as a launching point to air grievances rather than solutions. The protestors, mostly white, will work themselves into a furious verbal lather and then say, “This shouldn’t even be my platform to speak. I don’t deserve to tell you what to do,” and rather than undercutting the message, after a few chuckles, it came across to me like the desperation to connect and belong coming out. They all want to say the right combination of words to be admired, and Brian is still finding out what that might be, and his ultimate character arc proves that it wasn’t about ideological fidelity for him but opportunism. The very advancement of Brian by the end is itself its own indictment on white privilege, but you won’t have a character hyperventilating about it to underline the point. It’s just there for you to deliberate.

Along these lines, there’s a very curious inclusion of a trigger-happy group in the second half of the movie that blends conspiracy fantasy into skewed reality, and it begs further unpacking. I don’t honestly know what Aster is attempting to say, as it seems like such a bizarre inclusion that really upends our own understanding of the way the world works, and maybe that’s the real point. Maybe what Aster is going for is attempting to shake us out of our own comfortable understanding of the universe, to question the permeability of fact and fiction. Maybe we’re supposed to feel as dizzy and confused as the residents of Eddington trying to hold onto their bearings during this chaotic and significant summer of 2020.

I think there’s an interesting rejection of reality on display with Eddington, where characters are trying to square news and compartmentalize themselves from the proximity of this world. Joe Cross repeatedly dismisses the pandemic as something happening “out there.” He says there is no COVID in Eddington. For him, it’s someone else’s problem, which is why following prevailing health guidelines and mandates irks him so. It’s the same when he’s trying to explain his department’s response to the Black Lives Matter protests that summer in response to George Floyd’s heinous murder. To him, these kinds of things don’t happen here, the people of Eddington are excluded from the social upheaval. This is an extension of the “it won’t happen to me” denialism that can tempt any person into deluding ourselves into false security. It’s this kind of rationalization that also made a large-scale health response so burdensome because it asked every citizen to take up the charge regardless of their immediate danger for the benefit of others they will never see. For Joe, the tumult that is ensnaring the rest of the country is outside the walls of Eddington. It’s a recap on a screen and not his reality. Except it is his reality, and the movie becomes an indictment about pretending you are disconnected from larger society. It’s easier to throw up your hands and say, “Not me,” but it’s hard work to acknowledge the troubles of our times and our own engagement and responsibilities. In 2025, this seems even more relevant in our doom-scrolling era of Trump 2.0 where the Real World feels a little less real every ensuing day. It’s all too easy to create that same disassociation and say, “That’s not here,” but like an invisible airborne virus not beholden to boundaries and demarcations, it’s only a matter of time that it finds your doorstep too.

You may assume with its star-studded cast that this will be an ensemble with competing storylines, but it’s really Joe Cross as our lead from start to finish, with the other characters reflections of his stress. I won’t say that most of the name actors are wasted, like Emma Stone as Joe’s troubled wife and Austin Butler as a charismatic conman pushing repressed memory child-trafficking conspiracies, because every person is a reflection over what Joe Cross wants to be and is struggling over. Despite his flaws and some startling character turns, Aster has great empathy for his protagonist, a man holding onto his authority to provide a sense of connectivity he’s missing at home. Our first moment with this man is watching him listen to a YouTube self-help video on dealing with the grief of wanting children when your spouse does not. Right away, we already know there’s a hidden wealth of pain and disappointment here, but again Aster chooses empathy rather than easy villainy, as we learn his wife is struggling with PTSD and depression likely as a result of her own father’s potential molestation. This revelation can serve as a guide for the rest of the characters, that no matter their exterior selves that can demonstrate cruelty and absurdism, deep down many are processing a private pain that is playing out through different and often contentious means of survival. I don’t think Aster condones Joe Cross’ perspective nor his actions in the second half, but I do think he wants us to see Joe Cross as more than just some rube angry with lockdown because he’s selfish.

It’s paradoxical but there are scenes that work so splendidly while the movie as a whole can seem overburdened and far too long. The cinematography by the legendary Darius Khnodji (Seven, City of Lost Children) expertly frames and lights each moment, many of them surprising, intriguing, revealing, or shocking. There can be turns that feel sudden and jarring, that catapult the movie into a different genre entirely, into a Hitchcockian thriller where we know exactly what the reference point is that I won’t spoil, to an all-out action showdown popularized by Westerns. Beyond Aster’s general more-is-more preference, I think he’s dabbling with the different genres to not just goose his movie but to question our associations with those genres and our broader understanding of them. It’s not quite as clean as a straight deconstructionist take on familiar archetypes and tropes. It’s more deconstructing our feelings. Are we all of a sudden in a forgiving mood because the movie presents Joe as a one-man army against powerful forces? It’s all-too easy to get caught up in the rush of tension and satisfying violence and root for Joe, but should we? Is he a hero just because he’s out-manned? Likewise, with the conclusion, do we have pity for these people or contempt? I don’t know, though there isn’t much hope for the future of Eddington, and depressingly perhaps for the rest of us, so maybe all we have are those fleeting moments of awe to hold onto and call our own.

Eddington is an intriguing indictment about our modern culture and the rifts that have only grown into insurmountable chasms since the COVID-19 outbreak. It’s a Western in form pitting the figure of the law against the moneyed establishment, and especially its showdown-at-the-corral climax, but it’s also not. It’s a drama about people in pain looking for answers and connections but finding dead-ends, but it’s also not. It’s an absurdist dark comedy about dumb people making dumb and self-destructive decisions, but it’s also not. The paranoia of our age is leading to a silo-ing of information dissemination, where people are becoming incapable of even agreeing on present reality, where our elected leaders are drowning out the reality they don’t want voters to know with their preferred, self-serving fantasy, and if they just say it long enough, then a vulnerable populace will start to conflate fact and fiction. I don’t know what the solution here is, and I don’t think Aster knows either by the end of Eddington. I can completely understand people not wanting to experience a movie with these kinds of uncomfortable and relevant questions, but if you want to have a closer understanding of how exactly we got here, then Eddington is an artifact of our sad, stupid, and supremely contentious times. Don’t be like Joe and ignore what’s coming until it’s too late.

Nate’s Grade: B

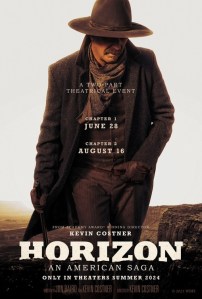

Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 (2024)

I admire Kevin Costner throwing out all the stops to achieve his passion, a four-part, twelve-hour film series to showcase a sprawling Western epic. The man put a hundred million of his own money into the first two parts of Horizon: An American Saga, and the time devoted to this project was so all-consuming that Costner quit the Yellowstone series, a cable TV juggernaut getting bigger ratings every season. It’s ballsy all right, to abandon a monumentally successful series at the height of its zeitgeist popularity so he can direct not just one but four throwback Westerns that will ultimately be as long as the Lord of the Rings trilogy. It’s rare to see this level of sheer chutzpah in Hollywood. Horizon’s first part was released in June, with its completed second part intended to be released a mere two months later in August. After the poor box-office of Part One, the studio decided to pull Part Two from the release schedule, ostensibly to give people more time to catch the first movie. Will we ever see Part Two in theaters? Will we ever see Part Three, which Costner is currently filming, or Part Four, which Costner is currently raising money for? Costner intended to release the whole saga as a miniseries upon completion, and this might be the best case scenario. As a movie, albeit one quarter of an intended whole, Horizon Part One feels far more structured as an incomplete and rather prosaic TV series.

Upon the completion of the 170 minutes, I was left wondering what was here that would make someone want to come back for a lengthy second part, let alone a third and a fourth. It doesn’t feel like a complete movie or even a completed chapter, and again let me cite Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series. Released over the course of three years, each movie had its own form of a beginning, middle, and end, with each climaxing around some event that left one satisfied by its conclusion. They didn’t just feel like chapters linking to the next; they felt like completed stories that pushed forward a larger overall story. Now, with Horizon Part One, it doesn’t feel like a three-hour movie, rather like three one-hour episodes of a TV series. Each of those hours feels too separate from the other. I’m reminded of television in the streaming era, where producers anticipate viewers binging through multiple episodes in speedy succession. This tacit assumption lends itself toward the general pacing issues I find with too many streaming series, where the filmmakers take far too long to get things moving in a significant manner. I’m reminded of a joke by Topher Florence that back in the day a show like Surf Dracula would feature its lead character surfing in weekly adventures, but the streaming age version would take its entire first season showing how he got his surfboard and then spend five minutes surfing in the finale. When you’re pacing out only one quarter of your possible intended story, calling it slow and lacking development and payoffs is an obvious hazard, which is why every movie needs to be its own thing, to provide a sense of conclusion even if it’s not the final conclusion.

Part One is divided into three parts: 1) the early settlers of Horizon, in the San Pedro Valley, being massacred by the Apache, 2) an old gunslinger (Kevin Costner) tasked with protecting a woman and child on the run from vengeful gunmen, 3) a wagon train of settlers headed to Horizon. Now, from that very streamlined synopsis, which of those storylines sounds the most exciting? Which of those storylines sounds like it can lend itself toward having an in-movie climax? Which of these storylines feels the most fraught with danger and intrigue? It’s the one starring Costner himself, of course, fitting naturally into the role of a tough curmudgeon.

I’m confused why the entire first hour of this movie is devoted to following the frontier town when we’re only going to get two survivors total that go forward. As far as its narrative importance, this entire section could have been condensed to a terrifying flashback from Frances Kittredge (Sienna Miller) and her daughter after the fact. The majority of this hour is spent watching the fine Christian folk of the early days of Horizon die horribly. We’re confined inside the battered Kittredge home that serves as the foundation of a siege thriller, with the band of various townspeople trapped and trying to fight off their indigenous intruders. The attack is prolonged and unsparing in its violence, eliminating all these nice, smiling faces from before. What does it add up to? It’s the tragic back-story for Frances, but it also makes her conveniently romantically unattached so that the nice cavalryman, Trent Gephart (Sam Worthington), can swoon and she can Learn to Love Again. It also sets up a young Apache warrior, Pionsenay (Owen Crow Shoe), making aggressive moves that his elders disagree with in their continued efforts to find some balance with the American settlers grabbing their territory. It also sets up what serves as the only possible character arc completion, with young Russell (Etienne Kellici) escaping the massacre in the beginning to then witness a massacre of Apache, and as he observes the scalping butchery, it galls him, not providing the relief of vengeance he had sought. Now that’s a conceivably emotional storyline, but Russell isn’t the primary character, or even one of the most essential supporting characters. You might genuinely forget about him like I did.

Something else I forgot an hour in was that Part One opens with Ellen Harvey (Jena Malone) shooting her abusive husband and running out. This prologue eventually comes back to setting up the present-day conflicts of the second hour, where Ellen has started a new life as Lucy with her young son. She lives in the Wyoming territory with a prostitute, Marigold (Abbey Lee). This storyline picks up significantly with new characters coming into the mix and disrupting the status quo. The first is Hayes Ellison (Costner) who finds himself attracted to Marigold, perhaps recognizing a woman in over her head. The second are the Sykes brothers (Jamie Campebell Bower, Jon Beavers) who have come looking to retrieve Lucy and her child, the son of their dearly departed pa who was slain in the opening. I am astounded that Costner decided to make the audience wait an hour for this segment because it feels like a much better fit to open Part One. There’s an immediacy to the looming danger and the consequences of actions, and what would serve as the Act One break is when Hayes has to intervene at great risk. This is, by far, the best segment of Horizon Part One. The ensuing on-the-run segment doesn’t get much further, setting up ongoing antagonism between the two sides that presumably will come to blows again. It’s not exactly reinventing the wagon wheel here: drifter reluctantly becoming protector for the vulnerable and reckoning with his shady past and trying to make amends. However, for this first movie, at least this storyline provides a sustained level of engagement with needed urgency.

The weakest portion is the wagon train led by Matthew Van Weyden (Luke Wilson). The most significant conflict during this section isn’t even the protection of the wagon train, it’s whether or not the hoity-toity British couple (Tom Payne, Anna and the Apocalypse‘s Ella Hunt) will assimilate to life on the prairie. They’re privileged, though at least he seems to recognize this. She bathes in the drinking water supply in an extended sponge bath sequence that feels so oddly gratuitous and leery. Two scouts are caught eagerly peeping and this seems like the most significant conflict of this whole section. They’re headed for Horizon, the setting of tragedy and indigenous conflict we know, but the entire wagon train lacks any feeling of dread or even the opposite, a feeling of yearning for a new life. It’s just a literal pileup of underwritten characters in movement without giving us a reason to care.

Costner’s Western eschews the trappings of modern revisionism, deconstructing the heroism and Manifest Destiny mythology of popular Wild West media. This isn’t a deconstruction but a full blown romantic classical Western, embracing the tropes with stone-faced gusto. In some ways it feels like Costner’s version of a Taylor Sheridan show (1883, Yellowstone). He left a Sheridan show to make his own Sheridan show. It’s more measured in its portrayal of the Native Americans even as it shows them massacring men, women, and children as our first impression. I wager Costner is showing that the evils of violent tendencies pervade both sides of the conflict, with a troop of American scalp-hunters that don’t really care where those scalps come from. It’s hard to fully articulate the themes given this is only one-fourth of the overall intended picture. The expansive settings are stunning and gorgeously filmed. I can understand why Costner would want people to watch this movie on the big screen with scenery this beautiful from cinematographer J. Michael Muro, who served as Costner’s DP on 2003’s Open Range, another muscular Western. Fun fact: Muro also served as a Steadicam operator on Costner’s Best Picture-winning Dances with Wolves, so their professional relationship goes back thirty-five years and covers Costner’s love affair with Westerns.

During its conclusion, Horizon: An American Saga runs through a wordless montage of clips that serves as a trailer for the forthcoming Part Two. It’s not edited like a trailer, more so a very leisurely preview with clips that look good but, absent context, can be shrug-worthy. Oh look, a character looking out a window pensively. Oh look, a character walking along a trail. Oh look, a character dismounting from a horse. Oh look, another character looking out a window pensively. It’s hard for me to fathom this truncated preview getting too many people excited for what Part Two has to offer, but then I think that’s the same problem with Part One. It doesn’t serve as a grabber, with characters we really care about, with conflicts that keep us glued, and with revelations and character turns that can keep us intrigued and desperately wanting more. It’s hard for me to think of that many people walking out of Part One and being ravenous for nine more hours. I accept that stories might feel incomplete and characters might feel disjointed, but Horizon is perhaps a Western best left in the distance, at least until you can binge it in its completed form, whatever that may be, though I doubt we’re going to get four full movies. Ultimately, Costner’s opus will need to be judged as a whole rather than as consecutive parts.

Nate’s Grade: C

The Power of the Dog (2021)

Every year, it seems that Netflix’s crown jewel for their big Oscar hopes ends up getting marvelous critical acclaim, and then when I finally watch it I am left disappointed. It happened in 2018 with Roma. It happened in 2019 with The Irishman. And it happened in 2020 with Mank. I haven’t disliked any of those movies, but I was unable to see the highly laudable merits as other critics. Now here comes their big Oscar play for 2021, Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, a Western that has been gracing the top of more critics lists than any other American film this year (I’ll be getting to you soon enough, Drive My Car). As I burned through awards movie after awards movie to assess, I held back from The Power of the Dog for a time. I just didn’t want to find that once again I was disappointed with the latest Netflix Oscar contender. I’m still chewing over my feelings with The Power of the Dog, which has a lot going on under the surface and a palpable tension that you’re unsure of how and when it will erupt. It’s also a movie that touches upon repression, toxic masculinity, manifest destiny, grooming, emotional and physical manipulation, and the danger of unstable men who are unable to process who they really are.

Every year, it seems that Netflix’s crown jewel for their big Oscar hopes ends up getting marvelous critical acclaim, and then when I finally watch it I am left disappointed. It happened in 2018 with Roma. It happened in 2019 with The Irishman. And it happened in 2020 with Mank. I haven’t disliked any of those movies, but I was unable to see the highly laudable merits as other critics. Now here comes their big Oscar play for 2021, Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, a Western that has been gracing the top of more critics lists than any other American film this year (I’ll be getting to you soon enough, Drive My Car). As I burned through awards movie after awards movie to assess, I held back from The Power of the Dog for a time. I just didn’t want to find that once again I was disappointed with the latest Netflix Oscar contender. I’m still chewing over my feelings with The Power of the Dog, which has a lot going on under the surface and a palpable tension that you’re unsure of how and when it will erupt. It’s also a movie that touches upon repression, toxic masculinity, manifest destiny, grooming, emotional and physical manipulation, and the danger of unstable men who are unable to process who they really are.

Set in 1925 Montana, Phil (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his brother George (Jessie Plemons) own and operate a cattle ranch. George marries a widow, Rose (Kirsten Dunst), and brings his new wife and her teenage son, Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) to live at the ranch. Phil resents his new sister-in-law, looks down on her son, and torments both repeatedly. Rose sees Phil as an enemy, someone who will not stop until he forces her out, and his target becomes her son, Peter.

This is less a traditional Western in several respects and more a tight character study that happens to be set at the conclusion of a Western fantasy for America, transitioning to modernity. It goes against our preconceived notions of a Western, not in a deliberately deconstructive way like 1992’s brilliant Best Picture, Unforgiven, but more in providing contrary thematic details that often get squeezed out. I was expecting the movie to take place maybe during the 1870s or 1880s, but the fact that it’s taking place five years removed from the Great Depression offers different story opportunities and larger reflection. There’s a reason this story is told well after the halcyon days of the Old Wild West. The movie is about certain characters holding onto an exclusive past that has eclipsed them and others ready to move forward by shuttling over their past and the obstacles standing in the way of personal progress.

This is less a traditional Western in several respects and more a tight character study that happens to be set at the conclusion of a Western fantasy for America, transitioning to modernity. It goes against our preconceived notions of a Western, not in a deliberately deconstructive way like 1992’s brilliant Best Picture, Unforgiven, but more in providing contrary thematic details that often get squeezed out. I was expecting the movie to take place maybe during the 1870s or 1880s, but the fact that it’s taking place five years removed from the Great Depression offers different story opportunities and larger reflection. There’s a reason this story is told well after the halcyon days of the Old Wild West. The movie is about certain characters holding onto an exclusive past that has eclipsed them and others ready to move forward by shuttling over their past and the obstacles standing in the way of personal progress.

There are thematic layers expertly braided together that touch upon the larger question over what it means to be a man in society. Each of the primary male characters (Phil, George, Peter) is an outsider to some degree, someone who doesn’t neatly fit into what constitutes a conventional man of the times. George is soft, empathetic, meek yet in a position of power from his family’s status; Peter is rail-thin, academic, odd, effeminate at turns, a dandy presented for ridicule; Phil is the one who presents as a “man’s man,” a hard-driving, hard-drinking man of the land who imposes his will on others. However, deep down, Phil is hiding a key part of himself that would conflict with his society’s view of masculinity. Each man bounces around points of conflict and connection with one another, familial bonds fraying, and a slow-burning battle for supremacy escalating.

The movie could have also been charitably nick-named “Benedict Cumberbatch is a jerk to everyone,” as this is much of what Campion’s script, based upon the 1957 novel by Thomas Savage consists of. The movie is absent a primary perspective. We drift from person to person in the small-scale ensemble, elevating this next character and their views and worries and priorities. Phil could be deemed the primary protagonist and antagonist, especially the latter. He’s a mean man. Phil is a man who likes to make others uncomfortable, who needles them, and he takes great interest in targeting Rose, partly because he doesn’t like the influence she has on his only brother, and partly because he can get away with it. When he sets his sights on Peter, you don’t quite know what this hostile man will do to get his way. Will he manipulate Peter to turn him from his mother? Will he endanger Peter as a threat to Rose? Will he go further and possibly kill Peter? Or, as becomes more evident, does he see Peter in a very different light, a special kinship that had defined Phil’s own secretive past.

The movie could have also been charitably nick-named “Benedict Cumberbatch is a jerk to everyone,” as this is much of what Campion’s script, based upon the 1957 novel by Thomas Savage consists of. The movie is absent a primary perspective. We drift from person to person in the small-scale ensemble, elevating this next character and their views and worries and priorities. Phil could be deemed the primary protagonist and antagonist, especially the latter. He’s a mean man. Phil is a man who likes to make others uncomfortable, who needles them, and he takes great interest in targeting Rose, partly because he doesn’t like the influence she has on his only brother, and partly because he can get away with it. When he sets his sights on Peter, you don’t quite know what this hostile man will do to get his way. Will he manipulate Peter to turn him from his mother? Will he endanger Peter as a threat to Rose? Will he go further and possibly kill Peter? Or, as becomes more evident, does he see Peter in a very different light, a special kinship that had defined Phil’s own secretive past.

I suppose it’s a spoiler to go further so if you want to, dear reader, then go ahead and skip to the next paragraph. Phil reveres “Bronco Henry,” a deceased rancher that taught him many things when he was younger. The movie heavily, heavily implies that this long-departed older man had a romantic relationship with Phil when he was much younger, something the grown Phil cherishes, caressing himself in private with a scrap of fabric belonging to Henry. The lazy characterization would be, “Oh, Phil is homophobic because he’s really gay, and he’s angry because he cannot accept himself.” With Campion, Phil could be viewed as a victim too. He was likely groomed by an older man, and maybe that relationship was viewed by Phil as more romantic and consensual than it was, but it’s the lingering nostalgic memory of the intimate happiness that he holds onto, afraid to move on because of the danger of letting go and the danger of possibly reaching out, being vulnerable again. Yes, dear reader, this is more a gay cowboy movie than Brokeback Mountain (which, to be fair, were sheep herders). Savage himself was also gay. As Phil takes Peter under his wing, you don’t know whether this man is going to kill or kiss him, and the tension is ripe enough that either way it can ties you up into anxious knots.

The acting is extremely polished all around, with each performer having layers of subtext to shield their true intentions. Cumberbatch (Spider-Man: No Way Home) is a thorn in so many sides and it isn’t until much later that the veil begins to drop, ever so slightly, allowing you to finally see extra dimension with what appears to be a bully character for so long. He might just be too impenetrable for too long for some viewers to develop any empathy. Plemons (Jungle Cruise) and Dunst (Melancholia) are sweet together, and I enjoyed how each one leans upon the other for support. Rose is the butt of much of Phil’s torment and teasing, so we watch Dunst break down under the constant abuse of her berating brother-in-law. When her character sees a way to gain an upper hand, it becomes like a light in the darkness for her momentary relief. I felt heartbroken for Rose as she studied a piano tune for weeks to impress esteemed guests of her husband’s, only to succumb to her nerves and insist she couldn’t play because she didn’t think she could be good enough. Then to watch Phil cruelly needle her further about her disappointment by whistling that same tune is even worse. This is the best acting of Smit-McPhee (Let Me In) since he was vying with Asa Butterfield (Hugo, Ender’s Game) for every preteen lead in big studio features. There’s a deliberate standoffish quality to the character, to Peter’s way of viewing others. It’s like he’s part alien, studying the things that make people tick. Like Cumberbatch, there are multiple layers to this performance because his intentions are equally if not more guarded. You almost need to watch the movie a second time to better identify what Smith-McPhee is doing in scene after scene.

The Power of the Dog is a terrific looking and sounding movie. The photography is beautiful, the New Zealand landscapes are awe-inspiring, the production design is handsome, the musical score by Johnny Greenwood (There Will Be Blood) is discordant strings that enhances the tension permeating through the movie. Campion hasn’t directed a movie in over ten years, and this is only her second movie since 2003’s misbegotten erotic thriller, In the Cut, starring an against-type Meg Ryan. It feels like she’s had no time away with how controlled and resonant her directing plays. I wish her script was less ambiguous to a fault; it errs somewhat I believe by holding out key revelations about Phil for too long, leaving us with the man being an unrepentant bully for too long. There are significant turns in the concluding minutes that will reorient your interpretation of the entire film, and I have every reason to believe that when I watch The Power of the Dog another time it will be even more impressive.

The Power of the Dog is a terrific looking and sounding movie. The photography is beautiful, the New Zealand landscapes are awe-inspiring, the production design is handsome, the musical score by Johnny Greenwood (There Will Be Blood) is discordant strings that enhances the tension permeating through the movie. Campion hasn’t directed a movie in over ten years, and this is only her second movie since 2003’s misbegotten erotic thriller, In the Cut, starring an against-type Meg Ryan. It feels like she’s had no time away with how controlled and resonant her directing plays. I wish her script was less ambiguous to a fault; it errs somewhat I believe by holding out key revelations about Phil for too long, leaving us with the man being an unrepentant bully for too long. There are significant turns in the concluding minutes that will reorient your interpretation of the entire film, and I have every reason to believe that when I watch The Power of the Dog another time it will be even more impressive.

Congratulations, Netflix, on breaking your streak of disappointing me with your prized awards contenders. I’ve included many Netflix movies in my best lists, and worst lists, over the years, as that is the lot when you have such an enormous library in the prestige streaming arms race. The Power of the Dog is an intimate and occasionally even sensual Western that pushes its put-upon characters to their breaking point, and perhaps the audience, while rewarding the patient and observant viewer. There’s gnawing, uneasy tension that gets to be overwhelming, but the movie benefits from the unexpected destination for where that tension will lead. Will it be violence? Will it be passion? Will it be a crime of passion? The acting is great, the artistic quality of the movie is high, and each scene has much to unpack, allowing for further rewarding examination. I wish there was more of the last half hour when things better come into sharper focus, and I wish the movie was a little less ambiguous for so long, but this is one of the better films of 2021 and Campion’s best movie since 1993’s The Piano (I fully expect her to become the first female director nominated twice for the Best Director Oscar). The Power of the Dog is a lyrical, surprising drama, a sneaky character study, and proof that my Netflix overrated front-runner curse has been lifted (for now).

Nate’s Grade: A-

News of the World (2020)

News of the World is an old-fashioned story, a Western and road movie, a grieving father taking a young girl under his wing, but with a slight modern polish thanks to the cinema verite style of director Paul Greengrass (The Bourne Supremacy, Captain Phillips). The handheld camerawork and close-ups create a different kind of mood for a genre defined by long takes of sterling vistas. Hanks plays Captain Kidd, a traveling performer in 1870 who would literally collect newspapers and read the news to the locals, providing a wider understanding of the wider world. Along the way he comes across a young German girl (Helena Zengel) who was raised by a Native American tribe (the same tribe killed her German family and adopted her). He is determined to take her to the last of her family 400 miles away and from there they encounter many dangers and detours. I feel like every big filmmaker at some point feels the need to make a Western, and now Greengrass has scratched that itch. The older genre is so mythic and filled with grandly romantic notions of the frontier. News of the World is more an old-fashioned Western, without much in the way of critique, and fairly episodic in plot, and Kidd and the kid travel from miniature set piece to set piece like little narrative cul-de-sacs rarely producing additional connections from their adventures. I hoped Greengrass would bring his docu-drama realism to deconstruct the American romanticism of the Wild West, pick apart at that myth-making and whitewashing, but the movie is more committed to being a safe, square, and traditional old movie. The little girl is less a character and more of a necessary plot device, something to drive this man to confront his grief and provide a purpose for him. I wish there was more to their dynamic but she could have just as easily been replaced with a dog. There is one shootout that serves as the highlight of the film and where Greengrass comes most alive with his sense of tension. I was expecting a bit more conflict or commentary given that Kidd is traveling post-Civil War Southwest and selecting what news each community wants to hear, tailoring to his audience and knowing everyone likes a good story during “these troubled times.” There’s one section where a local boss looks to take advantage of Kidd’s services by forcing him to read from the boss’ propaganda publication and Kidd turns the tables on him. It feels like an anecdote rather than a thesis statement. I kept waiting for more to arise with the characterization but was left disappointed, as much of the movie is kept at a surface-level of who these people are. Whether it’s victim, saint, marauder, or newsman, everyone is pretty much whom you assume on first impression. The movie’s staid pacing lingers. It’s two hours but it’s not in any sense of hurry. Part of this is because the screenplay, based upon a 2016 book by the same name, is entirely predictable. Even the revelations held until the very end for fitting tragic character back-stories can be sussed out. I watched News of the World and kept thinking, “What about this story got these people so excited?” I think it was Greengrass feeling that artistic itch to lend his stamp on the American Western (I was reminded of Ron Howard’s own itch, 2003’s The Missing) and yet it feels like Greengrass was holding back and just sublimated his style to the settled genre expectations. It’s not a bad movie by any means but it lacks anything exceptional to demand a viewing. It’s a perfectly fine movie with a handsome production, gorgeous setting, effective score, and sturdy acting, and when it’s over you’ll say, “Well, that was fine,” and then you’ll go on with your life.

News of the World is an old-fashioned story, a Western and road movie, a grieving father taking a young girl under his wing, but with a slight modern polish thanks to the cinema verite style of director Paul Greengrass (The Bourne Supremacy, Captain Phillips). The handheld camerawork and close-ups create a different kind of mood for a genre defined by long takes of sterling vistas. Hanks plays Captain Kidd, a traveling performer in 1870 who would literally collect newspapers and read the news to the locals, providing a wider understanding of the wider world. Along the way he comes across a young German girl (Helena Zengel) who was raised by a Native American tribe (the same tribe killed her German family and adopted her). He is determined to take her to the last of her family 400 miles away and from there they encounter many dangers and detours. I feel like every big filmmaker at some point feels the need to make a Western, and now Greengrass has scratched that itch. The older genre is so mythic and filled with grandly romantic notions of the frontier. News of the World is more an old-fashioned Western, without much in the way of critique, and fairly episodic in plot, and Kidd and the kid travel from miniature set piece to set piece like little narrative cul-de-sacs rarely producing additional connections from their adventures. I hoped Greengrass would bring his docu-drama realism to deconstruct the American romanticism of the Wild West, pick apart at that myth-making and whitewashing, but the movie is more committed to being a safe, square, and traditional old movie. The little girl is less a character and more of a necessary plot device, something to drive this man to confront his grief and provide a purpose for him. I wish there was more to their dynamic but she could have just as easily been replaced with a dog. There is one shootout that serves as the highlight of the film and where Greengrass comes most alive with his sense of tension. I was expecting a bit more conflict or commentary given that Kidd is traveling post-Civil War Southwest and selecting what news each community wants to hear, tailoring to his audience and knowing everyone likes a good story during “these troubled times.” There’s one section where a local boss looks to take advantage of Kidd’s services by forcing him to read from the boss’ propaganda publication and Kidd turns the tables on him. It feels like an anecdote rather than a thesis statement. I kept waiting for more to arise with the characterization but was left disappointed, as much of the movie is kept at a surface-level of who these people are. Whether it’s victim, saint, marauder, or newsman, everyone is pretty much whom you assume on first impression. The movie’s staid pacing lingers. It’s two hours but it’s not in any sense of hurry. Part of this is because the screenplay, based upon a 2016 book by the same name, is entirely predictable. Even the revelations held until the very end for fitting tragic character back-stories can be sussed out. I watched News of the World and kept thinking, “What about this story got these people so excited?” I think it was Greengrass feeling that artistic itch to lend his stamp on the American Western (I was reminded of Ron Howard’s own itch, 2003’s The Missing) and yet it feels like Greengrass was holding back and just sublimated his style to the settled genre expectations. It’s not a bad movie by any means but it lacks anything exceptional to demand a viewing. It’s a perfectly fine movie with a handsome production, gorgeous setting, effective score, and sturdy acting, and when it’s over you’ll say, “Well, that was fine,” and then you’ll go on with your life.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (2019)

Quentin Tarantino has been playing in the realm of genre filmmaking for much of the last twenty years. He’s made highly artful, Oscar-winning variations on B-movies and grindhouse exploitation pictures. There are some film fans that wished he would return to the time of the 90s where he was telling more personal, grounded stories. His ninth movie, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, is Tarantino returning to the landscape of his youth, the Hollywood back lots and television serials that gave birth to his budding imagination. Tarantino has said this is his most personal film and it’s easy to see as a love letter to his influences. It’s going to be a divisive movie with likely as many moviegoers finding it boring as others find it spellbinding.

In February 1969, actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) is struggling to recapture his past glory as a popular TV star from a decade prior. Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) is Rick’s longtime stuntman, personal driver, and possibly only real friend. Rick’s next-door neighbor happens to be Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie), a rising star and the wife to famed director Roman Polanski. All three are on a collision course with the Manson family.

The thing you must know before embarking into a theater to see all of the 160 minutes of Tarantino’s latest opus is that it’s the least plot-driven of all his movies, and it’s also in the least hurry. This feels like a hang-out movie through Tarantino’s memories of an older Hollywood that he grew up relishing. It’s very much a loving homage to the people who filled his head with dreams, with specific affection given to the life of an actor. Tarantino is exploring three different points of an actor’s journey through fame; Sharon Tate is the in-bloom star highly in demand, Rick Dalton is the one who has tasted fame but is hanging on as tightly as he can to his past image and wondering if he’s hit has-been status, and then there’s Cliff Booth who was a never-was, a replaceable man happy to be behind the scenes and who has met his lot in life with a Zen-like acceptance. Each character is at a different stage of the rise-and-fall trajectory of Hollywood fame and yet they remain there. This isn’t a movie where Rick starts in the dumps and turns his life around, or even where it goes from worse to worse. Each character kind of remains in a stasis, which will likely drive many people mad. It will feel like nothing of import is happening and that Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is more a collection of scenes than a whole.

The thing you must know before embarking into a theater to see all of the 160 minutes of Tarantino’s latest opus is that it’s the least plot-driven of all his movies, and it’s also in the least hurry. This feels like a hang-out movie through Tarantino’s memories of an older Hollywood that he grew up relishing. It’s very much a loving homage to the people who filled his head with dreams, with specific affection given to the life of an actor. Tarantino is exploring three different points of an actor’s journey through fame; Sharon Tate is the in-bloom star highly in demand, Rick Dalton is the one who has tasted fame but is hanging on as tightly as he can to his past image and wondering if he’s hit has-been status, and then there’s Cliff Booth who was a never-was, a replaceable man happy to be behind the scenes and who has met his lot in life with a Zen-like acceptance. Each character is at a different stage of the rise-and-fall trajectory of Hollywood fame and yet they remain there. This isn’t a movie where Rick starts in the dumps and turns his life around, or even where it goes from worse to worse. Each character kind of remains in a stasis, which will likely drive many people mad. It will feel like nothing of import is happening and that Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is more a collection of scenes than a whole.

What elevated the film was how much I enjoyed hanging out with these characters. Tarantino is such a strong storyteller that even when he’s just noodling around there are pleasures to be had. Tarantino movies have always favored a vignette approach, unwieldy scenes that serve as little mini movies with their own beginnings, middles, and often violently climactic ends. An excellent example of this is 2009’s Inglourious Basterds where the moments are brilliantly staged and developed while also serving to push the larger narrative forward. That’s missing with Hollywood, the sense of momentum with the characters. We’re spending time and getting to know them, watching them through various tasks and adventures over the course of two days on sets, at home, and on a former film set-turned-ranch for a strange commune. If you’re not enjoying the characters, there won’t be as much for you as a viewer, and I accept that. None of the central trio will crack Tarantino’s list for top characters, but each provides a different viewpoint in a different facet of the industry, though Sharon Tate is underutilized (more on that below). It’s a bit of glorified navel-gazing for Tarantino’s ode to Hollywood nostalgia. There are several inserts that simply exist to serve as silly inclusions that seem to be scratching a personal itch for the director, less the story. I was smiling at most and enjoyed the time because it felt like Tarantino’s affection translated from the screen. I enjoyed hanging out with these people as they explored the Hollywood of yesteryear.

DiCaprio hasn’t been in a movie since winning an Oscar for 2015’s The Revenant and he has been missed. His character is in a very vulnerable place as he’s slipping from the radars of producers and casting agents, filling a string of TV guest appearances as heavies to be bested by the new hero. He’s self-loathing, insecure, boastful, and struggling to reconcile what he may have permanently lost. Has he missed his moment? Is his time in the spotlight eclipsed? There’s a new breed of actors emerging, typified by a little girl who chooses to stay in character in between filming. Everything is about status, gaining it or losing it, and Rick is desperate. There’s a terrific stretch where he’s playing another heavy on another TV Western and you get the highs and lows, from him struggling to remember his lines and being ashamed by the embarrassment of his shaky professionalism, to showing off the talent he still has, if only given the right opportunity. DiCaprio is highly entertaining as he sputters and soars.

DiCaprio hasn’t been in a movie since winning an Oscar for 2015’s The Revenant and he has been missed. His character is in a very vulnerable place as he’s slipping from the radars of producers and casting agents, filling a string of TV guest appearances as heavies to be bested by the new hero. He’s self-loathing, insecure, boastful, and struggling to reconcile what he may have permanently lost. Has he missed his moment? Is his time in the spotlight eclipsed? There’s a new breed of actors emerging, typified by a little girl who chooses to stay in character in between filming. Everything is about status, gaining it or losing it, and Rick is desperate. There’s a terrific stretch where he’s playing another heavy on another TV Western and you get the highs and lows, from him struggling to remember his lines and being ashamed by the embarrassment of his shaky professionalism, to showing off the talent he still has, if only given the right opportunity. DiCaprio is highly entertaining as he sputters and soars.

The real star of the film is Pitt (The Big Short) playing a man who seems at supernatural ease no matter the circumstance. He’s got that unforced swagger of a man content with his life. He enjoys driving Rick around and providing support to his longtime friend and collaborator. He has a shady past where he may or may not have killed his wife on purpose, but regardless apparently he “got away with it.” This sinister back-story doesn’t seem to jibe with the persona we see onscreen, and maybe that’s the point, or maybe it’s merely a means to rouse suspicion whether he may become persuaded by the Manson family he visits later in the movie dropping off a hitchhiker he’s encountered all day long. The role of Cliff seems to coast on movie star cool. There is supreme enjoyment just watching Pitt be. Watch him feed his dog to a trained routine, watch him fix a broken TV antenna and show off his ageless abs, and watch him navigate trepidatious new territory even as others are trying to intimidate him. It’s Pitt’s movie as far as I’m concerned. He was the only character I felt nervous about when minimal danger presented itself. There’s something to be said that the best character is the unsung one meant to take the falls for others, the kind of back-breaking work that often goes unnoticed and unheralded to keep the movie illusion alive.

There aren’t that many surprises with Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood as it moseys at its own loping pace. It reminded me of a Robert Altman movie or even a Richard Linklater film. It’s definitely different from Tarantino’s more genre-fed excursions of the twenty-first century. It’s a softer movie without the undercurrent of malice and looming violence. There is the Manson family and Tarantino knows our knowledge of the Manson family so we’re waiting for their return and that fateful night in August, 1969 like a ticking clock. It wouldn’t be a Tarantino movie without an explosion of bloody violence as its climax, and he delivers again, but I was shocked how uproariously funny I found the ending. I laughed throughout but as the movie reached its conclusion I was doubled over with laughter and clapping along. There’s a flashback where Cliff and a young Bruce Lee challenge each other to a fight, and it’s so richly entertaining. The phony film clips are also a consistent hoot, especially when Rick goes to Italy. It’s a funnier movie than advertised and, despite its ending, a far less violent movie than his reputation.

As Tarantino’s memory collection, the level of loving homage can start to eat the narrative, and this is most noticeable with the handling of Sharon Tate. The initial worries that Tarantino would exploit the horrendous Manson murders for his own neo-pop pulp was unfounded. Tate is portrayed with empathy and compassion, and as played by Robbie she nearly glides through the film as if she were an angel gracing the rest of us unfortunate specimens. She has a great moment where she enters a movie theater playing a comedy she is a supporting player in. The camera focuses on Robbie’s (I,Tonya) face as an array of micro expressions flash as she takes in the approving laughter of the crowd. It’s a heartwarming moment. But all of that doesn’t make Tate a character. She’s more a symbol of promise, a young starlet with the world at her fingertips, the beginning phase of fame. Even the Manson clan doesn’t play much significance until the final act. Charles Manson is only witnessed in one fleeting scene. I thought Tarantino was including Tate in order to right a historical wrong and empower a victim into a champion, and that doesn’t quite happen. I won’t say further than that though her narrative significance is anticlimactic. You could have easily cut Sharon Tate completely out of this movie and not affected it much at all. In fact, given the 160-minute running time, that might have been a good idea. The movie never really comes to much of something, whether it’s a statement, whether it’s a definitive end, it just feels like we’ve run out of stories rather than crafted an ending that was fated to arrive given the preceding events.

As Tarantino’s memory collection, the level of loving homage can start to eat the narrative, and this is most noticeable with the handling of Sharon Tate. The initial worries that Tarantino would exploit the horrendous Manson murders for his own neo-pop pulp was unfounded. Tate is portrayed with empathy and compassion, and as played by Robbie she nearly glides through the film as if she were an angel gracing the rest of us unfortunate specimens. She has a great moment where she enters a movie theater playing a comedy she is a supporting player in. The camera focuses on Robbie’s (I,Tonya) face as an array of micro expressions flash as she takes in the approving laughter of the crowd. It’s a heartwarming moment. But all of that doesn’t make Tate a character. She’s more a symbol of promise, a young starlet with the world at her fingertips, the beginning phase of fame. Even the Manson clan doesn’t play much significance until the final act. Charles Manson is only witnessed in one fleeting scene. I thought Tarantino was including Tate in order to right a historical wrong and empower a victim into a champion, and that doesn’t quite happen. I won’t say further than that though her narrative significance is anticlimactic. You could have easily cut Sharon Tate completely out of this movie and not affected it much at all. In fact, given the 160-minute running time, that might have been a good idea. The movie never really comes to much of something, whether it’s a statement, whether it’s a definitive end, it just feels like we’ve run out of stories rather than crafted an ending that was fated to arrive given the preceding events.

The Tarantino foot fetish joke has long been an obvious and hacky criticism that I find too many people reach for to seem edgy or clever, so I haven’t mentioned it in other reviews. He does feature feet in his films but they’ve had purpose before, from arguing over the exact implications of a foot rub in Pulp Fiction to Uma Thurman commanding her big toe to wiggle and break years of entropy in Kill Bill. However, with Hollywood, it feels like Tarantino is now trolling his detractors. There are three separate sequences featuring women’s feet, two of which just casually place them right in the camera lens. At this point in his career, I know he knows this lame critique, and I feel like this is his response. It’s facetious feet displays.

When it comes to Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, if you’re not digging the vibe, man, then there’s less to latch onto as an audience member. It’s a definite hang-out movie reminiscent of Altman or Linklater where we watch characters go about their lives, providing peaks into a different world. It’s a movie about meandering but I always found it interesting or had faith that was rewarded by Tarantino. It doesn’t just feel like empty nostalgia masquerading as a movie. It’s funnier and more appealing than I thought it would be, and even though it’s 160 minutes it didn’t feel long. The acting by DiCaprio and Pitt is great, as is the general large ensemble featuring lots of familiar faces from Tarantino’s catalogue. I do think the inclusion of Sharon Tate serves more of a symbolic purpose than a narrative purpose and wish the movie had given her more to do or even illuminated her more as a character. However, the buddy film we get between DiCaprio and Pitt is plenty entertaining. It might not be as narratively ambitious or intricate or even as satisfying as Tarantino’s other works, but Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is a fable for a Hollywood that may have only existed in Tarantino’s mind, but he’s recreated it with uncompromising affection.

When it comes to Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood, if you’re not digging the vibe, man, then there’s less to latch onto as an audience member. It’s a definite hang-out movie reminiscent of Altman or Linklater where we watch characters go about their lives, providing peaks into a different world. It’s a movie about meandering but I always found it interesting or had faith that was rewarded by Tarantino. It doesn’t just feel like empty nostalgia masquerading as a movie. It’s funnier and more appealing than I thought it would be, and even though it’s 160 minutes it didn’t feel long. The acting by DiCaprio and Pitt is great, as is the general large ensemble featuring lots of familiar faces from Tarantino’s catalogue. I do think the inclusion of Sharon Tate serves more of a symbolic purpose than a narrative purpose and wish the movie had given her more to do or even illuminated her more as a character. However, the buddy film we get between DiCaprio and Pitt is plenty entertaining. It might not be as narratively ambitious or intricate or even as satisfying as Tarantino’s other works, but Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is a fable for a Hollywood that may have only existed in Tarantino’s mind, but he’s recreated it with uncompromising affection.

Nate’s Grade: B+

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018)

Netflix might just be the best pasture yet for brothers Joel and Ethan Coen. The Oscar-winning filmmakers were reportedly creating a Western series for the online streaming giant but that has turned into an anthology film, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. The Coens’ love of the beautiful, the bizarre, the bucolic and the brazen are on full display with their six-part anthology movie that serves as reminder of what wonderfully unique cinematic voices they are. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is uneven, as most anthology films tend to by design, but it reaches that vintage Coen sweet spot of absurdity and profundity.

Netflix might just be the best pasture yet for brothers Joel and Ethan Coen. The Oscar-winning filmmakers were reportedly creating a Western series for the online streaming giant but that has turned into an anthology film, The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. The Coens’ love of the beautiful, the bizarre, the bucolic and the brazen are on full display with their six-part anthology movie that serves as reminder of what wonderfully unique cinematic voices they are. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is uneven, as most anthology films tend to by design, but it reaches that vintage Coen sweet spot of absurdity and profundity.

The best segment is also the one that kicks things off, the titular adventures of Buster Scruggs, a singing Gene Autry-style cowboy who manages to get into all sorts of scrapes. The tonal balancing act on this one is pure Coen, at once inviting an audience to nostalgically recall the Westerns of old while kicking you in the teeth with dark, hilariously violent turns that veer into inspired slapstick. There is a delightful absurdity to the segment thanks to the cheerful sociopath nature of Buster Scruggs, the fastest gun in the West that’s eager to show off at a moment’s notice. He’s a typical Coen creation, a wicked wordsmith finding himself into heaps of trouble, but through his quick wits and sudden bursts of violence, he’s able to rouse an entire saloon full of witnesses to his murder into a swinging, carousing group following him in song. I laughed long and hard throughout much of this segment. I was hooked and wanted to see where it would go next and how depraved it might get. Tim Blake Nelson (O Bother Where Art Thou) is wonderful as Buster Scruggs and perfectly finds the exact wavelength needed for the Coen’s brand of funny and peculiar. He’s like a combo Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny breaking the fourth wall to let the audience in on his merry bravado. The segment ends in a fitting fashion, another song that manages to be hilarious and strangely poignant at the same time. The Coens allow the scene to linger into a full-on duet of metaphysical proportions. I could have watched an entire series following Buster Scruggs but it may have been wise to cut things short and not to overstay its novelty.

The other best segments take very different tonal destinations. “All Gold Canyon” is a slower and more leisurely segment, following Tom Waits as a prospector who systematically works the land in search of a hidden trove of gold he nicknames “Mr. Pocket.” The step-by-step process has a lyrical nature to it, and it reminded me of the opening of There Will Be Blood where we follow Daniel Plainview’s initial success at unearthing the beginning of his fortune. Waits is fantastic and truly deserving of Oscar consideration as the prospector. He’s hardscrabble and resilient, and there’s a late moment where he’s narrating a near escape from death where he’s tearfully thankful, possibly losing himself in the moment, and so grateful that it made me tear up myself. The segment ebbs and flows on the strength of the visual storytelling and Waits. It’s a lovely short with a few hidden punches, which is also another fine way to describe the other best segment, “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” It stars Zoe Kazan (The Big Sick) as a woman making her way to Oregon with a wagon train. She’s heading west for a new life, one she was not prepared for and only doing so at the urging of her pushy brother who dies shortly into the journey. Now she’s on her own and struggling to find her own place in the larger world. There’s a very sweet and hopeful romance between her and Billy Knapp (Bill Heck), one of the wagon train leaders who is thinking of settling down. It’s also a segment that slows down, accounting for the longest running time of the six. It goes to great care to establish the rhythms of life on the road, where many people walked the thousands of miles across the plains. The budding courtship is at a realistic simmer, something with more promise than heat. It’s such an involving story that its downturn of an ending almost feels criminal, albeit even if the tragic setups were well placed. Both of these segments take a break from the signature irony of the Coens and sincerely round out their characters and personal journeys and the dangers that await them.

The other best segments take very different tonal destinations. “All Gold Canyon” is a slower and more leisurely segment, following Tom Waits as a prospector who systematically works the land in search of a hidden trove of gold he nicknames “Mr. Pocket.” The step-by-step process has a lyrical nature to it, and it reminded me of the opening of There Will Be Blood where we follow Daniel Plainview’s initial success at unearthing the beginning of his fortune. Waits is fantastic and truly deserving of Oscar consideration as the prospector. He’s hardscrabble and resilient, and there’s a late moment where he’s narrating a near escape from death where he’s tearfully thankful, possibly losing himself in the moment, and so grateful that it made me tear up myself. The segment ebbs and flows on the strength of the visual storytelling and Waits. It’s a lovely short with a few hidden punches, which is also another fine way to describe the other best segment, “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” It stars Zoe Kazan (The Big Sick) as a woman making her way to Oregon with a wagon train. She’s heading west for a new life, one she was not prepared for and only doing so at the urging of her pushy brother who dies shortly into the journey. Now she’s on her own and struggling to find her own place in the larger world. There’s a very sweet and hopeful romance between her and Billy Knapp (Bill Heck), one of the wagon train leaders who is thinking of settling down. It’s also a segment that slows down, accounting for the longest running time of the six. It goes to great care to establish the rhythms of life on the road, where many people walked the thousands of miles across the plains. The budding courtship is at a realistic simmer, something with more promise than heat. It’s such an involving story that its downturn of an ending almost feels criminal, albeit even if the tragic setups were well placed. Both of these segments take a break from the signature irony of the Coens and sincerely round out their characters and personal journeys and the dangers that await them.

The remaining three segments aren’t bad by any stretch (I’d rate each from fine to mostly good) but they don’t get close to the entertainment and artistic majesty of the others. The second segment, “Near Algodones,” has some fun moments as James Franco is an inept bank robber who seems to go from bad situation to new bad situation, getting out through miraculous means until his luck runs out. The interaction with a kooky Stephen Root is a highlight but the segment feels more like a series of ideas than any sort of story. Even for an anthology movie, the segment feels too episodic for its own good. The third segment, “Meal Ticket,” is about a traveling sideshow in small dusty towns in the middle of winter. Liam Neeson plays the owner and the main act is a thespian (Henry Melling, best known as Dudley Dursely in the Harry Potter films) with no arms and no legs. The thespian character says nothing else but his prepared oratory. It makes him a bit harder to try and understand internally. I was also confused by their relationship. Are they father/son? Business partners? It’s also the most repetitious short, by nature, with the monologues and stops bleeding into one another, giving the impression of the thankless and hard life of a performer trying to eek out a living. It’s a bit too oblique. The final segment, “The Mortal Remains,” is like an Agatha Christie chamber play. We listen to five characters engage in a philosophical and contentious debate inside a speeding stagecoach that will not slow down. It’s an actors showcase with very specifically written characters, the Coens sharp ear for local color coming through. The conversation takes on a symbolism of passing over to judgment in the afterlife, or maybe it doesn’t and I’m trying to read more into things. You may start to tune out the incessant chatter as I did. It’s a perfunctory finish for the movie.

The remaining three segments aren’t bad by any stretch (I’d rate each from fine to mostly good) but they don’t get close to the entertainment and artistic majesty of the others. The second segment, “Near Algodones,” has some fun moments as James Franco is an inept bank robber who seems to go from bad situation to new bad situation, getting out through miraculous means until his luck runs out. The interaction with a kooky Stephen Root is a highlight but the segment feels more like a series of ideas than any sort of story. Even for an anthology movie, the segment feels too episodic for its own good. The third segment, “Meal Ticket,” is about a traveling sideshow in small dusty towns in the middle of winter. Liam Neeson plays the owner and the main act is a thespian (Henry Melling, best known as Dudley Dursely in the Harry Potter films) with no arms and no legs. The thespian character says nothing else but his prepared oratory. It makes him a bit harder to try and understand internally. I was also confused by their relationship. Are they father/son? Business partners? It’s also the most repetitious short, by nature, with the monologues and stops bleeding into one another, giving the impression of the thankless and hard life of a performer trying to eek out a living. It’s a bit too oblique. The final segment, “The Mortal Remains,” is like an Agatha Christie chamber play. We listen to five characters engage in a philosophical and contentious debate inside a speeding stagecoach that will not slow down. It’s an actors showcase with very specifically written characters, the Coens sharp ear for local color coming through. The conversation takes on a symbolism of passing over to judgment in the afterlife, or maybe it doesn’t and I’m trying to read more into things. You may start to tune out the incessant chatter as I did. It’s a perfunctory finish for the movie.

Being a Coen brothers’ film, the technical merits are mesmerizing. The cinematography by Bruno Delbonnel (Amelie, Inside Llewyn Davis) is sumptuous and often stunning. The use of light and color is a gorgeous tapestry, and some of the visual arrangements could be copied into ready-made scenic postcards, in particular “Meal Ticket” and “All Gold Canyon.” The isolation, hostility, warmth, majesty of the setting is expertly communicated to the viewer. The production design and costuming are consummate as well. The musical score by longtime collaborator Carter Burwell is classic in its use of melancholy strings and motifs. It’s a glorious looking movie made with master craft care.

Being a Coen brothers’ film, the technical merits are mesmerizing. The cinematography by Bruno Delbonnel (Amelie, Inside Llewyn Davis) is sumptuous and often stunning. The use of light and color is a gorgeous tapestry, and some of the visual arrangements could be copied into ready-made scenic postcards, in particular “Meal Ticket” and “All Gold Canyon.” The isolation, hostility, warmth, majesty of the setting is expertly communicated to the viewer. The production design and costuming are consummate as well. The musical score by longtime collaborator Carter Burwell is classic in its use of melancholy strings and motifs. It’s a glorious looking movie made with master craft care.

Before its release, the Coens had talked about how hard it was to make their kind of movies within the traditional studio system, even with their 30 years of hits and classics. Netflix is desperately hungry for prestige content, so it looks like a suitable match. I’d happily welcome more Coen brothers’ movies like The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a goofy Western that’s equally heart wrenching as it is heart-warming, neither shying away from the cruelty and indifference of the harsh setting nor neglecting to take in its splendor. Just give them whatever money they need Netflix to keep these sort of movies a comin’.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Hostiles (2017)

A slow-paced Western with A-list actors, Scott Cooper’s Hostiles is a ponderous Western that feels too lost in its own expansive landscapes. It’s about an Army captain (Christian Bale) reluctantly taking the lead to escort a Cheyenne chief to die on his native soil. As you could expect from that premise, Hostiles is reverent and meditative to the point of boredom. It deals with Major Themes about man’s place in the world, connection to nature and the land, and our treatment of Native Americans, but it feels like it believe it’s saying a lot more than it accomplishes. The final film is over two hours but I kept waiting for the movie to feel more substantial, for the real story to start. The premise is workable and there are some interesting side characters, notably Rosamund Pike as the sole survivor of her family’s Native American attack, but it all feels underdeveloped to serve the central figure. It’s a story of one man having to come to terms and forgive himself for the cruel things he’s done in the past in the name of glory, honor, and patriotism. There are too many moments where characters reach out to remind him that he is, in fact, a Good Man. It gets to be too much. The talented supporting cast is generally wasted. Bale (The Big Short) is very internal, almost far too insular as a man speaking with looks and eyebrow arches, as he feels the weight of his soul over the course of this journey. I just grew restless with the movie and kept waiting for it to change gears or get better. Hostiles is not a poorly made movie, nor without some artistic merit, but it’s too languid and lacking.

A slow-paced Western with A-list actors, Scott Cooper’s Hostiles is a ponderous Western that feels too lost in its own expansive landscapes. It’s about an Army captain (Christian Bale) reluctantly taking the lead to escort a Cheyenne chief to die on his native soil. As you could expect from that premise, Hostiles is reverent and meditative to the point of boredom. It deals with Major Themes about man’s place in the world, connection to nature and the land, and our treatment of Native Americans, but it feels like it believe it’s saying a lot more than it accomplishes. The final film is over two hours but I kept waiting for the movie to feel more substantial, for the real story to start. The premise is workable and there are some interesting side characters, notably Rosamund Pike as the sole survivor of her family’s Native American attack, but it all feels underdeveloped to serve the central figure. It’s a story of one man having to come to terms and forgive himself for the cruel things he’s done in the past in the name of glory, honor, and patriotism. There are too many moments where characters reach out to remind him that he is, in fact, a Good Man. It gets to be too much. The talented supporting cast is generally wasted. Bale (The Big Short) is very internal, almost far too insular as a man speaking with looks and eyebrow arches, as he feels the weight of his soul over the course of this journey. I just grew restless with the movie and kept waiting for it to change gears or get better. Hostiles is not a poorly made movie, nor without some artistic merit, but it’s too languid and lacking.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Logan (2017)

The Wolverine solo films have not been good movies. The 2008 first film was widely lambasted and while it made its money it was an obvious artistic misfire. The second film, The Wolverine, directed by James Mangold was an improvement even though it had its silly moments and fell apart with a contrived final confrontation. The Wolverine movies were definitely the lesser, unworthy sidekick to the X-Men franchise, and this was a franchise that recently suffered from the near abysmal Apocalypse. Mangold returns for another Wolverine sequel but I was cautious. And then the cheerfully profane Deadpool broke box-office records and gave the Fox execs the latitude needed for a darker, bloodier, and more adult movie that’s more interested in character regrets than toy tie-ins. Thank goodness for the success of Deadpool because Logan is the X-Men movie, and in particular the Wolverine movie, I’ve been waiting for since the mutants burst onto the big screen some seventeen years ago. It is everything you could want in a Wolverine movie.

The Wolverine solo films have not been good movies. The 2008 first film was widely lambasted and while it made its money it was an obvious artistic misfire. The second film, The Wolverine, directed by James Mangold was an improvement even though it had its silly moments and fell apart with a contrived final confrontation. The Wolverine movies were definitely the lesser, unworthy sidekick to the X-Men franchise, and this was a franchise that recently suffered from the near abysmal Apocalypse. Mangold returns for another Wolverine sequel but I was cautious. And then the cheerfully profane Deadpool broke box-office records and gave the Fox execs the latitude needed for a darker, bloodier, and more adult movie that’s more interested in character regrets than toy tie-ins. Thank goodness for the success of Deadpool because Logan is the X-Men movie, and in particular the Wolverine movie, I’ve been waiting for since the mutants burst onto the big screen some seventeen years ago. It is everything you could want in a Wolverine movie.