Monthly Archives: February 2009

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Nothing comes easy when dealing with acclaimed screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. The most exciting scribe in Hollywood does not tend to water down his stories. Kaufman’s latest head-trip, Synecdoche, New York, is a polarizing work that follows a nontraditional narrative and works on a secondary existential level. That’s enough for several critics to hurtle words like “incomprehensible” and “confusing” as weapons intended to marginalize Synecdoche, New York as self-indulgent prattle. I guess no one wants to go to the movies and think any more. Thinking causes headaches, after all.

Nothing comes easy when dealing with acclaimed screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. The most exciting scribe in Hollywood does not tend to water down his stories. Kaufman’s latest head-trip, Synecdoche, New York, is a polarizing work that follows a nontraditional narrative and works on a secondary existential level. That’s enough for several critics to hurtle words like “incomprehensible” and “confusing” as weapons intended to marginalize Synecdoche, New York as self-indulgent prattle. I guess no one wants to go to the movies and think any more. Thinking causes headaches, after all.

Caden (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) is a struggling 40-year-old theater director trying to find meaning in his beleaguered life. His wife (Catherine Keener) has run off to Germany with his little daughter, Olive. He also manages to botch a potential romance with Hazel (Samantha Morton), a woman who works in the theater box-office who has an unusual crush on Caden. He’s also plagued by numerous mysterious health ailments that only seem to multiply. While his life seems to be in the pits, Caden is offered a theater grant of limitless money. He has big ambitions: he will restage every moment of his whole life to try and discover the hard truths about life and death. Caden must then cast actors to portray the various people in his life. Sammy (Tom Noonan) argues that no other actor could get closer to the truth of Caden; Sammy has been following and studying Caden for over 20 years (don’t bother asking why in a movie like this). Caden also casts his new wife, Claire (Michelle Williams), as herself. The theater production gets more and more complex, eventually requiring the “Caden” character to hire his own Caden actor. Caden hires Hazel to be his assistant and Sammy falls in love with her. Caden admonishes his actor, “That Hazel isn’t for you.” Caden then tries sleeping with “Hazel” (Emily Watson) to get even with the real Hazel. By producing a theatrical mechanism that almost seems self-sustaining, Caden wants to leave his mark on the world and potentially live forever.

I heard plenty of blather about how mind-numbing Synecdoche, New York was and how Kaufman had really done it this time when he composed a script that involves characters playing characters playing characters. People told me that it was all too much to keep track of and that it made their brains hurt. The movie is complex, yes, and demands a viewer to be actively engaged, but the movie is far from confusing and any person or critic that just throws up their hands and says, “Nope, too much to think about,” is doing their brain a disservice. The movie is relatively easy to follow in a simple linear cause-effect manner; Kaufman only really goes as deep as two iterations from reality, meaning that Caden has his initial doppelganger and then eventually that doppelganger must get his own Caden doppelganger (it’s not nearly as confusing as it sounds if you see it). Now, where the movie might be tricky to understand is how deeply contemplative and metaphorical it can manage to be, especially at its somber close. That doesn’t mean that Synecdoche, New York is impossible to understand only that it requires some extra effort to appreciate. But this movie pays off in huge ways on repeat viewings, adding texture to Kaufman’s intricately plotted big picture, unfolding into a richer statement about the nature of life and death and love.

I heard plenty of blather about how mind-numbing Synecdoche, New York was and how Kaufman had really done it this time when he composed a script that involves characters playing characters playing characters. People told me that it was all too much to keep track of and that it made their brains hurt. The movie is complex, yes, and demands a viewer to be actively engaged, but the movie is far from confusing and any person or critic that just throws up their hands and says, “Nope, too much to think about,” is doing their brain a disservice. The movie is relatively easy to follow in a simple linear cause-effect manner; Kaufman only really goes as deep as two iterations from reality, meaning that Caden has his initial doppelganger and then eventually that doppelganger must get his own Caden doppelganger (it’s not nearly as confusing as it sounds if you see it). Now, where the movie might be tricky to understand is how deeply contemplative and metaphorical it can manage to be, especially at its somber close. That doesn’t mean that Synecdoche, New York is impossible to understand only that it requires some extra effort to appreciate. But this movie pays off in huge ways on repeat viewings, adding texture to Kaufman’s intricately plotted big picture, unfolding into a richer statement about the nature of life and death and love.

Theater has often been an easy metaphor for life. William Shakespeare said, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.” Kaufman movies always dwell substantially with the nature of identity, and Synecdoche, New York views identity through the artifice of theater. Caden searches for something brutal and true via the stage, but of course eventually his search for truth becomes compromised with personal interests. Characters in Caden’s life are altered and in the end when Caden steps down, as himself, reality starts getting revised. The truth is often blurred through the process of interpretation. Caden ends up swapping identities with a bit player in the story of his life, potentially finding a greater sense of personal comfort as someone else. Don’t we all play characters in our lives? Don’t we all assume different identities for different purposes? Do we act differently at a job than at home, at church than at a bar? Caden remarks that there are no extras in life and that everyone is a lead in his or her own story.

Kaufman’s movie is also funny, like really darkly funny and borderline absurdist to the point of being some strange lost work by Franz Kafka (Hazel even mentions she’s reading Kafka’s The Trial). You may be so caught up trying to render the complexities of the story to catch all of the humor. The movie exists in a surreal landscape, where the characters treat the fantastic practically as mundane. Hazel’s house is constantly on fire and yet none of the characters regard this as dangerous or out of the ordinary. It is just another factor of life. The entire subplot with Hope Davis as a hilariously incompetent therapist is deeply weird. Caden suffers some especially cruel Job-like exploits, particularly what befalls his estranged daughter, Olive. He’s obsessed with her hidden whereabouts and European upbringing, to the point that Caden cannot even remember the name of his other daughter he has with Claire. There is a deathbed scene between the two that is equally sad and twisted given the astounding behavior that Caden is forced to apologize for. There are running gags that eventually transform into metaphors, like Caden’s many different medical ailments and the unhelpful bureaucratic doctors who know nothing and refuse to divulge any info. Kaufman even has Emily Watson, an actress mistaken for Morton, play the character of “Hazel.”

Kaufman’s movie is also funny, like really darkly funny and borderline absurdist to the point of being some strange lost work by Franz Kafka (Hazel even mentions she’s reading Kafka’s The Trial). You may be so caught up trying to render the complexities of the story to catch all of the humor. The movie exists in a surreal landscape, where the characters treat the fantastic practically as mundane. Hazel’s house is constantly on fire and yet none of the characters regard this as dangerous or out of the ordinary. It is just another factor of life. The entire subplot with Hope Davis as a hilariously incompetent therapist is deeply weird. Caden suffers some especially cruel Job-like exploits, particularly what befalls his estranged daughter, Olive. He’s obsessed with her hidden whereabouts and European upbringing, to the point that Caden cannot even remember the name of his other daughter he has with Claire. There is a deathbed scene between the two that is equally sad and twisted given the astounding behavior that Caden is forced to apologize for. There are running gags that eventually transform into metaphors, like Caden’s many different medical ailments and the unhelpful bureaucratic doctors who know nothing and refuse to divulge any info. Kaufman even has Emily Watson, an actress mistaken for Morton, play the character of “Hazel.”

This is Kaufman’s debut as a director and I think the movie ultimately benefits by giving its writer more control over the finished product. The movie is such a singular work of creativity that it helps by not having another director; there is no other artistic vision but Kaufman’s. While the film can feel slightly hermetic at times visually, Kaufman and cinematographer Frederick Elmes (The Ice Storm) pack the film with detail. Stylistically, the film is mannered but this is to make maximum impact for the vast amount of visual metaphors. Synecdoche, New York never feels as mannered as the recent Wes Anderson films, henpecked by a style that serves decoration rather than storytelling. The production design for the world-within-a-world is also alluring and imaginative, like a living, breathing dollhouse.

The assorted actors do well with their quirky, flawed characters, but clearly Hoffman is the linchpin to the film. He plays a character from middle age to old age, and at every step Hoffman manages to infuse some level of empathy for a man routinely disappointed by his own life. The failed yet lingering and hopeful romance between Caden and Hazel provides an almost sweet undercurrent for a character obsessed with death. Hoffman is convincing at every moment, even as a hobbled 80-year-old man, and gives a performance steeped in sadness but with the occasional glimmer of hope, whether it be the ambition of his theater project or the dream of holding Hazel once more. Morton is also wonderfully kindhearted and endearing as the woman that just seems to keep slipping away from Caden.

The assorted actors do well with their quirky, flawed characters, but clearly Hoffman is the linchpin to the film. He plays a character from middle age to old age, and at every step Hoffman manages to infuse some level of empathy for a man routinely disappointed by his own life. The failed yet lingering and hopeful romance between Caden and Hazel provides an almost sweet undercurrent for a character obsessed with death. Hoffman is convincing at every moment, even as a hobbled 80-year-old man, and gives a performance steeped in sadness but with the occasional glimmer of hope, whether it be the ambition of his theater project or the dream of holding Hazel once more. Morton is also wonderfully kindhearted and endearing as the woman that just seems to keep slipping away from Caden.

There’s no other way to say it but Synecdoche, New York is a movie that you need to see multiple times to appreciate. The plot is so grandiose in scope and ambition that one sitting does not do it justice. Kaufman has forged a strikingly peculiar movie that manages to be surreal and bleakly comic while also being poignant and humane. This is a big movie with big statements that can be easily missed, but for those willing to dig into the wealth of metaphor and reflection, Synecdoche, New York is a rewarding film experience that sticks with you. By the end of this movie, Kaufman has earned the merging of metaphor and narrative. I have already seen the movie twice and still cannot get it out of my thoughts. This isn’t the kind of movie that you feel warm affection for, like Kaufman’s blissfully profound Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. This movie is less a confounding puzzle than an intellectually stimulating examination on art, the human experience, and, ultimately death. If people would rather kill brain cells watching whatever dreck Hollywood secretes every week (cough, Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun-Li, cough) then that’s their prerogative. Give me a Charlie Kaufman movie and a bottle of aspirin any day.

Nate’s Grade: A

RocknRolla (2008)

I’m a fan of Guy Ritchie’s convoluted cockney comedic crime capers (wow, check out that alliteration), but this movie is just plodding and dull. The trouble is that Ritchie works best when he has one foot in the fantastic, with comically over-the-top and menacing underworld personalities. A Ritchie movie usually involves a lot of crisscrossing characters, but this is his first film where I couldn’t keep the folks straight, I couldn’t understand much of the personal connections, I couldn’t understand the purpose of the various characters and their various interplay, and frankly, I never bothered to care. RocknRolla has maybe two colorful characters (all hail Tom Wilkinson as a sleazy real estate gangster), but the rest of the movie is overstuffed with bland and forgettable toughs. What the hell are Ludacris and Jeremy Piven doing here? You could eliminate half of the cast and the movie would barely be affected. This movie is just way too straight and square for its own good. Ritchie is still a top-notch visual stylist, and the movie has a terrific deep focus digital video cinematography, but there are very few moments or visual flourishes in this flick that prove to be remotely memorable. I hope Ritchie does not make good on his promise to continue telling more stories with these characters and in this style because this many needs to get back to what he does so well, and that is telling the darkly comic escapades of larger than life Dick Tracy-esque villains and scoundrels.

I’m a fan of Guy Ritchie’s convoluted cockney comedic crime capers (wow, check out that alliteration), but this movie is just plodding and dull. The trouble is that Ritchie works best when he has one foot in the fantastic, with comically over-the-top and menacing underworld personalities. A Ritchie movie usually involves a lot of crisscrossing characters, but this is his first film where I couldn’t keep the folks straight, I couldn’t understand much of the personal connections, I couldn’t understand the purpose of the various characters and their various interplay, and frankly, I never bothered to care. RocknRolla has maybe two colorful characters (all hail Tom Wilkinson as a sleazy real estate gangster), but the rest of the movie is overstuffed with bland and forgettable toughs. What the hell are Ludacris and Jeremy Piven doing here? You could eliminate half of the cast and the movie would barely be affected. This movie is just way too straight and square for its own good. Ritchie is still a top-notch visual stylist, and the movie has a terrific deep focus digital video cinematography, but there are very few moments or visual flourishes in this flick that prove to be remotely memorable. I hope Ritchie does not make good on his promise to continue telling more stories with these characters and in this style because this many needs to get back to what he does so well, and that is telling the darkly comic escapades of larger than life Dick Tracy-esque villains and scoundrels.

Nate’s Grade: C

Confessions of a Shopaholic (2009)

Releasing a romantic comedy about a woman plagued by credit woes in the middle of a global financial meltdown? Doesn’t sound like the best example of escapist entertainment, but Confessions of a Shopaholic is infectious fun, and it’s all thanks to the delightfully funny lead performance by Isla Fisher. She seems like she stepped out of one of the old Hollywood screwball comedies from the 1930s. There’s a terrific hunger in her eyes and the woman knows how to punctuate a joke. The movie itself isn’t too shabby either. As far as formulaic romantic comedies go, this is one of the better ones in recent years. It has a little dash of everything, from slapstick to farcical thriller to romance to even some mildly potent drama. Director P.J. Hogan (Muriel’s Wedding) keeps the movie light and fun and even spruces up the flick with some interesting visuals, like animated CGI mannequins that come alive to tempt Fisher. Even though the movie holds onto a sitcom level plot for too long (mistaken identity), Confessions of a Shopaholic is a far worthier piece of entertainment than typically found in the rom-com genre, and Fisher is a comedian to rival the best.

Releasing a romantic comedy about a woman plagued by credit woes in the middle of a global financial meltdown? Doesn’t sound like the best example of escapist entertainment, but Confessions of a Shopaholic is infectious fun, and it’s all thanks to the delightfully funny lead performance by Isla Fisher. She seems like she stepped out of one of the old Hollywood screwball comedies from the 1930s. There’s a terrific hunger in her eyes and the woman knows how to punctuate a joke. The movie itself isn’t too shabby either. As far as formulaic romantic comedies go, this is one of the better ones in recent years. It has a little dash of everything, from slapstick to farcical thriller to romance to even some mildly potent drama. Director P.J. Hogan (Muriel’s Wedding) keeps the movie light and fun and even spruces up the flick with some interesting visuals, like animated CGI mannequins that come alive to tempt Fisher. Even though the movie holds onto a sitcom level plot for too long (mistaken identity), Confessions of a Shopaholic is a far worthier piece of entertainment than typically found in the rom-com genre, and Fisher is a comedian to rival the best.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Coraline (2009)

The beauty of stop-motion animation is that everything is painstakingly handcrafted so that it’s like watching a whole other world. Coraline is a wonder for the eyes and I loved just watching the movement of characters, their facial expressions, which were all done in great fluid motions. I loved that I could see Coraline thinking just through how her eyes were animated. The story, based upon the Neil Gaiman book, is about an alternative world where people have buttons for eyes provides enough eerie intrigue and some creepy imagery to spook younger kids. This is a fantasy film that doesn’t shy away from childhood scares. Coraline has an altogether pleasant feel with its spunky heroine and fine vocal cast (Dakota Fanning did not get on my nerves at all), but what’s most special is just watching the movie come alive; it’s enchanting to watch this world simply exist. There are some terrific displays of imagination in the alternative world, and it all looks even snazzier in 3-D where the world takes on further depth. Director Henry Selick (Nightmare Before Christmas) is the master of this peculiar art and thankfully Coraline follows its own visual style, never stooping to imitating Nightmare (like Corpse Bride). This is a visually stunning movie that may not leave much of an impression once it’s over (predictable story, thin plot, kind of slow ending). Coraline is a feast of artistic talent with something to discover in every awesome second.

The beauty of stop-motion animation is that everything is painstakingly handcrafted so that it’s like watching a whole other world. Coraline is a wonder for the eyes and I loved just watching the movement of characters, their facial expressions, which were all done in great fluid motions. I loved that I could see Coraline thinking just through how her eyes were animated. The story, based upon the Neil Gaiman book, is about an alternative world where people have buttons for eyes provides enough eerie intrigue and some creepy imagery to spook younger kids. This is a fantasy film that doesn’t shy away from childhood scares. Coraline has an altogether pleasant feel with its spunky heroine and fine vocal cast (Dakota Fanning did not get on my nerves at all), but what’s most special is just watching the movie come alive; it’s enchanting to watch this world simply exist. There are some terrific displays of imagination in the alternative world, and it all looks even snazzier in 3-D where the world takes on further depth. Director Henry Selick (Nightmare Before Christmas) is the master of this peculiar art and thankfully Coraline follows its own visual style, never stooping to imitating Nightmare (like Corpse Bride). This is a visually stunning movie that may not leave much of an impression once it’s over (predictable story, thin plot, kind of slow ending). Coraline is a feast of artistic talent with something to discover in every awesome second.

Nate’s Grade: A-

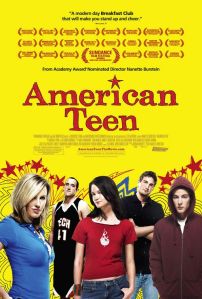

American Teen (2008)

Filmmaker Nanette Burstein (On the Ropes) wanted to document the lives of actual American teenagers. After a national search, she settled on the town of Warsaw, Indiana, which we’re told in the opening narration is “mostly white, mostly Christian, and red state all the way.” American Teen is the feature-length documentary that chronicles the lives of four Warsaw teens during their senior year. The class of 2006 includes Colin, a basketball star worried about securing a scholarship. His father, an Elvis impersonator, supports his son but reminds the kid that dad has no money for school, so it’s either a scholarship or the Army. This, naturally, places tremendous pressure on a 17-year-old and his play diminishes as he tries to up his stats. There’s Megan, the queen bee at the school who feels pressured by her family to get into Notre Dame. This makes her act like a cretin, apparently. Jake is a kid who feels uncomfortable in his own acne-scarred skin. He plays video games a lot and desperately wants to find a girlfriend. Then there’s Hannah, the artsy girl prone to spontaneous dancing who feels trapped by her town.

Filmmaker Nanette Burstein (On the Ropes) wanted to document the lives of actual American teenagers. After a national search, she settled on the town of Warsaw, Indiana, which we’re told in the opening narration is “mostly white, mostly Christian, and red state all the way.” American Teen is the feature-length documentary that chronicles the lives of four Warsaw teens during their senior year. The class of 2006 includes Colin, a basketball star worried about securing a scholarship. His father, an Elvis impersonator, supports his son but reminds the kid that dad has no money for school, so it’s either a scholarship or the Army. This, naturally, places tremendous pressure on a 17-year-old and his play diminishes as he tries to up his stats. There’s Megan, the queen bee at the school who feels pressured by her family to get into Notre Dame. This makes her act like a cretin, apparently. Jake is a kid who feels uncomfortable in his own acne-scarred skin. He plays video games a lot and desperately wants to find a girlfriend. Then there’s Hannah, the artsy girl prone to spontaneous dancing who feels trapped by her town.

I found American Teen to be largely unbelievable for two major reasons. First, teenagers today are way too media savvy after having grown up on a bevy of reality TV programming, the ultimate genre of manipulation. Remember way back in 1991 when MTV first started The Real World, the pioneering reality TV show? The people selected to live together as a social experiment were interesting, unguarded, a nice cross-section of the country; you felt like you could run into these people on the street some time. Then about half way into its run, the likely turning point being the Las Vegas season, The Real World participants became self-aware. They knew to exaggerate behavior for manufactured drama, to play up romantic crushes, and to work from the realm of playing a well-defined cliché character; no longer did these people feel real, instead they felt like drunken auditions for a really lousy soap opera. And all of the people started looking inordinately beautiful, chiseled hunks and leggy, waif-thin models. When was the last time they ever had an overweight person on that show? Anyway, the point of this anecdote is that thanks to the machinations of reality TV, teenagers today have grown up with the concept of cameras and they know how to manipulate reality. One could argue that you will never capture the true essence of a person by pointing a camera at them, because the instant a camera is placed to document reality it changes reality; people talk differently, either more reserved or confessional. A camera changes reality, but this discussion point is a little beyond the realm of American Teen. So I doubt the legitimacy of watching the “real lives” of “real students,” especially when these kids come from a more affluent area and probably digest other MTV semi-reality dramas like the unquestionably fake The Hills.

So how would you behave if you knew a film crew was making a documentary in your school? I fully believe that many of the actions caught on camera are done so because the students wanted to ensure that they would be in a movie. I cannot blame them. I mean, if I was close to being involved in a film I would probably check every possibility to ensure my lovely presence eventually fills up the big screen. What do you want from kids who have grown up as a generation of self-reflective narcissists thanks to reality TV and uninvolved parents (sorry, soapbox moment)? This is why the nature of documenting reality in a high school setting is questionable. Burstein’s cameras follow Jake around and he’s able to walk up to girls and ask them out, point blank. Would he normally be so bold? I don’t know. What I know for certainty is that there would be fewer girls interested in the acne-scarred self-proclaimed geek if he didn’t have the adjoining camera crew. I’m sure girls looked at Jake and thought, “Here’s my ticket to being in a movie.” I’m not trying to be mean here because Jake is a rather nice, typically uncomfortable and socially awkward teenager who will find his niche once he leaves the confines of high school. I’ve known several Jakes in my life. But I don’t believe that a socially awkward kid like this naturally dates three different girls, all of them pretty, without the promised presence of cameras.

So how would you behave if you knew a film crew was making a documentary in your school? I fully believe that many of the actions caught on camera are done so because the students wanted to ensure that they would be in a movie. I cannot blame them. I mean, if I was close to being involved in a film I would probably check every possibility to ensure my lovely presence eventually fills up the big screen. What do you want from kids who have grown up as a generation of self-reflective narcissists thanks to reality TV and uninvolved parents (sorry, soapbox moment)? This is why the nature of documenting reality in a high school setting is questionable. Burstein’s cameras follow Jake around and he’s able to walk up to girls and ask them out, point blank. Would he normally be so bold? I don’t know. What I know for certainty is that there would be fewer girls interested in the acne-scarred self-proclaimed geek if he didn’t have the adjoining camera crew. I’m sure girls looked at Jake and thought, “Here’s my ticket to being in a movie.” I’m not trying to be mean here because Jake is a rather nice, typically uncomfortable and socially awkward teenager who will find his niche once he leaves the confines of high school. I’ve known several Jakes in my life. But I don’t believe that a socially awkward kid like this naturally dates three different girls, all of them pretty, without the promised presence of cameras.

Also, there’s this popular guy Mitch completely thrown in at the middle of the film. All of a sudden he sees Hannah onstage rocking out at a school battle of the bands function, and the movie slows down, Hannah literally starts glowing, and Mitch says, “Wow, I have a crush on Hannah Bailey.” Allow me to doubt the sincerity of this sudden cross-clique crush. We never witness the beginning of this relationship, each side feeling the other out, the nervousness and delightful possibilities. We just get a voice over of Mitch saying he likes her and then the film cuts to like weeks into their supposed relationship when they’re goofing off at a gas station. When Hannah is invited to a party with Mitch’s friends, naturally she’s going to feel a bit out of place amongst the cool, popular crowd. He hangs out with his friends instead of his girlfriend. He makes sure to say hey to everyone else even while Hannah is sitting next to him. The next day Mitch breaks up with Hannah via the modern marvel of text messaging (ouch). You never see Mitch again until the end credits reveal that he feels he has matured. Essentially, Mitch is only seen and introduced to the movie because of his attachment to Hannah. Clearly, Mitch knew that if he buddied up next to the pixie girl he would ensure some place in the movie’s running time. It worked, because Mitch is featured in the trailer, the poster, and even tagged along on the national press tour. To paraphrase the title of Burstein’s superior documentary, the kid found a way to stay in the picture.

My second point of contention is that Burstein has taken scissors to 1200+ hours of footage to make her documentary about high school stereotypes, not people. Burstein has selected five figures to spotlight and she has whittled them down to one-word stereotypes: jock (Colin), geek (Jake), princess (Megan), rebel (Hannah), and heartthrob (Mitch). She isn’t destroying these lazy classifications but reinforcing them willfully. The marketing campaign around American Teen recreated the poster from The Breakfast Club. I swear, I think that art imitated life and now high schoolers are just imitating what they have seen propagated time and again as stone-cold reality in their schools: the rigid social caste system. There are so many missed opportunities by painting in such broad strokes. Colin is a jock because he plays on the basketball squad, but why can’t he also be a geek? Why can’t a rebel be a princess? I feel tacky talking in such degrading, baby-fied terms. Burstein doesn’t help her case by giving the main figures their own animated fantasy segments. Hannah is obviously the star of the film, and Burstein has seen to it that she narrates the tale as well. I suspect some canniness on Burstein’s part. Either the filmmaker felt that Hannah would most reflect the spirits of the crowds that attend indie documentaries, thus ensuring a bigger gross, or Burstein saw much of herself in Hannah and naturally wanted to make the “different girl” the star, possibly working through some of her own high school demons.

My second point of contention is that Burstein has taken scissors to 1200+ hours of footage to make her documentary about high school stereotypes, not people. Burstein has selected five figures to spotlight and she has whittled them down to one-word stereotypes: jock (Colin), geek (Jake), princess (Megan), rebel (Hannah), and heartthrob (Mitch). She isn’t destroying these lazy classifications but reinforcing them willfully. The marketing campaign around American Teen recreated the poster from The Breakfast Club. I swear, I think that art imitated life and now high schoolers are just imitating what they have seen propagated time and again as stone-cold reality in their schools: the rigid social caste system. There are so many missed opportunities by painting in such broad strokes. Colin is a jock because he plays on the basketball squad, but why can’t he also be a geek? Why can’t a rebel be a princess? I feel tacky talking in such degrading, baby-fied terms. Burstein doesn’t help her case by giving the main figures their own animated fantasy segments. Hannah is obviously the star of the film, and Burstein has seen to it that she narrates the tale as well. I suspect some canniness on Burstein’s part. Either the filmmaker felt that Hannah would most reflect the spirits of the crowds that attend indie documentaries, thus ensuring a bigger gross, or Burstein saw much of herself in Hannah and naturally wanted to make the “different girl” the star, possibly working through some of her own high school demons.

There’s also the issue of how staged some of this comes across. Am I to believe that Burstein’s camera crew managed to capture those perfect moments where the students stare out into space, thoughtfully? Am I to believe that the camera crew managed to capture everyone’s dirty little text messages then and there in the moment? Am I to believe that scenes of Hannah dramatically walking down the hallway weren’t planned? I’m forgiving when it comes to re-enactments but when a movie feels overburdened with re-enactments or posed figures, then it feels too manufactured. Just like The Hills.

Perhaps I’m coming down too hard on American Teen. After all, most documentaries distort some facet of reality and generally are edited to present a series of points. But the reason American Teen doesn’t work is because it offers zero insights into the American high school setting and little to no insights with its “characters.” Hannah is a cute girl with an independent streak but I fail to get a sense of her as a person. She gets dumped twice over the course of American Teen, suffers from crippling anxiety to the point that she misses almost a month of class, and she longs to leave the reach of her conservative town for the holy destination of California, so why then does the film not present her as a person instead of a classification? I also get the feeling that we don’t see any of would-be filmmaker Hannah’s own work because Burstein may be shielding her subject from the harsh realities or critical response.

Obviously Megan is the villain of the piece and Burstein takes advantage of the girl’s self-absorbed sense of entitlement. Megan could be an interesting subject as far as casual cruelty. Megan vandalizes a student council member’s home because the guy had the gall to devise a different prom theme. We watch Megan literally spray paint a penis on a window followed by the word “FAG,” and then she whines that everyone is being mean to her even when the punishment she gets for a borderline hate crime is a slap on the wrists. Megan’s friend Erica makes the unfortunate decision to send a topless picture of herself in an e-mail to the guy she likes, who happens to be Megan’s friend and object of territory. So Megan briskly sends the picture to scads and scads of students with e-mail subject lines like “silver dollars” and “pepperonis.” Megan then leaves mean-spirited voice mail messages saying that Erica is destined “to live the rest of her life as a slut.” This is her friend! Burstein has the good sense of mind to interview a teary-eyed Erica after the topless photo fallout, and it probably is the emotional highpoint of the film because it’s so honest and wounded. Why not follow Erica after this? Surely her story, recovering from humiliation, is more intriguing then watching Megan scoot along her privileged life or whether or not Colin can be a better teammate. Speaking of the tall kid with the Jay Leno-sized chin, why does his dad insist that Colin needs a basketball scholarship or else “it’s the Army”? Has he not heard of student loans? Does Colin’s father believe sending his son into a war zone is preferable to amassing debt?

Obviously Megan is the villain of the piece and Burstein takes advantage of the girl’s self-absorbed sense of entitlement. Megan could be an interesting subject as far as casual cruelty. Megan vandalizes a student council member’s home because the guy had the gall to devise a different prom theme. We watch Megan literally spray paint a penis on a window followed by the word “FAG,” and then she whines that everyone is being mean to her even when the punishment she gets for a borderline hate crime is a slap on the wrists. Megan’s friend Erica makes the unfortunate decision to send a topless picture of herself in an e-mail to the guy she likes, who happens to be Megan’s friend and object of territory. So Megan briskly sends the picture to scads and scads of students with e-mail subject lines like “silver dollars” and “pepperonis.” Megan then leaves mean-spirited voice mail messages saying that Erica is destined “to live the rest of her life as a slut.” This is her friend! Burstein has the good sense of mind to interview a teary-eyed Erica after the topless photo fallout, and it probably is the emotional highpoint of the film because it’s so honest and wounded. Why not follow Erica after this? Surely her story, recovering from humiliation, is more intriguing then watching Megan scoot along her privileged life or whether or not Colin can be a better teammate. Speaking of the tall kid with the Jay Leno-sized chin, why does his dad insist that Colin needs a basketball scholarship or else “it’s the Army”? Has he not heard of student loans? Does Colin’s father believe sending his son into a war zone is preferable to amassing debt?

American Teen is a pseudo-documentary that has little intention to dig deeper under the surface of the realities of high school life. If your high school experience exactly mirrors this film, then perhaps you watched too many movies. Or the filmmakers did and tried to feed into the film idea of what goes on in a high school. Or both.

Nate’s Grade: C

You must be logged in to post a comment.