Blog Archives

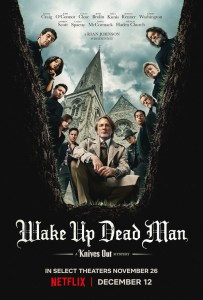

Wake Up Dead Man (2025)

Being the third in its franchise, we now have a familiar idea of what to expect from a Knives Out murder mystery. Writer/director Rian Johnson has a clear love for the whodunit mystery genre but he loves even more turning the genre on its head, finding something new in a staid and traditional style of storytelling. The original 2019 hit movie let us in on the “murderer” early, and it became more of a game of out-thinking the world-class detective, Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig). With the 2022 sequel Glass Onion, the first of Netflix’s two commissioned sequels for a whopping $400 million, Johnson reinvented the unexpected twin trope and let us investigate a den of tech bro vipers with added juicy dramatic irony. With his latest, Wake Up Dead Man, Johnson is trying something thematically different. Rather than adding a meta twist to ages-old detective tropes, Johnson is putting his film’s emphasis on building out the themes of faith. This is a movie more interested in the questions and value of faith in our modern world. It still has its canny charms and surprises, including some wonderfully daffy physical humor, but Wake Up Dead Man is the most serious and soul-searching of the trilogy thus far, and a movie that hit me where it counts.

Being the third in its franchise, we now have a familiar idea of what to expect from a Knives Out murder mystery. Writer/director Rian Johnson has a clear love for the whodunit mystery genre but he loves even more turning the genre on its head, finding something new in a staid and traditional style of storytelling. The original 2019 hit movie let us in on the “murderer” early, and it became more of a game of out-thinking the world-class detective, Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig). With the 2022 sequel Glass Onion, the first of Netflix’s two commissioned sequels for a whopping $400 million, Johnson reinvented the unexpected twin trope and let us investigate a den of tech bro vipers with added juicy dramatic irony. With his latest, Wake Up Dead Man, Johnson is trying something thematically different. Rather than adding a meta twist to ages-old detective tropes, Johnson is putting his film’s emphasis on building out the themes of faith. This is a movie more interested in the questions and value of faith in our modern world. It still has its canny charms and surprises, including some wonderfully daffy physical humor, but Wake Up Dead Man is the most serious and soul-searching of the trilogy thus far, and a movie that hit me where it counts.

In upstate New York, Pastor Jud (Josh O’Connor) has been assigned to a church to help the domineering Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin). The congregation is dwindling with the exception of a few diehards holding onto Wicks’ message of exclusion and division. The two pastors are ideologically in opposition, with Pastor Jud favoring a more nurturing and welcoming approach for the Christian church. Then after one fiery sermon, Wicks retires to an antechamber and winds up dead, with the primary suspect with the most motivation being Pastor Jud. Enter famous detective extraordinaire Benoit Blanc to solve the riddle.

I appreciated how the movie is also an examination on the different voices fighting for control of the direction of the larger Christian church. Wicks is your traditional fire-and-brimstone preacher, a man who sees the world as a nightmarish carnival of temptations waiting to drag down souls. He sees faith as a cudgel against the horrors of the world, and for him the church is about banding together and fighting against those outside forces no matter how few of you remain to uphold the crusade. Pastor Jud rejects this worldview, arguing that if you think of the church as a pugilist in a battle then you’ll start seeing enemies and fights to come to all places. He’s a man desperate to escape his violent past and to see the church as a resource of peace and resolution but Wicks lusts for the fight and the sense of superiority granted by his position. He relishes imposing his wrath onto others, and his small posse of his most true believers consider themselves hallowed because they’re on the inside of a special club. For Pastor Jud, he’s rejecting hatred in his heart and looks at the teachings of Jesus as an act of love and empathy. It’s not meant to draw lines and exclude but to make connections. These two philosophical differences are in direct conflict for the first half of the movie, one viewing the church as an open hand and the other as a fist. It’s not hard to see where Johnson casts his lot since Pastor Jud is our main character, after all. I also appreciated the satirical tweaks of the church’s connections to dubious conservative political dogma, like Wicks’ disciples trying to convince themselves the church needs a bully of its own to settle scores (“What is truth anyway?” one incredulously asks after some upsetting news about their patriarch). It’s not hard to make a small leap to the self-serving rationalizations of supporting a brazenly ungodly figure like Trump. At its core, this movie is about people wrestling with big ideas, and Johnson has the interest to provide space for these ideas and themes while also keeping his whodunit running along pace-for-pace.

I appreciated how the movie is also an examination on the different voices fighting for control of the direction of the larger Christian church. Wicks is your traditional fire-and-brimstone preacher, a man who sees the world as a nightmarish carnival of temptations waiting to drag down souls. He sees faith as a cudgel against the horrors of the world, and for him the church is about banding together and fighting against those outside forces no matter how few of you remain to uphold the crusade. Pastor Jud rejects this worldview, arguing that if you think of the church as a pugilist in a battle then you’ll start seeing enemies and fights to come to all places. He’s a man desperate to escape his violent past and to see the church as a resource of peace and resolution but Wicks lusts for the fight and the sense of superiority granted by his position. He relishes imposing his wrath onto others, and his small posse of his most true believers consider themselves hallowed because they’re on the inside of a special club. For Pastor Jud, he’s rejecting hatred in his heart and looks at the teachings of Jesus as an act of love and empathy. It’s not meant to draw lines and exclude but to make connections. These two philosophical differences are in direct conflict for the first half of the movie, one viewing the church as an open hand and the other as a fist. It’s not hard to see where Johnson casts his lot since Pastor Jud is our main character, after all. I also appreciated the satirical tweaks of the church’s connections to dubious conservative political dogma, like Wicks’ disciples trying to convince themselves the church needs a bully of its own to settle scores (“What is truth anyway?” one incredulously asks after some upsetting news about their patriarch). It’s not hard to make a small leap to the self-serving rationalizations of supporting a brazenly ungodly figure like Trump. At its core, this movie is about people wrestling with big ideas, and Johnson has the interest to provide space for these ideas and themes while also keeping his whodunit running along pace-for-pace.

There is a moment of clarification that is so sudden, so unexpectedly beautiful that it literally had me welling up in tears and dumbstruck at Johnson’s capabilities as a precise storyteller. It’s late into Act Two, and Blanc and Pastor Jud are in the thick of trying to gather all the evidence they can and chase down those leads to come to a conclusive answer as to how Pastor Jud is innocent. The scene begins with Pastor Jud talking on the phone trying to ascertain when a forklift order was placed. The woman on the other side of the line, Louise (Bridget Everett, Somebody Somewhere), is a chatty woman who is talking in circles rather than getting to the point, delaying the retrieval of desired information and causing nervous agitation for Pastor Jud. It’s a familiar comedy scenario of a person being denied what they want and getting frustrated from the oblivious individual causing that annoying delay. Then, all of a sudden, as the frustration is reaching a breaking point, she quietly asks if she can ask Pastor Jud a personal question. This takes him off guard but he accepts, and from there she becomes so much more of a real person, not just an annoyance over the phone. She mentions her parent has cancer and is in a bad way and she’s unsure how to repair their relationship while they still have such precious time left. The movie goes still and lingers, giving this woman and her heartfelt vulnerability the floor, and Pastor Jud reverts back to those instincts to serve. He goes into another room to provide her privacy and counsels her, leading her in a prayer.

The entire scene is magnificent and serves two purposes. This refocuses Pastor Jud on what is most important, not chasing this shaggy investigation with his new buddy Blanc but being a shepherd to others. It re-calibrates the character’s priorities and perspective. It also, subtlety, does the same for the audience. The wacky whodunit nature of the locked-door mystery is intended as the draw, the game of determining who and when are responsible for this latest murder. It’s the appeal of these kinds of movies, and yet, Johnson is also re-calibrating our priorities to better align with Pastor Jud. Because ultimately the circumstances of the case will be uncovered, as well as the who or whom’s responsible, and you’ll get your answers, but will they be just as important once you have them? Or will the themes under-girding this whole movie be the real takeaway, the real emotionally potent memory of the film? As a mystery, Wake Up Dead Man is probably dead-last, no pun intended, in the Knives Out franchise, but each movie is trying to do something radical. With this third film, it’s less focused on the twists and turns of its mystery and its secrets. It’s more focused on the challenging nature of faith as well as the empathetic power that it can afford others when they choose to be vulnerable and open.

The entire scene is magnificent and serves two purposes. This refocuses Pastor Jud on what is most important, not chasing this shaggy investigation with his new buddy Blanc but being a shepherd to others. It re-calibrates the character’s priorities and perspective. It also, subtlety, does the same for the audience. The wacky whodunit nature of the locked-door mystery is intended as the draw, the game of determining who and when are responsible for this latest murder. It’s the appeal of these kinds of movies, and yet, Johnson is also re-calibrating our priorities to better align with Pastor Jud. Because ultimately the circumstances of the case will be uncovered, as well as the who or whom’s responsible, and you’ll get your answers, but will they be just as important once you have them? Or will the themes under-girding this whole movie be the real takeaway, the real emotionally potent memory of the film? As a mystery, Wake Up Dead Man is probably dead-last, no pun intended, in the Knives Out franchise, but each movie is trying to do something radical. With this third film, it’s less focused on the twists and turns of its mystery and its secrets. It’s more focused on the challenging nature of faith as well as the empathetic power that it can afford others when they choose to be vulnerable and open.

Blanc doesn’t even show up for the first forty or so minutes, giving the narration duties to Pastor Jud setting the scene of his own. Craig (Queer) is a bit more subdued in this movie, both given the thematic nature of it as well as ceding the spotlight to his co-star. Blanc is meant to be the more stubborn realist of the picture, an atheist who views organized religion as exploitative claptrap (he seems the kind of guy who says “malarkey” regularly). His character’s journey isn’t about becoming a true believer by the end. It’s about recognizing and accepting how faith can affect others for good, specifically the need for redemption. Minor spoilers ahead. His final grand moment, the sermonizing we expect from our Great Detectives when they finally line up all the suspects and clues and knock them down in a rousing monologue, is cast aside, as Blanc recognizes his own ego could be willfully harmful and in direct opposition to Pastor Jud’s mission. It’s a performance that asks more of Craig than to mug for the camera and escape the molasses pit of his cartoonish Southern drawl. He’s still effortlessly enjoyable in the role, and may he continue this series forever, but Wake Up Dead Man proves he’s also just as enjoyable as the second banana in a story.

O’Connor (Challengers, The Crown) is our lead and what a terrific performance he delivers. The character is exactly who you would want a pastor to be: humble, empathetic, honest, and striving to do better. It’s perhaps a little too cute to call O’Connor’s performance “soulful” but I kept coming back to that word because this character is such a vital beating heart for others, so hopeful to make an impact. It’s wrapped up in his own hopes of turning his life around, turning his personal tragedy into meaning, devoting himself to others as a means of repentance. He’s a man in over his head but he’s also an easy underdog to root for, just like Ana de Armas’ character was in the original Knives Out. You want this man to persevere because he has a good moral center and because our world could use more characters like this. O’Connor has such a brimming sense of earnestness throughout that doesn’t grow maudlin thanks to Johnson’s deft touch and mature exploration of his themes. O’Connor is such a winning presence, and when he’s teamed with Blanc, the two form an enjoyable buddy comedy, each getting caught up in the other’s enthusiasm.

O’Connor (Challengers, The Crown) is our lead and what a terrific performance he delivers. The character is exactly who you would want a pastor to be: humble, empathetic, honest, and striving to do better. It’s perhaps a little too cute to call O’Connor’s performance “soulful” but I kept coming back to that word because this character is such a vital beating heart for others, so hopeful to make an impact. It’s wrapped up in his own hopes of turning his life around, turning his personal tragedy into meaning, devoting himself to others as a means of repentance. He’s a man in over his head but he’s also an easy underdog to root for, just like Ana de Armas’ character was in the original Knives Out. You want this man to persevere because he has a good moral center and because our world could use more characters like this. O’Connor has such a brimming sense of earnestness throughout that doesn’t grow maudlin thanks to Johnson’s deft touch and mature exploration of his themes. O’Connor is such a winning presence, and when he’s teamed with Blanc, the two form an enjoyable buddy comedy, each getting caught up in the other’s enthusiasm.

Johnson has assembled yet another all-star collection of actors eager to have fun in his genre retooling. Some of these roles are a little more thankless than others (Sorry Mila Kunis and Thomas Haden Church, but it was nice of you to come down and play dress-up with the rest of the cast). The clear standout is Glenn Close (Hillbilly Elegy) as Martha, the real glue behind Wicks’ church as well as an ardent supporter of his worldview of the damned and the righteous. She has a poignant character arc coming to terms with how poisonous that divisive, holier-than-thou perspective can be. Close is fantastic and really funny at certain parts, giving Martha an otherworldly presence as a woman always within earshot. Brolin (Weapons) is equally fun as the pugnacious Wicks, a man given to hypocrisy but also resentful of others who would reduce his position of influence. The issue with Wake Up Dead Man is that elevating Pastor Jud to co-star level only leaves so much room for others, and so the suspect list is under-served, arguably wasted, especially Andrew Scott (All of Us Strangers) as a red-pilled sci-fi writer looking for a comeback. The best of the bunch is Daryl McCormack (Good Luck to You, Leo Grande) as a conniving wannabe in Republican politics trying to position himself for a pricey media platform and Cailee Spaeny (Alien: Romulus) as a cellist who suffers from deliberating pain and was desperate for a miracle delivered by Wicks. He’s the least genuine person, she’s hoping for miraculous acts, and both will be disappointed from what they seek.

Wake Up Dead Man (no comma in that title, so no direct command intended) is an equally fun movie with silly jokes and a reverent exploration of the power of faith and its positive impact, not even from a formal religious standpoint but in the simple act of connecting to another human being in need. This is the richest thematically of the three Knives Out movies but it also might be the weakest of the mysteries. The particulars of the case just aren’t as clever or as engaging as the others, but then again not every Agatha Christie mystery novel could be an absolute all-time ripper. That’s why the movie’s subtle shifts toward its themes and character arcs as being more important is the right track, and it makes for a more emotionally resonant and reflective experience, one that has replay value even after you know the exact particulars of the case. If you’re a fan of the Knives Out series, there should be enough here to keep you enraptured for more. Because of that added thematic richness, Wake Up Dead Man has an argument as the best sequel (yet).

Nate’s Grade: A-

Weapons (2025)

Zack Cregger began his career as one of the co-creators and co-stars of the sketch comedy troupe, The Whitest Kids U Know. This led to a poorly received sex comedy, 2009’s Miss March, which Cregger co-directed and starred as the lead. Then in 2022, Cregger made a name for himself in a very different genre, writing and directing Barbarian, a movie whose identity kept shifting with twists and world-building buried underneath its simple Air B&B gone awry setup. From there, Cregger joined the ranks of Jordan Peele, John Krasinski, and other horror-thriller upstarts best known for comedy. It became a question over what Cregger would do next, which sparked a bidding war for Weapons. It’s easy to see why with such a terrific premise: one day a classroom of kids all run out into the night at the same time, all except for one child, and nobody knows why. Weapons confirms Cregger’s genre transformation and the excitement that deservingly follows each new release. Each new Cregger horror movie is a game of shifting expectations and puzzles, though the game itself might be the only point.

The premise is immediately grabbing and Cregger’s clever structural gambits add to that intrigue. Right away in the opening narration from an unseen child, we’re given the state of events in this small town, already reckoning with an unknowable tragedy. The screenplay takes a page from Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino, following different lead characters to learn about their personal perspectives. It continually allows the movie to re-frame itself, allowing us to pick up details or further context with each new person giving us a fuller sense of the big picture. Rather than resetting every twenty minutes or so, the movie offers an implicit promise of delivering something new at those junctures, usually leaving that previous lead character in some kind of dire cliffhanger. With each new portion, we can gain some further insight, but it also allows the story to ground its focus and try on different tones. With Justine (Julia Garner), we see a woman who is trying to figure out how to regain her life she feels has been unfairly stripped away, and many of her coping mechanisms are self-destructive old habits. With Archer (Josh Brolin), we see a father consumed by his sudden loss and the reflection it forces him into, while also obsessing over what possible investigative details he can put together to possibly provide a framework of an answer. Then with other characters, which I won’t spoil, we gain other perspectives less directly involved that approach a dark comedy of errors. At one point, you may even wonder when the movie is going to remember those missing kids again. I appreciated that Cregger resolves his mystery with enough time to really examine its implications. This isn’t just a last-minute twist or Scream-like unveiling of the villain coming to light. I also appreciated that it ends in such an enthusiastic climax that left me cackling and cheering. It’s a mystery with a relatively satisfying answer but a climax that is also cathartic and exhale-inducing after all the dread and build-up.

The technical elements are just as polished as its knotty screenplay. The movie is genuinely unnerving at many points. Even the image of kids Narutu-running off into the night is inherently creepy. There are a few cheap jump scares but most of the movie is built around a quiet sense of desperation and dread. Cregger prefers holding onto shots to build tension, like a door opening and waiting for something, anything to pop out of the darkness. There are moments that made me wince and moments that made me gasp, like suddenly being compelled to stab one’s face with a fork dozens of times. However, a significant drawback for me was the lighting levels of the cinematography. To be clear, the photography was eerie and very evocative. My problem is that this was a movie whose light levels were so low it made it excruciatingly hard to simply identify what was happening onscreen. I’m sure my theater’s dim projection was part of this, but this is also a trend with modern movie-making, the murky lighting, like everyone is trying to recreate those Barry Lyndon’s candle-lit tableaus. Sometimes I just want to see what’s happening in my movie.

Weapons is certainly a thought-provoking premise, but with some distance from the movie, I’m starting to wonder what more there may be under the surface. Now not every movie has to be designed for maximum layers and themes and metaphors; movies can have their own points of appeal before getting to subtext. I do think most viewers will find Weapons engaging and intriguing, and the slippery structure helps make the movie feel new every twenty minutes while also testing out different tones that might have been too obtrusive with different characters and their specific perspectives. However, once you straighten out that timeline and see things clearly, it begs the question what exactly Cregger is actually saying. The sudden and disturbing horror of a classroom of children all disappearing has to have obvious connections to school shootings and mass killings, right? The trauma image is too potent and specifically tied to schools to be accidental or casual. Taking that, what is the movie saying about our culture where one day, any day, a class full of young children can just go missing? Despite a literal floating assault rifle appearing in a dream, there doesn’t appear to be much on the movie’s mind about gun violence or even weapons in general. I’m reminded of my favorite movie of 2020, the criminally under-seen Spontaneous, which explored a world where one high school class of students lived under the threat that at any time they could explode. There was no explanation for this strange phenomenon, though scientists certainly tried, and the focus was instead on the unfair dread hanging over their day-to-day existence, that at any moment their life could be forfeited. The parallel was obvious and richly explored about the pressure and anxieties of a life where this very disturbing reality is considered your accepted new normal. That was a movie with ideas and messages linking them to its school-setting of metaphorical trauma. I can’t say the same with Weapons.

I’ve read some people analyze each one of the characters as one of the stages of alcoholism, and I’ve read other people argue that the movie is an exploration of a town come undone through unexplainable trauma, but I seriously doubt that last one. Don’t you think the mystery of the missing class would draw national and international media attention? Hangers-ons thinking they cracked the case? Intruders harassing the bigger names? People trying to exploit a tragedy for money or a sense of self-importance? Conspiracy theorists linking this mystery to their other data points for a larger conspiracy? It doesn’t feel like the impact of this unique mystery has escaped the county lines. Certainly there are characters searching for answers and treating this poor schoolteacher as a scapegoat for their collective fears and anger, but by turning the screenplay into a relay race where one character hands off to the next for time in the spotlight, it doesn’t expand our sense of the town and the broader effects of this bizarre tragedy. Instead, it pens in the characters we do have, which all seem to interact with those very same characters, making the bigger world feel actually smaller. Narrowing the lens of perspectives makes it more difficult to articulate commentary about community breakdown in the face of uncertainty. The creative choices square with the central mystery and the nesting-doll structure, playing a game with the audience to discover the source of this incident, but once you discover that source, and once we reach our ending, you too may appreciate Cregger’s narrative sleight-of-hand but eventually wonder, “Is that all there is?” Maybe so.

Weapons is an effective and engaging follow-up for Cregger and confirms that whatever stories he feels compelled to tell in horror are worthy of watching, preferably with as little prior information as possible. You definitely feel you’re in the confidant hands of a natural storyteller who enjoys throwing out surprises and shock value. I have some grumbles about ultimately what might all be behind that intriguing mystery and the lack of foundational commentary that would permit multiple viewings of close analysis. Then again not every movie is meant to be a repeat viewing. Some movies are one-and-dones but still enjoyable, and that might best sum up Weapons. It’s sharp and cleverly designed but maybe lacking a finer point.

Nate’s Grade: B

Anatomy of a Fall (2023)

I was so looking forward to watching the French drama Anatomy of a Fall, nominated for five Oscars including Best Picture and Best Director for Justine Triet, that I had to track down the publicity department for Neon Studios and hound them to finally get my annual Neon screener box-set for critics. It took several weeks, and email chains, but thankfully the good folks at Neon supplied me with their screener box, like Christmas morning for a film critic. The surprise Oscar nominations only made me more eager to finally watch this movie. As Anatomy of a Fall played, and the criminal case became ever more complicated, shedding further light upon the characters and their stormy marriage, I found myself sitting closer and closer to my TV, finally sitting on the floor right in front of it. Part of this can be explained by trying to better read the subtitles, though truthfully half of the movie is in English, but the real reason was that I became absorbed, waiting anxiously to see where it could go next, what twist and turn would further reassess our fragile understanding of the events, the people, and the possible circumstances. The original screenplay is so thoroughly engaging, and with supremely talented acting and clever directing, that I knew I was in good hands to ensure my investment of 140 minutes wouldn’t be wasted.

Popular novelist Sandra Voyter (Sandra Huller) is talking with a female reporter about her process as they lounge in her home. They’re drinking, laughing, and then the loud sounds of a steel drum start echoing from upstairs, thanks to Sandra’s husband, Samuel (Samuel Maleski), who puts the song on repeat. He’s passive aggressively sabotaging the interview, and Sandra bids goodbye to the interviewer. Hours later Samuel is found on the ground outside with blood seeping from a head wound. The attic window is open, the same attic he was remodeling before presumably falling to his death. Did he take his own life or was foul play involved? Did Sandra actually kill her husband?

At its core, the movie is an anatomy of a criminal investigation, a prosecution and the personal defense, but it’s really an anatomy of people and the versions of themselves that they selectively present to others and themselves. It’s an old maxim that you can never know what’s going on inside a marriage, or really any relationship, as the inner reality is far more complex than what is easy to digest and categorize by the public. It’s not new to hide aspects of ourselves from wider scrutiny and consumption. It also isn’t new for a larger public profile to invite speculation from online busybodies who think they are entitled to know more. The mystery about whether or not Sandra is guilty or a cruel victim of suspicious circumstance is a question that Triet values, but clearly she values other more personal mysteries more, chiefly the mystery of our understanding of people and why they may choose to do inexplicable acts. How close can we ever really know a person? The upending of her life pushes Sandra to re-examine her own marriage in such a high stakes crucible that can determine whether or not she spends the rest of her life in jail. Under those extreme circumstances, the bigger question isn’t how someone may have committed murder, or taken their life, but the unexamined why of it all that nibbles away at Sandra as well as our collective consciousness as viewers. To me, that’s a more compelling and worthwhile mystery to explore than whether or not it was a murder or suicide (there is a wild theory finding some traction online blaming the death on the family dog).

I don’t feel it’s a significant spoiler to prepare the viewer to know that Triet keeps to ambiguity to the bitter end, refusing to specify what actually happened to Samuel. It’s ultimately up to the viewer to determine whether they think Sandra is guilty or innocent, and there’s enough room to have a debate with your friends and Francophile colleagues. I’ll profess that I found myself on the Team Sandra bandwagon and fully believed she was being railroaded by the French judicial system and press. The righteous anger I felt on behalf of this woman rose to volcanic levels, as it felt like much of the French prosecution’s line of questioning and theorizing was mired in blatant eye-rolling misogyny and conjecture. They insist that because Sandra is bisexual that she must have been flirting with her female interviewer on the day of Samuel’s death, because that’s how it works for bisexuals, obviously, to only be able to size every person they meet, no matter whatever anodyne circumstances, as some possible or inevitable sexual conquest. As an outsider to the French judicial system, I was intrigued just by how the trials are conducted, which seems far less formal despite the wigs and robes, where the accused can interrupt anytime to deliver speeches and question experts. I also appreciated how much attention Sandra’s family friend and defense attorney puts into helping her shape her image, to the press, to the court, to the judge, down to her perspective of her marriage to her vocabulary choices. Rather than be a reflection of Sandra as coolly calculated, I viewed it as learning to prepare for the dangers ahead. It reminded me of Gone Girl with the media-savvy lawyer coaching his high-profile client through their trouble.

Of course, there are larger implications with this prosecution. Sandra isn’t just on trial for suspicion of killing her husband to clear the way for her next lover, she’s the victim of all the ways that women are judged and found guilty by society. Sandra is a successful novelist, the top provider, and her husband isn’t, and it eats away at him, festering resentment that she is somehow stifling his own creative dreams. Is she giving him space or being distant? Is she doing enough or too little? Is she a supportive spouse or selfish? Is she a good mom or a bad mom? Is she allowed an independent life or should she be fully devoted to the titles of mom and wife? It’s the struggle to fit into everyone’s impossible and conflicting definition of what makes an acceptable woman and mother, and it’s infuriating to watch (think America Ferrera’s Barbie speech but as a movie). It’s also an indication of the cultural true crime obsession and turning people’s complicated identities and nuanced relationships into easy-to-digest fodder for morbid entertainment. It’s not like there’s some grand speech that positions Sandra as the martyr for all of embattled womanhood, but through her trial and media scrutiny, these social issues are projected onto her like a case study.

As much as I loved Lily Gladstone and Emma Stone in their respective performances in 2023, at this point I’d gladly give the Best Actress Oscar to Huller (The Zone of Interest). First off, she delivers a tremendous performance in three separate languages, as her character is a native German who marries a Frenchman and then they agree to speak in English as their linguistic “middle ground,” a language that isn’t native to either of them. Huller slips into her character seamlessly and it’s thrilling to watch her assert herself, press against the bad faith assumptions of others. One of the highlights of the movie is the most extended flashback where we witness the simmering resentment of this marriage come fully to force, and while it’s unclear whether this moment, as the other occasional flashbacks, is meant to be conveyed as Sandra’s subjective memory or objective reality, it serves as a mini-climax for the story. It’s here where Sandra pushes back against her husband’s self-pitying criticisms and projections. It’s a well-written, highly satisfying “Amen, sister” moment, and Huller crushes it and him. There were moments where I was in awe of Huller that I had to simply whistle to myself and remark how this woman is really good at acting. With such juicy material and layers to sift through, Huller astounds.

Another actor worth celebrating is Milo Machado-Graner (Waiting for Bojangles) as the couple’s only child Daniel, a young boy who is partially blind because of an earlier accident from Samuel’s negligence and the one who discovers his dad’s body. This kid becomes our entry point into the history of this marriage but it also turns on his perceptions of his parents, as Sandra is worried over the course of the trial that Daniel will learn aspects of their marriage that she was trying to shield from him, and he may never be able to see his father and mother the same way again. It’s a rude awakening for him, and key parts of the trial rest upon a child’s shaky memory, adding intense pressure onto a hurting little boy. There’s a key flashback that will change the direction of the case, but again Triet doesn’t specify whether this is Daniel’s memory, Daniel’s distorted memory looking for answers whereupon there might not be any, or the objective reality of what happened and what was said. Machado-Graner delivers a performance that is built upon such fragility that my heart sank for him. It’s a far more natural performance free of histrionics and easy exaggerations, making the response to such trying events all the more devastating.

Anatomy of a Fall was not selected by its home country for consideration for the Academy’s Best International Film competition despite winning the Palme D’Or, the top prize, at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival. Not to take anything away from 2023’s The Taste of Things, a French drama I’ve heard only fabulous responses, but clearly they picked the wrong contender and lost a winnable race. Do you know the last time France won the Oscar for Best Foreign/International Film? You have to go all the way back to 1991’s Indochine, a movie about the history of France’s colonial occupation of Vietnam. For a nation known for its rich history of cinema, it’s now been over thirty years since one of their own movies won the top international prize at the Academy. Oh well, there’s always next year, France. It’s truly befuddling because Anatomy of a Fall is such an easily accessible movie that draws you in and reveals itself with more tantalizing questions. It has supremely accomplished acting, directing, and writing. Anatomy of a Fall is a spellbinding, twisty movie and one of the absolute best films of 2023, in any language.

Nate’s Grade: A

Glass Onion (2022)

When writer/director Rian Johnson wanted to take a breather after his polarizing Star Wars movie, he tried his hand at updating the dusty-old Agatha Christie mystery genre, and in doing so created a highly-acclaimed and high-grossing film franchise. The man was just trying to do something different and at a smaller-scale with 2019’s Knives Out, and then it hit big and Netflix agreed to pay $400 million dollars for exclusive rights to two sequels. Now as Johnson has reinvented his career as a mystery writer the big question is: can he pull it all off again?

When writer/director Rian Johnson wanted to take a breather after his polarizing Star Wars movie, he tried his hand at updating the dusty-old Agatha Christie mystery genre, and in doing so created a highly-acclaimed and high-grossing film franchise. The man was just trying to do something different and at a smaller-scale with 2019’s Knives Out, and then it hit big and Netflix agreed to pay $400 million dollars for exclusive rights to two sequels. Now as Johnson has reinvented his career as a mystery writer the big question is: can he pull it all off again?

Renowned detective Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig) has been invited to the world’s most exclusive dinner party. Miles Bron (Edward Norton) has invited all his closest friends to his Greek island soiree, setting up a murder mystery game his friends must spend the weekend solving. Except there are two interlopers: Andi Brand (Janelle Monae), the former partner of Miles who was betrayed by Miles and his cronies and… Benoit Blanc himself. Why was the detective invited to the murder dinner party unless someone planned on using it as an excuse to actually kill Miles?

Knives Out was a clever deconstruction of drawing room mysteries and did something remarkable, it told you who the murderer was early and changed the entire audience participation. Instead of intellectually trying to parse clues and narrow down the gallery of suspects, Johnson cast that aside and said it didn’t matter as much as your emotional investment for this character now trying to cover up her tracks while working alongside the “world’s greatest detective.” It made the movie so much more engaging and fun, and for his twisty efforts, Johnson was nominated for a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. Now, every viewer vested in this growing franchise is coming into Glass Onion with a level of expectations, looking for the twists, looking for the clever deconstruction, and this time It feels like Johnson is deconstructing the very concept of the genius iconoclast and including himself in the mix. The movie takes square aim at the wealthy and famous who subscribe to the idea of their deserved privilege, in particular quirky billionaires whose branding involves their innate genius (many have made quick connections to Elon Musk in particular). The movie’s first half is taken with whether or not Miles Bron’s murder mystery retreat will become a legitimate murder mystery, but by the midpoint realignment, Glass Onion switches into pinning down the bastard. It makes for a greatly satisfying conclusion as Blanc exposes the empty center of Miles’ calculated genius mystique.

Knives Out was a clever deconstruction of drawing room mysteries and did something remarkable, it told you who the murderer was early and changed the entire audience participation. Instead of intellectually trying to parse clues and narrow down the gallery of suspects, Johnson cast that aside and said it didn’t matter as much as your emotional investment for this character now trying to cover up her tracks while working alongside the “world’s greatest detective.” It made the movie so much more engaging and fun, and for his twisty efforts, Johnson was nominated for a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. Now, every viewer vested in this growing franchise is coming into Glass Onion with a level of expectations, looking for the twists, looking for the clever deconstruction, and this time It feels like Johnson is deconstructing the very concept of the genius iconoclast and including himself in the mix. The movie takes square aim at the wealthy and famous who subscribe to the idea of their deserved privilege, in particular quirky billionaires whose branding involves their innate genius (many have made quick connections to Elon Musk in particular). The movie’s first half is taken with whether or not Miles Bron’s murder mystery retreat will become a legitimate murder mystery, but by the midpoint realignment, Glass Onion switches into pinning down the bastard. It makes for a greatly satisfying conclusion as Blanc exposes the empty center of Miles’ calculated genius mystique.

As Blanc repeatedly says, the answers are hiding in plain sight, and this also speaks to Johnson’s meta-commentary of his own clever screenwriting. This is Johnson speaking to the audience that he cannot simply copy the formula of Knives Out. This is a bigger movie with more broadly written characters, but each one of them feels more integrated in the central mystery and given flamboyant distinction; it’s more like Clue than Christie. Through Miles’ influence, we have a neurotic politician (Kathryn Hahn), a block-headed streamer (Dave Bautista) pandering to fragile men on the Internet, a fashionista (Kate Hudson) who built an empire on sweatpants and has a habit of insensitive remarks, and a business exec (Leslie Odom Jr.) who admits to sitting on his hands until given orders from on high by Miles. All of these so-called friends are really bottom-feeders propped up by Miles’ money. It would have been easy to simply replay his old tricks, but Johnson takes the heightened atmosphere of the characters and plays with wilder plot elements of the mystery genre, such as identical twins and secret missions and celebrity cameos (R.I.P. two of them) and corporate espionage. The very Mona Lisa itself plays significantly into the plot (fun fact: Ms. Mona was not the universally revered epitome of art we know it to be until its 1911 theft). This is a bigger, broader movie but the larger stage suits Johnson just fine. He adjusts to his new setting, veers into wackier comedy bits with aplomb, and has fun with all the false leads and many payoffs. You never know when something will just be a throwaway idea, like the hourly chime on the island, or have an unexpected development, like Jeremy Renner’s hot sauce. Glass Onion is about puncturing the mirage of cleverness, and by the end, it felt like Johnson was also playfully commenting on his own meta-clever storytelling needs as well.

As Blanc repeatedly says, the answers are hiding in plain sight, and this also speaks to Johnson’s meta-commentary of his own clever screenwriting. This is Johnson speaking to the audience that he cannot simply copy the formula of Knives Out. This is a bigger movie with more broadly written characters, but each one of them feels more integrated in the central mystery and given flamboyant distinction; it’s more like Clue than Christie. Through Miles’ influence, we have a neurotic politician (Kathryn Hahn), a block-headed streamer (Dave Bautista) pandering to fragile men on the Internet, a fashionista (Kate Hudson) who built an empire on sweatpants and has a habit of insensitive remarks, and a business exec (Leslie Odom Jr.) who admits to sitting on his hands until given orders from on high by Miles. All of these so-called friends are really bottom-feeders propped up by Miles’ money. It would have been easy to simply replay his old tricks, but Johnson takes the heightened atmosphere of the characters and plays with wilder plot elements of the mystery genre, such as identical twins and secret missions and celebrity cameos (R.I.P. two of them) and corporate espionage. The very Mona Lisa itself plays significantly into the plot (fun fact: Ms. Mona was not the universally revered epitome of art we know it to be until its 1911 theft). This is a bigger, broader movie but the larger stage suits Johnson just fine. He adjusts to his new setting, veers into wackier comedy bits with aplomb, and has fun with all the false leads and many payoffs. You never know when something will just be a throwaway idea, like the hourly chime on the island, or have an unexpected development, like Jeremy Renner’s hot sauce. Glass Onion is about puncturing the mirage of cleverness, and by the end, it felt like Johnson was also playfully commenting on his own meta-clever storytelling needs as well.

It’s so nice to watch Craig have the time of his life. You can clearly feel the passion he has for the character and how freeing this role is for an actor best remembered for his grimaced mug drifting through the James Bond movies. Craig makes a feast of this outsized character, luxuriating in the Southern drawl, the loquaciousness, and his befuddled mannerisms. After Knives Out, I begged for more Benoit Blanc adventures, and now with a successful sequel, that urge has only become more rapacious. Johnson has proven he can port his detective into any new mystery. Netflix has already paid for a third Knives Out mystery movie, and I’d be happy for another Blanc mystery every so many years as long as Craig and Johnson are willing. These are fabulous ensemble showcases as well with eclectic casts cutting loose and having fun. Norton (Motherless Brooklyn) is hilariously pompous, especially as Blanc deflates his overgrown ego. Bautista (Dune) is the exact right kind of blowhard. Hudson (Music) is the right kind of ditzy princess with a persecution complex. Her joke about sweatshops is gold. Jessica Henwick (The Gray Man) has a small role as the beleaguered assistant to Hudson’s socialite, but she delivers a masterclass in making the most of reaction shots. She made me laugh out loud just from her pained or bewildered reactions, adding history to her boss’ routine foot-in-mouth PR blunders.

There is one big thing missing from Glass Onion that holds it back from replicating the surprise success of its predecessor, and that’s the emotional lead supplied by Ana de Armas. She unexpectedly became the center of the 2019 movie and it was better for it. Glass Onion tries something similar with Andi Brand, and while she’s the easiest new character to root for among a den of phonies and sycophants, it’s not the same immediate level of emotional engagement. That’s the biggest missing piece for Glass Onion; it’s unable to replicate that same emotional engagement because the crusade of Andi Brand isn’t as compelling alone.

There is one big thing missing from Glass Onion that holds it back from replicating the surprise success of its predecessor, and that’s the emotional lead supplied by Ana de Armas. She unexpectedly became the center of the 2019 movie and it was better for it. Glass Onion tries something similar with Andi Brand, and while she’s the easiest new character to root for among a den of phonies and sycophants, it’s not the same immediate level of emotional engagement. That’s the biggest missing piece for Glass Onion; it’s unable to replicate that same emotional engagement because the crusade of Andi Brand isn’t as compelling alone.

Glass Onion is a grand time at the movies, or as Netflix insisted, a grand time at home on your streaming device. It’s proof that Johnson can handle the rigors of living up to increased expectations, making a sequel that can stand on its own but has the strong, recognizable DNA of its potent predecessor. It’s not quite as immediate and layered and emotionally engaging, but the results are still colorful, twisty, and above all else, immensely fun and satisfying. I’m sure I’ll only think better of Glass Onion upon further re-watching as I did with Knives Out. Johnson once again artfully plays around with misdirects and whodunnit elements like a seasoned professional, and Glass Onion is confirmation that Benoit Blanc can be the greatest film detective of our modern age.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Death on the Nile (2022)

I am admittedly not the world’s biggest Agatha Christie fan, so once again reader, as you did with my review of 2017’s Murder on the Orient Express remake, take my critique with caution, especially if you are a fan of the illustrious author’s many drawing room murder mysteries. Kenneth Branagh returns as director and as the world’s greatest detective, Hercule Poirot, with arguably the world’s greatest mustache (as I said in 2017, it appears like his mustache has grown its own mustache). Death on the Nile takes the murder-on-mode-of-transport formula and leaves us with a gaggle of red herrings and suspects to ponder until the inevitable big conclusion where our smartypants detective reveals everything we had no real chance of properly guessing no matter the clues. Again, these kinds of impossible-to-solve mysteries are not for me, but I know others still find antiquated pleasures with them (Christie was the best-selling author of the twentieth century after all). What I don’t find as pleasing, and I’m sure even ardent whodunit fans would agree, is how cheaply this whole production looks. The budget was almost twice as much as Orient Express but it’s really a chintzy-looking cruise ship with one of the most obvious green screens for a big budget film. It takes away from the grandeur quite a bit, especially knowing the original 1978 movie was shot on location in Egypt. Another aspect that didn’t work for me was the added back-story for Poirot, including the explanation for why he grew his preposterous mustache. Did we need a mustache origin story? Did I need an attempt to better humanize this fastidious detective? If you were a fan of the overly serious and stately Orient Express, and of Christie in general, I’m sure there’s enough to recommend a new Death on the Nile. Branagh clearly has passion for this character and as a steward of this cherished material. However, for me, it took too long to get the movie really rolling, the characters were too lackluster, and there are too many tonally bizarre and uncomfortable moments, like Gal Gadot quoting Cleopatra while being, I guess, dry humped by Armie Hammer against an Egyptian relic. As Poirot’s mustache, which will be given top-billing in the third film, would say, “Yikes.”

I am admittedly not the world’s biggest Agatha Christie fan, so once again reader, as you did with my review of 2017’s Murder on the Orient Express remake, take my critique with caution, especially if you are a fan of the illustrious author’s many drawing room murder mysteries. Kenneth Branagh returns as director and as the world’s greatest detective, Hercule Poirot, with arguably the world’s greatest mustache (as I said in 2017, it appears like his mustache has grown its own mustache). Death on the Nile takes the murder-on-mode-of-transport formula and leaves us with a gaggle of red herrings and suspects to ponder until the inevitable big conclusion where our smartypants detective reveals everything we had no real chance of properly guessing no matter the clues. Again, these kinds of impossible-to-solve mysteries are not for me, but I know others still find antiquated pleasures with them (Christie was the best-selling author of the twentieth century after all). What I don’t find as pleasing, and I’m sure even ardent whodunit fans would agree, is how cheaply this whole production looks. The budget was almost twice as much as Orient Express but it’s really a chintzy-looking cruise ship with one of the most obvious green screens for a big budget film. It takes away from the grandeur quite a bit, especially knowing the original 1978 movie was shot on location in Egypt. Another aspect that didn’t work for me was the added back-story for Poirot, including the explanation for why he grew his preposterous mustache. Did we need a mustache origin story? Did I need an attempt to better humanize this fastidious detective? If you were a fan of the overly serious and stately Orient Express, and of Christie in general, I’m sure there’s enough to recommend a new Death on the Nile. Branagh clearly has passion for this character and as a steward of this cherished material. However, for me, it took too long to get the movie really rolling, the characters were too lackluster, and there are too many tonally bizarre and uncomfortable moments, like Gal Gadot quoting Cleopatra while being, I guess, dry humped by Armie Hammer against an Egyptian relic. As Poirot’s mustache, which will be given top-billing in the third film, would say, “Yikes.”

Nate’s Grade: C

Mulholland Drive (2001) [Review Re-View]

Originally released October 19, 2001:

Mulholland Dr. has had a long and winding path to get to the state it is presented today. In the beginning it was 120 minutes of a pilot for ABC, though it was skimmed to 90 for the insertion of commercials. But ABC just didn’t seem to get it and declined to pick up David Lynch’s bizarre pilot. Contacted by the French producers of Lynch’s last film, The Straight Story, it was then financed to be a feature film. Lynch went about regathering his cast and filming an additional twenty minutes of material to be added to the 120-minute pilot. And now Mulholland Dr. has gone on to win the Best Director award at Cannes and Best Picture by the New York Film Critics Association.

Laura Harring plays a woman who survives a car crash one night. It appears just before a speeding car full of reckless teens collided into her limo she was intended to be bumped off. She stumbles across the dark streets of Hollywood and finds shelter in an empty apartment where she rests. Betty Elms (Naomi Watts) is a young girl that just got off the bus to sunny California with aspirations of being a big time movie star. She enters her aunt’s apartment to find a nude woman (Harring) in the shower. She tells Betty her name is Rita after glancing at a hanging poster of Rita Hayworth. Rita is suffering from amnesia and has no idea who she is, or for that fact, why her purse is full of thousands of dollars. Betty eagerly wants to help Rita discover who she is and they set off trying to unravel this mystery.

Across town, young hotshot director Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux) is getting ready to go into production for his new film. He angers his mob producers by refusing to cast their chosen girl for his movie. After some harassment, threats, and a visit by an eyebrow-less cowboy assassin (God bless you David Lynch), he relents.

In the meanwhile, people are tracking the streets looking for Rita. Betty and Rita do some detective work and begin amassing clues to her true identify. As they plunge further into their investigation the two also plunge into the roles of lovers. Rita discovers a mysterious blue box and key in her possession. After a night out with Betty she decides to open it, and just when she does and the audience thinks it has a hold on the film, the camera zooms into the abyss of the box and our whole world is turned upside down.

David Lynch has made a meditation on dreams, for that is at the heart of Mulholland Dr. His direction is swift and careful and his writing is just as precise. The noir archetypes are doing battle with noir expectations. The lesbian love scenes could have been handled to look like late night Cinemax fluff, but instead Lynch’s finesse pays off in creating some truly erotic moments. Despite the population of espresso despising mobsters, wheelchair bound dwarfs, and role-reversal lesbians, the audience knows that it is in hands that they can trust. It’s Lynch back to his glorious incomprehensible roots.

Watts is the true breakthrough of Lynch’s casting and she will surely be seen in more films. Watts has to play many facets of possibly the same character, from starry-eyed perky Nancy Drew to a forceful and embittered lesbian lover.

One scene stands out as a perfect example of the talent Watts possesses. Betty has just been shuffled off to an audition for a film and rehearsing with Rita all morning. She’s introduced to her leathery co-star and the directors await her to play out the audition scene of two kids and their forbidden love. As soon as the scene begins Betty vanishes and is totally inhabited by the spirit of her character. She speaks her lines in a breathy, yet whisper-like, voice running over with sensuality but also elements of power. In this moment the characters know, as the audience does, that Betty and Naomi Watts are born movie stars.

It’s not too difficult for a viewer to figure out what portions of the film are from the pilot and what were shot afterwards. I truly doubt if ABC’s standards and practices allows for lesbian sex. The pilot parts seem to have more sheen to them and simpler camera moves, nothing too fancy. The additional footage seems completely opposite and to great effect. Mulholland Dr. has many plot threads that go nowhere or are never touched upon again, most likely parts that were going to be reincorporated with the series.

The truly weirdest part of Mulholland Drive is that the film seems to be working best when it actually is still the pilot. The story is intriguing and one that earns its suspense, mystery, and humor that oozes from this noir heavy dreamscape. The additional twenty minutes of story could be successfully argued one of two ways. It could be said it’s there just to confound an audience and self-indulgent to the good story it abandons. It could also be argued that the ending is meticulously thought out and accentuates the 120 minutes before it with more thought and understanding.

Mulholland Dr. is a tale that would have made an intriguing ongoing television series complete with ripe characters and drama. However, as a movie it still exceeds in entertainment but seems more promising in a different venue.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

How much is a dream worth to you? That’s my main takeaway re-watching David Lynch’s surreal indie Mulholland Drive twenty years later from its release. Lynch has had plenty of his own run-ins with the dream makers of Tinseltown, from the difficulty to see his admittedly weird projects off the ground to the swift cancellation of his once zeitgeist, and deeply weird, TV series, Twin Peaks. It’s common knowledge now that Mulholland Drive began as a 1999 TV pilot that Lynch re-conceived as a movie, shot 30 minutes of additional footage, and earned a 2001 Best Directing Oscar nomination for his perseverance and creative adaptability. The movie has since taken on quite a reputation. The BBC and Los Angeles Society of Film Critics have both hailed it as the best film of the twenty-first century (so far). Lynch has retreated back to his insular world of weirdness with hypnotic, over-indulgent retreads, Inland Empire, and bringing back his signature TV series for a Showtime run in 2017. In 2001, Mulholland’s Drive’s success seemed to be the last point with Lynch working with the studio system he so despised. In a way, this is his farewell letter to chasing his own dreams of stardom, at least as far as a director can have creative control and a steady supply of protection and money to see his vision through. Watching Mulholland Drive is like stepping through a dream, which has been the hallmark of Lynch’s more celebrated, obtuse filmography from 1977’s Eraserhead onward. The movie is meant to operate on a certain dream logic, sustained with choices that seem artistically self-destructive, but the journey might feel as emotionally or intellectually fleeting as a dream as well, so I ask you, dear reader, to think as you continue, how much is a dream worth?

The failed pilot serves as a majority of the film’s running time and it’s filled with peculiar beginnings that will never pay off. There are actors like Robert Forster (Jackie Brown) and Brent Briscoe (Sling Blade) who show up for one whole scene and then are never seen again. Presumably, the roles would have been more significant as detectives snooping around from the peripheral. There are mysterious forces chasing after “Rita” (Laura Harring), an important-looking woman who has conveniently lost her memory and adopted her name after seeing a poster of Rita Hayworth. She’s got a bag filled with money, a gun, and blue key. One would assume over the course of a network season that we would get closer to discovering the real identity of our amnesiac leading lady. There are also scenes that seem to exist as their own short films, like the darkly comedic hapless hitman and the scared man detailing his spooky dream to a concerned friend in a diner. These characters, presumably, would come back for more significance or at least larger interplay. The same with the mysterious locked box and key. You can practically identify the J.J. Abrams “mystery box”-style of storytelling for future intrigue. The role of a TV pilot is to serve up a storytelling engine that can keep churning, as well as ensuring that there’s enough curiosity to hook an audience through commercial breaks. Lynch is used to inserting strange symbols and starts in his movies that potentially go nowhere, so the difference between a Lynch pilot and a Lynch movie aren’t terribly noticeable. These characters, clues, and moments were perhaps intended to be developed further, or perhaps they never were. It’s as if the movie itself is a nightmare of different television programs colliding incoherently.

There does seem to be a consensus interpretation for Mulholland Drive, one that synchs up the various doubles and symbols. For two hours, we’re riding along with Betty (Naomi Watts) as she moves to L.A. with big dreams and perky naivete. She finds the amnesiac Rita in her aunt’s apartment and takes it upon herself to give her a home and investigate her identity. They grow close together, Betty nails her big acting audition, and then Betty and Rita become lovers. They go to a club (Silencio) where performance artists insist “everything is recorded,” and thus already happened, phony, and a replication of memory, and then Rita inserts that mystery blue key into the mystery box and mysteriously vanishes. We next return to the scene of Diane, who at first was a dead body that Rita and Betty found during their investigation. Now it’s Betty, or at least Watts playing her, and she’s a struggling actress who is jealous of the success and favor her girlfriend, Camilla (also played by Harring), is indulging in from their seedy director, Adam (Justin Theroux). Overcome with torment, she hires a hitman to kill Camilla. From there, she’s attacked by a homeless monster, tiny versions of the people portraying Betty’s parents in the first part, and she takes her own life in grief and guilt. The most common interpretation is that the final twenty or so minutes with Watts as Diane is the real story and that the proceedings 110 minutes was Diane’s dream trying to process her guilty conscience and mixed emotions. The blue key, the symbol from Diane’s hired hitman of a job completed, is the point of transportation between the dream and returning to a living nightmare of regret. Adam’s prominence in the first two hours is explained as punishment from Diane’s mind, so this is why he is emasculated repeatedly, from being robbed of control over his movie, his marriage, and ultimately his future.

Just because this is the most prominent interpretation, and even perhaps the author’s intended one, doesn’t mean other viewers cannot find equally valid and differing interpretations. That’s the appeal or point of frustration with Lynch’s most Lynchian work. However, the problem with asserting that the first two hours of your two-hour-plus movie were all a dream can make it feel overindulgent and unsatisfying. The TV pilot segments are shot in a way that evokes the cliché storytelling stye that prevailed at the time, with overly lit scenes and flat acting. I cannot say for certain but it feels like Lynch purposely told Watts (King Kong) to try and be hammy. Lynch has been known to purposely ape the style of prime-time soaps to provide subtle satirical contexts. Is Watts doing a bad job with the purpose of making us think of other bad actors from soaps? The one scene Betty comes alive is during her audition scene. We’ve already seen her act it out once so we’re expecting more of the same, but in that moment, she comes alive with sensuality, taking control from the aged acting partner who was just there to exploit some young new starlets. The intensity she unleashes, a mixture of carnal desire and self-loathing, is nothing like bright-eyed Betty. Is the irony that when Betty is pretending to be someone else that’s when the performance excels? You can see the points for interpretation, especially considering the ending thesis, but if so, it’s such a bold gamble by Lynch that could prove so alienating. You’re deliberately having your lead actress act in a cliched and stilted manner to perhaps make a point fewer will grasp? Obviously, the ending wasn’t intended to pair with the pilot parts, so it feels like projecting an unintended meaning onto the intentions of acting decisions, but dreams are murky that way.

I wouldn’t be surprised if just as many people are tested by Mulholland Drive as they are mesmerized. It’s a combination of different genres and film iconography, from Manning as a living-breathing femme fatale, to dark whimsical comedy, to surreal mystery, to tawdry erotic drama, to industry-obsessed soap. As much as it feels like a pilot retooled into a new beast, it also feels like a collection of genres being retooled for whatever intended association Lynch wants to impart. It’s ready-made for dissection and ready to take apart the Hollywood studio system. I enjoyed some of the strange moments that felt most ancillary, like the mobster with the extremely refined taste for espressos, and the eyebrow-less cowboy assassin threatening Adam. That scene in particular still has an unsettling menace to it, as Lynch takes what could have been absurd and finds a way to make this man overtly threatening without ever explicitly doing anything threatening. His browbeating to Adam over the difference between listening and hearing is well written and ends perfectly: “You will see me one more time, if you do good. You will see me… two more times, if you do bad. Good night.” I wish more sequences like this could stand on their own. So much of Mulholland Drive seems intended to provide a skeleton for meaning to be provided later as the added meat that Lynch didn’t value as highly.

Watts became a star from this movie and was taken to another level with the success of 2002’s The Ring. From there, she was in the Hollywood system of stars and after toiling for ten years from rejected interviews to rejected interviews. She was thinking of quitting acting and going back to her native Australia at the time she got asked to play Betty/Diane. The audition scene, the later distraught and frail Diane, as well as the mannered Betty served as an acting reel for every casting agent that had rejected her. Here was Watts, capable of doing it all and then some (she was nominated for two Oscars – 2003’s 21 Grams and 2012’s The Impossible).

My original review in 2001 is also wrestling with the question over interpretation versus intention, with the genre mash-ups as symbolic satire or as laborious TV pandering. Mulholland Drive is like watching a dream and trying to dissect its many meanings. Some people will relish the puzzle pieces that Lynch has provided and finding further hidden mirrored meanings, and other people will throw up their hands and ask for a road map, or lose interest by then. I don’t think this is the best film of the first twenty years of this new century. I don’t even think it’s close. I think at its best it can be hypnotic and intriguing; it’s a shame that these are only moments for me, and twenty years later these moments felt even further spaced apart. I just didn’t find Lynch’s movie quite worth the long, surreal drive into the dark of his imagination.

Re-View Grade: B-

Old (2021)

Old, M. Night Shyamalan’s latest thriller, seems ripe for parody, perhaps even upon delivery in theaters. The “can’t even” bizarre energy of this movie is off the charts and bounces back and forth between hilarious camp and head-scratching seriousness with several frustrating and absurd artistic decisions by Shyamalan. If you viewed this movie as a strange comedy, then you would be right. If you viewed it as an existential horror movie, then you would be right. If you viewed it as a heightened satire on high-concept Twilight Zone parables, then you would be right.

We follow a family on a vacation to a Caribbean resort. Guy (Gael Garcia Bernal) and Prisca (Vicky Krieps) are keeping secrets from their two children, six-year-old Trent (Nolan River) and eleven-year-old Maddox (Alexa Swinton). The parents are planning on separating and Prisca has a tumor, though benign for the time being. The hotel manager offers an exclusive secluded beach for those who would really enjoy this special experience. Guy, Prisca, and their kids join another family with a six-year-old daughter, a married couple, and an old lady with her dog, and they drive off into the jungle. Except this beach is not what it appears to be. There are strange artifacts of past visitors, and every time people try and pass back through the path to leave, they pass out. Also, everyone is aging rapidly, about one year for every 30 minutes elapsed. The children become adults, the elderly succumb first, and everyone worries they may not ever leave.

Old is not one of Shyamalan’s worst movies but it’s hard to classify it as good without attaching conditional modifiers. It might be good, if you enjoy movies that are campy and schlocky. It might be good, if you enjoy movies that throw anything and everything out there just because. It might be good, if you enjoy movies that produce a supernatural concept, drop rules established whenever convenient, and then try to wrap everything up neatly with an absurdly thorough explanation for everything. It might be good, if you think Shyamalan peaked with 2006’s Lady in the Water. This is going to be a polarizing experience. I think Shyamalan doesn’t fully understand what tone he’s going for and how best to develop his crazy storyline in a way that makes it meaningful beyond the general WTF curiosity. Even when it goes off the rails, Old is entertaining but some of that is unintentional. There are points where it feels like Shyamalan is trying for camp and other points where it feels like he is aiming for something higher and just can’t help but stumble, Sisyphean-style, back again into the pit of camp absurdity.

The premise is a grabber and takes the contained thriller conceit that Hollywood loves for its cheap cost and applies a supernatural sheen. It’s based upon a French graphic novel, Sandcastle by Pierre-Oscar Levy and Frederik Peeters, though Shyamalan has taken several creative liberties. It’s an intriguing idea of rapid aging being the real trap, and it forces many characters to confront their own fears of mortality and aging but also parental failures. Every parent likely thinks with some degree of regret about how quickly their little ones grow up. These adults have to watch their children rapidly age in only hours and not have any way to stop the relentless speed of time. The extra level of fear is produced by the fact that mentally the children are still where they began that morning. Even as Trent ages into the body of a teenager, he still has the mind of a six-year-old, and that is a horror unto itself. As his body rapidly changes, his parents are helpless to stop this terrifying jolt into adulthood and unable to shield their child from the terror of physical maturation but being trapped in the mindset of a child who cannot keep up with their mutating body. There are definite body horror and existential dread potential here, though Shyamalan veers too often into lesser schlocky thriller territory. For him, it’s more the mystery or the foiled escape attempts than actually dwelling on the emotional anxiety of the unique predicament. There’s enough born from this premise that it keeps you watching to the end, even as you might be questioning the actions of the characters, their ability to somehow miraculously guess the right answers as a group about what is happening, and the inconsistency of the rules about what can and cannot happen on this accursed beach.

There is one sequence that deserves its own detailed analysis for just how truly bizarre and avoidable it could have been, and to do so I will need to invoke the warning of spoilers for this paragraph. One of the other six-year-olds, Kara, gets a whole traumatic experience all her own that is morally and artistically questionable. Midway through the movie, Kara (Eliza Scanlan) and Trent (Alex Wolff) come back from a jaunt off screen together and they’re older and Kara is clearly pregnant. Given the rules that were established, that means that these six-year-old children experimented with their newly adult bodies to the point of fertilization (oh God, writing this makes me wince). I must reiterate that these characters are still six-years-old. Before you start realizing the gross implications, Kara is quickly entering labor and within seconds the baby is suddenly born and within seconds the baby just as suddenly dies silently from, what we’re told, was a lack of attention. What he hell, Shyamalan? Did you have to throw a dead baby into your movie to make us feel the visceral horror of the situation? It feels tacky and needlessly triggering for some moviegoers. This entire sequence doesn’t impact the plot in any meaningful way. Kara could have died in childbirth because of the circumstances of the beach. That would be tragic but matter. Just having her get suddenly pregnant and then suddenly the recipient of a deceased child seems needlessly cruel and misguided. And then, in the aftereffect of this trauma, Kara’s mom tearfully recounts her first love, a man she still thinks about to this day but doesn’t understand why. What does this have to do with anything? Re-read this entire scenario and let it sink in how truly uncomfortable and gross it comes across. It could have been avoided, it could have even been better applied to the characters and themes of the story, but it’s empty, callous shock value.

Another hindrance of Old is that the characters lack significant development and nobody ever talks like a recognizable human being. As Shyamalan has embraced being more and more an unabashedly genre filmmaker, he’s lost sight on how to write realistic people. You see this throughout 2008’s The Happening with its curious line readings and clunky, inauthentic dialogue being legendary and unintentionally hilarious (“You should be more interested in science, Jake. You know why? Because your face is perfect.”). I feel like Old is the most reminiscent of The Happening, the last time Shyamalan went for broke with ecological horror. The way these characters talk, it sounds like their dialogue was generated by an A.I. instead. “You have a beautiful voice. I can’t wait to hear it when you’re older,” Prisca says, which is a strange way for a parent to say, “I like what you have but wishing it was better.” She also has the line to her husband, “When you talk about the future, I don’t feel seen.” There’s also a running theme of characters just blurting out their occupations as introductions, “I’m a doctor,” followed by, “I’m a nurse,” like it’s career day on the beach. Frustratingly, all the characterization ends once the people wind up on this fated beach. Many of these characters are simply defined by their maladies and professions. This character has seizures. This character has a blood disorder. This character has a tumor. This character has MS. Noticing a pattern? You would expect that with such a unique and challenging conflict that it would better reveal these people, push them to make changes, especially as change is thrust upon them whether they like it or not. Imagine your uncle being cursed with rapid aging but all he does is still complain about his lousy neighbor. That limited tunnel vision is what Old struggles with. And one of the characters is a famous rapper named Mid-Sized Sedan but without a hint or irony or showbiz satire. Mid-Sized Sedan!

The way Shyamalan shoots this movie also greatly increases its camp appeal. This movie is coursing with energy and contrarianism. Shyamalan is often moving his camera in swooping pans and finding visual arrangements that can be frustrating and obtuse. Sometimes it works, like when we have the child characters with their backs to the camera and we’re anticipating how they have changed and what they might look like. Too often, it feels like Shyamalan trying to interject something more into a scene like he’s unsure that the dramatic tension of the writing is enough. There are scenes where what’s important almost seems incidental to the visual arrangement of the shot. Some of the sudden push-ins and arrangements made me laugh because it took me out of the moment by making the moment feel even more ridiculous. This heightened mood to the point of hilarity is the essence of camp and that’s why it feels like Shyamalan can’t help himself. If he’s trying to dig for something deeper and more profound, it’s not happening with his exaggerated and mannered stylistic choices being a distraction.

The ending, which I will not spoil, tries to do too much in clearing up the central mysteries. It feels overburdened to the point of self-parody, having characters pout expository explanations for all that came before and supplying motivation as to what was happening. Still, Shyamalan cannot keep things alone, and he keeps extending his conclusion with more and more false endings to complicate matters; the more he attempts to tidy up the less interesting the movie becomes. I would have been happy to accept no explanation whatsoever for why the beach behaves as it does. The best Twilight Zone episodes succeed from the mystery and development rather than the eventual explanation (“Oh, it was all a social experiment/nightmare/whatever”). Once you begin to pick apart the explanation with pesky questions, the illusion of its believability melts away. I had the same issue with 2019’s Us. The more Jordan Peele tried to find a way to explain his underground doppelganger plot, the more incredulous and sillier it became.