Blog Archives

West Side Story (2021)

Steven Spielberg, now approaching seventy-five years of age, has experienced such rarefied success as a film director that the man can do whatever he wants. It just so happens he wanted to tackle his first big screen musical, something he’s a little late on considering peers like Martin Scorsese (1977’s New York, New York) and Francis Ford Coppola (1982’s One from the Heart) beat him to the musical punch early. The question isn’t why direct a musical at this stage of his glorious career, it’s why direct a remake of 1961’s Best Picture-winning West Side Story? We already have a perfectly good and revered movie version, and there are other musicals that haven’t even gotten their first big shining moment on the silver screen, so why go back to this particular show a second time?

Steven Spielberg, now approaching seventy-five years of age, has experienced such rarefied success as a film director that the man can do whatever he wants. It just so happens he wanted to tackle his first big screen musical, something he’s a little late on considering peers like Martin Scorsese (1977’s New York, New York) and Francis Ford Coppola (1982’s One from the Heart) beat him to the musical punch early. The question isn’t why direct a musical at this stage of his glorious career, it’s why direct a remake of 1961’s Best Picture-winning West Side Story? We already have a perfectly good and revered movie version, and there are other musicals that haven’t even gotten their first big shining moment on the silver screen, so why go back to this particular show a second time?

Once again, we’re following the two New York City street gangs, the Jets, who are made up of Italian and Irish white kids, and the Sharks, made up of Puerto Ricans. Tony (Ansel Elgort) is trying to reform his ways after spending a year in prison for gang violence. The Jets are pleading with him to get back involved, to push back against the Sharks encroaching on their territory. He meets Maria (Rachel Ziegler) at a dance and the two fall instantly in love. The problem is that Maria is Puerto Rican, her brother is the leader of the Sharks, and this relationship would be forbidden and dangerous. Tony and Maria plan to run away together and escape the conflicts of this tragic turf war.

I’ll risk musical theater heresy and admit outright that Spielberg’s West Side Story actually improves on the much-hallowed 1961 original in several ways. The most immediate and obvious is that we have Hispanic actors playing Hispanic characters. No regrettable brown face including the actual Hispanic actors this time (it’s just humiliating to watch Rita Moreno, in her Oscar-winning role, have to be darkened up to be “more Puerto Rican”). That’s a pretty good improvement already, though it’s not unexpected; 1961 was also the year Breakfast at Tiffany’s was released with its notorious Mickey Rooney performance in jaw-dropping yellow face. Granted, jaw-dropping today, not so back then. 1961 was still only a few years removed from John Wayne taping his eyelids back to portray Genghis Khan. This was the unfortunate norm.

I’ll risk musical theater heresy and admit outright that Spielberg’s West Side Story actually improves on the much-hallowed 1961 original in several ways. The most immediate and obvious is that we have Hispanic actors playing Hispanic characters. No regrettable brown face including the actual Hispanic actors this time (it’s just humiliating to watch Rita Moreno, in her Oscar-winning role, have to be darkened up to be “more Puerto Rican”). That’s a pretty good improvement already, though it’s not unexpected; 1961 was also the year Breakfast at Tiffany’s was released with its notorious Mickey Rooney performance in jaw-dropping yellow face. Granted, jaw-dropping today, not so back then. 1961 was still only a few years removed from John Wayne taping his eyelids back to portray Genghis Khan. This was the unfortunate norm.

Another immediate improvement is the visual dynamism of 60 years of technical filmmaking advancement. I recently re-watched the 1961 original, a film I haven’t watched since probably the 1990s as a teenager, and it’s a relatively good movie but it’s also a good movie of its time, and by that I mean there are limitations to the presentation. One of the most appealing aspects of movie musicals is how they expand upon our humdrum reality, the splashes of color and synchronicity and bold imagination. I’m not saying the movie musicals of the 1960s were particularly lacking, as there are many classics and favorites, but because of filmmaking practicalities and predilections, movies could only go so far at the time. With 60 years of technological advancements, today’s movie musicals, when under the right guidance, can expand the world of song-and-dance fantasy like few of the past. You need only compare the showstopper “America” in both films, the dancing high-point of either film. The original is on a rooftop for its entire duration. The new version is all over the city block, finally culminating on a crossroads and bringing the denizens of the town out in girl power empowerment. It’s such a high-energy and celebratory sequence and the scale and variance really make it feel so much more joyous and exciting. The choreography is also an improvement. Again, not a slight against the 1961 original, but in the ensuing 60 years we’ve also advanced in the technical precision and creativity of dancers. The 2021 West Side Story is impressive top to bottom with the dancing of all the performers, and with Spielberg as director, he wants you to best appreciate their talents while also making the movie as visually dynamic as he can.

Spielberg proves an absolute natural at helming a big movie musical. Nothing against Robert Wise, the 1961 director who helmed plenty of influential Hollywood titles like The Sound of Music, The Day the Earth Stood Still, I Want to Live, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. He was also the editor on Citizen Kane. The man clearly knew how to tell a big screen story across multiple genres. It’s not a shame to say his visual prowess doesn’t quite stack up to a Steven Spielberg, who just happens to be one of the most popular and versatile filmmakers of all time. Spielberg’s camera is much more active than the original movie, and he’s consistently bringing us into the scene, having characters duck in and out of frame, and circling around, always interacting with the world. It makes the movie much more visually immersive and exciting, enlivening an already lively number like the dance hall rivalry between the Jets and the Sharks where each side crowds the edges. The movie operates on a high level of visual pleasure because Spielberg knows exactly how to play to the strengths of the musical genre. Spielberg incorporates the location in each setting and has fun visual flourishes, clearly having given great thought how to visualize every line in each song. The opening of “America” involves women placing clothes on a line, and as the clothes move, it reveals our newest chorus member giving voice to the continuing song. The way the camera moves through the neighborhood to note the encroachment of gentrification. The way he frames the faces of our young lovers. The way he uses shadows as menace. The way he makes every space feel like it’s perfectly utilized for the best shots and edits. Now that Spielberg has proven so adept at handling musicals, somebody please give this man another for our collective benefit.

Spielberg proves an absolute natural at helming a big movie musical. Nothing against Robert Wise, the 1961 director who helmed plenty of influential Hollywood titles like The Sound of Music, The Day the Earth Stood Still, I Want to Live, and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. He was also the editor on Citizen Kane. The man clearly knew how to tell a big screen story across multiple genres. It’s not a shame to say his visual prowess doesn’t quite stack up to a Steven Spielberg, who just happens to be one of the most popular and versatile filmmakers of all time. Spielberg’s camera is much more active than the original movie, and he’s consistently bringing us into the scene, having characters duck in and out of frame, and circling around, always interacting with the world. It makes the movie much more visually immersive and exciting, enlivening an already lively number like the dance hall rivalry between the Jets and the Sharks where each side crowds the edges. The movie operates on a high level of visual pleasure because Spielberg knows exactly how to play to the strengths of the musical genre. Spielberg incorporates the location in each setting and has fun visual flourishes, clearly having given great thought how to visualize every line in each song. The opening of “America” involves women placing clothes on a line, and as the clothes move, it reveals our newest chorus member giving voice to the continuing song. The way the camera moves through the neighborhood to note the encroachment of gentrification. The way he frames the faces of our young lovers. The way he uses shadows as menace. The way he makes every space feel like it’s perfectly utilized for the best shots and edits. Now that Spielberg has proven so adept at handling musicals, somebody please give this man another for our collective benefit.

The top actors are not the leads but two very mesmerizing supporting players. Ariana DeBose, previously seen as one of the ensemble members in 2020’s Hamilton, is pure dynamite as Anita. She explodes with verve and personality and attitude and vibrant life, and the camera loves every second she’s on screen. She gets the bigger emotional arc than Maria. She gets the jubilant song, the aforementioned “America,” and gets her crushing moments of heartache as well. DeBose is phenomenal, and likewise so is Mike Faist (Panic) as the leader of the Jets. Like Anita, this character is brimming with anger and attitude and the movie does a much better job than the 1961 film of presenting him with a point of view that can develop some empathy. Faist is lanky yet so smooth in his movements, and he gets more dancing than just about anyone. He’s balletic in his dancing while still upholding his spiky attitude. Both of these actors are so self-assured in their roles, so vulnerable behind the surface, and so accomplished with their dancing and singing that one wishes the movie would devote more time to both of them.

As for our leads, Ziegler and Elgort (Baby Driver) are good but unexceptional as our naifs in love. Ziegler can sing beautifully and definitely has a natural innocence to her appearance. Her eyes are so large and glassy that she reminded me of an animated character at points. Elgort is solid in his singing but I can’t help but feel that he’s been lapped by his co-stars. There is a comic relief musical number, “Gee Officer Krupke,” where the various Jets have fun imitating the nay-saying adults who hastily cast judgement upon these juvenile delinquents. It’s a silly number about guys goofing around and could easily be the first on the chopping block to be cut for time. However, over the course of this fun diversion, I realized that person-to-person in the Jets crew, the same guys that just appeared as background players to fill out a scene previously, how good every person is, and how much more time I wish they had gotten than Elgort. Part of this is that the romance aspect of West Side Story has always been the weakest part of the show. It’s based upon Romeo and Juliet and tied to those tragic plot events, but when both Maria and Tony are ready to run away and marry one another after a single night, and especially after the fateful rumble where Maria is so astonishingly quick to forgiveness (and horniess), the romance plays so incredulously. As a result, the two lovers are essential to the story but also the most boring characters too.

As for our leads, Ziegler and Elgort (Baby Driver) are good but unexceptional as our naifs in love. Ziegler can sing beautifully and definitely has a natural innocence to her appearance. Her eyes are so large and glassy that she reminded me of an animated character at points. Elgort is solid in his singing but I can’t help but feel that he’s been lapped by his co-stars. There is a comic relief musical number, “Gee Officer Krupke,” where the various Jets have fun imitating the nay-saying adults who hastily cast judgement upon these juvenile delinquents. It’s a silly number about guys goofing around and could easily be the first on the chopping block to be cut for time. However, over the course of this fun diversion, I realized that person-to-person in the Jets crew, the same guys that just appeared as background players to fill out a scene previously, how good every person is, and how much more time I wish they had gotten than Elgort. Part of this is that the romance aspect of West Side Story has always been the weakest part of the show. It’s based upon Romeo and Juliet and tied to those tragic plot events, but when both Maria and Tony are ready to run away and marry one another after a single night, and especially after the fateful rumble where Maria is so astonishingly quick to forgiveness (and horniess), the romance plays so incredulously. As a result, the two lovers are essential to the story but also the most boring characters too.

I think the adaptation by Spielberg screenwriting stalwart Tony Kushner (Munich, Lincoln) has smartly updated plenty of political elements, amplifying racial tensions but looking at it over a broader scope. Giving Tony a mentor figure in an older woman who runs her drug store shop, played by Moreno, is a great choice, especially as she represents a medium between the two sides as she is Puerto Rican but her deceased husband was white. It’s smart to have someone from the community and so wise to try and impart lessons to Tony, especially as he wants to change for the better. One update from Kushner didn’t quite jibe for me and felt like token-ism. The youngest member of the Jets, a prepubescent pipsqueak, has been replaced with a trans man fighting for membership. I understand the basic character arc is the same, the outsider trying to be accepted by the group, but the consideration of trans acceptance in the 1960s wasn’t exactly enlightening. The other Jets tease and question the gender identity of the trans man, but this perspective never feels well integrated into the play’s prejudicial world. I suppose more could have been done like having the Sharks harass this character, belittling them over their identity, and then the Jets feeling like one of their own had been attacked and in that they would finally be accepted. Except this inclusion would be around the degradation and potential assault of a trans person, which itself is not the best reason to include a trans character if you’re just setting them up for trauma. I don’t know. This character could have easily been removed if this was all there was.

One other aspect I found cumbersome was the creative decision to not include English subtitles during the Spanish-speaking portions of the movie. I cannot understand the artistic rationale for this at all. Sure, Spanish-speaking viewers will be fine, and I could piece enough together with context clues and my rudimentary understanding of like 75 Spanish words, but what are we accomplishing here? It just feels alienating, and it inadvertently likens the viewing experience to what the Jets are going through, feeling like they cannot fully understand their new neighbors. I doubt that Spielberg and company wanted to reinforce the perspective of xenophobia, but purposely removing a key portion of your movie from the majority audience in the U.S. seems so strange to me. If it was just scant conversations or moments, I’d excuse it, but the untitled Spanish accounts for like ten percent of the whole movie. Imagine watching any foreign movie without the subtitles on screen. How much meaning are you able to devise on your own?

One other aspect I found cumbersome was the creative decision to not include English subtitles during the Spanish-speaking portions of the movie. I cannot understand the artistic rationale for this at all. Sure, Spanish-speaking viewers will be fine, and I could piece enough together with context clues and my rudimentary understanding of like 75 Spanish words, but what are we accomplishing here? It just feels alienating, and it inadvertently likens the viewing experience to what the Jets are going through, feeling like they cannot fully understand their new neighbors. I doubt that Spielberg and company wanted to reinforce the perspective of xenophobia, but purposely removing a key portion of your movie from the majority audience in the U.S. seems so strange to me. If it was just scant conversations or moments, I’d excuse it, but the untitled Spanish accounts for like ten percent of the whole movie. Imagine watching any foreign movie without the subtitles on screen. How much meaning are you able to devise on your own?

West Side Story 2021 is a good time for fans of musical theater and a testament that just because something is old and beloved doesn’t mean it can’t even be improved upon with the right people and goals. Both movies are about the same length, 150 minutes, which seems the de facto standard for movies this holiday season, and you’d have a good time with either. I think the updated version adds more visual creativity, impressive choreography, and remodeled racial and political considerations to make it land better for modern audiences. It might not have been needed but I’m glad all the same we now have two West Side Story movie musicals to cheerfully tap along to.

Nate’s Grade: B+

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001) [Review Re-View]

Originally released June 29, 2001:

Originally released June 29, 2001:

A.I. is the merger of two powerhouses of cinema – Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg. The very mysterious film was given to Spielberg by Kubrick himself who thought ole’ Steven would be a better fit to direct it. The two did keep communication open for like a decade on their ideas for the project until Kubrick’s death in March of 1999. What follows is an imaginative futuristic fairy tale that almost grabs the brass ring but falls short due to an inferior ending. More on that later.

In the future technological advances allow for intelligent robotic creatures (called “mechas”) to be constructed and implemented in society. William Hurt has the vision to create a robot more real than any his company has ever embarked on before. He wants to make a robot that can know real love. Flash ahead several months to Henry and Monica Swinton (Sam Robards and Frances O’Conner) who are dealing with their own son in an indefinite coma. Henry is given the opportunity to try out a prototype from his company of a new mecha boy. His wife naturally believes that her son could not be replaced and her emotions smoothed over. Soon enough they both decide to give the boy a try and on delivery comes David (Haley Joel Osment) ready to begin new life in a family. David struggles to fit in with his human counterparts and even goes to lengths to belong like mimicking the motions of eating despite his lack of need to consume. Gradually David becomes a true part of the family and Monica has warmed up to him and ready to bestow real love onto their mecha son.

It’s at this point when things are going well for David that the Swinton’s son Martin comes out of his coma and returns back to his parents. Sibling rivalry between the two develops for the attention and adoration of their parents. Through mounting unfortunate circumstances the Swintons believe that David is a threat and decide to take him away. The corporation that manufactured David had implicit instructions that the loving David if desired to be returned had to be destroyed. Monica takes too much pity on David that she ditches him in the woods and speeds off instead of allowing him to be destroyed.

It’s at this point when things are going well for David that the Swinton’s son Martin comes out of his coma and returns back to his parents. Sibling rivalry between the two develops for the attention and adoration of their parents. Through mounting unfortunate circumstances the Swintons believe that David is a threat and decide to take him away. The corporation that manufactured David had implicit instructions that the loving David if desired to be returned had to be destroyed. Monica takes too much pity on David that she ditches him in the woods and speeds off instead of allowing him to be destroyed.

David wanders around searching for the Blue Fairy he remembers from the child’s book Pinocchio read to him at the Swinton home. He is looking for this magical creature with the desire she will turn him into a real boy and his human mother will love him again. Along David’s path he buddies up with Gigolo Joe (Jude Law), a pleasure ‘bot that tells the ladies they’re never the same once he’s through. The two traverse such sights as a mecha-destroying circus called ‘Flesh Fairs’ complete with what must be the WWF fans of the future, as well as the bright lights of flashy sin cities and the submerged remains of a flooded New York. David’s journey is almost like Alice’s, minus of course the gigolo robot of pleasure.

There are many startling scenes of visual wonder in A.I. and some truly magical moments onscreen. Spielberg goes darker than he’s even been and the territory does him good. Osment is magnificent as the robotic boy yearning to become real, but Jude Law steals the show. His physical movement, gestures, and vocal mannerisms are highly entertaining to watch as he fully inhibits the body and programmed mind of Gigolo Joe. Every time Law is allowed to be onscreen the movie sparkles.

It’s not too difficult to figure out which plot elements belong to Spielberg and which belong to Kubrick, since both are almost polar opposites when it comes to the feelings of their films. Spielberg is an idealistic imaginative child while Kubrick was a colder yet more methodical storyteller with his tales of woe and thought. The collaboration of two master artists of cinema is the biggest draw going here. A.I.‘s feel ends up being Spielberg interpreting Kubrick, since the late great Stanley was dead and gone before he could get his pet project for over a decade ready. The war of giants has more Spielberg but you can definitely tell the Kubrick elements running around, and they are a gift from beyond the grave.

It’s not too difficult to figure out which plot elements belong to Spielberg and which belong to Kubrick, since both are almost polar opposites when it comes to the feelings of their films. Spielberg is an idealistic imaginative child while Kubrick was a colder yet more methodical storyteller with his tales of woe and thought. The collaboration of two master artists of cinema is the biggest draw going here. A.I.‘s feel ends up being Spielberg interpreting Kubrick, since the late great Stanley was dead and gone before he could get his pet project for over a decade ready. The war of giants has more Spielberg but you can definitely tell the Kubrick elements running around, and they are a gift from beyond the grave.

I thought at one point with the first half of A.I. I was seeing possibly the best film of the year, and the second half didn’t have the pull of the first half but still moves along nicely and entertained. But then came the ending, which ruined everything. There is a moment in the film where it feels like the movie is set to end and it would’ve ended with an appropriate ending that could have produced lingering talk afterwards. I’m positive this is the ending Kubrick had in mind. But this perfect ending point is NOT the ending, no sir! Instead another twenty minutes follows that destroys the realm of belief for this film. The tacked on cloying happy ending feels so contrived and so inane. It doesn’t just stop but keeps going and only gets dumber and more preposterous form there. I won’t go to the liberty of spoiling the ending but I’ll give this warning to ensure better enjoyment of the film: when you think the movie has ended RUN OUT OF THE THEATER! Don’t look back or pay attention to what you hear. You’ll be glad you did later on when you discover what really happens.

The whole Blue Fairy search is far too whimsical for its own good. It could have just been given to the audience in a form of a symbolic idea instead of building the last half of the film for the search for this fictional creature’s whereabouts. The idea is being pounded into the heads of the audience by Spielberg with a damn sledge hammer. He just can’t leave well enough alone and lets it take off even more in those last atrocious twenty minutes.

A.I. is a generally involving film with some wonderfully fantastic sequences and some excellent performances. But sadly the ending really ruins the movie like none other I can remember recently. What could have been a stupendous film with Kubrick’s imprint all over turns out to be a good film with Spielberg’s hands all over the end.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

There are two aspects that people remember vividly about A.I.: Artificial Intelligence and that’s the fascinating collaboration of two of the most influential filmmakers of all time and its much-debated and much-derided extended ending. Before we get into either, though, a fun fact about its very helpful title for Luddites. Originally the title was only going to be A.I. but the studio found that test audiences were confused by the two-word abbreviation and several clueless souls thought it was the number one and not the capital letter “I.” The studio didn’t want their high-concept meeting of cinematic masters to be confused with a popular steak sauce.

In the realm of cinematic titans, Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick rise to the top for their artistic ambitions, innovations, versatility, and great influence on future generations, but you’d be hard-pressed to see a uniquely shared sensibility. Kubrick’s films are known for his detached, mercurial perspective, flawless technical execution, leisurely pacing, and a pessimistic or cynical view of humanity. Spielberg’s films are known for their blockbuster populism, grand imagination and whimsy, as well as the director’s softer, squishier, and more sentimental view of humanity. It almost feels like a mixture of oil and water with their contradictory sensibilities. And yet Kubrick and Spielberg developed A.I. for decades, starting in the late 1970s when Kubrick optioned the short story “Super-Toys Last All Summer Long” by Brian Aldiss. Kubrick felt that Spielberg was a better fit for director in the mid-1980s, but Spielberg kept trying to convince Kubrick to direct. Both took on other projects and kept kicking A.I. down the road, also because Kubrick was dissatisfied with the state of special effects to conceive his “lifelike” robot boy. Kubrick died in early 1999 and Spielberg elected to finally helm A.I. and finish their creative partnership. He went back to the original 90-page treatment Kubrick developed with sci-fi novelist Ian Watson and wrote the final screenplay, Spielberg’s first screenwriting credit since Close Encounters of the Third Kind (and his only one since 2001). I view the final movie as a labor of love as Spielberg’s ode to Kubrick and his parting gift to his fallen friend.

Watching A.I. again, it is a recognizable Kubrick movie but through the lens of Spielberg’s camera and budget. In some ways, it feels like Spielberg’s two-hour-plus homage to his departed mentor. The movie moves gradually and gracefully and, with a few delicate turns, could just as easily be viewed as a horror movie than anything overtly cloying or maudlin. The opening 45 minutes introduces a family whose child is comatose with some mystery illness and the likelihood he may never return to them. The husband (Sam Robards) is gifted with a shiny new robot boy, David (Haley Joel Osment), as a trial from his big tech boss (William Hurt) who wants to see if he can make a robot child who will love unconditionally. The early scenes with David integrating into the family play like a horror movie, with the intruder inside the family unit, and David’s offhand mimicry of trying to fit in can make you shudder. All it would take is an ominous score under the scenes and they play completely differently. One scene, which is played as an ice breaker, is when David, studying his parents at the dinner table, breaks out into loud cackling laughter. It triggers his parents to laugh alongside him, but it’s so weird and sudden and creepy. David’s non-blinking, ever-eager presence is off-putting and creepy and Monica (Frances O’Connor), the mother, is rightfully horrified and insulted by having a “replacement child.” However, her emotional neediness steadily whittles away her resistance and she elects to have David imprint. This is a no-turning-back serious decision, having David imprint eternal love and adoration onto her, and if she or her husband were to change their minds, David cannot be reprogrammed. He would need to be disassembled. With this family, David is more or less a house pet kept around for adoration and then discarded when he no longer serves the same comforting alternative. Once the couple’s biological child reawakens, it’s not long before jealousy and misunderstanding lead David to being ditched on the side of the road as an act of “mercy.”

Watching A.I. again, it is a recognizable Kubrick movie but through the lens of Spielberg’s camera and budget. In some ways, it feels like Spielberg’s two-hour-plus homage to his departed mentor. The movie moves gradually and gracefully and, with a few delicate turns, could just as easily be viewed as a horror movie than anything overtly cloying or maudlin. The opening 45 minutes introduces a family whose child is comatose with some mystery illness and the likelihood he may never return to them. The husband (Sam Robards) is gifted with a shiny new robot boy, David (Haley Joel Osment), as a trial from his big tech boss (William Hurt) who wants to see if he can make a robot child who will love unconditionally. The early scenes with David integrating into the family play like a horror movie, with the intruder inside the family unit, and David’s offhand mimicry of trying to fit in can make you shudder. All it would take is an ominous score under the scenes and they play completely differently. One scene, which is played as an ice breaker, is when David, studying his parents at the dinner table, breaks out into loud cackling laughter. It triggers his parents to laugh alongside him, but it’s so weird and sudden and creepy. David’s non-blinking, ever-eager presence is off-putting and creepy and Monica (Frances O’Connor), the mother, is rightfully horrified and insulted by having a “replacement child.” However, her emotional neediness steadily whittles away her resistance and she elects to have David imprint. This is a no-turning-back serious decision, having David imprint eternal love and adoration onto her, and if she or her husband were to change their minds, David cannot be reprogrammed. He would need to be disassembled. With this family, David is more or less a house pet kept around for adoration and then discarded when he no longer serves the same comforting alternative. Once the couple’s biological child reawakens, it’s not long before jealousy and misunderstanding lead David to being ditched on the side of the road as an act of “mercy.”

From there, the movie becomes much more episodic with David and less interesting. The Gigolo Joe (Jude Law) addition furthers the story in a thematic sense and less so in plot. Gigolo Joe is a robotic lover on command, and framed for murder, and just as disposable and mistreated as David. From a plot standpoint, David’s odyssey is to seek out the Blue Fairy from Pinocchio, a book his mother read to him, and to wish to become a real boy and be finally accepted as his mother’s legitimate son. Thematically, David’s real odyssey is to understand that human beings are cruel masters. In short, people suck in this universe and they don’t get any better.

People, or “orga” as they refer to organic life, are mean and indifferent to artificial life, viewing the realistic mechanical beings, or “mecha” as they are referred to, as little more than disposable toys. Despite its cheery happy ending (and I will definitely be getting to that), the movie is awash in Kubrick’s trademark pessimism. Early on, David is stabbed by another boy just to test his pain defense system. David is only spared destruction from the Flesh Fair, a traveling circus where ticket-buyers enjoy the spectacle of robot torture, because the blood-thirsty audience thinks he’s too uncomfortably realistic. I don’t know if they’re supposed to be confused whether he is actually a robot considering that the adult models look just as realistic. He’s not like a super advanced model, he’s just the first robot kid, but applying the same torture spectacle to a crying robot child is too much for the fairgoers. However, this emergent reprieve might be short-lived once these same people become morally inured to the presence of robot kids after they flood the consumer market. Once the “newness” wears off, he’ll be viewed just as cruelly as the other older models also pleading for their pitiful mecha lives.

People, or “orga” as they refer to organic life, are mean and indifferent to artificial life, viewing the realistic mechanical beings, or “mecha” as they are referred to, as little more than disposable toys. Despite its cheery happy ending (and I will definitely be getting to that), the movie is awash in Kubrick’s trademark pessimism. Early on, David is stabbed by another boy just to test his pain defense system. David is only spared destruction from the Flesh Fair, a traveling circus where ticket-buyers enjoy the spectacle of robot torture, because the blood-thirsty audience thinks he’s too uncomfortably realistic. I don’t know if they’re supposed to be confused whether he is actually a robot considering that the adult models look just as realistic. He’s not like a super advanced model, he’s just the first robot kid, but applying the same torture spectacle to a crying robot child is too much for the fairgoers. However, this emergent reprieve might be short-lived once these same people become morally inured to the presence of robot kids after they flood the consumer market. Once the “newness” wears off, he’ll be viewed just as cruelly as the other older models also pleading for their pitiful mecha lives.

The tragedy of David is that he can never truly be real but he’ll never realize it. His personal journey takes him all over the nation and into the depth of the rising oceans, and it’s all to fulfill a wish from a benevolent make-believe surrogate mother. His programming traps David into seeing the world as a child, so no matter how old his circuits might be, he’ll always maintain a childish view of the world and its inhabitants. He’ll never age physically but he’ll also never mature or grow emotionally. Because of those limitations, he’s stuck seeing his mother in a halo of goodness that the actual woman doesn’t deserve. Monica felt like she was being helpful by ditching David before returning him to his makers, but this boy is not equipped to survive in the adult world let alone the human world. He cannot understand people and relationships outside the limited confines of a child. So to David, he doesn’t see the cowardice and emotional withdrawal of his mother. She knew the consequences of imprinting but she wanted to feel the unconditional love of a child again and when that got too inconvenient she abandoned him. Their relationship is completely one-sided with David always giving and his mother only taking. David’s goal is to be accepted by a woman who will never accept him and care for him like her organic child. She will never view David as hers no matter how hard David loves her. He cannot recognize this toxic usury relationship because he’ll never have any conception of that. David is trying to be loved by people undeserving of his earnest efforts and unflinching affections.

Let’s finally tackle that controversial ending, shall we? The natural ending comes at about two hours in, with David in a submersible at the bottom of the ocean and pleading with a statue of the Blue Fairy in Coney Island to make him a real boy. He keeps whispering again and again to her, and the camera pulls out, his pleading getting fainter and fainter. The vessel is trapped under the water, so he’ll likely live out the rest of his battery life hopefully, and hopelessly, asking for his wish. It feels deeply Kubrickian and a fitting end for a tragic and unsparing movie about human cruelty and our lack of empathy. It’s also, in its own way, slightly optimistic. Because David is so fixated, he’ll spend the rest of his existence in anticipation of his dream possibly being granted with the next request. He has no real concept of time so hundreds of years can feel like seconds. Everything about this moment screams the natural ending, and then, oh and then, it keeps going, and the ensuring twenty additional minutes try and force a sentimental ending that does not work or fit with the two hours of movie prior. Two thousand years into the future, David is rescued by advanced robots (I thought they were aliens, and likely you will too) who finally grant his wish thanks to some convenient DNA of his two-thousand-year dead mother. These advanced robots can bring the dead back to life except they will only last one day, so David will have one last day to share with his mother before she passes back into the dark. However, David’s conception of his mother isn’t the actual woman, so his rose-colored glasses distortion means he gets a final goodbye from not just a clone but one attuned to his vision. It’s false, and the fact that the movie tries to convince you it’s a happy ending feels wrong. Also, the world of 4124 still has the World Trade Center because A.I. was released three months before the attacks on September 11th. It’s just another reminder of how wrong the epilogue feels.

This extended epilogue desperately tries to attach the treacly sentimentality that was absent from the rest of A.I., which is why many critics felt it was Spielberg asserting himself. Apparently, we were all wrong. According to an interview with Variety in 2002, the opening 45 minutes is taken word-for-word from Kubrick’s outline and the extended ending, including the misplaced happy every after, is also strictly from Kubrick’s original treatment. It was Kubrick who went all-in on the Pinocchio references and parallels. Even the walking teddy bear was his idea. Watson said, “Those scenes were exactly what I wrote for Stanley and exactly what he wanted, filmed faithfully by Spielberg.” The middle portion was Spielberg’s greatest writing contribution, otherwise known as the darkest moments in the movie like the Flesh Fair and robot hunts. The movie is much more sexual than I associate with Spielberg. There has been sex in Spielberg’s past films, but it’s usually played as frothy fun desire with cheeky womanizers (Catch Me If You Can) or as a transaction with unspoken demands (Schindler’s List, The Color Purple). Then again, when Spielberg really leaned into a sex scene, we got the awkward and thematically clunky “climax” of Munich. With A.I., the perverse nature of humanity is another layer that reflects how awful these people are to the wide array or robots being mistreated, abused, and assaulted on an hourly basis in perpetuity.

Twenty years later, the movie still relatively holds up well and is good, not great. It’s more a fascinating collaboration between two cinematic giants, and the fun is recognizing the different elements and themes and attributing them (wrongly) to their respective creator. The special effects are still impressive and lifelike even by 2021 standards. Even though the movie is set in 2124, so over 100 years into the far-flung future, everyone still dresses and looks like they’re from the familiar twentieth century (maybe it’s retro fashion?). It’s a slightly distracting technical element for a movie otherwise supremely polished. There is a heavy emphasis on visual reflections and refractions of David in his family home, exploring the wavering identity and conceptions of this robo kid. Spielberg’s direction feels in keeping with Kubrick’s personal style and sensibility. A.I. is a labor of love for Spielberg to honor Kubrick, and he went another step further with the 2018 adaptation of Ready Player One where one of the missions was exploring a virtual reality recreation of the famous Overlook Hotel from The Shining. In my original 2001 review, I took the same level of umbrage with the miscalculated ending as I do in 2021. In the many years since its release, A.I. has been my go-to example of a movie that didn’t know where to properly end. As a result, it’s still a fascinating if frustrating experience on the verge of greatness.

Twenty years later, the movie still relatively holds up well and is good, not great. It’s more a fascinating collaboration between two cinematic giants, and the fun is recognizing the different elements and themes and attributing them (wrongly) to their respective creator. The special effects are still impressive and lifelike even by 2021 standards. Even though the movie is set in 2124, so over 100 years into the far-flung future, everyone still dresses and looks like they’re from the familiar twentieth century (maybe it’s retro fashion?). It’s a slightly distracting technical element for a movie otherwise supremely polished. There is a heavy emphasis on visual reflections and refractions of David in his family home, exploring the wavering identity and conceptions of this robo kid. Spielberg’s direction feels in keeping with Kubrick’s personal style and sensibility. A.I. is a labor of love for Spielberg to honor Kubrick, and he went another step further with the 2018 adaptation of Ready Player One where one of the missions was exploring a virtual reality recreation of the famous Overlook Hotel from The Shining. In my original 2001 review, I took the same level of umbrage with the miscalculated ending as I do in 2021. In the many years since its release, A.I. has been my go-to example of a movie that didn’t know where to properly end. As a result, it’s still a fascinating if frustrating experience on the verge of greatness.

Re-View Grade: B

The Post (2017)

Even with the added timely benefit of championing a free press in the era of Trump, Steven Spielberg’s The Post is a movie held together by big speeches and Meryl Streep. It’s the story of the Pentagon Papers but it’s told from the wrong perspective. It’s told through the reference of whether the owner of the Washington Post (Streep) will or will not publish and how this endangers her family’s financial control over the newspaper. Plenty of dismissive men doubt her because she’s a woman. It’s simply one of the least interesting versions of an important story. Streep is her standard excellent self and has a few standout moments where you can actively see her character thinking. I just don’t understand why all these talented people put so much effort into telling this version of this story. I missed the active investigation of Spotlight, how one piece lead to another and the bigger picture emerged. There was an urgency there that is strangely lacking with The Post. The question of whether she will publish is already answered. It feels like the screenplay is designed for Big Important Speeches from Important People. Tom Hanks plays the gruff editor of the newspaper and Streep’s chief scene partner. They’re enjoyable to watch, as is the large collection of great supporting actors (Bradley Whitford, Carrie Coon, Sarah Paulson, Tracy Letts, Matthew Rhys, Jesse Plemons, Bruce Greenwood, and a Mr. Show reunion with David Cross and Bob Odenkirk). This is a movie that is easier to admire than like, but I don’t even know if I admire it that much. The film has to call attention to Streep’s big decision and the stakes involved by underlining just what she has to lose and reminding you how brave she’s being. When Streep leaves the U.S. Supreme Court, there’s a bevy of supportive women lined up to bask in her accomplishment. It’s a bit much and another reminder that The Post doesn’t think you’ll understand its major themes. It’s a perfectly acceptable Oscar-bait drama but it sells its subject short and its audience.

Even with the added timely benefit of championing a free press in the era of Trump, Steven Spielberg’s The Post is a movie held together by big speeches and Meryl Streep. It’s the story of the Pentagon Papers but it’s told from the wrong perspective. It’s told through the reference of whether the owner of the Washington Post (Streep) will or will not publish and how this endangers her family’s financial control over the newspaper. Plenty of dismissive men doubt her because she’s a woman. It’s simply one of the least interesting versions of an important story. Streep is her standard excellent self and has a few standout moments where you can actively see her character thinking. I just don’t understand why all these talented people put so much effort into telling this version of this story. I missed the active investigation of Spotlight, how one piece lead to another and the bigger picture emerged. There was an urgency there that is strangely lacking with The Post. The question of whether she will publish is already answered. It feels like the screenplay is designed for Big Important Speeches from Important People. Tom Hanks plays the gruff editor of the newspaper and Streep’s chief scene partner. They’re enjoyable to watch, as is the large collection of great supporting actors (Bradley Whitford, Carrie Coon, Sarah Paulson, Tracy Letts, Matthew Rhys, Jesse Plemons, Bruce Greenwood, and a Mr. Show reunion with David Cross and Bob Odenkirk). This is a movie that is easier to admire than like, but I don’t even know if I admire it that much. The film has to call attention to Streep’s big decision and the stakes involved by underlining just what she has to lose and reminding you how brave she’s being. When Streep leaves the U.S. Supreme Court, there’s a bevy of supportive women lined up to bask in her accomplishment. It’s a bit much and another reminder that The Post doesn’t think you’ll understand its major themes. It’s a perfectly acceptable Oscar-bait drama but it sells its subject short and its audience.

Nate’s Grade: B

The BFG (2016)

Roald Dahl is the kind of highly imaginative, inventive, and subversive children’s author that makes one wonder why more of his books don’t end up as movies. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is the best known, and there’s Fantastic Mr. Fox, Matilda, James and the Giant Peach, and the rather spooky for kids 90s film, The Witches (it at least spooked me as a kid). For such a prolific author, it’s a little curious he has so few film credits. Steven Spielberg is one of the most successful directors of the modern era, so if anyone could wrangle Dahl’s wondrous worlds onto the big screen, he should. The BFG should be a transporting experience brought to vivid life with cutting-edge technology. All the special effects in the world, however, can’t solve a raft of nagging script problems that manage to take the fantastic and make it boring and predictable.

Roald Dahl is the kind of highly imaginative, inventive, and subversive children’s author that makes one wonder why more of his books don’t end up as movies. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is the best known, and there’s Fantastic Mr. Fox, Matilda, James and the Giant Peach, and the rather spooky for kids 90s film, The Witches (it at least spooked me as a kid). For such a prolific author, it’s a little curious he has so few film credits. Steven Spielberg is one of the most successful directors of the modern era, so if anyone could wrangle Dahl’s wondrous worlds onto the big screen, he should. The BFG should be a transporting experience brought to vivid life with cutting-edge technology. All the special effects in the world, however, can’t solve a raft of nagging script problems that manage to take the fantastic and make it boring and predictable.

In 1980s London, little orphan Sophie (newcomer Ruby Barnhill) is abducted one night when she spots a giant blowing a mysterious trumpet into the windows of sleeping children. Fortunately for Sophie her captor is the BFG (Mark Rylance), which stands for Big Friendly giant, and he’s a vegetarian, having sworn off the bone-eating habits of his nastier giant peers. In Giant Country, the BFG collects and cultivates dream particles, concocting special mixtures that he then shares with sleeping children. The other giants bully and snidely dismiss the puny BFG. Sophie and the kindly BFG must work together to stop the larger giants from going back to London and dining on innocent children.

The BFG has some pretty big friendly problems when it comes to its misshapen plot structure and its alarming lack of urgency or escalation. We’re all familiar, consciously or unconsciously, to the three-act story structure at this point, which is the principle formula for screenwriting. The BFG gets started pretty quickly, abducting Sophie and taking her to the land of giants by around the 15-minute mark, and from there the movie seems to take a leisurely stroll. I can’t really tell you where the act breaks are because the movie just sort of luxuriates in the meandering interaction between the BFG and his human pupil. There’s the initial threat that the other cannibalistic giants will discover her and this threat pops up in a handful of set pieces where Sophie has to constantly find new hiding places. Unfortunately, this threat never really magnifies or changes. She might get caught, and then she doesn’t. She might get caught, and then she doesn’t. There’s a repetition to this threat with our antagonists at no point getting more threatening. This is and a lack of a narrative motor make the movie feel rudderless, plodding from one moment to the next without a larger sense of direction. And then the third act comes (spoilers), presumably, when Sophie and the BFG travel back to London to try and recruit the Queen of England’s (Penelope Wilton) help. This sequence includes an extended breakfast that it punctuated by the memorable climax of watching the Queen fart and her little corgies fly around the room powered by their flatulence. It has to be the climax because what follows certainly doesn’t follow. Within five minutes, the BFG leads the Brits back to the land of giants and they restrain and airlift all the other giants in shockingly easy fashion. It’s a victory that feels relatively hollow because of its ease. These giants were never much of a threat to begin with, which is why we spent more time deliberating over dream ingredients than a retreat from man-eating colossuses.

The BFG has some pretty big friendly problems when it comes to its misshapen plot structure and its alarming lack of urgency or escalation. We’re all familiar, consciously or unconsciously, to the three-act story structure at this point, which is the principle formula for screenwriting. The BFG gets started pretty quickly, abducting Sophie and taking her to the land of giants by around the 15-minute mark, and from there the movie seems to take a leisurely stroll. I can’t really tell you where the act breaks are because the movie just sort of luxuriates in the meandering interaction between the BFG and his human pupil. There’s the initial threat that the other cannibalistic giants will discover her and this threat pops up in a handful of set pieces where Sophie has to constantly find new hiding places. Unfortunately, this threat never really magnifies or changes. She might get caught, and then she doesn’t. She might get caught, and then she doesn’t. There’s a repetition to this threat with our antagonists at no point getting more threatening. This is and a lack of a narrative motor make the movie feel rudderless, plodding from one moment to the next without a larger sense of direction. And then the third act comes (spoilers), presumably, when Sophie and the BFG travel back to London to try and recruit the Queen of England’s (Penelope Wilton) help. This sequence includes an extended breakfast that it punctuated by the memorable climax of watching the Queen fart and her little corgies fly around the room powered by their flatulence. It has to be the climax because what follows certainly doesn’t follow. Within five minutes, the BFG leads the Brits back to the land of giants and they restrain and airlift all the other giants in shockingly easy fashion. It’s a victory that feels relatively hollow because of its ease. These giants were never much of a threat to begin with, which is why we spent more time deliberating over dream ingredients than a retreat from man-eating colossuses.

Another aspect of Dahl’s novel that falls flat on screen is his verbal gymnastics and witticisms. It just doesn’t work with actors repeating the words without the text in front of your eyes. Listening to the BFG talk for any extended period of time is like being stuck with a crazy person muttering to him or herself. I would estimate that at least 60% of the BFG’s dialogue is folksy malapropisms. It’s not endearing and grows rather tiresome, especially with the unshakable stagnation of the movie’s plot. And so we get scene after scene of a big CGI creature talking verbal nonsense. Are children going to be entertained by any of this? Are they going to be engaged with the giant’s gibberish or will they find it one more impenetrable aspect of a movie and a story that seems to keep the audience at length? I couldn’t engage with the movie because it never gave me a chance to invest in what was happening. The BFG is a gentle soul and shouldn’t be bullied by his giant brethren, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to automatically love him. I didn’t.

For a Spielberg movie this feels oddly absent his more charming and whimsical touches. There are scant moments where it feels like Spielberg is playing to his abilities in this fantasy motion capture world, like exploring the underwater land where the BFG gathers his dream ingredients, and in the narrow and messy escapes Sophie has not to be caught. It’s a shame that the creative highs of Spielberg in full imagination mode are too often absent the rest of the movie. He too feels like he’s coasting, allowing the technology and the fantasy setting to do the heavy lifting. The land of the giants is a bit too underwhelming as far as fantasy worlds go. It’s simply too recognizable except for slight peculiarities, like “snozcumbers.” It’s not an enchanting location and we’re not given enchanting characters, and with the little narrative momentum or escalating stakes. I experienced a lot more fun and whimsy from Spielberg’s other major mo-cap movie, the nearly forgotten 2011 Adventures of Tintin. The action sequences especially had such a lively sense of comic brio and imagination that was pure Spielberg. I get no such feeling from The BFG. If you told me that Robert Zemeckis had made this movie I wouldn’t have blinked. I don’t know if Spielberg was hoping to recapture that E.T. magic with screenwriter Melissa Mathison (who passed away in 2015) but this isn’t close.

For a Spielberg movie this feels oddly absent his more charming and whimsical touches. There are scant moments where it feels like Spielberg is playing to his abilities in this fantasy motion capture world, like exploring the underwater land where the BFG gathers his dream ingredients, and in the narrow and messy escapes Sophie has not to be caught. It’s a shame that the creative highs of Spielberg in full imagination mode are too often absent the rest of the movie. He too feels like he’s coasting, allowing the technology and the fantasy setting to do the heavy lifting. The land of the giants is a bit too underwhelming as far as fantasy worlds go. It’s simply too recognizable except for slight peculiarities, like “snozcumbers.” It’s not an enchanting location and we’re not given enchanting characters, and with the little narrative momentum or escalating stakes. I experienced a lot more fun and whimsy from Spielberg’s other major mo-cap movie, the nearly forgotten 2011 Adventures of Tintin. The action sequences especially had such a lively sense of comic brio and imagination that was pure Spielberg. I get no such feeling from The BFG. If you told me that Robert Zemeckis had made this movie I wouldn’t have blinked. I don’t know if Spielberg was hoping to recapture that E.T. magic with screenwriter Melissa Mathison (who passed away in 2015) but this isn’t close.

I will credit the special effects department for the amount of work put into Rylance’s BFG visage, which looks eerily like the Oscar-winning actor. The range of the facial expressions is another sign that mo-cap performances are just as legitimate as live action flesh-and-blood performances. I can admire the technical feats of the character while not exactly feeling that much enjoyment from that character. The interaction between the computer elements and the real-life elements could be better, most bothersome with little Sophie interacting with the giant’s giant personal things.

I was left wondering whom The BFG is supposed to appeal to. I think kids and adults will be bored by its slow pace and stagnant, minimal stakes, weird and unengaging characters and their annoyingly impenetrable speech habits, and the overall lack of charm and wonder. It’s saying something significant when the most mesmerizing part of a fantasy movie is watching the Queen of England, her dogs, and a room full of her royal servants violently fart green clouds of noxious gas. That was the one moment in my screening where the kids in the room seemed to be awake. Otherwise the BFG character must have calmly put them to sleep with his prattling gibberish. It’s not an insufferable movie and there are fleeting moments of entertainment, but they drift away like a memory of a dream. There just isn’t enough going on in this movie to justify its near two-hour running time. Not enough conflict, not enough world exploration, not enough character bonding, not enough whimsy, and not enough entertainment. It feels too lightweight to matter and too dull to enchant. The BFG could have used more farts. That would be a sign of life.

Nate’s Grade: C+

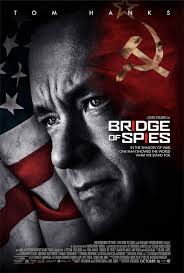

Bridge of Spies (2015)

An intriguing behind-the-scenes negotiation during a heightened period of danger, Bridge of Spies relies upon its history to do the heavy lifting and it’s plenty enough for a handsomely made, reverent, and engaging legal procedural that’s also hard to muster great passion over. Tom Hanks is again a noble everyman, this time an insurance lawyer, James Donovan, called in to defend a mild-mannered Russian spy (Mark Rylance) captured during the Cold War. Things get even more complicated when spy pilot Francis Powers is shot down over Soviet airspace. The movie’s civil liberties arguments are pretty clear and still applicable to our modern era, but the movie becomes exponentially more interesting once Powers is captured and Donovan travels to Eastern Berlin to negotiate a prisoner swap while trying to work three sides, the Americans, the Russians, and the Eastern Germans who were hungry for legitimacy. It’s during these back-and-forth negotiations and posturing that the movie really hits its stride, pulling incredible facts together while forcing our protagonist to be the world’s greatest poker player. It’s the details of this story that makes it feel more fulfilling from spy techniques to the new life on the other side of the Berlin Wall. The acting is robust and Rylance (TV’s Wolf Hall) makes a strong impression in a role that requires him to be cagey to a fault. Hanks is his usual determined, inspirational self, which plays all the right emotions in a way that still feels expected and a little boring. Bridge of Spies is a slighter Steven Spielberg affair, a good story well told with good actors but a movie missing essential elements to plant itself in your memory. It’s a fine movie but sometimes fine is just not enough, and considering the talent involved in front of and behind the camera, I expect better.

An intriguing behind-the-scenes negotiation during a heightened period of danger, Bridge of Spies relies upon its history to do the heavy lifting and it’s plenty enough for a handsomely made, reverent, and engaging legal procedural that’s also hard to muster great passion over. Tom Hanks is again a noble everyman, this time an insurance lawyer, James Donovan, called in to defend a mild-mannered Russian spy (Mark Rylance) captured during the Cold War. Things get even more complicated when spy pilot Francis Powers is shot down over Soviet airspace. The movie’s civil liberties arguments are pretty clear and still applicable to our modern era, but the movie becomes exponentially more interesting once Powers is captured and Donovan travels to Eastern Berlin to negotiate a prisoner swap while trying to work three sides, the Americans, the Russians, and the Eastern Germans who were hungry for legitimacy. It’s during these back-and-forth negotiations and posturing that the movie really hits its stride, pulling incredible facts together while forcing our protagonist to be the world’s greatest poker player. It’s the details of this story that makes it feel more fulfilling from spy techniques to the new life on the other side of the Berlin Wall. The acting is robust and Rylance (TV’s Wolf Hall) makes a strong impression in a role that requires him to be cagey to a fault. Hanks is his usual determined, inspirational self, which plays all the right emotions in a way that still feels expected and a little boring. Bridge of Spies is a slighter Steven Spielberg affair, a good story well told with good actors but a movie missing essential elements to plant itself in your memory. It’s a fine movie but sometimes fine is just not enough, and considering the talent involved in front of and behind the camera, I expect better.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Adventures of Tintin (2011)

It may not be fair, but I was never expecting to like Steven Spielberg’s first foray into animation, The Adventures of TinTin. It just looked so busy and I’m still on the fence when it comes to motion-capture technology. So imagine my surprise when I found myself not just enjoying the movie but also actively loving it. This rollicking adventure practically hums with energy and imagination. It’s easy to get lost in its sweep. The action sequences, of which there are several, are terrific, breathlessly paced but showing great fair and imagination. It comes to the closest of any imposter to replicating the magic of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Give great credit to Spielberg but also his team of terrific Brit writers (Dr. Who’s Steven Moffat, Edgar Wright, and the man behind Attack the Block, Joe Cornish). The characters don’t feel like soulless androids, the adventure is lively, the immersive visuals are gorgeous to behold, and the scale of some of these action set pieces is just massive, in particular a chase through a Moroccan city that is performed in one unblinking take (although does it matter when it’s animated?). I felt transported while watching Tintin, back to a time of childhood awe and excitement. Some will find the movie wearisome and vacant, but I’m prone to shaking off my adult quibbles when a movie can make me feel like a kid again

It may not be fair, but I was never expecting to like Steven Spielberg’s first foray into animation, The Adventures of TinTin. It just looked so busy and I’m still on the fence when it comes to motion-capture technology. So imagine my surprise when I found myself not just enjoying the movie but also actively loving it. This rollicking adventure practically hums with energy and imagination. It’s easy to get lost in its sweep. The action sequences, of which there are several, are terrific, breathlessly paced but showing great fair and imagination. It comes to the closest of any imposter to replicating the magic of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Give great credit to Spielberg but also his team of terrific Brit writers (Dr. Who’s Steven Moffat, Edgar Wright, and the man behind Attack the Block, Joe Cornish). The characters don’t feel like soulless androids, the adventure is lively, the immersive visuals are gorgeous to behold, and the scale of some of these action set pieces is just massive, in particular a chase through a Moroccan city that is performed in one unblinking take (although does it matter when it’s animated?). I felt transported while watching Tintin, back to a time of childhood awe and excitement. Some will find the movie wearisome and vacant, but I’m prone to shaking off my adult quibbles when a movie can make me feel like a kid again

Nate’s Grade: A-

Super 8 (2011)

Super 8 is writer/director J.J. Abrams’ reverent homage to early Spielberg movies. For some, it will be too reverent to the point of being a slobbery love letter.

Super 8 is writer/director J.J. Abrams’ reverent homage to early Spielberg movies. For some, it will be too reverent to the point of being a slobbery love letter.

In 1979, a small Ohio town, 13-year-old Joe Lamb (Joel Courtney) is reeling from the death of his mother in a factory accident. His father, Jackson (Kyle Chandler), is a police officer who doesn’t know how to raise his boy. He even tries to convince his son to spend the summer at a baseball camp. “It’ll be good for you to spend some time with kids who don’t run around with cameras and monster makeup,” he says. That kid is Charles (Riley Griffiths), a self-possessed amateur filmmaker. Charles is writing and directing a short Super 8 film and all his friends are helping. Joe’s specialty is makeup, given his attention to delicately painting models. Being the makeup guy comes in handy when the gang invites the local pretty girl, Alice (Elle Fanning), to be in their movie. Joe gets to apply her zombie makeup. One night, the gang sneaks out to a train yard to film a scene in their movie. A U.S. Air Force cargo train is passing by and suddenly derails, in grand apocalyptic fashion. Strange things start happening all over town shortly after the train crash. Car motors and electrical equipment go missing, dogs run away to neighboring communities, and people start to go missing. The Air Force comes into town and takes charge. It seems that train was carrying something and that something has escaped.

What Super 8 does best is replicate a time, place, and mood. The movie is successfully awash in nostalgia, and that childhood nostalgia is the best aspect of an otherwise ordinary film. Abrams has fashioned the greatest film tribute to Spielberg in history. But its limited ambition makes it feel like the greatest cover band of all time. You’ve assembled al your talent and energy into replicating someone else’s original work. Congratulations, Super 8 is a glossy tribute to Spielberg. Now what? Well, the movie works well at finding that unique, infectious spirit of being young and full of ideas. Filmmaking, and movies in general, has a magic to it, the synergistic creativity and the sheer possibilities that can abound. Translating the imagination into a communal artistic experience. I’m sure Abrams was just as excited about the possibilities of a camera in his childhood as Spielberg was. That feeling of discovery, that rambunctious creativity, and the endearing clumsiness of amateur productions, it all rings completely true. I made silly movies with a camera and my friends when I was younger; my group of friends and I became known for our video projects in high school. So I could have readily watched an entire movie about kids and cameras and their artistic aspirations (as long as it was better than Son of Rambo). The highpoint of Super 8 for me was, surprisingly, the children’s short film “The Case” that plays over the closing credits. It’s funny and charming and sweetly affable. Finally seeing Charles’ finished film is the ultimate payoff.

Abrams as a director is quite capable of delivering big summer moments. He’s a genre specialist and a geek’s best friend. I’ve even compared his style to that of a young Spielberg in my review of 2006’s Mission: Impossible III. Abrams has a natural feel for putting his camera in the right placement. While Abrams can do exciting action with the best of them, crafting compelling screen compositions to ignite the senses, it’s the smaller touches that connect to his storytelling that impress me most. The very opening shot tells you so much and grabs you. It’s a slow zoom into a factory’s sign proclaiming how many days have gone by without an accident. A man takes down the number plates and the count drops from 750 to 1. There’s a small moment where alice imitates a zombie, cocking her head, lurching, going in to bite Joe. And you see her, in that moment, as Joe does: a lovely young woman who makes your heart melt. With the aid of Michael Giacchino’s very John Williams-esque score, you effectively feel Joe’s burgeoning young love. Then when we pull back there’s a trace of Alice’s red lipstick along Joe’s neck, indicating she made actual contact. It’s a small detail that makes you smile all over. It’s these small details that often play to plot or character that affirm for me that Abrams is a director of fantastic promise, a true Spielberg protégé. Now if Abrams could lay off his excessive use of lens flairs (though it’s not as prevalent as Star Trek; you could make a drinking game into every time there was a lens flair).

The young actors are pretty good despite the somewhat hollow characterization by Abrams. These kids are defined by one-note traits (the kid obsessed with explosives, the wuss, etc.). I was going to be more upset by this until I remembered that movies like The Goonies, deemed a nostalgic classic by my generation, also had flimsy, one-note characterization (the fat kid is fat, the Asian kid has funny gadgets!). The scenes where all the kids are assembled make for some of the best entertainment. The young actors have a great rapport with one another and feel like a true makeshift band of friends. Their camaraderie, uncertainty, and hopes seem entirely genuine. They seem like real kids with real kid problems and worries. Courtney is a strong emotional center for the film. It’s hard to believe this is his first role on the big screen. Fanning (Somewhere, Curious Case of Benjamin Button) has been acting ever since she was the two-year-old version of her famous big sister in I Am Sam. I’m on the record as saying that Elle is a superior actress to her sister, and I feel like that claim bears fruit with Super 8. There’s a scene where Fanning’s character is asked to practice some feeble dialogue. Her cohorts think of her as a pretty girl and a source of transportation. But in this one scene, she turns on a dime, bringing out real emotions that leave the boys breathless and the audience too. It’s reminiscent of the audition scene in Mulholland Drive where Naomi Watts, at the flip of a switch, transformed into a different person, coursing with vibrant life. Consider it the toned-down kiddie version.

Truthfully, the monster stuff is actually the weakest part of the film. Super 8 works best as an endearing, nostalgic trip about being young. It works best as a coming-of-age tale and a somewhat touching first romance between teenagers. It does not work well as a sci-fi monster movie. You can tell that the monster/alien stuff has been grafted on to a separate storyline; the plots have little to no bearing on one another. If the kids happened to never go to that train stop that one night, their storyline would be almost entirely unaffected. It’s like parallel movies that pass each other occasionally but have little shared resonance. I found the human stuff, about being young and hurt and with your friends, to be affecting and interesting. The big-budget explosions, the monster mystery teased far too long, the subterranean third act that ends in a gob smack of logic issues, the heavy-handed metaphor about “letting go” (after only fours months? I think you’re still allowed to be sad four months after your mom dies) – that stuff plays well in trailers, but it’s far less interesting. The monster/alien conspiracy fails to lead to anything ripe in the narrative; the Air Force antagonists are more furtively empty than menacing. They don’t seem to care so much about a group of kids filming around the crash site. They’re pretty ineffective antagonists. The monster is hidden for so long, the film builds to an expectation level that it could never meet. The creature design of the monster/alien looks exactly like a smaller version of the Cloverfield creature (also produced by Abrams). When Super 8 is a poorly mimicking other B-movies, trying to wring tears by the film’s somewhat forced ending, I kept thinking, “The Iron Giant did this much better.” I guess once again aliens or a supernatural encounter helps people heal their family strife, which is something M. Night Shyamalan has been selling for years. This is one monster movie that would have been infinitely better without its monster.

Truthfully, the monster stuff is actually the weakest part of the film. Super 8 works best as an endearing, nostalgic trip about being young. It works best as a coming-of-age tale and a somewhat touching first romance between teenagers. It does not work well as a sci-fi monster movie. You can tell that the monster/alien stuff has been grafted on to a separate storyline; the plots have little to no bearing on one another. If the kids happened to never go to that train stop that one night, their storyline would be almost entirely unaffected. It’s like parallel movies that pass each other occasionally but have little shared resonance. I found the human stuff, about being young and hurt and with your friends, to be affecting and interesting. The big-budget explosions, the monster mystery teased far too long, the subterranean third act that ends in a gob smack of logic issues, the heavy-handed metaphor about “letting go” (after only fours months? I think you’re still allowed to be sad four months after your mom dies) – that stuff plays well in trailers, but it’s far less interesting. The monster/alien conspiracy fails to lead to anything ripe in the narrative; the Air Force antagonists are more furtively empty than menacing. They don’t seem to care so much about a group of kids filming around the crash site. They’re pretty ineffective antagonists. The monster is hidden for so long, the film builds to an expectation level that it could never meet. The creature design of the monster/alien looks exactly like a smaller version of the Cloverfield creature (also produced by Abrams). When Super 8 is a poorly mimicking other B-movies, trying to wring tears by the film’s somewhat forced ending, I kept thinking, “The Iron Giant did this much better.” I guess once again aliens or a supernatural encounter helps people heal their family strife, which is something M. Night Shyamalan has been selling for years. This is one monster movie that would have been infinitely better without its monster.

Super 8 is obviously a personal film for Abrams, harking back to his boyhood days of monster movies, amateur filmmaking, and young love. This nostalgic time warp will likely succeed with many audience members. Nostalgia is a powerful narrative weapon. It taps into our warm memories of old. But nostalgia is easy to pattern. What’s difficult is creating a work of art that people will be nostalgic over a generation hence. Super 8 is not going to be an inspiration to a new generation of budding young filmmakers; it reconfirms the joy of monsters, movies, and creative possibility. But the elements don’t gel. The monster stuff feels tacked on to an affecting coming-of-age tale about a group of kids working together to make a movie. Rarely will the two plots really have much traction with one another. I think Super 8 would have been an even better movie had the “summer movie” elements been stripped. No monster. No sci-fi thrills. No military intervention. No train crash. Just kids, a camera, and the emotions of growing up.

Nate’s Grade: B

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

I lived in New Haven, Connecticut for a year while then-partner was earning her Master’s degree at Yale. We hated it. New Haven is a college town that doesn’t know it’s a college town, so everything closes at 10 PM, there are no student prices for anything, and the people there more or less sucked. We were happy to depart from the Nutmeg State. Then the week after we were going to leave was when Steven Spielberg, Harrison Ford, and the production team for Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull were coming to town. They were going to film a motorcycle chase along Chapel Street (where I walked to work every day) and all along the Yale campus. Finally, a reason to stay in New Haven presents itself and it has to happen after we escape. It’s not often one of the most anticipated movies comes to your doorstep.

I lived in New Haven, Connecticut for a year while then-partner was earning her Master’s degree at Yale. We hated it. New Haven is a college town that doesn’t know it’s a college town, so everything closes at 10 PM, there are no student prices for anything, and the people there more or less sucked. We were happy to depart from the Nutmeg State. Then the week after we were going to leave was when Steven Spielberg, Harrison Ford, and the production team for Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull were coming to town. They were going to film a motorcycle chase along Chapel Street (where I walked to work every day) and all along the Yale campus. Finally, a reason to stay in New Haven presents itself and it has to happen after we escape. It’s not often one of the most anticipated movies comes to your doorstep.

I could have been an extra in the motorcycle chase, which set in 1957, could have used a long-haired Beatnik type (played by yours truly) for an exaggerated reaction shot. I could have been sipping on an espresso and then Indiana Jones could have zoomed by on the bike snatching by hot beverage, leaving a long-haired Beatnik type (me again) to mug shamelessly for the camera. It would have worked. Alas, it was not to be, though it certainly would have made this ages-in-development sequel more enjoyable on my part.