Blog Archives

The Rip (2026)

Director Joe Carnahan (The A-Team, Narc) excels at machismo, and I mean that not as a detriment. He makes muscular action-thrillers, often about corrupted men coming to terms with their ruination. 2012’s The Grey is still one of the best movies I’ve ever seen released in January. Well here comes The Rip, also released in January, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck as combustible Miami cops who follow a tip to a cartel stash house that holds a cache of twenty million dollars. The cops are supposed to follow protocol, call it into their superiors, but with that kind of money, much more than what the tip reported, it’s hard to resist the life-altering implications of indulging in that kind of haul. I thought The Rip, named after the seizure of contraband, was going to be a modern-day Treasure of the Sierra Madre, where the power of greed is irresistible and leads to betrayals and murder among our characters. It does that, with each questionable decision going against protocol making us question who might be most susceptible and who might be heading for a collision. The movie, co-written by Carnahan, is strictly genre boilerplate. The characters are never more than archetypes, the dialogue is aggressively expository often reminding us of all the conflicts and characters on the periphery that haven’t been brought back yet, and the majority of the film is a contained thriller awaiting trouble at the stash house. And yet I was entertained from start to finish thanks to the cast and a simmering tension that Carnahan unleashes between his paranoid characters. There are some late plot turns that I don’t know if they’re actually clever, convoluted, or both. It’s the kind of thing that’s meant to excuse bizarre behavior that we’d have no reason to assume differently, so it feels a little bit like being jerked around. However, The Rip is a fairly fun way to blow through two hours built upon movie stars unleashing their swagger.

Nate’s Grade: B-

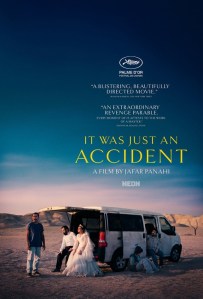

It Was Just an Accident (2025)

Iranian writer/director Jafar Panahi (The White Balloon, The Circle) is an example of an artist literally willing to put it all on the line for his art. He’s been banned by the authorities of Iran from making movies, and then Panahi secretly made a documentary of himself serving as a taxi driver in 2015. Scanning his filmography, all of his movies after 2000 were either made “illegally” or banned in his home country before their release. He was sentenced to a six-year prison sentence in 2022 and was released shortly after undergoing a hunger strike. Panahi filmed his latest movie, It Was Just an Accident, in secret without knowledge by the Iranian Authority, which makes sense considering how openly critical it is about the regime. It won the Palm D’or, the top prize, at the 2025 Cannes film festival and has been one of the most acclaimed movies of the year. It’s also likely going to make life much harder for Panahi, who was also sentenced in absentia by Iran to another prison sentence for “propaganda activities.” Yet his art persists, and It Was Just an Accident is easily one of the finest movies of 2025 and it’s no accident.

It begins simple enough. A middle-aged man and his family have car trouble after accidentally hitting a stray dog (sorry fellow animal lovers, but at least you don’t see it). They are taken into a nearby garage and that’s where the owner overhears the family man’s voice and then freezes in terror. He sounds EXACTLY like the man who interrogated and tortured him for the Iranian government years ago. Could it be the same man? How can he verify? And if so, what does he plan to do with his possible former captor?

What a brilliantly developed and executed movie this is, taking a concept that’s easy to plug right into no matter the language and cultural barriers, and then to unfold in such contemplative, bold, and unexpected ways. It captures mordant laughter, poignant human drama, and a nerve-wracking thrills. Most of all it’s terribly unexpected. As more and more people get brought in on the kidnapping, and more reveal their personal trauma from their shared captor, I really didn’t know what the fate would be for anyone. Would they kill this man? If so, what would that say and how would they view themselves after? If not, what lessons might they have learned from this ordeal and what lessons might their former captor have learned? It really kept me guessing and because it’s so exceptionally well developed and written, the script could have gone in any direction and I would have likely found satisfaction. There’s even the question over whether or not all these people are mistaken and projecting their fury onto an innocent man. However, I will say, the movie flirts with Coen-essque dark comedy, almost at a farcical level for its first half as these amateurs stumble their way through a kidnapping plot they are not equipped to control (a woman is stuck in her wedding dress for the entirety of these vigilante deliberations). Then in its second half it transitions into a really affecting moral drama about the lengths of trauma and the desire for forgiveness as a key point toward processing grief and preparing oneself to move forward. Even though the circumstances are specific to Iran, the movie is emblematic of accountability and reconciliation, and those elements can be easily empathized with no matter one’s cultural borders.

As you might expect, this is a movie brimming with anger, but it’s not suffused with bitterness, which is a remarkable feat given its subject matter. This is a movie that unfolds like a crime thriller, with each scene unlocking a better understanding of a hidden shared history. Each new character provides a larger sense of a bigger picture of oppressive state control and abuses, with each new person adding to the chorus of complaints. Naturally, many of these victims want to seek the harshest retribution possible for a man who tortured them with impunity. It’s easy to summon intense feelings of outrage and to demand vengeance. The filmmakers have other ideas in mind that aren’t quite as tidy. It’s easy to be consumed by anger, by outrage, that surging sense of righteous indignation filling you with vibrant purpose. It’s another matter to work through one’s anger rather than simply serve it. I’m reminded of the masterful 2021 movie Mass, a small indie about two groups of parents having a lengthy conversation; it just so happens one couple’s son was killed in a school shooting and the other couple’s son was the gunman responsible. It was a remarkably written movie (seriously, go watch it) and a remarkably empathetic movie for every character. It’s easy to pick sides of right and wrong, but it’s so much more engaging, intriguing, but also humane to find the foundations of connections, that every person lives with their own regrets and guilt and doubts. It Was Just an Accident follows a similar moral edict. Every character is a person, and every person is deserving of having their perspective better known, and we are better having given them this grace.

I think the movie is also especially prescient about this time and place in American history. It very well may prove a sign of the future, detailing a populace of the abused and traumatized and the former aggressors who worked for an authoritarian agent and administered cruel violence to cruel ends. It’s not difficult to see a version of this movie set in, say, 2035 America, with a ragtag group of characters discovering a retired ICE agent who they all have an antagonistic relationship with. In many ways the movie is about Iran and its history of an oppressive government turning on its own people, but in many ways it can also be about any system of power abusing that power to inflict fear and repudiation. It’s about a reckoning, and that’s why I think while the movie is clearly of its culture and time it’s very easy to apply the movie’s lessons and themes and larger ideas to any country, It’s all about characters coming to terms with harm and accountability, and sometimes it takes a long time after the fact for the perpetrators to accept that harm has been done, especially if they can fall on the morally indefensible “just following orders” defense. In the near future, will ICE agents, especially the ones who joined up after Trump took office for the second time, argue the same as the Nazis at Nuremberg? Will they rationalize their actions as just fulfilling a job to pay a mortgage? It might even be overly optimistic to believe a reckoning would even occur in the not-so-distant future, not to the profile of the Nuremberg trials but even just an individual accounting of individual wrongdoing. That assumes an acceptance of wrong and ostensibly a sincere request for forgiveness. As I write this, with an ICE officer whisked away to the protective bosom of federal government after executing a woman shortly after dropping her child off at school, it’s difficult for me to even accept that those in power and so eager to impose their bottomless grievances upon the vulnerable and innocent would ever allow themselves to accept the possibility of blame or regret. But then again this is perhaps what the citizens of Iran felt and they’re presently marching in the thousands to protest their authoritarian government in 2026, so maybe there’s hope yet for we Americans in 2026 too.

There is a deliberate sense to every minute of It Was Just an Accident, from its long takes to its interlocking sense of discovery, to the questions it raises, answers, and leaves for you to ponder. It’s a movie that drops you into a fully-realized world with rich characters that reveal themselves over time. If there’s one pressing moral for Panahi, I think it’s that every person matters, even the ones we’re told have less value. This is an insightful, searing, and ultimately compassionate cry for justice and empathy. It will be just as effective no matter the date you watch it, but with a movie this good, why wait?

Nate’s Grade: A

HIM (2025)

Setting a horror movie in the world of competitive sports, especially American football with its fandoms akin to dangerous cults of zealots, is a smart concept that could have so much possible commentary, from the sacrifices and exploitation of the players for the blood-lust of the fans, to the conspiracy of a cadre of white owners profiting from the labor of black athletes, to even the blinding psychopathy of extreme tribalism as an identity and dividing line. HIM does little to none of this, and being produced by Jordan Peele, I expected so much more than what I got. We follow a college phenom quarterback who wants to be the greatest, so he accepts an offer to train with a famous champion (Marlon Wayans) who puts him through a series of intense trials to prove whether he has what it takes. The horror elements are more confusing and surreal than unsettling, often crashing into unintentional comedy, like watching mascots with sledgehammers. This is one of those movies that seems to shift from scene to scene, with murky elements meant to keep the main character guessing but really just keeps the viewer guessing if this will ever come to something meaningful. The horror grew tiresome and repetitive. I was hoping for more scenes like where our young QB’s misses in practice lead to other players being physically abused, but mostly HIM hinges on tired occultly leftover furnishings, including an ending that is simultaneously underwhelming and predictable, a shrug meant as catharsis. An electrifying horror movie can certainly be made about the world of football. HIM isn’t it, let alone the possible GOAT.

Setting a horror movie in the world of competitive sports, especially American football with its fandoms akin to dangerous cults of zealots, is a smart concept that could have so much possible commentary, from the sacrifices and exploitation of the players for the blood-lust of the fans, to the conspiracy of a cadre of white owners profiting from the labor of black athletes, to even the blinding psychopathy of extreme tribalism as an identity and dividing line. HIM does little to none of this, and being produced by Jordan Peele, I expected so much more than what I got. We follow a college phenom quarterback who wants to be the greatest, so he accepts an offer to train with a famous champion (Marlon Wayans) who puts him through a series of intense trials to prove whether he has what it takes. The horror elements are more confusing and surreal than unsettling, often crashing into unintentional comedy, like watching mascots with sledgehammers. This is one of those movies that seems to shift from scene to scene, with murky elements meant to keep the main character guessing but really just keeps the viewer guessing if this will ever come to something meaningful. The horror grew tiresome and repetitive. I was hoping for more scenes like where our young QB’s misses in practice lead to other players being physically abused, but mostly HIM hinges on tired occultly leftover furnishings, including an ending that is simultaneously underwhelming and predictable, a shrug meant as catharsis. An electrifying horror movie can certainly be made about the world of football. HIM isn’t it, let alone the possible GOAT.

Nate’s Grade: D

No Other Choice (2025)

The title of the Korean movie No Other Choice is spoken, in English actually, a few minutes into the movie. It’s the brief, unhelpful reasoning from an American exec that just bought a South Korean paper company and is reducing the local labor force. Our main character, Yoo Man-su (Lee Byung-hun), has been work-shopping his spirited speech about how important these jobs are to appeal to the American businessmen, and then when it comes time to deliver, he’s reduced to chasing them down as they quickly depart. Before he can even get into a second poorly-formed sentence, the exec cuts him off by saying, “No other choice,” and then sidles into the protective safety of a chauffeured vehicle. The implication is that this business has to reduce its labor force to stay profitable, and yet rarely is this so simple. In legendary director Park Chan-wook’s (Old Boy, Decision to Leave) latest, characters will often repeat the title of the movie as a deference to guilt, that they were forced to make hard decisions because those were the only decisions that could be had. Unfortunately, as this mordantly funny, exciting, and intelligent movie proves, people have a way of deluding themselves when it comes to finding justifications for their bad behavior and greed.

The title of the Korean movie No Other Choice is spoken, in English actually, a few minutes into the movie. It’s the brief, unhelpful reasoning from an American exec that just bought a South Korean paper company and is reducing the local labor force. Our main character, Yoo Man-su (Lee Byung-hun), has been work-shopping his spirited speech about how important these jobs are to appeal to the American businessmen, and then when it comes time to deliver, he’s reduced to chasing them down as they quickly depart. Before he can even get into a second poorly-formed sentence, the exec cuts him off by saying, “No other choice,” and then sidles into the protective safety of a chauffeured vehicle. The implication is that this business has to reduce its labor force to stay profitable, and yet rarely is this so simple. In legendary director Park Chan-wook’s (Old Boy, Decision to Leave) latest, characters will often repeat the title of the movie as a deference to guilt, that they were forced to make hard decisions because those were the only decisions that could be had. Unfortunately, as this mordantly funny, exciting, and intelligent movie proves, people have a way of deluding themselves when it comes to finding justifications for their bad behavior and greed.

The real plot of No Other Choice is Man-su’s readjustment. In the beginning, we see the life he’s built for his family, his wife Lee Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), stepson Si-one, and daughter Ri-one, with their two big dogs. After a year of job searching, Man-su is bouncing from one job to another, and the family has been forced to make cutbacks to their lifestyle (“No Netflix?!” the son says in shock). Lee Mi-ri takes on a part-time job as a dental assistant to a hunky doctor. The dogs are shipped to Lee Mi-ri’s parents. Ri-one might have to stop her expensive cello lessons, which is a big deal as her teacher says the Autistic child is a prodigy, but her parents never hear her play. The paterfamilias needs to find a good job fast. That’s when Man-su gets the idea to post a fake job for a paper company manager to better scope out his competition. He takes the top applicants, the guys he acknowledges would be hired ahead of him, and creates a list. From there, Man-su pledges to track them down and eliminate them so his own odds of being rehired climb up.

The real plot of No Other Choice is Man-su’s readjustment. In the beginning, we see the life he’s built for his family, his wife Lee Mi-ri (Son Ye-jin), stepson Si-one, and daughter Ri-one, with their two big dogs. After a year of job searching, Man-su is bouncing from one job to another, and the family has been forced to make cutbacks to their lifestyle (“No Netflix?!” the son says in shock). Lee Mi-ri takes on a part-time job as a dental assistant to a hunky doctor. The dogs are shipped to Lee Mi-ri’s parents. Ri-one might have to stop her expensive cello lessons, which is a big deal as her teacher says the Autistic child is a prodigy, but her parents never hear her play. The paterfamilias needs to find a good job fast. That’s when Man-su gets the idea to post a fake job for a paper company manager to better scope out his competition. He takes the top applicants, the guys he acknowledges would be hired ahead of him, and creates a list. From there, Man-su pledges to track them down and eliminate them so his own odds of being rehired climb up.

The movie keeps shifting in new directions and tones with each new target, and it creates a much more fascinating and intriguing experience. I loved how each of the targeted rivals is treated differently and how each of these men come across as people who are struggling, hopeful, and quite like our beleaguered protagonist. There are good reasons why this movie has been described as Chan-wook’s Parasite, his culminating condemnation on the pitfalls of capitalism, how it pits peers against one another when they should be allies. Man-su views each man as his competition, impediments to him getting that prized position. However, each of these people is far more complicated than just their resume. At any time the movie could stop on a dime and just have two strangers, one of them intending to possibly kill the other, just have a heartfelt conversation about the difficulties of providing for your children and knowing that there are hard limitations that cannot be overcome. One man is struggling to adapt to a new marketplace after working in the paper industry for twenty years, and Man-su even echoes the complaints from the man’s wife, chiefly that he could have applied himself to other industries and jobs, that he didn’t have to be so discriminating when it came to a paycheck. Now, from her perspective, she’s arguing this point because she feels he is not casting a wider net for promising non-paper job opportunities. From Man-su’s perspective, he’s chiding the man because he doesn’t want to kill him but the guy’s intractability has put him in Man-su’s crosshairs. The unspoken comment is that Man-su is doing the same thing. At no point does he really consider getting a different job and thus being in a position where he does not feel forced to literally eliminate his best competition. He too is just as stubborn and blind to his own intractability. The system has a way of turning men against one another in order to boost a corporate balance sheet. This movie is just taking things a little further to the extreme when it comes to cutthroat competition.

I also appreciated that the movie has a larger canvas when it comes to charting the ups and downs of its conspiracy. Man-su’s wife is not kept as some afterthought, you know the kind of movie where the husband goes on these wild journeys of the soul and his wife is just as home going, “Where have you been?” She’s an active member of her household and she is not blind to their financial shortfalls nor her husband’s increasingly worrying behavior and absences. She’s worried her husband may have begun drinking again after years of sobriety and peace. She makes attempts to reconnect with her distant husband, who is becoming more consumed with jealousy about her boss and his desirability. She’s not just the doting spouse or concerned spouse. She’s a resourceful character who recognizes problems. When another threat to their family materializes, Lee Mi-ri takes it upon herself to find a solution. Naturally, given the premise, whenever you have one member of a couple doing dastardly deeds, whether they get caught by their partner is a primary point of tension, as well as if so, how will their partner respond. I think the track that Chan-wook and co-writers Lee Kyoung-mi, Don McKeller, and Le Ja-hye decide is perfect for the story that has been established and especially for the darker satirical tone of the enterprise.

I also appreciated that the movie has a larger canvas when it comes to charting the ups and downs of its conspiracy. Man-su’s wife is not kept as some afterthought, you know the kind of movie where the husband goes on these wild journeys of the soul and his wife is just as home going, “Where have you been?” She’s an active member of her household and she is not blind to their financial shortfalls nor her husband’s increasingly worrying behavior and absences. She’s worried her husband may have begun drinking again after years of sobriety and peace. She makes attempts to reconnect with her distant husband, who is becoming more consumed with jealousy about her boss and his desirability. She’s not just the doting spouse or concerned spouse. She’s a resourceful character who recognizes problems. When another threat to their family materializes, Lee Mi-ri takes it upon herself to find a solution. Naturally, given the premise, whenever you have one member of a couple doing dastardly deeds, whether they get caught by their partner is a primary point of tension, as well as if so, how will their partner respond. I think the track that Chan-wook and co-writers Lee Kyoung-mi, Don McKeller, and Le Ja-hye decide is perfect for the story that has been established and especially for the darker satirical tone of the enterprise.

Despite the murder and gnawing guilt, No Other Choice is also a very funny dark comedy as it channels the absurdity of its premise. It’s always a plus to have amateur murderers actually come across as awkward. Just because they decide to make that moral leap shouldn’t translate into them being good at killing. There’s unexpected humor to Man-su’s amateur stalking and preparations. He’s also not immune to the aftereffects of his actions, getting queasy with having to dispose of these men and thinking of the best ways to obscure his physical presence from crime scenes (there was one moment I was literally screaming at the screen because I thought he forgot a key detail). Lee Byung-hun (Squid Games) is terrific as our lead and finds such fascinating reactions as the movie effortlessly alters its style and tone, one minute asking him to engage in silly slapstick and the next heartfelt rumination. I don’t think the film would be nearly as successful without his sturdy performance serving as our foundation. You really do feel for him and his plight, and perhaps more than a few viewers might feel the urge for Man-su to get away with it. The culmination of the first target is a masterful sequence where three characters all have a different misunderstanding of one another as they literally wrestle for a gun inside an oven mitt. It’s one of those moments in movies where you can stop and think about all the small choices that got us here and appreciate the careful plotting from the screenwriters. I found myself guffawing at various points throughout the movie and I think many others will have the same wonderfully wicked reaction.

I could go on about the movie but hopefully I’ve done enough to convince you, dear reader, to give No Other Choice the ultimate decision for your potential entertainment. It’s a movie that covers plenty and leaves you deeply satisfied by its final minutes, feeling like you’ve just eaten a full meal. The ending is note-perfect, but then I could say just about every scene beforehand is also at that same artistic level. I won’t go so far as some of my critical brethren declaring this as Chan-wook’s best movie; I’ll always fall back on 2016’s The Handmaiden, also an adaptation of an English novel, much like No Other Choice (would you believe the source materiel is from the same author who gave us the novel for Play Dirty?). Regardless, this is exceptional filmmaking with a story that grabs you, surprises you, and glues you to the screen because you don’t know what may happen next (Patricia Highsmith would have loved this film).

I could go on about the movie but hopefully I’ve done enough to convince you, dear reader, to give No Other Choice the ultimate decision for your potential entertainment. It’s a movie that covers plenty and leaves you deeply satisfied by its final minutes, feeling like you’ve just eaten a full meal. The ending is note-perfect, but then I could say just about every scene beforehand is also at that same artistic level. I won’t go so far as some of my critical brethren declaring this as Chan-wook’s best movie; I’ll always fall back on 2016’s The Handmaiden, also an adaptation of an English novel, much like No Other Choice (would you believe the source materiel is from the same author who gave us the novel for Play Dirty?). Regardless, this is exceptional filmmaking with a story that grabs you, surprises you, and glues you to the screen because you don’t know what may happen next (Patricia Highsmith would have loved this film).

Nate’s Grade: A

The Secret Agent (2025)

The Secret Agent is a hard movie to fully categorize. It’s set in 1977 Brazil and with its title you might think it’s about some clandestine espionage operation or fighting against a corrupt government, and it does fit those descriptions but not in a traditional Hollywood way. We follow Wagner Moura (Narcos, Civil War) as a former grant-supported energy scientist who comes to clash with a powerful businessman who then hires an assassination team to kill this know-it-all. It’s also about entrenched police corruption and coverups, a found family of people seeking protection and new lives, the search for memory and proof of life, a father wanting to connect with his son in the wake of his mother’s death, and then there’s a running story about a severed leg that goes into the wildest, most unexpected places. It is a leisurely paced movie at almost two hours and forty minutes in length, but each scene is its own luxurious moment to dwell in. Take for instance the opening scene where Moura drives his car to a dusty, rural gas station and finds a dead body covered in newspaper. Nobody wants to come claim the corpse, and then the police do arrive but they take particular interest in Moura, wanting to search his car and ask him questions. Do they know something? Who is this man? A similar early scene involves the police investigating a dead shark where a severed human leg was found inside its mouth, and the way it unfolds and escalates is so naturally fascinating. The Secret Agent juggles many different tones, from nostalgic drama to crime thriller, but every scene is so expertly written and paced by writer/director Kleber Mendoca Filho (Aquarius, Pictures of Ghosts). You may grow weary by its length, but when I was in every scene, I didn’t want it to end because it feels so well-realized in its moment. There’s a subversive switch-out with its climax that reminded me of No Country for Old Men, and the ending coda ties together the flash-forwards and hits hard with the theme of uncovering and honoring the past. This is a lot of movie, much of it I admired more than I outright loved, but it’s such a fascinating balancing act that I would recommend The Secret Agent as a sprawling dive into Brazilian history, culture, and its own political reckoning.

The Secret Agent is a hard movie to fully categorize. It’s set in 1977 Brazil and with its title you might think it’s about some clandestine espionage operation or fighting against a corrupt government, and it does fit those descriptions but not in a traditional Hollywood way. We follow Wagner Moura (Narcos, Civil War) as a former grant-supported energy scientist who comes to clash with a powerful businessman who then hires an assassination team to kill this know-it-all. It’s also about entrenched police corruption and coverups, a found family of people seeking protection and new lives, the search for memory and proof of life, a father wanting to connect with his son in the wake of his mother’s death, and then there’s a running story about a severed leg that goes into the wildest, most unexpected places. It is a leisurely paced movie at almost two hours and forty minutes in length, but each scene is its own luxurious moment to dwell in. Take for instance the opening scene where Moura drives his car to a dusty, rural gas station and finds a dead body covered in newspaper. Nobody wants to come claim the corpse, and then the police do arrive but they take particular interest in Moura, wanting to search his car and ask him questions. Do they know something? Who is this man? A similar early scene involves the police investigating a dead shark where a severed human leg was found inside its mouth, and the way it unfolds and escalates is so naturally fascinating. The Secret Agent juggles many different tones, from nostalgic drama to crime thriller, but every scene is so expertly written and paced by writer/director Kleber Mendoca Filho (Aquarius, Pictures of Ghosts). You may grow weary by its length, but when I was in every scene, I didn’t want it to end because it feels so well-realized in its moment. There’s a subversive switch-out with its climax that reminded me of No Country for Old Men, and the ending coda ties together the flash-forwards and hits hard with the theme of uncovering and honoring the past. This is a lot of movie, much of it I admired more than I outright loved, but it’s such a fascinating balancing act that I would recommend The Secret Agent as a sprawling dive into Brazilian history, culture, and its own political reckoning.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Bugonia (2025)

A remake of a 2003 South Korean movie, Bugonia is an engaging conflict that needed further restructuring and smoothing out to maximize its entertainment potential. Jessie Plemons stars as a disturbed man beholden to conspiracy theories, namely that the Earth is populated with aliens among us that are plotting humanity’s doom. He kidnaps his corporate boss, a cold and cutthroat CEO (Emma Stone), who he is convinced is really an Andromedan and can connect him with the other aliens. The problem here is that the story can only go two routes. Either Plemons’ character is just a dangerous nutball and has convinced himself of his speculation and this will lead to tragic results, or his character will secretly be right despite the outlandish nature and specificity of his conspiracy claims. Once you accept that, it should become more clear which path offers a more memorable and interesting story. The appeal of this movie is the tense hostage negotiation where this woman has to wonder how to play different angles to seek her freedom from a deranged kidnapper. Both actors are at their best when they’re sparring with one another, but I think it was a mistake to establish so much of Plemons and his life before and during the kidnapping. I think the perspective would have been improved following Stone from the beginning and learning as she does, rather than balancing the two sides in preparation. The bleak tone is par for a Yorgos Lanthimos (Poor Things) movie but the attempts at humor, including some over-the-top gore as slapstick, feel more forced and teetering. I never found myself guffawing at any of the absurdity because it’s played more for menace. The offbeat reality that populates a Lanthimos universe is too constrained to the central characters, making the world feel less heightened and weird and therefore the characters are the outliers. I enjoyed portions of this movie, and Stone’s performance has so many layers in every scene, but Bugonia feels like an engaging premise that needed more development and focus to really get buggy.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Eddington (2025)

I’ve read more than a few searing indictments about writer/director Ari Aster’s latest film, Eddington, an alienating and self-indulgent movie starring Joaquin Phoenix on the heels of his last alienating and self-indulgent movie starring Phoenix. It’s ostensibly billed as a “COVID-era Western,” and that is true, but it’s much more than that. I can understand anyone’s general hesitation to revisit this acrimonious time, but that’s where the “too early yet too late” criticism of others doesn’t ring true for me. It is about that summer of 2020 and the confusion and anger and anxiety of the time; however, I view Eddington having more to say about our way of life in 2025 than looking back to COVID lockdowns and mask mandates. This is a movie about the way we live now and it’s justifiably upsetting because that’s where the larger culture appears to be at the present: fragmented, contentious, suspicious, and potentially irrevocable.

Eddington is a small-town in the dusty hills of New Mexico, neighboring a Pueblo reservation, and it serves as a tinderbox ready to explode from the tension exacerbated from COVID. Sheriff Joe Cross (Phoenix) has had it up to here with mask mandates and social distancing and the overall attitude of the town’s mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal). Joe decides to run for mayor himself on a platform of common-sense change, but nothing in the summer of 2020 was common.

Eddington is a movie with a lot of tones and a lot of ideas, and much like 2023’s Beau is Afraid, it’s all over the place with mixed results that don’t fully come together for a coherent thesis. However, that doesn’t deny the power to these indefatigable moments that stick with you long after. That’s an aspect of Aster movies: he finds a way to get under your skin, and while you may very well not appreciate the experience because it’s intentionally uncomfortable and probing, it sticks with you and forces you to continue thinking over its ideas and creative choices. It’s art that defiantly refuses to be forgotten. With that being said, one of the stronger aspects of Aster’s movies is his pitch-black sense of comedy that borders on sneering cynicism that can attach itself to everything and everyone. There are a lot of targets in this movie, notably conspiracy-minded individuals who want people to “do their own research,” albeit research ignoring verified and trained professionals with decades of experience and knowledge. There’s a lot of people talking at one another or past one another but not with one another; active listening is sorely missing, as routinely evidenced by the silences that accompany the mentally-ill homeless man in town that nobody wants to actively help because they see him as an uncomfortable and loud nuisance. For me, this is indicative of 2025, with people rapidly talking past one another rather than wanting to be heard.

When Aster is poking fun at the earnestness of the high school and college students protesting against police brutality, I don’t think he’s saying these younger adults are stupid for wanting social change. He’s ribbing how transparently these characters want to earn social cache for being outspoken. It’s what defines the character of Brian, just a normal kid who is so eager to be accepted that he lectures his white family on the tenets of destroying their own white-ness at the dinner table, to their decidedly unenthusiastic response. I don’t feel like Aster is saying these kids are phony or their message is misapplied or ridiculous or without merit. It’s just another example of people using fractious social and political issues as a launching point to air grievances rather than solutions. The protestors, mostly white, will work themselves into a furious verbal lather and then say, “This shouldn’t even be my platform to speak. I don’t deserve to tell you what to do,” and rather than undercutting the message, after a few chuckles, it came across to me like the desperation to connect and belong coming out. They all want to say the right combination of words to be admired, and Brian is still finding out what that might be, and his ultimate character arc proves that it wasn’t about ideological fidelity for him but opportunism. The very advancement of Brian by the end is itself its own indictment on white privilege, but you won’t have a character hyperventilating about it to underline the point. It’s just there for you to deliberate.

Along these lines, there’s a very curious inclusion of a trigger-happy group in the second half of the movie that blends conspiracy fantasy into skewed reality, and it begs further unpacking. I don’t honestly know what Aster is attempting to say, as it seems like such a bizarre inclusion that really upends our own understanding of the way the world works, and maybe that’s the real point. Maybe what Aster is going for is attempting to shake us out of our own comfortable understanding of the universe, to question the permeability of fact and fiction. Maybe we’re supposed to feel as dizzy and confused as the residents of Eddington trying to hold onto their bearings during this chaotic and significant summer of 2020.

I think there’s an interesting rejection of reality on display with Eddington, where characters are trying to square news and compartmentalize themselves from the proximity of this world. Joe Cross repeatedly dismisses the pandemic as something happening “out there.” He says there is no COVID in Eddington. For him, it’s someone else’s problem, which is why following prevailing health guidelines and mandates irks him so. It’s the same when he’s trying to explain his department’s response to the Black Lives Matter protests that summer in response to George Floyd’s heinous murder. To him, these kinds of things don’t happen here, the people of Eddington are excluded from the social upheaval. This is an extension of the “it won’t happen to me” denialism that can tempt any person into deluding ourselves into false security. It’s this kind of rationalization that also made a large-scale health response so burdensome because it asked every citizen to take up the charge regardless of their immediate danger for the benefit of others they will never see. For Joe, the tumult that is ensnaring the rest of the country is outside the walls of Eddington. It’s a recap on a screen and not his reality. Except it is his reality, and the movie becomes an indictment about pretending you are disconnected from larger society. It’s easier to throw up your hands and say, “Not me,” but it’s hard work to acknowledge the troubles of our times and our own engagement and responsibilities. In 2025, this seems even more relevant in our doom-scrolling era of Trump 2.0 where the Real World feels a little less real every ensuing day. It’s all too easy to create that same disassociation and say, “That’s not here,” but like an invisible airborne virus not beholden to boundaries and demarcations, it’s only a matter of time that it finds your doorstep too.

You may assume with its star-studded cast that this will be an ensemble with competing storylines, but it’s really Joe Cross as our lead from start to finish, with the other characters reflections of his stress. I won’t say that most of the name actors are wasted, like Emma Stone as Joe’s troubled wife and Austin Butler as a charismatic conman pushing repressed memory child-trafficking conspiracies, because every person is a reflection over what Joe Cross wants to be and is struggling over. Despite his flaws and some startling character turns, Aster has great empathy for his protagonist, a man holding onto his authority to provide a sense of connectivity he’s missing at home. Our first moment with this man is watching him listen to a YouTube self-help video on dealing with the grief of wanting children when your spouse does not. Right away, we already know there’s a hidden wealth of pain and disappointment here, but again Aster chooses empathy rather than easy villainy, as we learn his wife is struggling with PTSD and depression likely as a result of her own father’s potential molestation. This revelation can serve as a guide for the rest of the characters, that no matter their exterior selves that can demonstrate cruelty and absurdism, deep down many are processing a private pain that is playing out through different and often contentious means of survival. I don’t think Aster condones Joe Cross’ perspective nor his actions in the second half, but I do think he wants us to see Joe Cross as more than just some rube angry with lockdown because he’s selfish.

It’s paradoxical but there are scenes that work so splendidly while the movie as a whole can seem overburdened and far too long. The cinematography by the legendary Darius Khnodji (Seven, City of Lost Children) expertly frames and lights each moment, many of them surprising, intriguing, revealing, or shocking. There can be turns that feel sudden and jarring, that catapult the movie into a different genre entirely, into a Hitchcockian thriller where we know exactly what the reference point is that I won’t spoil, to an all-out action showdown popularized by Westerns. Beyond Aster’s general more-is-more preference, I think he’s dabbling with the different genres to not just goose his movie but to question our associations with those genres and our broader understanding of them. It’s not quite as clean as a straight deconstructionist take on familiar archetypes and tropes. It’s more deconstructing our feelings. Are we all of a sudden in a forgiving mood because the movie presents Joe as a one-man army against powerful forces? It’s all-too easy to get caught up in the rush of tension and satisfying violence and root for Joe, but should we? Is he a hero just because he’s out-manned? Likewise, with the conclusion, do we have pity for these people or contempt? I don’t know, though there isn’t much hope for the future of Eddington, and depressingly perhaps for the rest of us, so maybe all we have are those fleeting moments of awe to hold onto and call our own.

Eddington is an intriguing indictment about our modern culture and the rifts that have only grown into insurmountable chasms since the COVID-19 outbreak. It’s a Western in form pitting the figure of the law against the moneyed establishment, and especially its showdown-at-the-corral climax, but it’s also not. It’s a drama about people in pain looking for answers and connections but finding dead-ends, but it’s also not. It’s an absurdist dark comedy about dumb people making dumb and self-destructive decisions, but it’s also not. The paranoia of our age is leading to a silo-ing of information dissemination, where people are becoming incapable of even agreeing on present reality, where our elected leaders are drowning out the reality they don’t want voters to know with their preferred, self-serving fantasy, and if they just say it long enough, then a vulnerable populace will start to conflate fact and fiction. I don’t know what the solution here is, and I don’t think Aster knows either by the end of Eddington. I can completely understand people not wanting to experience a movie with these kinds of uncomfortable and relevant questions, but if you want to have a closer understanding of how exactly we got here, then Eddington is an artifact of our sad, stupid, and supremely contentious times. Don’t be like Joe and ignore what’s coming until it’s too late.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Black Phone 2 (2025)

The original 2022 Black Phone was a relatively entertaining contained thriller where a kid was relying upon the ghosts of victims to escape the clutches of an evil kidnapper. It had other elements to fill it out as a movie, like a psychic sister, but the central conceit and execution worked well, especially a disturbing performance by Ethan Hawke as The Grabber, the aforementioned grabber and locker-away-er of unfortunate children. Then it was popular enough to demand a sequel, but where do you go when the villain has been killed and the source material, a short story by Joe Hill, has been exhausted? The answer is to turn the very-human Grabber into a Freddy Krueger-style supernatural predator terrorizing our survivors in their dreams. The kids from the first film are now teenagers and really the psychic sis is the main character. She’s the one most affected by the Grabber’s supernatural vengeance. Most of the movie is watching the sister get tossed around invisibly in the real world and talking to irritable ghost kids. There’s a mystery about uncovering the truth about what happened to their deceased mother, who too could have a personal connection to the Grabber from a Christian summer camp located in the far mountains. The snowy locale makes for a visually distinctive setting, though once you see the Grabber ghost ice skating it does take a little of the mystique away from the overall menace. The Black Phone 2 just didn’t work for me, feeling like another “let’s help these dead kids be at peace” adventure like a weekly TV series, but the scenario just didn’t have the draw and satisfaction of the original. I suppose the returning filmmakers wanted to expand their universe and its mythology, Dream Children-style, but the material doesn’t seem there to build a franchise foundation. The first film was simple and complete (makes me think of a variation on a line at the end of Bioshock Infinite: “There’s always a Grabber. There’s always a black phone. There’s always a ghost”). The sequel cannot compensate for that, and so it feels overstretched, underdeveloped, and goofy. At least they tried something different than just a straight replica of the original but it would have been best to leave the Grabber and us at rest.

Nate’s Grade: C

The Long Walk (2025)

The quality of Stephen King adaptations may be the scariest legacy for publishing’s Master of Horror. The best-selling author has given us many modern horror classics but the good King movies are more a minority to what has become a graveyard of schlocky productions. Everyone has their own top-tier but I think most would agree that for such a prolific author, you can probably count on two hands the “good to great” King movies and have a few fingers to spare. 2025 is a bountiful year for King fans, with the critically-acclaimed The Life of Chuck, the remake of The Monkey, the upcoming remake of The Running Man, which was originally set in a nightmarish future world of… 2025, and now The Long Walk. Interestingly, two of these films are adaptations from King’s Richard Bauchman books, the pseudonym he adopted to release more novels without “diluting the King brand,” or whatever his publisher believed. The Long Walk exists in an alternative America where teen boys compete to see who can last the longest in a walking contest. If they drop below three miles per hour, they die. If they step off the paved path, they die. If they stop too often, they die. There is no finish line. The game continues until only one boy is left.

The Long Walk is juiced with tension. It’s like The Hunger Games on tour. (director Francis Lawrence has directed four Hunger Games movies) I was shocked at how emotional I got so early in the movie, and that’s a testament to the stirring concept and the development that wrings the most dread and anxiety from each moment. Just watching a teary-eyed Judy Greer say a very likely final goodbye to her teenage son Ray (Cooper Hoffman), contemplating what those final words might be if he never returns to her, which is statistically unlikely since he’s one of 50 competitors. How do you comprise a lifetime of feeling, hope, and love into a scant few seconds? It’s an emotionally fraught opening that only paves the way for a consistently emotionally fraught journey. In essence, you’re going along on this ride knowing that 49 of these boys are going to be killed over the course of two hours, and yet when the first execution actually takes place, it is jarring and horrifying. The violence is painful. From there, we know the cruel fate that awaits any boy that cannot follow the limited rules of the contest. The first dozen or so executions are given brutish violent showcases, but as the film progresses and we become more attached to the ever-dwindling number of walkers, the majority of the final executions happen in the distance, out of focus, but are just as hard-hitting because of the investment. Every time someone drops, your mind soon pivots to who will be next, and if you’re like me, there’s a heartbreak that goes with each loss. From there, it becomes a series of goodbyes, and it’s much like that super-charged opening between mother and son. Each person dropping out becomes another chance to try and summarize a lifetime, to communicate their worth in a society that literally sees them as disposable marketing tools. I was genuinely moved at many points, especially as Ray takes it upon himself to let the guys know they had friends, they will be remembered, and that they too mattered. I had tears in my eyes at several points. The Long Walk is a grueling experience but it has defiant glimmers of humanity to challenge the prevailing darkness.

I appreciated that thought has been taken to deal with the natural questions that would arise from an all-day all-night walkathon. What happens when you have to poop? What happens when you have to sleep? The screenplay finds little concise examples of different walkers having to deal with these different plights (it seems especially undignified for so many to be killed as a result of uncontrollable defecation). There’s a late-night jaunt with a steep incline, which feels like a nasty trap considering how sleep-deprived many will be to keep the minimal speed requirement. That’s an organic complication related to specific geography. It’s moments like this that prove how much thought was given to making this premise as well-developed as possible, really thinking through different complications. I’m surprised more boys don’t drop dead from sheer exhaustion walking over 300 miles without rest over multiple days. I am surprised though that after they drop rules about leaving the pavement equals disqualification and death that this doesn’t really arise. I was envisioning some angry walker shoving another boy off the path to sabotage him and get him eliminated. This kind of duplicitous betrayal never actually happens.

There’s certainly room for larger social commentary on the outskirts of this alternative world. King wrote the short story as a response to what he felt was the senseless slaughter of the Vietnam War. In this quasi-1970s America, a fascist government has determined that its workforce is just too lazy, and so the Long Walk contest is meant as an inspiration to the labor to work harder. I suppose the argument is that if these young boys can go day and night while walking with the omnipresent threat of death, then I guess you can work your factory shift and stop complaining, you commie scum. The solution of more dead young men will solve what ails the country can clearly still resonate even though we’re now four decades removed from the generational mistakes of the Vietnam War. The senselessness of the brutality is the point, meant to confront a populace growing weary with The Way Things Are, and as such, it’s a malleable condemnation on any authority that looks to operate by fear and brutality to keep their people compliant. There are some passing moments of commentary, like when the occasional onlooker is sitting and watching the walkers, drawing the ire of Ray who considers these rubberneckers to a public execution. They’re here for the blood, for the sacrifices, for the thrill. It’s risible but the movie doesn’t really explore this mentality except for some glancing shots and as a tool to reveal different perspectives.

Let’s talk about those leads because that’s really the heart of the movie, the growing friendship and even love between Ray and Pete (David Jonsson). They attach themselves early to one another and form a real sense of brotherhood, even dubbing each other the brother they’ve never had before. They’re the best realized characters in the movie and each has competing reasons for wanting to win. For Ray, it’s about a sense of misplaced righteousness and vengeance. For Pete, it’s about trying to do something better with society. His whole philosophy is about finding the light in the darkness but he is very clear how hard living this out can be on a daily basis. It’s a conscious choice that requires work but a bleak universe needs its points of light. Of course, as these gents grow closer to one another, saving each other at different points, the realization sets in that only one of these guys is going to make it across the proverbial finish line. We’re going to have to say goodbye to one of them, and that adds such a potent melancholy to their growing friendship, that it’s a relationship destined to be meaningful but transitional, a mere moment but a lifetime condensed into that moment. It’s easy to make the connection between this shared camaraderie built from overwhelming danger to soldiers being willing to die for their brothers in arms. Hoffman (Licorice Pizza) and Jonsson (Alien: Romulus) are both so immediately compelling, rounding out their characters, so much so that the whole movie could have been a 90-minute Richard Linklater-style unbroken conversation between the great actors and I would’ve been content.

My one reservation concerns the ending and, naturally, in order to discuss this I’ll be dealing with significant spoilers. If you wish to remain pure, dear reader, skip to the final paragraph ahead. It should be no real surprise who our final two contestants are because the filmmakers want us to really agonize over which of these two men will die for the other. Since we begin with Ray being dropped off, we’re already assuming he’s going to be the eventual winner. He’s got the motivation to seek vengeance against the evil Major who killed his father for sedition by educating Ray about banned art. He’s also been elevated to our lead. Even Pete has a monologue criticizing his friend for ever getting involved when he still has family. Pete has no family left and he has ideals to change the system. The screenplay seems to be setting us up for Pete being a change agent that forces Ray to recognize his initial winning wish of vengeance is selfish and myopic for all the bad out there in this warped society. It seems like Pete is being set up to influence Ray to think of the big picture and perhaps enact meaningful change with his winning wish. There’s even a couple of moments in the movie Pete directly saves Ray, going so far as to purposely kneel to allow Ray the opportunity to win. There’s also the Hollywood meta-textual familiarity of the noble black character serving as guide for the white lead to undergo meaningful change. It all feels thoroughly fated.

Then in a surprise, Ray pulls the same stunt and purposely stops so his buddy can win by default. As Ray dies, he admits that he thinks Pete was the best equipped to bring about that new world they were talking about. He dies sacrificing his own vengeance for something larger and more relevant to the masses. And then Pete, as per his winning wish, asks for a rifle, shoots and kills the Major, thus fulfilling Ray’s vendetta, and walks off. The end. The theme of thinking about something beyond personal grievance to help the masses, to enact possible change, is thrown away. So what was it all about? The carnage continues? It seems like thematic malpractice to me that the movie is setting up its two main characters at philosophical odds, with one preaching the value of forgoing selfish wish-fulfillment for actual change. The character arc of Ray is about coming to terms not just with the inevitability of his death but the acceptance of it because he knows that Pete will be the best person to see a better world. The fact that Pete immediately seeks bloody retribution feels out of character. The Long Walk didn’t feel like a story about a guy learning the opposite lesson, that he should be more selfish and myopic. It mitigates the value of the sacrifice if this is all there is. Furthermore, it’s strange that the bylaws of this whole contest allow a winner to murder one of the high-ranking government officials. Even The Purge had rules against government officials and emergency medical technicians being targeted (not that people followed those rules to the letter). Still, it calls into question the reality of this deadly contest and its open-ended rewards. If a winner demanded to go to Mars, would the nation be indebted to see this through no matter the cost? Suddenly contestant wishes like “sleep with ten women” seem not just banal but a derelict of imagination.

Affecting and routinely nerve-racking, The Long Walk is an intense and intensely felt movie. I was overwhelmed by tension at different points as well as being moved to tears at other points. While its dystopian world-building might be hazy, the human drama at its center is rife with spirit and life, allowing the audience to effortlessly attach themselves to these characters and their suffering. I feel strongly that the very end is a misstep that jettisons pertinent themes the rest of the movie had been building, but it’s not enough to jettison the power and poignancy of what transpires before that climactic moment. The Long Walk has earned its rightful place in the top-tier of Stephen King adaptations.

Nate’s Grade: B+

A House of Dynamite (2025)

Director Kathryn Bigelow’s first movie in eight years plays to her strengths with a dynamite ensemble cast trying to process a ticking clock of doom and their dwindling options. It’s an incredibly taut and thrilling movie elevated by Bigelow’s penchant for later-career verisimilitude. A nuclear missile is launched from an Asian country (North Korea? Russia? It’s never clarified) and heading for the American Midwest. The movie replays the chain of events three times and in real-time, first with the initial discovery of the missile and those in charge of launching counter defenses to take it out (a character describes the difficulty as “shooting a bullet with a bullet”). Then with the higher military brass debating whether to launch pre-emptive strikes against foreign countries making moves. Finally, with the president who hasn’t been seen up until this point, keeping the identity of the actor a surprise. He has to make the final decision of what to do as the missile looms and loss of life seems inevitable. I was fairly enthralled by the immediate pacing and the fraught conversations over doomsday planning. It felt like a modern-day and terrifying version of Fail Safe. There’s even room for some human stories here as people contemplate what might be the end, like trying to reach a loved one by phone and summarize a lifetime of feelings for closure, or debating whether or not to stay or leave the incoming danger. Because of the repeated structure of the screenplay, it holds out the missile striking or not striking until the very end. What will the president do? Is it as another character dubs a choice between suicide and surrender? And then…

Director Kathryn Bigelow’s first movie in eight years plays to her strengths with a dynamite ensemble cast trying to process a ticking clock of doom and their dwindling options. It’s an incredibly taut and thrilling movie elevated by Bigelow’s penchant for later-career verisimilitude. A nuclear missile is launched from an Asian country (North Korea? Russia? It’s never clarified) and heading for the American Midwest. The movie replays the chain of events three times and in real-time, first with the initial discovery of the missile and those in charge of launching counter defenses to take it out (a character describes the difficulty as “shooting a bullet with a bullet”). Then with the higher military brass debating whether to launch pre-emptive strikes against foreign countries making moves. Finally, with the president who hasn’t been seen up until this point, keeping the identity of the actor a surprise. He has to make the final decision of what to do as the missile looms and loss of life seems inevitable. I was fairly enthralled by the immediate pacing and the fraught conversations over doomsday planning. It felt like a modern-day and terrifying version of Fail Safe. There’s even room for some human stories here as people contemplate what might be the end, like trying to reach a loved one by phone and summarize a lifetime of feelings for closure, or debating whether or not to stay or leave the incoming danger. Because of the repeated structure of the screenplay, it holds out the missile striking or not striking until the very end. What will the president do? Is it as another character dubs a choice between suicide and surrender? And then…

Spoiler…

the movie just ends. I’m spoiling to protect you, dear reader. It’s not an ambiguous ending. There is no ending. There is no conclusion. I was flabbergasted. It’s like they lopped off the last twenty minutes. How could they do this? It completely ruins the movie for me and the whole experience becomes one of those distaff “we just want you to think” experiments that don’t function as a fully-developed movie. A House of Dynamite (coined from a podcast the president listened to) is a thriller that goes up in smoke.

Nate’s Grade: B-

You must be logged in to post a comment.