Blog Archives

Snack Shack (2024)

The coming-of-age sub-genre is a familiar and well-worn formula, but with the right filmmaker and voice, it can become refreshingly alive once again, like hearing your favorite song covered by an exciting different artist. Snack Shack is an exuberantly charming movie about one summer with 14-year-old best friends who are constantly running money making schemes and hustles. They overbid to run the concession stand at their community pool, but the best buds are entrepreneurial whizzes and turn the snack shack into a smashing success. There’s plenty of familiar genre elements, from bullies, parents they’ll have more appreciation and understanding from at summer’s end, parties and self-discovery, crushes and jealousies that will test their limits of loyalty; there might not be anything new during these 110 minutes, but it’s the nostalgic authenticity and verve from writer/director Adam Carter Rehmeier (Dinner in America) that makes the movie shine. The movie is practically bristling with details that feel so well-realized and genuine. You’ll enjoy spending time in this world and with these characters, reliving the summer of 1991 in Nebraska. Gabriel LaBelle (The Fabelmans) is fantastic as Moose, more the live-wire, always-smiling, charismatic smooth-talker of the two friends. Every second he’s onscreen makes you inch closer to the screen. I don’t think some of the downer plot turns late in the movie feel like a fit and are there to form the Hard Truths experiences meant to shake the innocence of youth. For a movie this jubilant and sunny, it feels like an abrupt tonal swerve that’s more deferential to genre expectations than the previous vibe of the movie. Despite some minor missteps, the good times cannot be thwarted and Snack Shack is a funny and refreshingly retro peon to being young.

The coming-of-age sub-genre is a familiar and well-worn formula, but with the right filmmaker and voice, it can become refreshingly alive once again, like hearing your favorite song covered by an exciting different artist. Snack Shack is an exuberantly charming movie about one summer with 14-year-old best friends who are constantly running money making schemes and hustles. They overbid to run the concession stand at their community pool, but the best buds are entrepreneurial whizzes and turn the snack shack into a smashing success. There’s plenty of familiar genre elements, from bullies, parents they’ll have more appreciation and understanding from at summer’s end, parties and self-discovery, crushes and jealousies that will test their limits of loyalty; there might not be anything new during these 110 minutes, but it’s the nostalgic authenticity and verve from writer/director Adam Carter Rehmeier (Dinner in America) that makes the movie shine. The movie is practically bristling with details that feel so well-realized and genuine. You’ll enjoy spending time in this world and with these characters, reliving the summer of 1991 in Nebraska. Gabriel LaBelle (The Fabelmans) is fantastic as Moose, more the live-wire, always-smiling, charismatic smooth-talker of the two friends. Every second he’s onscreen makes you inch closer to the screen. I don’t think some of the downer plot turns late in the movie feel like a fit and are there to form the Hard Truths experiences meant to shake the innocence of youth. For a movie this jubilant and sunny, it feels like an abrupt tonal swerve that’s more deferential to genre expectations than the previous vibe of the movie. Despite some minor missteps, the good times cannot be thwarted and Snack Shack is a funny and refreshingly retro peon to being young.

Nate’s Grade: B+

The Bikeriders (2024)

For a four-year period, writer/director Jeff Nichols is a filmmaker who appeared on my Best of the Year list three years, including making my top movie of 2011, Take Shelter. He’s a filmmaker I highly prize, so an eight-year gap from Nichols is an extended leave that makes me personally sad, though his latest movie, The Bikeriders, was delayed by a year after Disney decided to sell it rather than release it for the 2023 awards season. It’s a pretty straightforward drama about a Chicago motorcycle club in the 1960s. It’s all about a group of men that really don’t know how to express their feelings, so it comes out as drinking and fighting and general rebellion against outside authority. These social outsiders find kinship under the leadership of Johnny (Tom Hardy), an unstable man with his own code of honor and retribution. Our narrator is Kathy (Jodie Comer), a plucky woman who falls for a reckless biker, Benny (Austin Butler). There are plenty of interesting moments and sequences, like the rejection of wannabe new members too eager for approval for institutional violence. The changes the club undergoes through the mid 1970s are interesting, especially as the rules of the club begin to fray with the influx of new members and drug addictions, and the challenges to leadership we know will eventually end in tragedy and a betrayal of what the club was intended to be. Regardless, it feels like the movie has all the authentic texture and period details right but is missing a stronger sense of story. It’s more a collage of moments that doesn’t add up to a much better understanding of the three main characters. It’s more like a mood mosaic than engrossing drama, so if you have a general interest in retro motorcycle culture or the time periods, then maybe it will cover the absences in character. I found The Bikeriders to be a good-looking coffee-table book of a movie, more recreation than investment.

For a four-year period, writer/director Jeff Nichols is a filmmaker who appeared on my Best of the Year list three years, including making my top movie of 2011, Take Shelter. He’s a filmmaker I highly prize, so an eight-year gap from Nichols is an extended leave that makes me personally sad, though his latest movie, The Bikeriders, was delayed by a year after Disney decided to sell it rather than release it for the 2023 awards season. It’s a pretty straightforward drama about a Chicago motorcycle club in the 1960s. It’s all about a group of men that really don’t know how to express their feelings, so it comes out as drinking and fighting and general rebellion against outside authority. These social outsiders find kinship under the leadership of Johnny (Tom Hardy), an unstable man with his own code of honor and retribution. Our narrator is Kathy (Jodie Comer), a plucky woman who falls for a reckless biker, Benny (Austin Butler). There are plenty of interesting moments and sequences, like the rejection of wannabe new members too eager for approval for institutional violence. The changes the club undergoes through the mid 1970s are interesting, especially as the rules of the club begin to fray with the influx of new members and drug addictions, and the challenges to leadership we know will eventually end in tragedy and a betrayal of what the club was intended to be. Regardless, it feels like the movie has all the authentic texture and period details right but is missing a stronger sense of story. It’s more a collage of moments that doesn’t add up to a much better understanding of the three main characters. It’s more like a mood mosaic than engrossing drama, so if you have a general interest in retro motorcycle culture or the time periods, then maybe it will cover the absences in character. I found The Bikeriders to be a good-looking coffee-table book of a movie, more recreation than investment.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Nickel Boys (2024)

This might be the most immersive and biggest directorial swing of the year. Director/co-writer RaMell Ross adapts the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead about a reform school for juveniles more like a prison during the Civil Rights era. Ostensibly, the Nickel Academy is an institution that is meant to teach moral lessons and responsibility through outdoor labor. In reality, it’s a school that benefits from labor exploitation and has no intention of fulfilling its promise that students can possibly leave before they turn eighteen. This is even worse for African-Americans, as the school is also segregated and the students have to endure the racism of the administrators and other white juvenile delinquents who still want to feel superior to somebody. It’s a cruel setting destined to spark risable outrage, especially knowing that our main character, Elwood Curtis, is a victim of profiling and being in the wrong place at the wrong time, a star student selected to take college classes at an HBCU. The big artistic swing of Nickel Boys is the choice to tell the entire movie through first-person perspective, with the camera functioning as our protagonist’s eyes and ears. As the camera moves, it is us moving. It makes the movie intensively immersive, but I had some misgivings about this storytelling gimmick. It limits the resonance of the central performance as we can’t see the actor and his expressions and emotions, which I found frustrating. Ross also decides to do this same trick twice with a second character who befriends Elwood. Now we can see more of our main character, through this other person’s eyes occasionally, but it’s also like having to re-learn the visual vocabulary, and switching from viewpoints was distracting for the immersion and to recall whose eyes were whose at any moment. There’s also flash-forwards to adult Elwood that only served to muddle the tension. There’s enough genuine drama in this setting that I wish Nickel Boys might have been a more traditionally-made drama. Still, it’s a fine movie, but the aspect that will make it stand out the most is also what I feel that holds it back for me from being more profoundly affecting.

This might be the most immersive and biggest directorial swing of the year. Director/co-writer RaMell Ross adapts the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead about a reform school for juveniles more like a prison during the Civil Rights era. Ostensibly, the Nickel Academy is an institution that is meant to teach moral lessons and responsibility through outdoor labor. In reality, it’s a school that benefits from labor exploitation and has no intention of fulfilling its promise that students can possibly leave before they turn eighteen. This is even worse for African-Americans, as the school is also segregated and the students have to endure the racism of the administrators and other white juvenile delinquents who still want to feel superior to somebody. It’s a cruel setting destined to spark risable outrage, especially knowing that our main character, Elwood Curtis, is a victim of profiling and being in the wrong place at the wrong time, a star student selected to take college classes at an HBCU. The big artistic swing of Nickel Boys is the choice to tell the entire movie through first-person perspective, with the camera functioning as our protagonist’s eyes and ears. As the camera moves, it is us moving. It makes the movie intensively immersive, but I had some misgivings about this storytelling gimmick. It limits the resonance of the central performance as we can’t see the actor and his expressions and emotions, which I found frustrating. Ross also decides to do this same trick twice with a second character who befriends Elwood. Now we can see more of our main character, through this other person’s eyes occasionally, but it’s also like having to re-learn the visual vocabulary, and switching from viewpoints was distracting for the immersion and to recall whose eyes were whose at any moment. There’s also flash-forwards to adult Elwood that only served to muddle the tension. There’s enough genuine drama in this setting that I wish Nickel Boys might have been a more traditionally-made drama. Still, it’s a fine movie, but the aspect that will make it stand out the most is also what I feel that holds it back for me from being more profoundly affecting.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Brutalist (2024)

The indie sensation of the season is an ambitious throwback to meaty movie-going of the auteur 1970s, telling an immigrant’s expansive tale, and at an epic length of 3 hours and 30 minutes, and an attempt to tell The Immigrant Story, and by that we mean The American Story. It’s a lot for any movie to do, and while The Brutalist didn’t quite rise to the capital-M “masterpiece” experience so many of my critical brethren have been singing, it’s still a very handsomely made, thoughtfully reflective, and extremely well-acted movie following one man trying to start his life over. Adrien Brody plays Laszlo Toth, A Jewish-Hungarian survivor of the Holocaust who relocates to Pennsylvania in 1947. He starts work delivering furniture before getting a big break redesigning a rich man’s library as a surprise birthday gift that doesn’t go over well. Years later, that same rich man, Harrison Lee (Guy Pearce), wants to seek out Laszlo because his library has become a celebrated example of modern architecture. He proposes Laszlo design a grandiose assembly that will serve as a community center, chapel, library, gymnasium, and everything to everyone, standing atop a hill like a beacon of twentieth-century civilization. Everything I’ve just written is merely the first half of this massive movie, complete with an old-fashioned fifteen-minute intermission.

The second half is about crises professional and personal for Laszlo; the meddling and compromises and shortfalls of his big architectural project under the thumb of Harrison, and finding and bringing his estranged wife (Felicity Jones) to America and dealing with the aftermath of their mutual trauma. I was never bored with writer/director Brady Crobett’s (Vox Lux) movie, which is saying something considering its significant length. The scenes just breathe at a relaxed pace that feels more like real life captured on film. The confidence and vision of the movie becomes very clear, as Corbett painstakingly takes his time to tell his sprawling story on his terms. I can appreciate that go-for-broke spirit, and The Brutalist has an equal number of moments that are despairing as they are enlightening. I was more interested in Laszlo’s relationship with his wife, now confined to a wheelchair. There are clear emotional chasms between them to work through, having been separated at a concentration camp, but there is a real desire to reconnect, to heal, and to confront one another’s challenges. It’s touching and the real heart of the movie, and it easily could have been the whole movie. The rest, with Laszlo butting heads against moneymen to secure the integrity of his vision, is an obvious allegory for filmmaking or really any artist attempt to realize a dream amidst the naysayers. The acting is terrific across the board, with Brody returning to a form he hasn’t met in decades. Maybe his career struggles since winning the Best Actor Oscar in 2003 have only helped imbue this performance with a lived-in quality of a soul-searching artist. Pearce is commanding and infuriating as the symbol of America’s ego and sense of superiority. The musical score is unorthodox but picks up a real sense of momentum like a locomotive, thrumming along at a building pace of progress. The only real misstep is an unnecessary epilogue that spells out exactly how you should feel about the movie rather than continuing the same respect and trust for its patient audience. The Brutalist is an intimidating movie and one best to chew over or debate its portrayal of the American Dream, and while not all of its artistic swings connect, the sheer ambition, fortitude, and confident execution of the personal and the grandiose is worth celebrating and elevating.

Nate’s Grade: B

Nosferatu (2024)

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Nate’s Grade: B

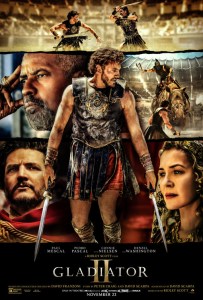

Gladiator II (2024)

It’s been twenty-four years since Russel Crowe, in his Oscar-winning role, bellowed, “Are you not entertained?” We were, we really were, and Gladiator was a huge hit in 2000 but has also held up as a twenty-first century classic that revived the sword-and-sandals epic. The late sequel hews quite closely to the path of the original Gladiator, a rare example of a movie that was quite literally writing the script as they went and succeeded wildly. The second go-round has a strong same-y feel, which is natural with sequels, but it also has trouble simply standing in the shadow of its superior predecessor.

It’s been twenty-four years since Russel Crowe, in his Oscar-winning role, bellowed, “Are you not entertained?” We were, we really were, and Gladiator was a huge hit in 2000 but has also held up as a twenty-first century classic that revived the sword-and-sandals epic. The late sequel hews quite closely to the path of the original Gladiator, a rare example of a movie that was quite literally writing the script as they went and succeeded wildly. The second go-round has a strong same-y feel, which is natural with sequels, but it also has trouble simply standing in the shadow of its superior predecessor.

This time we follow Paul Mescal (Aftersun) as a Roman expat who’s been living abroad as a simple man of the people, except when violence is called upon. His land is conquered by Rome, his beloved is killed, and he’s sold into slavery only to be selected to be trained as a gladiator and only to become a fan favorite who could possibly unseat the Emperor(s). Sounds familiar, right, plus with the revenge motivation? Mescal is playing Lucius, the adult nephew to the late emperor played by Joaquin Phoenix. He’s all grown up and with abs. This Maximum stand-in is actually the blandest character in the film, a scolding figure who says little and doesn’t want to be in any position of leadership. It makes for a lackluster hero especially compared to the presence and magnetism of Crowe in his leading man prime. Fortunately there’s entertaining side characters, notably Denzel Washington (The Equalizer) as a bisexual wheeler-dealer who manipulates his way to the top of the Roman Senate, even garnering the attention of the hedonist twin emperors. The script utilizes a lot of conveniences, from revelations of bloodlines to an adjacent crypt that just so happens to have old Maximus’ armor and sword. Washington’s schemes, more loose-goosey and the benefit of convenient luck than machiavellian plotting, provide the missing entertainment value from Mescal’s underdog-seeking-vengeance arc. Director Ridley Scott returns and stages some fun Colosseum action set pieces, including an aquatic based naval battle with literal sharks. The opening siege against a coastal city by the powerful Roman army is wonderfully visualized. I was never bored but I can’t say that the movie is operating at close to the same level. The second half kind of creaks to a close, with a final one-on-one that feels too lopsided and unfulfilling. The emotional resonance of the prior movie is sufficiently lacking. While Gladiator II can still get your blood moving, it’s also an exercise in rote blood-letting as diminished franchise returns.

Nate’s Grade: B-

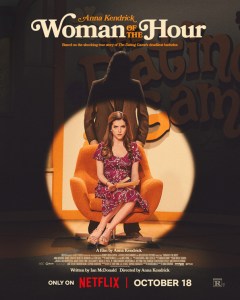

Woman of the Hour (2024)

I never knew there was an actual serial killer that appeared on a 1978 episode of The Dating Game, and that he actually won. That’s a killer hook. The problem with Woman of the Hour, Anna Kendrick’s debut as a director, is that there isn’t really a movie here as presented. Because the game show segment can only last so long, we get the creepy first date, that never happened in real life, and watch Kendrick playing our lucky lady with mounting dread. A moment where the killer requests that she re-read the phone number she hastily gave him by memory, because she should know her number, is terrifically tense, as is the scene of him following her to her car. The problem is that this first date can only last so long, just as the cheesy TV game show segment can only last so long, so the movie has to provide extra back-story to fill the time. We get several past encounters with the killer’s unfortunate victims, all played quite unnervingly and seriously. The woman of the hour is less Kendrick getting her fleeting spotlight on TV, and an anecdote to impress people at parties for the rest of her life, than the survivor who eventually leads to the killer’s arrest. Amazingly, at the time of his TV appearance, he was on the FBI’s Most Wanted List but there wasn’t a searchable database, so he clumsily got to keep committing murders, including while out on bail. It’s a harrowing story, but is it one best told through the gimmick structure of the game show appearance? If you were going this route, perhaps best to treat the material like a slow-burn stage play, starting with the first date, and watch in real time as it gets awkward and our heroine begins to have her suspicions that this man does not mean her well. Instead, the game show segments are goofy and broad and the least important moments in the stretched-thin film. There might be a movie with this subject, but I’m not sure that Woman of the Hour is it.

I never knew there was an actual serial killer that appeared on a 1978 episode of The Dating Game, and that he actually won. That’s a killer hook. The problem with Woman of the Hour, Anna Kendrick’s debut as a director, is that there isn’t really a movie here as presented. Because the game show segment can only last so long, we get the creepy first date, that never happened in real life, and watch Kendrick playing our lucky lady with mounting dread. A moment where the killer requests that she re-read the phone number she hastily gave him by memory, because she should know her number, is terrifically tense, as is the scene of him following her to her car. The problem is that this first date can only last so long, just as the cheesy TV game show segment can only last so long, so the movie has to provide extra back-story to fill the time. We get several past encounters with the killer’s unfortunate victims, all played quite unnervingly and seriously. The woman of the hour is less Kendrick getting her fleeting spotlight on TV, and an anecdote to impress people at parties for the rest of her life, than the survivor who eventually leads to the killer’s arrest. Amazingly, at the time of his TV appearance, he was on the FBI’s Most Wanted List but there wasn’t a searchable database, so he clumsily got to keep committing murders, including while out on bail. It’s a harrowing story, but is it one best told through the gimmick structure of the game show appearance? If you were going this route, perhaps best to treat the material like a slow-burn stage play, starting with the first date, and watch in real time as it gets awkward and our heroine begins to have her suspicions that this man does not mean her well. Instead, the game show segments are goofy and broad and the least important moments in the stretched-thin film. There might be a movie with this subject, but I’m not sure that Woman of the Hour is it.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released September 17, 2004:

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow started as a six-minute home movie by Kerry Conran. He used computer software and blue screens to recreate New York City and depict a zeppelin docking at the top of the Empire State building. The six-minute short, which Conran spent several years completing, caught the attention of producer John Avnet (Fried Green Tomatoes). He commissioned Conran to flesh out a feature film, where computers would fill in everything except the actors (he even used the original short in the feature film). The dazzling, imaginative results are Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

Polly (Gwyneth Paltrow) is a reporter in 1930s New York. She?s investigating the mysterious disappearance of World War scientists when the city is invaded by a fleet of robots. The city calls out for the aid of Sky Captain, a.k.a. Joe (Jude Law), a dashing flying ace that happens to also be Polly?s ex. Joe and Polly form an uneasy alliance. He wants to stop Totenkopf (archived footage of Laurence Olivier) from sending robots around the globe and rescue his kidnapped mechanic, Dex (Giovanni Ribisi). She wants to get the story of a lifetime, a madman spanning the world to abduct scientists, parts, and the required elements to start a doomsday device. Along the way, Captain Franky Cook (Angelina Jolie) lends her help with her flying amphibious brigade. Together they might stop Totenkopf on his island of mystery.

Sky Captain is a visual marvel. It isn’t necessary a landmark, as actors have performed long hours behind green screen before (just look at the Star Wars prequels). Sky Captain is the first film where everything, excluding props the actors handle, is digitally brought to life inside those wonderful computers. The results are breath-taking, like when Polly enters Radio City Music Hall or during an underwater dogfight with Franky’s amphibious squadron. Sky Captain is brimming with visual excitement. The film is such an idiosyncratic vision that there’s no way it could have been made within the studio system.

Sky Captain has definite problems. For one, the characters are little more than stock characters going through the motions. The story also takes a backseat to the visuals. The dialogue is wooden and full of clunkers like, “You won’t need high heels where we’re going.” Generally the dialogue consists of one actor yelling the name of another character (examples include: “Dex!” “Joe!” “Polly!” and “Totenkopf!”). My father remarked that watching Sky Captain was akin to watching What Dreams May Come, because you’re captivated by the painterly visuals enough to stop paying attention to the less-than-there story and characters. The characters running onscreen also appears awkward, like they’re running on treadmills we can’t see, reminiscent of early 1990s video games.

Let’s talk then about those characters then. Paltrow’s character is generally unlikable. She’ll scheme her way toward whatever gains she wishes, but not in a chirpy Lois Lane style, more like a tabloid reporter. She whines, she yells, she complains, she berates, and she doesn’t so much banter as she does argue. Sky Captain is more enigmatic as a character. He seems forever vexed. Jolie’s Captain Franky Cook gives her another opportunity for her to use her faux-British accent. Jolie’s character is the strong-willed, sexy, helpful heroine that should be the center of the film, not Paltrow’s pesky reporter.

It’s also a bit undignified to assemble Laurence Olivier as the villain. It’s very unnecessary, but at least he wasn’t dancing with a vacuum cleaner.

Now, having acknowledged the flaws of Sky Captain, I must now say this: I do not care at all. This is the first time I’ve totally sidestepped a film’s flaws because of overall enjoyment. I have never felt as giddy as I did while watching Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. When the giant robots first showed up I was hopping in my seat. When I saw the mixture of 1930s sci-fi, adventure serials, and Max Fleischer cartoons, I was transported to being a little kid again. No movie has done this so effectively for me since perhaps the first Back to the Future. I loved that we saw map lines when we traveled from country to country. I love the fact that the radio signal hailing Sky Captain is reminiscent of the RKO Pictures opening.This is a whirling, lovelorn homage that will make generations of classic movie geeks will smile from ear to ear. I don’t pretend to brush over the flaws, with which story and characters might be number one, but Sky Captain left me on such a cotton-candy high that my eyes were glazing over.

One could actually make a legitimate argument that the stock characters, stiff dialogue, and anemic story are in themselves a clever homage to the sci-fi serials of old, where the good guys were brave, the women plucky, and the bad guys always bent on world domination. I won?t make this argument, but it could lend credence more toward the general flaws of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

Sky Captain is an exciting ode to influences of old. It’s periodically breath-taking in its visuals and periodically head scratching with its story, but the film might awaken childhood glee within the viewer. I won’t pretend the film isn’t flawed, and I know the primary audience that will love Sky Captain are Boomers with a love and appreciation for classic cinema. Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow will be a blast for a select audience, but outside of that group the film’s flaws may be too overwhelming.

Nate’s Grade: B+

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

When I first watched Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow in 2004, I was dazzled by its gee-whiz retro-futuristic homages and cutting-edge special effects. I wrote it felt like an appeal to your “Dad’s cinephile dad,” tapping into adventure serials and quaint sci-fi of Old Hollywood like Metropolis and Flash Gordon and German Expressionism and Max Fleischer cartoons. It was a giant nostalgic bombardment to a cinephile’s pleasure center. Now twenty years later, re-watching Sky Captain leaves me with a very different feeling. I found the majority of the movie in 2024 to be rather boring, and the special effects, while immersive and something special twenty years prior, are now dated and flawed. The whole thing propping up this underwritten homage enterprise are these murky visuals, making the ensuing 100 minutes feel much longer and more strained. It was transporting for me back in 2004, but now it just feels like empty homage run amok and lifted by special effects marked with an asterisk of history.

Sky Captain reminds me of 2001’s Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, a momentary breakthrough at the time of its release in special effects technology that was inevitably to be passed, thus serving as little more than a footnote in visual effects history. It’s now less compelling to revisit. At the time, entire movies weren’t constructed on giant green screen stages and completely in the powerhouse computers processing new worlds of imagination. Now, it feels like most studio blockbusters above a certain budget are completely shot on large, empty green screen warehouses. Now we have entire movies constructed in a three-dimensional play space inside a computer, like 2016’s The Jungle Book and 2019’s The Lion King. It wasn’t even that much longer before another artist would replicate writer/director Kerry Conran’s everything-green-screen-for-maximum-style approach. Just a few months later, in April 2005, Robert Rodriguez released the highly stylized Sin City movie, bringing to vivid life the striking monochromatic artwork of Frank Miller’s celebration of film noir, pulp comics, and busty dames. In that case, the visuals nearly pop off the screen, fashioning something that cannot be served through live-action alone. Re-watching Sky Captain, I found a lot of the visual effects to be dark and blurry, like the filmmakers added a grimy filter. Maybe it was an ode to making the effects less polished to better replicate its older influences, or maybe it was simply a matter of hiding its budget, but the effect is still the same, making the onscreen visuals that much harder to fully observe and appreciate. If the appeal is going to be the then-cutting-edge special effects, then don’t make choices that will mitigate that appeal.

The story is so episodic and flimsy, held together only by the references it bestows. I understand that Conran was trying to recreate the screwball banter of Old Hollywood, but I found the relationship between Sky Captain (Jude Law) and his ex Polly Perkins (Gwyneth Paltrow) to be excruciating. The bickering is heightened, as the overall tone of the movie is generally heightened, but that makes all human interaction feel wrongly calibrated. Polly comes across as obnoxious, worthy of being booted at many points throughout the globe-trotting adventure. She gets into trouble repeatedly while whining about her big journalistic scoop, or rehashing who was at fault for the detonation of their relationship. I think Law has better chemistry with Angelina Jolie, who appears late as a flying navy commander, and even Giovanni Ribisi as Sky Captain’s trusty ace mechanic. These people feel like they understood the assignment, playing into the heightened pulpy nature. Paltrow is hitting the wrong notes from the start, so her character comes across as annoying and in constant need of rescue. There’s a reason that Conran keeps the plot busy and skipping from one set piece to another, because the more time spent with our two main characters the more you realize they would be better served as transitory archetypes in a short film.

In many ways, it feels like Conran was worried that he might never direct another movie again, and so Sky Captain includes just about every nod possible to his influences. It can become its own Easter egg guessing game, making all the connections to stories film properties of old, like King Kong, War of the Worlds, The Wizard of Oz, to lesser known titles like Captain Midnight and King of the Rocket Men. There’s hidden worlds with dinosaurs, spaceship arks for a fresh start, and Laurence Olivier reappearing as manipulated archival footage as our mysterious deceased mad doctor. It’s somewhat fun to watch Conran be so transparent about his passions and influences. However, all these reverent homages and special effects closed loops are attached to a thin story with grating characters. Again, for a very select audience, dissecting all the reference points will be its own entertainment. For most viewers, Sky Captain will be a tin-eared bore that keeps throwing more reference points into its ongoing stew. Any ten minutes chosen at random will have the same value and impact as any other ten minutes throughout the movie.

Perhaps Conran was prescient because he has no other feature film credits in the ensuing twenty years. There was a point where he was attached for the big screen John Carter of Mars adaptation (as was Robert Rodriguez at one point) but he eventually left for unknown creative reasons. Considering how much buzz Sky Captain had as a project from an unknown outside the system, you might think it would serve as a proof of concept to at least get Conran to helm some other mid-level studio project.

The lasting legacy of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow will be its look, now replicated by many studio blockbusters, though Conran and his team did so without the same studio coffers. The thing I’ll remember most about Sky Captain isn’t my own enjoyment but my father;s a man who grew up reading pulp sci-fi magazines, watching saucer men movies, and instilling in me a love of older movies. I remember the delight this movie seemed to unleash inside him, returning him to a euphoric sense of his childhood. That’s the association I’ll have with this movie, even if my own entertainment level and appreciation has noticeably dipped in twenty years. I know there are other fans out there who may feel that same childlike wonder and glee from the movie. I hope you do, dear reader. For me, for now, it’s like seeing behind the magic trick and wishing you could still feel the same current of exhilaration. Alas.

Nate’s Grade: C

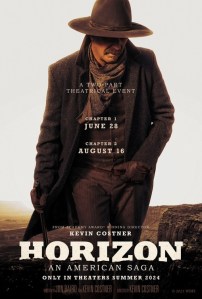

Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 (2024)

I admire Kevin Costner throwing out all the stops to achieve his passion, a four-part, twelve-hour film series to showcase a sprawling Western epic. The man put a hundred million of his own money into the first two parts of Horizon: An American Saga, and the time devoted to this project was so all-consuming that Costner quit the Yellowstone series, a cable TV juggernaut getting bigger ratings every season. It’s ballsy all right, to abandon a monumentally successful series at the height of its zeitgeist popularity so he can direct not just one but four throwback Westerns that will ultimately be as long as the Lord of the Rings trilogy. It’s rare to see this level of sheer chutzpah in Hollywood. Horizon’s first part was released in June, with its completed second part intended to be released a mere two months later in August. After the poor box-office of Part One, the studio decided to pull Part Two from the release schedule, ostensibly to give people more time to catch the first movie. Will we ever see Part Two in theaters? Will we ever see Part Three, which Costner is currently filming, or Part Four, which Costner is currently raising money for? Costner intended to release the whole saga as a miniseries upon completion, and this might be the best case scenario. As a movie, albeit one quarter of an intended whole, Horizon Part One feels far more structured as an incomplete and rather prosaic TV series.

Upon the completion of the 170 minutes, I was left wondering what was here that would make someone want to come back for a lengthy second part, let alone a third and a fourth. It doesn’t feel like a complete movie or even a completed chapter, and again let me cite Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series. Released over the course of three years, each movie had its own form of a beginning, middle, and end, with each climaxing around some event that left one satisfied by its conclusion. They didn’t just feel like chapters linking to the next; they felt like completed stories that pushed forward a larger overall story. Now, with Horizon Part One, it doesn’t feel like a three-hour movie, rather like three one-hour episodes of a TV series. Each of those hours feels too separate from the other. I’m reminded of television in the streaming era, where producers anticipate viewers binging through multiple episodes in speedy succession. This tacit assumption lends itself toward the general pacing issues I find with too many streaming series, where the filmmakers take far too long to get things moving in a significant manner. I’m reminded of a joke by Topher Florence that back in the day a show like Surf Dracula would feature its lead character surfing in weekly adventures, but the streaming age version would take its entire first season showing how he got his surfboard and then spend five minutes surfing in the finale. When you’re pacing out only one quarter of your possible intended story, calling it slow and lacking development and payoffs is an obvious hazard, which is why every movie needs to be its own thing, to provide a sense of conclusion even if it’s not the final conclusion.

Part One is divided into three parts: 1) the early settlers of Horizon, in the San Pedro Valley, being massacred by the Apache, 2) an old gunslinger (Kevin Costner) tasked with protecting a woman and child on the run from vengeful gunmen, 3) a wagon train of settlers headed to Horizon. Now, from that very streamlined synopsis, which of those storylines sounds the most exciting? Which of those storylines sounds like it can lend itself toward having an in-movie climax? Which of these storylines feels the most fraught with danger and intrigue? It’s the one starring Costner himself, of course, fitting naturally into the role of a tough curmudgeon.

I’m confused why the entire first hour of this movie is devoted to following the frontier town when we’re only going to get two survivors total that go forward. As far as its narrative importance, this entire section could have been condensed to a terrifying flashback from Frances Kittredge (Sienna Miller) and her daughter after the fact. The majority of this hour is spent watching the fine Christian folk of the early days of Horizon die horribly. We’re confined inside the battered Kittredge home that serves as the foundation of a siege thriller, with the band of various townspeople trapped and trying to fight off their indigenous intruders. The attack is prolonged and unsparing in its violence, eliminating all these nice, smiling faces from before. What does it add up to? It’s the tragic back-story for Frances, but it also makes her conveniently romantically unattached so that the nice cavalryman, Trent Gephart (Sam Worthington), can swoon and she can Learn to Love Again. It also sets up a young Apache warrior, Pionsenay (Owen Crow Shoe), making aggressive moves that his elders disagree with in their continued efforts to find some balance with the American settlers grabbing their territory. It also sets up what serves as the only possible character arc completion, with young Russell (Etienne Kellici) escaping the massacre in the beginning to then witness a massacre of Apache, and as he observes the scalping butchery, it galls him, not providing the relief of vengeance he had sought. Now that’s a conceivably emotional storyline, but Russell isn’t the primary character, or even one of the most essential supporting characters. You might genuinely forget about him like I did.

Something else I forgot an hour in was that Part One opens with Ellen Harvey (Jena Malone) shooting her abusive husband and running out. This prologue eventually comes back to setting up the present-day conflicts of the second hour, where Ellen has started a new life as Lucy with her young son. She lives in the Wyoming territory with a prostitute, Marigold (Abbey Lee). This storyline picks up significantly with new characters coming into the mix and disrupting the status quo. The first is Hayes Ellison (Costner) who finds himself attracted to Marigold, perhaps recognizing a woman in over her head. The second are the Sykes brothers (Jamie Campebell Bower, Jon Beavers) who have come looking to retrieve Lucy and her child, the son of their dearly departed pa who was slain in the opening. I am astounded that Costner decided to make the audience wait an hour for this segment because it feels like a much better fit to open Part One. There’s an immediacy to the looming danger and the consequences of actions, and what would serve as the Act One break is when Hayes has to intervene at great risk. This is, by far, the best segment of Horizon Part One. The ensuing on-the-run segment doesn’t get much further, setting up ongoing antagonism between the two sides that presumably will come to blows again. It’s not exactly reinventing the wagon wheel here: drifter reluctantly becoming protector for the vulnerable and reckoning with his shady past and trying to make amends. However, for this first movie, at least this storyline provides a sustained level of engagement with needed urgency.

The weakest portion is the wagon train led by Matthew Van Weyden (Luke Wilson). The most significant conflict during this section isn’t even the protection of the wagon train, it’s whether or not the hoity-toity British couple (Tom Payne, Anna and the Apocalypse‘s Ella Hunt) will assimilate to life on the prairie. They’re privileged, though at least he seems to recognize this. She bathes in the drinking water supply in an extended sponge bath sequence that feels so oddly gratuitous and leery. Two scouts are caught eagerly peeping and this seems like the most significant conflict of this whole section. They’re headed for Horizon, the setting of tragedy and indigenous conflict we know, but the entire wagon train lacks any feeling of dread or even the opposite, a feeling of yearning for a new life. It’s just a literal pileup of underwritten characters in movement without giving us a reason to care.

Costner’s Western eschews the trappings of modern revisionism, deconstructing the heroism and Manifest Destiny mythology of popular Wild West media. This isn’t a deconstruction but a full blown romantic classical Western, embracing the tropes with stone-faced gusto. In some ways it feels like Costner’s version of a Taylor Sheridan show (1883, Yellowstone). He left a Sheridan show to make his own Sheridan show. It’s more measured in its portrayal of the Native Americans even as it shows them massacring men, women, and children as our first impression. I wager Costner is showing that the evils of violent tendencies pervade both sides of the conflict, with a troop of American scalp-hunters that don’t really care where those scalps come from. It’s hard to fully articulate the themes given this is only one-fourth of the overall intended picture. The expansive settings are stunning and gorgeously filmed. I can understand why Costner would want people to watch this movie on the big screen with scenery this beautiful from cinematographer J. Michael Muro, who served as Costner’s DP on 2003’s Open Range, another muscular Western. Fun fact: Muro also served as a Steadicam operator on Costner’s Best Picture-winning Dances with Wolves, so their professional relationship goes back thirty-five years and covers Costner’s love affair with Westerns.

During its conclusion, Horizon: An American Saga runs through a wordless montage of clips that serves as a trailer for the forthcoming Part Two. It’s not edited like a trailer, more so a very leisurely preview with clips that look good but, absent context, can be shrug-worthy. Oh look, a character looking out a window pensively. Oh look, a character walking along a trail. Oh look, a character dismounting from a horse. Oh look, another character looking out a window pensively. It’s hard for me to fathom this truncated preview getting too many people excited for what Part Two has to offer, but then I think that’s the same problem with Part One. It doesn’t serve as a grabber, with characters we really care about, with conflicts that keep us glued, and with revelations and character turns that can keep us intrigued and desperately wanting more. It’s hard for me to think of that many people walking out of Part One and being ravenous for nine more hours. I accept that stories might feel incomplete and characters might feel disjointed, but Horizon is perhaps a Western best left in the distance, at least until you can binge it in its completed form, whatever that may be, though I doubt we’re going to get four full movies. Ultimately, Costner’s opus will need to be judged as a whole rather than as consecutive parts.

Nate’s Grade: C

Unfrosted (2024)

What to make of a movie like Netflix’s Unfrosted. It’s Jerry Seinfeld’s directorial debut, working off a screenplay he co-wrote, his first foray into film writing and acting since 2007’s Bee Movie. His eponymous sitcom “about nothing” was a 1990s mainstay and popularized an ironic meta form of comedy that still continues to dominate comedic tastes. Making a movie about the pseudo history of the invention of Pop Tarts, and the corporate rivalry between the major cereal brands, seems like a further exercise in that realm of humor, potentially satirizing a burgeoning sub-genre of late, the Biopic of Products (Air, Tetris, Flamin’ Hot, Blackberry). Except this supposed “biopic about nothing” is really a head-scratcher. Its humor feels pained and stale, the satire feels missing or glancing at best, and it seems like an expensive lark, wasting the nigh-infinite money of Netflix to purposely make a stupid comedy with all his friends.

What to make of a movie like Netflix’s Unfrosted. It’s Jerry Seinfeld’s directorial debut, working off a screenplay he co-wrote, his first foray into film writing and acting since 2007’s Bee Movie. His eponymous sitcom “about nothing” was a 1990s mainstay and popularized an ironic meta form of comedy that still continues to dominate comedic tastes. Making a movie about the pseudo history of the invention of Pop Tarts, and the corporate rivalry between the major cereal brands, seems like a further exercise in that realm of humor, potentially satirizing a burgeoning sub-genre of late, the Biopic of Products (Air, Tetris, Flamin’ Hot, Blackberry). Except this supposed “biopic about nothing” is really a head-scratcher. Its humor feels pained and stale, the satire feels missing or glancing at best, and it seems like an expensive lark, wasting the nigh-infinite money of Netflix to purposely make a stupid comedy with all his friends.

Set in the mid 1960s, we follow two households, both alike in dignity, in fair Battle Creek, Michigan where we lay our scene. Kellogg’s has been the dominant cereal-brand for years but its chief rival, Post, is set to launch a new product that will revolutionize breakfast mornings. Bob (Seinfeld) is the head of development for Kellogg’s and reaches out to his old colleague, Donna (Melissa McCarthy), when it becomes evident that Post stole their unused research to develop a pastry treat designed to be cooked in one’s toaster. The warring CEOs, with Jim Gaffigan as Edsel Kellogg III and Amy Schumer as Marjorie Post, are desperate to one-up one another and be seen as more than an inheritor of their family’s wealth. It’s a race to see which company can get their treat to market first and capture the hearts, minds, and sweet teeth of America’s youth.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t laugh at points through Unfrosted, which operates like a spoof movie on a slower jokes-per-second pacing guide. There are zany sight gags amidst broadly drawn characters treating the silly straight, though occasionally you’ll have wisecrackers commenting on the inherent absurdity of moments, mostly confined to the stars making asides to the audience. Sometimes it’s lazy jokes that rely upon our foreknowledge, like when Bob coins a NASA beverage by saying it has a “real tang” (get it?). The movie frequently intensifies into goofy escalation when Kellogg’s impanels a team of mascots and inventors as a breakfast brain trust. Every one of these wacky characters is here to provide the exact same joke they will provide throughout the movie, and their inclusion is already suspect. Having the Schwinn bicycle guy (Jack McBrayer) comment on why he should be there is not enough. The hit-to-miss ratio will vary per everyone’s personal sense of humor, but overall I just felt mystified why this project would tempt Seinfeld from his comedy repose. What about this idea excited him? Was it just his lifelong love of cereal and Pop Tarts, a topic from his standup act decades ago? I ate a lot of cereal as a teenager too but I don’t want to make a movie about the Lucky Charms advertising campaign teaching children to beat and pillage the Irish (maybe Ken Loach could direct – to the three people on the Internet who appreciate this joke, I want you to know I appreciate you also).

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t laugh at points through Unfrosted, which operates like a spoof movie on a slower jokes-per-second pacing guide. There are zany sight gags amidst broadly drawn characters treating the silly straight, though occasionally you’ll have wisecrackers commenting on the inherent absurdity of moments, mostly confined to the stars making asides to the audience. Sometimes it’s lazy jokes that rely upon our foreknowledge, like when Bob coins a NASA beverage by saying it has a “real tang” (get it?). The movie frequently intensifies into goofy escalation when Kellogg’s impanels a team of mascots and inventors as a breakfast brain trust. Every one of these wacky characters is here to provide the exact same joke they will provide throughout the movie, and their inclusion is already suspect. Having the Schwinn bicycle guy (Jack McBrayer) comment on why he should be there is not enough. The hit-to-miss ratio will vary per everyone’s personal sense of humor, but overall I just felt mystified why this project would tempt Seinfeld from his comedy repose. What about this idea excited him? Was it just his lifelong love of cereal and Pop Tarts, a topic from his standup act decades ago? I ate a lot of cereal as a teenager too but I don’t want to make a movie about the Lucky Charms advertising campaign teaching children to beat and pillage the Irish (maybe Ken Loach could direct – to the three people on the Internet who appreciate this joke, I want you to know I appreciate you also).

It can be fun to simply watch dozens of famous people take their turns being silly in what is unquestionably a “dumb comedy.” When you have comedians of this quality in your movie, they’ll find ways to make even so-so jokes hit a little better, and that’s the case here. There’s an entertainment value in just wondering who will show up next, as many characters are only onscreen for a single scene or an abbreviated moment. Unfrosted becomes an example of Seinfeld’s industry power as he empties his Rolodex to fill even the tiniest of roles. Look, it’s James Marsden as Jack LaLanne. Look, it’s Bill Burr as JFK and Dean Norris as Kruschev (double Breaking Bad). Peter Dinklage as the head of the nefarious milkmen cartel? Why not? If you set your expectations low, maybe lower than what you were accounting for, there can be a mild amusement scene-to-scene just seeing who might show up next, almost like a modern-day version of those anarchic big ensemble comedies like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

There is one segment that fell so flat for me that I was in utter amazement, and that was the unexpected January 6th insurrection parody. In a movie that has sustained a surreal and offbeat version of our universe, it evokes one of the most startling days of recent history. I think the humor is meant to derive from simply seeing a bunch of mascots in big colorful costumes as a mob running havoc, but there’s no jokes about like the challenges of a mascot costume in a fight, or say someone tipping over and being unable to get back up like a helpless turtle. There are jokes that can be had with this scenario, but instead Seinfeld is relying on the ironic juxtaposition of the ridiculous with the serious, and I don’t think it ever works as a joke. My sinking feeling began when Hugh Grant’s embittered mascot character wore a headdress resembling the QAnon shaman. It feels tacky and strange and the longer it persists the more I kept wondering what Seinfeld was doing with this. Why include this especially as the only form of relatively topical political humor, beyond, I guess, the depiction of business elites being complete morons? Why this? Again, it would be different if it was funny in execution, like the Saving Private Ryan D-Day parody from Sausage Party. This just isn’t funny, and its inclusion feels so odd compared to the stale nature of its other comedy.

There is one segment that fell so flat for me that I was in utter amazement, and that was the unexpected January 6th insurrection parody. In a movie that has sustained a surreal and offbeat version of our universe, it evokes one of the most startling days of recent history. I think the humor is meant to derive from simply seeing a bunch of mascots in big colorful costumes as a mob running havoc, but there’s no jokes about like the challenges of a mascot costume in a fight, or say someone tipping over and being unable to get back up like a helpless turtle. There are jokes that can be had with this scenario, but instead Seinfeld is relying on the ironic juxtaposition of the ridiculous with the serious, and I don’t think it ever works as a joke. My sinking feeling began when Hugh Grant’s embittered mascot character wore a headdress resembling the QAnon shaman. It feels tacky and strange and the longer it persists the more I kept wondering what Seinfeld was doing with this. Why include this especially as the only form of relatively topical political humor, beyond, I guess, the depiction of business elites being complete morons? Why this? Again, it would be different if it was funny in execution, like the Saving Private Ryan D-Day parody from Sausage Party. This just isn’t funny, and its inclusion feels so odd compared to the stale nature of its other comedy.

As an admittedly silly enterprise, one that doesn’t even pretend to be accurate even as it flirts with the truth, Unfrosted is a successfully stupid comedy that feels a little too aimless, a little too edge-less and safe, and a little too dated and stale in its approach to comedy (lots of 1960s Boomer nostalgia ahoy). It’s hard to work up that much risible anger over a 90-minute movie that features a living ravioli creature. Clearly this movie wasn’t trying to be anything other than a gleefully stupid comedy, but I wanted more pep from its jokes and whimsy and general idiocy. I think the way to go may have been all the way in the other direction, treating the formation of a toaster pastry like international nuclear secrets and playing the corporate espionage completely straight while also making it patently ridiculous. Unfrosted did, however, make me want a Pop Tart that I ate afterwards, although it was my local grocery store’s generic brand, so I guess that doesn’t directly benefit Kellogg’s. This movie exists as a Seinfeld curiosity that ultimately left me hungry for more.

Nate’s Grade: C

You must be logged in to post a comment.