Blog Archives

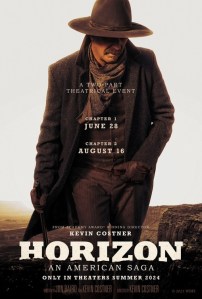

Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 (2024)

I admire Kevin Costner throwing out all the stops to achieve his passion, a four-part, twelve-hour film series to showcase a sprawling Western epic. The man put a hundred million of his own money into the first two parts of Horizon: An American Saga, and the time devoted to this project was so all-consuming that Costner quit the Yellowstone series, a cable TV juggernaut getting bigger ratings every season. It’s ballsy all right, to abandon a monumentally successful series at the height of its zeitgeist popularity so he can direct not just one but four throwback Westerns that will ultimately be as long as the Lord of the Rings trilogy. It’s rare to see this level of sheer chutzpah in Hollywood. Horizon’s first part was released in June, with its completed second part intended to be released a mere two months later in August. After the poor box-office of Part One, the studio decided to pull Part Two from the release schedule, ostensibly to give people more time to catch the first movie. Will we ever see Part Two in theaters? Will we ever see Part Three, which Costner is currently filming, or Part Four, which Costner is currently raising money for? Costner intended to release the whole saga as a miniseries upon completion, and this might be the best case scenario. As a movie, albeit one quarter of an intended whole, Horizon Part One feels far more structured as an incomplete and rather prosaic TV series.

Upon the completion of the 170 minutes, I was left wondering what was here that would make someone want to come back for a lengthy second part, let alone a third and a fourth. It doesn’t feel like a complete movie or even a completed chapter, and again let me cite Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series. Released over the course of three years, each movie had its own form of a beginning, middle, and end, with each climaxing around some event that left one satisfied by its conclusion. They didn’t just feel like chapters linking to the next; they felt like completed stories that pushed forward a larger overall story. Now, with Horizon Part One, it doesn’t feel like a three-hour movie, rather like three one-hour episodes of a TV series. Each of those hours feels too separate from the other. I’m reminded of television in the streaming era, where producers anticipate viewers binging through multiple episodes in speedy succession. This tacit assumption lends itself toward the general pacing issues I find with too many streaming series, where the filmmakers take far too long to get things moving in a significant manner. I’m reminded of a joke by Topher Florence that back in the day a show like Surf Dracula would feature its lead character surfing in weekly adventures, but the streaming age version would take its entire first season showing how he got his surfboard and then spend five minutes surfing in the finale. When you’re pacing out only one quarter of your possible intended story, calling it slow and lacking development and payoffs is an obvious hazard, which is why every movie needs to be its own thing, to provide a sense of conclusion even if it’s not the final conclusion.

Part One is divided into three parts: 1) the early settlers of Horizon, in the San Pedro Valley, being massacred by the Apache, 2) an old gunslinger (Kevin Costner) tasked with protecting a woman and child on the run from vengeful gunmen, 3) a wagon train of settlers headed to Horizon. Now, from that very streamlined synopsis, which of those storylines sounds the most exciting? Which of those storylines sounds like it can lend itself toward having an in-movie climax? Which of these storylines feels the most fraught with danger and intrigue? It’s the one starring Costner himself, of course, fitting naturally into the role of a tough curmudgeon.

I’m confused why the entire first hour of this movie is devoted to following the frontier town when we’re only going to get two survivors total that go forward. As far as its narrative importance, this entire section could have been condensed to a terrifying flashback from Frances Kittredge (Sienna Miller) and her daughter after the fact. The majority of this hour is spent watching the fine Christian folk of the early days of Horizon die horribly. We’re confined inside the battered Kittredge home that serves as the foundation of a siege thriller, with the band of various townspeople trapped and trying to fight off their indigenous intruders. The attack is prolonged and unsparing in its violence, eliminating all these nice, smiling faces from before. What does it add up to? It’s the tragic back-story for Frances, but it also makes her conveniently romantically unattached so that the nice cavalryman, Trent Gephart (Sam Worthington), can swoon and she can Learn to Love Again. It also sets up a young Apache warrior, Pionsenay (Owen Crow Shoe), making aggressive moves that his elders disagree with in their continued efforts to find some balance with the American settlers grabbing their territory. It also sets up what serves as the only possible character arc completion, with young Russell (Etienne Kellici) escaping the massacre in the beginning to then witness a massacre of Apache, and as he observes the scalping butchery, it galls him, not providing the relief of vengeance he had sought. Now that’s a conceivably emotional storyline, but Russell isn’t the primary character, or even one of the most essential supporting characters. You might genuinely forget about him like I did.

Something else I forgot an hour in was that Part One opens with Ellen Harvey (Jena Malone) shooting her abusive husband and running out. This prologue eventually comes back to setting up the present-day conflicts of the second hour, where Ellen has started a new life as Lucy with her young son. She lives in the Wyoming territory with a prostitute, Marigold (Abbey Lee). This storyline picks up significantly with new characters coming into the mix and disrupting the status quo. The first is Hayes Ellison (Costner) who finds himself attracted to Marigold, perhaps recognizing a woman in over her head. The second are the Sykes brothers (Jamie Campebell Bower, Jon Beavers) who have come looking to retrieve Lucy and her child, the son of their dearly departed pa who was slain in the opening. I am astounded that Costner decided to make the audience wait an hour for this segment because it feels like a much better fit to open Part One. There’s an immediacy to the looming danger and the consequences of actions, and what would serve as the Act One break is when Hayes has to intervene at great risk. This is, by far, the best segment of Horizon Part One. The ensuing on-the-run segment doesn’t get much further, setting up ongoing antagonism between the two sides that presumably will come to blows again. It’s not exactly reinventing the wagon wheel here: drifter reluctantly becoming protector for the vulnerable and reckoning with his shady past and trying to make amends. However, for this first movie, at least this storyline provides a sustained level of engagement with needed urgency.

The weakest portion is the wagon train led by Matthew Van Weyden (Luke Wilson). The most significant conflict during this section isn’t even the protection of the wagon train, it’s whether or not the hoity-toity British couple (Tom Payne, Anna and the Apocalypse‘s Ella Hunt) will assimilate to life on the prairie. They’re privileged, though at least he seems to recognize this. She bathes in the drinking water supply in an extended sponge bath sequence that feels so oddly gratuitous and leery. Two scouts are caught eagerly peeping and this seems like the most significant conflict of this whole section. They’re headed for Horizon, the setting of tragedy and indigenous conflict we know, but the entire wagon train lacks any feeling of dread or even the opposite, a feeling of yearning for a new life. It’s just a literal pileup of underwritten characters in movement without giving us a reason to care.

Costner’s Western eschews the trappings of modern revisionism, deconstructing the heroism and Manifest Destiny mythology of popular Wild West media. This isn’t a deconstruction but a full blown romantic classical Western, embracing the tropes with stone-faced gusto. In some ways it feels like Costner’s version of a Taylor Sheridan show (1883, Yellowstone). He left a Sheridan show to make his own Sheridan show. It’s more measured in its portrayal of the Native Americans even as it shows them massacring men, women, and children as our first impression. I wager Costner is showing that the evils of violent tendencies pervade both sides of the conflict, with a troop of American scalp-hunters that don’t really care where those scalps come from. It’s hard to fully articulate the themes given this is only one-fourth of the overall intended picture. The expansive settings are stunning and gorgeously filmed. I can understand why Costner would want people to watch this movie on the big screen with scenery this beautiful from cinematographer J. Michael Muro, who served as Costner’s DP on 2003’s Open Range, another muscular Western. Fun fact: Muro also served as a Steadicam operator on Costner’s Best Picture-winning Dances with Wolves, so their professional relationship goes back thirty-five years and covers Costner’s love affair with Westerns.

During its conclusion, Horizon: An American Saga runs through a wordless montage of clips that serves as a trailer for the forthcoming Part Two. It’s not edited like a trailer, more so a very leisurely preview with clips that look good but, absent context, can be shrug-worthy. Oh look, a character looking out a window pensively. Oh look, a character walking along a trail. Oh look, a character dismounting from a horse. Oh look, another character looking out a window pensively. It’s hard for me to fathom this truncated preview getting too many people excited for what Part Two has to offer, but then I think that’s the same problem with Part One. It doesn’t serve as a grabber, with characters we really care about, with conflicts that keep us glued, and with revelations and character turns that can keep us intrigued and desperately wanting more. It’s hard for me to think of that many people walking out of Part One and being ravenous for nine more hours. I accept that stories might feel incomplete and characters might feel disjointed, but Horizon is perhaps a Western best left in the distance, at least until you can binge it in its completed form, whatever that may be, though I doubt we’re going to get four full movies. Ultimately, Costner’s opus will need to be judged as a whole rather than as consecutive parts.

Nate’s Grade: C

Love Lies Bleeding (2024)

With 2019’s Saint Maud, writer/director Rose Glass made her mark in the realm of religious horror, but it wasn’t just a high caliber boo-movie, it was an artistic statement on isolation, on obsession, and with stunning visuals to make the movie stand out even more. Next up, Glass has set her sights on a similar tale of isolation and obsession, in the realm of film noir.

With 2019’s Saint Maud, writer/director Rose Glass made her mark in the realm of religious horror, but it wasn’t just a high caliber boo-movie, it was an artistic statement on isolation, on obsession, and with stunning visuals to make the movie stand out even more. Next up, Glass has set her sights on a similar tale of isolation and obsession, in the realm of film noir.

In 1989, Lou (Kristen Stewart) works as the manager of a small gym in the American Southwest. She spots Jackie (Katy O’Brian) passing through on her way to a bodybuilding competition in Las Vegas. Together, the two women form a passionate relationship and are transfixed over one another, but in order to keep the good times rolling, each will be required to commit more desperate acts, including body removal and keeping secrets from Lou’s estranged father, Lou Senior (Ed Harris), a shooting range owner who operates as a cartel gun runner.

Love Lies Bleeding powers along like a runaway locomotive, a genre picture awash in the lurid and sundry language of film noir with a queer twist, until it goes completely off the rails by its conclusion, a pile-up of tones and ideas that’s practically admirable even if it doesn’t come together. Until that final act, what we’re given is a contemporary film noir escapade following desperate and obsessive people get completely well over their heads into danger. Reminiscent of the Wachowski’s Bound, we have a film noir that lets the ladies have all the fun playing into the tropes of the sultry femme fatales, and in this movie, both the lead characters are their own femme fatales and ingenues. Lou is the one who pushes steroid use onto Jackie, who resists at first and wants to go about building her body the old-fashioned way. Lou is also the one with the shady past and connections that come calling back at the worst time. Once fully hooked on her diet of steroids, Jackie becomes increasingly more unpredictable and desperate, leaving Lou to try and clean up their accumulating messes. They both use the other, they both enable the other, and they both project what they want onto the other even after their collective screw-ups. It’s a self-destructive partnership but neither can see through the haze of desire. They see one another as an escape, when really it’s an unraveling of self (though I suppose one could argue “living your best self,” already a subjective claim, could include being a genuine garbage human). In a way, this is a relationship that’s all rampant desire and unfulfilled consumption, and it leaves both parties always wanting more. It’s a bad romance with bad people doing bad things badly, and if that isn’t a tidy summation of most film noir, then I don’t know what is.

Love Lies Bleeding powers along like a runaway locomotive, a genre picture awash in the lurid and sundry language of film noir with a queer twist, until it goes completely off the rails by its conclusion, a pile-up of tones and ideas that’s practically admirable even if it doesn’t come together. Until that final act, what we’re given is a contemporary film noir escapade following desperate and obsessive people get completely well over their heads into danger. Reminiscent of the Wachowski’s Bound, we have a film noir that lets the ladies have all the fun playing into the tropes of the sultry femme fatales, and in this movie, both the lead characters are their own femme fatales and ingenues. Lou is the one who pushes steroid use onto Jackie, who resists at first and wants to go about building her body the old-fashioned way. Lou is also the one with the shady past and connections that come calling back at the worst time. Once fully hooked on her diet of steroids, Jackie becomes increasingly more unpredictable and desperate, leaving Lou to try and clean up their accumulating messes. They both use the other, they both enable the other, and they both project what they want onto the other even after their collective screw-ups. It’s a self-destructive partnership but neither can see through the haze of desire. They see one another as an escape, when really it’s an unraveling of self (though I suppose one could argue “living your best self,” already a subjective claim, could include being a genuine garbage human). In a way, this is a relationship that’s all rampant desire and unfulfilled consumption, and it leaves both parties always wanting more. It’s a bad romance with bad people doing bad things badly, and if that isn’t a tidy summation of most film noir, then I don’t know what is.

For the first hour, I was right onboard with the movie and its grimy atmosphere. The plot has a clear acceleration point, though the first twenty minutes is also given to some cheap “who-slept-with-who-before-they-knew-who” drama that I was instantly ready to put behind. However, once the climactic death hangs over our two lovers, there’s an immediate sense of danger that makes every scene evoke the gnawing desperation of our characters. The screenplay by Maud and Weronika Tofilska has such a deliberate cause-effect construction, and no film noir would be complete without the loose ends the characters would have to fret over. What also helps to elevate the immersion is the electric chemistry between Stewart (Spencer) and O’Brian (The Mandalorian), who worked previously in the world of women’s body building and clearly felt a kinship with this role, and she is also a born movie star. The two women are great together, enough so that the audience might start believing that these two lost souls are actually good for one another. We too might get seduced by the possibility that everything will turn out for the better, when we all know that’s not how film noir goes. I will say there are some gutsy decisions toward the end that will test audiences with their loyalty to our couple, but most felt completely in character even if their lingering impact is for you to reel back, hold your breath, and then heavily sigh.

It would also be impossible to discuss the movie without discussing just how overwhelmingly carnal it can be. I recently reviewed Drive-Away Dolls and noted how horny this lesbian sex comedy road trip was, though to me it felt empty and exploitative. With Love Lies Bleeding, the desire of these two women, and their mutual fulfillment, serves as another drug for them to mainline and then abuse. There is a hanger to the film’s gaze that is effective without feeling overly leering. The body building aspect puts a more natural fixation on lingering on the muscles and curves of human forms, and how Jackie is intending to transform herself into a fantasy version. The sexual content begins to ebb as soon as the murder content ramps up.

It would also be impossible to discuss the movie without discussing just how overwhelmingly carnal it can be. I recently reviewed Drive-Away Dolls and noted how horny this lesbian sex comedy road trip was, though to me it felt empty and exploitative. With Love Lies Bleeding, the desire of these two women, and their mutual fulfillment, serves as another drug for them to mainline and then abuse. There is a hanger to the film’s gaze that is effective without feeling overly leering. The body building aspect puts a more natural fixation on lingering on the muscles and curves of human forms, and how Jackie is intending to transform herself into a fantasy version. The sexual content begins to ebb as soon as the murder content ramps up.

Unfortunately, for a movie that gets by on some big artistic chances, not all of them work, and most of the miscues hamper the final thirty minutes. In the final act, Jackie abandons Lou and goes off on her own to her Las Vegas bodybuilding competition, and at that point it’s like she’s in a completely different kind of movie. Hers is a movie about drug addiction and hitting a wall, as she has some very public freakouts and hallucinations. Although from there, Love Lies Bleeding indulges in some peculiar imagery that emphasizes the extreme bulging muscles of Jackie like she was the Hulk. While the movie never presents these flights of fancy as magic realism meant to be taken literally, the sheer goofiness of these moments and imagery can hamper moments, especially during a climactic showdown that feels more like someone’s kinky dream. Ultimately, I don’t think the characters of Lou or Jackie are that interesting. Lou’s criminal past was deserving of more attention far earlier, and Jackie is so narrowly-focused that every scene with her after a certain point is only going to reinforce the same obsessive drive and perspective. Like other genres, film noir works with archetypes, and Love Lies Bleeding isn’t re-inventing the genre, merely giving it a very specific sapphic spin, set amidst the haze of the go-go 1980s.

Rose Glass is a hell of an intriguing filmmaker after two very different movies in two very different genres, both of which have been defined for decades by male filmmakers. This woman is a natural filmmaker with clear vision, and even through the bumps, you know you’re in good hands here with a storyteller that’s going to take you places. The cinematography is fluid and grimy to the point where you may feel the need to take a shower afterwards. Everything seems coated with dirt and sweat. The synth-heavy musical score accommodates rather than overwhelms. The performances are strong throughout, and the screenplay choices, while not always working out, are bold and in-character. Love Lies Bleeding provides just about everything you could want from a lesbian bodybuilder film noir thriller, a movie that recognizes the sizzle of its genre elements and makes grand, scuzzy use. At this point, we should all be paying attention to whatever Glass wants to do next as a filmmaker. It might not be perfect, it might not even work, but it will certainly demand our attention and time.

Nate’s Grade: B

Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire (2023)

Creating an original sci-fi/fantasy universe is hard work. It involves bringing to life an entire new universe of characters, worlds, back-stories, rules, conflicts, cultures, and classes. There’s a reason major studios look to scoop already established creative universes rather than build their own from scratch. This is what director Zack Snyder had in mind when he pitched a darker, grittier, more mature Star Wars to Disney, who passed. Over the ensuing decade, Snyder and his collaborators, Shay Hatten and Kurt Johnstad, continued working on their concept, transforming it into an original movie series, resulting in Netflix’s big-budget holiday release, Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire, a clunky title I will not be retyping in full again. Snyder’s original results of the “darker, grittier Star Wars” are rather underwhelming and don’t make me excited for the concluding second movie being released in April. Why go to the trouble of building your own universe if you don’t want to fill in the details about what makes it important or at least even unique? I can see why Snyder would have preferred Rebel Moon as a Star Wars pitch, because they could attach all the established world-building from George Lucas and his creative collaborators as a quick cheat code.

Creating an original sci-fi/fantasy universe is hard work. It involves bringing to life an entire new universe of characters, worlds, back-stories, rules, conflicts, cultures, and classes. There’s a reason major studios look to scoop already established creative universes rather than build their own from scratch. This is what director Zack Snyder had in mind when he pitched a darker, grittier, more mature Star Wars to Disney, who passed. Over the ensuing decade, Snyder and his collaborators, Shay Hatten and Kurt Johnstad, continued working on their concept, transforming it into an original movie series, resulting in Netflix’s big-budget holiday release, Rebel Moon – Part One: A Child of Fire, a clunky title I will not be retyping in full again. Snyder’s original results of the “darker, grittier Star Wars” are rather underwhelming and don’t make me excited for the concluding second movie being released in April. Why go to the trouble of building your own universe if you don’t want to fill in the details about what makes it important or at least even unique? I can see why Snyder would have preferred Rebel Moon as a Star Wars pitch, because they could attach all the established world-building from George Lucas and his creative collaborators as a quick cheat code.

In another galaxy, the imperial Motherworld is the power in the universe. The king and his family have been assassinated, and in the power struggle that follows, several planets have taken up arms to fight for independence. On a distant moon, Kora (Sofia Boutella) is doing her best to live a nondescript life as a farmer, helping to provide for her community and stay out of trouble. Well trouble comes knockin’ anyway with Admiral Atticus Noble (Ed Skrein) and his fleet looking for resources and powerless villagers to abuse. Kora’s history of violence comes back to her as she fights back against the Motherworld soldiers with cool precision. Her only hope is to gather a team of the most formidable warriors to protect her village from reprisals. Kora and company band together while her mysterious past will come back to haunt her reluctant return to prominence.

For the first thirty to forty minutes of Rebel Moon, I was nodding along and enjoying it well enough, at least enough to start to wonder if the tsunami of negative reviews had been unfairly harsh, and then the rest of the movie went downhill. One of the major problems of this Part One of a story is that it feels like a movie entirely made up of Act Two plotting. Once our hero sets off on her mission, the movie becomes a broken carousel of meeting the next member of the team, seeing them do something impressive as a fighter, getting some info dump about their mediocre tragic backstory, and then we’re off to the next planet to repeat the process. After the fifth time, when a character says, “Anyone else you know?” I thought that the rest of the movie, and the ensuring Part Two, would be nothing but recruiting members until every character in the galaxy had joined these ragtag revolutionaries, like it was all one elaborate practical joke by Snyder. Some part of me may still be watching Rebel Moon, my eyes glazing over while we add the eight hundred and sixty-sixth person who is strong but also shoots guns real good. Then the movie manufactures an ending that isn’t really an ending, merely a pause point, but without any larger revelations or escalations to further our anticipation for Part Two in four months’ time. What good are these handful of warriors going to be defending a village in a sci-fi universe where the bad guys could just nuke the planet from orbit? Find out in April 2024, folks!

For the first thirty to forty minutes of Rebel Moon, I was nodding along and enjoying it well enough, at least enough to start to wonder if the tsunami of negative reviews had been unfairly harsh, and then the rest of the movie went downhill. One of the major problems of this Part One of a story is that it feels like a movie entirely made up of Act Two plotting. Once our hero sets off on her mission, the movie becomes a broken carousel of meeting the next member of the team, seeing them do something impressive as a fighter, getting some info dump about their mediocre tragic backstory, and then we’re off to the next planet to repeat the process. After the fifth time, when a character says, “Anyone else you know?” I thought that the rest of the movie, and the ensuring Part Two, would be nothing but recruiting members until every character in the galaxy had joined these ragtag revolutionaries, like it was all one elaborate practical joke by Snyder. Some part of me may still be watching Rebel Moon, my eyes glazing over while we add the eight hundred and sixty-sixth person who is strong but also shoots guns real good. Then the movie manufactures an ending that isn’t really an ending, merely a pause point, but without any larger revelations or escalations to further our anticipation for Part Two in four months’ time. What good are these handful of warriors going to be defending a village in a sci-fi universe where the bad guys could just nuke the planet from orbit? Find out in April 2024, folks!

The entire 124-minute enterprise feels not just like an incomplete movie but an incomplete idea. This is because the influences are obvious and copious for Snyder. Rebel Moon starts feeling entirely like Star Wars, but then it very much becomes a space opera version of The Magnificent Seven, itself a remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai. With our humble farmer, our high plains drifter trying to turn their back on an old life of violence, and the recruitment of our noble fighters to ward off the evil bandits coming to harass this small outpost, it’s clearly The Magnificent Seven, except Snyder doesn’t provide us the necessary material to invest in this scrappy team. The characters are all different variations of the same stoic badass archetype, like you took one character mold and simply sliced it into ten little shear pieces. The characters don’t even have the most basic difference you could offer in an action movie, variation in skill and weapons. One lady has laser swords (a.k.a. lens flair makers) but pretty much everyone else is just the same heavy gun fighter. One guy doesn’t even bother to put on a shirt. Some of them are slightly bigger or more slender than others but the whole get-the-gang-together plot only really works if we have interesting characters. If we don’t like the prospective team members, it’s like we’re stuck in an endless job interview with only lousy candidates.

The fact that Rebel Moon is derivative is not in itself damaging. Science fiction is often the sum of its many earlier influences, including Star Wars. Rebel Moon cannot transcend its many film influences because it fails to reform them into something coherent of its own. There is no internal logic or connection within this new universe. The original world building amounts to a slain royal family, an evil fascist regime, and maybe a magic princess connected to a prophecy of balance, and that’s it. All the flashbacks and expository data dumps fail to create a clearer, larger picture of how this sci-fi universe operates. The inner workings are kept so broad and abstract. We have an imperial evil and assorted good-hearted little guys. The movie begins by introducing a robot clan of knights that are dying out, and even a young Motherworld soldier who seems likely to defect, both opportunities to go into greater character detail and open up this world and its complications. So what does Snyder do? He leaves both behind shortly. Even though we visit a half dozen planets, these alien worlds don’t feel connected, as if Snyder just told concept artists to follow whatever whim they had. They don’t even feel that interesting as places. One of them is desert. One of them has a saloon. One of them is a mining planet. It’s like the worlds have been procedurally generated from a computer for all we learn about them. They’re just glorified painted backdrops that don’t compliment the already shaky world building. They’re too interchangeable for all the impact on the plot and characters and any declining sense of wonder.

The fact that Rebel Moon is derivative is not in itself damaging. Science fiction is often the sum of its many earlier influences, including Star Wars. Rebel Moon cannot transcend its many film influences because it fails to reform them into something coherent of its own. There is no internal logic or connection within this new universe. The original world building amounts to a slain royal family, an evil fascist regime, and maybe a magic princess connected to a prophecy of balance, and that’s it. All the flashbacks and expository data dumps fail to create a clearer, larger picture of how this sci-fi universe operates. The inner workings are kept so broad and abstract. We have an imperial evil and assorted good-hearted little guys. The movie begins by introducing a robot clan of knights that are dying out, and even a young Motherworld soldier who seems likely to defect, both opportunities to go into greater character detail and open up this world and its complications. So what does Snyder do? He leaves both behind shortly. Even though we visit a half dozen planets, these alien worlds don’t feel connected, as if Snyder just told concept artists to follow whatever whim they had. They don’t even feel that interesting as places. One of them is desert. One of them has a saloon. One of them is a mining planet. It’s like the worlds have been procedurally generated from a computer for all we learn about them. They’re just glorified painted backdrops that don’t compliment the already shaky world building. They’re too interchangeable for all the impact on the plot and characters and any declining sense of wonder.

Given the open parameters of imagination with inventing your own sci-fi/fantasy universe, I am deeply confused by some of the choices that Snyder makes that visually weigh down this movie in anachronistic acts of self-sabotage. Firstly, the villains are clearly meant to be a one-to-one obvious analog for the Empire in Star Wars, itself an analog for the fascists of World War II, but Lucas decided having them as stand-ins was good enough without literally having them dress in the same style of uniforms as the literal fascists from World War II. You have an interconnected galaxy of future alien cultures and the bad guys dress like they stepped out of The Man in the High Castle. It’s too familiar while being too specific, and the fact that it’s also completely transparent with its iconic source references is yet another failure of imagination and subtext. I just accepted that the Space Nazis were going to look like literal Nazis, but what broke my brain was the costuming of Skrein’s big baddie in the second half of the movie. At some point he changes into a white dress shirt with a long thin black tie and all I could think about was that our space opera villain looks like one of those door-to-door Mormon missionaries (“Hello, have you heard the Good Word of [whatever Snyder is calling The Force in this universe]?”). Every scene with this outfit ripped me out of the movie; it was like someone had photo-shopped a character from a different movie. It certainly didn’t make the devious character of Atticus Noble more threatening or even interesting. I view this entire creative decision as a microcosm for Rebel Moon: a confused fusion of the literal, the derivative, and the dissonant.

Snyder is still a premiere visual stylist so even at its worst Rebel Moon can still be an arresting watch. He’s one of the best at realizing the awe of selecting the right combination of images, a man who creates living comic book splash pages. I realized midway through Rebel Moon why the action just wasn’t as exciting for me. There’s a decided lack of weight. It’s not just that scenes don’t feel well choreographed or developed to make use of geography, mini-goals, and organic complications, the hallmarks of great action, it’s that too little feels concrete. It feels too phony. I’m not condemning the special effects, which are mostly fine. The action amounts to Character A shoots at Bad Guy and Character B shoots at Other Bad Guy, maybe behind some cover. There’s only one sequence that brings in specifics to its action, with the challenge of defeating a rotating turret gun pinning the team down from escape. That sequence established a specific obstacle and stakes. It worked, and it presented one of the only challenges that wasn’t immediately overcome by our heroes.

Snyder is still a premiere visual stylist so even at its worst Rebel Moon can still be an arresting watch. He’s one of the best at realizing the awe of selecting the right combination of images, a man who creates living comic book splash pages. I realized midway through Rebel Moon why the action just wasn’t as exciting for me. There’s a decided lack of weight. It’s not just that scenes don’t feel well choreographed or developed to make use of geography, mini-goals, and organic complications, the hallmarks of great action, it’s that too little feels concrete. It feels too phony. I’m not condemning the special effects, which are mostly fine. The action amounts to Character A shoots at Bad Guy and Character B shoots at Other Bad Guy, maybe behind some cover. There’s only one sequence that brings in specifics to its action, with the challenge of defeating a rotating turret gun pinning the team down from escape. That sequence established a specific obstacle and stakes. It worked, and it presented one of the only challenges that wasn’t immediately overcome by our heroes.

The Snyder action signature of slow-mo ramps has long ago entered into self-parody territory (I’m convinced a full hour of his four-hour Justice League cut was slow motion), so its use has to be even more self-aware here, especially in quizzical contexts. There are moments where it accentuates the visceral appeal of the vivid imagery, like a man leaping atop the back of a flying griffin, akin to an 80s metal album cover come to life. Then there are other times that just leave you questioning why Snyder decided to slow things down… for this? One such example is where a spaceship enters the atmosphere in the first twenty minutes, and a character drops their seeds in alarm, and those seeds falling are detailed in loving slow motion. Why show a character’s face to impart an emotion when you can instead see things falling onto the ground so dramatically?

The actors are given little to do other than strike poses and attitudes, and for that they all do a fine job of making themselves available for stills and posters and trailers. Boutella (The Mummy) is good at being a stoic badass. I just wish there was something memorable for her to do or make use of her athleticism. The best actor in the movie is Skrein (Deadpool) who really relishes being a smarmy villain. He’s not an interesting bad guy but Skrein at least makes him worth watching even when he’s in the most ridiculous outfit and awful Hitler youth haircut. There’s also Jena Malone (Sucker Punch) as a widowed spider-woman creature. So there’s that. Cleopatra Coleman (Dopesick), who plays one half of a revolutionary set of siblings along with Ray Fisher, sounds remarkably like Jennifer Garner. Close your eyes when she’s speaking, dear reader, and test for yourself. I was most interested in Anthony Hopkins as the voice of our malfunctioning android (literally named “Jimmy the Robot”) operating on mysterious programming that hints at something larger in place relating to perhaps the princess being alive. Fun fact: Rebel Moon features both actors who played the role of Daario on Game of Thrones (Skrien and Michiel Husiman).

The actors are given little to do other than strike poses and attitudes, and for that they all do a fine job of making themselves available for stills and posters and trailers. Boutella (The Mummy) is good at being a stoic badass. I just wish there was something memorable for her to do or make use of her athleticism. The best actor in the movie is Skrein (Deadpool) who really relishes being a smarmy villain. He’s not an interesting bad guy but Skrein at least makes him worth watching even when he’s in the most ridiculous outfit and awful Hitler youth haircut. There’s also Jena Malone (Sucker Punch) as a widowed spider-woman creature. So there’s that. Cleopatra Coleman (Dopesick), who plays one half of a revolutionary set of siblings along with Ray Fisher, sounds remarkably like Jennifer Garner. Close your eyes when she’s speaking, dear reader, and test for yourself. I was most interested in Anthony Hopkins as the voice of our malfunctioning android (literally named “Jimmy the Robot”) operating on mysterious programming that hints at something larger in place relating to perhaps the princess being alive. Fun fact: Rebel Moon features both actors who played the role of Daario on Game of Thrones (Skrien and Michiel Husiman).

Even with all the money at Netflix’s mighty disposal, Rebel Moon can’t make up for its paltry imagination and thus feels like an empty enterprise. I’m reminded of 2011’s Sucker Punch, the last time Snyder was left completely to his own devices. I wrote back then, “Expect nothing more than top-of-the-line eye candy. Expect nothing to make sense. Expect nothing to really matter. In fact, go in expecting nothing but a two-hour ogling session, because that’s the aim of the film. Look at all those shiny things and pretty ladies, gentlemen.” That assessment seems fitting for Rebel Moon as well, a movie that can’t be bothered to provide compelling characters, drama, or world-building to invest in over two to four hours, once you consider the approaching Part Two. I wish this movie had a more distinct vision and sense of humor, something akin to Luc Besson’s lively Fifth Element, but fun is not allowed in the Zack Snyder universe, so everything must be grim, because grim means mature, and mature means automatically better, right? Rebel Moon is a space opera where you’ll prefer the void.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Cold Mountain (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released December 25, 2003:

Premise: At the end of the Civil War, Inman (Jude Law, scruffy) deserts the Confederate lines to journey back home to Ada (Nicole Kidman), the love of his life he’s spent a combined 10 minutes with.

Results: Terribly uneven, Cold Mountain‘s drama is shackled by a love story that doesn’t register the faintest of heartbeats. Kidman is wildly miscast, as she was in The Human Stain, and her beauty betrays her character. She also can’t really do a Southern accent to save her life (I’m starting to believe the only accent she can do is faux British). Law’s ever-changing beard is even more interesting than her prissy character. Renee Zellweger, as a no-nonsense Ma Clampett get-your-hands-dirty type, is a breath of fresh air in an overly stuffy film; however, her acting is quite transparent in an, “Aw sucks, give me one ‘dem Oscars, ya’ll” way.

Nate’’s Grade: C

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I kept meaning to come back to Cold Mountain, a prototypical awards bait kind of movie that never really materialized, but one woman ensured that it would be on my re-watch list for 2003. My wife’s good friend, Abby, was eager to hear my initial thoughts on the movie when I wrote my original review at the age of twenty-one. This is because Cold Mountain is a movie that has stayed with her for the very fact that her grandfather took her to see it when she was only nine years old. While watching, it dawned on nine-year-old Abby that this was not a movie for nine-year-olds, and it’s stuck with her ever since. I think many of us can relate to watching a movie with our parents or family members that unexpectedly made us uncomfortable. For me, it was Species, where I was 13 years old and the movie was about a lady alien trying to procreate. I think my father was happy that I had reached an acceptable age to go see more R-rated movies in theaters. Social media has been awash lately with videos of festive families reacting to the shock value of Saltburn with grumbles and comical discomfort (my advice: don’t watch that movie with your parents). So, Abby, this review is for you, but it’s also, in spirit, for all the Abbys out there accidentally exposed to the adult world uncomfortably in the company of one’s parents or extended family.

Cold Mountain succumbs to the adaptation process of trying to squeeze author Charles Frazier’s 1997 book of the same name into a functional movie structure, but the results, even at 150 minutes, are unwieldy and episodic, arguing for the sake of a wider canvas to do better justice to all the themes and people and minor stories that Frazier had in mind. Director Anthony Minghella’s adaptation hops from protagonist to protagonist, from Inman to Ada, like perspectives for chapters, but there are entirely too many chapters to make this movie feel more like a highly diluted miniseries scrambling to fit all its intended story beats and people into an awards-acceptable running time. This is a star-studded movie, the appeal likely being working with an Oscar-winning filmmaker (1996’s The English Patient) of sweep and scope and with such highly regarded source material, a National Book Award winner. The entire description of Cold Mountain, on paper, sounds like a surefire Oscar smash for Harvey Weisntein to crow over. Yet it was nominated for seven Academy Awards but not Best Picture, and it only eventually won a single Oscar, deservedly for Renee Zellweger. I think the rather muted response to this Oscar bait movie, and its blip in a lasting cultural legacy, is chiefly at how almost comically episodic the entire enterprise feels. This isn’t a bad movie by any means, and quite often a stirring one, but it’s also proof that Cold Mountain could have made a really great miniseries.

The leading story follows a disillusioned Confederate defector, Inman (Jude Law), desperately trying to get back home to reunite with his sworn sweetheart, Ada (Nicole Kidman), who is struggling mightily to maintain her family’s farm after the death of her father. That’s our framework, establishing Inman as a Civil War version of Odysseus fighting against the fates to return home. Along the way he surely encounters a lot of famous faces and they include, deep breath here, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Natalie Portman, Giovanni Ribisi, Cillian Murphy, Eileen Atkins, Taryn Manning, Melora Walters, Lucas Black, and Jena Malone. Then on Ada’s side of things we have Zellweger, Donald Sutherland, a villainous Ray Winstone, Brendan Gleeson, Charlie Hunam, Kathy Baker, Ethan Suplee, musician Jack White, and Emily Descehanel, and this is the storyline that stays put in the community of Cold Mountain, North Carolina.

That is a mountain of stars, and with only 150 minutes, the uneven results can feel like one of those big shambling movies from the 1950s that have dozens of famous actors step on and as quickly step off the ride. Poor Jena Malone (Rebel Moon) appears as a ferry lady and literally within seconds of offering to prostitute herself she is shot dead and falls into the river (well, thanks for stopping by Jena Malone, please enjoy your parting gift of this handsome check from Miramax). Reducing these actors and the characters they are playing down to their essence means we get, at most, maybe 10-15 minutes with them and storylines that could have been explored in richer detail. Take Portman’s character, a widowed mother with a baby trying to eke out a living, one of many such fates when life had to continue after the men ran to war for misbegotten glory. She looks at Inman with desperate hunger, but it’s not exactly lust, it’s more human connection. When she requests that Inman share her bed, it’s just to feel another warm presence beside her, someone that can hold her while she weeps about the doomed fate of her husband and likely herself. There’s a strong character here but she’s only one stop on our expedited tour. The same with Hoffman’s hedonistic priest, a man introduced by throwing the body of a slave woman he impregnated over a ridge, which might be the darkest incidental moment of the whole movie. His character is played as comic relief, a loquacious man of God who cannot resist the pleasures of the flesh, but even he comes and goes like the rest of our litany of very special guest stars. They feel more like ideas than characters.

This is a shame because there are some fantastic scenes and moments that elevate Cold Mountain. The opening Civil War battle is an interesting and largely forgotten (sorry Civil War buffs) battle that begins with a massive surprise attack that produces a colossal explosion and crater and turns into a hellish nightmare. Granted, the movie wants us to sympathize with the Confederates who were bamboozled by the Yankee explosives buried under their lines, and no thank you. The demise of Hoffman’s character comes when he and Inman are captured and join a chain gang, and they try running up a hill to get free from approaching Union troops. The Confederates shoot at the fleeing men, eventually only with Inman left, who struggles to move forward with the weight of all these dead men attached to him. When they start rolling down the hill, it becomes a deeply macabre and symbolic struggle. The stretch with Portman (May December) is tender until it goes into histrionics, with her literal baby being threatened out in the cold by a trio of desperate and starving Union soldiers (one of which played by Cillian Murphy). It’s a harrowing scene that reminds us about the sad degradation of war that entangles many innocents and always spills over from its desired targets. However, this theme that the war and what it wrought is sheer misery is one Minghella goes to again and again, but without better characterization with more time for nuance, it feels like each character and moment is meant to serve as another supporting detail in an already well-proven thesis of “war is hell.”

Even though I had previously watched the movie back in 2003, I was hoping that after two hours of striving to reunite, that Inman and Ada would finally get together and realize, “Oh, we don’t actually like each other that much,” that their romance was more a quick infatuation before the war, that both had overly romanticized this beginning and projected much more onto it from the years apart, and now that they were back together with the actual person, not their idealized imaginative version, they realized what little they had in common or knew about each other. It would have been a well-played subversion, but it also would have been a welcomed shakeup to the Oscar-bait romantic drama of history. Surely this had to be an inconvenient reality for many, especially considering that the men returning from war, the few that did, were often not the same foolhardy young men who leapt for battle.

Zellweger (Judy) was nominated for Best Actress in the preceding two years, for 2001’s Bridget Jones Diary and 2002’s Chicago, which likely greased the runway for her Supporting Actress win from Cold Mountain. There is little subtlety about her “aw shucks” homespun performance but by the time she shows up, almost fifty minutes into the movie, she is such a brash and sassy relief that I doubt anyone would care. She’s the savior of the Cold Mountain farm, and she’s also the savior of the flagging Ada storyline. Pity Ada who was raised to be a nice dutiful wife and eventual mother but never taught practical life skills and agricultural methods. Still, watching this woman fail at farming will only hold your attention for so long. Zellweger is a hoot and the spitfire of the movie, and she even has a nicely rewarding reconciliation with her besotted old man, played by Brendan Gleeson, doing his own fiddlin’ as an accomplished violin player. As good as Zellweger is in this movie is exactly how equally bad Kidman’s performance is. Her Southern accent is woeful and she cannot help but feel adrift, but maybe that’s just her channeling Ada’s beleaguered plight.

I think there’s an extra layer of entertainment if you view Inman’s journey in league with Odysseus; there’s the dinner that ends up being a trap, the line of suitors trying to steal Ada’s home and hand in the form of the duplicitous Home League boys, Hoffman’s character feels like a lotus eater of the first order, and I suppose one reading could have Portman’s character as the lovesick Calypso. Also, apparently Cold Mountain was turned into an opera in 2015 from the Sante Fe Opera company. You can listen here but I’m not going to pretend I know the difference between good and bad opera. It’s all just forceful shouting to my clumsy ears.

Miramax spent $80 million on Cold Mountain, its most expensive movie until the very next year with 2004’s The Aviator. Miramax was sold in 2010 and had years earlier ceased to be the little studio that roared so mighty during many awards seasons. I think Cold Mountain wasn’t the nail in the coffin for the company but a sign of things to come, the chase for more Oscars and increasingly surging budgets lead the independent film distributor astray from its original mission of being an alternative to the major studio system. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, it had simply become another studio operating from the same playbook. Minghella spent three years bringing Cold Mountain to the big screen, including a full year editing, and only directed one other movie afterwards, 2006’s Breaking and Entering, a middling drama that was his third straight collaboration with Law. Minghella died in 2008 at the still too young age of 54. He never lived to fully appreciate the real legacy of Cold Mountain: making Abby and her grandfather uncomfortable in a theater. If it’s any consolation to you, Abby, I almost engineered my own moment trying to re-watch this movie and having to pause more than once during the sex scene because my two children wanted to keep intruding into the room. At least I had the luxury of a pause button.

Re-View Grade: B-

Antebellum (2020)

Antebellum was originally supposed to come out in the spring and yet it only feels even more relevant today in the wake of months of protests over police brutality, the removal of Confederate monuments, and whether or not black Americans can attain justice in an imperfect system. Antebellum has also been flagged with overly negative reviews and accusations of being just another movie that exploits the horror of slavery for cheap thrills. After having seen the movie, I feel perplexed that so many of my critical brethren could not connect with the film and its finer points on the world we lived in and the world we live in today, inextricably linked.

Eden (Janelle Monae) is an enslaved woman surviving on an eighteenth-century Southern plantation run by Captain Jasper (Jack Huston) and the mistress of the land, Elizabeth (Jena Malone). Then there’s Veronica (Monae) who looks identical to Eden and lives in modern-day. She’s an author and academic speaker on social oppression and politics. How these two women are related, as well as past and present, will be revealed over the course of 100 minutes.

Antebellum is divided almost equally into 30-minute thirds, and it’s the structure that helps to aid in its mystery while also stiffling its larger implications. The first third is watching a plantation and the horrors of slavery; however, there are clues that something strange is happening. Little touches, character responses, a tattoo that seems too eerily modern. From there, we jump forward to the next third with what appears to be the same Eden, this time as a featured academic author. From here, if your mind is similar to mine, you’re attempting to bridge this connection and uncover how the past and present have become entwined. Is Veronica experiencing a deeply felt dream? Is it time travel? That was my guess before starting the film based upon the advertisement. I thought it was going to be a story about horrible racists from America’s past kidnapping black Americans to enslave. It’s a sci-fi angle that can make the material feel fresh, as there are more things to say other than the obvious and profound statements that “Slavery was terrible,” and, “It should never be forgotten or mitigated of its horror.” I also think it would serve as a rebuttal to those who ignorantly argue, “It was so long ago, why does it still matter? Get over it.” The past, in that instance, is literally ensnaring the present and forcing citizens to relive generational trauma. It’s that final third where Antebellum reveals what it really has been all along, and it’s a surprise but it also makes sense in the world that its meant to represent, leaning into a contemptible degree of human avarice that reminded me of HBO’s Westworld. It’s a fitting revelation and, as one would expect, the final third charges into an emotional catharsis as we watch Eden/Veronica fight for her freedom at last.

However, and this is a word I can already tell I’m going back to repeatedly to qualify my reservations, once the Big Reveal is known I wish we could have spent far more time dwelling in the implications of what exactly it means. I won’t spoil what exactly that reveal is but it’s definitely something that has plenty of social and political commentary and a reflection of our modern times and the injustices that have only been further highlighted this year. It’s such an interesting angle that I almost wish the filmmakers had re-prioritized their movie. Rather than structuring to best serve a mystery with a Shyamalan-style twist, it could have had its Act Two break be its inciting incident, revealing its twist as the starting point for the real terror. As a viewer, while I enjoyed the mystery and portentous mood of the movie, it presents a potent storytelling avenue that is far more compelling than the first two-thirds, but by then it’s too late. It works as context for the behavior and setting we’ve seen, both past and present, but Antebellum strangely suffers from trying to be too clever when a more straightforward version could have better tapped into its full dramatic and political commentary potential.

I was intrigued early on and came away genuinely impressed with the technical skills of debut writer/directors Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz. The photography is often stunning and that goes for their visual compositions as well as their specific camera movements. The opening scene involves a tracking shot that starts from the front of the plantation facade, and that’s the best word, all prim and proper and beatific in appearance, before swooping behind and into the slave quarters to see the ugly reality behind that illusion. I didn’t feel like the filmmakers were simply using the backdrop of slavery as cheap genre exploitation. I felt their intentions were good. The horror of slavery isn’t downplayed but it’s also not overtly recreated just to add an easy splash of violence or terror. The movie relies more on implications, like Eden sleeping next to the plantation owner every night or an enslaved man finding his wife’s necklace in a charnel house among a scattering of ashes. The implication of the larger horror is there without having to be explicit. I’m reminded of the abrasively negative condemnations of Netflix’s Cuties insofar as people seemed to be missing obvious artistic intent. These are challenging and uncomfortable movies but movies with something to say, and Antebellum is not just a simple rehash of slavery tropes to turn black people’s historical suffering into slapdash slasher pulp.

Monae (Hidden Figures) is strong throughout and continues to build her case as a leading lady. She must register her fear in subtle ways without going into larger histrionics, but she maintains a quiet strength that keeps your eyes glued to the screen. Her time spent in the present, as the author calling out aging racist ideology, is bold and confidant and serves as a counterpoint to the woman we’ve experienced on the plantation. We know that woman is still inside Eden. Monae has a late scene set in slow-motion, with the music swelling, that simultaneously feels badass, uplifting, and like an American Valkyrie blazing against unchecked Confederate revisionism.

Antebellum is better than its reputation and offers more from an artistic standpoint than hitting the same points and rehashing the same traumas of the past. It’s a movie built around its mystery when I feel like it had much more it could have said with restructuring and more time spent after its final explanations. As a mysterious thriller, it’s tasteful, thematically involving, and technically impressive. It doesn’t even use the N-word once, which could be decried by some as unrealistic but also a sign of the filmmakers’ good faith to not merely use a shameful historical legacy for base titillation. It works as a thriller with more on its mind. However, and this is my last usage of that word, it’s that mind I was more intrigued by. Antebellum is a B-movie with A-level ambitions but a story structure that keeps it stuck as a well-polished B-movie.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Neon Demon (2016)

The prospect of a new Nicolas Winding Refn movie is akin to a trip to the dentist for me: long, painful, and full or regret over one’s life choices. The Neon Demon will not change this perception of mine. I hated this movie, and the more I think about it the more I hate it. Unlike Refn’s last film, the punishing, overwrought, and nihilistic Only God Forgives, there isn’t even a kernel of an idea of a movie here. I loathed Only God Forgives but I’ll at least credit Refn for crafting something with potential in its plot dynamics. In better hands, somebody could have done something with the setup for that movie. I don’t think anyone could work with what Refn offers in The Neon Demon because he offers nothing. That’s not entirely true. He offers pretty pictures and alluring shot compositions, bathing the screen in high-contrasting colors. What he fails to offer is a story, or characters, or any reason that this movie shouldn’t exist instead as a ten-minute short. Somebody enlighten me and tell me what exactly this vacuous and tedious art exercise offers.

The prospect of a new Nicolas Winding Refn movie is akin to a trip to the dentist for me: long, painful, and full or regret over one’s life choices. The Neon Demon will not change this perception of mine. I hated this movie, and the more I think about it the more I hate it. Unlike Refn’s last film, the punishing, overwrought, and nihilistic Only God Forgives, there isn’t even a kernel of an idea of a movie here. I loathed Only God Forgives but I’ll at least credit Refn for crafting something with potential in its plot dynamics. In better hands, somebody could have done something with the setup for that movie. I don’t think anyone could work with what Refn offers in The Neon Demon because he offers nothing. That’s not entirely true. He offers pretty pictures and alluring shot compositions, bathing the screen in high-contrasting colors. What he fails to offer is a story, or characters, or any reason that this movie shouldn’t exist instead as a ten-minute short. Somebody enlighten me and tell me what exactly this vacuous and tedious art exercise offers.

Perhaps I’m being too cruel so allow me to explain the plot. Jesse (Elle Fanning) is a 16-year-old girl fresh off the bus to L.A. She gets hired at a modeling agency and makes friends with a makeup artist, Ruby (Jena Malone), who also works in a coroner’s office beautifying corpses. Jesse quickly rises through the ranks of the modeling world because of her fresh face and youthful, pure demeanor. She makes enemies with older models (Bella Heathcote, Abbey Lee) who feel threatened by her. And Keanu Reeves plays a sleazy motel owner who sticks a knife down Jesse’s throat for fun. Or that was a dream. I think. Then there’s a confrontation that includes necrophilia, murder, and cannibalism. And even after the cannibalism the movie still goes on for another fifteen minutes!

There is not nearly enough plot or any substance to carry out Refn’s near two-hour running time, which becomes all the more obvious with one dreary, pretentious, artfully self-indulgent scene after another. There are long segments where I cannot even tell you from a literal level what is happening on screen. Is Jesse descending into madness? Is Jesse losing herself to the vanity of the industry in a heavy-handed visual metaphor? Does anything happening register with the slightest merit? Refn is possibly trying to tackle the same meandering dream logic that populates David Lynch’s more obtuse filmmaking entries, like Lost Highway and Mullholland Drive (recently voted the top film so far of the twenty-first century by the BBC). I’m not a fan of untethered David Lynch but he will at least keep things interesting. The Neon Demon is a powerfully boring enterprise in annihilating audience patience. There’s no there there.

There is not nearly enough plot or any substance to carry out Refn’s near two-hour running time, which becomes all the more obvious with one dreary, pretentious, artfully self-indulgent scene after another. There are long segments where I cannot even tell you from a literal level what is happening on screen. Is Jesse descending into madness? Is Jesse losing herself to the vanity of the industry in a heavy-handed visual metaphor? Does anything happening register with the slightest merit? Refn is possibly trying to tackle the same meandering dream logic that populates David Lynch’s more obtuse filmmaking entries, like Lost Highway and Mullholland Drive (recently voted the top film so far of the twenty-first century by the BBC). I’m not a fan of untethered David Lynch but he will at least keep things interesting. The Neon Demon is a powerfully boring enterprise in annihilating audience patience. There’s no there there.

Another problem I have with Refn’s movies is that he hangs much of his meandering on broad and obvious themes and assumes they’re revelatory. Only God Forgives was all about the pointless nature of vengeance and cyclical violence, and you felt the pointlessness with one grisly and uncomfortable moment after the next. With The Neon Demon, Refn falls back on the most general of broadsides against the fashion industry. Did you know that people working in a surface-level industry could be shallow? Did you know that young women are exploited for their beauty and then quickly cast aside? Did you know that succumbing to the appeals of vanity could be self-destructive? These are the most general themes and they are presented without able commentary. It’s like Refn thinks touching upon these shallow themes is enough substance to justify all the excesses.

This is borderline unwatchable cinema. The plot is like Showgirls without the camp but still following some of the basic plot beats. There is nothing interesting about these characters at all and that’s because they’re not people but robotic figurines at best. They’re dolls for Refn to pose and play around with his purple lights. It’s like watching two hours of somebody rearrange fancy-looking furniture. The characters are just as significant as the nearest love seat or coffee table. I’ve complained about all the empty space in Refn movies and The Neon Demon is no different. This movie is padded out exponentially to become Refn’s longest movie in his career. He cares far more about his shot compositions and cinematography than storytelling. At this point I don’t think Refn has any interest whatsoever in telling a story. He wants to construct a visually immersive film experience. The Neon Demon is little more than the misty atmosphere of the impermissible, the phantasmagorical. Refn deploys controversial imagery and plot elements but he deploys them in place of actual substance. Anybody can get a strong response by throwing in a necrophilia sex scene, but has that reaction been earned and has this moment been properly setup by careful development? Absolutely not. Things just happen.

This was also billed as Refn’s horror movie but there’s nothing genuinely terrifying, at least from an intentional standpoint. You don’t feel any sense of danger or even a sense of uncertainty until the very end, and by then the movie has meandered far too much for the horror elements and gore to have an impact beyond lazy shock value. This is a movie where pretty people stand around and then, on the turn of a dime, do something outrageous. Refn hasn’t laid the groundwork for a descent into mental instability with our lead character, which seems like the most obvious solution. I could see a Black Swan-style psychosexual story about obsession with perfection and how this blinds one woman into making a multitude of sacrifices, driving her over the edge and into murder. Black Swan was a great, often brilliant movie. Go watch Black Swan instead, folks.

This was also billed as Refn’s horror movie but there’s nothing genuinely terrifying, at least from an intentional standpoint. You don’t feel any sense of danger or even a sense of uncertainty until the very end, and by then the movie has meandered far too much for the horror elements and gore to have an impact beyond lazy shock value. This is a movie where pretty people stand around and then, on the turn of a dime, do something outrageous. Refn hasn’t laid the groundwork for a descent into mental instability with our lead character, which seems like the most obvious solution. I could see a Black Swan-style psychosexual story about obsession with perfection and how this blinds one woman into making a multitude of sacrifices, driving her over the edge and into murder. Black Swan was a great, often brilliant movie. Go watch Black Swan instead, folks.

I think I have a solution that will benefit us all, dear reader. Nicolas Winding Refn should forgo the director’s chair and devote his career to being a cinematographer. He has an alluring eye for visual compositions and a great feel for atmospheric lighting, but with each passing movie I feel the man’s disdain for narrative filmmaking. His skill set is best utilized at making pretty pictures. Get him away from directing actors. Get him away from writing stories. Have adults in charge of the other aspects that help make a movie what a movie should be. The Neon Demon is a confounding, obnoxious, obtuse, intellectually destitute and monotonous movie experience. It’s frustrating to deal with the Cult of Refn in cinematic circles because I just cannot see what they see (I liked Drive well enough). The Neon Demon is too shallow and tortuous to be an insightful commentary on beauty, too oblique and maddeningly dreamlike to be an engaging story, and too devoid of interesting characters to hold your attention as they drift from one scene to the next. I’d be more forgiving of Refn’s indulgences if he was a short filmmaker. I’d allow more latitude for experimentation. The Neon Demon is not a movie. It’s a collection of half-formed, shallow ideas that Refn has thrown together, a whole lot of dead and empty space connecting them together, and an 80s synth score to underline the high-contrast colors. At this point I’d rather go back to the dentist than sit through another Refn film.

Nate’s Grade: D

Inherent Vice (2014)

This is one of the most difficult reviews I’ve ever had to write. It’s not because I’m torn over the film; no, it’s because this review will also serve as my break-up letter. Paul Thomas Anderson (PTA), we’re just moving in two different directions. We met when we were both young and headstrong. I enjoyed your early works Paul, but then somewhere around There Will be Blood, things changed. You didn’t seem like the PTA I had known to love. You became someone else, and your films represented this change, becoming plotless and laborious centerpieces on self-destructive men. Others raved to the heavens over Blood but it left me cold. Maybe I’m missing something, I thought. Maybe the problem is me. Maybe it’s just a phase. Then in 2012 came The Master, a pretentious and ultimately futile exercise anchored by the wrong choice for a main character. When I saw the early advertisements for Inherent Vice I got my hopes up. It looked like a weird and silly throwback, a crime caper that didn’t take itself so seriously. At last, I thought, my PTA has returned to me. After watching Inherent Vice, I can no longer deny the reality I have been ducking. My PTA is gone and he’s not coming back. We’ll always have Boogie Nights, Paul. It will still be one of my favorite films no matter what.

This is one of the most difficult reviews I’ve ever had to write. It’s not because I’m torn over the film; no, it’s because this review will also serve as my break-up letter. Paul Thomas Anderson (PTA), we’re just moving in two different directions. We met when we were both young and headstrong. I enjoyed your early works Paul, but then somewhere around There Will be Blood, things changed. You didn’t seem like the PTA I had known to love. You became someone else, and your films represented this change, becoming plotless and laborious centerpieces on self-destructive men. Others raved to the heavens over Blood but it left me cold. Maybe I’m missing something, I thought. Maybe the problem is me. Maybe it’s just a phase. Then in 2012 came The Master, a pretentious and ultimately futile exercise anchored by the wrong choice for a main character. When I saw the early advertisements for Inherent Vice I got my hopes up. It looked like a weird and silly throwback, a crime caper that didn’t take itself so seriously. At last, I thought, my PTA has returned to me. After watching Inherent Vice, I can no longer deny the reality I have been ducking. My PTA is gone and he’s not coming back. We’ll always have Boogie Nights, Paul. It will still be one of my favorite films no matter what.

In the drug-fueled world of 1970 Los Angeles, stoner private eye Doc (Joaquin Phoenix) is visited by one of his ex-girlfriends, Shasta (Katherine Waterston). She’s in a bad place. The man she’s in love with, the wealthy real estate magnate Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts) is going to be conned. Mickey’s wife, and her boyfriend, is going to commit the guy to a mental hospital ward and take control of his empire. Then Shasta and Mickey go missing. Doc asks around, from his police detective contact named Bigfoot (Josh Brolin), to an ex (Reese Witherspoon) who happens to be in the L.A. justice department, to a junkie (Jena Malone) with a fancy set of fake teeth thanks to a coked-out dentist (Martin Short) who may be a front for an Asian heroin cartel. Or maybe not. As more and more strange characters come into orbit, Doc’s life is placed in danger, and all he really wants to find out is whether his dear Shasta is safe or not.

In the drug-fueled world of 1970 Los Angeles, stoner private eye Doc (Joaquin Phoenix) is visited by one of his ex-girlfriends, Shasta (Katherine Waterston). She’s in a bad place. The man she’s in love with, the wealthy real estate magnate Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts) is going to be conned. Mickey’s wife, and her boyfriend, is going to commit the guy to a mental hospital ward and take control of his empire. Then Shasta and Mickey go missing. Doc asks around, from his police detective contact named Bigfoot (Josh Brolin), to an ex (Reese Witherspoon) who happens to be in the L.A. justice department, to a junkie (Jena Malone) with a fancy set of fake teeth thanks to a coked-out dentist (Martin Short) who may be a front for an Asian heroin cartel. Or maybe not. As more and more strange characters come into orbit, Doc’s life is placed in danger, and all he really wants to find out is whether his dear Shasta is safe or not.

Inherent Vice is a shaggy dog detective tale that is too long, too convoluted, too slow, too mumbly, too confusing, and not nearly funny or engaging enough. If it weren’t for the enduring pain that was The Master, this would qualify as Anderson’s worst picture.

One of my main complaints of Anderson’s last two movies has been the paucity of a strong narrative, especially with the plodding Master. It almost felt like Anderson was, subconsciously or consciously, evening the scales from his plot-heavy early works. Being plotless is not a charge one can levy against Inherent Vice. There is a story here with plenty of subplots and intrigue. The problem is that it’s almost never coherent, as if the audience is lost in the same pot haze as its loopy protagonist. The mystery barely develops before the movie starts heaping subplot upon subplot, each introducing more and more characters, before the audience has a chance to process. It’s difficult to keep all the characters and their relationships straight, and then just when you think you have everything settled, the film provides even more work. The characters just feel like they’re playing out in different movies (some I would prefer to be watching), with the occasional crossover. I literally gave up 45 minutes into the movie and accepted the fact that I’m not going to be able to follow it, so I might as well just watch and cope. This defeatist attitude did not enhance my viewing pleasure. The narrative is too cluttered with side characters and superfluous digressions.

The plot is overstuffed with characters, many of which will only appear for one sequence or even one scene, thus polluting a narrative already crammed to the seams with characters to keep track of. Did all of these characters need to be here and visited in such frequency? Doc makes for a fairly frustrating protagonist. He’s got little personality to him and few opportunities to flesh him out. Not having read Thomas Pynchon’s novel, I cannot say how complex the original character was that Anderson had to work with. Doc just seems like a placeholder for a character, a guy who bumbles about with a microphone, asking others questions and slowly unraveling a convoluted conspiracy. He’s more a figure to open other characters up than a character himself. The obvious comparison to the film and the protagonist is The Big Lebowski, a Coen brothers film I’m not even that fond over. However, with Lebowski, the Coens gave us memorable characters that separated themselves from the pack. The main character had a definite personality even if he was drunk or stoned for most of the film. Except for Short’s wonderfully debased and wily five minutes onscreen, every character just kind of washes in and out of your memory, only registering because of a famous face portraying him or her. Even in the closing minutes, the film is still introducing vital characters. The unnecessary narration by musician Joanna Newsome is also dripping with pretense.

Another key factor that limits coherency is the fact that every damn character mumbles almost entirely through the entirety of the movie. And that entirety, by the way, is almost two and a half hours, a running time too long by at least 30 minutes, especially when Doc’s central mystery of what happened to Shasta is over before the two-hour mark. For whatever reason, it seems that Anderson has given an edict that no actor on set can talk above a certain decibel level or enunciate that clearly. This is a film that almost requires a subtitle feature. There are so many hushed or mumbled conversations, making it even harder to keep up with the convoluted narrative. Anderson’s camerawork can complicate the matter as well. Throughout the film, he’ll position his characters speaking and slowly, always so slowly, zoom in on them, as if we’re eavesdropping. David Fincher did something similar with his sound design on Social Network, amping up the ambient noise to force the audience to tune their ears and pay closer attention. However, he had Aaron Sorkin’s words to work with, which were quite worth our attention. With Inherent Vice, the characters talk in circles, tangents, and limp jokes. After a protracted setup, and listening to one superficially kooky character after another, you come to terms with the fact that while difficult to follow and hear, you’re probably not missing much.