Blog Archives

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released September 17, 2004:

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow started as a six-minute home movie by Kerry Conran. He used computer software and blue screens to recreate New York City and depict a zeppelin docking at the top of the Empire State building. The six-minute short, which Conran spent several years completing, caught the attention of producer John Avnet (Fried Green Tomatoes). He commissioned Conran to flesh out a feature film, where computers would fill in everything except the actors (he even used the original short in the feature film). The dazzling, imaginative results are Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

Polly (Gwyneth Paltrow) is a reporter in 1930s New York. She?s investigating the mysterious disappearance of World War scientists when the city is invaded by a fleet of robots. The city calls out for the aid of Sky Captain, a.k.a. Joe (Jude Law), a dashing flying ace that happens to also be Polly?s ex. Joe and Polly form an uneasy alliance. He wants to stop Totenkopf (archived footage of Laurence Olivier) from sending robots around the globe and rescue his kidnapped mechanic, Dex (Giovanni Ribisi). She wants to get the story of a lifetime, a madman spanning the world to abduct scientists, parts, and the required elements to start a doomsday device. Along the way, Captain Franky Cook (Angelina Jolie) lends her help with her flying amphibious brigade. Together they might stop Totenkopf on his island of mystery.

Sky Captain is a visual marvel. It isn’t necessary a landmark, as actors have performed long hours behind green screen before (just look at the Star Wars prequels). Sky Captain is the first film where everything, excluding props the actors handle, is digitally brought to life inside those wonderful computers. The results are breath-taking, like when Polly enters Radio City Music Hall or during an underwater dogfight with Franky’s amphibious squadron. Sky Captain is brimming with visual excitement. The film is such an idiosyncratic vision that there’s no way it could have been made within the studio system.

Sky Captain has definite problems. For one, the characters are little more than stock characters going through the motions. The story also takes a backseat to the visuals. The dialogue is wooden and full of clunkers like, “You won’t need high heels where we’re going.” Generally the dialogue consists of one actor yelling the name of another character (examples include: “Dex!” “Joe!” “Polly!” and “Totenkopf!”). My father remarked that watching Sky Captain was akin to watching What Dreams May Come, because you’re captivated by the painterly visuals enough to stop paying attention to the less-than-there story and characters. The characters running onscreen also appears awkward, like they’re running on treadmills we can’t see, reminiscent of early 1990s video games.

Let’s talk then about those characters then. Paltrow’s character is generally unlikable. She’ll scheme her way toward whatever gains she wishes, but not in a chirpy Lois Lane style, more like a tabloid reporter. She whines, she yells, she complains, she berates, and she doesn’t so much banter as she does argue. Sky Captain is more enigmatic as a character. He seems forever vexed. Jolie’s Captain Franky Cook gives her another opportunity for her to use her faux-British accent. Jolie’s character is the strong-willed, sexy, helpful heroine that should be the center of the film, not Paltrow’s pesky reporter.

It’s also a bit undignified to assemble Laurence Olivier as the villain. It’s very unnecessary, but at least he wasn’t dancing with a vacuum cleaner.

Now, having acknowledged the flaws of Sky Captain, I must now say this: I do not care at all. This is the first time I’ve totally sidestepped a film’s flaws because of overall enjoyment. I have never felt as giddy as I did while watching Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. When the giant robots first showed up I was hopping in my seat. When I saw the mixture of 1930s sci-fi, adventure serials, and Max Fleischer cartoons, I was transported to being a little kid again. No movie has done this so effectively for me since perhaps the first Back to the Future. I loved that we saw map lines when we traveled from country to country. I love the fact that the radio signal hailing Sky Captain is reminiscent of the RKO Pictures opening.This is a whirling, lovelorn homage that will make generations of classic movie geeks will smile from ear to ear. I don’t pretend to brush over the flaws, with which story and characters might be number one, but Sky Captain left me on such a cotton-candy high that my eyes were glazing over.

One could actually make a legitimate argument that the stock characters, stiff dialogue, and anemic story are in themselves a clever homage to the sci-fi serials of old, where the good guys were brave, the women plucky, and the bad guys always bent on world domination. I won?t make this argument, but it could lend credence more toward the general flaws of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

Sky Captain is an exciting ode to influences of old. It’s periodically breath-taking in its visuals and periodically head scratching with its story, but the film might awaken childhood glee within the viewer. I won’t pretend the film isn’t flawed, and I know the primary audience that will love Sky Captain are Boomers with a love and appreciation for classic cinema. Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow will be a blast for a select audience, but outside of that group the film’s flaws may be too overwhelming.

Nate’s Grade: B+

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

When I first watched Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow in 2004, I was dazzled by its gee-whiz retro-futuristic homages and cutting-edge special effects. I wrote it felt like an appeal to your “Dad’s cinephile dad,” tapping into adventure serials and quaint sci-fi of Old Hollywood like Metropolis and Flash Gordon and German Expressionism and Max Fleischer cartoons. It was a giant nostalgic bombardment to a cinephile’s pleasure center. Now twenty years later, re-watching Sky Captain leaves me with a very different feeling. I found the majority of the movie in 2024 to be rather boring, and the special effects, while immersive and something special twenty years prior, are now dated and flawed. The whole thing propping up this underwritten homage enterprise are these murky visuals, making the ensuing 100 minutes feel much longer and more strained. It was transporting for me back in 2004, but now it just feels like empty homage run amok and lifted by special effects marked with an asterisk of history.

Sky Captain reminds me of 2001’s Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, a momentary breakthrough at the time of its release in special effects technology that was inevitably to be passed, thus serving as little more than a footnote in visual effects history. It’s now less compelling to revisit. At the time, entire movies weren’t constructed on giant green screen stages and completely in the powerhouse computers processing new worlds of imagination. Now, it feels like most studio blockbusters above a certain budget are completely shot on large, empty green screen warehouses. Now we have entire movies constructed in a three-dimensional play space inside a computer, like 2016’s The Jungle Book and 2019’s The Lion King. It wasn’t even that much longer before another artist would replicate writer/director Kerry Conran’s everything-green-screen-for-maximum-style approach. Just a few months later, in April 2005, Robert Rodriguez released the highly stylized Sin City movie, bringing to vivid life the striking monochromatic artwork of Frank Miller’s celebration of film noir, pulp comics, and busty dames. In that case, the visuals nearly pop off the screen, fashioning something that cannot be served through live-action alone. Re-watching Sky Captain, I found a lot of the visual effects to be dark and blurry, like the filmmakers added a grimy filter. Maybe it was an ode to making the effects less polished to better replicate its older influences, or maybe it was simply a matter of hiding its budget, but the effect is still the same, making the onscreen visuals that much harder to fully observe and appreciate. If the appeal is going to be the then-cutting-edge special effects, then don’t make choices that will mitigate that appeal.

The story is so episodic and flimsy, held together only by the references it bestows. I understand that Conran was trying to recreate the screwball banter of Old Hollywood, but I found the relationship between Sky Captain (Jude Law) and his ex Polly Perkins (Gwyneth Paltrow) to be excruciating. The bickering is heightened, as the overall tone of the movie is generally heightened, but that makes all human interaction feel wrongly calibrated. Polly comes across as obnoxious, worthy of being booted at many points throughout the globe-trotting adventure. She gets into trouble repeatedly while whining about her big journalistic scoop, or rehashing who was at fault for the detonation of their relationship. I think Law has better chemistry with Angelina Jolie, who appears late as a flying navy commander, and even Giovanni Ribisi as Sky Captain’s trusty ace mechanic. These people feel like they understood the assignment, playing into the heightened pulpy nature. Paltrow is hitting the wrong notes from the start, so her character comes across as annoying and in constant need of rescue. There’s a reason that Conran keeps the plot busy and skipping from one set piece to another, because the more time spent with our two main characters the more you realize they would be better served as transitory archetypes in a short film.

In many ways, it feels like Conran was worried that he might never direct another movie again, and so Sky Captain includes just about every nod possible to his influences. It can become its own Easter egg guessing game, making all the connections to stories film properties of old, like King Kong, War of the Worlds, The Wizard of Oz, to lesser known titles like Captain Midnight and King of the Rocket Men. There’s hidden worlds with dinosaurs, spaceship arks for a fresh start, and Laurence Olivier reappearing as manipulated archival footage as our mysterious deceased mad doctor. It’s somewhat fun to watch Conran be so transparent about his passions and influences. However, all these reverent homages and special effects closed loops are attached to a thin story with grating characters. Again, for a very select audience, dissecting all the reference points will be its own entertainment. For most viewers, Sky Captain will be a tin-eared bore that keeps throwing more reference points into its ongoing stew. Any ten minutes chosen at random will have the same value and impact as any other ten minutes throughout the movie.

Perhaps Conran was prescient because he has no other feature film credits in the ensuing twenty years. There was a point where he was attached for the big screen John Carter of Mars adaptation (as was Robert Rodriguez at one point) but he eventually left for unknown creative reasons. Considering how much buzz Sky Captain had as a project from an unknown outside the system, you might think it would serve as a proof of concept to at least get Conran to helm some other mid-level studio project.

The lasting legacy of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow will be its look, now replicated by many studio blockbusters, though Conran and his team did so without the same studio coffers. The thing I’ll remember most about Sky Captain isn’t my own enjoyment but my father;s a man who grew up reading pulp sci-fi magazines, watching saucer men movies, and instilling in me a love of older movies. I remember the delight this movie seemed to unleash inside him, returning him to a euphoric sense of his childhood. That’s the association I’ll have with this movie, even if my own entertainment level and appreciation has noticeably dipped in twenty years. I know there are other fans out there who may feel that same childlike wonder and glee from the movie. I hope you do, dear reader. For me, for now, it’s like seeing behind the magic trick and wishing you could still feel the same current of exhilaration. Alas.

Nate’s Grade: C

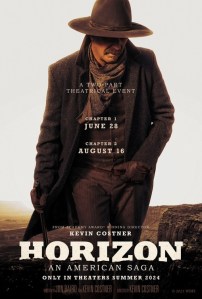

Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1 (2024)

I admire Kevin Costner throwing out all the stops to achieve his passion, a four-part, twelve-hour film series to showcase a sprawling Western epic. The man put a hundred million of his own money into the first two parts of Horizon: An American Saga, and the time devoted to this project was so all-consuming that Costner quit the Yellowstone series, a cable TV juggernaut getting bigger ratings every season. It’s ballsy all right, to abandon a monumentally successful series at the height of its zeitgeist popularity so he can direct not just one but four throwback Westerns that will ultimately be as long as the Lord of the Rings trilogy. It’s rare to see this level of sheer chutzpah in Hollywood. Horizon’s first part was released in June, with its completed second part intended to be released a mere two months later in August. After the poor box-office of Part One, the studio decided to pull Part Two from the release schedule, ostensibly to give people more time to catch the first movie. Will we ever see Part Two in theaters? Will we ever see Part Three, which Costner is currently filming, or Part Four, which Costner is currently raising money for? Costner intended to release the whole saga as a miniseries upon completion, and this might be the best case scenario. As a movie, albeit one quarter of an intended whole, Horizon Part One feels far more structured as an incomplete and rather prosaic TV series.

Upon the completion of the 170 minutes, I was left wondering what was here that would make someone want to come back for a lengthy second part, let alone a third and a fourth. It doesn’t feel like a complete movie or even a completed chapter, and again let me cite Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings series. Released over the course of three years, each movie had its own form of a beginning, middle, and end, with each climaxing around some event that left one satisfied by its conclusion. They didn’t just feel like chapters linking to the next; they felt like completed stories that pushed forward a larger overall story. Now, with Horizon Part One, it doesn’t feel like a three-hour movie, rather like three one-hour episodes of a TV series. Each of those hours feels too separate from the other. I’m reminded of television in the streaming era, where producers anticipate viewers binging through multiple episodes in speedy succession. This tacit assumption lends itself toward the general pacing issues I find with too many streaming series, where the filmmakers take far too long to get things moving in a significant manner. I’m reminded of a joke by Topher Florence that back in the day a show like Surf Dracula would feature its lead character surfing in weekly adventures, but the streaming age version would take its entire first season showing how he got his surfboard and then spend five minutes surfing in the finale. When you’re pacing out only one quarter of your possible intended story, calling it slow and lacking development and payoffs is an obvious hazard, which is why every movie needs to be its own thing, to provide a sense of conclusion even if it’s not the final conclusion.

Part One is divided into three parts: 1) the early settlers of Horizon, in the San Pedro Valley, being massacred by the Apache, 2) an old gunslinger (Kevin Costner) tasked with protecting a woman and child on the run from vengeful gunmen, 3) a wagon train of settlers headed to Horizon. Now, from that very streamlined synopsis, which of those storylines sounds the most exciting? Which of those storylines sounds like it can lend itself toward having an in-movie climax? Which of these storylines feels the most fraught with danger and intrigue? It’s the one starring Costner himself, of course, fitting naturally into the role of a tough curmudgeon.

I’m confused why the entire first hour of this movie is devoted to following the frontier town when we’re only going to get two survivors total that go forward. As far as its narrative importance, this entire section could have been condensed to a terrifying flashback from Frances Kittredge (Sienna Miller) and her daughter after the fact. The majority of this hour is spent watching the fine Christian folk of the early days of Horizon die horribly. We’re confined inside the battered Kittredge home that serves as the foundation of a siege thriller, with the band of various townspeople trapped and trying to fight off their indigenous intruders. The attack is prolonged and unsparing in its violence, eliminating all these nice, smiling faces from before. What does it add up to? It’s the tragic back-story for Frances, but it also makes her conveniently romantically unattached so that the nice cavalryman, Trent Gephart (Sam Worthington), can swoon and she can Learn to Love Again. It also sets up a young Apache warrior, Pionsenay (Owen Crow Shoe), making aggressive moves that his elders disagree with in their continued efforts to find some balance with the American settlers grabbing their territory. It also sets up what serves as the only possible character arc completion, with young Russell (Etienne Kellici) escaping the massacre in the beginning to then witness a massacre of Apache, and as he observes the scalping butchery, it galls him, not providing the relief of vengeance he had sought. Now that’s a conceivably emotional storyline, but Russell isn’t the primary character, or even one of the most essential supporting characters. You might genuinely forget about him like I did.

Something else I forgot an hour in was that Part One opens with Ellen Harvey (Jena Malone) shooting her abusive husband and running out. This prologue eventually comes back to setting up the present-day conflicts of the second hour, where Ellen has started a new life as Lucy with her young son. She lives in the Wyoming territory with a prostitute, Marigold (Abbey Lee). This storyline picks up significantly with new characters coming into the mix and disrupting the status quo. The first is Hayes Ellison (Costner) who finds himself attracted to Marigold, perhaps recognizing a woman in over her head. The second are the Sykes brothers (Jamie Campebell Bower, Jon Beavers) who have come looking to retrieve Lucy and her child, the son of their dearly departed pa who was slain in the opening. I am astounded that Costner decided to make the audience wait an hour for this segment because it feels like a much better fit to open Part One. There’s an immediacy to the looming danger and the consequences of actions, and what would serve as the Act One break is when Hayes has to intervene at great risk. This is, by far, the best segment of Horizon Part One. The ensuing on-the-run segment doesn’t get much further, setting up ongoing antagonism between the two sides that presumably will come to blows again. It’s not exactly reinventing the wagon wheel here: drifter reluctantly becoming protector for the vulnerable and reckoning with his shady past and trying to make amends. However, for this first movie, at least this storyline provides a sustained level of engagement with needed urgency.

The weakest portion is the wagon train led by Matthew Van Weyden (Luke Wilson). The most significant conflict during this section isn’t even the protection of the wagon train, it’s whether or not the hoity-toity British couple (Tom Payne, Anna and the Apocalypse‘s Ella Hunt) will assimilate to life on the prairie. They’re privileged, though at least he seems to recognize this. She bathes in the drinking water supply in an extended sponge bath sequence that feels so oddly gratuitous and leery. Two scouts are caught eagerly peeping and this seems like the most significant conflict of this whole section. They’re headed for Horizon, the setting of tragedy and indigenous conflict we know, but the entire wagon train lacks any feeling of dread or even the opposite, a feeling of yearning for a new life. It’s just a literal pileup of underwritten characters in movement without giving us a reason to care.

Costner’s Western eschews the trappings of modern revisionism, deconstructing the heroism and Manifest Destiny mythology of popular Wild West media. This isn’t a deconstruction but a full blown romantic classical Western, embracing the tropes with stone-faced gusto. In some ways it feels like Costner’s version of a Taylor Sheridan show (1883, Yellowstone). He left a Sheridan show to make his own Sheridan show. It’s more measured in its portrayal of the Native Americans even as it shows them massacring men, women, and children as our first impression. I wager Costner is showing that the evils of violent tendencies pervade both sides of the conflict, with a troop of American scalp-hunters that don’t really care where those scalps come from. It’s hard to fully articulate the themes given this is only one-fourth of the overall intended picture. The expansive settings are stunning and gorgeously filmed. I can understand why Costner would want people to watch this movie on the big screen with scenery this beautiful from cinematographer J. Michael Muro, who served as Costner’s DP on 2003’s Open Range, another muscular Western. Fun fact: Muro also served as a Steadicam operator on Costner’s Best Picture-winning Dances with Wolves, so their professional relationship goes back thirty-five years and covers Costner’s love affair with Westerns.

During its conclusion, Horizon: An American Saga runs through a wordless montage of clips that serves as a trailer for the forthcoming Part Two. It’s not edited like a trailer, more so a very leisurely preview with clips that look good but, absent context, can be shrug-worthy. Oh look, a character looking out a window pensively. Oh look, a character walking along a trail. Oh look, a character dismounting from a horse. Oh look, another character looking out a window pensively. It’s hard for me to fathom this truncated preview getting too many people excited for what Part Two has to offer, but then I think that’s the same problem with Part One. It doesn’t serve as a grabber, with characters we really care about, with conflicts that keep us glued, and with revelations and character turns that can keep us intrigued and desperately wanting more. It’s hard for me to think of that many people walking out of Part One and being ravenous for nine more hours. I accept that stories might feel incomplete and characters might feel disjointed, but Horizon is perhaps a Western best left in the distance, at least until you can binge it in its completed form, whatever that may be, though I doubt we’re going to get four full movies. Ultimately, Costner’s opus will need to be judged as a whole rather than as consecutive parts.

Nate’s Grade: C

Cold Mountain (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released December 25, 2003:

Premise: At the end of the Civil War, Inman (Jude Law, scruffy) deserts the Confederate lines to journey back home to Ada (Nicole Kidman), the love of his life he’s spent a combined 10 minutes with.

Results: Terribly uneven, Cold Mountain‘s drama is shackled by a love story that doesn’t register the faintest of heartbeats. Kidman is wildly miscast, as she was in The Human Stain, and her beauty betrays her character. She also can’t really do a Southern accent to save her life (I’m starting to believe the only accent she can do is faux British). Law’s ever-changing beard is even more interesting than her prissy character. Renee Zellweger, as a no-nonsense Ma Clampett get-your-hands-dirty type, is a breath of fresh air in an overly stuffy film; however, her acting is quite transparent in an, “Aw sucks, give me one ‘dem Oscars, ya’ll” way.

Nate’’s Grade: C

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I kept meaning to come back to Cold Mountain, a prototypical awards bait kind of movie that never really materialized, but one woman ensured that it would be on my re-watch list for 2003. My wife’s good friend, Abby, was eager to hear my initial thoughts on the movie when I wrote my original review at the age of twenty-one. This is because Cold Mountain is a movie that has stayed with her for the very fact that her grandfather took her to see it when she was only nine years old. While watching, it dawned on nine-year-old Abby that this was not a movie for nine-year-olds, and it’s stuck with her ever since. I think many of us can relate to watching a movie with our parents or family members that unexpectedly made us uncomfortable. For me, it was Species, where I was 13 years old and the movie was about a lady alien trying to procreate. I think my father was happy that I had reached an acceptable age to go see more R-rated movies in theaters. Social media has been awash lately with videos of festive families reacting to the shock value of Saltburn with grumbles and comical discomfort (my advice: don’t watch that movie with your parents). So, Abby, this review is for you, but it’s also, in spirit, for all the Abbys out there accidentally exposed to the adult world uncomfortably in the company of one’s parents or extended family.

Cold Mountain succumbs to the adaptation process of trying to squeeze author Charles Frazier’s 1997 book of the same name into a functional movie structure, but the results, even at 150 minutes, are unwieldy and episodic, arguing for the sake of a wider canvas to do better justice to all the themes and people and minor stories that Frazier had in mind. Director Anthony Minghella’s adaptation hops from protagonist to protagonist, from Inman to Ada, like perspectives for chapters, but there are entirely too many chapters to make this movie feel more like a highly diluted miniseries scrambling to fit all its intended story beats and people into an awards-acceptable running time. This is a star-studded movie, the appeal likely being working with an Oscar-winning filmmaker (1996’s The English Patient) of sweep and scope and with such highly regarded source material, a National Book Award winner. The entire description of Cold Mountain, on paper, sounds like a surefire Oscar smash for Harvey Weisntein to crow over. Yet it was nominated for seven Academy Awards but not Best Picture, and it only eventually won a single Oscar, deservedly for Renee Zellweger. I think the rather muted response to this Oscar bait movie, and its blip in a lasting cultural legacy, is chiefly at how almost comically episodic the entire enterprise feels. This isn’t a bad movie by any means, and quite often a stirring one, but it’s also proof that Cold Mountain could have made a really great miniseries.

The leading story follows a disillusioned Confederate defector, Inman (Jude Law), desperately trying to get back home to reunite with his sworn sweetheart, Ada (Nicole Kidman), who is struggling mightily to maintain her family’s farm after the death of her father. That’s our framework, establishing Inman as a Civil War version of Odysseus fighting against the fates to return home. Along the way he surely encounters a lot of famous faces and they include, deep breath here, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Natalie Portman, Giovanni Ribisi, Cillian Murphy, Eileen Atkins, Taryn Manning, Melora Walters, Lucas Black, and Jena Malone. Then on Ada’s side of things we have Zellweger, Donald Sutherland, a villainous Ray Winstone, Brendan Gleeson, Charlie Hunam, Kathy Baker, Ethan Suplee, musician Jack White, and Emily Descehanel, and this is the storyline that stays put in the community of Cold Mountain, North Carolina.

That is a mountain of stars, and with only 150 minutes, the uneven results can feel like one of those big shambling movies from the 1950s that have dozens of famous actors step on and as quickly step off the ride. Poor Jena Malone (Rebel Moon) appears as a ferry lady and literally within seconds of offering to prostitute herself she is shot dead and falls into the river (well, thanks for stopping by Jena Malone, please enjoy your parting gift of this handsome check from Miramax). Reducing these actors and the characters they are playing down to their essence means we get, at most, maybe 10-15 minutes with them and storylines that could have been explored in richer detail. Take Portman’s character, a widowed mother with a baby trying to eke out a living, one of many such fates when life had to continue after the men ran to war for misbegotten glory. She looks at Inman with desperate hunger, but it’s not exactly lust, it’s more human connection. When she requests that Inman share her bed, it’s just to feel another warm presence beside her, someone that can hold her while she weeps about the doomed fate of her husband and likely herself. There’s a strong character here but she’s only one stop on our expedited tour. The same with Hoffman’s hedonistic priest, a man introduced by throwing the body of a slave woman he impregnated over a ridge, which might be the darkest incidental moment of the whole movie. His character is played as comic relief, a loquacious man of God who cannot resist the pleasures of the flesh, but even he comes and goes like the rest of our litany of very special guest stars. They feel more like ideas than characters.

This is a shame because there are some fantastic scenes and moments that elevate Cold Mountain. The opening Civil War battle is an interesting and largely forgotten (sorry Civil War buffs) battle that begins with a massive surprise attack that produces a colossal explosion and crater and turns into a hellish nightmare. Granted, the movie wants us to sympathize with the Confederates who were bamboozled by the Yankee explosives buried under their lines, and no thank you. The demise of Hoffman’s character comes when he and Inman are captured and join a chain gang, and they try running up a hill to get free from approaching Union troops. The Confederates shoot at the fleeing men, eventually only with Inman left, who struggles to move forward with the weight of all these dead men attached to him. When they start rolling down the hill, it becomes a deeply macabre and symbolic struggle. The stretch with Portman (May December) is tender until it goes into histrionics, with her literal baby being threatened out in the cold by a trio of desperate and starving Union soldiers (one of which played by Cillian Murphy). It’s a harrowing scene that reminds us about the sad degradation of war that entangles many innocents and always spills over from its desired targets. However, this theme that the war and what it wrought is sheer misery is one Minghella goes to again and again, but without better characterization with more time for nuance, it feels like each character and moment is meant to serve as another supporting detail in an already well-proven thesis of “war is hell.”

Even though I had previously watched the movie back in 2003, I was hoping that after two hours of striving to reunite, that Inman and Ada would finally get together and realize, “Oh, we don’t actually like each other that much,” that their romance was more a quick infatuation before the war, that both had overly romanticized this beginning and projected much more onto it from the years apart, and now that they were back together with the actual person, not their idealized imaginative version, they realized what little they had in common or knew about each other. It would have been a well-played subversion, but it also would have been a welcomed shakeup to the Oscar-bait romantic drama of history. Surely this had to be an inconvenient reality for many, especially considering that the men returning from war, the few that did, were often not the same foolhardy young men who leapt for battle.

Zellweger (Judy) was nominated for Best Actress in the preceding two years, for 2001’s Bridget Jones Diary and 2002’s Chicago, which likely greased the runway for her Supporting Actress win from Cold Mountain. There is little subtlety about her “aw shucks” homespun performance but by the time she shows up, almost fifty minutes into the movie, she is such a brash and sassy relief that I doubt anyone would care. She’s the savior of the Cold Mountain farm, and she’s also the savior of the flagging Ada storyline. Pity Ada who was raised to be a nice dutiful wife and eventual mother but never taught practical life skills and agricultural methods. Still, watching this woman fail at farming will only hold your attention for so long. Zellweger is a hoot and the spitfire of the movie, and she even has a nicely rewarding reconciliation with her besotted old man, played by Brendan Gleeson, doing his own fiddlin’ as an accomplished violin player. As good as Zellweger is in this movie is exactly how equally bad Kidman’s performance is. Her Southern accent is woeful and she cannot help but feel adrift, but maybe that’s just her channeling Ada’s beleaguered plight.

I think there’s an extra layer of entertainment if you view Inman’s journey in league with Odysseus; there’s the dinner that ends up being a trap, the line of suitors trying to steal Ada’s home and hand in the form of the duplicitous Home League boys, Hoffman’s character feels like a lotus eater of the first order, and I suppose one reading could have Portman’s character as the lovesick Calypso. Also, apparently Cold Mountain was turned into an opera in 2015 from the Sante Fe Opera company. You can listen here but I’m not going to pretend I know the difference between good and bad opera. It’s all just forceful shouting to my clumsy ears.

Miramax spent $80 million on Cold Mountain, its most expensive movie until the very next year with 2004’s The Aviator. Miramax was sold in 2010 and had years earlier ceased to be the little studio that roared so mighty during many awards seasons. I think Cold Mountain wasn’t the nail in the coffin for the company but a sign of things to come, the chase for more Oscars and increasingly surging budgets lead the independent film distributor astray from its original mission of being an alternative to the major studio system. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, it had simply become another studio operating from the same playbook. Minghella spent three years bringing Cold Mountain to the big screen, including a full year editing, and only directed one other movie afterwards, 2006’s Breaking and Entering, a middling drama that was his third straight collaboration with Law. Minghella died in 2008 at the still too young age of 54. He never lived to fully appreciate the real legacy of Cold Mountain: making Abby and her grandfather uncomfortable in a theater. If it’s any consolation to you, Abby, I almost engineered my own moment trying to re-watch this movie and having to pause more than once during the sex scene because my two children wanted to keep intruding into the room. At least I had the luxury of a pause button.

Re-View Grade: B-

Lost in Translation (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released October 3, 2023:

Originally released October 3, 2023:

Sofia Coppola probably has had one of the most infamous beginnings in showbiz. Her father, Francis Ford, is one of the most famous directors of our times. He was getting ready to film Godfather Part III when Winona Ryder dropped out weeks before filming. Sophia Coppola, just at the age of 18, stepped into the role of Michael Corleone’s daughter. The level of scathing reviews Coppolas acting received is something perhaps only Tom Green and Britney Spears can relate to. Coppola never really acted again. Instead she married Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich) and adapted and directed the acclaimed indie flick, The Virgin Suicides. So now Coppola is back again with Lost in Translation, and if this is the kind of rewards reaped by bad reviews early in your career, then I’m circling the 2008 Oscar date for Britney.

Bob Harris (Bill Murray) is a washed up actor visiting Tokyo to film some well-paying whiskey commercials. Bob’s long marriage is fading and he feels the pains of loneliness dig its claws into his soul. Bob finds a kindred spirit in Charlotte (Scarlet Johansson), a young newlywed who has followed her photographer husband (Giovanni Ribisi) to Japan and is second-guessing herself and her marriage. The two strike up a friendship of resistance as strangers in a strange land. They run around the big city and share enough adventures to leave an indelible impression on each other’s life.

Lost in Translation is, simply put, a marvelously beautiful film. The emphasis for Coppola is less on a rigidly structured story and more on a consistently lovely mood of melancholy. There are many scenes of potent visual power, nuance of absence, that the viewer is left aching like the moments after a long, cleansing cry. There are certain images (like Johansson or Murray staring out at the impersonal glittering Tokyo) and certain scenes (like the final, tearful hug between the leads) that I will never forget. Its one thing when a film opens on the quiet image of a woman’s derriere in pink panties and just holds onto it. It’s quite another thing to do it and not draw laughs from an audience.

Lost in Translation is, simply put, a marvelously beautiful film. The emphasis for Coppola is less on a rigidly structured story and more on a consistently lovely mood of melancholy. There are many scenes of potent visual power, nuance of absence, that the viewer is left aching like the moments after a long, cleansing cry. There are certain images (like Johansson or Murray staring out at the impersonal glittering Tokyo) and certain scenes (like the final, tearful hug between the leads) that I will never forget. Its one thing when a film opens on the quiet image of a woman’s derriere in pink panties and just holds onto it. It’s quite another thing to do it and not draw laughs from an audience.

Murray is outstanding and heartbreaking. Had he not finally gotten the recognition he deserved with last year’s Oscar nomination I would have raged for a recounting of hanging chads. Murray has long been one of our most gifted funnymen, but later in his career he has been turning in soulful and stirring performances playing lonely men. When Murray sings Roxy Music’s “More Than This” to Johansson during a wild night out at a karaoke bar, the words penetrate you and symbolize the leads’ evolving relationship.

Johansson (Ghost World) herself is proving to be an acting revelation. It is the understatement of her words, the presence of a mature intelligence, and the totality of her wistful staring that nail the emotion of Charlotte. Never does the character falter into a Lolita-esque vibe. Shes a lonely soul and finds a beautiful match in Murray.

Lost in Translation is an epic exploration of connection, and the quintessential film that perfectly frames those inescapable moments of life where we come into contact with people who shape our lives by their short stays. This is a reserved love story where the most tender of actions are moments like Murray carrying a sleeping Johansson to her room, tucking her in, then locking the door behind. The comedy of disconnect is delightful, like when Murray receives incomprehensible direction at a photo shoot. The score by Jean-Benoît Dunckel, front man of the French duo Air, is ambient and wraps around you like a warm blanket. The cinematography is also an amazing experience to behold, especially the many shots of the vast glittering life of Tokyo and, equally, its emptiness.

Lost in Translation is an epic exploration of connection, and the quintessential film that perfectly frames those inescapable moments of life where we come into contact with people who shape our lives by their short stays. This is a reserved love story where the most tender of actions are moments like Murray carrying a sleeping Johansson to her room, tucking her in, then locking the door behind. The comedy of disconnect is delightful, like when Murray receives incomprehensible direction at a photo shoot. The score by Jean-Benoît Dunckel, front man of the French duo Air, is ambient and wraps around you like a warm blanket. The cinematography is also an amazing experience to behold, especially the many shots of the vast glittering life of Tokyo and, equally, its emptiness.

Everything works so well in Lost in Translation, from the bravura acting, to the stirring story, to the confident direction, that the viewer will be caught up in its lovely swirl. The film ends up becoming a humanistic love letter to what brings us together and what shapes how we are as people. Coppola’s film is bursting with such sharply insightful, quietly touching moments, that the viewer is overwhelmed at seeing such a remarkably mature and honest movie. The enjoyment of Lost in Translation lies in the understanding the audience can feel with the characters and their plight for connection and human warmth.

Writer/director Sofia Coppola’s come a long way from being Winona Ryder’s last-second replacement, and if Lost in Translation, arguably the best film of 2003, is any indication, hopefully well see even more brilliance yet to come. This is not going to be a film for everyone. A common argument from detractors is that Lost in Translation is a film lost without a plot. I’ve had just as many friends call this movie “boring and pointless” as I’ve had friends call it “brilliant and touching.” The right audience to enjoy Lost in Translation would be people who have some patience and are willing to immerse themselves in the nuances of character and silence.

Nate’s Grade: A

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I have never done this before in the four years of my re-reviewing movies, but I really just want to quote my introduction into Lost in Translation because I feel like this perfectly sets the scene, as well as giving my 21-year-old self some kudos: “Sofia Coppola probably has had one of the most infamous beginnings in showbiz. Her father, Francis Ford, is one of the most famous directors of our times. He was getting ready to film Godfather Part III when Winona Ryder dropped out weeks before filming. Sophia Coppola, just at the age of 18, stepped into the role of Michael Corleone’s daughter. The level of scathing reviews Coppola’s acting received is something perhaps only Tom Green and Britney Spears can relate to. Coppola never really acted again… So now Coppola is back again with Lost in Translation, and if this is the kind of rewards reaped by bad reviews early in your career, then I’m circling the 2008 Oscar date for Britney.” Besides the unnecessary broadside against Ms. Spears, who I’ve already apologized for with my re-review of 2002’s Crossroads, I think all this holds true. Within three films, Sofia Coppola went from an unfortunate punchline (not her fault!) to Oscar winner and indie darling.

Lost in Translation was my favorite American movie of 2003, so I’m always curious how my then-favorites stack up twenty years later. I’ve softened on American Beauty and Requiem for a Dream, and still consider The Iron Giant, Magnolia, and Moulin Rouge to be excellent. My feelings toward Lost in Translation, upon re-watch, remain mostly the same, though after two decades of watching other slow-burn, character-centric indies and widening my viewing, its highs aren’t quite the rhapsodic high for me in 2023 but it’s still an effective melancholy mood piece.

Lost in Translation taps directly into a universal feeling of yearning for connections in a time where it’s becoming easier and easier to disconnect into our own little bubbles. You don’t have to be stuck in a foreign country to feel isolated or out of sorts, and Coppola uses the external circumstances as a means of reinforcing the emotional isolation and then re-connection of her characters. This is why I brush aside some of the harsher criticisms levied against Coppola’s portrayal of Japanese culture and the locals. This is an outsider portrayal, and I don’t think there’s so much a critical judgment over Japanese culture as being inferior as just being different from what these characters are used to. They are clearly out of their element; it’s not that the culture is weird, it’s that the culture is different (that doesn’t mean there aren’t some overstayed stereotypes here as well). Trying to simply communicate with people that all speak another language is a quick and accessible dynamic to better visualize and articulate disconnect. I feel like this story could have been told from any racial or ethical perspective; it’s about two outsiders finding one another. The racial dynamics are less important. Obviously Coppola’s own personal experiences and outsider perspective in Japan are what provides the specific details with this tale, but I think what makes the movie still so effective in 2023 is because it’s so relatable on a deeper level that it eclipses any specific personal details. It’s about feeling lost and then feeling seen.

Lost in Translation taps directly into a universal feeling of yearning for connections in a time where it’s becoming easier and easier to disconnect into our own little bubbles. You don’t have to be stuck in a foreign country to feel isolated or out of sorts, and Coppola uses the external circumstances as a means of reinforcing the emotional isolation and then re-connection of her characters. This is why I brush aside some of the harsher criticisms levied against Coppola’s portrayal of Japanese culture and the locals. This is an outsider portrayal, and I don’t think there’s so much a critical judgment over Japanese culture as being inferior as just being different from what these characters are used to. They are clearly out of their element; it’s not that the culture is weird, it’s that the culture is different (that doesn’t mean there aren’t some overstayed stereotypes here as well). Trying to simply communicate with people that all speak another language is a quick and accessible dynamic to better visualize and articulate disconnect. I feel like this story could have been told from any racial or ethical perspective; it’s about two outsiders finding one another. The racial dynamics are less important. Obviously Coppola’s own personal experiences and outsider perspective in Japan are what provides the specific details with this tale, but I think what makes the movie still so effective in 2023 is because it’s so relatable on a deeper level that it eclipses any specific personal details. It’s about feeling lost and then feeling seen.

The key scene for me happens about seventy minutes into the movie, after Bob (Bill Murray) and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) have had an adventure with the Japanese hospital system. They’ve become one another’s insomnia buddies, teaming up to explore the city’s nightlife. As they lay side by side in bed during the wee hours, they have an intimate and poignant conversation, and it has nothing to do with sex. “I’m stuck,” she says. “Does it get any easier?” It’s about a young woman asking a middle-aged man for guidance and wisdom and him offering what he can with the caveat that he too is still struggling for his own wisdom. It’s the illusion that at some magic predetermined number of trips around the sun, the mystery of life will somehow become perfectly realized, as if now we can see the grand architectural design. There is no magic number. Everyone is trying their best and making it up as they go, and that’s what this conversation represents. She’s begging for reassurances that adult life will get easier, that she’ll find her footing, and Bob encourages her to continue pursuing her hobbies and passions even if she can’t stand her own art (which sounds like every artist I’ve ever known). Much of his actionable advice comes down to being patient including with yourself. Everybody is in their own way trying their best with what they have. He assures her that the more she gets comfortable with who she is the less things can bother her. It’s a beautiful scene and the reason it works even better is that Coppola doesn’t treat this moment with the gravity it has. It’s not even the film’s climax. Much like real life, when we look back at the exchanges that prove the most formative, we don’t have alarms ringing to better inform us that this is a moment that will have maximum import. We don’t know until it’s over.

I have never viewed Lost in Translation as some kind of will-they-won’t-they May-December romance, and at no point was I secretly hoping that Bob and Charlotte would get together. This is because they do get together but it’s not a purely romantic connection, although once you start really analyzing romance itself, there are far more complicated and nuanced dimensions to this overly simplified concept, and one could argue this is a romance of sorts but not one about physical passion and infatuation that dominate our association. It’s about two human souls drifting along in life who find a kinship with one another when they need it the most. I never wondered at the end whether they would kiss or have some kind of affair or even run off together, because that wasn’t what was so essential to this dynamic. It wasn’t how far they would go for love, including what would they give up or who would they hurt, it was about each of them serving as a life preserver, something to hold onto during a turbulent time. I truly believe that if they had kissed and had some kind of tawdry love affair that the film would have been cheapened. When Bob carries Charlotte back into her hotel room bed, I never viewed this act as two lovers but of a father and daughter. It’s too easy to just reduce every relationship into a sexual pairing. We all have meaningful relationships with many people who occupy different spheres of our life and our experiences, and our lives could be irreversibly altered without their influence no matter how fleeting our time together may have been. To reduce everything into whether they spark something sexual or passionate is just plain boring.

I have never viewed Lost in Translation as some kind of will-they-won’t-they May-December romance, and at no point was I secretly hoping that Bob and Charlotte would get together. This is because they do get together but it’s not a purely romantic connection, although once you start really analyzing romance itself, there are far more complicated and nuanced dimensions to this overly simplified concept, and one could argue this is a romance of sorts but not one about physical passion and infatuation that dominate our association. It’s about two human souls drifting along in life who find a kinship with one another when they need it the most. I never wondered at the end whether they would kiss or have some kind of affair or even run off together, because that wasn’t what was so essential to this dynamic. It wasn’t how far they would go for love, including what would they give up or who would they hurt, it was about each of them serving as a life preserver, something to hold onto during a turbulent time. I truly believe that if they had kissed and had some kind of tawdry love affair that the film would have been cheapened. When Bob carries Charlotte back into her hotel room bed, I never viewed this act as two lovers but of a father and daughter. It’s too easy to just reduce every relationship into a sexual pairing. We all have meaningful relationships with many people who occupy different spheres of our life and our experiences, and our lives could be irreversibly altered without their influence no matter how fleeting our time together may have been. To reduce everything into whether they spark something sexual or passionate is just plain boring.

This was a turning point in the careers of all three of its major figures. For Coppola, it was confirmation of her artistic voice and stepping from the long shadow of her father. She won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and was nominated for Best Director, only the third woman ever at that time. That’s a big deal. This was a statement film for her and she’s been making very leisurely paced, lushly photographed, somber character pieces since, very Sofia Coppola Movies (her latest promises to highlight the perspective of Priscilla Pressly). She never quite had another movie land as well as this one though 2006’s Marie Antoinette is due for a reappraisal as well. For Murray, it was confirmation that he had real dramatic acting skills that he’d shown flashes of in other movies like The Razor’s Edge and Rushmore, and it earned him his only Academy Award nomination. For Johansson, it was also the beginning of establishing her as an adult actress of serious caliber, and there was a critical stir that she had been snubbed by the Academy in 2004 not just for her role in Lost in Translation but also Girl with Pearl Earring. Johansson had been a steadily working actress since she was a child, and this was confirmation that she was ready to make the next jump. From there, she found a creative kinship with Woody Allen, and Wes Anderson, and even became an action movie star that could headline her own blockbusters. She finally got her first Oscar nominations in 2019, for both Marriage Story and Jojo Rabbit, becoming only the twelfth actor ever to be nominated twice in the same year. Murray’s star has fallen out of favor recently from his onerous onset behavior, though he did reunite with Coppola for 2020’s On the Rocks.

One of the stranger post-scripts for this movie relates to Johansson’s singing. The karaoke scene in Lost in Translation is one of the best, and it works on a magical elemental level where the music becomes our means of expression. When Murray sings “More Than This,” it’s hard not to read more into the moment. It’s right there in the song choice. Both actors do their own singing, adding to the fun and authenticity. Johansson would later release her own album in 2008 titled Anywhere I Lay My Head. It wasn’t uncommon for young actresses to moonlight as singers for a vanity project (Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan did this too), but what set this album apart was that it was almost entirely comprised of Tom Waits covers. According to Yahoo, as of August 2009, it had sold only 25,000 copies, which to be fair is twenty-five thousand more than I’ve ever sold, so what do I know? She released one more music album, 2009’s Break Up.

One of the stranger post-scripts for this movie relates to Johansson’s singing. The karaoke scene in Lost in Translation is one of the best, and it works on a magical elemental level where the music becomes our means of expression. When Murray sings “More Than This,” it’s hard not to read more into the moment. It’s right there in the song choice. Both actors do their own singing, adding to the fun and authenticity. Johansson would later release her own album in 2008 titled Anywhere I Lay My Head. It wasn’t uncommon for young actresses to moonlight as singers for a vanity project (Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan did this too), but what set this album apart was that it was almost entirely comprised of Tom Waits covers. According to Yahoo, as of August 2009, it had sold only 25,000 copies, which to be fair is twenty-five thousand more than I’ve ever sold, so what do I know? She released one more music album, 2009’s Break Up.

Looking back at my original 2003 review, it’s easy to see how smitten I was discovering Lost in Translation and trying to argue its virtues in my college newspaper. I think I assumed most of my fellow collegians would rather watch raunchy comedies like Van Wilder rather than a slow-burn indie about sad people roaming a foreign city. To this day I still have an equal number of friends who deem Lost in Translation as slow navel-gazing fluff to beautiful and beguiling. As I said before, it’s a mood piece about disconnected people, and I think if you’re in the right mood, or an open mind with the patience to spare, then there’s still something appealing and rewarding about an understated movie about two lonely people finding an unexpected kinship that defies reductive romantic classification. I just experienced something on this level with 2023’s Past Lives. I’m glad that Coppola has kept the final whisper between Bob and Charlotte a secret because it doesn’t matter what he specifically says so much as the meaning of this exchange for the both of them. It’s a goodbye of sorts but also a recognition of one another’s help and compassion. It’s not for us to hear. It’s too intimate. It’s a perfect ending for a film that still proves indelible twenty years later.

Re-View Grade: A-

The Bad Batch (2017)

Days after viewing writer/director Ana Lily Amirpour’s The Bad Batch, I’m still contemplating what I just saw. That can be the sign of a good, thought-provoking movie, or it could be further proof that The Bad Batch is really an empty experience.

Days after viewing writer/director Ana Lily Amirpour’s The Bad Batch, I’m still contemplating what I just saw. That can be the sign of a good, thought-provoking movie, or it could be further proof that The Bad Batch is really an empty experience.

In a not-too-distant future, the United States has found a unique solution to crime. Those deemed irredeemable are tattooed with “bad batch” and abandoned into the American Southwest. It’s a dusty land of outlaws that the U.S. doesn’t even recognize. Arlen (Suki Waterhouse) is deposited into the wastes of the Southwest and she is abducted by cannibals who make a meal out of her right arm and leg. She escapes and finds Comfort, a small outpost where she can heal and find community. The makeshift leader of Comfort is The Dream (Keanu Reeves), a messianic figure who doles out free drugs to the townspeople. He also has a harem of pregnant women. Miami Man (Jason Momoa), one of the hunkier cannibals, loses his daughter and forces Arlen to help him.

I’m going to summarize the sparse two-hour plot, dear reader, to share with you just how little there is to this film (will keep spoilers mild). Arlen gets kidnapped. She escapes. Months later she kills one of the cannibals. She quasi-adopts a little girl. Her father goes searching for her. Arlen loses the little girl. The father finds Arlen. They find the little girl who was unharmed. They eat a bunny. The end. Now admittedly any movie can sound rather flimsy when boiled down to its essential story elements (Star Wars: “Space farmer accepts call to adventure. Rescues princess.”) but the counterbalance is substance. Characters, world building, arcs, plot structure, setups and payoffs, all of it opens up the film’s story beats into a larger and transformative work. That’s simply not there with The Bad Batch. It’s a vapid film that has too much free time to fill, so you get several shots that are simply people riding motorcycles up to the camera. I grew restless waiting for something of merit to happen. Arlen simply just walks out into the desert like three different times, and this is after she was captured by roving cannibals that are still out there in healthy numbers. If you went to a store and the owner captured you and cut off your arm, would you venture back in that direction? Maybe there’s a commentary about victimhood and the cycle of abuse and exploitation, or maybe I’m left to intuit some kind of grander implication out of a filmmaker’s lack of effort. There’s just not enough here to justify its running time. It feels stretched beyond the breaking point.

I’m going to summarize the sparse two-hour plot, dear reader, to share with you just how little there is to this film (will keep spoilers mild). Arlen gets kidnapped. She escapes. Months later she kills one of the cannibals. She quasi-adopts a little girl. Her father goes searching for her. Arlen loses the little girl. The father finds Arlen. They find the little girl who was unharmed. They eat a bunny. The end. Now admittedly any movie can sound rather flimsy when boiled down to its essential story elements (Star Wars: “Space farmer accepts call to adventure. Rescues princess.”) but the counterbalance is substance. Characters, world building, arcs, plot structure, setups and payoffs, all of it opens up the film’s story beats into a larger and transformative work. That’s simply not there with The Bad Batch. It’s a vapid film that has too much free time to fill, so you get several shots that are simply people riding motorcycles up to the camera. I grew restless waiting for something of merit to happen. Arlen simply just walks out into the desert like three different times, and this is after she was captured by roving cannibals that are still out there in healthy numbers. If you went to a store and the owner captured you and cut off your arm, would you venture back in that direction? Maybe there’s a commentary about victimhood and the cycle of abuse and exploitation, or maybe I’m left to intuit some kind of grander implication out of a filmmaker’s lack of effort. There’s just not enough here to justify its running time. It feels stretched beyond the breaking point.

If the film is meant to be about immersion, something that holds together via hypnotic Lynchian dream logic, then it better work hard to hold my attention since plot has already been abandoned. This is where The Bad Batch also lost me. It’s just not weird enough, though even weird-for-weird’s-sake can be insufferable, like Harmony Korine’s Gummo. Amirpour (A Girl Walks Home at Night) has an innate feel for visual arrangements and little quirky touches that can burn into your memory, like the sight of Arlen sidling next to a magazine clipping of a model’s arm she taped to a mirror or a well-armed pregnant militia. The most interesting elements of the story are left unattended though. This is a vague dystopia where the government has decided to let the “bad batch” fend for themselves in a desert. It screams neo-Western with a lawless land populated with criminals and killers. There are only ever two locations we visit: the cannibal’s junkyard and the outpost of Comfort. Do we know anything about these locations? Are they at war? Is there some kind of understanding between them wherein Comfort offers sacrifices for protection? Is there an uneasy peace that could be spoiled thanks to Arlen’s vengeance? It’s all just vast wasteland, but even when they get to actual places, it still feels like empty space. How can you make something about dystopian cannibals be this singularly boring?

The characters just aren’t worth your attention and ultimately don’t matter in service of story or even a potential message. Arlen is much more of a figurehead than a person, and perhaps that’s why the director chose Waterhouse (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies) as her lead. The former model certainly makes a visually striking figure and knows how to arc her body in non-verbal ways to communicate feelings. However, I don’t know if there’s a good actress here. There’s no real reason to take away her arm and leg except that it looks cool and edgy. Initially it presents a visceral vulnerability for her and a disadvantage of escape, but after she arrives in Comfort, it’s as if she’s just any other able-bodied character. It feels like the director just liked the look and thought it would grab attention or say something meaningful. Momoa (Justice League) has a natural intimidating screen presence but he’s given so little to do. He’s just on glower autopilot. Miami Man is a killer and we watch him cook people’s limbs for some good eats. It’s almost like the movie wants you to forget this stuff when his paternal instincts kick in. Rather than embracing the light-and-dark contradictions, the movie just has him shift personality modes. There’s no confrontation or introspection. Reeves (John Wick 2) gets an idea of a potentially menacing character but even he isn’t presented as an antagonist. The Dream is living large thanks to the cooperation of those in Comfort. He has a harem of willing ladies for breeding but he doesn’t seem dastardly. He’s like the grown-up rich kid throwing the party that everyone attends. Then there are near cameos by Giovanni Ribisi, Jim Carrey, and Diego Luna, which make you wonder why they ever showed up.

The characters just aren’t worth your attention and ultimately don’t matter in service of story or even a potential message. Arlen is much more of a figurehead than a person, and perhaps that’s why the director chose Waterhouse (Pride and Prejudice and Zombies) as her lead. The former model certainly makes a visually striking figure and knows how to arc her body in non-verbal ways to communicate feelings. However, I don’t know if there’s a good actress here. There’s no real reason to take away her arm and leg except that it looks cool and edgy. Initially it presents a visceral vulnerability for her and a disadvantage of escape, but after she arrives in Comfort, it’s as if she’s just any other able-bodied character. It feels like the director just liked the look and thought it would grab attention or say something meaningful. Momoa (Justice League) has a natural intimidating screen presence but he’s given so little to do. He’s just on glower autopilot. Miami Man is a killer and we watch him cook people’s limbs for some good eats. It’s almost like the movie wants you to forget this stuff when his paternal instincts kick in. Rather than embracing the light-and-dark contradictions, the movie just has him shift personality modes. There’s no confrontation or introspection. Reeves (John Wick 2) gets an idea of a potentially menacing character but even he isn’t presented as an antagonist. The Dream is living large thanks to the cooperation of those in Comfort. He has a harem of willing ladies for breeding but he doesn’t seem dastardly. He’s like the grown-up rich kid throwing the party that everyone attends. Then there are near cameos by Giovanni Ribisi, Jim Carrey, and Diego Luna, which make you wonder why they ever showed up.

The depressing part is that The Bad Batch starts off with a bang and had such potential. Amirpour is so assured early on and draws out the terror of Arlen’s plight in a gripping and satisfying manner. Her drifting is then met by a futile escape, and then we witness the relatively tasteful dismembering of our heroine. It’s disorienting but establishes the conflicts of the scene in a clear and concise fashion. The odds are against her and Arlen uses her captors underestimating her to supreme advantage. The opening twenty minutes are thrilling and well developed, presenting a capable protagonist and a dire threat. And then the movie just drops off the face of the Earth. I haven’t seen a movie self-sabotage an interesting start like this since perhaps Danny Boyle’s Sunshine. The first twenty minutes offer the audience a vantage point and set of goals. We’re learning about Arlen through her desperate and clever acts of survival. The rest of the movie is just bland wandering without any sense or urgency or purpose exhibited in that marvelous opening (hey, the amputated limbs special effects look nice).

Vacuous and increasingly monotonous, The Bad Batch valiantly tries to create an arty mood piece where it re-purposes genre pastiche into some kind of statement on the broken human condition. Or something. The story is so thinly written and the characters are too blank to register. They’re archetypes at best, walking accessories, pristine action figures given life and camera direction. It’s flash and surface-level quirks with distressed art direction. It feels like it’s trying so hard to be a cult movie at every turn. I’m certain that, not counting Keanu’s cult leader, there might only be 100 words spoken in the entire film. I feel like The Bad Batch is going to be a favorite for plenty of young teenagers that respond to its style and general sense of rebellion. Until, that is, they discover movies can have both style and substance.

Vacuous and increasingly monotonous, The Bad Batch valiantly tries to create an arty mood piece where it re-purposes genre pastiche into some kind of statement on the broken human condition. Or something. The story is so thinly written and the characters are too blank to register. They’re archetypes at best, walking accessories, pristine action figures given life and camera direction. It’s flash and surface-level quirks with distressed art direction. It feels like it’s trying so hard to be a cult movie at every turn. I’m certain that, not counting Keanu’s cult leader, there might only be 100 words spoken in the entire film. I feel like The Bad Batch is going to be a favorite for plenty of young teenagers that respond to its style and general sense of rebellion. Until, that is, they discover movies can have both style and substance.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Selma (2014)/ Black or White (2014)

There’s a reason that race is regarded as the “third rail” when it comes to American politics. A half-century after the marches and protests, chief among them the influence of Martin Luther King Jr., the world feels just as fractious as ever when it comes to race relations. The inauguration of America’s first black president was seen as a significant touchstone, but optimism has faded and recent headline-grabbing criminal cases, and the absence of indictments, have prompted thousands to voice their protest from assembly to street corner. Race relations are one of the thorniest issues today and will be for some time. Two recent films take two very different approaches to discussing race relations, and they’re clearly made for two very different audiences. Selma is an invigorating, moving, and exceptional film showcasing bravery and dignity. Where Selma is complex, Black or White is a simplified and misguided sitcom writ large.

There’s a reason that race is regarded as the “third rail” when it comes to American politics. A half-century after the marches and protests, chief among them the influence of Martin Luther King Jr., the world feels just as fractious as ever when it comes to race relations. The inauguration of America’s first black president was seen as a significant touchstone, but optimism has faded and recent headline-grabbing criminal cases, and the absence of indictments, have prompted thousands to voice their protest from assembly to street corner. Race relations are one of the thorniest issues today and will be for some time. Two recent films take two very different approaches to discussing race relations, and they’re clearly made for two very different audiences. Selma is an invigorating, moving, and exceptional film showcasing bravery and dignity. Where Selma is complex, Black or White is a simplified and misguided sitcom writ large.

In 1965, Alabama was the epicenter for the Civil Rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo) has his sights set on organizing a march from Selma to the sate capital in Montgomery. His wife, Coretta (Carmen Ejogo), is worried about the safety of their children, as death threats are sadly common for MLK. He needs to turn the tide of public perception to light a fire under President Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) to get him to prioritize legislation that would protect every citizen’s right to vote.

Without question, Selma is one of the finest films of 2014. It is powerful, resonant, nuanced, political, immediate, and generally excellent on all fronts. It’s a rarity in Hollywood, namely a movie about the Civil Rights movement without a prominent white savior. This is a film about the ordinary and famous black faces on the ground fighting in the trenches for their freedoms. There are compassionate white people who heed the call, don’t get me wrong, but this is a movie told from the black perspective. I suspect the portrayal of President Johnson had something to do with Selma’s poor showing with the Oscars, though I can’t fully comprehend why. Yes, Johnson is portrayed as a man who has to be won over, but he’s on MLK’s side from the beginning. He is not opposed to legislation to protect voting rights; he’s just hesitant about the timing. Johnson says, “You got one issue, I got 100,” and the pragmatic reality of pushing forward legislation through a divided Congress was real. Johnson was not opposed to MLK’s wishes; he just wanted him to wait until the political process would be easier. In fact, in my eyes, Johnson comes across as compassionate, politically savvy, and he clearly makes his stakes on which side of history he’s going to be associated when he has a sit-down with the obstinate Alabama governor, George Wallace (Tim Roth). Like the rest of the varied characters in Selma, it’s a nuanced portrayal of a man in the moment.

Without question, Selma is one of the finest films of 2014. It is powerful, resonant, nuanced, political, immediate, and generally excellent on all fronts. It’s a rarity in Hollywood, namely a movie about the Civil Rights movement without a prominent white savior. This is a film about the ordinary and famous black faces on the ground fighting in the trenches for their freedoms. There are compassionate white people who heed the call, don’t get me wrong, but this is a movie told from the black perspective. I suspect the portrayal of President Johnson had something to do with Selma’s poor showing with the Oscars, though I can’t fully comprehend why. Yes, Johnson is portrayed as a man who has to be won over, but he’s on MLK’s side from the beginning. He is not opposed to legislation to protect voting rights; he’s just hesitant about the timing. Johnson says, “You got one issue, I got 100,” and the pragmatic reality of pushing forward legislation through a divided Congress was real. Johnson was not opposed to MLK’s wishes; he just wanted him to wait until the political process would be easier. In fact, in my eyes, Johnson comes across as compassionate, politically savvy, and he clearly makes his stakes on which side of history he’s going to be associated when he has a sit-down with the obstinate Alabama governor, George Wallace (Tim Roth). Like the rest of the varied characters in Selma, it’s a nuanced portrayal of a man in the moment.

The march in Selma is a moment that seems like an afterthought in the narrative of the Civil Rights movement, dwarfed by the Montgomery bus boycott and the March on Washington. The movie does a great job of re-examining why this moment in history is as significant, an eye-opening moment for the nation to the brutal reality of oppression. The opposition is entrenched, thanks to a stagnant system that wants to hold onto its “way of life.” It just so happens that way of life meant very different things for black people. The movie is politically sharp, with dissenting perspectives arguing over the next course of action in Selma and the national stage. Selma is another in the current crop of biopics eschewing the standard cradle-to-grave approach to highlight a significant moment that highlights exactly who their central figure is (Lincoln, Invictus). With Selma, we get a battleground that allows us to explore in both micro and macro MLK, the man. The courage of ordinary citizens in the face of violent beatdowns and police bullying is effortlessly moving and often heartbreaking. There is a moment when an elderly man, reflecting upon a recent family tragedy, cannot find words to express his grief, and my heart just ached right then and there. I teared up at several points, I don’t mind saying.

There isn’t a moment where I didn’t feel that director Anna DuVernay (Middle of Nowhere) was taking the easy road or pulling her punches. The screenplay respects the intelligence of the audience to sift through the politics and the arguments, to recognize when MLK is igniting a spark, and just how complicated and fragile the Selma situation was back then. Here’s a movie ostensibly about MLK but spends much of its time on the lesser known individuals like James Bevel and Congressman John Lewis, who walked alongside the man, taking time to flesh them out as people rather than plot points. MLK’s wife is also given an important part to play and she’s much more than just being the Wife of Great Man. DuVernay’s direction is impeccable; you feel like she has command over every frame. The sun-dappled cinematography by Bradford Young (A Most Violent Year) makes great use of shadows, often bathing its subjects in low-light settings. The score is rousing without being overpowering, just like every other technical aspect. This is a prime example of Hollywood filmmaking with vision and drive.

There isn’t a moment where I didn’t feel that director Anna DuVernay (Middle of Nowhere) was taking the easy road or pulling her punches. The screenplay respects the intelligence of the audience to sift through the politics and the arguments, to recognize when MLK is igniting a spark, and just how complicated and fragile the Selma situation was back then. Here’s a movie ostensibly about MLK but spends much of its time on the lesser known individuals like James Bevel and Congressman John Lewis, who walked alongside the man, taking time to flesh them out as people rather than plot points. MLK’s wife is also given an important part to play and she’s much more than just being the Wife of Great Man. DuVernay’s direction is impeccable; you feel like she has command over every frame. The sun-dappled cinematography by Bradford Young (A Most Violent Year) makes great use of shadows, often bathing its subjects in low-light settings. The score is rousing without being overpowering, just like every other technical aspect. This is a prime example of Hollywood filmmaking with vision and drive.

With respect to the Academy, it’s hard for me to imagine there being five better performances than the one Oyelowo (Lee Daniels’ The Butler) delivers as the indomitable Martin Luther King Jr. It is rare to see an actor inhabit his or her character so completely, and Oyelowo just sinks into the skin of this man. You never feel like you’re watching an actor but the living embodiment of history made flesh. This is a complex performance that shows refreshing degrees of humanity for a figure sanctified. He was a man first and foremost, and one prone to doubts and weaknesses as well. An excellent scene with top-notch tension and peak emotion involves MLK and Coretta listening to a supposed tape of Martin’s infidelity. In the ensuing tense conversation, both parties acknowledge the reality of his affairs. It’s a scene that’s underplayed, letting the audience know she knows, and he knows she knows, but not having to rely upon large histrionics and confrontations. It’s the behind-the-scenes moments with King that brought him to life for me, watching him coordinate and plan where to go with the movement. Oyelowo perfectly captures his fiery inspirational side, knocking out every single speech with ease. It’s a performance of great nuance and grace, where you see the fear in the man’s eyes as he steps forward, hoping he’s making the best decision possible for those in desperation.