Blog Archives

Opus (2025)

Ever want to watch a second-rate version of The Menu and be left wondering why you didn’t just watch The Menu? That was my main takeaway watching the indie horror/comedy (?) Opus, a darkly satirical look at the music industry and specifically cults of personality. John Malkovich plays Alfred Moretti, an exalted and reclusive musical genius who has earned numerous awards and built a devoted fandom. He’s invited six special guests to a listening party for his new album, the first since his mysterious retirement. It just so happens that party is at his compound and the guests are tended to by a cult of devotees. From there, people start to go missing and weirdness ensues. I was waiting throughout the entirety of Opus for something, anything to really grab me. These are good actors. It’s a premise that has potential. Alas, the movie is uneven and under developed and I found my interest draining the longer it went. The music satire isn’t specific or sharp enough to draw blood or genuine laughs. The weirdness of life on the compound is pretty bland, with the exception of a museum devoted to Moretti’s childhood home that is explored during the climax. The characters are too stock and boring, not really even succeeding as industry send-ups. The music itself is also pretty lackluster, but the movie doesn’t have the courage to argue that the cult has formed around a hack. In the world of Opus, Moretti is an inarguable musical genius. We needed the main character, played by Ayo Edebiri (The Bear), to be an agnostic, someone who doesn’t get the appeal of this musical maven and can destruct his pomposity. Alas, the obvious horror dread of the followers being a murder cult is never given more thought. It’s fine that Opus has familiar horror/cult elements (The Menu, Midsommar, Blink Twice, etc.) but it doesn’t do anything different or interesting with them. It’s obvious and dull without any specific personality to distinguish itself, and if maybe that was the argument against the cult leader, I might see a larger creative design. Instead, it all feels so listless. When the weird cult movie can’t even work up many weird details about its weird cult, then you’re watching a movie that is confused about themes and genre.

Ever want to watch a second-rate version of The Menu and be left wondering why you didn’t just watch The Menu? That was my main takeaway watching the indie horror/comedy (?) Opus, a darkly satirical look at the music industry and specifically cults of personality. John Malkovich plays Alfred Moretti, an exalted and reclusive musical genius who has earned numerous awards and built a devoted fandom. He’s invited six special guests to a listening party for his new album, the first since his mysterious retirement. It just so happens that party is at his compound and the guests are tended to by a cult of devotees. From there, people start to go missing and weirdness ensues. I was waiting throughout the entirety of Opus for something, anything to really grab me. These are good actors. It’s a premise that has potential. Alas, the movie is uneven and under developed and I found my interest draining the longer it went. The music satire isn’t specific or sharp enough to draw blood or genuine laughs. The weirdness of life on the compound is pretty bland, with the exception of a museum devoted to Moretti’s childhood home that is explored during the climax. The characters are too stock and boring, not really even succeeding as industry send-ups. The music itself is also pretty lackluster, but the movie doesn’t have the courage to argue that the cult has formed around a hack. In the world of Opus, Moretti is an inarguable musical genius. We needed the main character, played by Ayo Edebiri (The Bear), to be an agnostic, someone who doesn’t get the appeal of this musical maven and can destruct his pomposity. Alas, the obvious horror dread of the followers being a murder cult is never given more thought. It’s fine that Opus has familiar horror/cult elements (The Menu, Midsommar, Blink Twice, etc.) but it doesn’t do anything different or interesting with them. It’s obvious and dull without any specific personality to distinguish itself, and if maybe that was the argument against the cult leader, I might see a larger creative design. Instead, it all feels so listless. When the weird cult movie can’t even work up many weird details about its weird cult, then you’re watching a movie that is confused about themes and genre.

Nate’s Grade: C-

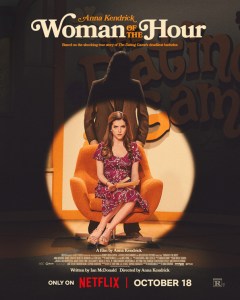

Woman of the Hour (2024)

I never knew there was an actual serial killer that appeared on a 1978 episode of The Dating Game, and that he actually won. That’s a killer hook. The problem with Woman of the Hour, Anna Kendrick’s debut as a director, is that there isn’t really a movie here as presented. Because the game show segment can only last so long, we get the creepy first date, that never happened in real life, and watch Kendrick playing our lucky lady with mounting dread. A moment where the killer requests that she re-read the phone number she hastily gave him by memory, because she should know her number, is terrifically tense, as is the scene of him following her to her car. The problem is that this first date can only last so long, just as the cheesy TV game show segment can only last so long, so the movie has to provide extra back-story to fill the time. We get several past encounters with the killer’s unfortunate victims, all played quite unnervingly and seriously. The woman of the hour is less Kendrick getting her fleeting spotlight on TV, and an anecdote to impress people at parties for the rest of her life, than the survivor who eventually leads to the killer’s arrest. Amazingly, at the time of his TV appearance, he was on the FBI’s Most Wanted List but there wasn’t a searchable database, so he clumsily got to keep committing murders, including while out on bail. It’s a harrowing story, but is it one best told through the gimmick structure of the game show appearance? If you were going this route, perhaps best to treat the material like a slow-burn stage play, starting with the first date, and watch in real time as it gets awkward and our heroine begins to have her suspicions that this man does not mean her well. Instead, the game show segments are goofy and broad and the least important moments in the stretched-thin film. There might be a movie with this subject, but I’m not sure that Woman of the Hour is it.

I never knew there was an actual serial killer that appeared on a 1978 episode of The Dating Game, and that he actually won. That’s a killer hook. The problem with Woman of the Hour, Anna Kendrick’s debut as a director, is that there isn’t really a movie here as presented. Because the game show segment can only last so long, we get the creepy first date, that never happened in real life, and watch Kendrick playing our lucky lady with mounting dread. A moment where the killer requests that she re-read the phone number she hastily gave him by memory, because she should know her number, is terrifically tense, as is the scene of him following her to her car. The problem is that this first date can only last so long, just as the cheesy TV game show segment can only last so long, so the movie has to provide extra back-story to fill the time. We get several past encounters with the killer’s unfortunate victims, all played quite unnervingly and seriously. The woman of the hour is less Kendrick getting her fleeting spotlight on TV, and an anecdote to impress people at parties for the rest of her life, than the survivor who eventually leads to the killer’s arrest. Amazingly, at the time of his TV appearance, he was on the FBI’s Most Wanted List but there wasn’t a searchable database, so he clumsily got to keep committing murders, including while out on bail. It’s a harrowing story, but is it one best told through the gimmick structure of the game show appearance? If you were going this route, perhaps best to treat the material like a slow-burn stage play, starting with the first date, and watch in real time as it gets awkward and our heroine begins to have her suspicions that this man does not mean her well. Instead, the game show segments are goofy and broad and the least important moments in the stretched-thin film. There might be a movie with this subject, but I’m not sure that Woman of the Hour is it.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Inside Out 2 (2024)

Of all the Pixar hits, 2015’s Inside Out is one of the better movies to develop a sequel for, and thankfully Inside Out 2 is a solid extension from the original. The internal world of Riley’s burgeoning sense of self is so deeply imaginative and creatively rewarding, balancing slapstick and broad humor with a deeper examination of abstract concepts and human psychology (Freud would have loved this movie… or hated it… or just thought about his mother). The unique setting was made so accessible by the nimble screenplay that the viewer was able to learn the rules of this setting and how interconnected the various parts are. While not being as marvelously inventive as its predecessor, nor as poignant (R.I.P. Bing Bong), Inside Out 2 is a heartwarming and reaffirming animated movie that will work for all ages.

Riley is now turning thirteen years old and in the midst of puberty. That means new emotions, and Joy (voiced by Amy Poehler) has to learn to work well with her co-workers, such as Envy, Embarassment, and Ennui. The biggest new addition is Anxiety (voiced by Maya Hawke) who wants to prepare Riley for her life ahead, which seems especially rocky now that Riley knows her two best friends will be going to a different school. A weekend trip to hockey camp becomes Riley’s opportunity to test drive the “new Riley,” the one who impresses the cool older kids and gains their acceptance. This will force Riley to have to determine which set of friends to prioritize, the new or the old, and whether the goofy, kind version can survive to middle school or needs to be snuffed out.

With the sequel, there aren’t any dramatically new wrinkles to the world building already established. We don’t exactly discover any new portions of Riley’s mind, instead choosing to place most of the plot’s emphasis on another long journey back to home base. This time the other core emotions get to stick around with Joy, each of them proving useful during a key moment on the adventure. The externalization of the emotions invites the viewer to feel something toward feelings themselves. When Joy, at her lowest, laments that maybe a hard realization about growing up is that life will simply have less joy, it really hit me. Part of it was just the sad contemplation that accepting adulthood means accepting a life with less happiness, but a big part was teaching this concept to children and being unable to provide them the joy they deserve. Since the 2015 original, my life has gone through different changes and now I watch these movies not just as an individual viewer recalling life as a former adolescent figuring things out, but now I also come from the perspective of a parent with young children, including one turning thirteen. The development of the mind of this little growing person is a heavy responsibility given to people who are, hopefully, up to that very herculean task. We can all try our best, but recognizing limitations is also key. The kids have to have the freedom to be themselves and not pint-sized facsimiles of a parent.

The emotions inside Riley’s mind are featured like internal surrogate parents, tending to the development of Riley’s emotions, morals, and personality. They presumably want what’s best for her, there just happen to be opposing interpretations of what that exactly means, which leads to the majority of conflict with Anxiety. However, there’s also an understanding that Riley has to do things on her own and be able to make mistakes and learn from them. Inside Out 2 is ultimately about accepting the limitations of providing guidance. Joy and Anxiety are both trying to steer Riley down a deliberate path they think is best, but Riley needs to discover her own path rather than have it programmed for her. I appreciated that Anxiety is not treated as some dangerous one-dimensional villain hijacking Riley’s brain. Much like sadness, there is a real psychological purpose for anxiety, to keep us alert and prepared. Now that can certainly go into overdrive, as demonstrated throughout Inside Out 2, including a realistic depiction of a panic attack. It’s about finding balance, though one person’s balance will be inordinately different from another. The stakes may be intentionally low in this movie, all about making the hockey team and being welcomed by the popular girl she may or may not be crushing over (more on that later), but the focus is on the sense of who Riley chooses to be through her life’s inevitable ups and downs. It’s about our response to change as much as it is our response to the presence of anxiety.

Inside Out 2 also answers a thorny world-building question that the original creators never thought to go into greater detail. It’s established in the 2015 original that even the adults have the same five core emotions manning their brain battle stations: Disgust, Fear, Sadness, Anger, and Joy. So if adults only see these same emotions, what happens to those new puberty emotions? Do they go away? As an adult, do we gradually work through anxiety and embarrassment to the point where they are no longer present (this is where every adult can wryly laugh)? There’s an emotion introduced as Nostalgia, depicted as a kindly grandmother so eager to remember the ways things were. Joy tells Nostalgia to leave, as it’s not time for her to be developed yet until Riley is older. This one moment clears up the world-building question; the emotions don’t leave, they just sit out for periods of time like bench players waiting to be called into the big game. And just like that, it all works and makes sense. I wonder what other new emotions make their appearances later in life. Resentment? Choosing to rather die in authority rather than give up an iota of power to a younger generation? Sorry, that last one was more directed at those stubborn folks clinging to Congressional offices.

There is some sight narrative and thematic redundancy here. The first movie was about learning the importance of accepting sadness as a vital part of the human condition and how we can process our emotional states. It was about Joy learning that not every moment in life can or should be dominated by joy, and that the other emotions are also necessary functions. With the sequel, we have a starting point where Joy is picking and choosing what memories are worthy of being remembered, banishing the “bad moments” to the back of Riley’s mind, forming a cavernous landfill of junked memories. It’s treading some pretty similar ground, prioritizing one set of memories or emotions over others wherein the ultimate lesson is that repression in all forms is unhealthy and robbing one of the necessary tools for self-acceptance and growth. This is further epitomized by a trip to one of these memory vaults where Riley’s Deep Dark Secret is willfully imprisoned. The movie proper never comes back to this self-loathing figure, and the revelation could have really supported the overall message of self-acceptance. Pixar could have done something really special here, like having Riley coming to terms with being bisexual/queer, and that perhaps something we may personally agonize over as a horrifying secret could, once shared, be far from the dreaded life-destroying culprit our minds make it out to be. This would have really worked with the perceived lower stakes of the movie, naturally elevating the ordinary to the profound, as life can often unexpectedly become. Alas, the Deep Dark Secret is just a setup to an underwhelming post-credits joke – womp womp. That’s it? Again, if you’re going to tread the familiar thematic grounds about the dangers of repression, at least give us something bigger to reach than the same lesson that all emotions have a place.

The first Inside Out was a masterpiece. That’s a hard act to follow. This sequel, of which we can all assume there will be more given its billion-dollar box-office, is a solid double to the original’s home run of entertainment. It’s not among their best but it’s one of their better non-Toy Story sequels. Inside Out 2 is a heartwarming winner.

Nate’s Grade: B

Clifford the Big Red Dog (2021)

What can one expect from the 80-minute live-action feature film of a children’s book series that was about a giant red dog? While ostensibly made for little kids, like those strictly under ten, Clifford the Big Red Dog (not to be confused with the equally alarming Clifford) is banal entertainment that’s inoffensive as long as you don’t have a deep personal attachment to the best-selling source material. It’s your standard children’s fantasy come alive with a giant dog that needs to be cared for as well as kept a secret. There are rambunctious moments of quelling the dog, mischievous moments of chasing the dog, and frantic moments of running away from a gene-splicing tech guru (Tony Hale). And oh, you bet there is scatological humor. We got dog farts. We got dog butt humor. We got dog pee. We got dog poop, at least in reference though thankfully never seen. I don’t know why we needed an added story of a little girl struggling to fit in at middle school with preppy, mean girls. I guess because a big red dog is also struggling to fit in? For that matter, the movie never returns to the opening scene of Clifford’s dog family being taken from him (a baffling and sad opening). There’s a more charming, heartfelt movie somewhere in here, akin to a Paddington where the central character changes those around them for the better, but our little New York City neighborhood is strictly in a more plastic and safe world. There are a few jokes that slipped past and made me laugh, so it’s not all a loss. Clifford doesn’t pretend to be anything more or less than its meagerly stated goals, and it’s a serviceable family film as long as your little ones have a low threshold for realistic-looking CGI dogs.

What can one expect from the 80-minute live-action feature film of a children’s book series that was about a giant red dog? While ostensibly made for little kids, like those strictly under ten, Clifford the Big Red Dog (not to be confused with the equally alarming Clifford) is banal entertainment that’s inoffensive as long as you don’t have a deep personal attachment to the best-selling source material. It’s your standard children’s fantasy come alive with a giant dog that needs to be cared for as well as kept a secret. There are rambunctious moments of quelling the dog, mischievous moments of chasing the dog, and frantic moments of running away from a gene-splicing tech guru (Tony Hale). And oh, you bet there is scatological humor. We got dog farts. We got dog butt humor. We got dog pee. We got dog poop, at least in reference though thankfully never seen. I don’t know why we needed an added story of a little girl struggling to fit in at middle school with preppy, mean girls. I guess because a big red dog is also struggling to fit in? For that matter, the movie never returns to the opening scene of Clifford’s dog family being taken from him (a baffling and sad opening). There’s a more charming, heartfelt movie somewhere in here, akin to a Paddington where the central character changes those around them for the better, but our little New York City neighborhood is strictly in a more plastic and safe world. There are a few jokes that slipped past and made me laugh, so it’s not all a loss. Clifford doesn’t pretend to be anything more or less than its meagerly stated goals, and it’s a serviceable family film as long as your little ones have a low threshold for realistic-looking CGI dogs.

Nate’s Grade: C, for Clifford

Nine Days (2021)

Oddly enough, over the course of less than a year, we now have two movies about young souls competing to find their sense of self before being born. Will (Winston Duke) lives in a small cottage in the middle of the desert. Or so it would appear. He’s a former human who now serves as a spirit who watches over the lives of a select group of others on Earth through P.O.V. monitors. After a car accident, one of his people is killed, leaving a new opening. It’s Will’s job to interview a group of candidates and determine who is best equipped to handle being born. Will takes the process very seriously but he is also more emotionally affected by the loss of life under his guidance than he admits. Where did he go wrong, or is right and wrong even the right markers for assessment? Will must choose wisely over nine days of deliberation and insight into what it means to be human and what it means to live.

Oddly enough, over the course of less than a year, we now have two movies about young souls competing to find their sense of self before being born. Will (Winston Duke) lives in a small cottage in the middle of the desert. Or so it would appear. He’s a former human who now serves as a spirit who watches over the lives of a select group of others on Earth through P.O.V. monitors. After a car accident, one of his people is killed, leaving a new opening. It’s Will’s job to interview a group of candidates and determine who is best equipped to handle being born. Will takes the process very seriously but he is also more emotionally affected by the loss of life under his guidance than he admits. Where did he go wrong, or is right and wrong even the right markers for assessment? Will must choose wisely over nine days of deliberation and insight into what it means to be human and what it means to live.

Nine Days is a tender and thoughtful movie that has much under the surface given its metaphysical context and probing questions about spirituality, identity, and existence, but it doesn’t simply rely upon the artistic weight of ambiguity. There’s a genuinely involving emotional drama here that’s accessible while offering greater depth to be unpacked by the viewer who enjoys metaphor and implication and debate. At its essence, the movie is about a series of job interviews but for a position that we don’t fully understand what the requirements are and if even meeting the requirements is enough for the hire. It’s a primarily dialogue-driven procedure but it’s also character-focused as the entire process examines what animates Will, what haunts him, and why he does what he does. Early on, the surreal nature of what should be an ordinary event, job candidates interviewing with a boss, gives the movie an air of mystery and offbeat humor. The candidates are showing up, going through a series of questions and role play scenarios, and with each session, the candidates evolve into the personas that will define them. There’s something mildly profound about watching the development of an identity before it’s even been born. As the movie progresses, Will turns down candidates and the news is truly devastating. Not only will these spirits/souls miss out on being born on Earth, they will cease to ever exist and fade away. That is some heavy stuff. Watching each one come to terms with that sort of death can be heartrending. Just imagining having to accept the end before life ever even began.

Nine Days is a tender and thoughtful movie that has much under the surface given its metaphysical context and probing questions about spirituality, identity, and existence, but it doesn’t simply rely upon the artistic weight of ambiguity. There’s a genuinely involving emotional drama here that’s accessible while offering greater depth to be unpacked by the viewer who enjoys metaphor and implication and debate. At its essence, the movie is about a series of job interviews but for a position that we don’t fully understand what the requirements are and if even meeting the requirements is enough for the hire. It’s a primarily dialogue-driven procedure but it’s also character-focused as the entire process examines what animates Will, what haunts him, and why he does what he does. Early on, the surreal nature of what should be an ordinary event, job candidates interviewing with a boss, gives the movie an air of mystery and offbeat humor. The candidates are showing up, going through a series of questions and role play scenarios, and with each session, the candidates evolve into the personas that will define them. There’s something mildly profound about watching the development of an identity before it’s even been born. As the movie progresses, Will turns down candidates and the news is truly devastating. Not only will these spirits/souls miss out on being born on Earth, they will cease to ever exist and fade away. That is some heavy stuff. Watching each one come to terms with that sort of death can be heartrending. Just imagining having to accept the end before life ever even began.

Rather than simply fade away into the blank of nothingness, Will chooses to help these souls get one last moment of peace before their ultimate end. He becomes a celestial one-man Make-A-Wish spiritual service. It’s unknown whether these “positive memories” are from the souls’ own development or their observation of the souls that have been placed on Earth. Regardless, each rejected candidate gets a moment that Will studiously recreates as an act of kindness. This section can be rather moving as each soul gets a personal sendoff and, in those final moments to savor, we watch them become affected with the generosity and the fleeting moment of life that will be tragically denied to them. One candidate climbs aboard a stationary bicycle, and Will positions one screen after another, each with projection from that angle of the street. When taken together, it creates the illusion of a nice bicycle ride through a town square. The homemade production, even sprinkling cherry blossoms and a swinging light to illustrate a traveling through a tunnel, provide small moments of affectionate conviction. I found each of these moments to be emotionally rich and beautifully rendered on screen. The care and craft Will puts into these acts is wonderful and a tremendous insight into who he is as a character and what he values in others.

Will is haunted by the idea that he may have been oblivious to the pain of one of his pupils, and this indecision is coloring his interview process for a replacement soul. It’s unclear what exactly Will is, or his boss, or his duties, but he vaguely amounts to a guardian angel. He has a bank of old TVs that he monitors and obsessively documents the lives of a few. He takes particular pride in one soul on Earth and listens to her virtuoso violin playing as a means of personal relaxation. Her sudden death rocks him, and when it’s revealed that she was depressed, he tries to make sense of being able to see and hear everything these souls do but not fully knowing them. Did he get something wrong in his clerical assessment? Did his understanding of her have its limits? Could she have been hiding something so all-consuming without his suspicion? It all upends Will and fosters self-doubt. He’s trying to make sense of something that may not ever make sense. That is how inscrutable human beings can be and how tragically fleeting life can become in an instant.

Will is haunted by the idea that he may have been oblivious to the pain of one of his pupils, and this indecision is coloring his interview process for a replacement soul. It’s unclear what exactly Will is, or his boss, or his duties, but he vaguely amounts to a guardian angel. He has a bank of old TVs that he monitors and obsessively documents the lives of a few. He takes particular pride in one soul on Earth and listens to her virtuoso violin playing as a means of personal relaxation. Her sudden death rocks him, and when it’s revealed that she was depressed, he tries to make sense of being able to see and hear everything these souls do but not fully knowing them. Did he get something wrong in his clerical assessment? Did his understanding of her have its limits? Could she have been hiding something so all-consuming without his suspicion? It all upends Will and fosters self-doubt. He’s trying to make sense of something that may not ever make sense. That is how inscrutable human beings can be and how tragically fleeting life can become in an instant.

The other change agent for Will is the presence of Emma (Zazie Beetz), a candidate who shows up late, questions the nature of the questions she is given, and is empathetic to a fault. The other candidates are playing within the rules of Will’s questions but she’s pushing back, and it only makes Will think more and more about her and her aims. I don’t consider it too much of a spoiler that Emma will be one of two final candidates for the open spot for life. Her character causes Will to reassess his own biases, his own way of doing things as they have, and his own conception of himself and what life can be about including his own time spent on Earth, which he likes to remind the others like it’s bragging rights. I suppose one could argue that, yet again, we have a quirky female character in service of teaching the male hero about the importance of embracing life to the fullest, but I think the general makeup of the characters is superfluous to the impact of the story. We’re dealing with spirits taking a physical form here. Their appearance is immaterial to their identity at this point, at least in an otherworldly realm that (hopefully) knows no sexism and racism.

Nine Days is the film debut from commercial director Edson Oda and the movie is utterly gorgeous from a technical standpoint. The photography favors gleaming sunsets and pristine vistas to communicate the exquisiteness and otherworldly plane of existence. The desert landscape is beautifully filmed, and the interiors are also pleasing with their visual arrangements and the mingling of natural and artificial light. Oda won a screenwriting award at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and for good measure. This isn’t just a good-looking indie, which it assuredly is, but there is deep melancholy and beauty and transcendence to be had with the very humane and compassionate storytelling trying to get at larger truths about our limited time. The storytelling has plenty of ambiguity and nuance and metaphor, but there’s an accessible core that I believe most viewers can align with and then, if they choose, can discover further meaning. There is a slightly basic “stop and smell the roses” moral, but I found there to be more lyrical beauty at different points that affected me deeper than any condensed message. The conclusion hinges on a recitation of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and it conveys not just Whitman’s celebratory humanism but also taps into Will’s own character arc. The poetic performance itself is an expression with multiple levels, celebrating life in multiple ways, and serving as a heartfelt and personal goodbye. It’s a lovely ending for a lovely little movie.

Nine Days is the film debut from commercial director Edson Oda and the movie is utterly gorgeous from a technical standpoint. The photography favors gleaming sunsets and pristine vistas to communicate the exquisiteness and otherworldly plane of existence. The desert landscape is beautifully filmed, and the interiors are also pleasing with their visual arrangements and the mingling of natural and artificial light. Oda won a screenwriting award at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival and for good measure. This isn’t just a good-looking indie, which it assuredly is, but there is deep melancholy and beauty and transcendence to be had with the very humane and compassionate storytelling trying to get at larger truths about our limited time. The storytelling has plenty of ambiguity and nuance and metaphor, but there’s an accessible core that I believe most viewers can align with and then, if they choose, can discover further meaning. There is a slightly basic “stop and smell the roses” moral, but I found there to be more lyrical beauty at different points that affected me deeper than any condensed message. The conclusion hinges on a recitation of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” and it conveys not just Whitman’s celebratory humanism but also taps into Will’s own character arc. The poetic performance itself is an expression with multiple levels, celebrating life in multiple ways, and serving as a heartfelt and personal goodbye. It’s a lovely ending for a lovely little movie.

Nine Days is packed with recognizable acting faces (Tony Hale, Bill Skarsgaard), several of whom have graced Marvel superhero movies (Duke, Beetz, Benedict Wong), and there must have been something compelling for them to all accept this low-budget, contemplative indie about the human condition. It’s a little movie with a lot on its mind but it doesn’t feel the need to explain everything. There’s a sturdy foundation to begin with but enough ambiguous room for discussion and debate. It reminds me of 2003’s beguiling, divisive, and highly metaphorical indie Northfork. Both movies are poetic, understated, and deeply involved in human connection and spiritual meaning while providing room for interpretation. There’s plenty here to unpack but even on a literal level the movie works as an emotional experience. I found myself under the gentle sway of Nine Days and its mighty beating heart of humanism that extends even beyond the realm of flesh and blood.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Toy Story 4 (2019)

The Toy Story franchise has been the gold standard for Pixar with three excellent movies, the last of which was released back in 2010. When the Pixar bigwigs announced they were making a fourth entry, I felt some degree of concern. The hidden world of toys still felt like an interesting world with more stories to be told, but did we need to revisit Woody and Buzz and the gang? Everything ended so beautifully and perfectly with the third movie, with the toys getting their sendoff from their original owner and a new life in the possession of a new child, little Bonnie. I’ve been more wary about this movie than just about any other Pixar film because the audience had something that could be lost, namely closure. If they harmed that perfect ending in the crass desire to extend the franchise for an extra buck, it would have been aggravating and depressing to disturb something that felt so complete. It’s like when Michael Jordan came out of retirement (the second time) to be a shadow of himself for the Washington Wizards in order to sell tickets for the team he was part owner of. Nobody wanted that. I’m happy to report that Toy Story 4 is a treat of a movie and a worthy addition to the franchise.

The Toy Story franchise has been the gold standard for Pixar with three excellent movies, the last of which was released back in 2010. When the Pixar bigwigs announced they were making a fourth entry, I felt some degree of concern. The hidden world of toys still felt like an interesting world with more stories to be told, but did we need to revisit Woody and Buzz and the gang? Everything ended so beautifully and perfectly with the third movie, with the toys getting their sendoff from their original owner and a new life in the possession of a new child, little Bonnie. I’ve been more wary about this movie than just about any other Pixar film because the audience had something that could be lost, namely closure. If they harmed that perfect ending in the crass desire to extend the franchise for an extra buck, it would have been aggravating and depressing to disturb something that felt so complete. It’s like when Michael Jordan came out of retirement (the second time) to be a shadow of himself for the Washington Wizards in order to sell tickets for the team he was part owner of. Nobody wanted that. I’m happy to report that Toy Story 4 is a treat of a movie and a worthy addition to the franchise.

Bonnie is gearing up for kindergarten and nervous about the change. She isn’t allowed to take toys with her to school, though that doesn’t stop Woody (voiced by Tom Hanks) from tagging along. In her desire for a friend, and with a little assist from a certain cowboy, Bonnie creates a fork-figure named Forky (Tony Hale), and amazingly it comes to life. Woody tries valiantly to convince Forky that being a toy to a child is the greatest gift but he’s also really reminding himself now that he sees his influence waning with Bonnie as he’s selected for play time less and less. During a family road trip, Forky escapes and Woody leaps to find him, both of them coming into the clutches of Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks), an antique doll missing a functional voice box who has her sights set on Woody’s voice box. It’s at this small-town pit stop for a carnival that Woody discovers Bo Peep (Annie Potts), an old flame he never thought he would see again. She’s assured, happy, and preaching a life of being independent from a kid. Woody has defined himself for so long by one identity, and now he must decide which to follow.

In many ways, Toy Story 4 takes themes and questions from the third movie and improves upon them, making what could have been a retread feel like a do-over you didn’t know you desired. It’s been many years since I saw the third film but I recall the major themes being the fear of change, reconciling one’s self-identity, and the courage of letting go and starting over. The toys had to recognize that their owner was growing up and their old place wasn’t going to be the same. This same issue finds new life in Toy Story 4 primarily through the lens of Woody, who finds himself on the decline with his kid’s interest. He’s not offended or upset by this but is still trying to provide what assistance he can as a beloved toy, even if that relationship becomes more and more one-sided. His identity is in selfless sacrifice for another, but with the re-emergence of Bo, he is now contemplating a life on his own, a life without a kid. This alternate path never seemed a possibility until his former flame stepped back into his life. It challenged Woody in a way that feels more personal and more relevant than it did with 3, especially with the removal of a larger external threat to occupy the attention of our main characters. This places a renewed focus on Woody’s internal dilemma beyond his role as leader and protector.

In many ways, Toy Story 4 takes themes and questions from the third movie and improves upon them, making what could have been a retread feel like a do-over you didn’t know you desired. It’s been many years since I saw the third film but I recall the major themes being the fear of change, reconciling one’s self-identity, and the courage of letting go and starting over. The toys had to recognize that their owner was growing up and their old place wasn’t going to be the same. This same issue finds new life in Toy Story 4 primarily through the lens of Woody, who finds himself on the decline with his kid’s interest. He’s not offended or upset by this but is still trying to provide what assistance he can as a beloved toy, even if that relationship becomes more and more one-sided. His identity is in selfless sacrifice for another, but with the re-emergence of Bo, he is now contemplating a life on his own, a life without a kid. This alternate path never seemed a possibility until his former flame stepped back into his life. It challenged Woody in a way that feels more personal and more relevant than it did with 3, especially with the removal of a larger external threat to occupy the attention of our main characters. This places a renewed focus on Woody’s internal dilemma beyond his role as leader and protector.

Toy Story 4 might also be the weirdest movie of the franchise, which really elevates the comedy into another realm. I thought the characters played by Jordan Peele (Us) and Keegan Michael-Key (Predator) were going to quickly wear out their welcome; they seemed to be a heavy part of pre-release teaser trailers. The filmmakers don’t overdo them and use them in clever ways, which is a compliment that can be applied to every new character in this sequel. The plushies by Key and Peele have a hilarious running gag of their increasingly absurd plans to attack a woman, and one instance deliciously prolongs the eventual punchline, becoming more bizarre and macabre to the point that I lost control from laughter. Keanu Reeves (John Wick 3) is fun as a very Canadian Evel Knievel motorcycle driver, and the weird references to the Canada-ness of it are played completely straight, making it even funnier (his laments with the French-Canadian boy’s name made me snicker every time). There’s a trio of action figures, Combat Carls, and one of the three is always left hanging for high-fives and he just leaves his arm up waiting, silently pleading, and then lowers it in defeat, and it’s hysterical even just as a background gag. The ventriloquist dummies are routinely played for creepy laughs and physical humor. There’s a running joke where Buttercup, the unicorn voiced by Jeff Garlin, is always suggesting getting Bonnie’s father sent to jail no matter the circumstances. It’s these touches of weirdness that make the movie stand out that much more from the three others.

The villain of Toy Story 4 is given a surprising sense of poignancy, enough that I genuinely sympathized with her plight. She’s a damaged doll used to being behind glass, isolated and separated from the children she wishes to be part of. She views her salvation in fixing in her damaged voice box, her perceived disability. She’s after what Woody has physically, the voice box, but it’s a means to an ends to have what Woody has had emotionally, the love of a child in need, the connection she yearns for. I won’t spoil what happens with her but even when there are setbacks the film and the characters don’t give up on Gabby Gabby. Her perspective and desires are still seen as valued, and the eventual resolution of her character put a lump in my throat. She wasn’t really the villain after all. She was just another toy in pain looking for acceptance and having to adjust her identity. I feel like there is a conscious disability empowerment message implanted in Toy Story 4, namely that those who are disfigured, disabled, or seen as “broken” can continue to be valuable and that their lives don’t end.

The villain of Toy Story 4 is given a surprising sense of poignancy, enough that I genuinely sympathized with her plight. She’s a damaged doll used to being behind glass, isolated and separated from the children she wishes to be part of. She views her salvation in fixing in her damaged voice box, her perceived disability. She’s after what Woody has physically, the voice box, but it’s a means to an ends to have what Woody has had emotionally, the love of a child in need, the connection she yearns for. I won’t spoil what happens with her but even when there are setbacks the film and the characters don’t give up on Gabby Gabby. Her perspective and desires are still seen as valued, and the eventual resolution of her character put a lump in my throat. She wasn’t really the villain after all. She was just another toy in pain looking for acceptance and having to adjust her identity. I feel like there is a conscious disability empowerment message implanted in Toy Story 4, namely that those who are disfigured, disabled, or seen as “broken” can continue to be valuable and that their lives don’t end.

If this serves as the finale of the franchise, it will end on a fitting and resonant high-point. As much as Toy Story 3 was about change and acceptance, this sequel does a very respectable effort of personalizing that message even more to one central character’s dramatic arc. It also works wonderfully playing off of our collective investment in the character over the course of four movies and twenty-four years. There are some drawbacks to this approach. It makes the majority of the other toy characters feel like they have little to do on the sidelines, other than fret about retrieving Woody and Forky. Buzz is given a cute joke about listening to his inner voice but it doesn’t amount to much more than a cute joke. The inclusion of Forky feels like an exciting and even daring addition, tackling some existential questions and how and when toys are “made” and brought into being, and he presents these for a while. Once we get to our carnival setting and Forky is captured, he seems to be forgotten about. He’s more a motivation point for Woody than overtly anything else. I suppose you could make the analysis that Forky represents how Bonnie is moving on even with invented toys at the expense of Woody. However, these are minor quibbles considering the quality and emotional involvement of what Pixar has produced.

It goes without saying that the animation is beautiful but what amazed me is how expressive the faces of the characters could be, even when they were relatively inflexible toys. The relationship between Woody and Bo actually has a surprising amount of nonverbal dramatic acting to communicate nuance. As the years go by, I continue to be further and further amazed at the Pixar animators and their abilities.

As protective I was over Toy Story 3’s perfect ending, I am happy to say that Toy Story 4 more than justifies its own existence in this hallowed franchise and even improves from the third film. The themes are something of a repeat but the filmmakers have elected to focus almost entirely on Woody and his personal journey, and it makes the loss and possibility more robustly felt. In many ways the film is an exploration on relationships and the need to redefine ourselves, to move onward when the time is right, and to try something new even if things get scary. Between Woody and Gabby Gabby, ostensibly the hero and villain of the piece, they’re looking for meaningful connections where they can. They may be secondhand, they may be disabled, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worthy of affection. This is a joyous movie that finds time to be wonderfully weird and often funny. It might not have the set pieces or ensemble showmanship of the prior Toy Story tales, but what it does have is a character-based emphasis on the most complex figure in this universe of toys. The conclusion is moving and satisfying and I don’t mind admitting that tears were shed. I even teared up at different other earlier points. Toy Story 4 could have gone a lot of different ways but I’m relieved and appreciative with this new sendoff we’ve been granted.

As protective I was over Toy Story 3’s perfect ending, I am happy to say that Toy Story 4 more than justifies its own existence in this hallowed franchise and even improves from the third film. The themes are something of a repeat but the filmmakers have elected to focus almost entirely on Woody and his personal journey, and it makes the loss and possibility more robustly felt. In many ways the film is an exploration on relationships and the need to redefine ourselves, to move onward when the time is right, and to try something new even if things get scary. Between Woody and Gabby Gabby, ostensibly the hero and villain of the piece, they’re looking for meaningful connections where they can. They may be secondhand, they may be disabled, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worthy of affection. This is a joyous movie that finds time to be wonderfully weird and often funny. It might not have the set pieces or ensemble showmanship of the prior Toy Story tales, but what it does have is a character-based emphasis on the most complex figure in this universe of toys. The conclusion is moving and satisfying and I don’t mind admitting that tears were shed. I even teared up at different other earlier points. Toy Story 4 could have gone a lot of different ways but I’m relieved and appreciative with this new sendoff we’ve been granted.

Nate’s Grade: A

You must be logged in to post a comment.