Blog Archives

Trap (2024)

At this point, there is a certain expectation with any M. Night Shyamalan movie that reality will be heightened, that people will never talk like actual human beings, and that his brand of unreality can become part of the unique selling point, nestling into a campy charm when it all coalesces. Such is the case with Trap, the ludicrous thriller that plays much more pleasingly as a wacky comedy of errors and incompetence as an entire city’s police force is looking for a notorious serial killer, The Butcher a.k.a. Cooper (Josh Hartnett), at a concert for a pop star (Syamalan’s own daughter, Saleka). It’s a silly premise that essentially endangers thousands of innocent concert-goers where the plan is to, I guess, grab any middle-aged white guy in attendance and question them? It’s absurd, but it becomes a fun game of watching our trapped killer try and work out different escape options and adapt on the fly, while also being that supportive girl dad for his starstruck little tween. There’s an appealing “how is he gonna get outta this jam?” conflict resolution, though our deadly dad also acts so supremely weird, from buddying up with the merch guy, pushing ladies down stairs completely unbeknownst to observers, and trying to convince his daughter they should ditch this fancy concert to go explore what’s beneath a trap door. The hilarity is that Cooper is not really good at hiding his tracks, or his peculiarities, but everyone else in this universe is just that dim. It’s grand entertainment but definitely loses something once it leaves the central location for its final act, shifting the protagonist onto a new face that can’t quite carry the movie(reminded me of 2013’s The Call once it abandoned its premise for the final act). Given the heightened atmosphere, this is also the kind of movie that would have benefited from another twist or two, perhaps with Cooper’s family. Hartnett is playing a very specific tone and manages to make his character creepy, daffy, intense, and thoroughly watchable. If you’re in doubt what Shyamalan was going for, look no further than casting Parent Trap(!)-actress Hayley Mills as the older criminal psychologist trying to ensnare our killer with this outlandish ruse. Imagine Hitchcock by way of Peter Sellers, and you have Trap.

At this point, there is a certain expectation with any M. Night Shyamalan movie that reality will be heightened, that people will never talk like actual human beings, and that his brand of unreality can become part of the unique selling point, nestling into a campy charm when it all coalesces. Such is the case with Trap, the ludicrous thriller that plays much more pleasingly as a wacky comedy of errors and incompetence as an entire city’s police force is looking for a notorious serial killer, The Butcher a.k.a. Cooper (Josh Hartnett), at a concert for a pop star (Syamalan’s own daughter, Saleka). It’s a silly premise that essentially endangers thousands of innocent concert-goers where the plan is to, I guess, grab any middle-aged white guy in attendance and question them? It’s absurd, but it becomes a fun game of watching our trapped killer try and work out different escape options and adapt on the fly, while also being that supportive girl dad for his starstruck little tween. There’s an appealing “how is he gonna get outta this jam?” conflict resolution, though our deadly dad also acts so supremely weird, from buddying up with the merch guy, pushing ladies down stairs completely unbeknownst to observers, and trying to convince his daughter they should ditch this fancy concert to go explore what’s beneath a trap door. The hilarity is that Cooper is not really good at hiding his tracks, or his peculiarities, but everyone else in this universe is just that dim. It’s grand entertainment but definitely loses something once it leaves the central location for its final act, shifting the protagonist onto a new face that can’t quite carry the movie(reminded me of 2013’s The Call once it abandoned its premise for the final act). Given the heightened atmosphere, this is also the kind of movie that would have benefited from another twist or two, perhaps with Cooper’s family. Hartnett is playing a very specific tone and manages to make his character creepy, daffy, intense, and thoroughly watchable. If you’re in doubt what Shyamalan was going for, look no further than casting Parent Trap(!)-actress Hayley Mills as the older criminal psychologist trying to ensnare our killer with this outlandish ruse. Imagine Hitchcock by way of Peter Sellers, and you have Trap.

Nate’s Grade: B-

The Village (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released July 30, 2004:

Originally released July 30, 2004:

When saying director names you can play a fun little game of word association. Someone says, “George Lucas,” and things like big-budget effects, empty storytelling, and wooden dialogue come to mind. Someone says, “David Lynch,” and weird, abstract, therapy sessions dance in your head. The behemoth of word association is M. Night Shyamalan. He burst onto the scene with 1999’s blockbuster, The Sixth Sense, a crafty, moody, intelligent thriller with a knock-out final twist. Now, though, it seems more and more evident that while The Sixth Sense was the making of M. Night Shyamalan, it also appears to be his undoing. His follow-up films, Unbreakable and Signs, have suffered by comparison, but what seems to be hampering Shyamalan’s growth as a writer is the tightening noose of audience expectation that he kowtows to.

With this in mind, we have Shyamalan’s newest cinematic offering, The Village. Set in 1897, we follow the simple, agrarian lives of the people that inhabit a small secluded hamlet. The town is isolated because of a surrounding dense forest. Mythical creatures referred to as Those We Dont Speak Of populate the woods. An uneasy truce has been agreed upon between the creatures and the villagers, as long as neither camp ventures over into the others territory. When someone does enter the woods, foreboding signs arise. Animals are found skinned, red marks are found on doors, and people worry that the truce may be over. Within this setting, we follow the ordinary lives of the townsfolk. Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard) is the daughter of the towns self-appointed mayor (William Hurt), and doesn’t let a little thing like being blind get in the way of her happiness. She is smitten with Lucius (Joaquin Phoenix), a soft-spoken loner. Noah (Adrien Brody), a mentally challenged man, also has feelings for Ivy, which cause greater conflict.

Arguably, the best thing about The Village is the discovery of Howard. She proves herself to be an acting revelation that will have future success long after The Village is forgotten. Her winsome presence, wide radiant smile, and uncanny ability to quickly endear the character of Ivy to the audience. She is the only one onscreen with genuine personality and charisma, and when shes flirting and being cute about it you cannot help but fall in love with her. And when she is being torn up inside, the audience feels the same emotional turmoil. I am convinced that this is more so from Howard’s acting than from the writing of Shyamalan. She reminds me of a young Cate Blanchett, both in features and talent.

Arguably, the best thing about The Village is the discovery of Howard. She proves herself to be an acting revelation that will have future success long after The Village is forgotten. Her winsome presence, wide radiant smile, and uncanny ability to quickly endear the character of Ivy to the audience. She is the only one onscreen with genuine personality and charisma, and when shes flirting and being cute about it you cannot help but fall in love with her. And when she is being torn up inside, the audience feels the same emotional turmoil. I am convinced that this is more so from Howard’s acting than from the writing of Shyamalan. She reminds me of a young Cate Blanchett, both in features and talent.

It seems to me that Shyamalan’s directing is getting better with every movie while his writing is getting proportionately worse. He has a masterful sense of pacing and mood, creating long takes that give the viewer a sense of unease. The first arrival of the creatures is an expertly handled scene that delivers plenty of suspense, and a slow-motion capper, with music swelling, that caused me to pump my fist. The cinematography by Roger Deakins is beautifully elegant. Even the violin-heavy score by James Newton Howard is a great asset to the film’s disposition.

So where does the film go wrong and the entertainment get sucked out?

What kills is its incongruous ending. Beforehand, Shyamalan has built a somewhat unsettling tale, but when he finally lays out all his cards, the whole is most certainly not more than the sum of its parts. In fact, the ending is so illogical, and raises infinitely more questions than feeble answers, that it undermines the rest of the film. Unlike The Sixth Sense, the twist of The Village does not get better with increased thought.

Shyamalan’s sense of timing with his story revelations is maddening. He drops one twist with 30 minutes left in the film, but what’s even more frustrating is he situates a character into supposed danger that the audience knows doesn’t exist anymore with this new knowledge. The audience has already been told the truth, and it deflates nearly all the tension. It’s as if Shyamalan reveals a twist and then tells the audience to immediately forget about it.

Shyamalan also exhibits a problem fully rendering his characters. They are so understated that they don’t ever really jump from the screen. The dialogue is very stilted and flat, as Shyamalan tries to stubbornly fit his message to ye olde English vernacular (which brings about a whole other question when the film’s final shoe is dropped). Shyamalan also seems to strand his characters into soap opera-ish subplots involving forbidden or unrequited love. For a good hour or so, minus one sequence, The Village is really a Jane Austin story with the occasional monster.

Shyamalan also exhibits a problem fully rendering his characters. They are so understated that they don’t ever really jump from the screen. The dialogue is very stilted and flat, as Shyamalan tries to stubbornly fit his message to ye olde English vernacular (which brings about a whole other question when the film’s final shoe is dropped). Shyamalan also seems to strand his characters into soap opera-ish subplots involving forbidden or unrequited love. For a good hour or so, minus one sequence, The Village is really a Jane Austin story with the occasional monster.

The rest of the villagers don’t come away looking as good as Howard. Phoenix’s taciturn delivery seems to suit the brooding Lucius, but at other times he can give the impression of dead space. Hurt is a sturdy actor but can’t find a good balance between his solemn village leader and caring if sneaky father. Sigourney Weaver just seems adrift like she’s looking for butter to churn. Brody is given the worst to work with. His mentally-challenged character is a terrible one-note plot device. He seems to inexplicably become clever when needed.

The Village is a disappointment when the weight of the talent involved is accounted for. Shyamalan crafts an interesting premise, a portent sense of dread, and about two thirds of a decent-to-good movie, but as Brian Cox said in Adaptation, ”The last act makes the film. Wow them in the end, and you’ve got a hit. You can have flaws and problems, but wow them in the end, and you’ve got a hit.” It’s not that the final twists and revelations are bad; it’s that they paint everything that came before them in a worse light. An audience going into The Village wanting to be scared will likely not be pleased, and only Shyamalan’s core followers will walk away fully appreciating the movie. In the end, it may take a village to get Shyamalan to break his writing rut.

Nate’s Grade: C+

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

Usually in the M. Night Shyamalan narratives, 2004’s The Village is where the cracks first started to show in the filmmaker’s game. While 2000’s Unbreakable didn’t exactly reach the box-office successes of The Sixth Sense and Signs, it still earned $250 million worldwide and was definitely ahead of the cultural curve, introducing a grounded superhero story before the oncoming wave of superhero cinema. No, it was The Village that started the questioning over whether Shyamalan’s need for big twist endings was hampering his creativity. While still earning almost the exact same box-office as Unbreakable, The Village was seen with more hesitation, a cautionary tale about a filmmaker, as Matt Singer recently put it, flying a little too close to the sun. From here, Shyamalan entered his down period, from 2006’s Lady in the Water, to 2008’s The Happening, and the big-budget sci-fi misfits of 2010’s Last Airbender and 2013’s After Earth. This was the beginning of the general public becoming wise to Shyamalan’s tricks.

The real kicker is that, twenty years later, it’s clear to me that The Village is two-thirds of a good-to-great movie, ultimately undone by the unyielding desire to juice up the proceedings with an outlandish twist ending. For that first hour, Shyamalan has done a fine job of dropping us into this outdated community, learning their rules and restrictions, and gradually feeling the dread that the old ways might not protect them from the monsters just along the boundaries. There’s an efficiency and confidence to that first hour, with carefully planned shots that establish key points of information, like little girls panicking at the sight of a red flower and burying it in the ground before going back to their chores. The cinematography is elegant and moody, and the violin-soaring score by James Newton Hoard is a consistent emotive strength. The first encounter with the monsters roaming around the town is fraught with tension, especially as our one character holds out her hand waiting for her friend/love interest to return. The cloaked monsters are also just a cool design, with their long claws and porcupine-like frills extending from their hides.

The greatest strength is Bryce Dallas Howard (Jurassic World) as our surprise protagonist, Ivy, daughter of the community founder, Edward Walker (William Hurt). Howard had made small cameo roles in her father’s films, but she was cast by Shyamalan after he watched her perform on stage. She is spellbinding as Ivy, a woman of great vulnerability and strength, of integrity and charisma. The scene where she sits down on the porch beside Lucius (Joaquin Phoenix) and dance around the edges of flirting is sensational, and when she talks about seeing people’s colors, or auras, and then smirkingly whispers, “No, I will not tell you your color, stop asking,” in the same breath, I defy anyone not to fall in love with her like poor Lucius. This simple love story actually works well. Lucius is an introverted man given to great emotions he doesn’t know how to fully express, which pairs nicely with the chatty and ebullient Ivy. The protagonist shift works wonderfully as well. For the first hour we believe we’re following Lucius as our main character, especially since at this point Phoenix’s star power was rising and Howard had none. Then, with the sudden sticking of a knife, Lucius is taken down and the movie becomes Ivy’s story and her quest to save her beloved. Her cry of not being able to see Lucius’ color is a well-coordinated punch to the gut. This is an example of a rug pull that really works, elevating the stakes and presenting the real star, the girl so many have overlooked for one reason or another, who will be our hero when we need her most.

The greatest strength is Bryce Dallas Howard (Jurassic World) as our surprise protagonist, Ivy, daughter of the community founder, Edward Walker (William Hurt). Howard had made small cameo roles in her father’s films, but she was cast by Shyamalan after he watched her perform on stage. She is spellbinding as Ivy, a woman of great vulnerability and strength, of integrity and charisma. The scene where she sits down on the porch beside Lucius (Joaquin Phoenix) and dance around the edges of flirting is sensational, and when she talks about seeing people’s colors, or auras, and then smirkingly whispers, “No, I will not tell you your color, stop asking,” in the same breath, I defy anyone not to fall in love with her like poor Lucius. This simple love story actually works well. Lucius is an introverted man given to great emotions he doesn’t know how to fully express, which pairs nicely with the chatty and ebullient Ivy. The protagonist shift works wonderfully as well. For the first hour we believe we’re following Lucius as our main character, especially since at this point Phoenix’s star power was rising and Howard had none. Then, with the sudden sticking of a knife, Lucius is taken down and the movie becomes Ivy’s story and her quest to save her beloved. Her cry of not being able to see Lucius’ color is a well-coordinated punch to the gut. This is an example of a rug pull that really works, elevating the stakes and presenting the real star, the girl so many have overlooked for one reason or another, who will be our hero when we need her most.

But then it all falls apart for me once Shyamalan reveals two twists: 1) the monsters are not real, merely costumes the adults wear to enforce their rules through fear, 2) the setting of this village is not 1897 but modern-day, with the villagers living in a secluded nature preserve. Apparently, Edward was able to gather enough violent crime victim relatives to begin this experiment in “returning to our roots.” He served as an American History professor, so who better than to create a thriving community? You know how to establish safe drinking water there, my guy? How about cabin-building? I assume one of the elders must have had some wealth as it’s revealed later, via Shyamalan’s onscreen cameo role, that the government got paid off to stop having airplanes fly over the nature preserve. I actually kind of hate this twist. It feels the most superfluous of all Shyamalan’s fabled twist endings. I was genuinely enjoying the movie and how it was spinning up until this point, but Shyamalan cannot leave well enough alone. I get that Shyamalan is crafting an allegory for the War on Terror and the constant anxiety of post-9/11 America, replete with color codes meant to serve as warning signs. I get that we’re meant to find the town elders as villains, keeping their community repressed through the fear of convenient monsters. The lessons are there to dissect, but I’m disappointed because I was enjoying the allegory on its literal level more than its intended themes. It’s also because I feel like the twists overburden the movie’s charms.

Another reason the twist really falters is that it creates all sorts of nagging questions that sabotage whatever internal logic had been earlier accepted. Adults deciding to break free from modern society so they can start their own secluded LARP community can work as a premise, but it requires a lot more examination that cannot happen when it’s slotted as a concluding twist. Imagine the kind of determination it would take to retreat from modern society and rekindle an agrarian life from hundreds of years ago. That means abandoning all your family, friends, the comforts of modern-day, and the sacrifices could have been explored, but again, it’s just a twist. There are present-day communities, most famously the Amish, that shun the technological advances of modern society to retain an outdated sense of homespun culture and religious community, but often the members have grown up in this culture already. Regardless, retreating into the woods to start your own 18th century cosplay is a commitment, but when you know all the adults are in on this secret, why are they staying in character at all times? When it’s just two adults talking to one another, why are they keeping to their “characters” and talking in that antiquated jargon and syntax? Is it collective Method acting? Is it a sign they’ve ref-ramed what they consider normal? Have they gone so deep that their muscle memory is to say “thee” and “thou” vernacular in the mirror? They went through this elaborate facade because they lost people in the “real world,” but human impulses, violence, and accidents can occur in any community, no matter if you got cell phones or pitchforks. It starts to gnaw away at the tenuous reality of the scenario, a reality I was accepting until the late rug pull.

Another reason the twist really falters is that it creates all sorts of nagging questions that sabotage whatever internal logic had been earlier accepted. Adults deciding to break free from modern society so they can start their own secluded LARP community can work as a premise, but it requires a lot more examination that cannot happen when it’s slotted as a concluding twist. Imagine the kind of determination it would take to retreat from modern society and rekindle an agrarian life from hundreds of years ago. That means abandoning all your family, friends, the comforts of modern-day, and the sacrifices could have been explored, but again, it’s just a twist. There are present-day communities, most famously the Amish, that shun the technological advances of modern society to retain an outdated sense of homespun culture and religious community, but often the members have grown up in this culture already. Regardless, retreating into the woods to start your own 18th century cosplay is a commitment, but when you know all the adults are in on this secret, why are they staying in character at all times? When it’s just two adults talking to one another, why are they keeping to their “characters” and talking in that antiquated jargon and syntax? Is it collective Method acting? Is it a sign they’ve ref-ramed what they consider normal? Have they gone so deep that their muscle memory is to say “thee” and “thou” vernacular in the mirror? They went through this elaborate facade because they lost people in the “real world,” but human impulses, violence, and accidents can occur in any community, no matter if you got cell phones or pitchforks. It starts to gnaw away at the tenuous reality of the scenario, a reality I was accepting until the late rug pull.

It also eliminates some of the stakes of Act Three when Ivy travels beyond the boundaries and may face the wrath of the monsters. It’s maddening that Shyamalan reveals the monsters are not real, mere tools to scare the children into obedience, and then has a supposed suspense sequence where Ivy stumbles upon a thicket of red flowers, the dreaded color the monsters hate. But wait, you might recall, there are no monsters, so then why does it matter? When you realize that her dad could just have taken a hike and driven to a drug store to gather medical supplies, without the supernatural threat keeping them confined, it kind of seems silly. Here you were, worried about the fate of this blind girl, when there’s no reason she had to even venture into this danger because one of the adults could have performed the same task without risking their big secret. I know they think Ivy’s blindness might uphold their secret, but why even risk her possible danger from falling down a hill she couldn’t see or a rock that twists her ankle? Her dad would rather have his blind daughter venture into the woods than do this trek “to the next town” himself. At the same time, her personal journey outside the community is robbed of the supernatural danger and it also re-frames the father as someone burdening his blind daughter with a task he could have achieved. He says she has the power of love and that will guide here, but you know a compass could also help. You could make the argument that maybe his guilt was eating away at upholding such a big secret, maybe he wanted to get caught, but I don’t buy it. Edward argues with his fellow elders that it is the next generation that will keep hold to their traditions and ways of life, and they must ensure this survival. That doesn’t sound like the perspective of a man wishing to break apart the close-knit community he helped build.

What to make of Adrien Brody’s mentally challenged character, Noah? He’s living in a time that doesn’t know how to handle his condition, but he’s also set up as a quasi-villain. He’s the one who stabs Lucius out of jealousy that Ivy favors him. He’s the one who breaks free, steals a monster get-up, and antagonizes Ivy in the woods. He also falls into a pit and dies alone. I don’t really know how to feel about this character because I don’t think Shyamalan exactly knows what to do with him.

What to make of Adrien Brody’s mentally challenged character, Noah? He’s living in a time that doesn’t know how to handle his condition, but he’s also set up as a quasi-villain. He’s the one who stabs Lucius out of jealousy that Ivy favors him. He’s the one who breaks free, steals a monster get-up, and antagonizes Ivy in the woods. He also falls into a pit and dies alone. I don’t really know how to feel about this character because I don’t think Shyamalan exactly knows what to do with him.

Having recently re-read my original 2004 review, I’m amazed that I am sharing almost the exact same response as I did with my younger self. Even some of the critical points have similar wording. My concluding summation still rings true for me: “It’s not that the final twists and revelations are bad; it’s that they paint everything that came before them in a worse light.” You can rightly tell an allegorical story about people rejecting modern society and living a secluded and hidden life. You can rightly tell a story about adults posing as monsters to keep their children in line and obedient. However, if you’re going to be telling me that story, don’t supply an hour’s worth of setup that will be damaged from these revelations. After The Village, it was a steady decline for the filmmaker once dubbed “the next Spielberg” until 2017’s stripped down thriller Split, anchored by a tour de force performance from James McAvoy. It’s frustrating to watch The Village because it has so much good to offer but ultimately feels constrained by the man’s need to follow a formula that had defined him as a mass market storyteller. This was a turning point for Shyamaln’s fortunes, but the quality of The Village has me pleading that he could have shook off the need for ruinous twists and just accepted the potency of what was already working so well.

Re-View Grade: B-

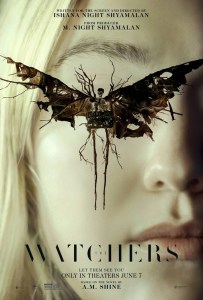

I Saw the TV Glow (2024)/ The Watchers (2024)

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

Nate’s Grade: B

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

Nate’s Grade: C

Knock at the Cabin (2023)

Knock at the Cabin continues M. Night Shyamalan’s more streamlined, single-location focus of late, and while it still has some of his trademark miscues, it’s surprisingly intense throughout and Shyamalan continues improving as a director. The premise, based off the novel by Paul Tremblay, is about four strangers (Dave Bautista, Nikki Amuka-Bird, Rupert Grint, Abby Quinn) knocking on the door of a gay couple’s (Jonathan Groff, Ben Aldridge) cabin. These strangers, which couldn’t be any more different from one another, say they have come with a dire mission to see through. Each of them has a prophetic vision of an apocalypse that can only be avoided if one of the family members within the cabin is chosen to be sacrificed. Given this scenario, you would imagine there is only two ways this can go, either 1) the crazy people are just crazy, or 2) the crazy people are right (if you’ve unfortunately watched the trailers for the movie, this will already have been spoiled for you). I figured with only two real story options, though I guess crazy people can be independently crazy and also wrong, that tension would be minimal. I was pleasantly surprised how fraught with suspense the movie comes across, with Shyamalan really making the most of his limited spaces in consistently visually engaging ways. His writing still has issues. Characters will still talk in flat, declarative statements that feel phony (“disquietude”?), the news footage-as-exposition device opens plenty of plot hole questions, and his instincts to over-explain plot or metaphor are still here though thankfully not as bad as the finale of Old, and yet the movie’s simplicity also allows the sinister thought exercise to always stay in the forefront. Even though it’s Shyamalan’s second career R-rating, there’s little emphasis on gore and the violence is more implied and restrained. I don’t think Shyamalan knows what to do with the extra allowance of an R-rating. The chosen couple, and their adopted daughter, are told that if they do not choose a sacrifice, they will all live but walk the Earth as the only survivors. It’s an intriguing alternative, reminding me a bit of The Rapture, an apocalyptic movie where our protagonist refuses to forgive God and literally sits out of heaven (sill worth watching). The stabs at social commentary are a bit weaker here, struggling to make connections with mass delusions and confirmation bias bubbles. I really thought more was going to be made about one of the couple being a reformed believer himself, with the apocalyptic setup tapping into old religious programming. It’s a bit of an over-extended Twilight Zone episode but I found myself nodding along for most of it, excusing the missteps chiefly because of the power of Bautista. This is a very different kind of role for the man, and he brings a quiet intensity to his performance that is unnerving without going into campy self-parody. He can genuinely be great as an actor, and Knock at the Cabin is the best example yet of the man’s range. For me, it’s a ramshackle moral quandary thriller that overcomes Shyamalan’s bad writing impulses and made me actually feel some earned emotion by the end, which is more than I was expecting for an apocalyptic thriller under 100 minutes. What a twist.

Knock at the Cabin continues M. Night Shyamalan’s more streamlined, single-location focus of late, and while it still has some of his trademark miscues, it’s surprisingly intense throughout and Shyamalan continues improving as a director. The premise, based off the novel by Paul Tremblay, is about four strangers (Dave Bautista, Nikki Amuka-Bird, Rupert Grint, Abby Quinn) knocking on the door of a gay couple’s (Jonathan Groff, Ben Aldridge) cabin. These strangers, which couldn’t be any more different from one another, say they have come with a dire mission to see through. Each of them has a prophetic vision of an apocalypse that can only be avoided if one of the family members within the cabin is chosen to be sacrificed. Given this scenario, you would imagine there is only two ways this can go, either 1) the crazy people are just crazy, or 2) the crazy people are right (if you’ve unfortunately watched the trailers for the movie, this will already have been spoiled for you). I figured with only two real story options, though I guess crazy people can be independently crazy and also wrong, that tension would be minimal. I was pleasantly surprised how fraught with suspense the movie comes across, with Shyamalan really making the most of his limited spaces in consistently visually engaging ways. His writing still has issues. Characters will still talk in flat, declarative statements that feel phony (“disquietude”?), the news footage-as-exposition device opens plenty of plot hole questions, and his instincts to over-explain plot or metaphor are still here though thankfully not as bad as the finale of Old, and yet the movie’s simplicity also allows the sinister thought exercise to always stay in the forefront. Even though it’s Shyamalan’s second career R-rating, there’s little emphasis on gore and the violence is more implied and restrained. I don’t think Shyamalan knows what to do with the extra allowance of an R-rating. The chosen couple, and their adopted daughter, are told that if they do not choose a sacrifice, they will all live but walk the Earth as the only survivors. It’s an intriguing alternative, reminding me a bit of The Rapture, an apocalyptic movie where our protagonist refuses to forgive God and literally sits out of heaven (sill worth watching). The stabs at social commentary are a bit weaker here, struggling to make connections with mass delusions and confirmation bias bubbles. I really thought more was going to be made about one of the couple being a reformed believer himself, with the apocalyptic setup tapping into old religious programming. It’s a bit of an over-extended Twilight Zone episode but I found myself nodding along for most of it, excusing the missteps chiefly because of the power of Bautista. This is a very different kind of role for the man, and he brings a quiet intensity to his performance that is unnerving without going into campy self-parody. He can genuinely be great as an actor, and Knock at the Cabin is the best example yet of the man’s range. For me, it’s a ramshackle moral quandary thriller that overcomes Shyamalan’s bad writing impulses and made me actually feel some earned emotion by the end, which is more than I was expecting for an apocalyptic thriller under 100 minutes. What a twist.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Old (2021)

Old, M. Night Shyamalan’s latest thriller, seems ripe for parody, perhaps even upon delivery in theaters. The “can’t even” bizarre energy of this movie is off the charts and bounces back and forth between hilarious camp and head-scratching seriousness with several frustrating and absurd artistic decisions by Shyamalan. If you viewed this movie as a strange comedy, then you would be right. If you viewed it as an existential horror movie, then you would be right. If you viewed it as a heightened satire on high-concept Twilight Zone parables, then you would be right.

We follow a family on a vacation to a Caribbean resort. Guy (Gael Garcia Bernal) and Prisca (Vicky Krieps) are keeping secrets from their two children, six-year-old Trent (Nolan River) and eleven-year-old Maddox (Alexa Swinton). The parents are planning on separating and Prisca has a tumor, though benign for the time being. The hotel manager offers an exclusive secluded beach for those who would really enjoy this special experience. Guy, Prisca, and their kids join another family with a six-year-old daughter, a married couple, and an old lady with her dog, and they drive off into the jungle. Except this beach is not what it appears to be. There are strange artifacts of past visitors, and every time people try and pass back through the path to leave, they pass out. Also, everyone is aging rapidly, about one year for every 30 minutes elapsed. The children become adults, the elderly succumb first, and everyone worries they may not ever leave.

Old is not one of Shyamalan’s worst movies but it’s hard to classify it as good without attaching conditional modifiers. It might be good, if you enjoy movies that are campy and schlocky. It might be good, if you enjoy movies that throw anything and everything out there just because. It might be good, if you enjoy movies that produce a supernatural concept, drop rules established whenever convenient, and then try to wrap everything up neatly with an absurdly thorough explanation for everything. It might be good, if you think Shyamalan peaked with 2006’s Lady in the Water. This is going to be a polarizing experience. I think Shyamalan doesn’t fully understand what tone he’s going for and how best to develop his crazy storyline in a way that makes it meaningful beyond the general WTF curiosity. Even when it goes off the rails, Old is entertaining but some of that is unintentional. There are points where it feels like Shyamalan is trying for camp and other points where it feels like he is aiming for something higher and just can’t help but stumble, Sisyphean-style, back again into the pit of camp absurdity.

The premise is a grabber and takes the contained thriller conceit that Hollywood loves for its cheap cost and applies a supernatural sheen. It’s based upon a French graphic novel, Sandcastle by Pierre-Oscar Levy and Frederik Peeters, though Shyamalan has taken several creative liberties. It’s an intriguing idea of rapid aging being the real trap, and it forces many characters to confront their own fears of mortality and aging but also parental failures. Every parent likely thinks with some degree of regret about how quickly their little ones grow up. These adults have to watch their children rapidly age in only hours and not have any way to stop the relentless speed of time. The extra level of fear is produced by the fact that mentally the children are still where they began that morning. Even as Trent ages into the body of a teenager, he still has the mind of a six-year-old, and that is a horror unto itself. As his body rapidly changes, his parents are helpless to stop this terrifying jolt into adulthood and unable to shield their child from the terror of physical maturation but being trapped in the mindset of a child who cannot keep up with their mutating body. There are definite body horror and existential dread potential here, though Shyamalan veers too often into lesser schlocky thriller territory. For him, it’s more the mystery or the foiled escape attempts than actually dwelling on the emotional anxiety of the unique predicament. There’s enough born from this premise that it keeps you watching to the end, even as you might be questioning the actions of the characters, their ability to somehow miraculously guess the right answers as a group about what is happening, and the inconsistency of the rules about what can and cannot happen on this accursed beach.

There is one sequence that deserves its own detailed analysis for just how truly bizarre and avoidable it could have been, and to do so I will need to invoke the warning of spoilers for this paragraph. One of the other six-year-olds, Kara, gets a whole traumatic experience all her own that is morally and artistically questionable. Midway through the movie, Kara (Eliza Scanlan) and Trent (Alex Wolff) come back from a jaunt off screen together and they’re older and Kara is clearly pregnant. Given the rules that were established, that means that these six-year-old children experimented with their newly adult bodies to the point of fertilization (oh God, writing this makes me wince). I must reiterate that these characters are still six-years-old. Before you start realizing the gross implications, Kara is quickly entering labor and within seconds the baby is suddenly born and within seconds the baby just as suddenly dies silently from, what we’re told, was a lack of attention. What he hell, Shyamalan? Did you have to throw a dead baby into your movie to make us feel the visceral horror of the situation? It feels tacky and needlessly triggering for some moviegoers. This entire sequence doesn’t impact the plot in any meaningful way. Kara could have died in childbirth because of the circumstances of the beach. That would be tragic but matter. Just having her get suddenly pregnant and then suddenly the recipient of a deceased child seems needlessly cruel and misguided. And then, in the aftereffect of this trauma, Kara’s mom tearfully recounts her first love, a man she still thinks about to this day but doesn’t understand why. What does this have to do with anything? Re-read this entire scenario and let it sink in how truly uncomfortable and gross it comes across. It could have been avoided, it could have even been better applied to the characters and themes of the story, but it’s empty, callous shock value.

Another hindrance of Old is that the characters lack significant development and nobody ever talks like a recognizable human being. As Shyamalan has embraced being more and more an unabashedly genre filmmaker, he’s lost sight on how to write realistic people. You see this throughout 2008’s The Happening with its curious line readings and clunky, inauthentic dialogue being legendary and unintentionally hilarious (“You should be more interested in science, Jake. You know why? Because your face is perfect.”). I feel like Old is the most reminiscent of The Happening, the last time Shyamalan went for broke with ecological horror. The way these characters talk, it sounds like their dialogue was generated by an A.I. instead. “You have a beautiful voice. I can’t wait to hear it when you’re older,” Prisca says, which is a strange way for a parent to say, “I like what you have but wishing it was better.” She also has the line to her husband, “When you talk about the future, I don’t feel seen.” There’s also a running theme of characters just blurting out their occupations as introductions, “I’m a doctor,” followed by, “I’m a nurse,” like it’s career day on the beach. Frustratingly, all the characterization ends once the people wind up on this fated beach. Many of these characters are simply defined by their maladies and professions. This character has seizures. This character has a blood disorder. This character has a tumor. This character has MS. Noticing a pattern? You would expect that with such a unique and challenging conflict that it would better reveal these people, push them to make changes, especially as change is thrust upon them whether they like it or not. Imagine your uncle being cursed with rapid aging but all he does is still complain about his lousy neighbor. That limited tunnel vision is what Old struggles with. And one of the characters is a famous rapper named Mid-Sized Sedan but without a hint or irony or showbiz satire. Mid-Sized Sedan!

The way Shyamalan shoots this movie also greatly increases its camp appeal. This movie is coursing with energy and contrarianism. Shyamalan is often moving his camera in swooping pans and finding visual arrangements that can be frustrating and obtuse. Sometimes it works, like when we have the child characters with their backs to the camera and we’re anticipating how they have changed and what they might look like. Too often, it feels like Shyamalan trying to interject something more into a scene like he’s unsure that the dramatic tension of the writing is enough. There are scenes where what’s important almost seems incidental to the visual arrangement of the shot. Some of the sudden push-ins and arrangements made me laugh because it took me out of the moment by making the moment feel even more ridiculous. This heightened mood to the point of hilarity is the essence of camp and that’s why it feels like Shyamalan can’t help himself. If he’s trying to dig for something deeper and more profound, it’s not happening with his exaggerated and mannered stylistic choices being a distraction.

The ending, which I will not spoil, tries to do too much in clearing up the central mysteries. It feels overburdened to the point of self-parody, having characters pout expository explanations for all that came before and supplying motivation as to what was happening. Still, Shyamalan cannot keep things alone, and he keeps extending his conclusion with more and more false endings to complicate matters; the more he attempts to tidy up the less interesting the movie becomes. I would have been happy to accept no explanation whatsoever for why the beach behaves as it does. The best Twilight Zone episodes succeed from the mystery and development rather than the eventual explanation (“Oh, it was all a social experiment/nightmare/whatever”). Once you begin to pick apart the explanation with pesky questions, the illusion of its believability melts away. I had the same issue with 2019’s Us. The more Jordan Peele tried to find a way to explain his underground doppelganger plot, the more incredulous and sillier it became.

Old is a Shyamalan movie for all good and bad. It’s got a strong central premise and some memorable moments but those memorable moments are also both good and bad. Some of the moments have to be seen to be believed, and some of those moments are simply the odd choices that Shyamalan makes as a filmmaker as well as a screenwriter. It’s hard to say whether the movie’s weirdness will be appealing or revolting to the individual viewer. It feels like camp without intentionally going for camp. Rather, Shyamalan seems to be going for B-movie schlock whereas his older movies took B-movie premises and attempted to elevate them with themes, well-rounded characters, and moving conclusions (don’t forget the requisite twist endings). The worst sin a movie can commit is being boring, and Old is rarely that. I can’t say it’s good for the entire duration of its overextended 100 minutes but it does not prove boring.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Glass (2019)

M. Night Shyamalan has had a wildly fluctuating career, but after 2017’s killer hit Split he’s officially back on the upswing and the Shyamalan bandwagon is ready for more transplants. At the very end of Split it was revealed it had secretly existed in the same universe as Unbreakable, Shyamalan’s so-so 2000 movie about real-life superheroes. Fans of the original got excited and Shyamalan stated his next film was a direct sequel. Glass is the long-anticipated follow-up and many critics have met it with a chilly response. Shyamalan’s comeback is still cruising, and while Glass might not be as audacious and creepy clever as Split it’s still entertaining throughout its two-hour-plus run time.

M. Night Shyamalan has had a wildly fluctuating career, but after 2017’s killer hit Split he’s officially back on the upswing and the Shyamalan bandwagon is ready for more transplants. At the very end of Split it was revealed it had secretly existed in the same universe as Unbreakable, Shyamalan’s so-so 2000 movie about real-life superheroes. Fans of the original got excited and Shyamalan stated his next film was a direct sequel. Glass is the long-anticipated follow-up and many critics have met it with a chilly response. Shyamalan’s comeback is still cruising, and while Glass might not be as audacious and creepy clever as Split it’s still entertaining throughout its two-hour-plus run time.

It’s been 18 years since David Dunn (Bruce Willis) discovered his special abilities thanks to the brilliant but criminally insane Elijah Price (Samuel L. Jackson), a.k.a. “Mr. Glass.” David has been going on “walks” from his security day job to right wrongs as “The Overseer,” the rain slicker-wearing man who is incapable of being harmed (exception: water). He looks to stop David Wendell Crumb (James McAvoy), a.k.a. The Horde, a disturbed man inhabited by over dozens of personalities. David Dunn and Kevin are captured and placed in the same mental health facility as Elijah. The three are under the care of Dr. Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson) who specializes in a specific form of mental illness with those who believe to be superheroes. She has only so many days to break through to these dangerous men or else more extreme and irrevocable measures might be taken.

Shyamalan has a lot on his mind and spends much of the second half exploring the classical ideas of superheroes via Dr. Staple and her unorthodox therapy treatments. She’s trying to convince each man they are simply wounded individuals and not superior beings blessed with superior powers. Because the audience already knows the fantastic truth, I’m glad Shyamalan doesn’t belabor this angle and make the crux of the movie about her convincing them otherwise. The second act is something of a sleeping predator, much like the wheelchair-bound, brittle-bone Elijah Price. You’re waiting for the larger scheme to take shape and the snap of the surprise, and Shyamalan throws out plenty of red herrings to keep you guessing (I’ve never been more glad that convenient news footage of a new skyscraper opening meant absolutely nothing for the final act setting). Part of the enjoyment is watching the characters interact together and play off one another. The conversations are engaging and the actors are uniformly good, so even these “slow parts” are interesting to watch.

Shyamalan has a lot on his mind and spends much of the second half exploring the classical ideas of superheroes via Dr. Staple and her unorthodox therapy treatments. She’s trying to convince each man they are simply wounded individuals and not superior beings blessed with superior powers. Because the audience already knows the fantastic truth, I’m glad Shyamalan doesn’t belabor this angle and make the crux of the movie about her convincing them otherwise. The second act is something of a sleeping predator, much like the wheelchair-bound, brittle-bone Elijah Price. You’re waiting for the larger scheme to take shape and the snap of the surprise, and Shyamalan throws out plenty of red herrings to keep you guessing (I’ve never been more glad that convenient news footage of a new skyscraper opening meant absolutely nothing for the final act setting). Part of the enjoyment is watching the characters interact together and play off one another. The conversations are engaging and the actors are uniformly good, so even these “slow parts” are interesting to watch.

It’s fun to watch both Willis and Jackson to slip right into these old characters and conflicts, but it’s really McAvoy’s movie once more, to our immense benefit. Between a ho-hum character who has accepted his ho-hum city guardian role, and an intellectual elite playing possum, the narrative needs Kevin Wendell Crumb/The Horde to do its heavy lifting. McAvoy is phenomenal again and seamlessly transitions from one personality to another, aided by Dr. Staple’s magic personality-switching light machine. The command that McAvoy has and range he establishes for each character is impressive. He reserves different postures, different expressions, and different muscles for the different personas. I was genuinely surprised how significant Ana Taylor-Joy (Thoroughbreds) was as the returning character Casey, the heroine that escaped Kevin’s imprisonment in Split. She’s concerned for the well being of Kevin, the original personality who splintered into many as a means of protection from his mother’s horrifying abuse. I was worried the movie was setting her up to be a disciple of Kevin’s, looking to break him out having fallen under an extreme Stockholm syndrome. This is not the case. She actually has a character arc about healing that is important and the thing to save Kevin’s soul. There are in-Kevin personalities here with more character arcs than the other famous leads.

Shyamalan has been improving in his craft as a director with each movie, and stripping down to the basics for a contained thriller gave him a better feel for atmospherics and visual spacing with his frame. With Glass, the cinematography by Mike Gioulakis (It Follows, Us) smartly and elegantly uses color to help code the characters and the development of their psychological processes. The direction by Shyamalan feels a bit like he’s looking back for a sense of visual continuity from his long takes and pans from Unbreakable, which places greater importance on the performances and precise framing.

I think the disappointment expressed in many of the mixed-to-negative critical reviews comes down to a departure in tone as well as the capitalization of being an Unbreakable sequel. Both of the previous movies in this trilogy were less action vehicles than psychological thrillers that emphasized darker human emotions and personal struggle. Shyamalan purposely grounded them, as much as one can, in a sense of vulnerable realism, which only made both of their endings stick out a little more. The movies weren’t about existing in a superhero universe but more so about unknown heroes and villains of comic-sized scale living amongst us every day. It was about the real world populated with super beings. Because of that tonal approach, Unbreakable was the epic tale of a security guard taking down one murderous home invader and surviving drowning. It was more the acceptance of the call, and part of that was getting an audience that had not been fed as much superhero mythos as today to also accept that secret reality hiding in plain sight. 18 years later, movie audiences have become highly accustomed to superheroes, their origins, and the tropes of the industry, so I was looking forward to Shyamalan’s stamp. I think our new cultural environment gave Shyamalan the room to expand, and Glass moves into a less realistic depiction of these elements. It’s not the gritty, understated, and more psychologically drawn dramas of his past. It’s more comfortable with larger, possibly sillier elements and shrugging along with them. There are moments where characters will just flat-out name the tropes happening on screen, with straight-laced exposition. It can lead to some chuckles. I think fans of the original might find a disconnect in tone between the three films, especially with this capper. They might ask themselves, “I waited 18 years for these characters to just become like other supers?”

I think the disappointment expressed in many of the mixed-to-negative critical reviews comes down to a departure in tone as well as the capitalization of being an Unbreakable sequel. Both of the previous movies in this trilogy were less action vehicles than psychological thrillers that emphasized darker human emotions and personal struggle. Shyamalan purposely grounded them, as much as one can, in a sense of vulnerable realism, which only made both of their endings stick out a little more. The movies weren’t about existing in a superhero universe but more so about unknown heroes and villains of comic-sized scale living amongst us every day. It was about the real world populated with super beings. Because of that tonal approach, Unbreakable was the epic tale of a security guard taking down one murderous home invader and surviving drowning. It was more the acceptance of the call, and part of that was getting an audience that had not been fed as much superhero mythos as today to also accept that secret reality hiding in plain sight. 18 years later, movie audiences have become highly accustomed to superheroes, their origins, and the tropes of the industry, so I was looking forward to Shyamalan’s stamp. I think our new cultural environment gave Shyamalan the room to expand, and Glass moves into a less realistic depiction of these elements. It’s not the gritty, understated, and more psychologically drawn dramas of his past. It’s more comfortable with larger, possibly sillier elements and shrugging along with them. There are moments where characters will just flat-out name the tropes happening on screen, with straight-laced exposition. It can lead to some chuckles. I think fans of the original might find a disconnect in tone between the three films, especially with this capper. They might ask themselves, “I waited 18 years for these characters to just become like other supers?”

And that refrain might be common as well, namely, “I waited 18 years for this?” While it’s inherently true that a filmmaker doesn’t owe fans anything beyond honest effort, an extended time between sequels does create the buildup of anticipation and the question of whether the final product was worth that excited expectation. Fans of Unbreakable might be somewhat disappointed by the fact that Glass feels like more of a sequel to Split. McAvoy is top-billed for a reason. Perhaps Shyamalan had more of a desire to foster the continuation from a recent hit than an 18-year-old movie. Whatever the rationale, David Dunn gets short shrift. After the opening segment, he’s being institutionalized but he’s not actively trying to escape. As a result, the attention focuses far more onto our two villains, and one of them doesn’t says a word until an hour into the movie. This further exacerbates the disproportionate emphasis on Kevin Wendell Crumb (and The Horde). As stated above, I think that’s where the emphasis should be because he has the most storytelling potential, and McAvoy is amazing. However, if you’ve been waiting 18 years for another face-off between Mr. Glass and the Unbreakable Man, then this might not seem like the special event you dreamt about. Shyamalan still has difficulty staging action sequences. The fights with David and The Beast are pretty lackluster and involve the same non-responsive choke hold moves. There are like half a dozen characters involved with the climactic showdown but half of them are bystanders waiting to be tapped in when the narrative needs them to console their fighter.

I think the ending will also turn some people off for what it does and what it doesn’t do (I’ll avoid spoilers but will be speaking in vague terms this paragraph, so be warned, dear reader). The ending opens up a larger world that leaves you wanting more, even if it was only a passing scene acknowledging the resolution to the final actions. This holds true with an organization that you get only the smallest exposure to that adds to the deluge of questions seeking answers. It sets up a bigger picture with bigger possibilities that will ultimately be left unattended, especially if Shyamalan’s recent interviews are to be taken at face value. What Glass does not do is play with the implications of its ending and explore the newer developments. The ending we do get is indeed ballsy. I gasped. Shyamalan takes some big chances with the direction he chooses to take his story, and I can admire his vision and sense of closure. On the other end, I know that these same decisions will likely inflame the same contingent of disgruntled and disappointed fans.

I think the ending will also turn some people off for what it does and what it doesn’t do (I’ll avoid spoilers but will be speaking in vague terms this paragraph, so be warned, dear reader). The ending opens up a larger world that leaves you wanting more, even if it was only a passing scene acknowledging the resolution to the final actions. This holds true with an organization that you get only the smallest exposure to that adds to the deluge of questions seeking answers. It sets up a bigger picture with bigger possibilities that will ultimately be left unattended, especially if Shyamalan’s recent interviews are to be taken at face value. What Glass does not do is play with the implications of its ending and explore the newer developments. The ending we do get is indeed ballsy. I gasped. Shyamalan takes some big chances with the direction he chooses to take his story, and I can admire his vision and sense of closure. On the other end, I know that these same decisions will likely inflame the same contingent of disgruntled and disappointed fans.

Shyamalan’s third (and final?) film in his Unbreakable universe places the wider emphasis on the three main characters and their interactions. While McAvoy and Kevin get the light of the spotlight, there are strong moments with Elijah and David Dunn. There are some nifty twists and turns that do not feel cheap or easily telegraphed, which was also a Shyamalan staple of his past. It’s not nearly as good or unnerving as Split, the apex of the Shyamalanaissance, but it entertains by different means. If you were a fan of Unbreakable, you may like Glass, but if you were a fan of Split, I think you’ll be more likely to enjoy Glass. It might not have been worth 18 years but it’s worth two hours.

Nate’s Grade: B

Split (2017)

It’s hard to even remember a time when writer/director M. Night Shyamalan wasn’t a cinematic punching bag. He flashed onto the scene with the triumviri of Sixth Sense, Unbreakabale, and Signs, what I’ll call the Early Period Shyamalan. He was deemed the next Spielberg, the next Hitchcock, and the Next Big Thing. Then he entered what I’ll call the Middle Period Shyamalan and it was one creative and commercial catastrophe after another. The Village. Oof. Lady in the Water. Ouch. The Happening. Yeesh. The Last Airbender. Ick. After Earth. Sigh. That’s a rogue’s gallery of stinkers that would bury most directors. The promise of his early works seemed snuffed out and retrospectives wondered if the man was really as talented as the hype had once so fervently suggested. Then in 2015 he wrote and directed a small found footage thriller called The Visit and it was a surprise hit. Had the downward spiral been corrected? With a low-budget and simple concept, had Shyamalan staked out a course correction for a mid-career resurgence. More evidence was needed. Split is the confirmation movie fans have been hoping for. An M. Night Shyamalan movie is no longer something to fear (for the wrong reasons), folks.

It’s hard to even remember a time when writer/director M. Night Shyamalan wasn’t a cinematic punching bag. He flashed onto the scene with the triumviri of Sixth Sense, Unbreakabale, and Signs, what I’ll call the Early Period Shyamalan. He was deemed the next Spielberg, the next Hitchcock, and the Next Big Thing. Then he entered what I’ll call the Middle Period Shyamalan and it was one creative and commercial catastrophe after another. The Village. Oof. Lady in the Water. Ouch. The Happening. Yeesh. The Last Airbender. Ick. After Earth. Sigh. That’s a rogue’s gallery of stinkers that would bury most directors. The promise of his early works seemed snuffed out and retrospectives wondered if the man was really as talented as the hype had once so fervently suggested. Then in 2015 he wrote and directed a small found footage thriller called The Visit and it was a surprise hit. Had the downward spiral been corrected? With a low-budget and simple concept, had Shyamalan staked out a course correction for a mid-career resurgence. More evidence was needed. Split is the confirmation movie fans have been hoping for. An M. Night Shyamalan movie is no longer something to fear (for the wrong reasons), folks.

Split is all about Kevin (James McAvoy), a man living with twenty-three different personalities in his head. One of them, Dennis, kidnaps three young ladies, two popular and well-adjusted friends (Haley Lu Richardson, Jessica Sula) and the introverted, troubled teen, Cassie (Anna Taylor-Joy). The girls wake up locked in a basement and with no idea where they are and whom they’re dealing with. Kevin takes on several different personas: Barry, a fashion designer, Hedwig, an impish child, Patricia, a steely woman devoted to order, Dennis, an imposing threat undone by germs. The altered personalities, or “alters” as they’re called, are preparing for the arrival of a new persona, one they refer to as simply The Beast. And sacrifices are needed for his coming.

Right away you sense that Split is already an above average thriller. This is clever entertainment, a fine and fun return to form for a man that seemed to lose his sense of amusement with film. The areas where Split is able to shine that would have normally doomed the Middle Period Shyamalan are in the realms of tone, execution, and ambition.

Very early on, Shyamalan establishes what kind of feeling he wishes to imbue with his audience, and he keeps skillfully churning those sensations, adding new elements without necessary breaking away from the overall intended experience. You’re meant to be afraid but not too afraid. It’s more thriller than outright horror. There is a level of camp inherent into the ridiculous premise and in watching a grown man act out a slew of wildly different personas populating his brain. Shyamalan swerves into this rather than try and take great pains to make his thriller a more serious, high-minded affair. His camera lingers on the oddities, allowing the audience to nervously laugh, and he allows McAvoy extra time to sell those oddities. It’s especially evident in the introduction of the Patricia alter ego, where McAvoy uses a lot of faux grave facial expressions to great comic effect. Shyamalan no longer seems to fear being seen as a bit silly. Shyamalan even knows in some ways that he’s making a genre picture and an audience expects genre elements or the reversal of those elements. At one point, Dennis insists that two of our girls strip to their underwear because they’re dirty. I shook my head a bit, believing Shyamalan to sneak in some PG-13 T&A. Except it’s just enough for some trailer clips. Shyamalan’s camera doesn’t objectify the teen girls even after they run around in their skivvies. He doesn’t have to indulge genre elements that will break the film’s tone. He also doesn’t have to overly commit to being serious. He can be serious enough, which is the best way to describe Split. It treats its premise and the danger the girls are in with great seriousness, but the movie still allows measures of fun and intended camp. The cosmos themselves don’t have to be responsible for all of time’s events to click together to form his climax. It can just be a young woman trying to escape a psycho thanks to her wits and her grit.

Very early on, Shyamalan establishes what kind of feeling he wishes to imbue with his audience, and he keeps skillfully churning those sensations, adding new elements without necessary breaking away from the overall intended experience. You’re meant to be afraid but not too afraid. It’s more thriller than outright horror. There is a level of camp inherent into the ridiculous premise and in watching a grown man act out a slew of wildly different personas populating his brain. Shyamalan swerves into this rather than try and take great pains to make his thriller a more serious, high-minded affair. His camera lingers on the oddities, allowing the audience to nervously laugh, and he allows McAvoy extra time to sell those oddities. It’s especially evident in the introduction of the Patricia alter ego, where McAvoy uses a lot of faux grave facial expressions to great comic effect. Shyamalan no longer seems to fear being seen as a bit silly. Shyamalan even knows in some ways that he’s making a genre picture and an audience expects genre elements or the reversal of those elements. At one point, Dennis insists that two of our girls strip to their underwear because they’re dirty. I shook my head a bit, believing Shyamalan to sneak in some PG-13 T&A. Except it’s just enough for some trailer clips. Shyamalan’s camera doesn’t objectify the teen girls even after they run around in their skivvies. He doesn’t have to indulge genre elements that will break the film’s tone. He also doesn’t have to overly commit to being serious. He can be serious enough, which is the best way to describe Split. It treats its premise and the danger the girls are in with great seriousness, but the movie still allows measures of fun and intended camp. The cosmos themselves don’t have to be responsible for all of time’s events to click together to form his climax. It can just be a young woman trying to escape a psycho thanks to her wits and her grit.

Execution has also been a nagging problem of the Middle Period Shyamalan (affectionately his Blue Period?). I may be one of the few people that thought 2008’s Happening had some potential even as is if another director with a better feel for the material and less timidity embracing the full possibilities of an R-rating had been aboard. With Last Airbender and After Earth, both movies were exceptionally bad from a number of standpoints, but Shyamalan’s botched execution of them made the anguish all the more realized. You walked away from both disasters and openly wondered why Shyamalan was given such large-scale creative freedom and at what point the producers knew they were sunk. With Split, Shyamalan has pared down his story into a very lean and mean survival thriller anchored by a mesmerizing performance from McAvoy. The story engine kicks in very early, mere minutes into the movie. The man doesn’t even wait the usual ten minutes or so before introducing the inciting incident. This Shyamalan has no time to dawdle, and the rest of the movie lives up to this pacing edict. It’s efficiently plotted with the girls in a position of discovery and learning their surroundings, the different alters, and how to play them against one another. Each piece of info builds upon the last. It’s a survival thriller where you think along with the characters, and their decisions make sense within the internal logic and story that Shyamalan commands. There are scattered interruptions from our subterranean terror, mainly exposition from Kevin’s shrink and some hunting flashbacks from Casey’s childhood with her father. I figured they would show Casey to be similar to the feisty heroine from You’re Next, revealing her as a fiendishly clever and capable survivalist that the villain underestimates to his great peril. It’s not quite that but the flashbacks do serve a purpose, a very dark purpose, and a purpose that could lead to some very uncomfortable personal implications others may interpret.