Blog Archives

Weapons (2025)

Zack Cregger began his career as one of the co-creators and co-stars of the sketch comedy troupe, The Whitest Kids U Know. This led to a poorly received sex comedy, 2009’s Miss March, which Cregger co-directed and starred as the lead. Then in 2022, Cregger made a name for himself in a very different genre, writing and directing Barbarian, a movie whose identity kept shifting with twists and world-building buried underneath its simple Air B&B gone awry setup. From there, Cregger joined the ranks of Jordan Peele, John Krasinski, and other horror-thriller upstarts best known for comedy. It became a question over what Cregger would do next, which sparked a bidding war for Weapons. It’s easy to see why with such a terrific premise: one day a classroom of kids all run out into the night at the same time, all except for one child, and nobody knows why. Weapons confirms Cregger’s genre transformation and the excitement that deservingly follows each new release. Each new Cregger horror movie is a game of shifting expectations and puzzles, though the game itself might be the only point.

The premise is immediately grabbing and Cregger’s clever structural gambits add to that intrigue. Right away in the opening narration from an unseen child, we’re given the state of events in this small town, already reckoning with an unknowable tragedy. The screenplay takes a page from Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino, following different lead characters to learn about their personal perspectives. It continually allows the movie to re-frame itself, allowing us to pick up details or further context with each new person giving us a fuller sense of the big picture. Rather than resetting every twenty minutes or so, the movie offers an implicit promise of delivering something new at those junctures, usually leaving that previous lead character in some kind of dire cliffhanger. With each new portion, we can gain some further insight, but it also allows the story to ground its focus and try on different tones. With Justine (Julia Garner), we see a woman who is trying to figure out how to regain her life she feels has been unfairly stripped away, and many of her coping mechanisms are self-destructive old habits. With Archer (Josh Brolin), we see a father consumed by his sudden loss and the reflection it forces him into, while also obsessing over what possible investigative details he can put together to possibly provide a framework of an answer. Then with other characters, which I won’t spoil, we gain other perspectives less directly involved that approach a dark comedy of errors. At one point, you may even wonder when the movie is going to remember those missing kids again. I appreciated that Cregger resolves his mystery with enough time to really examine its implications. This isn’t just a last-minute twist or Scream-like unveiling of the villain coming to light. I also appreciated that it ends in such an enthusiastic climax that left me cackling and cheering. It’s a mystery with a relatively satisfying answer but a climax that is also cathartic and exhale-inducing after all the dread and build-up.

The technical elements are just as polished as its knotty screenplay. The movie is genuinely unnerving at many points. Even the image of kids Narutu-running off into the night is inherently creepy. There are a few cheap jump scares but most of the movie is built around a quiet sense of desperation and dread. Cregger prefers holding onto shots to build tension, like a door opening and waiting for something, anything to pop out of the darkness. There are moments that made me wince and moments that made me gasp, like suddenly being compelled to stab one’s face with a fork dozens of times. However, a significant drawback for me was the lighting levels of the cinematography. To be clear, the photography was eerie and very evocative. My problem is that this was a movie whose light levels were so low it made it excruciatingly hard to simply identify what was happening onscreen. I’m sure my theater’s dim projection was part of this, but this is also a trend with modern movie-making, the murky lighting, like everyone is trying to recreate those Barry Lyndon’s candle-lit tableaus. Sometimes I just want to see what’s happening in my movie.

Weapons is certainly a thought-provoking premise, but with some distance from the movie, I’m starting to wonder what more there may be under the surface. Now not every movie has to be designed for maximum layers and themes and metaphors; movies can have their own points of appeal before getting to subtext. I do think most viewers will find Weapons engaging and intriguing, and the slippery structure helps make the movie feel new every twenty minutes while also testing out different tones that might have been too obtrusive with different characters and their specific perspectives. However, once you straighten out that timeline and see things clearly, it begs the question what exactly Cregger is actually saying. The sudden and disturbing horror of a classroom of children all disappearing has to have obvious connections to school shootings and mass killings, right? The trauma image is too potent and specifically tied to schools to be accidental or casual. Taking that, what is the movie saying about our culture where one day, any day, a class full of young children can just go missing? Despite a literal floating assault rifle appearing in a dream, there doesn’t appear to be much on the movie’s mind about gun violence or even weapons in general. I’m reminded of my favorite movie of 2020, the criminally under-seen Spontaneous, which explored a world where one high school class of students lived under the threat that at any time they could explode. There was no explanation for this strange phenomenon, though scientists certainly tried, and the focus was instead on the unfair dread hanging over their day-to-day existence, that at any moment their life could be forfeited. The parallel was obvious and richly explored about the pressure and anxieties of a life where this very disturbing reality is considered your accepted new normal. That was a movie with ideas and messages linking them to its school-setting of metaphorical trauma. I can’t say the same with Weapons.

I’ve read some people analyze each one of the characters as one of the stages of alcoholism, and I’ve read other people argue that the movie is an exploration of a town come undone through unexplainable trauma, but I seriously doubt that last one. Don’t you think the mystery of the missing class would draw national and international media attention? Hangers-ons thinking they cracked the case? Intruders harassing the bigger names? People trying to exploit a tragedy for money or a sense of self-importance? Conspiracy theorists linking this mystery to their other data points for a larger conspiracy? It doesn’t feel like the impact of this unique mystery has escaped the county lines. Certainly there are characters searching for answers and treating this poor schoolteacher as a scapegoat for their collective fears and anger, but by turning the screenplay into a relay race where one character hands off to the next for time in the spotlight, it doesn’t expand our sense of the town and the broader effects of this bizarre tragedy. Instead, it pens in the characters we do have, which all seem to interact with those very same characters, making the bigger world feel actually smaller. Narrowing the lens of perspectives makes it more difficult to articulate commentary about community breakdown in the face of uncertainty. The creative choices square with the central mystery and the nesting-doll structure, playing a game with the audience to discover the source of this incident, but once you discover that source, and once we reach our ending, you too may appreciate Cregger’s narrative sleight-of-hand but eventually wonder, “Is that all there is?” Maybe so.

Weapons is an effective and engaging follow-up for Cregger and confirms that whatever stories he feels compelled to tell in horror are worthy of watching, preferably with as little prior information as possible. You definitely feel you’re in the confidant hands of a natural storyteller who enjoys throwing out surprises and shock value. I have some grumbles about ultimately what might all be behind that intriguing mystery and the lack of foundational commentary that would permit multiple viewings of close analysis. Then again not every movie is meant to be a repeat viewing. Some movies are one-and-dones but still enjoyable, and that might best sum up Weapons. It’s sharp and cleverly designed but maybe lacking a finer point.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Fantastic Four: First Steps (2025)

Apparently there must have been an ancient curse that brings forth a new attempt at a Fantastic Four franchise every ten years, even further if you want to include the 1994 Roger Corman movie that was purposely made and never released just to hold onto the film rights (I’ve seen it, and once you forgive the chintzy special effects and shoestring budget, it’s actually a pretty reverent adaptation). The 2000s Fantastic Four films were too unserious, then the 2015 Fantastic Four gritty reboot (forever saddled with the painful title Fant4stic) was too serious and scattershot. Couldn’t there be a healthy middle? There has been an excellent Fantastic Four film already except it was called The Incredibles. That 2004 Pixar movie followed a family of superheroes that mostly aligned with the powers of the foursome that originally made their debut for Marvel comics in 1961. It makes sense then for Marvel to borrow liberally from the style and approach of The Incredibles because, after all, it worked. There’s even a minor villain that is essentially a mole man living below the surface. Set on an alternate Earth, this new F4 relaunch eschews the thirty-something previous films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). You don’t need any prior understanding to follow the action, which is kept to under 105 minutes. The 1960s retro futurist visual aesthetic is a constant delight and adds enjoyment in every moment and every scene. The story is a modern parable: a planet-eating Goliath known as Galactus will consume all of Earth unless Reed Richards (Pedro Pascal) and Sue Storm (Vanessa Kirby), a.k.a. Mr. and Ms. Fantastic, give over their unborn son. The added context is that they have struggled with fertility issues, and now that at last they have a healthy baby on the cusp of being theirs, a cosmic giant wants to call dibs. It makes the struggle and stakes much more personal. It makes the foursome genuinely feel like a family trying to resolve this unthinkable ultimatum. I cared, and I even got teary-eyed at parts relating to the baby and his well-being, reflecting on my own parenting journey.

From a dramatic standpoint, this movie has it. From an action standpoint, it leaves a little to be desired. It incorporates the different powers well enough, but there are really only two large action set pieces with some wonky sci-fi mumbo jumbo. There’s a whimsical throwback that makes the movie feel like an extension of a Saturday morning cartoon show except for the whole give-me-your-baby-or-everybody-dies moral quandary. While I also appreciated its running time being lean, you can feel the absence of connective tissue. Take for instance The Thing (The Bear‘s Ebon Moss-Bachrach) having a possible romance with a teacher played by Natasha Lyonne (Poker Face). The first scene he introduces himself… and then he appears much later at her synagogue seeking her out specifically during mankind’s possible final hours. We’re missing out on the material that would make this personal connection make sense. The same with the world turning on the F4 once they learn they’ve put everyone in danger. It’s resolved pretty quickly by Sue giving one heartfelt speech. The movie already feels like it has plenty of downtime but I wanted a little more room to breathe. I was mostly underwhelmed by Pascal, who seems to be dialing down his natural charm, though his character has some inherently dark obsessions that intrigued me. He recognizes there is something wrong with him and the way his mind operates, and yet he hopes that his child will be a better version of himself, a relatable parental wish. There are glimmers of him being a more in-depth character but it’s only glimmers. The family downtime scenes were my favorite, and the camaraderie between all four actors is, well, fantastic (plus an adorable robot). Kirby (Napoleon) is the standout and the heart of the movie as a figure trying to square the impossible and desperate to hold onto the baby she’s dreamed of for so long.

The Fantastic Four: First Steps is an early step in a better direction. It’s certainly better than the prior attempts to launch Marvel’s first family of heroes, though this might not be saying much. It does more right than wrong, so perhaps the fourth time might actually be the charm.

Nate’s Grade: B-

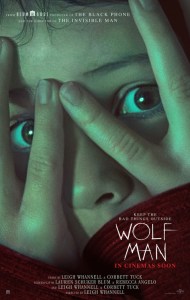

Wolf Man (2025)

I had high hopes for writer/director Leigh Whannell’s second take on the classic monsters after how thrilling and satisfying his take on the Invisible Man was in the early months of 2020. Werewolves have served as a fertile metaphorical ground for genre storytelling to cover such varied topics like coming of age, self-actualization, and addiction. Considering Whannell was able to use an invisible man to explore toxic masculinity and gaslighting, without losing sight of a monstrously entertaining movie, I was hoping for repeated success. Wolf Man is ostensibly about inherited curses and the relationships between fathers and children, but it’s really about dealing with flaring tempers and whether or not our shortcomings are a result of our genetic inheritance. It’s also about a family trapped in a cabin helplessly watching their father/husband transform into a dangerous beast. I suppose there’s something here about the cycles of trauma and abuse, anger as a sickness, but the problem with Whannell’s Wolf Man is that it all feels like an incomplete beginning. There are definite identifiable themes here, and a scenario that would lend to slow-building dread amid losing control over one’s sanity to become a monster against their loved ones. I just kept waiting for something more. The movie runs out of steam shockingly once it strands its family in the cabin. We’re treated to many scenes of Christopher Abbott, as the beleaguered father, blankly staring and then seeing his vision where people are highlighted with neon outlines. It’s a neat visual but what does it mean? I was waiting for more development, more character work, more culminating of themes, more… anything. It’s a lot of sitting around, like this promising genre movie had been hijacked by, like, some self-sabotaging arty Godard-obsessed filmmaker trying to Say Something with all the protracted scenes, pained silences, and repetition without revelation. It’s a surprisingly boring movie and, I repeat, it’s a werewolf movie. The makeup effects also make our titular monster look more like a shaved wolf, or a goblin rather than a lupine-centric creature of the night. I don’t even think there was a single shot of a full moon in the whole movie. Regardless, Wolf Man is a disappointing a d dull monster movie that’s too shaggy for its own good.

I had high hopes for writer/director Leigh Whannell’s second take on the classic monsters after how thrilling and satisfying his take on the Invisible Man was in the early months of 2020. Werewolves have served as a fertile metaphorical ground for genre storytelling to cover such varied topics like coming of age, self-actualization, and addiction. Considering Whannell was able to use an invisible man to explore toxic masculinity and gaslighting, without losing sight of a monstrously entertaining movie, I was hoping for repeated success. Wolf Man is ostensibly about inherited curses and the relationships between fathers and children, but it’s really about dealing with flaring tempers and whether or not our shortcomings are a result of our genetic inheritance. It’s also about a family trapped in a cabin helplessly watching their father/husband transform into a dangerous beast. I suppose there’s something here about the cycles of trauma and abuse, anger as a sickness, but the problem with Whannell’s Wolf Man is that it all feels like an incomplete beginning. There are definite identifiable themes here, and a scenario that would lend to slow-building dread amid losing control over one’s sanity to become a monster against their loved ones. I just kept waiting for something more. The movie runs out of steam shockingly once it strands its family in the cabin. We’re treated to many scenes of Christopher Abbott, as the beleaguered father, blankly staring and then seeing his vision where people are highlighted with neon outlines. It’s a neat visual but what does it mean? I was waiting for more development, more character work, more culminating of themes, more… anything. It’s a lot of sitting around, like this promising genre movie had been hijacked by, like, some self-sabotaging arty Godard-obsessed filmmaker trying to Say Something with all the protracted scenes, pained silences, and repetition without revelation. It’s a surprisingly boring movie and, I repeat, it’s a werewolf movie. The makeup effects also make our titular monster look more like a shaved wolf, or a goblin rather than a lupine-centric creature of the night. I don’t even think there was a single shot of a full moon in the whole movie. Regardless, Wolf Man is a disappointing a d dull monster movie that’s too shaggy for its own good.

Nate’s Grade: C

The Assistant (2020)

Jane (Julia Garner) is a young woman serving as an assistant to a high-profile film and TV producer, the kind of man with plenty of pull within the industry. She’s the first one into the production office and the last one out at night. Little by little, a larger picture forms of her temperamental, vindictive, and lecherous boss, especially as young women seeking to get ahead in the entertainment world as carted before him like sacrificial offerings. What will she do when the offending evidence becomes too much to ignore?

Jane (Julia Garner) is a young woman serving as an assistant to a high-profile film and TV producer, the kind of man with plenty of pull within the industry. She’s the first one into the production office and the last one out at night. Little by little, a larger picture forms of her temperamental, vindictive, and lecherous boss, especially as young women seeking to get ahead in the entertainment world as carted before him like sacrificial offerings. What will she do when the offending evidence becomes too much to ignore?

Where The Assistant lost me was in its lack or urgency with its storytelling. This is the slowest of slow burns, and it’s understandable, to a point, why this approach is the more realistic path. We’re watching the decades of inertia that make anyone standing up to harassment and abuse very difficult to find any traction or credibility. It’s much easier to just shrug it off, say “that’s just the way this awful man is,” laugh it off like some of his peers, ignore it like others, or compartmentalize, justifying your complicity as symptomatic of just how the industry works. I was waiting for the slow reveals to finally form a picture for our protagonist and push her into action, a desire to do something or say something about what she can no longer ignore or assist. The movie gets us to this point and, in its best scene, smacks her down for even seeking out this oversight. From there, the movie just becomes another repeat of what happened before, with more clues about the bad behavior of Jane’s boss, but it’s more of the same and then it just ends. I think writer/director Kitty Green (Casting JonBenet) was going for ongoing ambiguity whether or not Jane ultimately decides to leave her entry-level position or swallows her moral turpitude. However, there is a frustrating difference between an ending that is openly ambiguous and one that feels incomplete and lacking. After everything I went through, a little more definition by the end could have made the slog of work details more palatable.

This subject is bursting with pertinent urgency and social commentary and I feel like this movie is just missing so many important things to say and do in the name of misplaced indie understatement. Understatement can be fitting as an approach to real-life dilemmas but The Assistant is understated to its unfortunate detriment, traversing from subtlety into somnolence. More time is spent establishing the mundane details of Jane’s office duties than the harassment and protection afforded to her boss. I was expecting to collect little telling details, like the male assistants’ patterned ease of composing “apology e-mails” for whatever indignation the boss feels, but we’re absent a certain momentum throughout. The first thirty minutes is packed with moments like Jane making coffee, Jane tidying an office, Jane getting food, Jane answering phones, Jane microwaving a cheap dinner. We never see her at home from the moment she leaves in the opening of the film. It’s like the movie is saying she lives at the office or must if she is to get ahead in a broken system of people using people. The people passing through are superficial to us, never more than pretty faces, or important names coming and going on the peripheral. I was feeling crushed by the obsessive details of this work routine. I expected to establish a pattern, establish a baseline, and then move from there, forcing change or at least reflection. The mundane details are meant to convey the soul-crushing nature of Jane’s job, being on the bottom of an industry she’s desperate to break into, and how un-glamorous the life of the little people can be. But she’s also a gatekeeper of sorts for the line of future victims encountering her bad boss. There’s a degree of culpability there, and it’s never fully explored because of how underplayed every moment and every scene comes across, choosing mundanity over drama. I would not begrudge any viewer if they tuned out The Assistant after the first half hour of work.

This subject is bursting with pertinent urgency and social commentary and I feel like this movie is just missing so many important things to say and do in the name of misplaced indie understatement. Understatement can be fitting as an approach to real-life dilemmas but The Assistant is understated to its unfortunate detriment, traversing from subtlety into somnolence. More time is spent establishing the mundane details of Jane’s office duties than the harassment and protection afforded to her boss. I was expecting to collect little telling details, like the male assistants’ patterned ease of composing “apology e-mails” for whatever indignation the boss feels, but we’re absent a certain momentum throughout. The first thirty minutes is packed with moments like Jane making coffee, Jane tidying an office, Jane getting food, Jane answering phones, Jane microwaving a cheap dinner. We never see her at home from the moment she leaves in the opening of the film. It’s like the movie is saying she lives at the office or must if she is to get ahead in a broken system of people using people. The people passing through are superficial to us, never more than pretty faces, or important names coming and going on the peripheral. I was feeling crushed by the obsessive details of this work routine. I expected to establish a pattern, establish a baseline, and then move from there, forcing change or at least reflection. The mundane details are meant to convey the soul-crushing nature of Jane’s job, being on the bottom of an industry she’s desperate to break into, and how un-glamorous the life of the little people can be. But she’s also a gatekeeper of sorts for the line of future victims encountering her bad boss. There’s a degree of culpability there, and it’s never fully explored because of how underplayed every moment and every scene comes across, choosing mundanity over drama. I would not begrudge any viewer if they tuned out The Assistant after the first half hour of work.

There is a noticeable feeling of dread and discomfort in the movie, but without variation or escalation it feels almost like a horror movie where we’re stuck with the person on the other wall of the action just briefly overhearing things. Imagine Rosemary’s Baby but if you were one of the neighbors just wondering what was going on. There’s an important message here and the point of view of an up-and-coming young woman as the assistant to a Harvey Weisntein-esque monster and her moral quandary of how far to ignore and how much she is willing to suffer is great. That’s a terrific, dramatically urgent starting point, and yet The Assistant is too muted and padded. There’s a remarkably thin amount of drama during these 85 minutes, with the more intriguing and disturbing action kept in the realm of innuendo and suspicion. It makes the final movie feel like the real movie is on the fringes of what we’re seeing and we just need to nudge back to the drama.

There is one fantastic scene in The Assistant and it happens at the end of Act Two, and that’s when Jane finally seeks out the HR rep, Wilcock (Matthew Macfadyen). You sense just how much she wants to say but how much she feels the need to still be guarded, so minute by minute she tries a few more scant details, all that’s needed to limit her vulnerability and exposure. Wilcock seems like he might just take her words seriously, and then he interrupts to answer a phone call, and it’s an obnoxiously unimportant call and his behavior merges into just “one of the guys.” From there, he turns the heat on Jane, laying out her circumstantial claims and questioning what her future plans are and if this is the best course of action to see those plans through. It’s the company line sort of pressure and you feel Jane retreat within herself as soon as this potential ally becomes just another cog in a system to enable abusers. Garner (Ozark) is never better than in this scene, where the understated nature of the film, and her performance, really hits the hardest. It’s the quiet resignation and heartbreaking realization that the system is designed to protect itself. I wish the concluding twenty minutes had more of the drama that this scene points to as its direction.

There is one fantastic scene in The Assistant and it happens at the end of Act Two, and that’s when Jane finally seeks out the HR rep, Wilcock (Matthew Macfadyen). You sense just how much she wants to say but how much she feels the need to still be guarded, so minute by minute she tries a few more scant details, all that’s needed to limit her vulnerability and exposure. Wilcock seems like he might just take her words seriously, and then he interrupts to answer a phone call, and it’s an obnoxiously unimportant call and his behavior merges into just “one of the guys.” From there, he turns the heat on Jane, laying out her circumstantial claims and questioning what her future plans are and if this is the best course of action to see those plans through. It’s the company line sort of pressure and you feel Jane retreat within herself as soon as this potential ally becomes just another cog in a system to enable abusers. Garner (Ozark) is never better than in this scene, where the understated nature of the film, and her performance, really hits the hardest. It’s the quiet resignation and heartbreaking realization that the system is designed to protect itself. I wish the concluding twenty minutes had more of the drama that this scene points to as its direction.

The Assistant had a lot of things going for it as a queasy indie drama and it’s still well acted with searing details and a strong sense of authenticity. I feel like that authenticity, however, gets in the way of telling a more compelling and affecting story. I’m here to see the pressure, torment, and decision-making of a young woman put in an unenviable position, and what I was given was an hour of office tasks and eavesdropping. It’s got its moments but it left me wanting more.

Nate’s Grade: B-

You must be logged in to post a comment.