Blog Archives

Batman Begins (2005) [Review Re-View]

Originally released June 15, 2005:

Originally released June 15, 2005:

I have been a Batman fan since I was old enough to wear footy pajamas. I watched the campy Adam West TV show all the time, getting sucked into the lead balloon adventures. Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman was the first PG-13 film I ever saw, and I watched it so many times on video that I have practically worn out my copy. Batman Returns was my then most eagerly anticipated movie of my life, and even though it went overboard with the dark vision, I still loved it. Then things got dicey when Warner Brothers decided Batman needed to lighten up. I was only a teenager at the time, but I distinctly remember thinking, “You’re telling the Dark Knight to lighten up?” Director Joel Schumacher’s high-gloss, highly stupid turn with Batman Forever pushed the franchise in a different direction, and then effectively killed it with 1997’s abomination, Batman and Robin. I mean these films were more worried about one-liners and nipples on the Bat suits. Nipples on the Bat suits, people! Is Batman really going, “Man, you know, I’d really like to fight crime today but, whoooo, my nipples are so chaffed. I’m gonna sit this one out”?

For years Batman languished in development hell. Warner Bothers licked their wounds and tried restarting their franchise again and again, only to put it back down. Then around 2003 things got exciting. Writer/director Christopher Nolan was announced to direct. Nolan would also have creative control. Surely, Warner Brothers was looking at what happened when Columbia hired Sam Raimi (most known for low-budget splatterhouse horror) for Spider-Man and got out of his way. After Memento (My #1 movie of 2001) and Insomnia (My #5 movie of 2002), Nolan tackles the Dark Night and creates a Batman film that’s so brilliant that I’ve seen it three times and am itching to go again.

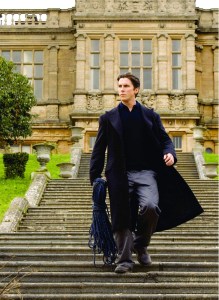

The film opens with a youthful Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) in a Tibetan prison. He’s living amongst the criminal element searching for something within himself. Henri Ducard (Liam Neeson) offers Bruce the chance to be taught under the guidance of the mysterious Ra’s Al Ghul (Ken Watanabe), the leader of the equally mysterious warrior clan, The League of Shadows. Under Ducard’s direction, Bruce confronts his feelings of guilt and anger over his parents’ murder and his subsequent flee from his hometown, Gotham City. He masters his training and learns how to confront fear and turn it to his advantage. However, Bruce learns that the League of Shadows has its judicial eyes set on a crime ridden Gotham, with intentions to destroy the city for the betterment of the world. Bruce rebels and escapes the Tibetan camp and returns to Gotham with his own plans of saving his city.

The film opens with a youthful Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) in a Tibetan prison. He’s living amongst the criminal element searching for something within himself. Henri Ducard (Liam Neeson) offers Bruce the chance to be taught under the guidance of the mysterious Ra’s Al Ghul (Ken Watanabe), the leader of the equally mysterious warrior clan, The League of Shadows. Under Ducard’s direction, Bruce confronts his feelings of guilt and anger over his parents’ murder and his subsequent flee from his hometown, Gotham City. He masters his training and learns how to confront fear and turn it to his advantage. However, Bruce learns that the League of Shadows has its judicial eyes set on a crime ridden Gotham, with intentions to destroy the city for the betterment of the world. Bruce rebels and escapes the Tibetan camp and returns to Gotham with his own plans of saving his city.

With the help of his trusted butler Alfred (Michael Caine), Bruce sets out to regain his footing with his family’s company, Wayne Enterprises. The company is now under the lead of an ethically shady man (Rutger Hauer) with the intentions of turning the company public. Bruce befriends Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman), the company’s gadget guru banished to the lower levels of the basement for raising his voice. Bruce gradually refines his crime fighting efforts and becomes the hero he’s been planning on since arriving home.

Gotham is in bad shape too. Rachel Dawes (Katie Holmes), a childhood friend to Bruce, is a prosecutor who can’t get anywhere when crime lords like Falcone (Tom Wilkinson) are controlling behind the scenes. Most of the police have been bought off, but Detective Gordon (Gary Oldman) is the possibly the city’s last honest cop, and he sees that Batman is a figure trying to help. Dr. Crane (Cillian Murphy) is a clinical psychologist in cahoots with Falcone. Together they’re bringing in drug shipments for a nefarious plot by The Scarecrow, a villain that uses a hallucinogen to paralyze his victims with vivid accounts of their own worst fears. Bruce is the only one who can unravel the pieces of this plot and save the people of Gotham City.

Nolan has done nothing short of resurrecting a franchise. Previous films never treated Batman as an extraordinary character; he was normal in an extraordinary world. Batman Begins places the character in a relatively normal environment. This is a brooding, intelligent approach that all but erases the atrocities of previous Batman incarnations. Nolan presents Bruce Wayne’s story in his typical nonlinear fashion, but really gets to the meat and bone of the character, opening up the hero to new insights and emotions, like his suffocating guilt over his parents murder.

Nolan has done nothing short of resurrecting a franchise. Previous films never treated Batman as an extraordinary character; he was normal in an extraordinary world. Batman Begins places the character in a relatively normal environment. This is a brooding, intelligent approach that all but erases the atrocities of previous Batman incarnations. Nolan presents Bruce Wayne’s story in his typical nonlinear fashion, but really gets to the meat and bone of the character, opening up the hero to new insights and emotions, like his suffocating guilt over his parents murder.

Nolan and co-writer David S. Goyer (the Blade trilogy) really strip away the decadence of the character and present him as a troubled being riddled with guilt and anger. Batman Begins is a character piece first and an action movie second. The film is unique amongst comic book flicks for the amount of detail and attention it pays to characterization, even among the whole sprawling cast. Nolan has assembled an incredible cast and his direction is swimming in confidence. He’s a man that definitely knows what he’s doing, and boy oh boy, is he doing it right. Batman Begins is like a franchise colonic.

This is truly one of the finest casts ever assembled. Bale makes an excellent gloomy hero and really transforms into something almost monstrous when he’s taking out the bad guys. He’s got great presence but also a succinct intensity to nail the quieter moments where Bruce Wayne battles his inner demons. Caine (The Cider House Rules, The Quiet American) is incomparable and a joy to watch, and his scenes with the young Bruce actually had me close to tears. This is by far the first time a comic book movie even had me feeling something so raw and anything close to emotional. Neeson excels in another tough but fair mentor role, which he seems to be playing quite a lot of lately (Kingdom of Heaven, Star Wars Episode One). Freeman steals every scene he’s in as the affable trouble causer at Wayne Enterprises, and he also gets many of the film’s best lines. Oldman (The Fifth Element, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban) disappears into his role as Gotham’s last good cop. If ever there was a chameleon (and their name wasn’t Benicio del Toro), it is Oldman. Holmes works to the best of her abilities, which means she’s “okay.”

The cast of villains are uniformly excellent, with Wilkinson’s (In the Bedroom) sardonic Chicagah accented mob boss, to Murphy’s (28 Days Later…) chilling scientific approach to villainy, to Watanabe’s (The Last Samurai) cold silent stares. Even Rutger Hauer (a man experiencing a career renaissance of his own) gives a great performance. Seriously, for a comic book movie this is one of the better acted films of the year. And that’s saying a lot.

Batman Begins is such a serious film that it almost seems a disservice to call it a “comic book movie.” There are no floating sound effects cards and no nipples on the Bat suits. Nolan really goes about answering the tricky question, “What kind of man would become a crime-fightin’ super hero?” Batman Begins answers all kinds of questions about the minutia of the Dark Knight in fascinating ways, yet the film remains grounded in reality. The Schumacher Batmans (and God save us from them) were one large, glitzy, empty-headed Las Vegas entertainment show. No explanation was given to characters or their abilities. Likewise, the Gothic and opulent Burton Batmans had their regrettable leaps of logic as well. It’s hard not to laugh at the end of Batman Returns when Oswald Cobblepot (a.k.a. The Penguin) gets a funeral march from actors in emperor penguin suits. March of the Penguins it ain’t. Nolan’s Batman is the dead-serious affair comic book lovers have been holding their breath for.

The action is secondary to the story, but Batman Begins still has some great action sequences. Most memorable is a chase sequence between Gotham police and the Batmobile which goes from rooftop to rooftop at one point. Nolan even punctuates the sequence with some fun humor from the police (“It’s a black … tank.”). The climactic action sequence between good guy and bad guy is dutifully thrilling and grandiose in scope. Nolan even squeezes in some horror elements into the film. Batman’s first emergence is played like a horror film, with the caped crusader always around another turn. The Scarecrow’s hallucinogen produces some creepy images, like a face covered in maggots or a demonic bat person.

The action is secondary to the story, but Batman Begins still has some great action sequences. Most memorable is a chase sequence between Gotham police and the Batmobile which goes from rooftop to rooftop at one point. Nolan even punctuates the sequence with some fun humor from the police (“It’s a black … tank.”). The climactic action sequence between good guy and bad guy is dutifully thrilling and grandiose in scope. Nolan even squeezes in some horror elements into the film. Batman’s first emergence is played like a horror film, with the caped crusader always around another turn. The Scarecrow’s hallucinogen produces some creepy images, like a face covered in maggots or a demonic bat person.

There are only a handful of flaws that make Batman Begins short of being the best comic book movie ever. The action is too overly edited to see what’s happening. Whenever Batman gets into a fight all you can see are quick cuts of limbs flailing. My cousin Jennifer got so frustrated with the oblique action sequences that she just waited until they were over to see who won (“Oh, Batman won again. There you go.”). Nolan’s editing is usually one of his strong suits; much of Memento’s success was built around its airtight edits. He needs to pull the camera back and let the audience see what’s going on when Batman gets physical.

Another issue is how much plot Batman Begins has to establish. This is the first Batman film to focus solely on Batman and not some colorful villain. Batman doesn’t even show up well into an hour into the movie. As a result, Batman Begins perfects the tortured psychology of Bruce Wayne but leaves little time for villains. The film plays a shell game with its multiple villains, which is fun for awhile. The Scarecrow is really an intriguing character and played to gruesome effect by the brilliant Cillian Murphy. It’s a shame Batman Begins doesn’t have much time to develop and then play with such an intriguing bad guy.

Batman Begins is a reboot for the film franchise. Nolan digs deep at the tortured psyche of Bruce Wayne and come up with a treasure trove of fascinating, exciting, and genuinely engrossing characters. Nolan’s film has a handful of flaws, most notably its oblique editing and limited handling of villains, but Batman Begins excels in storytelling and crafts a superbly intelligent, satisfying, riveting comic book movie. The best bit of praise I can give Batman Begins is that I want everyone responsible to return immediately and start making a host of sequels. This is a franchise reborn and I cannot wait for more of it.

Nate’s Grade: A

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

Batman Begins could have also been subtitled, Christopher Nolan Begins. The eponymous writer/director, who has defined the twenty-first century in the realm of artful blockbusters perhaps more than anyone, had made three movies prior to this big moment. He began with 1998’s Following, but it was 2001’s Memento that got everyone’s attention. His immediate follow-up, 2002’s Insomnia, is a very good movie, and actually a better version than the Nordic original, but it was really proof for Warner Brothers that this clever indie guy could handle a larger studio project. In the early 2000s, Warner Brothers was desperate to relaunch Batman after the demise of the franchise with 1997’s ultra campy Batman & Robin, and many filmmakers were courted to relaunch the Dark Knight. It was literally a month after rejecting Joss Whedon’s reboot pitch that in January 2003, the studio announced Nolan was attached and writing the screenplay with David S. Goyer, who was hot off the Blade movies and seemed to have cracked the code for making more mature comic book movie adaptations. What followed was a dramatic reworking of Batman, grounding him and his world in realism and opening Bruce Wayne up for a closer psychological examination, giving the man behind the mask an opportunity to be the actual focus for once. The results reinvigorated the dormant franchise, provided a path for superhero reboots in a post-9/11 landscape, and launched Nolan on his ascendant trajectory to being the biggest blockbuster voice of the modern era.

Batman was a popular character in DC comics (note: DC stands for “Detective Comics,” so saying, “DC comics” is like saying, “Detective Comics comics,” much like the way the “Sahara” means “desert”) from his inception in in 1939, but he was always well behind Superman, the golden boy. The campy Adam West TV series was popular, and actually saved the comic from being discontinued, but it wasn’t until 1989 that Batman became the most popular superhero. The darkness and edge of Batman was more appealing for the modern masses, and paired with Tim Burton, it proved the new levels of studio blockbusters after the steep decline from the Christopher Reeve Superman movies. Ever since, we’ve had over ten live-action headlining Batman movies and only four Superman live-action movies, now five thanks to James Gunn’s recent high-flying addition. Much as the Burton 1989 Batman brought the character to an even bigger height of modern stardom, it was Nolan who likewise took the character and made it an even bigger spectacle that also steered the zeitgeist of what superhero movies could be.

Batman was a popular character in DC comics (note: DC stands for “Detective Comics,” so saying, “DC comics” is like saying, “Detective Comics comics,” much like the way the “Sahara” means “desert”) from his inception in in 1939, but he was always well behind Superman, the golden boy. The campy Adam West TV series was popular, and actually saved the comic from being discontinued, but it wasn’t until 1989 that Batman became the most popular superhero. The darkness and edge of Batman was more appealing for the modern masses, and paired with Tim Burton, it proved the new levels of studio blockbusters after the steep decline from the Christopher Reeve Superman movies. Ever since, we’ve had over ten live-action headlining Batman movies and only four Superman live-action movies, now five thanks to James Gunn’s recent high-flying addition. Much as the Burton 1989 Batman brought the character to an even bigger height of modern stardom, it was Nolan who likewise took the character and made it an even bigger spectacle that also steered the zeitgeist of what superhero movies could be.

While 2008’s The Dark Knight is widely regarded as Nolan’s best movie in his trilogy, I actually consider Batman Begins his best. That is no insult to The Dark Knight, a wildly entertaining movie that is something truly special every second Heath Ledger is onscreen with his magnetic portrayal of the Joker, a modern-day anarchist seeking validation from the costumed crusader who “changed all the rules.” It’s a good movie with some wonky plotting you don’t think of as long as Ledger is lighting it up, but that first movie was a proof of concept that Batman can carry his own movie. It humanizes the character and strips him down before gradually putting him back together, explaining how this character assembles the tools of his trade and the allies that help support his mission. It’s a satisfying series of trial and error that proves entertaining as we watch the myth of Batman take shape. This first movie is about the formation of Batman, whereas the second is about the escalating consequences of introducing a well-armed vigilante into the bloodstream of organized crime. The first film is the most complete movie, and while it has some flights of fancy like a secret ninja conspiracy, it still works on a relatively grounded level. For the first time in perhaps the character’s film history, you will find yourself caring about the character. That is an accomplishment, and you can feel it when Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) merely standing amidst a swarm of bats is played as a turning point of self-actualization. And it works. This is Nolan’s best Batman.

We don’t even get our first glimpse of Batman as we know him until halfway through the movie. That’s a lot of waiting for a movie with “Batman” as the first word of its title. Even twenty years later, I find the build-up satisfying, watching Bruce Wayne put together the pieces that we associate with Batman, from his cowl to his cape to his suit to the Batmobile, which is practically an all-terrain tank. Finding interesting ways to generate these familiar parts, iconography, and allies makes an invigorating drama that is better than the more action-heavy second half of the movie. It’s still fun and enjoyable how Nolan is able to bring together so many elements with payoffs. This is Nolan’s first blockbuster and he proves that he has an innate feel for popcorn entertainment, knowing how to structure and pace the action and intrigue and laying in those setups and payoffs along with winning character beats and themes. He shows how he can make the moments matter to form an even greater whole. That’s the lasting impact of Batman Begins, where every moment helps to build the mystique of the superhero but also the psychology of Wayne and what motivates a man to dress up and punch dudes for a living.

We don’t even get our first glimpse of Batman as we know him until halfway through the movie. That’s a lot of waiting for a movie with “Batman” as the first word of its title. Even twenty years later, I find the build-up satisfying, watching Bruce Wayne put together the pieces that we associate with Batman, from his cowl to his cape to his suit to the Batmobile, which is practically an all-terrain tank. Finding interesting ways to generate these familiar parts, iconography, and allies makes an invigorating drama that is better than the more action-heavy second half of the movie. It’s still fun and enjoyable how Nolan is able to bring together so many elements with payoffs. This is Nolan’s first blockbuster and he proves that he has an innate feel for popcorn entertainment, knowing how to structure and pace the action and intrigue and laying in those setups and payoffs along with winning character beats and themes. He shows how he can make the moments matter to form an even greater whole. That’s the lasting impact of Batman Begins, where every moment helps to build the mystique of the superhero but also the psychology of Wayne and what motivates a man to dress up and punch dudes for a living.

It also helps that this movie is perfectly cast from top to bottom. Bale was as sturdy a center as you could get. He only went on to be nominated for four Oscars, winning once for 2010’s The Fighter (and should have won in 2018 as Dick Cheney in Vice). He’s long been known for transforming himself completely with his roles. Between 2004’s The Machinist and Batman Begins, there’s a 100-pound difference in Bale’s physique. His performances can get too easily overlooked because of the gimmicky body transformations, but Bale has been one of our most consistent and interesting actors for these last twenty years. Getting Michael Caine (Oscar winner), Morgan Freeman (Oscar winner), Gary Oldman (future Oscar winner), Cillian Murphy (future Oscar winner), Tom Wilkinson (future Oscar nominee), Neeson, Wantanabe, and even Rutger Hauer to be in your movie is obviously a setup for greatness. Nolan and company even get the smallest roles right, like hiring Rade Serbedzija (Snatch, Eyes Wide Shut) just as a homeless man Bruce gives his coat to. He’s only in two scenes for maybe thirty seconds but you got this actor for that part. The odd one out is Katie Holmes as Bruce’s childhood friend who becomes a crusading prosecutor. It’s not a knock on Holmes but simply her character’s role in the story. There’s also the knowledge that this role was recast with Maggie Gyllenhaal in the 2008 sequel, so one wonders what Gyllenhaal would have been like here. I like Holmes as an actress but Maggie Gyllenhaal is a definite upgrade.

Allow me to question the mission of the League of Shadows and good ole Ra’s al Ghul (Ken Wantanabe, but really Liam Neeson). They are a secret order of ninjas trained to fight injustice through extreme measures. They’ve been in existence for hundreds of years, maybe thousands, and claim to have contributed to the destruction of such empires as Rome and Constantinople when they became breeding grounds of injustice. Their next target is Gotham and they become our returning antagonists for the climax, Batman having to take down his mentor. This philosophy purports to link criminality with borders, alleging that criminals are only encouraged by the corrupt institutions of the city. If Rome can no longer support a thriving criminal network, the assumption is that crime goes away. You take away the platform and, voila, injustice and criminality are gone. That’s quite an oversimplification. You could make the argument that destroying a corrupt city makes it harder for criminals to find footing, but does it eliminate crime or just force it to migrate elsewhere? This also assumes that only cities are cesspools for criminality and corruption; look into the Sackler-lead network of pill mills dotting rural America. I guess drug and sex trafficking only exist in urban America, right? The League of Shadows have a bad idea forming a bad philosophy that is being applied badly, and I just wanted to point this out.

Allow me to question the mission of the League of Shadows and good ole Ra’s al Ghul (Ken Wantanabe, but really Liam Neeson). They are a secret order of ninjas trained to fight injustice through extreme measures. They’ve been in existence for hundreds of years, maybe thousands, and claim to have contributed to the destruction of such empires as Rome and Constantinople when they became breeding grounds of injustice. Their next target is Gotham and they become our returning antagonists for the climax, Batman having to take down his mentor. This philosophy purports to link criminality with borders, alleging that criminals are only encouraged by the corrupt institutions of the city. If Rome can no longer support a thriving criminal network, the assumption is that crime goes away. You take away the platform and, voila, injustice and criminality are gone. That’s quite an oversimplification. You could make the argument that destroying a corrupt city makes it harder for criminals to find footing, but does it eliminate crime or just force it to migrate elsewhere? This also assumes that only cities are cesspools for criminality and corruption; look into the Sackler-lead network of pill mills dotting rural America. I guess drug and sex trafficking only exist in urban America, right? The League of Shadows have a bad idea forming a bad philosophy that is being applied badly, and I just wanted to point this out.

The legacy of the Nolan Batman trilogy carries on twenty years later. They are considered some of the biggest blockbusters of the twenty-first century, but it’s also the beginning of the meteoric ascent of Nolan. 2006’s The Prestige, likely his most underrated film, is the last of the Before Movies. Ever since, every Nolan movie has been an event, even ones that step back into more personal and cerebral spaces, like 2023’s runaway Oscar juggernaut, the billion-dollar three-hour biopic, Oppenheimer. He’s become one of a very select few filmmakers whose very name is a selling point to the general public regardless of whatever the project might be (joining Spielberg, Tarantino, James Cameron, and maybe Jordan Peele at this point). I agree with my 2005 criticisms that Nolan is not an expert handler of action. He’s tremendous at atmosphere, with judicious editing and eye-popping visuals, but action construction is not his forte, even after several more action movies to his name. I was much more entertained by the horror sequences from the Scarecrow fear toxin than I was by the straight action. I do wish the villains had more time, especially the Scarecrow, but it’s a result of having so much more plot to do, and centering around Bruce Wayne and his personal journey to superhero-dom means everything serves this streamlined goal.

I saw Batman Begins three times in the theater back in 2005. As a longtime Batman fan, a kid whose first VHS tape was the 89 Batman, who obsessed over every detail for the Batman Returns release, who religiously watched the excellent 90s animated series, I felt a sense of elation that this was a movie that got it. Nolan and his team got Batman and did him justice that had been denied for years. We now likely live in a universe where we’ll never be more than four years away from another live-action Batman movie or appearance. I enjoy the Matt Reeves’ Batman era we’re currently living through, another gritty take favoring realism and depth of character to comic book pulp heroics. The Nolan movies walked so that the Reeves films could fly. If you’re a fan of Batman in the real world, then these last twenty years have been resplendent (Ben Affleck was the highlight of Batman vs. Superman – no joke). It’s interesting to see that convergent point in 2005, where Nolan re-imagined the character for today, and also where Christopher Nolan became the signature blockbuster filmmaker we now freely associate him to be. Batman Begins is a comic book movie that feels so well-suited for the times as well as all time. It’s still smashing.

I saw Batman Begins three times in the theater back in 2005. As a longtime Batman fan, a kid whose first VHS tape was the 89 Batman, who obsessed over every detail for the Batman Returns release, who religiously watched the excellent 90s animated series, I felt a sense of elation that this was a movie that got it. Nolan and his team got Batman and did him justice that had been denied for years. We now likely live in a universe where we’ll never be more than four years away from another live-action Batman movie or appearance. I enjoy the Matt Reeves’ Batman era we’re currently living through, another gritty take favoring realism and depth of character to comic book pulp heroics. The Nolan movies walked so that the Reeves films could fly. If you’re a fan of Batman in the real world, then these last twenty years have been resplendent (Ben Affleck was the highlight of Batman vs. Superman – no joke). It’s interesting to see that convergent point in 2005, where Nolan re-imagined the character for today, and also where Christopher Nolan became the signature blockbuster filmmaker we now freely associate him to be. Batman Begins is a comic book movie that feels so well-suited for the times as well as all time. It’s still smashing.

Re-Review Grade: A

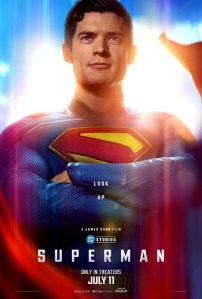

Superman (2025)

Has the world ever needed Superman more? I don’t know about you, but I could really use a symbol of good right now who represents the best of us, fighting for justice and protecting the innocent against the diabolical in power that seek to profit and prey upon the vulnerable. Vulture film critic Allison Wilmore has a fantastic headline for her review: “Superman [the movie] isn’t trying to be political. We just have real-life super villains now.” James Gunn, the quirky filmmaker who made us fall in love with a raccoon and a tree in the Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy, ascended to be head of DC movies in 2022, and he eyed reigniting Superman as the top priority, selecting himself as writer and director. It’s a lot of pressure to rebuild the DC movie brand by yourself, as there are only two other movies with scheduled release dates currently. This movie could make or break the fledgling DC Universe (DCU) rebuild soon after the smoking demise of the DC Extended Universe (2013-2023), informally dubbed the Snyderverse. Fortunately, Gunn’s take on the boy in blue is a reminder why this character has lasted so long and why the world still needs a symbol of hope.

Has the world ever needed Superman more? I don’t know about you, but I could really use a symbol of good right now who represents the best of us, fighting for justice and protecting the innocent against the diabolical in power that seek to profit and prey upon the vulnerable. Vulture film critic Allison Wilmore has a fantastic headline for her review: “Superman [the movie] isn’t trying to be political. We just have real-life super villains now.” James Gunn, the quirky filmmaker who made us fall in love with a raccoon and a tree in the Guardians of the Galaxy trilogy, ascended to be head of DC movies in 2022, and he eyed reigniting Superman as the top priority, selecting himself as writer and director. It’s a lot of pressure to rebuild the DC movie brand by yourself, as there are only two other movies with scheduled release dates currently. This movie could make or break the fledgling DC Universe (DCU) rebuild soon after the smoking demise of the DC Extended Universe (2013-2023), informally dubbed the Snyderverse. Fortunately, Gunn’s take on the boy in blue is a reminder why this character has lasted so long and why the world still needs a symbol of hope.

Superman (David Corenswet) a.k.a. Clark Kent, has been a defender of Metropolis for three years now. He’s romantically involved with ace reporter Lois Lane (Rachel Bosnahan), who knows his secret identity but still chides Clark on somehow getting all those “exclusive interviews” with Superman. He’s also been a thorn in billionaire industrialist Lex Luthor’s (Nicholas Hoult) side and become an obsession of his. The world is still debating Superman’s unexpected intervention, thwarting a powerful military from invading its neighbor’s sovereign border (very reminiscent of Russian aggression). The U.S. government needs actionable proof that Superman is a threat, and Lex is determined to eliminate the alien for good.

Amazingly, this movie feels like the second in a series rather than a reboot kickoff. From the opening text, Gunn drops us into this world already in progress. We’re skipping over the origin story, the character introductions, and all the table-setting that comprises many first films in franchises. It’s usually that second film that really takes advantage of the setup and patience of the first movie, expanding the world and deepening the character relationships and conflicts. Gunn has mercifully skipped over all that and gotten us right to the good stuff. The opening minutes of the movie drop us into a super-powered battle with the declaration that this is the first time our Superman has lost, and that beginning follows the most powerful alien on Earth having to patch up his injuries. I think that’s a very intriguing first impression, but I’ll detail more of that in a later paragraph. The world that Gunn establishes already feels well underway but the story is still accessible and the supporting characters have meaning within this world. This is a world that has been used to super heroes, a.k.a. metahumans, for some time, so when Superman finally dons his red underwear it’s not a complete shocker. This is not necessarily a reality where one super-charged character has reconfigured mankind’s entire sense of identity. The world is accustomed and adapted to extraordinary figures and monsters. This is where the Justice Gang comes in (Green Lantern, Hawkgirl, and Mr. Terrific). They’re the corporate supes, the ones called in to sign autographs, smile for pictures, and save the day for good P.R. Perhaps that’s too flippant, but the trio of established heroes doesn’t feel the same call to activism like Superman. It’s hard to fully articulate, so bear with me dear reader, but Gunn’s Superman already feels fully established, with the figure known, his relationship with Lois already in play, and Lex having already put nefarious time, research, and lots of money into combating this super obstacle with his own lethal experiments. With Gunn, there’s no time to waste. It’s already fully formed from his imagination, and the parts have their reasoning and meaning, making the whole much more satisfying.

Amazingly, this movie feels like the second in a series rather than a reboot kickoff. From the opening text, Gunn drops us into this world already in progress. We’re skipping over the origin story, the character introductions, and all the table-setting that comprises many first films in franchises. It’s usually that second film that really takes advantage of the setup and patience of the first movie, expanding the world and deepening the character relationships and conflicts. Gunn has mercifully skipped over all that and gotten us right to the good stuff. The opening minutes of the movie drop us into a super-powered battle with the declaration that this is the first time our Superman has lost, and that beginning follows the most powerful alien on Earth having to patch up his injuries. I think that’s a very intriguing first impression, but I’ll detail more of that in a later paragraph. The world that Gunn establishes already feels well underway but the story is still accessible and the supporting characters have meaning within this world. This is a world that has been used to super heroes, a.k.a. metahumans, for some time, so when Superman finally dons his red underwear it’s not a complete shocker. This is not necessarily a reality where one super-charged character has reconfigured mankind’s entire sense of identity. The world is accustomed and adapted to extraordinary figures and monsters. This is where the Justice Gang comes in (Green Lantern, Hawkgirl, and Mr. Terrific). They’re the corporate supes, the ones called in to sign autographs, smile for pictures, and save the day for good P.R. Perhaps that’s too flippant, but the trio of established heroes doesn’t feel the same call to activism like Superman. It’s hard to fully articulate, so bear with me dear reader, but Gunn’s Superman already feels fully established, with the figure known, his relationship with Lois already in play, and Lex having already put nefarious time, research, and lots of money into combating this super obstacle with his own lethal experiments. With Gunn, there’s no time to waste. It’s already fully formed from his imagination, and the parts have their reasoning and meaning, making the whole much more satisfying.

Another way to differentiate this Superman is less from his strength than his vulnerabilities. This is a character long regarded as overly powerful, too indestructible and therefore lacking realtability. Well with Gunn’s version, here is a Superman that gets beat up. A lot. Ben Affleck’s Batman pointedly asked Henry Cavill’s Supes, “Do you bleed?” Gunn has answered in the affirmative. Much like Matt Reeves’ 2022 Batman, we get a work-in-progress superhero that is still feeling out how to best be a superhero. It’s a version that takes lots of lumps and Gunn finds interesting ways to test Superman’s limits, both emotionally and physically. The introduction of nanites into orifices certainly provides nods to Gunn’s body horror roots. While this is a Superman that gets knocked around quite a bit, his biggest vulnerability is his doubt. He’s simply trying to do good and save lives regardless of the political ramifications, but the world and its people, and especially their fears and paranoia of an Other, are more complicated. Superman explains he intervened in an international border war for the simple reason of saving lives. When Lois pushes him in a practice on-the-record interview, during one of the better scenes, about his decision-making, thinking through the consequences, consulting with world leaders and the like, he gets flustered and says there wasn’t time. All he wanted to do was save lives that would have been lost, so why is the rest of the world having a hard time with that? Over the course of those two hours and change, we watch this Superman battle through his self-doubts in a very real and compelling way that I don’t feel like any other Superman movie has better demonstrated. This is a world already rife with heroes, but is it better with a Superman? Is his existence a net positive?

Gunn truly understands the character in a way that Zack Snyder never did. With Man of Steel and the subsequent film appearances, we were given a Superman that didn’t really want to be Superman. He was an overburdened superior being tasked with serving as mankind’s savior, and came across as annoyed. That version of Pa Kent famously told his super son that it might have been best if Clark had just let a bus full of kids die to keep his secret. Thanks for the life lesson, dad, and oh, by the way, your sacrifice was ultimately meaningless when your entire worldview was proven wrong by the end of Man of Steel. Regardless, here is a Superman that is unabashedly sincere and even a little corny. That’s who this character is, a do-gooder wanting to inspire others and wanting to save all life, even the villains, even the wildlife (my theater took special note when Superman saved a squirrel from being crushed). Snyder’s Superman was part of an entire Metropolis 9/11 of horrible collateral damage disaster porn. Gunn’s Superman works hard to make sure the giant kaiju monster, when teetering over, doesn’t fall on any building to protect the people inside. This is also a Superman that feels compelled to be a hero, to do better with his super gifts, and to keep trying even when he fails, that there can be dignity in losing a fight but continuing on because you know that fight is worth it. The depiction of Superman/Clark makes him feel much more a character worth closer examination. He’s not a detached god feeling above these petty mortals always needing saving. The real super power is his empathy and desire to help others, and that may sound corny, but Superman is too, and that’s completely fine in a world that would be better if we had more Supermans and fewer wannabe super villains.

Gunn truly understands the character in a way that Zack Snyder never did. With Man of Steel and the subsequent film appearances, we were given a Superman that didn’t really want to be Superman. He was an overburdened superior being tasked with serving as mankind’s savior, and came across as annoyed. That version of Pa Kent famously told his super son that it might have been best if Clark had just let a bus full of kids die to keep his secret. Thanks for the life lesson, dad, and oh, by the way, your sacrifice was ultimately meaningless when your entire worldview was proven wrong by the end of Man of Steel. Regardless, here is a Superman that is unabashedly sincere and even a little corny. That’s who this character is, a do-gooder wanting to inspire others and wanting to save all life, even the villains, even the wildlife (my theater took special note when Superman saved a squirrel from being crushed). Snyder’s Superman was part of an entire Metropolis 9/11 of horrible collateral damage disaster porn. Gunn’s Superman works hard to make sure the giant kaiju monster, when teetering over, doesn’t fall on any building to protect the people inside. This is also a Superman that feels compelled to be a hero, to do better with his super gifts, and to keep trying even when he fails, that there can be dignity in losing a fight but continuing on because you know that fight is worth it. The depiction of Superman/Clark makes him feel much more a character worth closer examination. He’s not a detached god feeling above these petty mortals always needing saving. The real super power is his empathy and desire to help others, and that may sound corny, but Superman is too, and that’s completely fine in a world that would be better if we had more Supermans and fewer wannabe super villains.

The big question for me was whether Gunn could adapt his cheeky, irony-rich goofball sensibilities from the Guardians movies and make a Superman movie that was earnest and restrained. He has, and let this be a lesson that Gunn does not disappoint when it comes to superhero projects. There are still unmistakable elements of Gunn’s humor and style, like the ironic distance from action serving as an extended joke while characters discuss an unrelated topic, the bouncy and specific needle-drops that cue extended fight or action sequences, and of course the quippy sense of humor. I don’t agree with some of the early reviews I’ve come across that accuse Gunn of undercutting his drama with too many jokes. That is exactly why I was afraid that Gunn would be too insecure with straight drama and earnestness that he would have to rely upon an awkwardly squeezed-in ironic joke to, in his mind, balance the tone. There are jokes, some of them wild and unexpected, but this is most certainly not a movie in the same tonal space as anything Gunn has done before either as a director or a screenwriter. I did not feel that the comedy ever undercut the stakes or the sincerity of the scenes and the movie as a whole. Gunn has shown he can re-calibrate his style and comedic voice while at the same time still making things his own without copious slow-motion. The action is refreshingly staged to be immersive, with few cuts and wide camera swings in order to present everything on the screen in an easily oriented field of vision.

Corenswet (Pearl, Twisters) has some big tights to fill, as I would argue while there have been iffy-to-bad Superman movies there hasn’t been a bad Superman. Obviously the one that all others are defined by is Christopher Reeve who was the greatest special effect the original movie had (I know the flying sequences were groundbreaking for their time, but they play out so cheesy and dated, complete with sudden Margot Kidder poetic resuscitation). Watching him switch from suave hero to clumsy Earthling in a split-second was the best. Corenswet certainly looks the part, clean-cut All-American looks, even though he’s British. He really channels the character’s big heart with his struggle to be accepted, by the public, by the media, by Lois, by even his enemies. He’s got the presence to fill out that suit but the emphasis is not on the contours of his abs but on the unfailing dedication and goodness of a character trying to do right. He won me over early, and it doesn’t hurt hat he has terrific chemistry with Brosnahan, who has been readying herself for this part for years with The Fabulous Mrs. Maisel. She’s great too. Hoult (Nosferatu) channels his smarm perfectly as a very punchable Lex who might make you think about a certain DOGE-master and his team of flunkies wreaking havoc on the rest of the country through unchecked hubris. I loved his pettiness and thinly-veiled vanity, like during an approaching apocalyptic cataclysm and he says to screw the people of Metropolis. “They chose him, let them suffer.” It sounds a lot like, “Your state voted against me, so you won’t get immediate emergency assistance.” You will cheer hard for Lex’s defeat, even more so when his plan involves literal extra-judicial forever confinement.

Corenswet (Pearl, Twisters) has some big tights to fill, as I would argue while there have been iffy-to-bad Superman movies there hasn’t been a bad Superman. Obviously the one that all others are defined by is Christopher Reeve who was the greatest special effect the original movie had (I know the flying sequences were groundbreaking for their time, but they play out so cheesy and dated, complete with sudden Margot Kidder poetic resuscitation). Watching him switch from suave hero to clumsy Earthling in a split-second was the best. Corenswet certainly looks the part, clean-cut All-American looks, even though he’s British. He really channels the character’s big heart with his struggle to be accepted, by the public, by the media, by Lois, by even his enemies. He’s got the presence to fill out that suit but the emphasis is not on the contours of his abs but on the unfailing dedication and goodness of a character trying to do right. He won me over early, and it doesn’t hurt hat he has terrific chemistry with Brosnahan, who has been readying herself for this part for years with The Fabulous Mrs. Maisel. She’s great too. Hoult (Nosferatu) channels his smarm perfectly as a very punchable Lex who might make you think about a certain DOGE-master and his team of flunkies wreaking havoc on the rest of the country through unchecked hubris. I loved his pettiness and thinly-veiled vanity, like during an approaching apocalyptic cataclysm and he says to screw the people of Metropolis. “They chose him, let them suffer.” It sounds a lot like, “Your state voted against me, so you won’t get immediate emergency assistance.” You will cheer hard for Lex’s defeat, even more so when his plan involves literal extra-judicial forever confinement.

However, the real brreak-out star of the movie will most certainly be Krypto, the adorably jumpy super dog. Every time this pooch makes an appearance it is welcomed and he’s utilized as more than just easy comic relief. I expect a sharp uptick in the number of good boys named “Krypto” afterwards.

James Gunn has alleviated all of my fears about him tackling the Man of Steel, and he’s created a Superman that soars above the superhero field. It’s so vibrant and funny and accessible to anyone regardless of their prior feelings or understanding of Superman. It’s also a clear-cut example of what a Superman movie can and should be, sincere and bright and, yes, a little bit corny too. We need this character, and we especially need film artists that know how to craft engaging stories with this character who’s existed for almost 90 years. There’s an inherent lasting power to Superman, and it’s his sheer goodness as an outsider, a feared alien, who has all the powers in the world but just wants to help others. Many have long viewed Superman as boring, a Boy Scout in a world that has grown too morally murky to maintain such a morally unwavering figure of truth, justice, and the American way (what does that last part even mean any more in the bleak environment of 2025?). Gunn has shown us how necessary the character can be, a balm to our troubled times, and the reality that do-gooder figures can be inspirational and aspirational no matter the circumstances. He’s made a Superman movie with an intriguing, lived-in world, one that I now believe can easily support a fuller universe of stories and side characters. He’s also made what I consider the best Superman movie to exist yet (apologies to the nostalgia of the fans of the Richard Donner/Christopher Reeve originals). I have some minor quibbles, like how Lois fades into the background for the second half, but they are only quibbles. This movie was exactly what I needed. I’m sure there are millions of others yearning for the same. Superman is proof that the DC film universe might actually have the perfect person in charge of charting their cross-franchise courses. Kneel before Gunn.

James Gunn has alleviated all of my fears about him tackling the Man of Steel, and he’s created a Superman that soars above the superhero field. It’s so vibrant and funny and accessible to anyone regardless of their prior feelings or understanding of Superman. It’s also a clear-cut example of what a Superman movie can and should be, sincere and bright and, yes, a little bit corny too. We need this character, and we especially need film artists that know how to craft engaging stories with this character who’s existed for almost 90 years. There’s an inherent lasting power to Superman, and it’s his sheer goodness as an outsider, a feared alien, who has all the powers in the world but just wants to help others. Many have long viewed Superman as boring, a Boy Scout in a world that has grown too morally murky to maintain such a morally unwavering figure of truth, justice, and the American way (what does that last part even mean any more in the bleak environment of 2025?). Gunn has shown us how necessary the character can be, a balm to our troubled times, and the reality that do-gooder figures can be inspirational and aspirational no matter the circumstances. He’s made a Superman movie with an intriguing, lived-in world, one that I now believe can easily support a fuller universe of stories and side characters. He’s also made what I consider the best Superman movie to exist yet (apologies to the nostalgia of the fans of the Richard Donner/Christopher Reeve originals). I have some minor quibbles, like how Lois fades into the background for the second half, but they are only quibbles. This movie was exactly what I needed. I’m sure there are millions of others yearning for the same. Superman is proof that the DC film universe might actually have the perfect person in charge of charting their cross-franchise courses. Kneel before Gunn.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Joker: Folie à Deux (2024)

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think actually work as musicals.

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think actually work as musicals.

Joker 2, which I will be referring to it as for the duration of this review mostly because I don’t want to type out Folie a Deux, and not due to some explicit dislike of the French, is a fascinating misfire that comes across as downright disdainful of its audience, its studio, and its very existence. The last time I felt this way from a sequel was 2021’s Matrix Resurrections, another fitfully contemptuous movie that was alienating and self-erasing and also from Warner Brothers. The first Joker movie in 2019 was a surprise hit, grossing over a billion dollars, which meant that the studio wasn’t going to sit idly by and not force a sequel for a movie clearly intended to be one complete movie. While the first movie cost a modest $50 million, the sequel cost close to $200 million, with big pay days for Joaquin Phoenix, Lady Gaga, and co-writer/director Todd Phillips, who I have to remind you, dear reader, was actually nominated for a Best Director Oscar in 2019. Having gotten their paydays, it feels like Phillips and his collaborators have set out to scorch all available earth, going so far as to even insult fans of the earlier movie. Add the bizarre musical factor, and I don’t know how else to describe Joker 2 but as an alienating and miserable protracted exercise in self-immolating artistic hubris. It’s so rare to see this level of artistic clout used to proverbially stick a finger in the eye of every fan and studio exec who might have hoped there could be something of value here.

Let’s tackle the plot first, as we pick up months after the events of the 2019 film where lowly Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) is being tried for the murders he committed, most famously on a TV talk show where he debuted his stand-up comedian persona as Joker in full regalia. There’s an (un)healthy contingent of the rabble that idolize Arthur, finding the Joker to be some kind of mythic hero of class-conscious revolution, pointing out how society is failing all the little guys getting crushed by the rich and powerful and privileged, like that dead Wayne family. One of those fans is Lee (Gaga), a.k.a. Harleen Quinzel, a disturbed young woman obsessed with getting closer to Arthur, and he is extremely appreciative of the fawning attention. The defense case hinges upon whether or not Arthur was acting on his own accord or had a psychotic break, disassociating as “Joker,” and thus cannot be held accountable for the murders. Except it seems “Joker” is all the people of Gotham want to talk about, whether it’s the media or the public, and what about poor lonely Arthur?

Let’s tackle the plot first, as we pick up months after the events of the 2019 film where lowly Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) is being tried for the murders he committed, most famously on a TV talk show where he debuted his stand-up comedian persona as Joker in full regalia. There’s an (un)healthy contingent of the rabble that idolize Arthur, finding the Joker to be some kind of mythic hero of class-conscious revolution, pointing out how society is failing all the little guys getting crushed by the rich and powerful and privileged, like that dead Wayne family. One of those fans is Lee (Gaga), a.k.a. Harleen Quinzel, a disturbed young woman obsessed with getting closer to Arthur, and he is extremely appreciative of the fawning attention. The defense case hinges upon whether or not Arthur was acting on his own accord or had a psychotic break, disassociating as “Joker,” and thus cannot be held accountable for the murders. Except it seems “Joker” is all the people of Gotham want to talk about, whether it’s the media or the public, and what about poor lonely Arthur?

If I had to fathom a larger thematic point, it feels like Phillips is trying to put our media ecosphere and comics fandom into judgement. He’s pointing to his movie and saying, “You wouldn’t have cared nearly as much about this project had it just been some other spooky, disturbed man losing his sanity and lashing out. You only care because he would eventually become the notorious Batman villain or lore, and that’s why you’re back.” Well, to answer succinctly, of course. When your movie’s conceptual conceit is all about providing a gritty back-story for a famous supervillain, don’t be surprised when there’s more attention and interest. This would be the same if Phillips had made a searing drama about teenage nihilism and easy access to guns and then called it Dylan Klebold: The Movie (one half of the Columbine killers, if you forgot). Stripping back layers to provide setup for a famous killer will always generate more interest than if it was some fictional nobody. It’s an accessible starting point for a viewer and there’s an innate intrigue in trying to answer the tantalizing puzzle of how terrible people got to be so terrible.

I found the 2019 movie to be a mostly interesting experiment without too much to say with its larger social commentary. It felt like Phillips relied a bit too heavily on that assumed familiarity with the character to fill in the missing gaps of his storytelling. It was a proof of concept for that proved successful beyond measure (a billion dollars, 11 Oscar nominations, including THREE for Phillips). This time, Phillips is taking even less subtlety with his blowtorch as he actively annihilates whatever audiences may have enjoyed or appreciated in the first movie.

And in order to fully appreciate the scope of this movie’s active distaste for its own existence, I’ll be treading into some major spoilers, so jump forward a paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled, dear reader. The conclusion of this sequel is a miserable succession of hits that degrades Arthur. At the conclusion of the 2019 original, at least you could say he was becoming a more realized version of what he wanted to be, albeit a disturbed murderer, but one who became the face of a revolution and gained a legion of adoring followers that he desperately craved. At the end of Joker 2, Arthur pathetically admits in his trial there is no alternate Joker persona and that he’s just a sad loser. Then Lee admits that she was only ever interested in “Joker” and wants nothing to do with Arthur the sad loser. And then upon returning to prison, another inmate confronts Arthur, apparently feeling personally betrayed for whatever reason. This irate prisoner stabs Arthur to death and then laughs in a corner, slicing a smile into the sides of his mouth, Heath Ledger-style. The movie literally ends with Arthur laying in a pool of his own blood, staring dead-eyed into the camera, with Phillips metaphorically painting emphatically at his corpse and defiantly saying, “Look, he’s not even the Joker now! Do you still care? Do you?” These movies were designed to be the untold history of the man who would be Joker, and they now have ended up being four hours about the guy whose idea maybe inspired a criminal lunatic to improve upon what he felt was another guy’s brand. What’s even the point? We followed two movies about the guy who isn’t the Joker? Seems pretty definitive there won’t be a third Arthur Fleck movie, as there’s nothing left for Phillips and his anarchic collaborators to demolish to smithereens.

And in order to fully appreciate the scope of this movie’s active distaste for its own existence, I’ll be treading into some major spoilers, so jump forward a paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled, dear reader. The conclusion of this sequel is a miserable succession of hits that degrades Arthur. At the conclusion of the 2019 original, at least you could say he was becoming a more realized version of what he wanted to be, albeit a disturbed murderer, but one who became the face of a revolution and gained a legion of adoring followers that he desperately craved. At the end of Joker 2, Arthur pathetically admits in his trial there is no alternate Joker persona and that he’s just a sad loser. Then Lee admits that she was only ever interested in “Joker” and wants nothing to do with Arthur the sad loser. And then upon returning to prison, another inmate confronts Arthur, apparently feeling personally betrayed for whatever reason. This irate prisoner stabs Arthur to death and then laughs in a corner, slicing a smile into the sides of his mouth, Heath Ledger-style. The movie literally ends with Arthur laying in a pool of his own blood, staring dead-eyed into the camera, with Phillips metaphorically painting emphatically at his corpse and defiantly saying, “Look, he’s not even the Joker now! Do you still care? Do you?” These movies were designed to be the untold history of the man who would be Joker, and they now have ended up being four hours about the guy whose idea maybe inspired a criminal lunatic to improve upon what he felt was another guy’s brand. What’s even the point? We followed two movies about the guy who isn’t the Joker? Seems pretty definitive there won’t be a third Arthur Fleck movie, as there’s nothing left for Phillips and his anarchic collaborators to demolish to smithereens.

When I heard that Joker 2 was going to be a musical, I actually got a little excited, as it felt like Phillips was going to try something very different. Now the curse of many modern movie musicals is trying to come up with an excuse for why the world is exploding in song and dance, like 2002’s Chicago implying it’s all in Roxy’s vivid imagination. Joker 2 takes a similar approach, conveying that when Arthur is breaking out into song that it’s a mental escape for him, that it’s not actually happening in his literal reality. Except… why are there sequences outside Arthur’s point of view where other characters are breaking into song, notably Lee? Is this perhaps a transference of Arthur’s perspective, like he’s imagining them on the outside joining him in tandem? The concept fits with his desperate desire to forge meaningful human connections with people that see him for who he is, and having another character harmonize with him provides a fantasy of validation. Except… there’s no meaningful personal connection between Arthur and the allure of movie musicals. It’s not like he or his domineering mother, the same woman he murdered if you recall, were lifelong fans of musicals and their magical possibilities. It’s not like 2001’s Dancer in the Dark where our lonely protagonist dreamed of being in a movie musical as an escape from her depressing life of exploitation and poverty. It just happens, and you’re listening to Phoenix’s off-putting, gravelly voice straining to recreate classics like “For Once in My Life” and “When You’re Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You).” It’s also a criminal waste of a perfectly game Gaga.

Phillips’ staging of his musical numbers are so lifelessly devoid of energy and imagination. Most of our musical numbers are merely in the same setting without any changes besides now one, or occasionally two, characters are singing. There’s one number that becomes a dance atop a roof, and several duets that appear like a hammy Sonny and Cher 1970s variety TV show, and that’s all you’re getting folks in the realm of visual escapism and choreography. In retrospect, it feels like the musical aspect of the sequel might have been a manner to pad it to feature-length, adding 16 performances and over 40 minutes of singing old standards. There’s a good deal of repetition with this sequel, as much of the plot is restating the events of the first film; that’s essentially what the courtroom drama facilitates as it trots out all the previous characters to recap their roles and point an accusatory finger back at Arthur.

Phillips’ staging of his musical numbers are so lifelessly devoid of energy and imagination. Most of our musical numbers are merely in the same setting without any changes besides now one, or occasionally two, characters are singing. There’s one number that becomes a dance atop a roof, and several duets that appear like a hammy Sonny and Cher 1970s variety TV show, and that’s all you’re getting folks in the realm of visual escapism and choreography. In retrospect, it feels like the musical aspect of the sequel might have been a manner to pad it to feature-length, adding 16 performances and over 40 minutes of singing old standards. There’s a good deal of repetition with this sequel, as much of the plot is restating the events of the first film; that’s essentially what the courtroom drama facilitates as it trots out all the previous characters to recap their roles and point an accusatory finger back at Arthur.

There is one lone outstanding scene in Joker 2, and it happens to be when Arthur, in full Joker makeup, is cross-examining his old clown entertainer work buddy, Gary Puddles (Leigh Gill). Arthur admonishes Gary, saying he spared him, and Gary painfully articulates how hellish his life has been as witness to Arthur’s killing, how little he sleeps, how it torments him and makes him so afraid. For a brief moment, this character shares his vulnerability and the lingering trauma that Arthur has inflicted, and it appears like Arthur is wounded by this realization, until he settles back into the persona he’s trying to put forward, the “face” for his defense, and goes back to ridiculing Gary’s name and turning the cross-examination into an awkward standup session. It’s a palpable moment that feels raw and surprising and empathetic in a way the rest of the movie fails to.

Is there anything else to celebrate with Joker 2’s troubled existence? The cinematography by Lawrence Sher can be strikingly beautiful, especially with certain shot compositions and lighting contrasts. It makes it all the more confounding when almost all the musical numbers lack visual panache. The Oscar-winning composer returns and while still atmospheric and murky the score is also far less memorable and fades too often into the background, like too many of the technical elements. Joker 2 has plenty of talented people involved in front of and behind the camera, but to what end? What are all their troubles adding up to? It practically feels like a very expensive practical joke, on the audience, on the studio, and that is genuinely fascinating. However, it doesn’t make the end product any better, and the film’s transparent contempt sours every minute of action. Even if you were a super fan of Joker or morbidly curious, steer clear of Folie a Deux, a folly on all of us.

Nate’s Grade: D

Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom (2023)

Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom is he last of the Zack Snyder-then-not-Snyder-verse DCU movies, and with that the ten years of mostly middling super hero heroics comes to an end not with a bang but with a whimper. I was a fan of 2018’s original Aquaman thanks to the self-aware craziness and visual decadence from its wily director, James Wan (Malignant). This is still the major appeal of the franchise, a universe that feels pulled from a child’s imagination and recreated in loving splendor on the big screen. The problem with this tone is that it’s a delicate balance between silly fun and silly nonsense. The goofy charm of these movies is still alive and well as they open up an even bigger undersea world of lore (Martin Short as a fish lord!), but this time it feels like a movie that is making it up as it goes, and all that “and this happens next” storytelling begins to feel like a monstrous CGI mess needing to be tamed. This might have something to do with the fact that Wan finished filming the movie over two years ago and it’s endured several re-shoots, including featuring two different Batman actor cameos at different points, to now bring to a close a decade of interconnected movies that are going to be blinked out of larger continuity in 2025 (excluding Margot Robbie’s Harley Quinn, I guess). Lost Kingdom has plenty of enjoyably weird undersea nightmare creatures, a specialty of Wan given his horror roots, but the ultimate villain spends most of his time sitting on a throne in wait and is laughably dismissed so easily in the climax. The whole evil magic trident that corrupts from its evil influence has a very Lord Sauron ring to it. I give the movie points for transforming into a buddy movie between Arthur Curry (Jason Momoa) and his brother Orm (Patrick Wilson) halfway through. The jail break sequence is fun and different, and their bickering dynamic makes for winning comedy. However, the drama feels too overworked, with holdovers from the first film (Black Manta, Amber Heard’s unremarkable love interest) repeating their same beats with robotic dedication. The opening reveal of Arthur being a new dad and it cramping his macho-cool style made he fear we were headed for Shrek 4 territory, where the new dad needs one more adventure to realize the importance of family, etc. Because even when you’re riding a mechanical shark, fighting alongside the crab people, and tunneling through worm prisons, it’s all about recognizing the importance of family, kids (the real undersea treasure after all). I defy anyone not to laugh at the literal concluding speech and its enigmatic “sure, fine, whatever”-energy. As a mere movie, Lost Kingdom is silly escapist entertainment that could enchant a few with lowered expectations, and as the final entry point in a universe of super heroes, it’s a fitting nonsensical end.

Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom is he last of the Zack Snyder-then-not-Snyder-verse DCU movies, and with that the ten years of mostly middling super hero heroics comes to an end not with a bang but with a whimper. I was a fan of 2018’s original Aquaman thanks to the self-aware craziness and visual decadence from its wily director, James Wan (Malignant). This is still the major appeal of the franchise, a universe that feels pulled from a child’s imagination and recreated in loving splendor on the big screen. The problem with this tone is that it’s a delicate balance between silly fun and silly nonsense. The goofy charm of these movies is still alive and well as they open up an even bigger undersea world of lore (Martin Short as a fish lord!), but this time it feels like a movie that is making it up as it goes, and all that “and this happens next” storytelling begins to feel like a monstrous CGI mess needing to be tamed. This might have something to do with the fact that Wan finished filming the movie over two years ago and it’s endured several re-shoots, including featuring two different Batman actor cameos at different points, to now bring to a close a decade of interconnected movies that are going to be blinked out of larger continuity in 2025 (excluding Margot Robbie’s Harley Quinn, I guess). Lost Kingdom has plenty of enjoyably weird undersea nightmare creatures, a specialty of Wan given his horror roots, but the ultimate villain spends most of his time sitting on a throne in wait and is laughably dismissed so easily in the climax. The whole evil magic trident that corrupts from its evil influence has a very Lord Sauron ring to it. I give the movie points for transforming into a buddy movie between Arthur Curry (Jason Momoa) and his brother Orm (Patrick Wilson) halfway through. The jail break sequence is fun and different, and their bickering dynamic makes for winning comedy. However, the drama feels too overworked, with holdovers from the first film (Black Manta, Amber Heard’s unremarkable love interest) repeating their same beats with robotic dedication. The opening reveal of Arthur being a new dad and it cramping his macho-cool style made he fear we were headed for Shrek 4 territory, where the new dad needs one more adventure to realize the importance of family, etc. Because even when you’re riding a mechanical shark, fighting alongside the crab people, and tunneling through worm prisons, it’s all about recognizing the importance of family, kids (the real undersea treasure after all). I defy anyone not to laugh at the literal concluding speech and its enigmatic “sure, fine, whatever”-energy. As a mere movie, Lost Kingdom is silly escapist entertainment that could enchant a few with lowered expectations, and as the final entry point in a universe of super heroes, it’s a fitting nonsensical end.

Nate’s Grade: C

The Flash (2023)/ Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (2023)

Released within two weeks of one another, two big summer movies take the concept of a multiverse, now becoming the norm in comic book cinema, and explore the imaginative possibilities and wish-fulfillment that it proposes, but only one of them does it well. Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is the sequel to the Oscar-winning 2018 revolutionary animated film, and it’s a glorious and thrilling and visually sumptuous experience, whereas DC’s much-hyped and much-troubled movie The Flash feels like a deflated project running in place and coming apart. Let this be a lesson to any studio executive, that multiverses are harder than they look.

Barry Allen (Ezra Miller) has the ability to travel at fantastic speeds as his superhero alter ego, The Flash. He’s tired of being the Justice League’s errand boy and still fighting to prove his father is innocent of the crime of killing Barry’s mother. Then Barry discovers he can run fast enough to actually travel back in time, so he returns with the intention of trying to save his mother. Except now he’s an extra Flash and has to train his alternate self (also Miller) how to control his powers. In this different timeline, there is no Justice League to combat General Zod (Michael Shannon, so thoroughly bored) from destroying the planet for Kryptonians.

This is the first big screen solo outing for The Flash, and after none other than Tom Cruise, Stephen King, and James Gunn calling it one of the best superhero movies of all time, it’s hard to square how trifling and mediocre so much plays out as an example of a creative enterprise being pulled in too many directions. Miller was cast as the speedster almost ten years ago, and this tale has gone through so much tortured development, leaping through numerous filmmakers and writers, that its purpose has now gone from being a pillar of the expanding DC cinematic universe began with Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel in 2013 to becoming the Snyderverse’s death knell. The premise of traveling back in time is meant for Barry to learn important lessons about grief and responsibility and the limits of his powers, but it’s also intended as the reboot option for the future of these cross-connected comic franchises. It allows Gunn, now the co-head of the new way forward for DC movies and TV, to keep what they want (presumably Margot Robbie and Jason Momoa) and ditch the rest (Henry Cavill, Ben Affleck, Black Adam, Shazam, and Zack Snyder’s overall creative influence). So reviewing The Flash as only a movie is inadequate; it’s also a larger ploy by its corporate overlords to reset their comic book universe. In that regard, the quality level of the movie is secondary to its mission of wiping the creative slate clean.

Where the movie works best is with its personal stakes and the strange but appealing chemistry between the two Millers. It’s an easy starting point to understand why Barry does what he does, to save his mother. This provides a sturdy foundation to build a character arc, with Barry coming to terms with accepting his grief rather than trying to eradicate it. That stuff works, and the final talk he has to wrap up this storyline has an emotional pull that none of the other DCU movies have exhibited. Who wouldn’t want one last conversation with a departed loved one, one last opportunity to say how you feel or to even tell them goodbye? This search for closure is a relatable and an effective vehicle for Barry to learn, and it’s through his tutelage of the other Barry that he gets to see beyond himself. The movie is at its best not with all its assorted cameos and goofy action (more on both later) but when it’s a buddy comedy between the two Barrys. The older Barry becomes a mentor to himself and has to teach this inexperienced version how to hone and control his powers as well as their limits. It puts the hyper-charged character into a teaching position where he has to deal with a student just like him (or just him). It serves as a soft re-education for the audience alongside the other Barry without being a full origin story. The impetuous young Barry wanting to have everything, and the elation he feels about his powers, can be fun, but it’s even more fun with the older Barry having to corral his pupil. It also allows the character an interactive checkpoint for his own maturity and mental growth. Miller’s exuberant performances are quite entertaining and never fail to hit the comedy beats.

The problem is that the movie puts so much emphasis on too many things outside of its titular hero. Much was made of bringing back Keaton to reprise his Batman after 30 years. I just wish he came back for a better reason and had legitimate things to add. His role is that of the retired gunslinger being called back into action, and there’s an innate understanding with Barry wanting to go back in time and save his family, but too much of this character’s inclusion feels like a stab at stoking audience nostalgia (the callback lines all made me groan). I highly enjoyed Keaton as Batman and appreciated how weird he could make the billionaire-turned-vigilante, but he’s no more formed here than a hologram. The same thing happens with the inclusion of Super Girl a.k.a. Kara Zor-El (Sasha Callie). In this universe, there is no Superman, so she’s our requisite super-powered alien that Zod is hunting to complete his plans for terraforming Earth. She’s an intriguing character as a tortured refugee who has lingering doubts about whether humanity is worth the sacrifice, but much of her usage is meant only to make us think about Superman. She’s not given material to make her own impression, so she simply becomes the imitation of the familiar, the shadow to the archetype already being left behind. But these character additions aren’t even the worst of the nostalgia nods, as the final climactic sequence involves a collision of worlds that harkens to just about every iteration of the famous DC heroes, resurrecting several with dodgy CGI and uncomfortable implications (spoilers… the inclusion of George Reeves, when he felt so typecast as TV’s Superman that he supposedly killed himself because he thought his acting career was over, can be galling).