Blog Archives

Eddington (2025)

I’ve read more than a few searing indictments about writer/director Ari Aster’s latest film, Eddington, an alienating and self-indulgent movie starring Joaquin Phoenix on the heels of his last alienating and self-indulgent movie starring Phoenix. It’s ostensibly billed as a “COVID-era Western,” and that is true, but it’s much more than that. I can understand anyone’s general hesitation to revisit this acrimonious time, but that’s where the “too early yet too late” criticism of others doesn’t ring true for me. It is about that summer of 2020 and the confusion and anger and anxiety of the time; however, I view Eddington having more to say about our way of life in 2025 than looking back to COVID lockdowns and mask mandates. This is a movie about the way we live now and it’s justifiably upsetting because that’s where the larger culture appears to be at the present: fragmented, contentious, suspicious, and potentially irrevocable.

Eddington is a small-town in the dusty hills of New Mexico, neighboring a Pueblo reservation, and it serves as a tinderbox ready to explode from the tension exacerbated from COVID. Sheriff Joe Cross (Phoenix) has had it up to here with mask mandates and social distancing and the overall attitude of the town’s mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal). Joe decides to run for mayor himself on a platform of common-sense change, but nothing in the summer of 2020 was common.

Eddington is a movie with a lot of tones and a lot of ideas, and much like 2023’s Beau is Afraid, it’s all over the place with mixed results that don’t fully come together for a coherent thesis. However, that doesn’t deny the power to these indefatigable moments that stick with you long after. That’s an aspect of Aster movies: he finds a way to get under your skin, and while you may very well not appreciate the experience because it’s intentionally uncomfortable and probing, it sticks with you and forces you to continue thinking over its ideas and creative choices. It’s art that defiantly refuses to be forgotten. With that being said, one of the stronger aspects of Aster’s movies is his pitch-black sense of comedy that borders on sneering cynicism that can attach itself to everything and everyone. There are a lot of targets in this movie, notably conspiracy-minded individuals who want people to “do their own research,” albeit research ignoring verified and trained professionals with decades of experience and knowledge. There’s a lot of people talking at one another or past one another but not with one another; active listening is sorely missing, as routinely evidenced by the silences that accompany the mentally-ill homeless man in town that nobody wants to actively help because they see him as an uncomfortable and loud nuisance. For me, this is indicative of 2025, with people rapidly talking past one another rather than wanting to be heard.

When Aster is poking fun at the earnestness of the high school and college students protesting against police brutality, I don’t think he’s saying these younger adults are stupid for wanting social change. He’s ribbing how transparently these characters want to earn social cache for being outspoken. It’s what defines the character of Brian, just a normal kid who is so eager to be accepted that he lectures his white family on the tenets of destroying their own white-ness at the dinner table, to their decidedly unenthusiastic response. I don’t feel like Aster is saying these kids are phony or their message is misapplied or ridiculous or without merit. It’s just another example of people using fractious social and political issues as a launching point to air grievances rather than solutions. The protestors, mostly white, will work themselves into a furious verbal lather and then say, “This shouldn’t even be my platform to speak. I don’t deserve to tell you what to do,” and rather than undercutting the message, after a few chuckles, it came across to me like the desperation to connect and belong coming out. They all want to say the right combination of words to be admired, and Brian is still finding out what that might be, and his ultimate character arc proves that it wasn’t about ideological fidelity for him but opportunism. The very advancement of Brian by the end is itself its own indictment on white privilege, but you won’t have a character hyperventilating about it to underline the point. It’s just there for you to deliberate.

Along these lines, there’s a very curious inclusion of a trigger-happy group in the second half of the movie that blends conspiracy fantasy into skewed reality, and it begs further unpacking. I don’t honestly know what Aster is attempting to say, as it seems like such a bizarre inclusion that really upends our own understanding of the way the world works, and maybe that’s the real point. Maybe what Aster is going for is attempting to shake us out of our own comfortable understanding of the universe, to question the permeability of fact and fiction. Maybe we’re supposed to feel as dizzy and confused as the residents of Eddington trying to hold onto their bearings during this chaotic and significant summer of 2020.

I think there’s an interesting rejection of reality on display with Eddington, where characters are trying to square news and compartmentalize themselves from the proximity of this world. Joe Cross repeatedly dismisses the pandemic as something happening “out there.” He says there is no COVID in Eddington. For him, it’s someone else’s problem, which is why following prevailing health guidelines and mandates irks him so. It’s the same when he’s trying to explain his department’s response to the Black Lives Matter protests that summer in response to George Floyd’s heinous murder. To him, these kinds of things don’t happen here, the people of Eddington are excluded from the social upheaval. This is an extension of the “it won’t happen to me” denialism that can tempt any person into deluding ourselves into false security. It’s this kind of rationalization that also made a large-scale health response so burdensome because it asked every citizen to take up the charge regardless of their immediate danger for the benefit of others they will never see. For Joe, the tumult that is ensnaring the rest of the country is outside the walls of Eddington. It’s a recap on a screen and not his reality. Except it is his reality, and the movie becomes an indictment about pretending you are disconnected from larger society. It’s easier to throw up your hands and say, “Not me,” but it’s hard work to acknowledge the troubles of our times and our own engagement and responsibilities. In 2025, this seems even more relevant in our doom-scrolling era of Trump 2.0 where the Real World feels a little less real every ensuing day. It’s all too easy to create that same disassociation and say, “That’s not here,” but like an invisible airborne virus not beholden to boundaries and demarcations, it’s only a matter of time that it finds your doorstep too.

You may assume with its star-studded cast that this will be an ensemble with competing storylines, but it’s really Joe Cross as our lead from start to finish, with the other characters reflections of his stress. I won’t say that most of the name actors are wasted, like Emma Stone as Joe’s troubled wife and Austin Butler as a charismatic conman pushing repressed memory child-trafficking conspiracies, because every person is a reflection over what Joe Cross wants to be and is struggling over. Despite his flaws and some startling character turns, Aster has great empathy for his protagonist, a man holding onto his authority to provide a sense of connectivity he’s missing at home. Our first moment with this man is watching him listen to a YouTube self-help video on dealing with the grief of wanting children when your spouse does not. Right away, we already know there’s a hidden wealth of pain and disappointment here, but again Aster chooses empathy rather than easy villainy, as we learn his wife is struggling with PTSD and depression likely as a result of her own father’s potential molestation. This revelation can serve as a guide for the rest of the characters, that no matter their exterior selves that can demonstrate cruelty and absurdism, deep down many are processing a private pain that is playing out through different and often contentious means of survival. I don’t think Aster condones Joe Cross’ perspective nor his actions in the second half, but I do think he wants us to see Joe Cross as more than just some rube angry with lockdown because he’s selfish.

It’s paradoxical but there are scenes that work so splendidly while the movie as a whole can seem overburdened and far too long. The cinematography by the legendary Darius Khnodji (Seven, City of Lost Children) expertly frames and lights each moment, many of them surprising, intriguing, revealing, or shocking. There can be turns that feel sudden and jarring, that catapult the movie into a different genre entirely, into a Hitchcockian thriller where we know exactly what the reference point is that I won’t spoil, to an all-out action showdown popularized by Westerns. Beyond Aster’s general more-is-more preference, I think he’s dabbling with the different genres to not just goose his movie but to question our associations with those genres and our broader understanding of them. It’s not quite as clean as a straight deconstructionist take on familiar archetypes and tropes. It’s more deconstructing our feelings. Are we all of a sudden in a forgiving mood because the movie presents Joe as a one-man army against powerful forces? It’s all-too easy to get caught up in the rush of tension and satisfying violence and root for Joe, but should we? Is he a hero just because he’s out-manned? Likewise, with the conclusion, do we have pity for these people or contempt? I don’t know, though there isn’t much hope for the future of Eddington, and depressingly perhaps for the rest of us, so maybe all we have are those fleeting moments of awe to hold onto and call our own.

Eddington is an intriguing indictment about our modern culture and the rifts that have only grown into insurmountable chasms since the COVID-19 outbreak. It’s a Western in form pitting the figure of the law against the moneyed establishment, and especially its showdown-at-the-corral climax, but it’s also not. It’s a drama about people in pain looking for answers and connections but finding dead-ends, but it’s also not. It’s an absurdist dark comedy about dumb people making dumb and self-destructive decisions, but it’s also not. The paranoia of our age is leading to a silo-ing of information dissemination, where people are becoming incapable of even agreeing on present reality, where our elected leaders are drowning out the reality they don’t want voters to know with their preferred, self-serving fantasy, and if they just say it long enough, then a vulnerable populace will start to conflate fact and fiction. I don’t know what the solution here is, and I don’t think Aster knows either by the end of Eddington. I can completely understand people not wanting to experience a movie with these kinds of uncomfortable and relevant questions, but if you want to have a closer understanding of how exactly we got here, then Eddington is an artifact of our sad, stupid, and supremely contentious times. Don’t be like Joe and ignore what’s coming until it’s too late.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Bubble (2022)/ Moonfall (2022)

What to do with a comedy that just isn’t that funny? I come to co-writer/director Judd Apatow’s The Bubble with a rhetorical surgeon’s scalpel ready to figure out this conundrum. There are plenty of funny people involved with this Netflix project. Apatow has been an industry unto himself in developing comedic talent going back to his Freaks and Geeks TV days and with such heralded twenty-first century comedies to his credit like The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up. The cast assembled for The Bubble has great comic potential. Even the premise is fun, a group of spoiled actors trying to film a bad sci-fi action movie under the challenges of the COVID-19 quarantine. So what went wrong here and why is The Bubble Apatow’s least engaging and least funny movie to date?

What to do with a comedy that just isn’t that funny? I come to co-writer/director Judd Apatow’s The Bubble with a rhetorical surgeon’s scalpel ready to figure out this conundrum. There are plenty of funny people involved with this Netflix project. Apatow has been an industry unto himself in developing comedic talent going back to his Freaks and Geeks TV days and with such heralded twenty-first century comedies to his credit like The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up. The cast assembled for The Bubble has great comic potential. Even the premise is fun, a group of spoiled actors trying to film a bad sci-fi action movie under the challenges of the COVID-19 quarantine. So what went wrong here and why is The Bubble Apatow’s least engaging and least funny movie to date?

We follow the Hollywood production of Cliff Beasts 6, filming in rural England under the supervision of studio execs trying to keep the secluded production as problem-free as possible under the 2020 COVID outbreak. Karen Gillan (Avengers Endgame) plays Carol Cobb, an actress returning to the franchisee she had once left behind to star in a misguided Oscar bait movie where she, a white woman, was the solution to solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She’s hoping to save her career, while her coworkers are just hoping not to go insane with the forced isolation and new safety protocols during their film shoot.

So let’s circle back to the central question of why The Bubble isn’t funny, and I think I have some theories. First, we can acknowledge comedy is subjective but at the same time also acknowledge that the construction of good comedy can be academically identified and appreciated, that there are tenets that hold and maintain, like setups and payoffs, rules of threes, etc. I think one of the big problems is that nothing is really that surprising throughout the protracted and unfocused duration of The Bubble.

So let’s circle back to the central question of why The Bubble isn’t funny, and I think I have some theories. First, we can acknowledge comedy is subjective but at the same time also acknowledge that the construction of good comedy can be academically identified and appreciated, that there are tenets that hold and maintain, like setups and payoffs, rules of threes, etc. I think one of the big problems is that nothing is really that surprising throughout the protracted and unfocused duration of The Bubble.

The characters are intended to be shallow but are too shallow to even register as distinct comedy types played against one another. There are levels of general buffoonery, but so many of these characters are missing out on a more definite angle or perspective. Take for instance the smug movie star (David Duchovny) who takes it upon himself to rewrite the script. This should be an obvious route where the story comes undone or character actions are inconsistent or that other characters, especially those who had larger roles, become subservient to the star and his ballooning ego. There needs to be distinct differences for the comedy to land and be an indication of his ideas about what he thinks would be an improvement. This doesn’t really happen. Take the recent Oscar winner (Pedro Pascal). He’s not haughty and pompous, thinking himself beneath this kind of genre filmmaking. He’s simply a dumb hedonist who is seeking out pleasure he is denying himself. That’s fine, as at least one character is set up to be more of a wild card to stir trouble. This character spends the entire movie whining and having unfunny fantasies when they should be the one causing havoc and unexpected consequences from their behaviors. What a waste. Every character falls into this nebulous underwritten area without being distinct enough to be considered stock and ultimately useful for comparisons and generating comedic conflicts.

Another lack of surprise is how every character is exactly how they are presented, so with no points of change it all gets very redundant. If this was going to be the case, Apatow needed to be far more exacting with his satirical barbs. If he wants to really send up the industry and self-absorbed actors, we need something akin to 2008’s Tropic Thunder, which, by the way, had very distinct character differences it used for maximum comedy. This movie feels more like an extension of the privileged world populated by the bourgeoisie characters from 2012’s This is 40, a marked misstep for Apatow and his idea of recognizable midlife struggles (“Oh no, we’ll have to move from our ridiculously large house to… just a very large house!”). It’s the same pitiable rich people whining about their lives while they quarantine in luxury. Watching montage after montage of them being bored in their private hotel suites is not funny. It doesn’t even work as a criticism of the characters on display. They aren’t doing anything out there or particularly telling, they’re just being bored, and just watching bored people is boring.

The moviemaking process and the film-within-a-film itself is also shockingly unfunny. Apatow has worked in Hollywood for decades, so I was expecting harder-hitting satire of the moviemaking industry and the way that films are continuously compromised. As another example of shallow character writing, take the director (Fred Armison), a Sundance award-winning indie artist tackling their first studio project. The expected route would be to start with this character having big ideas about a grand artistic vision, taking real chances, and trying to do something different and compelling within the realm of giant dinosaur action movies, and then little by little, they have to compromise and delete this grand vision, taking studio notes, limitations from the actors, and bad luck. This would provide a foil for every bad item complicating the production, the artist struggling to watch their dream die piece-by-piece. This doesn’t happen and the director’s indie background is never utilized as a contrast for comedy.

The moviemaking process and the film-within-a-film itself is also shockingly unfunny. Apatow has worked in Hollywood for decades, so I was expecting harder-hitting satire of the moviemaking industry and the way that films are continuously compromised. As another example of shallow character writing, take the director (Fred Armison), a Sundance award-winning indie artist tackling their first studio project. The expected route would be to start with this character having big ideas about a grand artistic vision, taking real chances, and trying to do something different and compelling within the realm of giant dinosaur action movies, and then little by little, they have to compromise and delete this grand vision, taking studio notes, limitations from the actors, and bad luck. This would provide a foil for every bad item complicating the production, the artist struggling to watch their dream die piece-by-piece. This doesn’t happen and the director’s indie background is never utilized as a contrast for comedy.

Apatow plays the same trick over and over with the film-within-a-film. It will be a dramatic sequence and then cut to the actors running on a treadmill or swinging behind a green screen, the same undercutting gag on repeat. It’s not funny and, frankly, gets tiresome. The ridiculous nature of blockbuster filmmaking should be ripe for satire (again, Tropic Thunder did it) but Apatow never pushes too hard, settling on the same soft-pedaled jokes on simple characters. Pascal is left to practice funny accents, but none of what they say within the movies is funny-bad; it’s just tin-eared dialogue that is merely bad only. The only segment that genuinely had me laughing was when the young actress (Iris Apatow) teaches a raptor how to do the latest TikTok dance. This is the only moment that feels biting on the out-of-touch desperation of modern moviemaking to chase and incorporate vaporous youth trends to remain hip. The Hollywood film gone awry should feel like a mess, it should be getting progressively worse or more out of control or at least something so outlandish it separates itself from its targets. I suppose shooting the CGI genitals off dinosaurs is something you don’t see every day but it too gets old fast.

Fortunately, these actors can still be charming even with lesser material, but you’ll simply walk away feeling enormous sympathy for them. Everyone is trying to do so much with so very little, and it can get painful at points, like Pascal’s character clinging to an amorphous evolution of an accent. There are very funny people here. Keegan Michael-Key is very funny, but he gets nothing here, especially with a ripe subplot where he might be starting a self-help cult. Maria Bakalova is very funny, and was even nominated for an Oscar, a rarity for a comedian, but she gets nothing here, being a horny hotel worker. Gillan is very funny, but she too gets nothing here as a slumming actress desperate to rehabilitate her career. It’s remarkable considering she’s the main character but really just an insecure straight man role. The main character needed to be Gavin (Peter Serafinowicz), the producer on location doing his best to herd all these spoiled and irresponsible people into getting this movie made and on time. You want to focus on the character with the most chaos to try and control, and that’s him. It just feels criminal that a cast this good, with fun supporting players like Samson Kayo (Our Flag Means Death) and Harry Trevaldwyn (Ten Percent) to round out the more famous faces.

Fortunately, these actors can still be charming even with lesser material, but you’ll simply walk away feeling enormous sympathy for them. Everyone is trying to do so much with so very little, and it can get painful at points, like Pascal’s character clinging to an amorphous evolution of an accent. There are very funny people here. Keegan Michael-Key is very funny, but he gets nothing here, especially with a ripe subplot where he might be starting a self-help cult. Maria Bakalova is very funny, and was even nominated for an Oscar, a rarity for a comedian, but she gets nothing here, being a horny hotel worker. Gillan is very funny, but she too gets nothing here as a slumming actress desperate to rehabilitate her career. It’s remarkable considering she’s the main character but really just an insecure straight man role. The main character needed to be Gavin (Peter Serafinowicz), the producer on location doing his best to herd all these spoiled and irresponsible people into getting this movie made and on time. You want to focus on the character with the most chaos to try and control, and that’s him. It just feels criminal that a cast this good, with fun supporting players like Samson Kayo (Our Flag Means Death) and Harry Trevaldwyn (Ten Percent) to round out the more famous faces.

This also made me think to reflect on the recent release of Moonfall, which looks like the big, schlocky sci-fi disaster movie that Judd Apatow would be satirizing with The Bubble. It’s a Roland Emmerich disaster movie where he does exactly what Roland Emmerich does best: expansive scenes of cataclysmic destruction on the biggest scale possible. It was believed by industry watchers that Moonfall would be the kind of epic that people would go back to the movies to experience, watching the scale of destruction on the biggest screen and cheering along. It didn’t work out that way and Moonfall reportedly will lose over a hundred million dollars for its investors. It seemed like a smart bet as disaster movies have performed well for Emmerich, like 2012 and The Day After Tomorrow. In times of struggle, human beings enjoy fantasies about surviving fantastic odds, or at least that was the established way of thinking. After two years of life during COVID-19, maybe our idea of sci-fi escapism isn’t quite what it used to be.

I watched Moonfall with general indifference. It felt like a mediocre hodgepodge of other Emmerich disaster movies and veered into campy nonsense at many points. It’s the kind of movie that demands you shut off your brain and just go along with the scientific gobbledygook, especially once the moon begins making Earth’s gravity go all haywire. At that point the movie becomes an inconsistent video game with its liberal use of physics. It doesn’t seem like it matters, but watching characters do Super Mario Brother-level jumps has a fun appeal as well as being impossibly goofy. One character says, “The moon can’t do these things,” and another character waves away that pertinent thought and says, almost directly to the audience, “Yeah, but this isn’t a normal moon, so forget everything.” The special effects are also quite hit or miss. Plenty of the larger effects are quite awe-inspiring and suitably terrifying in depicting an awesome reality, and then others look like they didn’t quite have enough money when it came time to render. Some of the CGI reminded me of moments from 2008’s Torque, where the high-speed backgrounds resembled badly composited video game texture blurs. If your movie is going to exist primarily in a junk food realm, then you need to either have as minimal distractions as possible to rip you from the believability of this world, or you simply need to veer into it and accept that the instability and chaos will be part of the general appeal. Provide the goods, and Moonfall just doesn’t.

The movie also takes an inordinate amount of time to get back to space after a prologue, almost halfway through its two hours. This first half stalls with setting up so many characters to follow that you simply won’t care about. I didn’t care what happened to anyone back on Earth. When the rednecks found our party (again!) in a petty car chase, I literally laughed out loud. The alien/moon mythology is also convoluted and vague enough to simply apply a good versus evil designation for technology, and the big sacrifice doesn’t feel so big when you find that character to be annoying for the duration of their grating screen time. It’s another movie tipping you off about a possible linked sequel and one that appears more appetizing than the film we just witnessed (just like Emmerich’s 2016 Independence Day sequel). In short, Moonfall is a bit of a mess, a mess I can imagine others enjoying and laughing with, but definitely one of the lower outputs in Emmerich’s long career of destroying global landmarks and formerly pristine vistas.

The movie also takes an inordinate amount of time to get back to space after a prologue, almost halfway through its two hours. This first half stalls with setting up so many characters to follow that you simply won’t care about. I didn’t care what happened to anyone back on Earth. When the rednecks found our party (again!) in a petty car chase, I literally laughed out loud. The alien/moon mythology is also convoluted and vague enough to simply apply a good versus evil designation for technology, and the big sacrifice doesn’t feel so big when you find that character to be annoying for the duration of their grating screen time. It’s another movie tipping you off about a possible linked sequel and one that appears more appetizing than the film we just witnessed (just like Emmerich’s 2016 Independence Day sequel). In short, Moonfall is a bit of a mess, a mess I can imagine others enjoying and laughing with, but definitely one of the lower outputs in Emmerich’s long career of destroying global landmarks and formerly pristine vistas.

I found Moonfall and The Bubble to both be poor examples of what Hollywood thinks audiences will desire as escapism in the wake of COVID-19 disrupting routines and lives. Each of the movies is disappointing because it doesn’t fulfill what it promises. The Bubble has a bunch of combustible characters in a combustible scenario and squanders its time with weak satirical gags and lazy characterization. Moonfall wants to be the big, fun epic of Emmerich’s past, but it takes its sweet indulgent time with uninteresting characters, convoluted and underwritten lore, and a plot that would have been more entertaining had it better embraced the absurdity of its implications. You may likely have an enjoyable time watching either movie, and they’re almost the same length too, but I found both to be middling examples of Hollywood’s attempt to try and give the people what they think they want and missing the entertainment mark.

Nate’s Grades:

The Bubble: C

Moonfall: C+

Locked Down (2021)

I’m already starting to dread the inevitable onslaught of movies and fictional narratives tackling the COVID crisis, and I don’t know if that’s ever going to be truly inviting for me. After the near year of pandemic fatigue, I can’t see myself wanting to relive the experience through my media. Naturally, this is partially because of how fresh everything is. Years down the road I may hold a different opinion and find COVID-19 stories more engaging. I’m sure there will be worthy ones to explore with the best storytellers that movies and television can afford. Right now, I’m not looking forward to the rom-coms about couples being forced together, or forced apart, and I’m not looking forward to the zombie movies that seem all too obvious in commentary. It is with this context that I watched the new 2021 movie Locked Down with wary curiosity. It was filmed during the quarantine in London over 18 days. It stars big actors, has a director and writer who have worked on highly esteemed projects, and it’s the first big project to feature the pandemic while we’re still in the middle of a worldwide pandemic. It has temporary notoriety but is it any good?

I’m already starting to dread the inevitable onslaught of movies and fictional narratives tackling the COVID crisis, and I don’t know if that’s ever going to be truly inviting for me. After the near year of pandemic fatigue, I can’t see myself wanting to relive the experience through my media. Naturally, this is partially because of how fresh everything is. Years down the road I may hold a different opinion and find COVID-19 stories more engaging. I’m sure there will be worthy ones to explore with the best storytellers that movies and television can afford. Right now, I’m not looking forward to the rom-coms about couples being forced together, or forced apart, and I’m not looking forward to the zombie movies that seem all too obvious in commentary. It is with this context that I watched the new 2021 movie Locked Down with wary curiosity. It was filmed during the quarantine in London over 18 days. It stars big actors, has a director and writer who have worked on highly esteemed projects, and it’s the first big project to feature the pandemic while we’re still in the middle of a worldwide pandemic. It has temporary notoriety but is it any good?

Linda (Anne Hathaway) and her husband Paxton (Chiwetel Ejiofor) are stuck at home like everyone else in London thanks to COVID-19. He’s struggling for work and she’s struggling with the mental weight of her job and the impending knowledge her friends and co-workers will soon be laid off by Linda herself. The couple is also heading for a divorce, though they’re keeping that quiet from concerned family members checking in. Paxton’s sense of self is falling apart, and the rebellious biker who got into one unfortunate bar fight long ago seems to be fading. Now he doesn’t know what he’ll be and he’s forced to sell his prized motorcycle. Linda gets the idea to pull off a jewelry heist that she and Paxton have an unique opportunity for. Could it be the thing that makes them feel excited again? Could it bring them back together?

Locked Down has some significant tonal shifts but more so in ambition than execution, because at its core its really a talky, mumblecore relationship drama, but one that I found a little too lax and shapeless and ponderous to jibe with. Screenwriter Steven Knight can be a tremendous writer. He’s written Eastern Promises, Locke, Dirty Pretty Things, and created Peaky Blinders. He knows plot, he knows character, he knows structure. This, though, doesn’t feel so much like it was a script needing to be told as it was an experiment in could they make a movie about the pandemic and film it during the pandemic. The heist elements are rather haphazard and ultimately mean little to the overall storyline, merely serving as an instrument to reconcile our couple and force them to rely upon one another for a shared triumph (this shouldn’t be a spoiler). I think your overall view of Locked Down will depend upon your opinion of how the heist elements are handled. If it seemed like the start of something more exciting, more engaging, then you’ll be disappointed. If you didn’t care about the particulars of a heist during COVID times, and you didn’t want a more purely genre plot device to take over from the character-driven relationship drama,then you might be more charitable. For me, I love heist movies and the formula is ready-made for payoffs and entertainment. However, I also enjoy character-driven relationship dramas but I just wasn’t connecting with this one.

Locked Down has some significant tonal shifts but more so in ambition than execution, because at its core its really a talky, mumblecore relationship drama, but one that I found a little too lax and shapeless and ponderous to jibe with. Screenwriter Steven Knight can be a tremendous writer. He’s written Eastern Promises, Locke, Dirty Pretty Things, and created Peaky Blinders. He knows plot, he knows character, he knows structure. This, though, doesn’t feel so much like it was a script needing to be told as it was an experiment in could they make a movie about the pandemic and film it during the pandemic. The heist elements are rather haphazard and ultimately mean little to the overall storyline, merely serving as an instrument to reconcile our couple and force them to rely upon one another for a shared triumph (this shouldn’t be a spoiler). I think your overall view of Locked Down will depend upon your opinion of how the heist elements are handled. If it seemed like the start of something more exciting, more engaging, then you’ll be disappointed. If you didn’t care about the particulars of a heist during COVID times, and you didn’t want a more purely genre plot device to take over from the character-driven relationship drama,then you might be more charitable. For me, I love heist movies and the formula is ready-made for payoffs and entertainment. However, I also enjoy character-driven relationship dramas but I just wasn’t connecting with this one.

The characters of Paxton and Linda felt too overly written for me and lacking the more intriguing nuances that I find in the best of observational mumblecore cinema. To be fair, being overly written is not an indictment in itself. Quentin Tarantino characters are overly written and we love them. Viewers love big characters that demand your attention and equipped with monologues that we wish we could recite when life’s challenges afforded us the opportunity to wax poetic. The central agreement we have with characters, whether they’re realistically drawn or idiosyncratic or cartoonish, is that they need to at least be interesting. You need to want to spend time with the characters.

With Locked Down, I was getting as restless as the onscreen couple. I didn’t find them interesting because the same character notes were being hit over and over with little variation. The monologues, while having moments of life and personality, didn’t provide me greater insight at minute 80 than they did at minute 40. The experience felt like watching actors workshop characters and looking for extra meanings that seemed to be elusive. Listening to these characters talk more should make them more interesting, make them more personable, and make them more complex, right? While they uncork some well written asides, they’re each just rubbing the same nub of an identity crisis. The pacing also made the repetitive portions feel even longer. The metaphor of what Paxton’s motorcycle represents is so overblown and simplified. After spending so much time listening to these two bicker and argue in the same rooms, I was hoping for the heist as a needed escape, something that could finally serve to motivate the characters out of their pity parties and force them into a new conflict. I needed something, anything more to hold my waning attention. Alas, I finished Locked Down in the same patient, pursed-lip stupor as it began. These characters did not deserve this much extra breathing room.

With Locked Down, I was getting as restless as the onscreen couple. I didn’t find them interesting because the same character notes were being hit over and over with little variation. The monologues, while having moments of life and personality, didn’t provide me greater insight at minute 80 than they did at minute 40. The experience felt like watching actors workshop characters and looking for extra meanings that seemed to be elusive. Listening to these characters talk more should make them more interesting, make them more personable, and make them more complex, right? While they uncork some well written asides, they’re each just rubbing the same nub of an identity crisis. The pacing also made the repetitive portions feel even longer. The metaphor of what Paxton’s motorcycle represents is so overblown and simplified. After spending so much time listening to these two bicker and argue in the same rooms, I was hoping for the heist as a needed escape, something that could finally serve to motivate the characters out of their pity parties and force them into a new conflict. I needed something, anything more to hold my waning attention. Alas, I finished Locked Down in the same patient, pursed-lip stupor as it began. These characters did not deserve this much extra breathing room.

I like Hathaway (Colossal) and Ejiofar (12 Years a Slave). Watching them leap into what is essentially a two-hander filmed play sounds like a good bet for entertainment, especially with a writer with the credentials of Knight (we’ll ignore the outlandishly bonkers 2019 Serenity). Hathaway and Ejiofor are good together too. They have a spark that works, her anxiousness melding well with his dismissive pessimism. Again, the characters they’re portraying aren’t poorly written. There just isn’t enough polished material for them. That’s why each feels like they’re grasping to discover the character like it’s being formed in the moment. The entire movie feels like an overextended improv workshop everyone involved is developing in the moment. Good mumblecore movies can make you feel like a fly-on-the-wall with real people, but these characters are so overly written that an improv feeling doesn’t so much replicate the recognizable rhythms of life as it does an ungainly acting class in search of more direction and discretion. There are some other celebrity appearances in the form of Zoom cameos, and that’s something I’m not looking forward to with the incoming COVID movies, the ugly selfie aesthetic prevalence.

Locked Down feels more like an experiment to see if the filmmakers could make a movie under such unique and trying circumstances. It feels more like an acting exercise in need of more development and a little more vitality. There are fleeting moments that seem to tap into a universal despair and uncertainty many of us have wrestled with during our COVID isolation, but then the movie will just as likely throw in a hidden patch of poppies in a garden and a joke about nobody seeming to recognize the name Edgar Allen Poe. I watched Locked Down over the course of two nights, and mt girlfriend and I literally had forgotten we watched the first hour until coming across it again and going, “Oh yeah, we need to finish that after all.” I feel like that sums up the movie well. Within a day, I had already forgotten it, and that was before I even finished the full movie. They made a movie during COVID. Now make better ones in the future.

Locked Down feels more like an experiment to see if the filmmakers could make a movie under such unique and trying circumstances. It feels more like an acting exercise in need of more development and a little more vitality. There are fleeting moments that seem to tap into a universal despair and uncertainty many of us have wrestled with during our COVID isolation, but then the movie will just as likely throw in a hidden patch of poppies in a garden and a joke about nobody seeming to recognize the name Edgar Allen Poe. I watched Locked Down over the course of two nights, and mt girlfriend and I literally had forgotten we watched the first hour until coming across it again and going, “Oh yeah, we need to finish that after all.” I feel like that sums up the movie well. Within a day, I had already forgotten it, and that was before I even finished the full movie. They made a movie during COVID. Now make better ones in the future.

Nate’s Grade: C

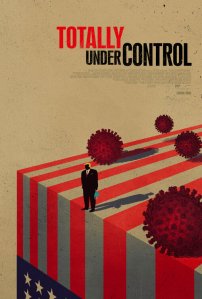

Totally Under Control (2020)

Over 220,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 as of this writing. We here in the U.S. are four percent of the world’s population and yet account for twenty-percent of the world’s deaths. I lament that this number will only go higher over the next many months of the pandemic that has defined 2020. Oscar-winning filmmaker Alex Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side, Going Clear, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room) and his co-directors Ophelia Harutyunyan and Suzanne Hillinger conducted interviews around the world with special cameras and protective measures to complete the first major documentary on the coronavirus outbreak. Totally Under Control (title taken directly from Trump’s early February response to COVID-19) is their collaborative effort, and it’s both a timely work of criticism and destined to be inevitably out-of-date in short order.

Over 220,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 as of this writing. We here in the U.S. are four percent of the world’s population and yet account for twenty-percent of the world’s deaths. I lament that this number will only go higher over the next many months of the pandemic that has defined 2020. Oscar-winning filmmaker Alex Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side, Going Clear, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room) and his co-directors Ophelia Harutyunyan and Suzanne Hillinger conducted interviews around the world with special cameras and protective measures to complete the first major documentary on the coronavirus outbreak. Totally Under Control (title taken directly from Trump’s early February response to COVID-19) is their collaborative effort, and it’s both a timely work of criticism and destined to be inevitably out-of-date in short order.

Given the constant deluge of news about the by-the-minute Trump administration mistakes and questionable calls, the question for a documentary like Totally Under Control is whether or not it provides more insights than simply keeping up with the shocking and dispiriting headlines. I would argue that Gibney’s first pass at recounting our still-living history of calamity offers the benefit of hindsight but also an immediacy or urgency, considering we are still months away from a presumable vaccine. The movie feels like what the first part of the COVID-19 mini-series would cover, focusing on those first few critical months of bungled government response from January to April. The abbreviated focus allows Gibney and his crew to zero in on what the early mistakes were and how we have been paying for them ever since. The collapsed time also allows for more get-able interview subjects, people who might not currently be serving in the administration who feel comfortable or compelled to go on the record with their accounts. There are some great interview subjects here that were plugged in from the beginning, sounding the alarm, and who can give the public a clear understanding of just how woefully equipped a deeply un-serious administration was to handle the most serious public health crisis in a century.

One of the more aggravating tragedies is that many of the thousands of COVID deaths could have been prevented if better steps had been taken early to contain its spread. Naturally, there’s always going to be clearer reflection when looking back on mistakes of the past, not knowing at the time that they were mistakes, but the Trump administration made a political calculus that would only exacerbate the spread of the coronavirus. Early on, the Trump administration’s guiding principle seemed to amount to stripping away anything and everything that the Obama administration had accomplished. It didn’t matter what it was, if Obama had built it, then Trump was motivated to tear it down. This included the pandemic response task force in 2018. This included ignoring the 70-page pandemic response playbook left behind. So when the early warnings appeared in December and January, the United States was already playing from behind. We could have been preparing with amping up production for necessary medical supplies and installing the infrastructure for a robust testing and tracing program; however, this all came into conflict with the other major political calculus that governed all of Trump’s decision-making. His mantra heading into 2020 and re-election was, simply, “Do no harm… to the economy.” Rather than take preventative measures or treat the virus as a danger, the Trump political apparatus was afraid acknowledging the threat so it would not spook the financial markets, a source of bragging for Trump to tout why the American people should re-elect him. When the CDC briefed government officials and media with updated predictions of normal life being uprooted, the markets responded negatively, and Trump fumed. From there, decisions were less about stopping the coronavirus and more about making everything appear like it was no big deal.

One of the more aggravating tragedies is that many of the thousands of COVID deaths could have been prevented if better steps had been taken early to contain its spread. Naturally, there’s always going to be clearer reflection when looking back on mistakes of the past, not knowing at the time that they were mistakes, but the Trump administration made a political calculus that would only exacerbate the spread of the coronavirus. Early on, the Trump administration’s guiding principle seemed to amount to stripping away anything and everything that the Obama administration had accomplished. It didn’t matter what it was, if Obama had built it, then Trump was motivated to tear it down. This included the pandemic response task force in 2018. This included ignoring the 70-page pandemic response playbook left behind. So when the early warnings appeared in December and January, the United States was already playing from behind. We could have been preparing with amping up production for necessary medical supplies and installing the infrastructure for a robust testing and tracing program; however, this all came into conflict with the other major political calculus that governed all of Trump’s decision-making. His mantra heading into 2020 and re-election was, simply, “Do no harm… to the economy.” Rather than take preventative measures or treat the virus as a danger, the Trump political apparatus was afraid acknowledging the threat so it would not spook the financial markets, a source of bragging for Trump to tout why the American people should re-elect him. When the CDC briefed government officials and media with updated predictions of normal life being uprooted, the markets responded negatively, and Trump fumed. From there, decisions were less about stopping the coronavirus and more about making everything appear like it was no big deal.

Totally Under Control keeps a running calendar of events to compare the U.S. response to South Korea, two countries that had their first official COVID infection on the same day. The Korean government had already taken preventative measures after the 2015 MERS scare to be ready if another frightening new contagion emerged. The politicians left the science to the scientists and followed their recommendations. The Korean people wore masks and were diligent about simple safety measures to stay safe. They had a system of contact tracing already installed. These moves are in sharp contrast to the American response, and while there would be some cultural roadblocks for Americans who consider themselves rugged individuals to submit themselves to a big data-harvesting consortium that contact tracing requires, we could have done so much better. In 1918, people wore masks because it made a real difference and saved lives. They took the Spanish flu epidemic seriously and they had fewer networks of knowledge at their disposal. Today, sadly, wearing a mask has become a political symbol and for many not wearing a mask has become a proud yet misguided act of defiance. Masks show consideration. Masks have been said to be even more effective at thwarting coronavirus spread than a vaccine. Masks work. The rest of the world, and South Korea, have showed what happens when you trust scientific recommendations. South Korea has less than 500 total COVID-19 deaths with a population of 52 million. Even if you multiply that figure by a generous seven to match the current U.S. population, that’s still only an estimated 3,500 total COVID-19 deaths during the same period.

The level of ineptitude is highlighted by two key interview subjects. Rick Bright was the director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) from 2016 to 2020. He filed a whistle-blower complaint about the Trump administration applying undue pressure to approve hydroxychloroquine, an experimental treatment that showed no signs of helping COVID patients. There was no medical reason to eliminate safeguards and protocols but the administration wanted a ready-to-market cure, and Bright was horrified that they wanted to make it widely available and over the counter, which would surely lead a panicked populace to request it and endanger their health. Recounting his experiences even brings Bright to tears as he recounts the disregard for safety and dereliction of duty of these political appointees dictating science. He’s a sobering and thoughtful voice to have in the documentary and also one of the biggest names of someone who worked inside the Trump response team. Another intriguing subject is Max Kennedy, who served on Jared Kushner’s White House supply chain task force. Kennedy thought he was going to be running errands or support tasks for the task force. He didn’t realize he and the other volunteers would be the entire task force. They were left to their personal laptops and emails to cold-call companies and perform Google searches to find personal protection equipment (PPE). They had no experience, no coordination with other government bodies, and they were competing against the federal government for the exact same dwindling supplies. Kennedy is breaking the NDA he was forced to sign to reveal the full extent of the chaos and inadequacy that Kushner’s “expertise” brought installing a solution to a very real problem. Kennedy and Bright’s first-hand insider accounts are both harrowing and maddening.

The level of ineptitude is highlighted by two key interview subjects. Rick Bright was the director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) from 2016 to 2020. He filed a whistle-blower complaint about the Trump administration applying undue pressure to approve hydroxychloroquine, an experimental treatment that showed no signs of helping COVID patients. There was no medical reason to eliminate safeguards and protocols but the administration wanted a ready-to-market cure, and Bright was horrified that they wanted to make it widely available and over the counter, which would surely lead a panicked populace to request it and endanger their health. Recounting his experiences even brings Bright to tears as he recounts the disregard for safety and dereliction of duty of these political appointees dictating science. He’s a sobering and thoughtful voice to have in the documentary and also one of the biggest names of someone who worked inside the Trump response team. Another intriguing subject is Max Kennedy, who served on Jared Kushner’s White House supply chain task force. Kennedy thought he was going to be running errands or support tasks for the task force. He didn’t realize he and the other volunteers would be the entire task force. They were left to their personal laptops and emails to cold-call companies and perform Google searches to find personal protection equipment (PPE). They had no experience, no coordination with other government bodies, and they were competing against the federal government for the exact same dwindling supplies. Kennedy is breaking the NDA he was forced to sign to reveal the full extent of the chaos and inadequacy that Kushner’s “expertise” brought installing a solution to a very real problem. Kennedy and Bright’s first-hand insider accounts are both harrowing and maddening.

When it appeared that the Trump administration wasn’t going to be able to contain COVID-19, that’s when they pivoted to shifting blame and responsibility onto the states. The Trump administration could have authorized the Defense Production Act to force companies to begin manufacturing very needed PPE, but they didn’t. They thought, as conservative dogma has preached for decades, that government is the problem and the private market will solve it all. The problem with this line of thinking is that there are certain powers the states do not have in comparison to the federal government. State governments cannot run past their budgets. State governments do not have the power to set up a national system of testing. State governments were forced into a 50-way fight for supplies and were vulnerable to capitalistic gouging. The states were then also competing with the federal government, which was driving up the bids for these supplies and then overpaying for the same supplies by many times over their cost. The states were left on their own to duke it out and any slip-ups or shortages were disparaged from afar by a Trump administration that wanted to look in charge but didn’t want the responsibility.

Totally Under Control is an essential documentary for our times but it also can’t help but feel like the beginning of an even bigger and more excoriating story. It’s frustratingly incomplete. It’s the opening chapter of the examination on the U.S. response to the coronavirus, and this story will likely only get more depressing and infuriating as the death toll rises and the regret of “what could have been” grows even more pressing with every week. Gibney and his fellow directors keep their movie pretty straightforward and efficient, and there is something powerful about putting all the relevant facts together into an easy to understand timeline and seeing all the dots connected. Gibney has always been blessed at his ability to artfully articulate a big picture with his films. Totally Under Control is a useful artifact for history and a denunciation of the early days when so much could have been so different if the United States had leaders that trusted science, didn’t dismantle key government bodies, took responsibility when the moment called upon rather than ducking leadership, and cared about more than their personal finances and standing. It’s only going to get worse from here, especially once we fully analyze all the important steps not taken.

Totally Under Control is an essential documentary for our times but it also can’t help but feel like the beginning of an even bigger and more excoriating story. It’s frustratingly incomplete. It’s the opening chapter of the examination on the U.S. response to the coronavirus, and this story will likely only get more depressing and infuriating as the death toll rises and the regret of “what could have been” grows even more pressing with every week. Gibney and his fellow directors keep their movie pretty straightforward and efficient, and there is something powerful about putting all the relevant facts together into an easy to understand timeline and seeing all the dots connected. Gibney has always been blessed at his ability to artfully articulate a big picture with his films. Totally Under Control is a useful artifact for history and a denunciation of the early days when so much could have been so different if the United States had leaders that trusted science, didn’t dismantle key government bodies, took responsibility when the moment called upon rather than ducking leadership, and cared about more than their personal finances and standing. It’s only going to get worse from here, especially once we fully analyze all the important steps not taken.

Nate’s Grade: B+

You must be logged in to post a comment.