Blog Archives

Black Mass (2015)

For decades, James “Whitey” Bulger (Johnny Depp) was the most feared man in Boston. After being released from Alcatraz, he returned home to his Massachusetts roots and consolidated power with an iorn grip. He and his cronies ruled Boston’s criminal underworld and were given protection from none other than the FBI. Thanks to agent John Connolly (Joel Edgerton), a childhood pal of Bulger’s, his crimes were given an implicit blessing (as long as he didn’t go too far) as he served as an FBI informant. In reality he was just ratting out his competition and abusing his power. This charade lasted for decades until Bulger went on the run, not being caught until 2011.

For decades, James “Whitey” Bulger (Johnny Depp) was the most feared man in Boston. After being released from Alcatraz, he returned home to his Massachusetts roots and consolidated power with an iorn grip. He and his cronies ruled Boston’s criminal underworld and were given protection from none other than the FBI. Thanks to agent John Connolly (Joel Edgerton), a childhood pal of Bulger’s, his crimes were given an implicit blessing (as long as he didn’t go too far) as he served as an FBI informant. In reality he was just ratting out his competition and abusing his power. This charade lasted for decades until Bulger went on the run, not being caught until 2011.

Black Mass really suffers from its two core characters, Bulger and Connolly, who are just not that interesting, which is a great surprise for a true-story about corruption and murder. Crime drama have an allure to them and this is accentuated by their colorful and usually larger-than-life figures that we watch commit all those terrible yet cinematic acts of vicious violence. Being the inspiration for Jack Nicholson’s crime lord in The Departed, you’d assume that the real-life Bulger would have a menace and personality that fills up the big screen, leaving you asking for more. Shockingly, he doesn’t. He’s a mean guy and he has his moments of severe intimidation, but he’s also practically a 1990s action movie villain with a sneer and one-dimensional sense of posturing. He doesn’t come across as a character but more as a boogeyman. We see him help some old ladies in the neighborhood, but you never get a sense he has any care or loyalty for his old stomping grounds, especially as he pumps drugs into the impoverished community. We don’t get any sense about how his mind works or what motivates Bulger beyond unchecked greed. We don’t get a sense of any discernable personality. We don’t have any scene that feels tailored toward the character (even though I assume many are based on true events); instead, Bulger feels unmoored and generally unimportant to Black Mass because he could be replaced by any standard movie tough guy. How in the world has a movie about notorious criminal Whitey Bulger found a way to make him this boring?

Then there are the underdeveloped supporting characters of Connolly and Bulger’s brother, Billy (Benedict Cumberbatch). The guy responsible for Bulger’s misdeeds getting the green light should be a far more important person in this story but he’s mostly portrayed as a stooge. He wants to look out for Bulger but despite one “you’ve changed” speech from his beleaguered wife, you don’t truly get any sense that Connolly has changed. You don’t get a sense of his moral dilemma or even his desperation as new leadership in the FBI starts to see through his poor obfuscations. He’s a stooge from the beginning and we feel nothing when his self-serving alliance comes to an unceremonious end. There is even less when it comes to Billy, a character that seems to pretend his brother is a different person. Billy works as a state senator. His political position must have supplied more inherent drama than what they movie affords. Black Mass is doomed when its three central characters are this dull.

Then there are the underdeveloped supporting characters of Connolly and Bulger’s brother, Billy (Benedict Cumberbatch). The guy responsible for Bulger’s misdeeds getting the green light should be a far more important person in this story but he’s mostly portrayed as a stooge. He wants to look out for Bulger but despite one “you’ve changed” speech from his beleaguered wife, you don’t truly get any sense that Connolly has changed. You don’t get a sense of his moral dilemma or even his desperation as new leadership in the FBI starts to see through his poor obfuscations. He’s a stooge from the beginning and we feel nothing when his self-serving alliance comes to an unceremonious end. There is even less when it comes to Billy, a character that seems to pretend his brother is a different person. Billy works as a state senator. His political position must have supplied more inherent drama than what they movie affords. Black Mass is doomed when its three central characters are this dull.

Another problem is that the movie makes Bulger too protected for too long to the point it becomes comical. The script follows a routine where an associate of Bulger’s knows too much or is going to confess to the police, and within usually the next scene that character is easily dispatched, sometimes in broad daylight and with scores of witnesses. There are several recognizable actors who must have filmed for a weekend. I understand Connolly was protecting his meal ticket here with the Bureau, but Bulger is so brazen that we as an audience need more justification for how Connolly could cover for so long. It feels like Bulger has free reign and that extends into the screenplay as well. Without a stronger sense of opposition, or at least watching Bulger rise through the mob ranks, we’re left with a collection of scenes of the status quo being repeatedly reconfirmed.

I’ve figured out the way to revise Black Mass and make it far more entertaining. As stated above, Bulger is just too much a one-note boogeyman to deserve the screen time he’s given, and his onscreen dominance hampers what should be the movie’s true focus, Agent Connolly. Here is where the movie’s focal point should be because this is the transformation of a person. Bulger is the same from start to finish, only shifting in degrees of power, but it’s Connolly who goes on the moral descent. His is the more interesting journey, as he tries to use his childhood connections to get ahead in the FBI, but he consistently has to make compromise after compromise, and after awhile he’s gone too deep. Now he has to worry about being caught or being too expendable to Bulger. This character arc, given its proper due, would make for a terrific thriller that’s also churning with an intense moral ambiguity of a man trying to justify the choices he has made to stay ahead. It’s a more tragic hero sort of focus but one that has far more potential to illuminate the inner anxiety and psychological torment of the human heart rather than constantly going back to Buger to watch him whack another person. It’s far more interesting to watch a man sink into the mire he has knowingly constructed, and that’s why the narrative needed to shift its focus to Connolly to really succeed.

Depp (Pirates of the Caribbean) takes a few steps back from his more eccentric oddballs to portray the unnerving ferocity of Bulger, and he’s quite good at playing a human being again, though Bulger strains the definition of human. He underplays several scenes and his eyes burrow into you with such animosity that it might make you shudder. He’s a thoroughly convincing cold-blooded killer, though I wonder if part of my praise is grading Depp on a curve since Bulger is so unlike his recent parts. Regardless, Depp is the most enjoyable aspect of Black Mass and a reconfirmation that he can be a peerless actor when he sinks his teeth into a role rather than a series of tics. He also handles the Boston accent far better than his peers. Cumberbatch (The Imitation Game) and Edgerton (The Gift) are more than capable actors but oh boy do both flounder with their speaking voices. They are greatly miscast as two native Massachusetts sons.

Depp (Pirates of the Caribbean) takes a few steps back from his more eccentric oddballs to portray the unnerving ferocity of Bulger, and he’s quite good at playing a human being again, though Bulger strains the definition of human. He underplays several scenes and his eyes burrow into you with such animosity that it might make you shudder. He’s a thoroughly convincing cold-blooded killer, though I wonder if part of my praise is grading Depp on a curve since Bulger is so unlike his recent parts. Regardless, Depp is the most enjoyable aspect of Black Mass and a reconfirmation that he can be a peerless actor when he sinks his teeth into a role rather than a series of tics. He also handles the Boston accent far better than his peers. Cumberbatch (The Imitation Game) and Edgerton (The Gift) are more than capable actors but oh boy do both flounder with their speaking voices. They are greatly miscast as two native Massachusetts sons.

If you’re a fan of crime thrillers steeped in true-life details of heinous men (it’s typically men) committing heinous acts, even you will likely be underwhelmed or marginally disappointed by Black Mass. There just isn’t enough going on here besides a series of bad events that don’t feel like they properly escalate, complicate, or alter our characters until the film’s very end when the plot requires it. The screenplay has propped up Bulger by his rep, told Depp to crank up his considerable glower, and called it a day. It’s a Boston mob story that needed more intensive attention to its characters to survive. Black Mass is a crime story that dissolves into its stock period details and genre trappings, becoming a good-looking but ultimately meaningless window into a hidden world.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Straight Outta Compton (2015)

In 1987 in Compton, Eazy-E (Jason Mitchell) was selling drugs, Dr. Dre (Corey Hawkins) was spinning records in a club, and Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson Jr.) is writing lyrics in the back of a school bus (the movie significantly downplays DJ Yella and MC Ren). The guys have grown up in an environment of suspicions and harassment by the Los Angeles police. Their response was to compose angry and defiant songs illuminating their world. After a few early performances, the group is approached by record producer Jerry Heller (Paul Giamatti) who wants to get them signed and touring. Their music and their perspective catches on and soon NWA is awash in big shows and groupies. Heller puts more of his efforts onto Eazy-E, and Dre and Cube feel marginalized and doubtful that Heller has their best interest at heart.

In 1987 in Compton, Eazy-E (Jason Mitchell) was selling drugs, Dr. Dre (Corey Hawkins) was spinning records in a club, and Ice Cube (O’Shea Jackson Jr.) is writing lyrics in the back of a school bus (the movie significantly downplays DJ Yella and MC Ren). The guys have grown up in an environment of suspicions and harassment by the Los Angeles police. Their response was to compose angry and defiant songs illuminating their world. After a few early performances, the group is approached by record producer Jerry Heller (Paul Giamatti) who wants to get them signed and touring. Their music and their perspective catches on and soon NWA is awash in big shows and groupies. Heller puts more of his efforts onto Eazy-E, and Dre and Cube feel marginalized and doubtful that Heller has their best interest at heart.

It’s hard to reconcile the brash and challenging men responsible for NWA and this sanitized and rather rote rags-to-riches biopic that asks curiously little of its subjects when it comes to depth or reflection. Not every biopic needs to be as faithful as the most excoriating documentary on its subject, but we have become accustomed over the last decade to the warts-and-all approach, where the central biographical figures are celebrated for their achievements but care is taken to tell their lives with measured accuracy, not to hide anything that challenges our concept of who these people were. Imagine if Walk the Line had sanitized its portrayal of Johnny Cash, or worse, devoted most of its running time to his stint as a revivalist Christian musician? What if Ray had eliminated his womanzing? What if The Aviator said that Howard Hughes was the model of human sanity? A biopic doesn’t need to tell us every facet of its subject’s life because that is an impossible demand that only the densest of books can truly achieve, however, a biopic must instill the spirit of its subject in an honest representation, because that’s at best what you’re going to get when you apply a human life to the realm of narrative. Straight Outta Compton comes across as far too gentle with its core subjects, portraying them as underdog anti-heroes who were pushed around by those trying to exploit them and their message. Of course this would be the approach when Dr. Dre, Ice Cube, and the widow of Eazy-E produce the film. At this point it’s about protecting the legacy, protecting the brand, and so the members of NWA become far less interesting.

Nobody probably gets the biggest revision than Dr. Dre, especially his violent history with women. As depicted in the film, Dre is a talented and frustrated music producer who is trying to do his best to live up to his dreams but falling short and feeling the pressure of not being the support system for his brother, his girlfriend, his daughter. When the money starts rolling in, Dre embarks on a successful solo career and reconciles with Eazy-E. That’s about all there is to his character arc, a series of creative struggles and trusting the wrong people. There is one very brief moment that hints at Dre’s history with women, when his girlfriend expresses caution about getting too involved with Dre because she doesn’t want anything negative to happen to her young son. This woman doesn’t appear to be Michel’le Toussaint, a best-selling Ruthless Records artist who was with Dre for seven years and gave birth to their son in 1991. Toussaint has spoken about consistent physical abuse, including an incident where Dre shot at her through a bathroom door. Then there’s the glaring omission of Dee Barnes, a journalist who Dre brutally beat inside a nightclub in 1990 (Dre has finally come forward and apologized for this incident but only after the Apple overlords or Universal execs probably applied some pressure to make the bad PR from the press tamp down). Director F. Gary Gray (Friday, Law Abiding Citizen) has gone on record saying they had to focus on the “story that was pertinent to our main characters.” About that…

Nobody probably gets the biggest revision than Dr. Dre, especially his violent history with women. As depicted in the film, Dre is a talented and frustrated music producer who is trying to do his best to live up to his dreams but falling short and feeling the pressure of not being the support system for his brother, his girlfriend, his daughter. When the money starts rolling in, Dre embarks on a successful solo career and reconciles with Eazy-E. That’s about all there is to his character arc, a series of creative struggles and trusting the wrong people. There is one very brief moment that hints at Dre’s history with women, when his girlfriend expresses caution about getting too involved with Dre because she doesn’t want anything negative to happen to her young son. This woman doesn’t appear to be Michel’le Toussaint, a best-selling Ruthless Records artist who was with Dre for seven years and gave birth to their son in 1991. Toussaint has spoken about consistent physical abuse, including an incident where Dre shot at her through a bathroom door. Then there’s the glaring omission of Dee Barnes, a journalist who Dre brutally beat inside a nightclub in 1990 (Dre has finally come forward and apologized for this incident but only after the Apple overlords or Universal execs probably applied some pressure to make the bad PR from the press tamp down). Director F. Gary Gray (Friday, Law Abiding Citizen) has gone on record saying they had to focus on the “story that was pertinent to our main characters.” About that…

Straight Outta Compton has a renewed relevancy due to the increased attention in the news concerning police brutality, profiling, and harassment. It was from this combination of oppression and negativity that NWA honed their provocative message. The lyrics of gangster rap reflected the reality of their living conditions, and so they were bleak, angry, violent, and they spurred a sense of relatability across the country from others. It was a reaction against a system that had cataloged them as suspects from birth. The story structure of Straight Outta Compton shows the birth of gangster rap through a select sample of personal experiences. From there we see the rise, the backlash, and I suppose a “we told you so” moment with the aggravation over the Rodney King case turning into the volcanic anger and destruction of the L.A. riots. The aside highlighting the L.A. riots only really serves to underline the idea that NWA’s message of the beaten-down growing increasingly weary of their denigrated treatment. After that, the greater message of what NWA meant to the world of music and culture is lost midst the squabbles of the former friends. This is a missed opportunity at creating a stronger message and adding needed complexity to the main characters. What if Straight Outta Compton had explored the violent life of its stars after they had achieved their dreams? It creates a more damning theme about the consequences of a life under oppression; Dre grew up being harassed and antagonized, which is reflected in their music, but even when they escape that environment the consequences can still follow and entrap them. As it plays, the guys strike it rich, get waylaid by outsiders, and eventually find their footing again. It’s a narrative structure that places all the problems as external threats, be it Heller or Knight or HIV itself, and strips the main characters of their own agency. The movie doesn’t let them account for their own action and finds excuses when able. An incident where they brandish high-powered guns to chase off an angry boyfriend is treated as an unearned and questionable moment of levity. Gray said they could only focus on the “pertinent” stories, but I don’t see anything more pertinent than exploring the psychological trauma of brutality and oppression and how, even as an adult with seemingly the world at your fingertips, it still manifests in your life and personal relationships.

As a standard rags-to-riches biopic, Straight Outta Compton is consistently entertaining and well acted, though it can’t help but feel like we’re rushing through the events. A significant disappointment is the underdeveloped nature of the friendship of Dre, Eazy-E and Cube. There’s an early scene where they’re teasing one another and working out the beginnings of “Boys in the Hood” and this is the lone moment where we feel the dynamic of the trio. The early glimpse at the creative process is a high-point. After that, sadly, the only examination the movie affords on the relationships of the three is the jealousies and divisions. Strangely, the most interesting character relationship is between Eazy-E and Heller, which despite the predictable dissolution is the most heartfelt relationship on screen. Think about that: the most involving relationship depicted in the movie is between a former drug dealer-turned-musician and a Jewish music producer. It’s their opposites-attract dynamic that helps to make them so much more intriguing to watch.

Straight Outta Compton treats Heller as a greedy predator who was cheating NWA out of their rightful earnings, though I’m still a bit skeptical as to these accusations. The movie even gives me a reason to support my skepticism. Once Cube goes solo, a record producer (Tate Ellington) promises to support him on his next record if the first is successful. Obviously Cube is a hit and he comes back to this producer, who explains that he can’t simply just write a check then and there and that it’s more complicated. Cube responds by trashing the guy’s office and the moment is treated as a strangely triumphant moment that the exec even awkwardly jokes about later when Cube returns. This moment made me think maybe, just maybe, the people in the industry weren’t explicitly cheating out NWA but the margins of the recording industry are a bit harder to explain.

Straight Outta Compton treats Heller as a greedy predator who was cheating NWA out of their rightful earnings, though I’m still a bit skeptical as to these accusations. The movie even gives me a reason to support my skepticism. Once Cube goes solo, a record producer (Tate Ellington) promises to support him on his next record if the first is successful. Obviously Cube is a hit and he comes back to this producer, who explains that he can’t simply just write a check then and there and that it’s more complicated. Cube responds by trashing the guy’s office and the moment is treated as a strangely triumphant moment that the exec even awkwardly jokes about later when Cube returns. This moment made me think maybe, just maybe, the people in the industry weren’t explicitly cheating out NWA but the margins of the recording industry are a bit harder to explain.

While the characters themselves can be a tad boring, the actors do everything in their power to make them feel fully felt. The three lead actors impressed me. Mitchell especially wows in his greater emotional moments, like the discovery of being HIV-positive and only having a few reaming months to live. Jackson Jr. gives an eerily accurate portrayal of his father, and Hawkins (Non-Stop) hits his stride when Dre is most ambitious. The three of them have an easy-going camaraderie that adds to the authenticity. The actors are so good that the deficiencies in characterization are all the more frustrating. The talent was there but the characterization was not. I also want to single out R. Marcos Taylor for his strikingly imposing portrayal of Suge Knight. As soon as Taylor starts eating up more screen time, I couldn’t help but wish the movie’s focus jumped ship to the ruthless Death Row Records impresario.

Straight Outta Compton is already the highest-grossing musical biopic of all time, so surely the wider moviegoing public greeted its safe approach to its subjects with some level of approval. Enough time has passed to add a layer of nostalgia to the early days of gangster rap, as well as political relevancy with the increased media spotlight on overzealous police provocations and the growing Black Lives Matter movement. The time was ripe for this movie and it’s an undeniable hit. I was entertained throughout and found the performances to be involving, but I can’t shake off the feeling about what is being left out. It’s by no means a biopic’s requirement to include everything about its subject, but with the living members of NWA aboard and approving their movie versions, the sanitization of a complicated and contradictory reality is the best we’re going to get. The film doesn’t hold the band up for their behavior, whether it’s promiscuous sex that leads Eazy-E to getting infected (a plot point with no setup beyond some movie-friendly knowing coughs) or Dre’s violent history with women. The move doesn’t have to portray the members of NWA as villains but by treating them as misunderstood underdogs who were exploited by outside forces feels like a (forgive the term) cop-out. These guys didn’t ask to become spokemen for a generation of antagonized and discredited black men, but surely there’s something more interesting and deeper to explore than band in-fighting. Straight Outta Compton is a slick and entertaining film but ultimately just another product.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Child 44 (2015)

Unfairly cast out like some unwanted vermin, Child 44 is a police procedural based on a best-selling novel that the studio simply wanted to get rid of quietly. It was “dumped” into theaters and, as expected, began its disappearing act. That’s a shame, because it’s actually a rather involving mystery and an especially fascinating perspective into a little known world of being a cop on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Tom Hardy plays Leo, a member of the Soviet state police who is tracking a serial murderer preying upon orphaned children across the countryside in 1953. His wife (Noomi Rapace) is terrified of him and secretly a rebel informer. The two of them get banished to a Soviet outpost when Leo refuses to turn her in; he also refuses to accept the state’s conclusion over the dead children. In a weirdly perplexing turn, the Soviet Union believed murder was a Western byproduct. “There is no murder in paradise,” we are told several times, and since the U.S.S.R. is a communist worker’s “paradise,” whatever reality that doesn’t jibe with the party line is swept away. The murder mystery itself is fairly well developed and suspenseful, but it’s really the glimpse into this bleak and paranoid world that I found so intriguing. Child 44 is a slowly paced film thick with the details of establishing the dour existence of Soviet Union life. You truly get a sense of how wearying and beaten down these people’s lives were, how trapped they felt, how justifiable their paranoia was. The husband and wife relationship grows as they’re forced to reevaluate their sense of one another, and it genuinely becomes a meaty dramatic addition. Child 44 is a slow movie but the pacing serves the deliberate and oppressive tone of the film. It’s a film with some problems and missteps (certain antagonists make little sense in their motivations), including some incoherent action/fight scenes (fighting in the mud? Way to visually obscure everybody, guys). However, this is a better movie than the studio, and a majority of critics, would have you believe. It’s engrossing and taut and ambiguous and consistently interesting, with another standout performance by Hardy. Like many of the characters, this movie deserved a better fate.

Unfairly cast out like some unwanted vermin, Child 44 is a police procedural based on a best-selling novel that the studio simply wanted to get rid of quietly. It was “dumped” into theaters and, as expected, began its disappearing act. That’s a shame, because it’s actually a rather involving mystery and an especially fascinating perspective into a little known world of being a cop on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Tom Hardy plays Leo, a member of the Soviet state police who is tracking a serial murderer preying upon orphaned children across the countryside in 1953. His wife (Noomi Rapace) is terrified of him and secretly a rebel informer. The two of them get banished to a Soviet outpost when Leo refuses to turn her in; he also refuses to accept the state’s conclusion over the dead children. In a weirdly perplexing turn, the Soviet Union believed murder was a Western byproduct. “There is no murder in paradise,” we are told several times, and since the U.S.S.R. is a communist worker’s “paradise,” whatever reality that doesn’t jibe with the party line is swept away. The murder mystery itself is fairly well developed and suspenseful, but it’s really the glimpse into this bleak and paranoid world that I found so intriguing. Child 44 is a slowly paced film thick with the details of establishing the dour existence of Soviet Union life. You truly get a sense of how wearying and beaten down these people’s lives were, how trapped they felt, how justifiable their paranoia was. The husband and wife relationship grows as they’re forced to reevaluate their sense of one another, and it genuinely becomes a meaty dramatic addition. Child 44 is a slow movie but the pacing serves the deliberate and oppressive tone of the film. It’s a film with some problems and missteps (certain antagonists make little sense in their motivations), including some incoherent action/fight scenes (fighting in the mud? Way to visually obscure everybody, guys). However, this is a better movie than the studio, and a majority of critics, would have you believe. It’s engrossing and taut and ambiguous and consistently interesting, with another standout performance by Hardy. Like many of the characters, this movie deserved a better fate.

Nate’s Grade: B

Inherent Vice (2014)

This is one of the most difficult reviews I’ve ever had to write. It’s not because I’m torn over the film; no, it’s because this review will also serve as my break-up letter. Paul Thomas Anderson (PTA), we’re just moving in two different directions. We met when we were both young and headstrong. I enjoyed your early works Paul, but then somewhere around There Will be Blood, things changed. You didn’t seem like the PTA I had known to love. You became someone else, and your films represented this change, becoming plotless and laborious centerpieces on self-destructive men. Others raved to the heavens over Blood but it left me cold. Maybe I’m missing something, I thought. Maybe the problem is me. Maybe it’s just a phase. Then in 2012 came The Master, a pretentious and ultimately futile exercise anchored by the wrong choice for a main character. When I saw the early advertisements for Inherent Vice I got my hopes up. It looked like a weird and silly throwback, a crime caper that didn’t take itself so seriously. At last, I thought, my PTA has returned to me. After watching Inherent Vice, I can no longer deny the reality I have been ducking. My PTA is gone and he’s not coming back. We’ll always have Boogie Nights, Paul. It will still be one of my favorite films no matter what.

This is one of the most difficult reviews I’ve ever had to write. It’s not because I’m torn over the film; no, it’s because this review will also serve as my break-up letter. Paul Thomas Anderson (PTA), we’re just moving in two different directions. We met when we were both young and headstrong. I enjoyed your early works Paul, but then somewhere around There Will be Blood, things changed. You didn’t seem like the PTA I had known to love. You became someone else, and your films represented this change, becoming plotless and laborious centerpieces on self-destructive men. Others raved to the heavens over Blood but it left me cold. Maybe I’m missing something, I thought. Maybe the problem is me. Maybe it’s just a phase. Then in 2012 came The Master, a pretentious and ultimately futile exercise anchored by the wrong choice for a main character. When I saw the early advertisements for Inherent Vice I got my hopes up. It looked like a weird and silly throwback, a crime caper that didn’t take itself so seriously. At last, I thought, my PTA has returned to me. After watching Inherent Vice, I can no longer deny the reality I have been ducking. My PTA is gone and he’s not coming back. We’ll always have Boogie Nights, Paul. It will still be one of my favorite films no matter what.

In the drug-fueled world of 1970 Los Angeles, stoner private eye Doc (Joaquin Phoenix) is visited by one of his ex-girlfriends, Shasta (Katherine Waterston). She’s in a bad place. The man she’s in love with, the wealthy real estate magnate Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts) is going to be conned. Mickey’s wife, and her boyfriend, is going to commit the guy to a mental hospital ward and take control of his empire. Then Shasta and Mickey go missing. Doc asks around, from his police detective contact named Bigfoot (Josh Brolin), to an ex (Reese Witherspoon) who happens to be in the L.A. justice department, to a junkie (Jena Malone) with a fancy set of fake teeth thanks to a coked-out dentist (Martin Short) who may be a front for an Asian heroin cartel. Or maybe not. As more and more strange characters come into orbit, Doc’s life is placed in danger, and all he really wants to find out is whether his dear Shasta is safe or not.

In the drug-fueled world of 1970 Los Angeles, stoner private eye Doc (Joaquin Phoenix) is visited by one of his ex-girlfriends, Shasta (Katherine Waterston). She’s in a bad place. The man she’s in love with, the wealthy real estate magnate Mickey Wolfmann (Eric Roberts) is going to be conned. Mickey’s wife, and her boyfriend, is going to commit the guy to a mental hospital ward and take control of his empire. Then Shasta and Mickey go missing. Doc asks around, from his police detective contact named Bigfoot (Josh Brolin), to an ex (Reese Witherspoon) who happens to be in the L.A. justice department, to a junkie (Jena Malone) with a fancy set of fake teeth thanks to a coked-out dentist (Martin Short) who may be a front for an Asian heroin cartel. Or maybe not. As more and more strange characters come into orbit, Doc’s life is placed in danger, and all he really wants to find out is whether his dear Shasta is safe or not.

Inherent Vice is a shaggy dog detective tale that is too long, too convoluted, too slow, too mumbly, too confusing, and not nearly funny or engaging enough. If it weren’t for the enduring pain that was The Master, this would qualify as Anderson’s worst picture.

One of my main complaints of Anderson’s last two movies has been the paucity of a strong narrative, especially with the plodding Master. It almost felt like Anderson was, subconsciously or consciously, evening the scales from his plot-heavy early works. Being plotless is not a charge one can levy against Inherent Vice. There is a story here with plenty of subplots and intrigue. The problem is that it’s almost never coherent, as if the audience is lost in the same pot haze as its loopy protagonist. The mystery barely develops before the movie starts heaping subplot upon subplot, each introducing more and more characters, before the audience has a chance to process. It’s difficult to keep all the characters and their relationships straight, and then just when you think you have everything settled, the film provides even more work. The characters just feel like they’re playing out in different movies (some I would prefer to be watching), with the occasional crossover. I literally gave up 45 minutes into the movie and accepted the fact that I’m not going to be able to follow it, so I might as well just watch and cope. This defeatist attitude did not enhance my viewing pleasure. The narrative is too cluttered with side characters and superfluous digressions.

The plot is overstuffed with characters, many of which will only appear for one sequence or even one scene, thus polluting a narrative already crammed to the seams with characters to keep track of. Did all of these characters need to be here and visited in such frequency? Doc makes for a fairly frustrating protagonist. He’s got little personality to him and few opportunities to flesh him out. Not having read Thomas Pynchon’s novel, I cannot say how complex the original character was that Anderson had to work with. Doc just seems like a placeholder for a character, a guy who bumbles about with a microphone, asking others questions and slowly unraveling a convoluted conspiracy. He’s more a figure to open other characters up than a character himself. The obvious comparison to the film and the protagonist is The Big Lebowski, a Coen brothers film I’m not even that fond over. However, with Lebowski, the Coens gave us memorable characters that separated themselves from the pack. The main character had a definite personality even if he was drunk or stoned for most of the film. Except for Short’s wonderfully debased and wily five minutes onscreen, every character just kind of washes in and out of your memory, only registering because of a famous face portraying him or her. Even in the closing minutes, the film is still introducing vital characters. The unnecessary narration by musician Joanna Newsome is also dripping with pretense.

Another key factor that limits coherency is the fact that every damn character mumbles almost entirely through the entirety of the movie. And that entirety, by the way, is almost two and a half hours, a running time too long by at least 30 minutes, especially when Doc’s central mystery of what happened to Shasta is over before the two-hour mark. For whatever reason, it seems that Anderson has given an edict that no actor on set can talk above a certain decibel level or enunciate that clearly. This is a film that almost requires a subtitle feature. There are so many hushed or mumbled conversations, making it even harder to keep up with the convoluted narrative. Anderson’s camerawork can complicate the matter as well. Throughout the film, he’ll position his characters speaking and slowly, always so slowly, zoom in on them, as if we’re eavesdropping. David Fincher did something similar with his sound design on Social Network, amping up the ambient noise to force the audience to tune their ears and pay closer attention. However, he had Aaron Sorkin’s words to work with, which were quite worth our attention. With Inherent Vice, the characters talk in circles, tangents, and limp jokes. After a protracted setup, and listening to one superficially kooky character after another, you come to terms with the fact that while difficult to follow and hear, you’re probably not missing much.

Another key factor that limits coherency is the fact that every damn character mumbles almost entirely through the entirety of the movie. And that entirety, by the way, is almost two and a half hours, a running time too long by at least 30 minutes, especially when Doc’s central mystery of what happened to Shasta is over before the two-hour mark. For whatever reason, it seems that Anderson has given an edict that no actor on set can talk above a certain decibel level or enunciate that clearly. This is a film that almost requires a subtitle feature. There are so many hushed or mumbled conversations, making it even harder to keep up with the convoluted narrative. Anderson’s camerawork can complicate the matter as well. Throughout the film, he’ll position his characters speaking and slowly, always so slowly, zoom in on them, as if we’re eavesdropping. David Fincher did something similar with his sound design on Social Network, amping up the ambient noise to force the audience to tune their ears and pay closer attention. However, he had Aaron Sorkin’s words to work with, which were quite worth our attention. With Inherent Vice, the characters talk in circles, tangents, and limp jokes. After a protracted setup, and listening to one superficially kooky character after another, you come to terms with the fact that while difficult to follow and hear, you’re probably not missing much.

Obviously, Inherent Vice is one detective mystery where the answers matter less than the journey and the various characters that emerge, but I just didn’t care, period. It started too slow, building a hazy atmosphere that just couldn’t sustain this amount of prolonged bloat and an overload of characters. Anderson needed to prune Pynchon’s novel further. What appears onscreen is just too difficult to follow along, and, more importantly, not engaging enough to justify the effort. The characters fall into this nether region between realism and broadly comic, which just makes them sort of unrealistic yet not funny enough. The story rambles and rambles, set to twee narration that feels like Newsome is just reading from the book, like Anderson could just not part with a handful of prose passages in his translation. Much like The Master, I know there will be champions of this movie, but I won’t be able to understand them. This isn’t a zany Chinatown meets Lewboswki. This isn’t some grand throwback to 1970s cinema. This isn’t even much in the way of a comedy, so be forewarned. Inherent Vice is the realization for me that the Paul Thomas Anderson I fell in love with is not coming back. And that’s okay. He’s allowed to peruse other movies just as I’m allowed to see other directors. I wish him well.

Nate’s Grade: C+

A Walk Among the Tombstones (2014)

Scott Frank has only directed one movie, The Lookout, but as a screenwriter his fingerprints are everywhere in Hollywood. The man’s name is all over projects such as Out of Sight, Minority Report, Get Shorty, The Wolverine, Marley & Me, and those are just the ones that made it across the finish line. As any aspiring screenwriter knows, Hollywood is built upon an ever-amassing burial ground of unproduced screenplays. A Walk Among the Tombstones is only his second directing feature, which tells me it must have had significant personal value for this famous scribe. You can definitely tell Frank has an affinity for hard-boiled film noir of old, though the splashes of in-your-face sadism may be too much for certain audiences. It’s a genre movie all right, but it’s also a grisly one that bothers to take its time setting up character, plot, and resolution.

Scott Frank has only directed one movie, The Lookout, but as a screenwriter his fingerprints are everywhere in Hollywood. The man’s name is all over projects such as Out of Sight, Minority Report, Get Shorty, The Wolverine, Marley & Me, and those are just the ones that made it across the finish line. As any aspiring screenwriter knows, Hollywood is built upon an ever-amassing burial ground of unproduced screenplays. A Walk Among the Tombstones is only his second directing feature, which tells me it must have had significant personal value for this famous scribe. You can definitely tell Frank has an affinity for hard-boiled film noir of old, though the splashes of in-your-face sadism may be too much for certain audiences. It’s a genre movie all right, but it’s also a grisly one that bothers to take its time setting up character, plot, and resolution.

It’s New York City on the cusp of Y2K, and retired cop Matt Scudder (Liam Neeson) is just trying to enjoy his dinner. He’s pulled into a complex kidnapping scenario at the behest of one of his AA peers. Two men have been targeting the city’s drug traffickers, men with big pockets who cannot go to the police. These psychopaths enjoy abducting the trafficker’s wives, ransoming them for hundreds of thousands, and then slicing and dicing their victims anyway. Matt initially turns down the offer, working around the edges f the law, but the viciousness is too much to ignore. He reawakens his old detective habbits, falling back into a routine, and tracking down those responsible.

Those expecting a regular Liam Neeson afternoon of top-draw face punching may be in for a slight disappointment, because A Walk Among the Tombstones is a gritty detective tale that swims amidst an ocean of moral decay and queasy sexual violence. It’s a detective yarn that unwinds at a casual pace but one that feels like a natural connecting of plot points. Thankfully, this isn’t a movie that treats the identity of the killers as a mystery that needs to be dragged out as long as possible, with the ultimate pained reveal being one of the otherwise harmless characters we’ve previously been introduced. We know who these two psychopaths are after about twenty minutes, so there’s no prolonged guessing game. Rather than linger on who they are we now await the ultimate satisfaction of Matt Scuder finally facing off against our two psychopathic killers, and they are indeed psychopaths. These two are very wicked men, gathering sadistic pleasure from torturing their captive women. The two men are kept as unsettling ciphers; we don’t know much about them except they have an addiction to killing. It’s not about the hundreds of thousands they scam from the drug traffickers; it’s really about the thrill of the hunt. While I wish there was more depth, they were menacing enough. I was itchy with anticipation for them to get some comeuppance. I’ve read reviews indicating that our two remorseless killers are a gay couple; if this is true it’s kept very vague for interpretation. In the age of equality, it could be homophobic to declare, in absolutes, that psychopathic killers couldn’t also be gay or lesbian. That would be… wrong?

Those expecting a regular Liam Neeson afternoon of top-draw face punching may be in for a slight disappointment, because A Walk Among the Tombstones is a gritty detective tale that swims amidst an ocean of moral decay and queasy sexual violence. It’s a detective yarn that unwinds at a casual pace but one that feels like a natural connecting of plot points. Thankfully, this isn’t a movie that treats the identity of the killers as a mystery that needs to be dragged out as long as possible, with the ultimate pained reveal being one of the otherwise harmless characters we’ve previously been introduced. We know who these two psychopaths are after about twenty minutes, so there’s no prolonged guessing game. Rather than linger on who they are we now await the ultimate satisfaction of Matt Scuder finally facing off against our two psychopathic killers, and they are indeed psychopaths. These two are very wicked men, gathering sadistic pleasure from torturing their captive women. The two men are kept as unsettling ciphers; we don’t know much about them except they have an addiction to killing. It’s not about the hundreds of thousands they scam from the drug traffickers; it’s really about the thrill of the hunt. While I wish there was more depth, they were menacing enough. I was itchy with anticipation for them to get some comeuppance. I’ve read reviews indicating that our two remorseless killers are a gay couple; if this is true it’s kept very vague for interpretation. In the age of equality, it could be homophobic to declare, in absolutes, that psychopathic killers couldn’t also be gay or lesbian. That would be… wrong?

With two strong villains, you need a strong hero to bring them down, and Neeson fits the part like a natural. To be fair, the role is somewhat stock from a passing description: the loner former cop with the tragic past, a drinking problem, the gruff style, the over-the-hill age, the man trying to adapt to a new and changing world, sometimes not for the better. It’s a role that feels ripped from the tropes of crime thrillers, a world we’ve also become accustomed to seeing Neeson. The detective role is familiar but, like most within Frank’s film, it’s given more time to breath and a surprising degree of attention. This doesn’t come close to last year’s Prisoners in the realm of character work, but it’s still an above-average entry for a genre too often ignored when it comes to realistic and satisfying characterization. Matt Scudder exists in a New York City that owes a debt to the pulpy noir page-turners of old, but it’s not exactly stylized, and neither is he. The man still uses microfilm and needs the assistance of a street-smart homeless teenager to assist him with this newfangled Internet thing. While it feels somewhat forced, the relationship with Matt Scuder and his young protégée is the strongest in the film, opening up the character’s redemptive arc. It’s always appreciated to watch Neeson get to flex his acting muscles rather than just being given action choreography and trite tough guy bravado.

There’s one other actor I’d like to single out, and I’ll thank my mother for this. Fans of Downton Abbey (like dear old mom) may recall Dan Stevens as the dashing and departed Matt Crawley, but he is almost unrecognizable as the grieving husband/drug trafficker that kicks off our story. For one, the guy lost a decent amount of weight and his gaunt face makes him seem all the more mercurial and intense. The characters plays against type with our expectations for a drug dealer, and you may find yourself, like I did, warming to him and yearning for the man’s vengeance for his wife.

Frank’s direction is awash in the grime and seediness of New York City, with dark shadows washing over his troubled characters, and a sense of style that, while omnipresent in tone, doesn’t distract from the story. The rich cinematography by Mihai Malaimare Jr. (The Master, Tetro) is a great asset. The film noir elements are here in abundance and with due diligence. It rains in just about every scene. Why? All the better for a moody and eerier atmosphere, though the rain does actually factor into a character-based conflict for Matt’s protégée. It’s a moody thriller that is assuredly above average for its genre. Not everything quite works (the third act is too drawn out; a montage of AA 12 steps narration over sequences of violence is more than a little heavy-handed; the explicit Y2K setting doesn’t really have a purpose other than to limit certain technological advances not becoming of the genre) but Frank knows how to draw out the strengths of the genre.

Frank’s direction is awash in the grime and seediness of New York City, with dark shadows washing over his troubled characters, and a sense of style that, while omnipresent in tone, doesn’t distract from the story. The rich cinematography by Mihai Malaimare Jr. (The Master, Tetro) is a great asset. The film noir elements are here in abundance and with due diligence. It rains in just about every scene. Why? All the better for a moody and eerier atmosphere, though the rain does actually factor into a character-based conflict for Matt’s protégée. It’s a moody thriller that is assuredly above average for its genre. Not everything quite works (the third act is too drawn out; a montage of AA 12 steps narration over sequences of violence is more than a little heavy-handed; the explicit Y2K setting doesn’t really have a purpose other than to limit certain technological advances not becoming of the genre) but Frank knows how to draw out the strengths of the genre.

A Walk Among the Tombstones is a gritty genre throwback, but what really jumped out to me was the hook of the premise. Neeson plays a man on the outer edges of the law but a man who still bends toward the justice system he once worked for. What makes this character unique, or at least the promise of, is that he ends up becoming the private detective for the criminal world, and that I find to be fascinating. We think of criminals, especially drug traffickers, are tough men who can handle their own problems with extreme authority. But they are also just people and can get in over their head as well, and when they need someone with private eye skills, who knows how to operate inside the bounds of the law and out of them, that’s where Neeson comes in. He does such a good job that he gets recommended around the New York ring of drug traffickers. He’s like a Michael Clayton-style fix-it guy but for the criminal underworld, and I think this concept it rife with juicy potential. Tombstones is based upon a series of books by Lawrence Block, so there could be further adventures, and I would welcome them, especially if the finished product is as entertaining as this first foray.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Raid 2 (2014)

Rare is the movie that I feel I don’t even need to go into great detail rather than just scream, in a fashion suiting madness, “See this! See it!” Such is the case for The Raid 2, the sequel to the 2012 Indonesian action film that melted faces with its inventive and brutal action. The original movie had a confined location, a gang-run tenement building, and a simple premise of reaching the top and nabbing the bad guy. When people weren’t punching or shooting each other, the original Raid lagged, but director/writer Gareth Evans has solved the problem with his action-packed sequel. The world expands greatly, establishing the uneasy peace kept by powerful and warring criminal organizations. The plot ends up becoming something akin to The Departed meets A Prophet, following our hero cop from the first movie now placed undercover to gain the trust of the criminal overlords and work his way up the food chain. When the action isn’t cooking, you’re still engaged with the story and the suspense simmers in clever ways. But getting back to the film’s calling card, the action sequences are impeccably choreographed and edited, have a wide variety of locations for fun, and are bloody intoxicating. This is a movie soaked in adrenaline, and the action sequences will be hard to beat for the rest of the year. Evans finds ways to provide flair for his supporting characters, including a family duo that involves a deaf woman whose weapon of choice is hammers and a guy who prefers a baseball and a bat. The Raid 2 fires on all cylinders so well, so brilliantly filmed, that it puts just about every American action thriller to shame. It doesn’t need to be as long as it is (pushing two and a half hours), and it takes a little while to set up the players, but this is even more of an entertaining rush than the original, because now we get a sense of what Evans and his team can do with fewer restrictions. When Evans gets to Hollywood, and he will, just make sure you give him all the money to do whatever he wants.

Rare is the movie that I feel I don’t even need to go into great detail rather than just scream, in a fashion suiting madness, “See this! See it!” Such is the case for The Raid 2, the sequel to the 2012 Indonesian action film that melted faces with its inventive and brutal action. The original movie had a confined location, a gang-run tenement building, and a simple premise of reaching the top and nabbing the bad guy. When people weren’t punching or shooting each other, the original Raid lagged, but director/writer Gareth Evans has solved the problem with his action-packed sequel. The world expands greatly, establishing the uneasy peace kept by powerful and warring criminal organizations. The plot ends up becoming something akin to The Departed meets A Prophet, following our hero cop from the first movie now placed undercover to gain the trust of the criminal overlords and work his way up the food chain. When the action isn’t cooking, you’re still engaged with the story and the suspense simmers in clever ways. But getting back to the film’s calling card, the action sequences are impeccably choreographed and edited, have a wide variety of locations for fun, and are bloody intoxicating. This is a movie soaked in adrenaline, and the action sequences will be hard to beat for the rest of the year. Evans finds ways to provide flair for his supporting characters, including a family duo that involves a deaf woman whose weapon of choice is hammers and a guy who prefers a baseball and a bat. The Raid 2 fires on all cylinders so well, so brilliantly filmed, that it puts just about every American action thriller to shame. It doesn’t need to be as long as it is (pushing two and a half hours), and it takes a little while to set up the players, but this is even more of an entertaining rush than the original, because now we get a sense of what Evans and his team can do with fewer restrictions. When Evans gets to Hollywood, and he will, just make sure you give him all the money to do whatever he wants.

Nate’s Grade: A-

The Place Beyond the Pines (2013)

Ambitious filmmaking is welcome, but usually ambition leads somewhere, which is the main problem with co-writer and director Derek Cianfrance’s unwieldy 140-minute multi-generational crime drama, The Place Beyond the Pines. First we watch Luke (Ryan Gosling) as a traveling motorcyclist enter a life of crime to support his infant son. Next the focus shifts to Avery (Bradley Cooper) as a cop with a conscience running into corruption on the force. Last, we jump ahead into the future and watch the dramatic irony unfold as the children of Avery and Luke interact, waiting for them to learn their paternal connection. I believe Cianfrance (Blue Valentine) and his team was attempting to tell a meditative, searching drama about children paying for the sins of their fathers, the lingering fallout of bad decisions and moral compromises. Except that’s not this film. By the end of the movie, while some secrets have been laid bare, there really aren’t any significant consequences. The film does an excellent job of maintaining a sense of dread, but it doesn’t come to anything larger or thought provoking. The entire structure of this film is geared toward a tragic accumulation, but it just doesn’t materialize. That’s a shame because it’s got great acting through and through, though I have grown weary of Gosling’s taciturn antihero routine that seems like a rut now. Avery’s portion of the plot was the most interesting and anxiety-inducing, but I found the movie interesting at every turn. The characters are given pockets of nuance and ambiguity as they traverse similar paths of desperation and conciliation. The Place Beyond the Pines is a perfectly good movie, albeit disjointed, that cannot amount to the larger thematic impact it yearns for.

Ambitious filmmaking is welcome, but usually ambition leads somewhere, which is the main problem with co-writer and director Derek Cianfrance’s unwieldy 140-minute multi-generational crime drama, The Place Beyond the Pines. First we watch Luke (Ryan Gosling) as a traveling motorcyclist enter a life of crime to support his infant son. Next the focus shifts to Avery (Bradley Cooper) as a cop with a conscience running into corruption on the force. Last, we jump ahead into the future and watch the dramatic irony unfold as the children of Avery and Luke interact, waiting for them to learn their paternal connection. I believe Cianfrance (Blue Valentine) and his team was attempting to tell a meditative, searching drama about children paying for the sins of their fathers, the lingering fallout of bad decisions and moral compromises. Except that’s not this film. By the end of the movie, while some secrets have been laid bare, there really aren’t any significant consequences. The film does an excellent job of maintaining a sense of dread, but it doesn’t come to anything larger or thought provoking. The entire structure of this film is geared toward a tragic accumulation, but it just doesn’t materialize. That’s a shame because it’s got great acting through and through, though I have grown weary of Gosling’s taciturn antihero routine that seems like a rut now. Avery’s portion of the plot was the most interesting and anxiety-inducing, but I found the movie interesting at every turn. The characters are given pockets of nuance and ambiguity as they traverse similar paths of desperation and conciliation. The Place Beyond the Pines is a perfectly good movie, albeit disjointed, that cannot amount to the larger thematic impact it yearns for.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Prisoners (2013)

One rainy Thanksgiving day, two little girls go missing. Keller and Grace Dover (Hugh Jackman, Maria Bello) and their neighbors, Franklin and Nancy Birch (Terrence Howard, Viola Davis), discover their two young daughters have gone missing. A manhunt is underway for a suspicious RV, spearheaded by Detective Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal). The RV is found with Alex Jones (Paul Dano) inside. The problem is that there is no physical evidence of the missing girls inside the RV and Alex has the mental capacity of a ten-year-old. He’s being released and Keller is incensed. He’s certain that Alex is guilty and knows where his missing daughter is being held. One night, Keller kidnaps Alex and imprisons him in an abandoned building. He beats him bloody, demanding Alex to tell him the truth, but he only remains silent. Loki has to deal with finding the girls, finding a missing Alex, and trailing Keller, suspicious of foul play.

One rainy Thanksgiving day, two little girls go missing. Keller and Grace Dover (Hugh Jackman, Maria Bello) and their neighbors, Franklin and Nancy Birch (Terrence Howard, Viola Davis), discover their two young daughters have gone missing. A manhunt is underway for a suspicious RV, spearheaded by Detective Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal). The RV is found with Alex Jones (Paul Dano) inside. The problem is that there is no physical evidence of the missing girls inside the RV and Alex has the mental capacity of a ten-year-old. He’s being released and Keller is incensed. He’s certain that Alex is guilty and knows where his missing daughter is being held. One night, Keller kidnaps Alex and imprisons him in an abandoned building. He beats him bloody, demanding Alex to tell him the truth, but he only remains silent. Loki has to deal with finding the girls, finding a missing Alex, and trailing Keller, suspicious of foul play.

This is a movie that grabs you early and knows how to keep you squirming in the best ways. The anxiety of a missing child is presented in a steady wave of escalating panic. The moment when you watch the Dover and Birch families slowly realize the reality of their plight, well it’s a moment that puts a knot in your stomach. Prisoners is filled with moments like this, that make you dread what is to come next. The crime procedural elements of the case are generally interesting and well handled to the point that they feel grounded, that these events could transpire, including police mistakes. The central mystery sucks you in right away and writer Aaron Guzikowski (Contraband) lays out clues and suspects with expert pacing, giving an audience something new to think over. At 153 minutes, there is a lot to chew over in terms of plot developments and character complications. It’s a compelling mystery yarn and shows such promise, though the last half hour cannot deliver fully. Fortunately, Prisoners is packed with terrific characters, a real foreboding sense of Fincher-esque chilly atmosphere from director Denis Villeneuve (Incendies) and greatest living cinematographer Roger Deakens (Skyfall). The film’s overall oppressive darkness is also notable for a mainstream release. The darkness doesn’t really let up. It’s hard to walk out feeling upbeat but you’ll be thankful for those punishing predicaments.

By introducing the vigilante torture angle, Prisoners is given a dual storyline of suspense and intrigue. How far will Keller go? Will he get caught? What will his friends think? Will they be supportive or will they crack? How does this change Keller? That last question is the most interesting one. Others tell us how Keller is a good man, and he’s certainly a devoted family man, but does a good man imprison and torture a mentally challenged man? Does a good man take the law into his own hands? If it meant the difference between your child being dead or alive, how far would you go? These are the questions that bubble up and the movie makes you deal with them. The torture segments are unflinching and challenge your viewer loyalty. You will be placed in an uncomfortable moral position. Then there’s just the what-would-you-do aspect of the proceedings. Could you torture someone, possibly to death? Fortunately most of us will never have to find out. I do wish, however, that the movie had gone further, complicating matters even more severely. It becomes fairly evident halfway through that Alex is innocent. It would have been even more interesting to intensify Keller’s legal troubles. If the police have their man, what does Keller do with Alex? Does he let him live after everything Keller has done? I think it would have worked as a logical escalation and put the audience in an even more uncomfortable position, forcing us to question whether Keller deserves to get away with what he did or pay a price.

By introducing the vigilante torture angle, Prisoners is given a dual storyline of suspense and intrigue. How far will Keller go? Will he get caught? What will his friends think? Will they be supportive or will they crack? How does this change Keller? That last question is the most interesting one. Others tell us how Keller is a good man, and he’s certainly a devoted family man, but does a good man imprison and torture a mentally challenged man? Does a good man take the law into his own hands? If it meant the difference between your child being dead or alive, how far would you go? These are the questions that bubble up and the movie makes you deal with them. The torture segments are unflinching and challenge your viewer loyalty. You will be placed in an uncomfortable moral position. Then there’s just the what-would-you-do aspect of the proceedings. Could you torture someone, possibly to death? Fortunately most of us will never have to find out. I do wish, however, that the movie had gone further, complicating matters even more severely. It becomes fairly evident halfway through that Alex is innocent. It would have been even more interesting to intensify Keller’s legal troubles. If the police have their man, what does Keller do with Alex? Does he let him live after everything Keller has done? I think it would have worked as a logical escalation and put the audience in an even more uncomfortable position, forcing us to question whether Keller deserves to get away with what he did or pay a price.

What separates Prisoners from other common thrillers, and what must have appealed to such an all-star cast, is the raised level of characterization on display. Jackman’s (Les Miserables) intensity is searing, as is his character’s sense of pain and futility. By all accounts, this is the best acting work Jackman has done in his career. Keller’s determination is all consuming, pushing away his doubts with his reliable pool of anger. Everyone is failing him so he feels he must take matters into his own hands, and the film does a fine job of relating his frustrations and urgency. But Keller is also in danger of derailing the ongoing investigation, becoming a liability to finding his daughter. This predicament pushes Loki into the tricky role of having to defuse parental intrusion, pushing him into a role he loathes, having to tell a harrowed father to back off. Loki is also consumed with the case, causing plenty of internal tumult and chaffing with the inefficiency and miscommunication of the police force. Gyllenhaal (End of Watch) doesn’t play his character big; he keeps it at a simmer, with hints of rage below the surface. His character is certainly richer than the Driven Cop we’ve often seen. His character is given less moral ambiguity but you feel his frustration working within the system and hitting dead ends. These two performers are both ticking time bombs.

The rest of the supporting cast has a moment or two to shine, though the characters are given less to work with. Bello (Grown Ups 2) is hastily disposed of from a plot standpoint by making her practically comatose with grief. Davis (The Help) knows how to make the most of limited screen time (see her Oscar nominated performance in 2008’s Doubt as evidence), and she’s heartbreaking in her moments of desperate pleading. Howard (Lee Daniels’ The Butler) is meant as the foil to Keller, a voice of moral opposition, but Howard lets the gravity of his involvement in horrible acts hit you hard. Dano (Ruby Sparks) has the toughest part in many ways because of his character’s brokenness and the fact that he’s being tortured so frequently. It’s hard not to sympathize with him even if part of you suspects his guilt. Naturally, Dano is adept at playing weirdos. Melissa Leo (Olympus Has Fallen) is nearly unrecognizable as Alex’s older aunt caring for him. She’s prepared for the worst from the public but has some nice one-on-ones where she opens up about the difficulty of losing a child herself.

Prisoners is such a good mystery that it works itself into a corner to maintain it, ensuring that no real answer or final reveal will be satisfying, and it isn’t. I’m going to tiptoe around major spoilers but I will be delving into some specifics, so if you wish to remain pure, skip ahead. The culprit behind the child abductions, to put it mildly, is underwhelming and rather obtuse in their wicked motivation. The specified reason is to test people’s faith and turn them into monsters by abducting their children. This comes across as an awfully nebulous philosophical impetus, and it’s a motivating force that I find hard to believe even in the grimy, dark reality the movie presents. It just doesn’t feel grounded, more like a last-ditch conclusion to a TV procedural. However, what makes this ending worse is the false turns and red herrings that Prisoners utilizes. Every mystery requires some red herrings but they need to seem credible, and if executed properly, the characters will learn something useful through the false detour. The issue with Prisoners is that it establishes a secondary suspect that is so OBVIOUSLY the guilty guy, compounded with plenty of incriminating evidence including the missing children’s clothing covered in blood. When this suspect comes undone, his sketchy behavior starts to become a series of contrivances. They introduce a character that is too readily the guilty party, and then they just as easily undo him. And here’s another character of questionable motivation. Plus, there’s the central contrivance of having two characters that remain mute under all torturous circumstances unless the plot requires them to say something that can only be interpreted in an incriminating manner. These mounting plot contrivances, and an ending that wants to be ambiguous but in no way is, rob Prisoners of being the expertly crafted thriller it wants to be. It still hits you in the gut, but you’ll be picking it apart on the car ride home.

Prisoners is such a good mystery that it works itself into a corner to maintain it, ensuring that no real answer or final reveal will be satisfying, and it isn’t. I’m going to tiptoe around major spoilers but I will be delving into some specifics, so if you wish to remain pure, skip ahead. The culprit behind the child abductions, to put it mildly, is underwhelming and rather obtuse in their wicked motivation. The specified reason is to test people’s faith and turn them into monsters by abducting their children. This comes across as an awfully nebulous philosophical impetus, and it’s a motivating force that I find hard to believe even in the grimy, dark reality the movie presents. It just doesn’t feel grounded, more like a last-ditch conclusion to a TV procedural. However, what makes this ending worse is the false turns and red herrings that Prisoners utilizes. Every mystery requires some red herrings but they need to seem credible, and if executed properly, the characters will learn something useful through the false detour. The issue with Prisoners is that it establishes a secondary suspect that is so OBVIOUSLY the guilty guy, compounded with plenty of incriminating evidence including the missing children’s clothing covered in blood. When this suspect comes undone, his sketchy behavior starts to become a series of contrivances. They introduce a character that is too readily the guilty party, and then they just as easily undo him. And here’s another character of questionable motivation. Plus, there’s the central contrivance of having two characters that remain mute under all torturous circumstances unless the plot requires them to say something that can only be interpreted in an incriminating manner. These mounting plot contrivances, and an ending that wants to be ambiguous but in no way is, rob Prisoners of being the expertly crafted thriller it wants to be. It still hits you in the gut, but you’ll be picking it apart on the car ride home.

Grisly, morally uncomfortable, and genuinely gripping, Prisoners is a grownup thriller that isn’t afraid to go to dark places, with its characters and its plot. It hooks you early and keeps you on the hook, pushing its characters to make desperate decisions and asking you to think how you would perform under similar pressure. It’s a fascinating meta game and one that also adds extra intrigue to a rather intriguing mystery. It may not be revolutionary, but Prisoners is an above-average thriller with strong suspense and characterization. Where Prisoners stumbles is how it brings all this darkness to a close. The ending is rather perfunctory and not terribly satisfying; perhaps no ending would have been truly satisfying given the setup, but I’d at least prefer an alternative to the one I got, especially since it feels less grounded than the 140 minutes or so beforehand. It’s an ending that doesn’t derail the movie, but it certainly blunts the film’s power and fulfillment. Then again perhaps a word like “fulfillment” is the wrong term to use on a movie that trades in vigilante torture and the cyclical nature of abuse. In pursuit of perceived justice, what are we all capable of doing? The answer is likely surprising and disheartening for many, and Prisoners deserves credit for pushing its audience into uncomfortable positions and reflections.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Heat (2013)

Essentially a buddy cop movie with the typically macho roles swapped out to women, The Heat is an intermittently enjoyable action comedy thanks to the chemistry between Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy. The joke ratio of hits to misses has a lot of whiffs but I laughed solidly every ten minutes or so, some of the comedic set pieces were well developed, and McCarthy’s strong ability to improv saved many flailing scenes. I enjoyed that these two women were seen as professionals and didn’t need to be bogged down with the kind of plot elements you’d find in your standard Katherine Heigl vehicle. There isn’t a romantic interest nor a love story; in fact, various guys come up to McCarthy throughout asking why she hadn’t called them back after a one-night stand. It’s a little thing but it establishes that a woman like McCarthy’s can have a fruitful love life and have it be no big deal. The overall plot about a dangerous drug baron with a mole inside the government is given more complexity than necessary, and I’m not sure the action bits feel well integrated into the movie as a whole. Part of this may just be because director Paul Feig (Bridesmaids) seems much more interested in grounded, human comedy, but I think it’s mostly because we’d rather be spending more time with our leads arguing. Bullock and McCarthy are an engaging team, their comedic styles nicely ping-ponging off one another, and there are enough ribald gags to justify watching it. The Heat isn’t revolutionary by any sort but maybe, in the end, that’s the point. Also it’s got Dan Bakkeddahl (TV’s Veep) as an albino DEA agent. So there’s that too.

Essentially a buddy cop movie with the typically macho roles swapped out to women, The Heat is an intermittently enjoyable action comedy thanks to the chemistry between Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy. The joke ratio of hits to misses has a lot of whiffs but I laughed solidly every ten minutes or so, some of the comedic set pieces were well developed, and McCarthy’s strong ability to improv saved many flailing scenes. I enjoyed that these two women were seen as professionals and didn’t need to be bogged down with the kind of plot elements you’d find in your standard Katherine Heigl vehicle. There isn’t a romantic interest nor a love story; in fact, various guys come up to McCarthy throughout asking why she hadn’t called them back after a one-night stand. It’s a little thing but it establishes that a woman like McCarthy’s can have a fruitful love life and have it be no big deal. The overall plot about a dangerous drug baron with a mole inside the government is given more complexity than necessary, and I’m not sure the action bits feel well integrated into the movie as a whole. Part of this may just be because director Paul Feig (Bridesmaids) seems much more interested in grounded, human comedy, but I think it’s mostly because we’d rather be spending more time with our leads arguing. Bullock and McCarthy are an engaging team, their comedic styles nicely ping-ponging off one another, and there are enough ribald gags to justify watching it. The Heat isn’t revolutionary by any sort but maybe, in the end, that’s the point. Also it’s got Dan Bakkeddahl (TV’s Veep) as an albino DEA agent. So there’s that too.

Nate’s Grade: C+

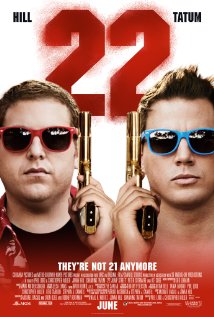

When 21 Jump Street was proposed as a movie, nobody thought it was a good idea. Even its stars and writers. They used that as an opportunity to craft one of the more charming, surprising, and hilarious films of 2012, a movie so good that it was also one of the best films of a relatively great year at the movies. Now that was something nobody expected with a 21 Jump Street movie. As often happens, Hollywood looks to keep the good times going, and 22 Jump Street is knocking at the door. In Hollywood tradition, sequels usually follow the “more of the same” format with a dash of “bigger is better,” a fact that 22 Jump Street takes to heart.

When 21 Jump Street was proposed as a movie, nobody thought it was a good idea. Even its stars and writers. They used that as an opportunity to craft one of the more charming, surprising, and hilarious films of 2012, a movie so good that it was also one of the best films of a relatively great year at the movies. Now that was something nobody expected with a 21 Jump Street movie. As often happens, Hollywood looks to keep the good times going, and 22 Jump Street is knocking at the door. In Hollywood tradition, sequels usually follow the “more of the same” format with a dash of “bigger is better,” a fact that 22 Jump Street takes to heart.

You must be logged in to post a comment.