Blog Archives

Reagan (2024)

My seventy-five-year-old father doesn’t get out to see as many movies as he used to, but one he was dead-set on seeing in theaters was Reagan. My sister took him and he came back singing the movie’s praises, celebrating Dennis Quaid’s portrayal of the 40th president of the U.S. of A. and extolling the virtues of this trip down Boomer memory lane. I’m glad my father enjoyed the movie. I’m glad the filmmakers could provide him two hours of uplift and entertainment, especially during times like these where my whole family can use the escape from present-day worries. I’m also retroactively relieved that I didn’t see the movie with him, though as a dutiful son and his movie buddy for decades, I would have. I’m glad because our opinions on the overall artistic merits would have been significantly different, and I wouldn’t want to rain on my father’s personal enjoyment (that’s what the written word is for).

For the benefit of analyzing Reagan as a movie first and foremost, I’ll reserve my reservations about his political legacy for the end of the review, but even as a standard presidential biography, Reagan the movie is a disappointing and reductive trip through one man’s Wikipedia summation of a career. I’ve become much more a fan of the biographies that choose a seminal moment from a public figure’s life to use as a framing device for the larger legacy (think 2012’s Lincoln focusing on the passage of the thirteenth amendment). I’d prefer that approach to the more familiar cradle-to-grave structure that often feels like a zoom through their greatest hits where none of the events are granted the consideration or nuance deserved. With Reagan the movie, we’re sprinting through history, although Reagan doesn’t even become president until an hour in. Instead, the focus is unilaterally on Reagan’s opposition to communism and the Soviets. Obviously distilling eight years of a presidency into a couple hours is a daunting and improbable task, the same difficulty for distilling any person’s complicated life into an accessible two hours of narrative. Still, you should have expected more.

For those coming into the movie looking for a critical eye, or an even-handed approach to this man’s faults and accomplishments, the movie condenses itself into a narrow examination on communism and the Cold War, a story we already know proves triumphant. The cumulative problem with Reagan the movie is that it doesn’t really add to a deeper understanding of the man. With its streamlined narrative and pacing, the movie sticks to its Greatest Hits of Reagan, especially his speeches. There are several famous Reagan speeches littered throughout the last act of the movie, and it doesn’t do much for a better understanding of the man delivering those remarks as just hitting upon people’s memories of the man in public venues. It would be more insightful to watch the team behind the scenes debating their choices. The movie portrays Reagan the man more like Saint Regan, arguing if there are any presentable faults they should be readily forgiven because it was all in pursuit of morally impregnable goals (he remarks that the vicious right-wing contras remind him of George Washington and the early colonial army…. yeah, sure). The filmmakers are too afraid to say anything too critical but also to reveal anything truly revelatory about their subject. So the movie becomes a glossy nostalgic-heavy drama without much in the way of drama because Reagan will always persevere through whatever hardships thanks to the power of his convictions, which will always be proven right no matter the context and repercussions. The movie seems to imply all his decisions led to the fall of the Berlin Wall, so it all must have worked out, right? Well, not for everybody, movie, but we’ll get to that in due time.

The filmmakers elect to frame the movie through a curious narrator – a retired KGB officer (Jon Voight) that has followed the life and times of Ronald Reagan going back to his early days. Apparently, this Soviet spy saw true greatness in Reagan way back and thought he might become a threat to the continuation of communism. It’s a strange perspective to be locked into, the enemy complimenting Reagan from afar and ultimately crediting the man’s faith in God as the reason that America triumphed over the Soviets. It means then that every scene has to be linked to our KGB narrator, and sometimes that can get questionable, like when he’s talking about Reagan’s time as a teenage lifeguard, or the time Reagan was being bullied by local kids, or Regan’s intimate conversations with his first wife, Jane Wyman (Mena Suvari). The scenes in Hollywood are so clunky, especially a dinner where the movie wants us to look down on Dalton Trumbo, blacklisted Hollywood Ten writer. This man stood for his principles and suffered a real backlash, and you want me to think of him as misguided and part of some liberal communist cabal (the movie also includes a picture of Oppenheimer as part of its Soviet influence targets)? By insisting upon a narrator that’s not Reagan, that means this KGB spy it also means that we’re seeing the world of Ronald Reagan through an interpreter’s prism, which makes the scenes even more curious for being such an unexpected cheerleader over Reagan’s amazing instincts and abilities. It would be like having Stalin narrate a biopic about FDR and showering the president with gushing praise.

Limiting the movie’s focus to Reagan’s lifelong battle against communist forces makes for a much cleaner and more triumphant narrative, and also leads to an ending we all know is coming, not that surprise or nuance is what the primary audience is looking for. The movie posits that Reagan pursued becoming the country’s chief executive for the selfless mission of standing up to the nefarious forces of communism. Then again, in the opening moments, the movie also tacitly implies that maybe it was the Russians who shot him back in 1981 when it was really an incel who thought he might impress Jodie Foster. Those opening moments also present a cliffhanger to come back to, as if there’s a gullible portion of the audience that is hanging on pins and needles in anticipation whether or not Reagan really was killed back in 1981 (“But… but if Ronnie dies, then who was left to beat the commies?”). It’s a very selective narrative framing that makes the movie easy to celebrate because Reagan is presented as America’s steadfast defender who stood up for our apple-pie American values and brought down the Soviets. Reagan certainly played his part in helping to facilitate the collapse of the Soviet Union, but he was one man coming in at the end of a chain of events spanning decades. I liken it to having a group project in school where you and your cohorts work steadily all week, and then the day it’s due, a kid who’s been absent all week except for that day comes onto the project, adds some contributions, and then takes credit for everything accomplished. Reagan gets his due but so do the other U.S, presidents, secretaries of state, and lots and lots of ambassadors that also helped reach this monumental conclusion. However, the biggest contributor to the collapse of the Soviet Union belongs to the Soviets themselves and their rejection of living in a reality in conflict with the dogma of their political leaders (sound familiar to anyone?).

The screenwriters also position the Great Communicator as being so powerfully persuasive that all it took was one speech and everyone was left helplessly in thrall of this man’s honeyed words. It takes on such a grandiose scale that makes Reagan look like a superhuman. The movie sets up its climax over whether or not Reagan will say “tear down this wall” in a speech at the Brandenburg Gate in 1987, which heightens the drama to a level of self-parody. Is there any spectator wondering if Reagan will eventually say the words that became famous? Beyond the false drama of whether or not Reagan will utter this phrase, the movie tries to fashion some unconvincing behind-the-scenes hand-wringing over what it will mean if Reagan says these words while in Germany. As if the man has ever been shy about denouncing communism and the Soviet state beforehand. The movie also exists in a world where every world leader and responsible adult is glued to a TV set watching Reagan speechify at any key moment. Hilariously, after Reagan does indeed say “tear down this wall,” the film cuts to Margaret Thatcher watching and solemnly saying, “Well done, cowboy.” The rousing music reaches a crescendo, the Reagan team celebrates like they just landed a man on the moon, and the implication is that now that Reagan has put these four words together in sequence, well that Gorbachev fella has no choice now. The movie is set up like this speech is the final blow that pushes the Soviet Union into the dustbin of history. And yet, the next scene of the Berlin Wall coming down has a helpful on-screen designation of time: “two years later.” So Ronnie gave his amazing speech and it immediately led to the end of East Germany… two years later. Does George H. W. Bush get all the credit for being president when the Soviet Union actually collapsed in 1991? I’m sure we can find a speech somewhere where he said something bad about them, and if Reagan the movie is an indication about political persuasion, all he had to do was say the words out loud. Then the wicked communist curse is broken, but few people knew that, only those who worked for Ronnie.

The movie goes to this magical solution time and again, as Reagan is able to solve any crisis with just the right combination of words. Whether it’s Vietnam protestors he cows into retreat by shushing them, or even a debate where all he has to do is throw out a joke and the opposition must crumble because nobody can recover in the face of a joke; the movie presents time and again a silly and reductive version of politics where all it takes is for people to hear the cherished words of Saint Reagan and be converted. Look, Reagan was an influential figure and inspired a generation of Republican leaders to follow in his wake, and yes his telegenic skills were an asset to his understanding of how to handle issue framing. But to reduce everything down to his overwhelming oratory powers of persuasion makes it seem like everyone in the world is falling prey to a linguistic cheat code they are unaware of. It’s the kind of deification that we might see in a North Korean movie extolling the powers of Kim Jong-Un (“He golfed a hole-in-one with every hole”). This is what a hagiography does rather than an honest biography, and that is why Reagan becomes a relatively useless dramatic enterprise except for those already predisposed to wanting to have their nostalgia tickled and their worldviews safely confirmed.

I wasn’t exactly expecting, say, an even-handed review over Reagan’s legacy, but there’s something rather incendiary about how it distills all of the opposition to Reagan and his policies. Our KGB narrator intones that not everybody was a fan of good ole Ronnie, and then in an abbreviated montage we get real news footage of protestors with placards condemning the Reagan administration for ignoring the AIDS epidemic, for tax cuts for the rich, for supporting the apartheid government of South Africa, for gutting social safety net programs, etc. The handling of the Iran-Contra scandal is hilariously sidestepped by the same Reagan who is shown on screen being so dogmatic about sticking to law that he fired all the striking air traffic control workers. It’s not enough that the movie reduces all relevant critical opposition to Reagan to a brief music montage, it’s that the movie then quickly transitions directly to a map of the 1984 electorate with Reagan winning in a landslide, as if to say, “Well, these cranky dead-enders sure were upset by these issues, but they must be wrong because the American people overwhelmingly re-elected him.”

I never found Quaid’s performance to be enlightening or endearing, more mimicry that settles into an unsettling cracked-mirror version. It always felt like an imitation for me, like something I’d see on Saturday Night Live in the 1980s with Phil Hartman. He holds the grin and nasally voice but delivers little pathos. It’s not exactly the actor’s fault when the screenplay gives him such little to do. There was a real opportunity to better humanize him toward the end as his mental decline was becoming more of a force. Instead, it’s relegated to the very end, as a gauzy way to usher the man off the stage with our sympathies. Voight (Ray Donovan) gets the most lines in the whole movie and really seems to savor his Ruskie accent. Curiously, his character is talking to a promising KGB pupil trying to learn where they went wrong and it’s not set up to be Vladamir Putin, himself a former KGB agent. The only other significant supporting role that lasts is Nancy Reagan played by Penelope Ann Miller (The Shadow, Carlito’s Way) and she’s relegated to the suffering spouse on the sidelines that always has the steel spine and the word of encouragement. Her best moment of acting was her embarrassment as a captive witness to Ronnie, before his step into politics, awkwardly dancing on stage with the PBR players as a shill for the beer company.

Let’s be honest about who Reagan is aimed at, an older, mostly conservative audience looking back at the time of Reagan’s reign and thinking, “Those were the good old days.” It’s not made for people like me, a progressive who legitimately believes that many of our modern-day problems can trace their source from the eight years of the Reagan administration. I’m talking about the trickle-down-economic fallacy that girds so much Republican magical thinking when it comes to taxes. I’m talking union busting, I’m talking his “welfare queen” projection, I’m talking the selling of arms for hostages (bonus fact: the Reagan campaign was secretly negotiating with Iran not to release the hostages until after the election to better doom Jimmy Carter’s chances of re-election), I’m talking about making college education far more expensive by massive cuts to state funding, I’m talking the rise of the disingenuous “textualist” judicial philosophy that only seems to mean something when its proponents want it to, I’m talking about training and arming Osama bin Laden to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan (wonder why the movie chose not to include this since it is Reagan fighting communism), and so on and so on. Naturally none of these are held to scrutiny by Reagan the movie because it’s from the writer of God’s Not Dead and the director of Bratz.

Suffice to say, Reagan has many notable shortcomings depicting a president who, with every passing year, only seems to add to his own shortcomings in legacy (the Party of Reagan has willfully given up all its purported principles to become the Party of Trump). If you’re looking for an overly gauzy, sentimental, and simplistic retelling of what people already know about Ronald Reagan, then this movie is for you. If you’re looking for anything more, then this is the New Coke of presidential biopics.

Nate’s Grade: C-

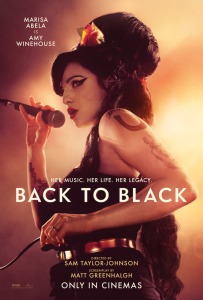

Back to Black (2024)

What do you remember about Amy Winehouse? The tragic singer with the booming voice that was mercilessly picked apart by a rabid tabloid media, as well as rampant online speculation, over every step of her addiction to drugs and alcohol? If that’s the extent of your memory, as well as some of her more notable songs like “Rehab” or “Back to Black,” then this musical biopic directed by Sam Taylor-Johnson (Fifty Shades of Grey, Nowhere Boy) is going to feel like a shallow exercise in piling on a troubled and talented performer gone far too soon.

What do you remember about Amy Winehouse? The tragic singer with the booming voice that was mercilessly picked apart by a rabid tabloid media, as well as rampant online speculation, over every step of her addiction to drugs and alcohol? If that’s the extent of your memory, as well as some of her more notable songs like “Rehab” or “Back to Black,” then this musical biopic directed by Sam Taylor-Johnson (Fifty Shades of Grey, Nowhere Boy) is going to feel like a shallow exercise in piling on a troubled and talented performer gone far too soon.

Back to Black, the film, literally has Amy Winehouse (Marisa Abela) vocalize what she wants to be remembered for, not the drugs and alcohol, and the movie then erases Amy as a vibrant, complicated human being into a blurred statistic on the dangers of unchecked addiction. You can’t tell her story without documenting her demons, and yet the movie also seems exceptionally forgiving to the men who contributed to her downfall, her doting father Mitch (Eddie Marsan) who enabled her and her bad boy boyfriend Blake (Jack O’Connell) who introduced her to hard drug abuse. We spend so much emphasis on the bad times and her downfall and yet the movie is strangely reticent to cast much judgment on her bad influences, which makes it seem like the movie is further blaming Amy. At the same time, her downfall is focused on being rejected by a man, which is really insulting and limiting for her as an artist as well as a person capable of independent thought. It’s an even stranger decision given that these two influences, her father and ex, were given withering condemnation in the 2015 Oscar-nominated documentary on Winehouse. Apparently, Mitch Winehouse was furious with the documentary’s portrayal of him and Amy. His secondary complaint was that the documentary focused too much on the negative aspects of her life story, which is comical considering the skewed balance that Back to Black dwells upon. We speed through the good times to wallow in the bad, and without a stronger and more complex portrayal of Amy as a character, it all feels trashy and degrading. It’s harder to feel the heartbreak when the movie is only defining her by our foreknowledge of her death.

Amy never feels like her own person in this movie, which is a shame since she was a dominant presence. We never get into her creative process or her inspirations. We never get to see the person behind the omnipresent tabloid headlines. The formulaic rise-and-fall structure is so rushed and uninterested in fleshing out Amy as a person, so we get simplistic impressions like she sure loved her “nan” (Leslie Manville) and never recovered from her death. The movie sets a midpoint montage where her grandma’s funeral pushes her to get a signature tattoo and beehive hairdo, and it plays like a superhero finally donning their cape and cowl (At last, she has become… Batman, I mean… the Amy We Remember). It’s played so dramatically that it might even unleash a titter or two. There is such scant insight into this woman and her demons that I doubt anyone will come away with a better understanding of Amy and her place in music history, as well as who she was as a person. The movie omits other struggles that might take the focus off its specific topic of drugs and alcohol. Her bulimia gets nary a mention except for maybe one scene where her inconsiderate roommate asks Amy to please vomit into the toilet a little less loudly. While skipping judgment over her enablers, the movie also avoids being too judgemental on the social impulses and rubbernecking that fed upon the harassment and mockery of Winehouse and her struggles. Again, by omission this is placing further blame onto Amy herself.

Amy never feels like her own person in this movie, which is a shame since she was a dominant presence. We never get into her creative process or her inspirations. We never get to see the person behind the omnipresent tabloid headlines. The formulaic rise-and-fall structure is so rushed and uninterested in fleshing out Amy as a person, so we get simplistic impressions like she sure loved her “nan” (Leslie Manville) and never recovered from her death. The movie sets a midpoint montage where her grandma’s funeral pushes her to get a signature tattoo and beehive hairdo, and it plays like a superhero finally donning their cape and cowl (At last, she has become… Batman, I mean… the Amy We Remember). It’s played so dramatically that it might even unleash a titter or two. There is such scant insight into this woman and her demons that I doubt anyone will come away with a better understanding of Amy and her place in music history, as well as who she was as a person. The movie omits other struggles that might take the focus off its specific topic of drugs and alcohol. Her bulimia gets nary a mention except for maybe one scene where her inconsiderate roommate asks Amy to please vomit into the toilet a little less loudly. While skipping judgment over her enablers, the movie also avoids being too judgemental on the social impulses and rubbernecking that fed upon the harassment and mockery of Winehouse and her struggles. Again, by omission this is placing further blame onto Amy herself.

For each viewer, Back to Black is going to sink or swim depending upon your reaction to Abela’s (Industry) performance. She does her own singing and learned to imitate Winehouse’s signature soaring vocals, so that’s generally impressive. However, I felt her greatest moments of acting were the scenes where she wasn’t in song. Her over-extended enunciation and head bobs made me consistently cringe, like watching an overzealous Vegas impersonator. In the few instances where the movie slows down, that is where Abela is best, being distraught over the loss of her nan, infuriated by her ex, incredulous at music producers that want to market Amy like the Spice Girls, and charmingly innocent confiding to a young fan in a checkout line. If the movie had cut all of her vocal performances and given me more time with this Amy Winehouse, I would have gotten more insight and entertainment. Abela isn’t given the material to really bring Amy to life.

Back to Black isn’t so much Amy’s movie as it is her father Mitch’s response to earlier portrayals. He’s portrayed here as a doting and loving father who only wanted what was best for her. You see, his initial refusal to the demands to send his daughter to rehab was because he wanted her to kick this whole addiction thing on her own. She didn’t want it so he wasn’t going to push her. If anything, he’s the hero of this movie, the proud papa who was let down by his daughter’s duplicitous boyfriend-turned-husband, the man who took his little girl away and turned her to the dark side of drugs. When you analyze the approach, it all comes across as a little insidious, a little icky, and unworthy of recreating this woman’s life experiences to better glorify her father. Abela gives it her all, it’s just too little to be had with Back to Black, a shallow biopic treading upon distaste. I’d recommend skipping this movie entirely, unless you’re irreversibly curious, and watch the 2015 documentary Amy instead. You’ll get a much better sense of Amy Winehouse the singer, the star, the addict, and most importantly, the complicated person.

Back to Black isn’t so much Amy’s movie as it is her father Mitch’s response to earlier portrayals. He’s portrayed here as a doting and loving father who only wanted what was best for her. You see, his initial refusal to the demands to send his daughter to rehab was because he wanted her to kick this whole addiction thing on her own. She didn’t want it so he wasn’t going to push her. If anything, he’s the hero of this movie, the proud papa who was let down by his daughter’s duplicitous boyfriend-turned-husband, the man who took his little girl away and turned her to the dark side of drugs. When you analyze the approach, it all comes across as a little insidious, a little icky, and unworthy of recreating this woman’s life experiences to better glorify her father. Abela gives it her all, it’s just too little to be had with Back to Black, a shallow biopic treading upon distaste. I’d recommend skipping this movie entirely, unless you’re irreversibly curious, and watch the 2015 documentary Amy instead. You’ll get a much better sense of Amy Winehouse the singer, the star, the addict, and most importantly, the complicated person.

Nate’s Grade: C

Oppenheimer (2023)

I finally did it. I watched all three hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one half of the biggest movie-going event of 2023, and arguably the most smarty-pants movie to ever gross a billion dollars. It was a critical darling all year long, sailed through its awards season, and racked up seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director for Nolan, a coronation for one of Hollywood’s biggest artists whose name alone is each new project’s biggest selling point. I’ve had friends falling over themselves with rapturous praise, and I’m sure you have too, dear reader, so the danger becomes raising your expectations to a level that no movie could ever meet. As I watched all 180 lugubrious minutes of this somber contemplation of man’s hubris, I kept thinking, “All right, this is good, but is it all-time-amazing good?” I can’t fully board the Oppenheimer hype train, and while I respect the movie and its exceptional artistry, I also question some of the key creative decision-making that made this movie exactly what it is, bladder-busting length and all.

I finally did it. I watched all three hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one half of the biggest movie-going event of 2023, and arguably the most smarty-pants movie to ever gross a billion dollars. It was a critical darling all year long, sailed through its awards season, and racked up seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director for Nolan, a coronation for one of Hollywood’s biggest artists whose name alone is each new project’s biggest selling point. I’ve had friends falling over themselves with rapturous praise, and I’m sure you have too, dear reader, so the danger becomes raising your expectations to a level that no movie could ever meet. As I watched all 180 lugubrious minutes of this somber contemplation of man’s hubris, I kept thinking, “All right, this is good, but is it all-time-amazing good?” I can’t fully board the Oppenheimer hype train, and while I respect the movie and its exceptional artistry, I also question some of the key creative decision-making that made this movie exactly what it is, bladder-busting length and all.

As per Nolan’s non-linear preferences, we’re bouncing back and forth between different timelines. The main story follows Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as an upstart theoretical physicist creating his own academic foothold and then being courted to join the Manhattan Project to beat the Nazis in the formation of a nuclear bomb. The other timeline concerns the Senate approval hearing for Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), the former head of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) with a checkered history with Oppenheimer after the war. A third timeline, serving as a connecting point, involves Oppenheimer undergoing a closed-door questioning over the approval of his security clearance, which brings to light his life of choices and conundrums.

If I was going to be my most glib, I would characterize Oppenheimer in summary as, “Man creates bomb. Man is then sad.” There’s much more to it, obviously, and Nolan is at his most giddy when he’s diving into the heavy minutia of how the project came about, the many brilliant minds working in tandem, and sometimes in conflict, to usher in a new era of science and energy. Of course it also has radical implications for the world outside of academic theory. The world will never be the same because of Oppenheimer dramatically upgrading man’s self-destructive power. The accessible cautionary tale reminds me of a Patton Oswalt stand-up line: “We’re science: all about ‘coulda,’ no about ‘shoulda.’” Oh the folly of man and how it endures.

If I was going to be my most glib, I would characterize Oppenheimer in summary as, “Man creates bomb. Man is then sad.” There’s much more to it, obviously, and Nolan is at his most giddy when he’s diving into the heavy minutia of how the project came about, the many brilliant minds working in tandem, and sometimes in conflict, to usher in a new era of science and energy. Of course it also has radical implications for the world outside of academic theory. The world will never be the same because of Oppenheimer dramatically upgrading man’s self-destructive power. The accessible cautionary tale reminds me of a Patton Oswalt stand-up line: “We’re science: all about ‘coulda,’ no about ‘shoulda.’” Oh the folly of man and how it endures.

For the first two hours, the focus is the secretive Manhattan Project out in the New Mexico desert and its myriad logistical challenges, all with the urgency of being in a race with the Nazis who already have a head start (their break is Hitler’s antisemitism pushing out brilliant Jewish minds). That urgency to beat Hitler is a key motivator that allows many of the more hand-wringing members to absolve those pesky worries; Oppenheimer says their mission is to create the bomb and not to determine who or when it is used. That’s true, but it’s also convenient moral relativism, essentially saying America needs to do bad things so that the Germans don’t do worse things, a line of adversarial thinking that hasn’t gone away, only the name of the next competitor adjusts. This portion of the movie works because it adopts a similarly streamlined focus of smart people working together against a tight deadline. Looking at it as a problem needing to surmount allows for an engaging ensemble drama complete with satisfying steps toward solutions and breakthroughs. It makes you root for the all-star team and excitedly follow different elements relating to nuclear fusion and fission that you would have had no real bearing before Nolan’s intellectual epic. For those two galloping hours, the movie plays almost like a brainy heist team trying to pull together the ultimate job.

It’s the time afterwards where Oppenheimer expands upon the lasting consequences where the movie finds its real meaning as well as loses me as a viewer. The legacy of the bomb is one that modern audiences are going to be readily familiar with 80 years after the events that precipitated their arrival, and they haven’t exactly been shelved or become the world war deterrent hoped for. As one of Oppenheimer’s physicists says, a big bomb only works until someone creates a bigger bomb, and then the arms race starts all over again fighting for incremental supremacy when it comes to whether one’s military might could destroy the world ten times or twelve times over. When Oppenheimer begins having reservations of what he has brought into this world is when his character starts becoming more dynamic, but it’s also too late. He can’t undo what he’s done, the world isn’t going back to a safer existence before nuclear arms, so his tears and fears come as short shrift. There’s a scene where Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), castigates him and says, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then make all of us to feel sorry for you when there are consequences.” Now this is in reference to a different personal failing of our protagonist, but the message resonates; however, I don’t know if this is Nolan’s grand takeaway. The movie in scope and ambition wants to set up this man as a tragic figure that gave birth to our modern world, but like President Truman says, it’s not about who created the bomb but who uses it. Oppenheimer is treated like a harbinger of regret, but I don’t think the story has enough to merit this examination, which is why Oppenheimer peters out after the bomb’s immediate aftermath.

It’s the time afterwards where Oppenheimer expands upon the lasting consequences where the movie finds its real meaning as well as loses me as a viewer. The legacy of the bomb is one that modern audiences are going to be readily familiar with 80 years after the events that precipitated their arrival, and they haven’t exactly been shelved or become the world war deterrent hoped for. As one of Oppenheimer’s physicists says, a big bomb only works until someone creates a bigger bomb, and then the arms race starts all over again fighting for incremental supremacy when it comes to whether one’s military might could destroy the world ten times or twelve times over. When Oppenheimer begins having reservations of what he has brought into this world is when his character starts becoming more dynamic, but it’s also too late. He can’t undo what he’s done, the world isn’t going back to a safer existence before nuclear arms, so his tears and fears come as short shrift. There’s a scene where Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), castigates him and says, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then make all of us to feel sorry for you when there are consequences.” Now this is in reference to a different personal failing of our protagonist, but the message resonates; however, I don’t know if this is Nolan’s grand takeaway. The movie in scope and ambition wants to set up this man as a tragic figure that gave birth to our modern world, but like President Truman says, it’s not about who created the bomb but who uses it. Oppenheimer is treated like a harbinger of regret, but I don’t think the story has enough to merit this examination, which is why Oppenheimer peters out after the bomb’s immediate aftermath.

It reminded me of an Oscar favorite from 2015, Adam McKay’s The Big Short, a true-ish account of real people profiting off the worldwide financial meltdown from 2008. It fools you into taking on the perspective of its main characters who present themselves as underdogs, keepers of a secret knowledge that they are trying to benefit from before an impending deadline. Likewise, the conclusion also makes you question whether you should have been rooting for this scheme all along since it was predicated on the economy crashing; these guys got their money but how many lives were irrevocably ruined to make their big score? With The Big Short, the movie-ness of its telling is part of McKay’s trickery, to ingratiate you in this clandestine financial world and to treat it like a heist or a con, and then to reckon whether you should have ever been rooting for such an adventure. Oppenheimer has a similar effect, lulling you with its admitted entertainment factor and beat-the-deadline structure. Once the mission is over, once the heroes have “won,” now the game doesn’t seem as fun or as justifiable. Except Oppenheimer could have achieved this effect with a judicious resolution rather than an entire third hour of movie shuffled throughout the other two like a mismatched deck of cards.

The last hour of the movie features a security clearance interrogation and a Senate confirmation hearing, neither of which have appealing stakes for an audience. After we watch the creation of a bomb, do we really care whether or not this one testy guy gets approved for a cabinet-level position or whether Oppenheimer might get his security clearance back? I understand that these stakes are meaningful for the characters, both essentially on trial for their lives and connections, but Nolan hasn’t made them as necessary for the audience. They’re really systems for exposition and re-examination, to play around with time like it was having a conversation with itself. It’s a neat effect when juggled smoothly, like when Past Oppenheimer is being interviewed by a steely and suspicious military intelligence office (Casey Affleck) while Future Oppenheimer laments to his project superior (Matt Damon) and then Even More Future Oppenheimer regrets his lack of candor to the review board. The shifty wheels-within-wheels nature of it all can be astounding when it’s all firing in alignment, but it can also feel like Nolan having a one-sided conversation with himself too often. It’s another reminder of the layers of narrative trickery and obfuscation that have become staples of a Christopher Nolan movie (I don’t think he could tell a knock-knock joke without making it at least nonlinear). The opposition to Oppenheimer is summarized by Strauss but I would argue the man didn’t need a public witch hunt to rectify what he’s done.

The last hour of the movie features a security clearance interrogation and a Senate confirmation hearing, neither of which have appealing stakes for an audience. After we watch the creation of a bomb, do we really care whether or not this one testy guy gets approved for a cabinet-level position or whether Oppenheimer might get his security clearance back? I understand that these stakes are meaningful for the characters, both essentially on trial for their lives and connections, but Nolan hasn’t made them as necessary for the audience. They’re really systems for exposition and re-examination, to play around with time like it was having a conversation with itself. It’s a neat effect when juggled smoothly, like when Past Oppenheimer is being interviewed by a steely and suspicious military intelligence office (Casey Affleck) while Future Oppenheimer laments to his project superior (Matt Damon) and then Even More Future Oppenheimer regrets his lack of candor to the review board. The shifty wheels-within-wheels nature of it all can be astounding when it’s all firing in alignment, but it can also feel like Nolan having a one-sided conversation with himself too often. It’s another reminder of the layers of narrative trickery and obfuscation that have become staples of a Christopher Nolan movie (I don’t think he could tell a knock-knock joke without making it at least nonlinear). The opposition to Oppenheimer is summarized by Strauss but I would argue the man didn’t need a public witch hunt to rectify what he’s done.

Lest I sound too harsh on Nolan’s latest, there are some virtuoso sequences that are spellbinding with technical artists working to their highest degree of artistry. The speech Oppenheimer gives to his Los Alamos colleagues is a horrifying lurch into a jingoistic pep rally, like he’s the big game coach trying to rally the team. The way the thundering stomps on the bleachers echo the rhythms of a locomotive in motion, driving forward at an alarming rate of acceleration, and then how Nolan drops the background sound so all we hear is Oppenheimer’s disoriented speech while the boisterous applause is muted, it’s all masterful to play with our sense of dread and remorse. This is who this man has become, and his good intentions of scientific discovery will be rendered into easily transmutable us-versus-them fear mongering politics. The ending imagery of Oppenheimer envisioning the world on fire is the exact right ending and hits with the full disquieting force of those three hours. The meeting with Harry Truman (Gary Oldman) is splendid for how undercutting it plays. Kitty’s interview at the hearing is the kind of counter-punching we’ve been waiting for and is an appreciated payoff for an otherwise underwritten character stuck in the Concerned Wife Back at Home role. The best parts are when Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves (Damon) are working in tandem to put together their team and location, as that’s when the movie feels like a well orchestrated buddy movie I didn’t know I wanted. The sterling cinematography, musical score, editing, all of the technical achievements, many of which won Oscars, are sumptuously glorious and immeasurably add to Nolan’s big screen vision.

I think I may understand why the subject of sex is something Nolan has conspicuously avoided before. Much has been made about the sex scenes and nudity in Oppenheimer, which seem to be the crux of Florence Pugh’s performance as Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s communist mistress through the years. The moment of Oppenheimer sitting during his hearing about his sexual tryst with an avowed communist leads to him imagining himself in the nude, exposed and vulnerable to these prying eyes and their judgment. Then Kitty imagines seeing Pugh atop her husband in his hearing seat, staring directly at her, and this sequence communicated both of their internal states well and felt justified. It’s the origin of the famous “I am become death” quote where the movie enters an unexpected level of cringe for a movie this serious. I was not prepared for this, so mild spoilers ahead if you care about such things, curious reader. We’re dropped into a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Jean where she takes a break to peruse his library shelves. She’s impressed that he has a Hindu text and pins it against her naked chest and slides atop Oppenheimer once again, requesting he read it to her rather than summarize it. “I am become death,” he utters, as he reads the Hindu Book of the Dead off Pugh’s breasts while they continue to have sex. Yikes. A big ball of yikes. If this is what’s in store, please go back to a sexless universe of men haunted by their lost women.

I think I may understand why the subject of sex is something Nolan has conspicuously avoided before. Much has been made about the sex scenes and nudity in Oppenheimer, which seem to be the crux of Florence Pugh’s performance as Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s communist mistress through the years. The moment of Oppenheimer sitting during his hearing about his sexual tryst with an avowed communist leads to him imagining himself in the nude, exposed and vulnerable to these prying eyes and their judgment. Then Kitty imagines seeing Pugh atop her husband in his hearing seat, staring directly at her, and this sequence communicated both of their internal states well and felt justified. It’s the origin of the famous “I am become death” quote where the movie enters an unexpected level of cringe for a movie this serious. I was not prepared for this, so mild spoilers ahead if you care about such things, curious reader. We’re dropped into a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Jean where she takes a break to peruse his library shelves. She’s impressed that he has a Hindu text and pins it against her naked chest and slides atop Oppenheimer once again, requesting he read it to her rather than summarize it. “I am become death,” he utters, as he reads the Hindu Book of the Dead off Pugh’s breasts while they continue to have sex. Yikes. A big ball of yikes. If this is what’s in store, please go back to a sexless universe of men haunted by their lost women.

It’s easy to be swept away by all the ambition of Nolan’s Oppenheimer, a Great Man of History biopic that I think could have been better by being more judiciously critical of its subject. It’s a thoroughly well-acted movie where part of the fun is seeing known and lesser known name actors populate what would have been, like, Crew Member #8 roles for the sake of being part of this movie (Rami Malek as glorified clipboard-holder). Oppenheimer takes some wild swings, many of them paying off tremendously and also a few that made me scratch my head or reel back. It’s a demonstrably good movie with top-level craft, but I can’t quite shake my misgivings that enough of the movie could have been lost to history as well.

Nate’s Grade: B

Napoleon (2023)

I may be completely in the wrong, but I feel the only way to view Ridley Scott’s latest historical epic, a 158-minute account of the life of Napoleon Bonaparte, is as a comedy with the full intention of not retelling history but of de-mythologizing the grandiosity of its star. Otherwise, these 158 minutes feel like an accelerated Wikipedia summary of the man’s many famous deeds as he rose from general to Emperor and swept his armies across the continent conquering much of Europe. Rather, I choose to think of the movie as a strange comedy that shows how this fearsome military genius might also have been just a strange little guy with a temper.

The Revolution in France is burning out of bodies and the people are growing restless at the lack of meaningful democratic progress. Enter Napoleon Bonaparte (Joaquin Phoenix) as a successful general who will eventually crown himself as Emperor of France. He will wage war across the continent, lead to the deaths of three million by his final defeat 1815, and reshape and revolutionize the military of its days. He will also die alone, exiled, and without the love of his life, his wife, Josephine (Vanessa Kirby).

This all has to be a comedy, right? Ridley Scott (Gladiator, The Last Duel) went to elaborate lengths to make fun of the little general, right? How else to read scenes where Napoleon and Josephine argue at the dinner table where he accuses her of being infertile, she accuses him of being fat, and he agrees that he heartily likes his food and says, “Fate has brought this lamb chop to me.” How else to read a scene where he throws a hilarious hissy fit before the English ambassador, who Napoleon feels has been rude and less than deferential, and he screams, “You think you’re so great because you have boats!” How else do you read a montage of Napoleon seizing power with the military pushing out the old figures of power and one of them, aghast, shouting, “This cannot be. I am enjoying a succulent breakfast!” How else to interpret the scene where Napoleon is going to achieve his coup from the French parliament and he’s run out of the chamber, falling and scampering out like a child caught playing tyrant. It’s moments like these, as well as the acting choices, that push me in the direction of interpreting this movie less as another handsomely mounted biopic of The Great Men of History and more tearing down the lockstep reverence for this figure glorified through centuries of back-patting. I’m reminded of Josh Trank’s relatively unloved Capone movie from 2020, and while imperfect, I appreciated that Trank spent the entire movie tearing down the legend and myth of this bad man and showed him for what he was late in life, a pathetic, decrepit loser riddled with syphilis losing his mind and crapping his pants. I think we need more biopics that have a less reverent approach to their subject because then it provides a public service of inviting viewers to be more critical of history rather than blindly accepting.

I think this is also showcased by the fact that Scott and screenwriter David Scarpa (All the Money in the World) are choosing to tackle the legends rather than the history. Take for instance the acclaimed Battle of Austerlitz, one of the film’s high-points. Napoleon surprises the combined Russian and Austrian troops by firing cannons at the frozen lake, causing it to shatter and entomb thousands of men to their watery graves. It’s a stunning visual sequence that blends the beauty and terror of the events and of course little of it happened in real life. In reality, the lake was really more a series of small ponds and reportedly very few enemy soldiers drowned. In reality, Napoleon never rode into battle as part of his cavalry. The generals stayed behind with orders. Or take for instance Napoleon’s ill-fated march into Russia, and when he arrives he’s so bored and thoroughly depressed as he sits on the empty throne in Moscow, acting like a little kid who is eager to go home already. That’s the difference between history as it happens and history as it is remembered, and that’s the myth-making that Scott is attempting to work through and re-contextualize for the many people who aren’t fanatical acolytes of the historical record. This is Scott saying he’s going to take all the myths and legends and make you critically reconsider.

Then there’s the relationship with Josephine which defines much of the movie, so much so that it provides explanations for why Napoleon left his first exile, because, apparently, he was upset his wife was seeing other people. The relationship plays out like one more of political maneuvering than romance, with some eyebrow-raising bedroom kinks to modernize the tale. Much of their conflict is on Napoleon’s inability to sire a male heir, which is put through the steps of the scientific method by his concerned and opportunistic mother as he attempts to father bastards with other women. This is the storyline that suffers the most from the accelerated pacing and editing, so consumed with moving from place to place and fitting in all the historical checkpoints. The larger nuance of this relationship, and Josephine as a character, is taken out by simplifying it as a tale of two people who realize that gender-specific baby-making is their top priority. In reality, Napoleon absolutely adored his wife and wrote lengthy love letters that you can read today, with lines such as, “I hope before long to crush you in my arms and cover you with a million kisses burning as though beneath the equator,” and, “Without his Josephine, without the assurance of her love, what is left him upon earth? What can he do?” It’s a shame so much of this is reduced to heir-production anxiety.

Phoenix (Beau is Afraid) plays the titular role like he’s sleepwalking, slumped and grumpy and rarely providing much energy except around plates of food. It’s a curious performance and one that helps me to further see the depiction as one through the lens of a critical offbeat comedy. He’s certainly not playing the man like he’s one of the great inspirational figures, and he’s certainly not playing the man like he’s tearing through a multitude of doubts and inner demons. He’s playing Napoleon like a grumpy weird little guy who would rather be dining than conquering. Kirby’s (Mission: Impossible Dead Reckoning) more an accessory in her character’s limited scope but she does have a few moments that reflect Josephine’s moxy.

I would be remiss to pass up this chance to sing the praises of my former high school AP history teacher, Mr. Jerry Anglim, who had been teaching history and government for over 26 years before I stepped foot in his classroom. The man brought history alive for me and really crystalized my love for the subject, seeing how it’s all just one big canvas of storytelling. And this man loved teaching the Napoleonic Wars in great detail, and I loved scribbling down those notes every day. I even thought about getting a Napoleon poster to hang in my room, which would have been quite the odd teenage decorating choice. We watched the 1970s Waterloo movie starring Rod Steiger as Napoleon in class on a tiny TV attached to the corner, and yet I was spellbound because of what this teacher had done for me with the subject. So, wherever you are Mr. Anglim, thank you, and I’m sure you have your complaints with this new movie and I would love to hear them.

As a long movie still barely chronicling the major events of its subject, Napoleon feels lacking unless viewed through the lens as a critical comedy tackling his legends and myths. Then the abrupt nature of the plotting becomes more an addition than a subtraction. However, Scott has gone on record that he has a four-hour director’s cut that Apple plans to make available on its streaming platform in the near future, so perhaps my entire interpretation could be blown up. To be fair, the real Napoleon was a military genius and did revolutionize and modernize the French military, and while he didn’t “conquer everything,” especially Great Britain and Russia, the man and his ambitions and good fortune dominated the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century. Human beings will always be drawn to the stories of conquerors, but it’s important to also see them as people, quite often terrible people, but human beings with failings and complexities that are often left behind from decades if not centuries of propaganda and historical whitewashing. As a biopic, Napoleon the movie feels too short and shrift. As a comedy, it’s a lamb chop served up by fate.

Nate’s Grade: C+

The Fabelmans (2022)

Steven Spielberg has been the most popular film director of the last fifty years but he’s never turned the focus squarely on himself, and that’s the draw of The Fabelmans, a coming-of-age drama that’s really a coming-of-Spielberg expose. The biographical movie follows the Fabelman family from the 1950s through the late 60s as Sammy (our Steven Spielberg avatar) becomes inspired to be a moviemaker while his parents’ marriage deteriorates. As a lifelong lover of movies and a childhood amateur filmmaker, there’s plenty here for me to connect with. The fascination with recreating images, of chasing after an eager dream, of working together with other creatives for something bigger, it’s all there and it works. I’m a sucker for movies about the assemblage of movie crews, those found families working in tandem. However, the family drama stuff I found less engaging. Apparently Sammy’s mother (Michelle Williams) is more impulsive, spontaneous, and attention-seeking, and may have some un-diagnosed mental illness at that, whereas his father (Paul Dano) is a dry and boring computer engineering genius. I found the family drama stuff to be a distraction from the storylines of Sammy as a budding filmmaker experimenting with his art and Sammy the unpopular new kid at high school harassed for being Jewish. There are some memorable scenes, like a girlfriend’s carnal obsession with Jesus, and a culmination with a bully that is surprising on multiple counts, but ultimately I found the movie to be strangely remote and lacking great personal insight. This is why Spielberg became the greatest filmmaker in the world? I guess. I’ll credit co-writer Tony Kushner (West Side Story, Lincoln) for not making this what too many modern author biopics have become, a barrage of inspirations and connections to their most famous works (“Hey Steven, I want you to meet our neighbor, Ernest Thalberg, or E.T. as we used to call him back at Raiders U.”). The Fabelmans is a perfectly nice movie, with solid acting, and the occasional moment that really grabs hold of you, like a electrifying meeting with a top Hollywood director in the film’s finale. For me, those moments were only too fleeting. It’s a family drama I wanted less family time with and more analysis on its creator.

Steven Spielberg has been the most popular film director of the last fifty years but he’s never turned the focus squarely on himself, and that’s the draw of The Fabelmans, a coming-of-age drama that’s really a coming-of-Spielberg expose. The biographical movie follows the Fabelman family from the 1950s through the late 60s as Sammy (our Steven Spielberg avatar) becomes inspired to be a moviemaker while his parents’ marriage deteriorates. As a lifelong lover of movies and a childhood amateur filmmaker, there’s plenty here for me to connect with. The fascination with recreating images, of chasing after an eager dream, of working together with other creatives for something bigger, it’s all there and it works. I’m a sucker for movies about the assemblage of movie crews, those found families working in tandem. However, the family drama stuff I found less engaging. Apparently Sammy’s mother (Michelle Williams) is more impulsive, spontaneous, and attention-seeking, and may have some un-diagnosed mental illness at that, whereas his father (Paul Dano) is a dry and boring computer engineering genius. I found the family drama stuff to be a distraction from the storylines of Sammy as a budding filmmaker experimenting with his art and Sammy the unpopular new kid at high school harassed for being Jewish. There are some memorable scenes, like a girlfriend’s carnal obsession with Jesus, and a culmination with a bully that is surprising on multiple counts, but ultimately I found the movie to be strangely remote and lacking great personal insight. This is why Spielberg became the greatest filmmaker in the world? I guess. I’ll credit co-writer Tony Kushner (West Side Story, Lincoln) for not making this what too many modern author biopics have become, a barrage of inspirations and connections to their most famous works (“Hey Steven, I want you to meet our neighbor, Ernest Thalberg, or E.T. as we used to call him back at Raiders U.”). The Fabelmans is a perfectly nice movie, with solid acting, and the occasional moment that really grabs hold of you, like a electrifying meeting with a top Hollywood director in the film’s finale. For me, those moments were only too fleeting. It’s a family drama I wanted less family time with and more analysis on its creator.

Nate’s Grade: B

Blonde (2022)

After receiving such blistering and excoriating responses, I went into writer/director Andrew Dominik’s Blonde with great trepidation. The near-three-hour biopic on the iconic Marilyn Monroe, played by Ana de Armas, is the first movie to earn an NC-17 rating since 2011’s Killer Joe, and as such, there’s a natural curiosity factor to any movie receiving such hostile reactions. Fans and critics have called the movie exploitative, navel-gazing, misogynistic, and redundant misery porn. One critic even said Blonde was “the worst movie Netflix has ever made.” I was a major fan of Dominik’s verbosely titled 2007 film, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and less so 2012’s Killing Them Softly, though I recognized sparing artistic merit. It’s been ten years since Dominik has directed a movie, so surely Blonde, based upon the novel by Joyce Carol Oates, had to have some merit beyond all its hype and criticism, right? Well, no. I processed my general disgust for Dominik’s three-hour slow-mo car crash. This movie is so stupendously misguided and cruel and filled with bizarre, outlandish, and maddening artistic decisions. For my movie review, I felt I needed to break my standard formula, so I decided to give voice to my analysis and criticisms by writing a pretend conversation between Dominik and a stand-in for the Netflix production. Enjoy, dear reader, and beware.

After receiving such blistering and excoriating responses, I went into writer/director Andrew Dominik’s Blonde with great trepidation. The near-three-hour biopic on the iconic Marilyn Monroe, played by Ana de Armas, is the first movie to earn an NC-17 rating since 2011’s Killer Joe, and as such, there’s a natural curiosity factor to any movie receiving such hostile reactions. Fans and critics have called the movie exploitative, navel-gazing, misogynistic, and redundant misery porn. One critic even said Blonde was “the worst movie Netflix has ever made.” I was a major fan of Dominik’s verbosely titled 2007 film, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and less so 2012’s Killing Them Softly, though I recognized sparing artistic merit. It’s been ten years since Dominik has directed a movie, so surely Blonde, based upon the novel by Joyce Carol Oates, had to have some merit beyond all its hype and criticism, right? Well, no. I processed my general disgust for Dominik’s three-hour slow-mo car crash. This movie is so stupendously misguided and cruel and filled with bizarre, outlandish, and maddening artistic decisions. For my movie review, I felt I needed to break my standard formula, so I decided to give voice to my analysis and criticisms by writing a pretend conversation between Dominik and a stand-in for the Netflix production. Enjoy, dear reader, and beware.

Andrew Dominick sits in front of the desk of a very concerned Netflix Producer, who fidgets uncomfortably in his seat and shuffles papers in his hands.

Netflix Producer: So, thanks, Andrew for making time for this meeting. We’ve seen your full movie and we have some… well, concerns.

Andrew Dominik: That’s life, man. You can’t tell stories without risk. Break a few eggs.

Netflix Producer: Yes, sure, but, well, I guess one of our biggest questions is why did you need almost three hours to devote entirely to the lengthy suffering of Marilyn Monroe? This is supposed to be a biopic, but all we get, scene after scene, to a fault, is a moment of Marilyn being abused, or crying, or being generally exploited. It’s… a lot to take in, Andrew.

Andrew Dominik: Hey man, that was her life. She was this glamorous star, but behind the glamor is a lot more dirt and grime. Everyone wanted to be her, and I wanted to show the world how wrong that would be. This is a woman who was desired by the world and she was still a victim in the Old Hollywood system, which was a rape factory. I was just being honest, man.

Andrew Dominik: Hey man, that was her life. She was this glamorous star, but behind the glamor is a lot more dirt and grime. Everyone wanted to be her, and I wanted to show the world how wrong that would be. This is a woman who was desired by the world and she was still a victim in the Old Hollywood system, which was a rape factory. I was just being honest, man.

Netflix Producer: I get that principle, but it really feels like the only version of Marilyn we get in this movie is the role of a long-suffering victim. It’s practically a passion play: The Passion of Marilyn Monroe. You’re cheapening her real-life suffering by making it so redundant to the point of self-parody, and also, if you were so concerned about creating an honest portrayal of what this woman went through, then why are you also making things up to add to her legitimate suffering?

Andrew Dominik: What d’ya mean? I adapted the book.

Netflix Producer: Yes, but you do know that Oates’ book is explicitly fictitious, right? It’s made up. Marilyn never had a throuple relationship with Charlie Chaplain Jr. and Edward G Robinson Jr. Marilyn had a positive relationship with her mother. Even worse, you’re adding fictitious suffering, like her relationship with her mother, or Marilyn being raped during an audition.

Andrew Dominik: Yeah, that might never have happened, but the rape represents the-

Netflix Producer: I’m gonna stop you there. You should refrain from sentences that include the phrase, “The rape represents [blank].” We don’t need literal sexual violence, of which we return to time and again, to stand in for a larger thematic message. Also, it’s quite disingenuous to add extra traumatic experiences when you’re purporting to tell this woman’s real trauma and conflict.

Andrew Dominik: Agree to disagree, then.

Netflix Producer: No, not really, but, okay, Andrew, can you tell me any personable impression you get of Marilyn from this movie? And-and you cannot say “victim.”

Netflix Producer: …Yes?

Andrew Dominik: Sexy?

Netflix Producer: Okay, sex symbol for nearly 60 years after her death, sure. What else?

Andrew Dominik: She was…. Um…. Uh… Can I look this up on my phone?

Netflix Producer: See, Andrew, this is our problem-

Andrew Dominik: Oh, she has daddy issues! There. That.

Netflix Producer: And for an hour you have her referring to all the men in her life as “daddy,” which is very uncomfortable especially when those men are literally abusing her.

Andrew Dominik: But, y’see, she calls ‘em all “daddy” because she has-

Netflix Producer: Oh, we get it. Thank you. You have 160 minutes and you keep hitting the same point over and over, bludgeoning the viewer into submission. It’s more than a bit gratuitous, especially when you factor that you’re adding even more trauma.

Andrew Dominik: What d’ya mean by “gratuitous?”

Netflix Producer: I have prepared several examples. For starters, it might be a bit much within the first twenty minutes of your movie to subject your audience to a mother trying to drown her child in the bathtub and Marilyn being sexually assaulted at one of her first auditions.

Andrew Dominik: Okay. Okay. I get that.

Netflix Producer: Then there’s the ghastly POV shot from inside Marilyn’s vagina, which by God happens twice, and both times it’s during forced abortions. Did we really need that queasy angle that is literally invading her body against her will to accomplish what exactly?

Andrew Dominik: The purpose of any true artist is to go deeper-

Netflix Producer: I’m gonna stop you there again. It’s just bad taste, Andrew. Also, speaking of bad taste, maybe we don’t need the entire sequence where JFK rapes her and then hires government goons to abduct her and force Marilyn into an abortion. And then, on top of all that, she hears the pleas of her first aborted fetus calling back to her. Yikes. Can you at any point step outside of your position, Andrew, and realize how shockingly gratuitous all of that can be?

Netflix Producer: I’m gonna stop you there again. It’s just bad taste, Andrew. Also, speaking of bad taste, maybe we don’t need the entire sequence where JFK rapes her and then hires government goons to abduct her and force Marilyn into an abortion. And then, on top of all that, she hears the pleas of her first aborted fetus calling back to her. Yikes. Can you at any point step outside of your position, Andrew, and realize how shockingly gratuitous all of that can be?

Andrew Dominik: It’s all designed to separate the person from the icon. Marilyn Monroe never really existed beyond the fantasies of the public, man. It’s about bringing back her humanity.

Netflix Producer: Separating the legend from the person would be a natural artistic angle, but that means spending time establishing the person, building her up through multiple dimensions, multiple opportunities to flesh her out. You only spend time seeing her as a victim, that is when we’re not meant to partake in the same sexualization of her that you seem to be criticizing. I mean the 1996 HBO TV movie managed by having two different actresses portray her, with Naomi Judd as Norma Jean and Mira Sorvino as Marilyn. That literalized the differences and even had Marilyn converse with her former persona as a plot device. You have none of that.

Andrew Dominik: I might not have that, but my movie has a cross dissolve that goes from Marilyn getting banged to the literal crest line of Niagara Falls.

Netflix Producer: I don’t think that really makes up for a lack of character substance.

Andrew Dominik: Agree to disagree, man.

Netflix Producer: You really can’t keep using that as a defense.

Andrew Dominik: Agree to disagree, man.

Netflix Producer: Your horror show of relentless trauma and bad taste might undercut your stated goal of humanizing this woman. She’s not a character but a symbol of abject suffering, a martyr, and you increase her suffering, and sometimes in grating, absurdly grotesque ways. Do you even care about this woman? You’ve devoted three hours to reanimating her as a powerless punching bag.

Andrew Dominik: Well, I did say Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is about “well-dressed whores” and that Blonde is “just another movie about Marilyn Monroe. And there will be others.” I also said that the most important part of her life was that she killed herself.

Netflix Producer: Exactly. That makes us question whether you have the passion and sensitivity for this project. Why does this movie even have to be NC-17? Will your three hour torture chamber be bereft of meaning if the audience doesn’t see two inner vaginal camera angles?

Netflix Producer: Exactly. That makes us question whether you have the passion and sensitivity for this project. Why does this movie even have to be NC-17? Will your three hour torture chamber be bereft of meaning if the audience doesn’t see two inner vaginal camera angles?

Andrew Dominik: How dare you even question my artistic integrity. If you remove those shots, you might as well be removing the soul of this movie. Why even tell this story?

Netflix Producer: Yes, why indeed?

Andrew Dominik: It’s meant to be disorienting.

Netflix Producer: Congrats.

The Netflix producer leans back in his chair and releases an extended, wearying sigh.

Andrew Dominik: So… after everything…. Are you going to make me cut anything?

Netflix Producer: Please. We’re so hungry for Oscar recognition, we don’t care. Go for it.

I want to cite de Armas’ (The Gray Man) performance as one of the few attributes to the movie. It’s hard to watch this woman suffer and cry in literally every scene, but I also just felt so sad for not just her character but for de Armas as an actress herself. She shouldn’t have to endure everything that she does to play this character. She is undercut by Dominik’s artistic antics and avarice at every turn, like the story jumping around incoherently so every scene fails to build upon one another. There is no genuine character exploration to be found here. It’s a cycle of suffering, and the movie wants to rub your nose in the exploitation of Monroe while simultaneously exploiting her. De Armas deserves better. Marilyn Monroe deserves better. Every viewer deserves better. Spare yourself three awful hours of pointless suffering in the name of misapplied art.

Nate’s Grade: F

Elvis (2022)

Elvis the movie is exactly what I would have hoped for from a Baz Luhrmann film, which is an experience that no one else can provide, a messy, chaotic, crazy, sometimes tin-eared yet audacious and immersive kaleidoscope of sight and sound that feels like a theme park ride. As with all Luhrmann films, the first 20 minutes is a rush of tones, characters, and near constant frenetic movement; it’s so much to process before the movie eventually settles down, at least marginally, or the viewer becomes better acclimated to the madcap storytelling style of this mad Aussie. I feel completely certain that people will call Elvis brilliant, and people will deem Elvis to be ridiculous and campy, and I would say it defiantly manages to be all of these identities at once. It is ridiculous, it is campy, it is emotional and sincere, it is, at points, even brilliant, and in a way, this shambolic style perfectly symbolizes Elvis himself, a performer that seems to be anything that the viewer projects onto him, a trailblazer who suffered for his art before becoming an irreplaceable industry and edifice of pop-culture obsession unto himself.

Elvis the movie is exactly what I would have hoped for from a Baz Luhrmann film, which is an experience that no one else can provide, a messy, chaotic, crazy, sometimes tin-eared yet audacious and immersive kaleidoscope of sight and sound that feels like a theme park ride. As with all Luhrmann films, the first 20 minutes is a rush of tones, characters, and near constant frenetic movement; it’s so much to process before the movie eventually settles down, at least marginally, or the viewer becomes better acclimated to the madcap storytelling style of this mad Aussie. I feel completely certain that people will call Elvis brilliant, and people will deem Elvis to be ridiculous and campy, and I would say it defiantly manages to be all of these identities at once. It is ridiculous, it is campy, it is emotional and sincere, it is, at points, even brilliant, and in a way, this shambolic style perfectly symbolizes Elvis himself, a performer that seems to be anything that the viewer projects onto him, a trailblazer who suffered for his art before becoming an irreplaceable industry and edifice of pop-culture obsession unto himself.

We chart the rise of Elvis Presley (Austin Butler) from a young crooner in the 1950s to the best-selling solo artist in recording history. Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks) discovers Presley, granted after he’s been a chart-topping local hit in the South, and sees a grand opportunity. With Elvis, there is no limit to where they both can go, and so Parker becomes Elvis’ manager for over twenty years for better and worse, engineering Elvis’ tour of duty in the military to take him away from negative headlines, only for him to meet and marry Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge), to locking him into a Vegas headlining gig to erase the mystery man’s heavy debts to the mob. Under Luhrmann’s guidance, you’ll experience it all and then some in the frenzied 160 minutes.

Elvis was many things for many people. He was a smooth crooner, he was an electric live performer, he was the benefactor of being a white vessel for music that was built upon the less heralded work of black performers, he was a victim, he was selfish, he was devoted to his fans and the stage, he was… America. In 2022, I would have asked if contemporary culture even cared about Elvis anymore, a man who died over 40 years ago, and whether we even have a lens to appreciate the man. Was he simply coasting off the hard work of other black performers? Did he groom his eventual bride considering her age upon their meeting? Was Elvis too old fashioned to even be anything other than a musical touchstone that other artists have surpassed? Is he just a joke? Luhrmann does a fine job of re-contextualizing Elvis, what made him unique for his era, and what made him still captivating to watch to this day. Even the archival footage the closes the movie is a reminder of the unmitigated power the man put into his singing.

Elvis was many things for many people. He was a smooth crooner, he was an electric live performer, he was the benefactor of being a white vessel for music that was built upon the less heralded work of black performers, he was a victim, he was selfish, he was devoted to his fans and the stage, he was… America. In 2022, I would have asked if contemporary culture even cared about Elvis anymore, a man who died over 40 years ago, and whether we even have a lens to appreciate the man. Was he simply coasting off the hard work of other black performers? Did he groom his eventual bride considering her age upon their meeting? Was Elvis too old fashioned to even be anything other than a musical touchstone that other artists have surpassed? Is he just a joke? Luhrmann does a fine job of re-contextualizing Elvis, what made him unique for his era, and what made him still captivating to watch to this day. Even the archival footage the closes the movie is a reminder of the unmitigated power the man put into his singing.

It wouldn’t be a Luhrmann movie without a narrator, and this time we get the story’s main antagonist as our prism to view Elvis, marking him chiefly as victim. Tom Parker is a cartoon of a character especially as portrayed by Hanks. I love me some Tom Hanks, the man is an American treasure, and I appreciate that the man is definitely going for broke, but I don’t know at all what he was going for with this performance (the makeup does him no favors also). Hanks is fascinating because he is playing a villainous character that is constantly trying to re-frame their villainy, telling his side of the story but being careful, though not that careful, to always have an answer for an accusation. It feels like Hanks has stepped off the wacky Moulin Rouge! stage and everyone else in the movie is playing things completely straight. The entire acting troupe is all playing under one direction, and then there’s Hanks in his fat suit, who is breaking through the fourth wall, compulsively narrating our story, and acting like a loquacious Loony Tunes figure any second away from his own song and dance. His repeated use of the term “snow job” and “snowman,” which he dubbed himself as a showman, is overused to the point of being a verbal crutch, reminiscent of how often Jay Gatsby had to say some variation of “ole sport” in the 2013 movie or else he might irrevocably burst into glitter (or so I assume). It’s such a bizarre performance of wild choices that I can subjectively say it might be Hanks’ worst and yet it also feels like Hanks is giving Luhrmann exactly what he wants. It’s such a bold move to essentially cede your famous biopic to the most ridiculous character to tell from their ridiculous perspective. Imagine I, Tonya being told from Paul Walter Hauser’s character or House of Gucci being told from Jared Leto’s character, and that’s what we have here. I almost kind of love it, and in doing so, we see from the manipulator how he worked his magic to keep financial control over Elvis. Even Elvis’ later years are provided with a perspective that re-frames the man as a victim of a moneymaking machine that wouldn’t stop until it had drained every last drop of blood from this hard-working man.

I think this is smart because, on the surface, Elvis might not be the most complicated person to devote two hours to unpacking his character dimensions. He liked to sing, as it touched something deep inside him, and he wanted to be true to himself, but this framework isn’t any different from any number of famous musician biopics we’ve become more than accustomed to. He dealt with drug addiction and erratic behavior but, again, even this is musical biopic basics. Even his doomed relationship with Priscilla is familiar stuff, as she could rarely compete with the demands and the allure of the stage. I think Luhrmann and his co-writers wisely saw that the best storytelling avenue with Elvis is through the lesser-known Colonel, a bizarre and calculating figure cackling in the shadows. There are significant questions over who this proud huckster really is and what he did to bully and cajole Elvis into his favor. There’s inherent conflict there as well as an angle that I would argue most are unfamiliar with. I didn’t know much about the history of Elvis the man but I knew even less about this would-be Colonel.

I think this is smart because, on the surface, Elvis might not be the most complicated person to devote two hours to unpacking his character dimensions. He liked to sing, as it touched something deep inside him, and he wanted to be true to himself, but this framework isn’t any different from any number of famous musician biopics we’ve become more than accustomed to. He dealt with drug addiction and erratic behavior but, again, even this is musical biopic basics. Even his doomed relationship with Priscilla is familiar stuff, as she could rarely compete with the demands and the allure of the stage. I think Luhrmann and his co-writers wisely saw that the best storytelling avenue with Elvis is through the lesser-known Colonel, a bizarre and calculating figure cackling in the shadows. There are significant questions over who this proud huckster really is and what he did to bully and cajole Elvis into his favor. There’s inherent conflict there as well as an angle that I would argue most are unfamiliar with. I didn’t know much about the history of Elvis the man but I knew even less about this would-be Colonel.

The most Luhrmann of sequences is Elvis’ breakthrough live performance where it feels like every woman in attendance is catching a fever of combustible hormonal fury. The way the man shook his hips, moved his body, his gyrations that so many adults felt were dangerously subversive, were part and parcel of the younger Elvis. He really was a born performer, and even says he can’t sing if he isn’t allowed to move how he feels he must with the music. During this crazy sequence, Luhrmann’s camera is trained on the emotional response of the audience experiencing a sensation that cannot be contained, bubbling to the surface into tears, shrieks, and convulsions, and it moves through the crowd like waves. It’s such an enthusiastic experience that plays right into the stylistic and tonal wheelhouse of Luhrmann. It’s also an unsubtle reminder, not that much is subtle in a Luhrmann movie, that part of the man’s appeal was his raw sexual magnetism.