Category Archives: 2024 Movies

Nosferatu (2024)

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Nate’s Grade: B

Smile 2 (2024)

In 2022, thanks to genius viral marketing and the acknowledgement how deeply unnerving happy people can be, Smile was a surprise horror smash hit. Writer/director Parker Finn expanded on a previous short film and made serious money, which meant a sequel was a given. Finn returns to lead Smile 2 to even creepier genre pastures, this time following the mental demise of a pop star, Skye Riley (Naomi Scott) trying to make sense of this malignant curse. As much as I enjoyed the first Smile for its careful development and visceral intensity, I think Smile 2 might be even better.

In 2022, thanks to genius viral marketing and the acknowledgement how deeply unnerving happy people can be, Smile was a surprise horror smash hit. Writer/director Parker Finn expanded on a previous short film and made serious money, which meant a sequel was a given. Finn returns to lead Smile 2 to even creepier genre pastures, this time following the mental demise of a pop star, Skye Riley (Naomi Scott) trying to make sense of this malignant curse. As much as I enjoyed the first Smile for its careful development and visceral intensity, I think Smile 2 might be even better.

From the opening sequence, it’s clear that we’re in the hands of a filmmaker that knows exactly what they’re doing. This is not merely another paycheck for Finn. He’s thought about how a sequel can build from its predecessor, stand on its own, incrementally build out the mythology, but mostly how to be an expertly made horror thriller designed to get under your skin. There were multiple sequences where I kept muttering variations of , “No,” or, “I don’t like that at all,” enough so that my wife in the other room would inquire what was directing these responses. Finn is tremendous at setting up the particulars of a scare sequence and allowing the audience to simmer in that anxious period of dread as we wait for something sinister to happen. He reminds me of James Wan and his ability to set up a nasty little scenario and then traps you inside awaiting the worst. There are sequences that compelled me to look away, not simply because they were overpowering, though the gore and makeup effects can best be described as impressively gross, but because the movie was finding different ways to make me uncomfortable, but in that good horror movie way. Finn’s camera makes what we should fear very clear, and his editing is precise. This is a movie that wants you to see the darkness and persistently worry about what’s coming just out of the frame.

One of my minor complaints with the first Smile was that there wasn’t much below its grinning surface. Sure, the entire premise of a curse that spreads through witnessing horrific acts of self-harm lends itself toward the discussion of how trauma begets trauma, but beyond that the first film was more reliant upon supreme craft and well-engineered scares. There’s nothing wrong with a movie that exists primarily as a thrill ride as long as those thrills deliver upon their promise. However, with Smile 2, Finn uses the character of Skye Riley as a beginning point to discuss the toxic relationships that come with fandom. It should be very obvious for every viewer that Skye is going through some serious issues. She’s overcoming addiction, physically rehabilitating her body as well as socially rehabilitating her image, and trying to learn all her new choreography for an intense world tour. This is a woman who could use a significant break. And yet, as the movie progresses, you start to sense that there is this large machinery around her that needs her to perform because that is how she makes them all money. Even her own mother-as-manager (Rosemarie DeWitt) can seem questionable as far as her motivations; is she pushing her child because she knows it’s what best for her to focus on for recovery, or is she pushing her because the tour pays for her lifestyle? As the movie progresses, the characters fret that Skye’s increasingly bizarre behavior is going to ruin the tour first and foremost, and concern for her actual well-being is secondary at best. All these people have their paychecks attached to this woman fulfilling her contractual obligations. You can also extrapolate the intense pressure the industry places on people with mental illness and self-destructive personalities to conform to standards that are unfair and often un-meetable. You might question why more pop stars don’t have head-shaving outbursts.

One of my minor complaints with the first Smile was that there wasn’t much below its grinning surface. Sure, the entire premise of a curse that spreads through witnessing horrific acts of self-harm lends itself toward the discussion of how trauma begets trauma, but beyond that the first film was more reliant upon supreme craft and well-engineered scares. There’s nothing wrong with a movie that exists primarily as a thrill ride as long as those thrills deliver upon their promise. However, with Smile 2, Finn uses the character of Skye Riley as a beginning point to discuss the toxic relationships that come with fandom. It should be very obvious for every viewer that Skye is going through some serious issues. She’s overcoming addiction, physically rehabilitating her body as well as socially rehabilitating her image, and trying to learn all her new choreography for an intense world tour. This is a woman who could use a significant break. And yet, as the movie progresses, you start to sense that there is this large machinery around her that needs her to perform because that is how she makes them all money. Even her own mother-as-manager (Rosemarie DeWitt) can seem questionable as far as her motivations; is she pushing her child because she knows it’s what best for her to focus on for recovery, or is she pushing her because the tour pays for her lifestyle? As the movie progresses, the characters fret that Skye’s increasingly bizarre behavior is going to ruin the tour first and foremost, and concern for her actual well-being is secondary at best. All these people have their paychecks attached to this woman fulfilling her contractual obligations. You can also extrapolate the intense pressure the industry places on people with mental illness and self-destructive personalities to conform to standards that are unfair and often un-meetable. You might question why more pop stars don’t have head-shaving outbursts.

Because we know that the evil entity has the power to alter our sense of sight and sound, it means the viewer must be actively skeptical about what is happening. Is this really happening? Is this sort of happening but elements are different? Or is this completely a hallucination? It makes the plot the equivalent of shifting sand, never allowing us to be comfortable or complacent. This can lead to positive and negative feelings. It keeps things lively but it can feel like the plot never really moves forward, at least in a cause-effect accumulation. It can often feel like the movie is moving in starts and stops, and if you’re not onboard for the craft, the acting, and the scares, then the results can likely feel frustrating, especially when large swaths of time are canceled out. For me, I enjoyed the extra sensory game of keeping me alert because it led to a barrage of surprises and rug pulls, some of them admittedly annoying, especially losing what amounts to maybe an entire act of the movie, but also they were a definite way to keep upending the narrative certainty. This sneaky approach also very viscerally places us in the paranoid mindset of our protagonist, as we too are unable to trust our senses and tense up with certain unsettling auditory cues. Mainly, I was having too much fun with the devious twists and turns, and some wickedly disturbing imagery from the director, that I felt like it was an ongoing thrill ride through a funhouse of insanity that kept me guessing.

In a just world, Scott (Aladdin, Charlie’s Angels) would be at the front of the pack in the discussion for the Best Actress Oscar. This woman is put through the proverbial wringer and she showcases every frayed nerve, every degenerating thought with such verve and command. It’s essentially a performance of a woman completely breaking down mentally, but Scott doesn’t just go for broke, putting every ounce of effort into inhabiting the breakdown, she creates a character that reveals herself through the breakdown. It’s not just screaming hysterics and histrionics; there are different levels to her dismantling psyche, and Scott portrays them beautifully. I felt such great levels of dread for her because of how successfully Scott was able to anchor my emotional investment. She’s also portraying different versions of Skye, and some key flashbacks reveal just how toxic her former addict self was that she’s trying to put to rest. It’s a performance about metaphorical demons and literal demons haunting a woman, as well as guilt that is eating her alive. Scott allows us the pleasure of watching a first-class performance through her shattering.

In a just world, Scott (Aladdin, Charlie’s Angels) would be at the front of the pack in the discussion for the Best Actress Oscar. This woman is put through the proverbial wringer and she showcases every frayed nerve, every degenerating thought with such verve and command. It’s essentially a performance of a woman completely breaking down mentally, but Scott doesn’t just go for broke, putting every ounce of effort into inhabiting the breakdown, she creates a character that reveals herself through the breakdown. It’s not just screaming hysterics and histrionics; there are different levels to her dismantling psyche, and Scott portrays them beautifully. I felt such great levels of dread for her because of how successfully Scott was able to anchor my emotional investment. She’s also portraying different versions of Skye, and some key flashbacks reveal just how toxic her former addict self was that she’s trying to put to rest. It’s a performance about metaphorical demons and literal demons haunting a woman, as well as guilt that is eating her alive. Scott allows us the pleasure of watching a first-class performance through her shattering.

There’s a curious motif to the movie that many will probably ignore but my wife and I fixated on, and so I feel the need to briefly discuss this so that, you too dear reader, can have this fixation as well. There are at least four scenes where Skye drinks a large bottle of water in a manner that can be best described as monstrously destructive. She drinks that bottle like a lost man in the desert finding his first drink of water. She attacks it. My best analysis is that this is a character detail about Skye’s addictive personality and sense of dependency, projecting the same all-consuming need onto water that she had previously for narcotics. One of the best laughs is when a doctor takes stock of Skye and says how dehydrated she is. Regardless, take in how desperately Skye Riley drinks and think about perhaps applying that technique next time you need a refreshing drink.

By its nightmarish conclusion, Smile 2 finds a fitting and satisfying end stop that promises a possible even bigger and more disturbing escalation for a Smile 3. Finn has established himself with two movies as a major horror filmmaker who can work within the mid-major studio system and still keep a perspective and integrity. I’m pleased that Smile 2 isn’t just more of the same old Smile, and in fact very few instances involve strangers with that signature facial expression. By the time you’re seeing the smile, it’s usually too late. I enjoyed the choice to find menace and darkness in a world of pop music brightness (the fake pop songs actually sound indistinguishable from what currently airs on the radio, bravo). I enjoyed the continuing tradition of casting famous Hollywood scions, like Jack Nicholson’s son playing Skye’s dead boyfriend (that family grin is uncanny, also bravo). What I really enjoyed was Scott’s uncompromising performance. Smile 2 has convinced me that Finn is the real deal, Scott might be one of our best modern scream queens and young actors, and to confirm introverted habits to avoid anyone who looks directly at me and smiles.

By its nightmarish conclusion, Smile 2 finds a fitting and satisfying end stop that promises a possible even bigger and more disturbing escalation for a Smile 3. Finn has established himself with two movies as a major horror filmmaker who can work within the mid-major studio system and still keep a perspective and integrity. I’m pleased that Smile 2 isn’t just more of the same old Smile, and in fact very few instances involve strangers with that signature facial expression. By the time you’re seeing the smile, it’s usually too late. I enjoyed the choice to find menace and darkness in a world of pop music brightness (the fake pop songs actually sound indistinguishable from what currently airs on the radio, bravo). I enjoyed the continuing tradition of casting famous Hollywood scions, like Jack Nicholson’s son playing Skye’s dead boyfriend (that family grin is uncanny, also bravo). What I really enjoyed was Scott’s uncompromising performance. Smile 2 has convinced me that Finn is the real deal, Scott might be one of our best modern scream queens and young actors, and to confirm introverted habits to avoid anyone who looks directly at me and smiles.

Nate’s Grade: A-

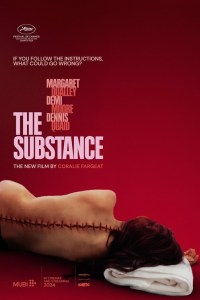

The Substance (2024)

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

Elisabeth (Demi Moore) is a television fitness instructor who has been massively popular for decades. Upon her 50th birthday, she’s promptly dismissed from her job by her studio, concerned over her diminished appeal as a sex symbol. She gets word of a mysterious elixir that can help her reverse the ravages of aging. It arrives via a clandestine P.O. box in a container with syringes and very specific instructions. She needs to spend seven days as her younger self, and seven days as her present self. She needs to “feed” her non-primary self. She also needs to understand that she is still the same person and not to get confused. Elisabeth injects herself with the serum and, through great physical duress, “Sue” emerges from her back like a butterfly sprouting from a fleshy cocoon. As Sue (Margaret Qualley), she’s now able to bask in the fame and attention that had been drifting away. Sue becomes the next hot fitness instructor and everything the studio wants. Except she’s enjoying being Sue so much that going back to her Elisabeth self feels like a punishment. Sue/Elisabeth starts to cheat the very specific rules of substance-dom, and some very horrifying results will transpire as she becomes increasingly desperate to hold onto what she has gained.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

I found the exploration of identity between Sue and Elisabeth to be really interesting, as we’re told repeatedly in the instructions that the two are the same person, and yet the two versions view the other with increasing resentment and hostility. For all intents and purposes, it’s the same woman trying on different outfits of herself, but that doesn’t stop the dissociation. In short order, the two versions view one another as rivals fighting over a shared resource/home. Sue becomes the preferred version and thus the “good times” where she can feel at her best. The older Elisabeth persona then becomes the unwanted half, and the weeks spent outside the coveted persona are akin to a depression. She keeps to herself, gorges on junk food, and anxiously counts the prolonged hours until she can finally transform into Sue. Again, this is the same character, but when she’s wearing the younger woman’s body, it can’t help but trick her into feeling like a different person. This division builds a fascinating antagonism ultimately against herself. She’s literally fighting with herself over her own body, and that sounds like pertinent social commentary to me.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

This is a first-rate body horror parable with wonderfully surreal touches throughout. The creation of Sue, being born from ripping from Elisabeth’s back, is an evocative and shocking image, as is the garish stapling of Elisabeth’s back/entry wound (why it makes for the poster’s key image). It’s reminiscent of a snake slithering out of its old skin, but to also have to take care of that old skin, knowing you have to metaphorically slide it back on, is another matter entirely. The literal dead weight is a reminder of the toll of this process but it’s also like they’ve been given a dependant. The spinal fluid injections are another squirm factor. I loved the way the Kubrickian production design heightens the unreality of the world. I won’t spoil where exactly the movie goes, but know that very bad things will happen beyond your wildest predictions. The finale is a tremendously bonkers climax that fulfills the gonzo, blood-soaked madness of the movie. If you’re a fan of inspired and disturbing body horror, The Substance cannot be missed.

Demi Moore is a fascinating selection for our lead. While it might have been inspired to have Qualley (Maid, Kinds of Kindness) play the younger version of her mother, Andie McDowell (Groundhog Day), it’s meaningful to have Moore as our aging figure of beauty standards. Here is an actress who has often been defined by her body, from the record payday she got for agreeing to bare it all in 1996’s Striptease, to the iconic Vanity Fair magazine cover of her nude and pregnant, to the roles where men are fighting over her body (Indecent Proposal), she’s using her body to tempt (Disclosure), or she’s using her body to push boundaries (G.I. Jane). It’s also meaningful that Moore has been out of the limelight for some time, mimicking the predicament for Elisabeth. Because of her personal history, the character has more meaning projected onto her, and Moore’s performance is that much richer. It reminded me of Nicolas Cage’s performance in Pig, a statement about an artist’s career that has much more resonance because of the years they can parlay into the lived-in role. Moore is fantastic here as our human face to the pressures and psychological torment of aging. She has less and less to hold onto, and in the later stretches of the movie, while Moore is buried under mountains of mutation makeup, she still manages to show the scared person underneath.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Much needs to be said about the hyperbolic sexualization of its characters, particularly Sue as the new young fitness star. Obviously our director is intending to satirize the default male gaze of the industry, as her camera lingers over tawny body parts and close-ups of curves, crevices, and crotches. However, the sexual satire is so ridiculously exploitative that it passes over from being too much and back to the sheer overkill being the point. This is not a movie of subtlety and instead one of intensity to the point that most would turn back and say, “That’s enough now.” For a movie about the perils and pleasures of the flesh, it makes sense for the photography to be as amplified in its rampant sensuality. There are segments where every camera angle feels like a thirsty glamour shot to arouse or arrest, but again this is done for a reason, to showcase Elisabeth/Sue as the world values them. The over-the-top male gaze the movie applies can be overpowering and exhausting, but I think that’s exactly Fargeat’s point: it’s reductive, insulting, and just exhausting to exclusively view women on these narrow terms. This isn’t quite our world, as the number one show on TV is an aerobics instructor, but it’s still close enough. I can understand the tone being too much for many viewers, but if you can push through, you might see things the way Fargeat does, and every lingering and exaggerated beauty shot might make you chuckle. It’s body horror on all fronts, showing the grotesquery not just in how bodies degrade but how we degrade others’ bodies.

On a personal note, while I’ll be back-dating this review, I wrote portions of it while sitting at my father’s bedside during his last days of life. He’s the person that instilled in me the love of movies, and I learned from him the shared language of cinematic storytelling, and one of my regrets is that I didn’t go see more movies with my father while we could. I really wish he could have seen The Substance because he was always hungry for new experiences, to be wowed by something he felt like he hadn’t quite seen before, to be transported to another world. He was also a fan of dark humor, ridiculous plot twists, and over-the-top violence, and I can hear his guffawing in my head now, thinking about him watching The Substance in sustained rapturous entertainment. It’s a movie that evokes strong feelings, chief among them a compulsive need to continue watching. It’s more than a body horror movie but it’s also an excellent body horror movie. Fargeat has established herself, in two movies, as an exciting filmmaker choosing to work within genre storytelling, reusing the tools of others to claim as her own with a proto-feminist spin and an absurdist grin. The Substance is the kind of filmgoing experience so many of us crave: vivid and unforgettable. And, for my money, the grossest image in the whole movie is Dennis Quaid slurping down shrimp.

Nate’s Grade: A

Anora (2024)

The critically-anointed Anora is the indie of the year, winning top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the first for an English-speaking movie in over a dozen years, and poised to be a major awards player down the stretch, some might even say front-runner for top prizes. It starts like a deconstruction of Pretty Woman, with Mikey Madison (Scream 5) playing Anora, a stripper who recognizes the advantageous possibilities flirting with a young rich Russian scion, Vanya. He wants her to be his girlfriend, and over a sex-fueled week, he’s so smitten that he wants to make Anora his wife. This whirlwind relationship hits the wall, however, once Vanya’s family inserts themself into his life, determined to annul the hasty marriage at all costs.

The critically-anointed Anora is the indie of the year, winning top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the first for an English-speaking movie in over a dozen years, and poised to be a major awards player down the stretch, some might even say front-runner for top prizes. It starts like a deconstruction of Pretty Woman, with Mikey Madison (Scream 5) playing Anora, a stripper who recognizes the advantageous possibilities flirting with a young rich Russian scion, Vanya. He wants her to be his girlfriend, and over a sex-fueled week, he’s so smitten that he wants to make Anora his wife. This whirlwind relationship hits the wall, however, once Vanya’s family inserts themself into his life, determined to annul the hasty marriage at all costs.

The movie becomes infinitely better at the hour mark when the exasperated extended Russian family comes into the picture. You worry they might be menacing, as they don’t want this stranger with access to the family wealth, but they’re far more bumbling, and Anora transforms into an unexpected comedy. It certainly wasn’t an authentic romance. Clearly Vanya was a meal ticket more than a three-dimensional romantic interest. The kid is an immature, annoying dolt, so we know Anora isn’t legitimately falling in love with him. The scenes of them building a “relationship” could have been cut in half because we already understood the nature of the two of them using one another. The last hour makes for a greatly entertaining turn of events as the unlikely and bickering posse searches New York City for a runaway Vanya. The movie feels propulsive and chaotic and blissfully alive. Ultimately, I don’t know what it all adds up to. Anora isn’t really a sharply drawn character, but none of the characters are particularly well developed. The pseudo-romantic fantasy of its premise, becoming a “princess” of luxury, isn’t really deconstructed with precision. It’s an unexpectedly funny ensemble comedy at its best, but I’m left indifferent to what other value I can take away. It’s well-acted and surprising, but it’s a vacuous side excursion made into a full movie that somehow has bewitched movie critics into seeing more. Perhaps they too have become overly smitten with Anora’s surface-level charms.

Nate’s Grade: B-

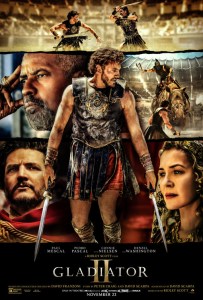

Gladiator II (2024)

It’s been twenty-four years since Russel Crowe, in his Oscar-winning role, bellowed, “Are you not entertained?” We were, we really were, and Gladiator was a huge hit in 2000 but has also held up as a twenty-first century classic that revived the sword-and-sandals epic. The late sequel hews quite closely to the path of the original Gladiator, a rare example of a movie that was quite literally writing the script as they went and succeeded wildly. The second go-round has a strong same-y feel, which is natural with sequels, but it also has trouble simply standing in the shadow of its superior predecessor.

It’s been twenty-four years since Russel Crowe, in his Oscar-winning role, bellowed, “Are you not entertained?” We were, we really were, and Gladiator was a huge hit in 2000 but has also held up as a twenty-first century classic that revived the sword-and-sandals epic. The late sequel hews quite closely to the path of the original Gladiator, a rare example of a movie that was quite literally writing the script as they went and succeeded wildly. The second go-round has a strong same-y feel, which is natural with sequels, but it also has trouble simply standing in the shadow of its superior predecessor.

This time we follow Paul Mescal (Aftersun) as a Roman expat who’s been living abroad as a simple man of the people, except when violence is called upon. His land is conquered by Rome, his beloved is killed, and he’s sold into slavery only to be selected to be trained as a gladiator and only to become a fan favorite who could possibly unseat the Emperor(s). Sounds familiar, right, plus with the revenge motivation? Mescal is playing Lucius, the adult nephew to the late emperor played by Joaquin Phoenix. He’s all grown up and with abs. This Maximum stand-in is actually the blandest character in the film, a scolding figure who says little and doesn’t want to be in any position of leadership. It makes for a lackluster hero especially compared to the presence and magnetism of Crowe in his leading man prime. Fortunately there’s entertaining side characters, notably Denzel Washington (The Equalizer) as a bisexual wheeler-dealer who manipulates his way to the top of the Roman Senate, even garnering the attention of the hedonist twin emperors. The script utilizes a lot of conveniences, from revelations of bloodlines to an adjacent crypt that just so happens to have old Maximus’ armor and sword. Washington’s schemes, more loose-goosey and the benefit of convenient luck than machiavellian plotting, provide the missing entertainment value from Mescal’s underdog-seeking-vengeance arc. Director Ridley Scott returns and stages some fun Colosseum action set pieces, including an aquatic based naval battle with literal sharks. The opening siege against a coastal city by the powerful Roman army is wonderfully visualized. I was never bored but I can’t say that the movie is operating at close to the same level. The second half kind of creaks to a close, with a final one-on-one that feels too lopsided and unfulfilling. The emotional resonance of the prior movie is sufficiently lacking. While Gladiator II can still get your blood moving, it’s also an exercise in rote blood-letting as diminished franchise returns.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Wicked: Part One (2024)

It’s shocking that it took this long for Wicked to make its way from the Broadway stage to the big screen. The musical, based upon Gregory Maguire’s novel, began in 2003 and while it may have lost out on the biggest Tony Awards that year to Avenue Q (it seems astonishing now but… you just had to be there in 2004, theater kids) the show has been a smash for over two decades, accruing over a billion dollars as the second highest-grossing stage show of all time. As show after show got its turn as a movie, I kept wondering what was taking so long with an obviously mass appealing show like Wicked. It’s the classic Hollywood desire of “same but different,” a reclamation project for none other than the Wicked Witch of the West, retelling her tale from her perspective. Well, Wicked’s time has eventually dawned, and the studio is going to feast upon its protracted wait. Taking a page from the YA adaptation trend that dominated the 2010s, they’ve split the show into two movies, separated by a full year, hoping to better capitalize on the phenomenon. I was wary about Part One being 150 minutes, the same length as the ENTIRE Wicked stage show, but having seen the finished product, and by “finished” I mean one half, I can safely say that Wicked is genuinely fabulous and deftly defies the gravity of expectations.

In the fantasy world of Oz, the green-skinned outcast Elphaba (Cynthia Erivo) is looked at with scorn, derision, and fear. She’s always been different and never fully accepted by her father who blames her for her mother’s death and her younger sister Nessarose (Marissa Bode) being stricken to a wheelchair. Nessa is going to study at Shiz University with all the other up-and-coming coeds of the land of Oz, including Glinda (Arianna Grande), a popular and frivolous preppie gal peppered in pink pastels. Glinda desperately wants to be taken seriously and become a witch, studying magic under the tutelage of the esteemed Madame Morrible (Michelle Yeoh). Instead, Morrible’s fascination falls upon Elphaba after she reveals her tremendous magical ability in a moment of extreme emotion. Now Elphaba is enrolled at the magic school and learning about the way of the world, and she’s stuck with Glinda as her roommate. The two women couldn’t be any more different but over the course of the movie, we’ll uncover how one became Glinda the Good and the other the Wicked Witch of the West.

At two-and-a-half hours long, again the length of both acts of the stage show, Wicked Part One only covers the events of the show’s first act, and yet it feels complete and satisfying and, even most surprising, extremely well paced. It’s hard for me to fathom what could have been lost to get the running time down as each scene adds something valuable to our better understanding of these characters and their progression and the discovery of the larger world. It’s a movie that feels constantly in motion, propelling forward with such winning ebullient energy that it becomes infectious. It’s also not afraid to slow things down, to allow moments to breathe, and to provide further characterization and shading that wasn’t included in the stage show. The adaptation brings the fireworks for the finale and raises the visual stakes and danger in a manner that feels exciting and compellingly cinematic. Considering the resplendent results, I feel I could argue that the movie is actually -here comes the heretical hyperbole, theater kids- an improvement over the stage musical. It makes me even more excited for a bolder, longer, potentially even more emotionally satisfying second part in November 2025.

One of my primary praises for 2021’s In the Heights was that director John M. Chu, who cut his teeth helming the Step Up movies, knows exactly how to adapt musicals to maximize the potential of the big screen. If you’re a fan of musicals, old and new, you’ll find yourself swept away with the scope and intricacy of these large fantasy worlds, the flourishes of costume and production design, as well as the creative choreography making fine use of spaces and the power of film editing. There’s a rousing dance sequence set in a library with shelves that rotate around the room, making the slippery choreography that much more immersive, impressive, and acrobatic. Even big crowd numbers are given the knowing framing and sense of scale to hit their full potential, from the opening rendition of Munchkinland celebrating the death of the Wicked Witch of the West complete with giant burning effigy that would make a Wickerman envious, to the introduction to the City of Oz where it appears every citizen has a jovial role to play in welcoming strangers to their enchanted capital city. Chu’s nimble camerawork allows us to really enjoy the staging and skills of the talent onscreen, bringing a beating sense of vitality we crave from musical theater writ large. Wicked is simply one of the best stage-to-screen adaptations in musical theater history and a joyous experience that allows the viewer sumptuous visuals.

At its core, the story of Wicked is about some pretty resonant themes like self-acceptance, bullying, the fear of what is different or misunderstood, and all of this is built upon an irresistible friendship between Glinda and Elphaba. The rivals-to-allies formula isn’t new but it is tremendously effective and satisfying, especially when both characters are as well drawn and deserving of our empathy as these two ladies. They’re each on a different meaningful character arc for us to chart their personal growth and disillusion with what they’ve been taught is The Way Things Are. One is starting from a disadvantaged position and gaining traction through an outward demonstration of power, and the other is beginning in a position of privilege and becoming humble and more considerate as she acknowledges the challenges of others in a manner that doesn’t have to reconfirm her enviable “goodness.” It just works, and both women are fantastic in their roles. I was on the verge of tears at several points and my heart felt as full as a balloon throughout because of the emotional engagement and heartwarming camaraderie between our two leading ladies. With all its razzle dazzle, Wicked is a story of feminine friendship first and foremost and emotionally rewarding to experience, with the soaring music as a bonus.

Let’s finally talk about the music, a key factor in the enjoyment of any musical, naturally. The music was written by Stephen Schwartz, the Oscar-winning composer for “Colors of the Wind” from Pocahontas as well as “Believe” from The Prince of Egypt. I found his Wicked numbers to range from good to astoundingly good, with catchy ear-worms like “Popular” to the anthemic power and sweep of “Defying Gravity.” The cheeky and toe-tapping “Dancing Through Life” is a showcase for Jonathan Bailey (Bridgerton) and benefits from the aforementioned creative library choreography. “I’m Not That Girl” is a heartbreaking ode to the girls who don’t think of themselves as enough, which is begging for a reappearance in Part Two. The only clunker is “A Sentimental Man” but that’s more the result of the deficiencies of Jeff Goldblum as a singer than the song. I await the reuse of themes and motifs that will make the music even more thematically rich in the eventual Part Two.

Count me as part of the skeptical throng when it was announced that Grande, who hasn’t acted in over ten years, was cast as Glinda. I’m here to say that she is uniformly great. The Glinda role is the more outwardly showy role and thus immediately more memorable. It’s the far more comedic role, in fact the main source of comedy in the show, and Grande has serious comedic chops. Naturally she excels with the singing and its purposeful miasmic bombast, but it’s the subtle comedic styling and the exaggerated physicality that impressed me the most, like a moment of her twirling on the floor as an added dramatic flourish. There’s one scene where she’s just marching up and down a hallway in full exuberance, kicking, dancing, and exploding with joy. I anticipated that Erivo (Bad Times at the El Royale) would be exceptional, and of course the Broadway vet is, as she brings such simmering life to Elphaba. There’s a strength in equal measure to her vulnerability, making the character fully felt. Erivo also delivers during the big moments, like the climax of the movie that can give you goosebumps in hiw it weaves together empowerment and defiance and self-acceptance. Together, the two women are an unbreakable pair of performers and heroes that we’ll want to see triumph over adversity.

After decades of belabored waiting, Wicked finally makes its journey from stage to screen and I must say it was worth every minute. The film, even at only one half, feels complete and richly realized, building upon the strong foundation of the stage show and its numerous winning elements and masterfully translating them to cinema, taking full advantage of the visual possibilities while also expanding upon the story and themes for further enrichment. While born in the early 2000s War on Terror Bush era of politics, Wicked’s themes of anti-immigrant fear-mongering as scapegoats still bears striking resonance today, as do the emerging warnings of fascism in Oz. If you’re a fan of The Wizard of Oz, musical theater, or even just grandiose spectacle that doesn’t dilute grandiose feelings, then step into Wicked and you too will feel like you’re floating on air.

Nate’s Grade: A

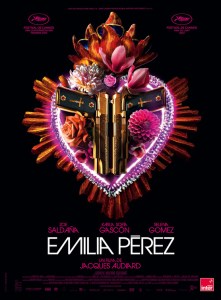

Emilia Perez (2024)

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of the cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air 210quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think work as musicals.

In contrast, Netflix’s Emilia Perez is like an entire season of a telenovela streamlined into a two-hour-plus movie that manages to also, for better or worse, be a musical. It is filled with many outlandish and provocative elements you would never expect to be associated with singing and dancing, like a sex change surgery center. This movie mixes so many genres and tones that at one point it feels like you’re watching a crime thriller about Mexican cartels and their manipulation of those in power, and then the next moment it feels like you’re watching an absurd rendition of Mrs. Doubtfire, where a spouse has adopted a new identity and uses this to spend time with their kids they otherwise would not be able to do so. It’s a wild film-going experience; I can’t recall too many musicals that use street stabbings in syncopation with percussion. Because of its go-for-broke ambitions and veering tones, Emilia Perez is destined to be a cult movie, some that fall in love with its bizarre mishmash of elements, but most will probably be stupefied by the entire experience and questioning why, exactly, this was made into a musical.

In Mexico City, Rita Castro (Zoe Saldana) is a savvy defense lawyer tired of living in the shadows of her buffoonish bosses that rely upon her writing prowess to win cases. Someone sees great potential with her, and it happens to be Manitas del Monte (Karla Sofia Gascon), the head of a dangerous cartel. He wants Rita to find the international means to finish the process of Manitas surgically becoming a woman. Under the gun, metaphorically and literally, Rita finds the doctors who will transform the dangerous him into a new her. Manitas then fakes their death, leaving his old life behind to start anew, including their children and wife, Jessi (Selena Gomez). Manitas becomes the titular Emila Perez, but rather retire in luxury, she wants to do good, and Emilia begins a non-profit organization that exhumes bodies, victims from the cartels, to provide closure for their widows and grieving families. Emilia then invites Jessi and their kids to come live in her estate, explaining she is a formerly unknown “aunt” to Manitas. Now Rita is trying to run Emilia’s organization, keeps Emilia from going too far in revealing her identity, and looking out for her own sake considering she’s one of the few that knows about a life before Emila Perez.

I know there will be hand-wringing and cultural tut-tut-ing about the movie’s implicit and explicit themes dealing with trans issues, exploring one woman’s exploration of self and securing the identity she’s always wanted through the lens of a lurid soap opera trading in stereotypes. It’s a lot of movie to digest, and while it feels entirely sincere in every one of its strange creative decisions, it’s also the kind of movie whose tone can invite snickers or derision, like the sex change clinic where a heavily bandaged chorus repeats words like, “vagioplastia” and “penoplastia.” It’s a movie with extreme feelings to go along with its extreme plot turns, but the whole movie feels like it’s trying to settle on a better calibrated wavelength of melodrama.

I think this could have been significantly improved by director/co-writer Jacques Audiard (Rust and Bone, A Prophet) had he embraced more of the movie’s outlandish reality breaking through. Too few of the musical numbers actually do something more than witness someone singing. The opening number, one of the best, involves Rita trying to compose a defense through the streets of Mexico City, while a crowd sweeps around her, often stopping to chime in as an impromptu chorus, sometimes setting up props for her use. It’s a great kickoff, the energy crackling, and I was looking forward to what the rest of the movie could offer. There’s only one other musical number that recreates this significant energy and engagement, a fundraising dinner for Emilia’s organization amongst the powerful members of society. While Emilia speaks at a podium, Rita struts around the floor, sashaying between the tables, and informing the audience about all the dirty deeds and skeletons of the assembled muckety-mucks. She’s literally manhandling the frozen participants, dancing atop their tables in defiance, and it’s a magnificent moment because of how it breaks from our reality to lean into the storytelling potential of musicals. These sequences work so well that it’s flabbergasting that Audiard has, essentially, settled for far less creatively for too much of his movie’s staging. The big Selena Gomez song is just her listlessly singing to the camera while shifting her weight while standing, like the laziest music video of her career. Why tease the audience with the crazy heights as a musical if you’re unwilling?

And now let’s tackle the music, which to my ears was too often rather underwhelming.It sounds like temp music that was intended to be replaced and never was. It’s lacking distinct personality, catchy or memorable melodies, anthems and themes, the things that make musicals enjoyable. The best songs also happen to be the best staged sequences, both involving Rita. These songs have a different vivacious energy by incorporating a hip-hop style of syncopation. “El Mar,” the song during the fundraising dinner, offers an infectious chorus adding extra percussive elements like people slamming fists down onto tables, listening to plates and glasses rattle. These are the moments that enliven a musical and convey its style and panache. Alas, too many of the songs lack that vitality, and can best be described as blandly competent and too readily forgettable.

It’s a shame because Saldana is giving her finest screen performance to date (to be fair, I never watched her Nina Simone biopic). The actress best known for being the strong warrior in sci-fi franchises like Avatar, Guardians of the Galaxy, and Star Trek plays an intriguing character with a rising fire of purpose and paranoia. Early on. Rita is ambitious but unhappy, practically dowdy in appearance, and she begins to come alive under her new role for Emilia. Saldana is electric as she sings and dances and slips effortlessly between Spanish and English, possibly to her first Oscar nomination. She’s the standout, which is slightly strange considering the role of Emilia Perez should be the breakout. Gascon, a trans actress, is quite good in such an outsized role, and gets to play her pre-transitioned identity as well under gobs of masculine makeup and tattoos. The fault isn’t with Gascon’s performance, the issue is that her character has such amazing potential but feels criminally underdeveloped. There is a world of issues of self-identity, culture, repression, shame, anger, jealousy, desire, to name but a few, that could be richly explored from the perspective of the leader of a deadly gang wanting to become a woman. The character is left too inscrutable for my tastes, leaving behind so much unobserved drama. As a result, even though the movie is literally named after her, Emilia Perez feels like a projection more than a character, and if that was indeed the point, then we needed more conflict about that friction.

Emilia Perez is a lot of things all at once; campy, ridiculous, sincere, crazy. It’s messy but it’s an admirably ambitious mess, one that even the faults can be the unexpected charms for someone else. I didn’t fall in love with this genre-bending experiment, although I found portions to be fascinating and others to be confounding. I don’t even think the musical aspects were finely integrated and explored, and so they feel like more of a gimmick, a splashy attempt to marry the high-art of musical theater with the perceived lower-art of grisly crime thrillers and melodrama. It earns marks for daring but the execution is haphazard and scattershot at best. There are moments that elevate the material, where the musical elements feel confidently integrated and supported with the dramatic sequence of events, providing an unexpected and rousing response. However, those moments are few and far between, and the absence only further cements what could have been. Emilia Perez might be your worst movie of the year, a grave miscalculation in tone and storytelling, or it might be a transporting and wild experience, one that can lock up multiple Academy Award combinations for its artistic bravura, a middle-aged Frenchman telling the story of trans empowerment through the guise of a Spanish-speaking musical framework. It sounds like so much and yet paradoxically I was left disappointed that it wasn’t more.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Joker: Folie à Deux (2024)

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think actually work as musicals.

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think actually work as musicals.

Joker 2, which I will be referring to it as for the duration of this review mostly because I don’t want to type out Folie a Deux, and not due to some explicit dislike of the French, is a fascinating misfire that comes across as downright disdainful of its audience, its studio, and its very existence. The last time I felt this way from a sequel was 2021’s Matrix Resurrections, another fitfully contemptuous movie that was alienating and self-erasing and also from Warner Brothers. The first Joker movie in 2019 was a surprise hit, grossing over a billion dollars, which meant that the studio wasn’t going to sit idly by and not force a sequel for a movie clearly intended to be one complete movie. While the first movie cost a modest $50 million, the sequel cost close to $200 million, with big pay days for Joaquin Phoenix, Lady Gaga, and co-writer/director Todd Phillips, who I have to remind you, dear reader, was actually nominated for a Best Director Oscar in 2019. Having gotten their paydays, it feels like Phillips and his collaborators have set out to scorch all available earth, going so far as to even insult fans of the earlier movie. Add the bizarre musical factor, and I don’t know how else to describe Joker 2 but as an alienating and miserable protracted exercise in self-immolating artistic hubris. It’s so rare to see this level of artistic clout used to proverbially stick a finger in the eye of every fan and studio exec who might have hoped there could be something of value here.

Let’s tackle the plot first, as we pick up months after the events of the 2019 film where lowly Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) is being tried for the murders he committed, most famously on a TV talk show where he debuted his stand-up comedian persona as Joker in full regalia. There’s an (un)healthy contingent of the rabble that idolize Arthur, finding the Joker to be some kind of mythic hero of class-conscious revolution, pointing out how society is failing all the little guys getting crushed by the rich and powerful and privileged, like that dead Wayne family. One of those fans is Lee (Gaga), a.k.a. Harleen Quinzel, a disturbed young woman obsessed with getting closer to Arthur, and he is extremely appreciative of the fawning attention. The defense case hinges upon whether or not Arthur was acting on his own accord or had a psychotic break, disassociating as “Joker,” and thus cannot be held accountable for the murders. Except it seems “Joker” is all the people of Gotham want to talk about, whether it’s the media or the public, and what about poor lonely Arthur?

Let’s tackle the plot first, as we pick up months after the events of the 2019 film where lowly Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) is being tried for the murders he committed, most famously on a TV talk show where he debuted his stand-up comedian persona as Joker in full regalia. There’s an (un)healthy contingent of the rabble that idolize Arthur, finding the Joker to be some kind of mythic hero of class-conscious revolution, pointing out how society is failing all the little guys getting crushed by the rich and powerful and privileged, like that dead Wayne family. One of those fans is Lee (Gaga), a.k.a. Harleen Quinzel, a disturbed young woman obsessed with getting closer to Arthur, and he is extremely appreciative of the fawning attention. The defense case hinges upon whether or not Arthur was acting on his own accord or had a psychotic break, disassociating as “Joker,” and thus cannot be held accountable for the murders. Except it seems “Joker” is all the people of Gotham want to talk about, whether it’s the media or the public, and what about poor lonely Arthur?

If I had to fathom a larger thematic point, it feels like Phillips is trying to put our media ecosphere and comics fandom into judgement. He’s pointing to his movie and saying, “You wouldn’t have cared nearly as much about this project had it just been some other spooky, disturbed man losing his sanity and lashing out. You only care because he would eventually become the notorious Batman villain or lore, and that’s why you’re back.” Well, to answer succinctly, of course. When your movie’s conceptual conceit is all about providing a gritty back-story for a famous supervillain, don’t be surprised when there’s more attention and interest. This would be the same if Phillips had made a searing drama about teenage nihilism and easy access to guns and then called it Dylan Klebold: The Movie (one half of the Columbine killers, if you forgot). Stripping back layers to provide setup for a famous killer will always generate more interest than if it was some fictional nobody. It’s an accessible starting point for a viewer and there’s an innate intrigue in trying to answer the tantalizing puzzle of how terrible people got to be so terrible.

I found the 2019 movie to be a mostly interesting experiment without too much to say with its larger social commentary. It felt like Phillips relied a bit too heavily on that assumed familiarity with the character to fill in the missing gaps of his storytelling. It was a proof of concept for that proved successful beyond measure (a billion dollars, 11 Oscar nominations, including THREE for Phillips). This time, Phillips is taking even less subtlety with his blowtorch as he actively annihilates whatever audiences may have enjoyed or appreciated in the first movie.

And in order to fully appreciate the scope of this movie’s active distaste for its own existence, I’ll be treading into some major spoilers, so jump forward a paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled, dear reader. The conclusion of this sequel is a miserable succession of hits that degrades Arthur. At the conclusion of the 2019 original, at least you could say he was becoming a more realized version of what he wanted to be, albeit a disturbed murderer, but one who became the face of a revolution and gained a legion of adoring followers that he desperately craved. At the end of Joker 2, Arthur pathetically admits in his trial there is no alternate Joker persona and that he’s just a sad loser. Then Lee admits that she was only ever interested in “Joker” and wants nothing to do with Arthur the sad loser. And then upon returning to prison, another inmate confronts Arthur, apparently feeling personally betrayed for whatever reason. This irate prisoner stabs Arthur to death and then laughs in a corner, slicing a smile into the sides of his mouth, Heath Ledger-style. The movie literally ends with Arthur laying in a pool of his own blood, staring dead-eyed into the camera, with Phillips metaphorically painting emphatically at his corpse and defiantly saying, “Look, he’s not even the Joker now! Do you still care? Do you?” These movies were designed to be the untold history of the man who would be Joker, and they now have ended up being four hours about the guy whose idea maybe inspired a criminal lunatic to improve upon what he felt was another guy’s brand. What’s even the point? We followed two movies about the guy who isn’t the Joker? Seems pretty definitive there won’t be a third Arthur Fleck movie, as there’s nothing left for Phillips and his anarchic collaborators to demolish to smithereens.

And in order to fully appreciate the scope of this movie’s active distaste for its own existence, I’ll be treading into some major spoilers, so jump forward a paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled, dear reader. The conclusion of this sequel is a miserable succession of hits that degrades Arthur. At the conclusion of the 2019 original, at least you could say he was becoming a more realized version of what he wanted to be, albeit a disturbed murderer, but one who became the face of a revolution and gained a legion of adoring followers that he desperately craved. At the end of Joker 2, Arthur pathetically admits in his trial there is no alternate Joker persona and that he’s just a sad loser. Then Lee admits that she was only ever interested in “Joker” and wants nothing to do with Arthur the sad loser. And then upon returning to prison, another inmate confronts Arthur, apparently feeling personally betrayed for whatever reason. This irate prisoner stabs Arthur to death and then laughs in a corner, slicing a smile into the sides of his mouth, Heath Ledger-style. The movie literally ends with Arthur laying in a pool of his own blood, staring dead-eyed into the camera, with Phillips metaphorically painting emphatically at his corpse and defiantly saying, “Look, he’s not even the Joker now! Do you still care? Do you?” These movies were designed to be the untold history of the man who would be Joker, and they now have ended up being four hours about the guy whose idea maybe inspired a criminal lunatic to improve upon what he felt was another guy’s brand. What’s even the point? We followed two movies about the guy who isn’t the Joker? Seems pretty definitive there won’t be a third Arthur Fleck movie, as there’s nothing left for Phillips and his anarchic collaborators to demolish to smithereens.

When I heard that Joker 2 was going to be a musical, I actually got a little excited, as it felt like Phillips was going to try something very different. Now the curse of many modern movie musicals is trying to come up with an excuse for why the world is exploding in song and dance, like 2002’s Chicago implying it’s all in Roxy’s vivid imagination. Joker 2 takes a similar approach, conveying that when Arthur is breaking out into song that it’s a mental escape for him, that it’s not actually happening in his literal reality. Except… why are there sequences outside Arthur’s point of view where other characters are breaking into song, notably Lee? Is this perhaps a transference of Arthur’s perspective, like he’s imagining them on the outside joining him in tandem? The concept fits with his desperate desire to forge meaningful human connections with people that see him for who he is, and having another character harmonize with him provides a fantasy of validation. Except… there’s no meaningful personal connection between Arthur and the allure of movie musicals. It’s not like he or his domineering mother, the same woman he murdered if you recall, were lifelong fans of musicals and their magical possibilities. It’s not like 2001’s Dancer in the Dark where our lonely protagonist dreamed of being in a movie musical as an escape from her depressing life of exploitation and poverty. It just happens, and you’re listening to Phoenix’s off-putting, gravelly voice straining to recreate classics like “For Once in My Life” and “When You’re Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You).” It’s also a criminal waste of a perfectly game Gaga.

Phillips’ staging of his musical numbers are so lifelessly devoid of energy and imagination. Most of our musical numbers are merely in the same setting without any changes besides now one, or occasionally two, characters are singing. There’s one number that becomes a dance atop a roof, and several duets that appear like a hammy Sonny and Cher 1970s variety TV show, and that’s all you’re getting folks in the realm of visual escapism and choreography. In retrospect, it feels like the musical aspect of the sequel might have been a manner to pad it to feature-length, adding 16 performances and over 40 minutes of singing old standards. There’s a good deal of repetition with this sequel, as much of the plot is restating the events of the first film; that’s essentially what the courtroom drama facilitates as it trots out all the previous characters to recap their roles and point an accusatory finger back at Arthur.

Phillips’ staging of his musical numbers are so lifelessly devoid of energy and imagination. Most of our musical numbers are merely in the same setting without any changes besides now one, or occasionally two, characters are singing. There’s one number that becomes a dance atop a roof, and several duets that appear like a hammy Sonny and Cher 1970s variety TV show, and that’s all you’re getting folks in the realm of visual escapism and choreography. In retrospect, it feels like the musical aspect of the sequel might have been a manner to pad it to feature-length, adding 16 performances and over 40 minutes of singing old standards. There’s a good deal of repetition with this sequel, as much of the plot is restating the events of the first film; that’s essentially what the courtroom drama facilitates as it trots out all the previous characters to recap their roles and point an accusatory finger back at Arthur.

There is one lone outstanding scene in Joker 2, and it happens to be when Arthur, in full Joker makeup, is cross-examining his old clown entertainer work buddy, Gary Puddles (Leigh Gill). Arthur admonishes Gary, saying he spared him, and Gary painfully articulates how hellish his life has been as witness to Arthur’s killing, how little he sleeps, how it torments him and makes him so afraid. For a brief moment, this character shares his vulnerability and the lingering trauma that Arthur has inflicted, and it appears like Arthur is wounded by this realization, until he settles back into the persona he’s trying to put forward, the “face” for his defense, and goes back to ridiculing Gary’s name and turning the cross-examination into an awkward standup session. It’s a palpable moment that feels raw and surprising and empathetic in a way the rest of the movie fails to.

Is there anything else to celebrate with Joker 2’s troubled existence? The cinematography by Lawrence Sher can be strikingly beautiful, especially with certain shot compositions and lighting contrasts. It makes it all the more confounding when almost all the musical numbers lack visual panache. The Oscar-winning composer returns and while still atmospheric and murky the score is also far less memorable and fades too often into the background, like too many of the technical elements. Joker 2 has plenty of talented people involved in front of and behind the camera, but to what end? What are all their troubles adding up to? It practically feels like a very expensive practical joke, on the audience, on the studio, and that is genuinely fascinating. However, it doesn’t make the end product any better, and the film’s transparent contempt sours every minute of action. Even if you were a super fan of Joker or morbidly curious, steer clear of Folie a Deux, a folly on all of us.

Nate’s Grade: D

Daddio (2024)

A lengthy conversation playing out in real-time between two strangers who open up to one another over the course of one taxi drive from the airport. If it feels Richard Linklater-adjacent, that’s because writer/director Christy Hall (I Am Not Okay With This) has certainly been influenced by the chatty likes of Linklater, as she sticks us in the cab for the entire duration of that 90-minute ride and movie. We have Dakota Johnson as the fare, a woman returning home after visiting family with secrets and shame that she’ll reveal over the course of this cab ride. We have Sean Penn as the cab driver, a seen-it-all cynic who keeps pushing for more answers and conversation from his passenger. The problem with movies based solely around conversations is that the conversation has to be mesmerizing, exhibiting great care to impart artful and authentic character details that make us reconsider these people, and hopefully provide challenges to preconceived norms and ingrained perspectives that can foster reflective growth. Nobody wants to watch a movie about a trivial conversation over 90 minutes. The problem with Daddio is that it’s not really a two-way conversation; Penn acts more as an interrogator, slowly chipping away at the layers that Johnson’s young woman feels comfortable presenting publicly. The dialogue is fine but unremarkable, eschewing overly stylized verbosity for something more natural, but even with that choice the details we are granted are clumsy and minimal. Get ready for lots of protracted pauses awaiting texting replies. The acting is fairly solid throughout, especially Johnson since it is a whole showcase for her in that backseat. If we’re going to be riding shotgun on a 90-minute conversation, I guess I’m just looking for far more scintillating details, whether it’s from the characters, their conflicts, or just their gregarious dialogue. If we’re stuck with two people, let’s be stuck with two people we actually might want to share a cab with.

A lengthy conversation playing out in real-time between two strangers who open up to one another over the course of one taxi drive from the airport. If it feels Richard Linklater-adjacent, that’s because writer/director Christy Hall (I Am Not Okay With This) has certainly been influenced by the chatty likes of Linklater, as she sticks us in the cab for the entire duration of that 90-minute ride and movie. We have Dakota Johnson as the fare, a woman returning home after visiting family with secrets and shame that she’ll reveal over the course of this cab ride. We have Sean Penn as the cab driver, a seen-it-all cynic who keeps pushing for more answers and conversation from his passenger. The problem with movies based solely around conversations is that the conversation has to be mesmerizing, exhibiting great care to impart artful and authentic character details that make us reconsider these people, and hopefully provide challenges to preconceived norms and ingrained perspectives that can foster reflective growth. Nobody wants to watch a movie about a trivial conversation over 90 minutes. The problem with Daddio is that it’s not really a two-way conversation; Penn acts more as an interrogator, slowly chipping away at the layers that Johnson’s young woman feels comfortable presenting publicly. The dialogue is fine but unremarkable, eschewing overly stylized verbosity for something more natural, but even with that choice the details we are granted are clumsy and minimal. Get ready for lots of protracted pauses awaiting texting replies. The acting is fairly solid throughout, especially Johnson since it is a whole showcase for her in that backseat. If we’re going to be riding shotgun on a 90-minute conversation, I guess I’m just looking for far more scintillating details, whether it’s from the characters, their conflicts, or just their gregarious dialogue. If we’re stuck with two people, let’s be stuck with two people we actually might want to share a cab with.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Didi (2024)