Monthly Archives: December 2024

The Bikeriders (2024)

For a four-year period, writer/director Jeff Nichols is a filmmaker who appeared on my Best of the Year list three years, including making my top movie of 2011, Take Shelter. He’s a filmmaker I highly prize, so an eight-year gap from Nichols is an extended leave that makes me personally sad, though his latest movie, The Bikeriders, was delayed by a year after Disney decided to sell it rather than release it for the 2023 awards season. It’s a pretty straightforward drama about a Chicago motorcycle club in the 1960s. It’s all about a group of men that really don’t know how to express their feelings, so it comes out as drinking and fighting and general rebellion against outside authority. These social outsiders find kinship under the leadership of Johnny (Tom Hardy), an unstable man with his own code of honor and retribution. Our narrator is Kathy (Jodie Comer), a plucky woman who falls for a reckless biker, Benny (Austin Butler). There are plenty of interesting moments and sequences, like the rejection of wannabe new members too eager for approval for institutional violence. The changes the club undergoes through the mid 1970s are interesting, especially as the rules of the club begin to fray with the influx of new members and drug addictions, and the challenges to leadership we know will eventually end in tragedy and a betrayal of what the club was intended to be. Regardless, it feels like the movie has all the authentic texture and period details right but is missing a stronger sense of story. It’s more a collage of moments that doesn’t add up to a much better understanding of the three main characters. It’s more like a mood mosaic than engrossing drama, so if you have a general interest in retro motorcycle culture or the time periods, then maybe it will cover the absences in character. I found The Bikeriders to be a good-looking coffee-table book of a movie, more recreation than investment.

For a four-year period, writer/director Jeff Nichols is a filmmaker who appeared on my Best of the Year list three years, including making my top movie of 2011, Take Shelter. He’s a filmmaker I highly prize, so an eight-year gap from Nichols is an extended leave that makes me personally sad, though his latest movie, The Bikeriders, was delayed by a year after Disney decided to sell it rather than release it for the 2023 awards season. It’s a pretty straightforward drama about a Chicago motorcycle club in the 1960s. It’s all about a group of men that really don’t know how to express their feelings, so it comes out as drinking and fighting and general rebellion against outside authority. These social outsiders find kinship under the leadership of Johnny (Tom Hardy), an unstable man with his own code of honor and retribution. Our narrator is Kathy (Jodie Comer), a plucky woman who falls for a reckless biker, Benny (Austin Butler). There are plenty of interesting moments and sequences, like the rejection of wannabe new members too eager for approval for institutional violence. The changes the club undergoes through the mid 1970s are interesting, especially as the rules of the club begin to fray with the influx of new members and drug addictions, and the challenges to leadership we know will eventually end in tragedy and a betrayal of what the club was intended to be. Regardless, it feels like the movie has all the authentic texture and period details right but is missing a stronger sense of story. It’s more a collage of moments that doesn’t add up to a much better understanding of the three main characters. It’s more like a mood mosaic than engrossing drama, so if you have a general interest in retro motorcycle culture or the time periods, then maybe it will cover the absences in character. I found The Bikeriders to be a good-looking coffee-table book of a movie, more recreation than investment.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Nightbitch (2024)

Motherhood can be a real bitch, right? That’s the lessons for Nightbitch, a bizarre movie that juggles high-concepts and tones like a struggling new mother juggling time. Based on the novel by Rachel Yoder, Amy Adams plays Mother (yes, that’s how she’s credited), an artist who chose to become a stay-at-home mother to her two-year-old son, and her life has become an endless stream of days appeasing a small tyrant who she also unconditionally loves. Early on, Adams uncorks an imaginary monologue about demystifying the glamour of motherhood and the guilt she feels about not finding every tantrum and bowel movement a thing of bronze-worthy beauty. She’s grappling with significant changes, and that’s even before she thinks she’s turning into a dog. I can find thematic connection with motherhood and body horror, as our protagonist feels that she no longer recognizes her body, that she feels a lack of direction and agency in a life that no longer feels hers. The added body horror of transformation makes sense, but this element seems so extraneous that I wished the movie had exorcised it and simply stuck with its unsparing examination of parenthood. You would think a woman believing she is becoming a dog would dominate her life. The ultimate life lessons of the movie are rather trite: assert yourself, establish a balance to have it all, and fellas, did you know that being a stay-at-home parent is actually hard work? There are too many half-formed elements and plot turns that don’t feel better integrated, like flashbacks interwoven with Mother’s mother, not credited as “Grandmother,” as a repressed Mennonite in a closed community who disappeared for stretches. There’s also a few curious reveals relating to Mother’s perception of others that are unnecessary and obtusely mysterious for no real added value (“Why that library book died forty years ago….”). Adams is blameless and impressively throws herself into the demanding roll, going full canine with gusto as she trots on all fours and eats out of bowls. The problem is that all the dog material feels a little too silly when realized in a visual medium rather than a symbol of freedom and rebellion. Nightbitch is more bark than bite, and I’d advise viewers looking for an unflinching portrayal of motherhood to watch Tully instead and, if desired, pet your household dog at home to replicate Nightbbitch but better.

Motherhood can be a real bitch, right? That’s the lessons for Nightbitch, a bizarre movie that juggles high-concepts and tones like a struggling new mother juggling time. Based on the novel by Rachel Yoder, Amy Adams plays Mother (yes, that’s how she’s credited), an artist who chose to become a stay-at-home mother to her two-year-old son, and her life has become an endless stream of days appeasing a small tyrant who she also unconditionally loves. Early on, Adams uncorks an imaginary monologue about demystifying the glamour of motherhood and the guilt she feels about not finding every tantrum and bowel movement a thing of bronze-worthy beauty. She’s grappling with significant changes, and that’s even before she thinks she’s turning into a dog. I can find thematic connection with motherhood and body horror, as our protagonist feels that she no longer recognizes her body, that she feels a lack of direction and agency in a life that no longer feels hers. The added body horror of transformation makes sense, but this element seems so extraneous that I wished the movie had exorcised it and simply stuck with its unsparing examination of parenthood. You would think a woman believing she is becoming a dog would dominate her life. The ultimate life lessons of the movie are rather trite: assert yourself, establish a balance to have it all, and fellas, did you know that being a stay-at-home parent is actually hard work? There are too many half-formed elements and plot turns that don’t feel better integrated, like flashbacks interwoven with Mother’s mother, not credited as “Grandmother,” as a repressed Mennonite in a closed community who disappeared for stretches. There’s also a few curious reveals relating to Mother’s perception of others that are unnecessary and obtusely mysterious for no real added value (“Why that library book died forty years ago….”). Adams is blameless and impressively throws herself into the demanding roll, going full canine with gusto as she trots on all fours and eats out of bowls. The problem is that all the dog material feels a little too silly when realized in a visual medium rather than a symbol of freedom and rebellion. Nightbitch is more bark than bite, and I’d advise viewers looking for an unflinching portrayal of motherhood to watch Tully instead and, if desired, pet your household dog at home to replicate Nightbbitch but better.

Nate’s Grade: C

Nickel Boys (2024)

This might be the most immersive and biggest directorial swing of the year. Director/co-writer RaMell Ross adapts the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead about a reform school for juveniles more like a prison during the Civil Rights era. Ostensibly, the Nickel Academy is an institution that is meant to teach moral lessons and responsibility through outdoor labor. In reality, it’s a school that benefits from labor exploitation and has no intention of fulfilling its promise that students can possibly leave before they turn eighteen. This is even worse for African-Americans, as the school is also segregated and the students have to endure the racism of the administrators and other white juvenile delinquents who still want to feel superior to somebody. It’s a cruel setting destined to spark risable outrage, especially knowing that our main character, Elwood Curtis, is a victim of profiling and being in the wrong place at the wrong time, a star student selected to take college classes at an HBCU. The big artistic swing of Nickel Boys is the choice to tell the entire movie through first-person perspective, with the camera functioning as our protagonist’s eyes and ears. As the camera moves, it is us moving. It makes the movie intensively immersive, but I had some misgivings about this storytelling gimmick. It limits the resonance of the central performance as we can’t see the actor and his expressions and emotions, which I found frustrating. Ross also decides to do this same trick twice with a second character who befriends Elwood. Now we can see more of our main character, through this other person’s eyes occasionally, but it’s also like having to re-learn the visual vocabulary, and switching from viewpoints was distracting for the immersion and to recall whose eyes were whose at any moment. There’s also flash-forwards to adult Elwood that only served to muddle the tension. There’s enough genuine drama in this setting that I wish Nickel Boys might have been a more traditionally-made drama. Still, it’s a fine movie, but the aspect that will make it stand out the most is also what I feel that holds it back for me from being more profoundly affecting.

This might be the most immersive and biggest directorial swing of the year. Director/co-writer RaMell Ross adapts the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Colson Whitehead about a reform school for juveniles more like a prison during the Civil Rights era. Ostensibly, the Nickel Academy is an institution that is meant to teach moral lessons and responsibility through outdoor labor. In reality, it’s a school that benefits from labor exploitation and has no intention of fulfilling its promise that students can possibly leave before they turn eighteen. This is even worse for African-Americans, as the school is also segregated and the students have to endure the racism of the administrators and other white juvenile delinquents who still want to feel superior to somebody. It’s a cruel setting destined to spark risable outrage, especially knowing that our main character, Elwood Curtis, is a victim of profiling and being in the wrong place at the wrong time, a star student selected to take college classes at an HBCU. The big artistic swing of Nickel Boys is the choice to tell the entire movie through first-person perspective, with the camera functioning as our protagonist’s eyes and ears. As the camera moves, it is us moving. It makes the movie intensively immersive, but I had some misgivings about this storytelling gimmick. It limits the resonance of the central performance as we can’t see the actor and his expressions and emotions, which I found frustrating. Ross also decides to do this same trick twice with a second character who befriends Elwood. Now we can see more of our main character, through this other person’s eyes occasionally, but it’s also like having to re-learn the visual vocabulary, and switching from viewpoints was distracting for the immersion and to recall whose eyes were whose at any moment. There’s also flash-forwards to adult Elwood that only served to muddle the tension. There’s enough genuine drama in this setting that I wish Nickel Boys might have been a more traditionally-made drama. Still, it’s a fine movie, but the aspect that will make it stand out the most is also what I feel that holds it back for me from being more profoundly affecting.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Brutalist (2024)

The indie sensation of the season is an ambitious throwback to meaty movie-going of the auteur 1970s, telling an immigrant’s expansive tale, and at an epic length of 3 hours and 30 minutes, and an attempt to tell The Immigrant Story, and by that we mean The American Story. It’s a lot for any movie to do, and while The Brutalist didn’t quite rise to the capital-M “masterpiece” experience so many of my critical brethren have been singing, it’s still a very handsomely made, thoughtfully reflective, and extremely well-acted movie following one man trying to start his life over. Adrien Brody plays Laszlo Toth, A Jewish-Hungarian survivor of the Holocaust who relocates to Pennsylvania in 1947. He starts work delivering furniture before getting a big break redesigning a rich man’s library as a surprise birthday gift that doesn’t go over well. Years later, that same rich man, Harrison Lee (Guy Pearce), wants to seek out Laszlo because his library has become a celebrated example of modern architecture. He proposes Laszlo design a grandiose assembly that will serve as a community center, chapel, library, gymnasium, and everything to everyone, standing atop a hill like a beacon of twentieth-century civilization. Everything I’ve just written is merely the first half of this massive movie, complete with an old-fashioned fifteen-minute intermission.

The second half is about crises professional and personal for Laszlo; the meddling and compromises and shortfalls of his big architectural project under the thumb of Harrison, and finding and bringing his estranged wife (Felicity Jones) to America and dealing with the aftermath of their mutual trauma. I was never bored with writer/director Brady Crobett’s (Vox Lux) movie, which is saying something considering its significant length. The scenes just breathe at a relaxed pace that feels more like real life captured on film. The confidence and vision of the movie becomes very clear, as Corbett painstakingly takes his time to tell his sprawling story on his terms. I can appreciate that go-for-broke spirit, and The Brutalist has an equal number of moments that are despairing as they are enlightening. I was more interested in Laszlo’s relationship with his wife, now confined to a wheelchair. There are clear emotional chasms between them to work through, having been separated at a concentration camp, but there is a real desire to reconnect, to heal, and to confront one another’s challenges. It’s touching and the real heart of the movie, and it easily could have been the whole movie. The rest, with Laszlo butting heads against moneymen to secure the integrity of his vision, is an obvious allegory for filmmaking or really any artist attempt to realize a dream amidst the naysayers. The acting is terrific across the board, with Brody returning to a form he hasn’t met in decades. Maybe his career struggles since winning the Best Actor Oscar in 2003 have only helped imbue this performance with a lived-in quality of a soul-searching artist. Pearce is commanding and infuriating as the symbol of America’s ego and sense of superiority. The musical score is unorthodox but picks up a real sense of momentum like a locomotive, thrumming along at a building pace of progress. The only real misstep is an unnecessary epilogue that spells out exactly how you should feel about the movie rather than continuing the same respect and trust for its patient audience. The Brutalist is an intimidating movie and one best to chew over or debate its portrayal of the American Dream, and while not all of its artistic swings connect, the sheer ambition, fortitude, and confident execution of the personal and the grandiose is worth celebrating and elevating.

Nate’s Grade: B

Babygirl (2024)

It’s so rare to see erotic dramas with the kind of pedigree, and set up for potential awards buzz, of Babygirl, and I think that’s because they’re a little hard to take seriously (see the ridiculous and tone-deaf Deep Water for further proof). What distinguishes the artistic erotic drama from the tawdry erotic drama will be a perhaps invisible line. Still, it’s rare for an actress of Nicole Kidman’s caliber, and let’s also be frank -her age- to headline an erotic drama, so that naturally draws some intrigue and eyeballs. Babygirl follows a familiar premise of taboo desires at the expense of domestic upheaval, but where it goes makes it ultimately feel like an unsatisfying morality tale.

It’s so rare to see erotic dramas with the kind of pedigree, and set up for potential awards buzz, of Babygirl, and I think that’s because they’re a little hard to take seriously (see the ridiculous and tone-deaf Deep Water for further proof). What distinguishes the artistic erotic drama from the tawdry erotic drama will be a perhaps invisible line. Still, it’s rare for an actress of Nicole Kidman’s caliber, and let’s also be frank -her age- to headline an erotic drama, so that naturally draws some intrigue and eyeballs. Babygirl follows a familiar premise of taboo desires at the expense of domestic upheaval, but where it goes makes it ultimately feel like an unsatisfying morality tale.

Kidman plays Romy, a powerful tech CEO suffering from a lack of spark in her love life. She loves her husband (Antonio Banderas), her three teenage girls, and the life she’s built for herself, but she also needs to masturbate if she ever wants to be physically satisfied. Along comes a lanky hunk by the name of Samuel (Harris Dickinson) as an intern at her company and immediately makes her feel hot and bothered. He’s direct and wants to tell her what to do, and the excitement Romy feels makes her question how far she’s willing to go and what she’s willing to risk to chase her passions.  Babygirl is another rich person’s fantasy romance where a character risks losing their family on a fling, and usually these stories only go so many ways, primarily with the protagonist regretting their affair and learning some kind of lesson from the ordeal. For a formula meant to inspire titillation and transgression, these movies can be, at their core, very moralistic and conservative. There are so many movies that prominently feature cheating only for the person to realize how much they were taking for granted what they had all along. So many of these wayward participants don’t feel like they have lost something by the end even after risking their relationships, so the conclusion of these movies seems to be a facile “don’t do that again” lesson of sowing one’s oats. It strikes me as ironic that these stories are about untamed passions but they end so dispassionately. For the first half of Babygirl, I was questioning where this movie could lead: would the husband kill his wife’s lover and through the shared disposal of his body bring them closer together? Would it be revealed that Samuel was a stalker who manipulated his way into Romy’s life? Was her husband secretly behind this strapping young lad coming into her path and trying to provide her that spark of danger but in an unknowingly controlled environment? The eventual path of Babygirl is probably the most realistic path and yet it’s rather dramatically lacking and insert. Ultimately, the movie’s message seems to coalesce around accepting your desires and being open about sharing them; however, the proceeding movie doesn’t feel like a meaningful road to that cozy conclusion.

Babygirl is another rich person’s fantasy romance where a character risks losing their family on a fling, and usually these stories only go so many ways, primarily with the protagonist regretting their affair and learning some kind of lesson from the ordeal. For a formula meant to inspire titillation and transgression, these movies can be, at their core, very moralistic and conservative. There are so many movies that prominently feature cheating only for the person to realize how much they were taking for granted what they had all along. So many of these wayward participants don’t feel like they have lost something by the end even after risking their relationships, so the conclusion of these movies seems to be a facile “don’t do that again” lesson of sowing one’s oats. It strikes me as ironic that these stories are about untamed passions but they end so dispassionately. For the first half of Babygirl, I was questioning where this movie could lead: would the husband kill his wife’s lover and through the shared disposal of his body bring them closer together? Would it be revealed that Samuel was a stalker who manipulated his way into Romy’s life? Was her husband secretly behind this strapping young lad coming into her path and trying to provide her that spark of danger but in an unknowingly controlled environment? The eventual path of Babygirl is probably the most realistic path and yet it’s rather dramatically lacking and insert. Ultimately, the movie’s message seems to coalesce around accepting your desires and being open about sharing them; however, the proceeding movie doesn’t feel like a meaningful road to that cozy conclusion.

There’s a dramatically rich idea that could have been explored more maturely, namely that this woman has sacrificed her own physical pleasure for her career achievement. During one awkward night, Romy admits to her husband that over the decades of their relationship that he has never made her climax. His manly ego is bruised severely and Romy tries to wave away the statement, but the movie only seems to use this detail as further establishment for the motivation to have an affair. Director/writer Halina Reijn (Bodies Bodies Bodies) sets this up within the very first shot of the movie, with Romy finishing having sweaty sex with her husband only to finish by herself with the help of Internet pornography. Right away we know her husband isn’t doing it for her. There’s one moment where Romy explains that she feels like her desires are degrading and self-destructive, but she won’t share them with her husband. She tries to guide him there, planting a pillow over her head to cover her sight to facilitate her imagination, but it makes him feel uncomfortable to continue (“I feel like a villain”). There’s an interesting exploration of keeping passion stoked in a long-standing relationship where inertia can settle in, but the ultimate revelation is rather pat and all-too familiar: communicate more. Thanks, movie. So much of the movie is built around what Romy learns from how far she goes, but what do we learn about Samuel too? He’s kept a frustrating blank of a figure, more catalyst than fully developed character. If he’s ultimately just the excuse to push her out of her comfort zone, did he have to be this boring even with his kinks?  Will you find Babygirl sexy? I don’t know. It primarily trades in dominance/submissive dynamics, and the director keeps her camera’s gaze on the pursuit of feminine pleasure rather than closeups of pert anatomical parts. The sequences where Samuel orders Romy around played more unintentionally comical to me rather than decisively arousing, especially moments like him forcing her to eat out of his hand like a dog. I can understand being in such a high-powered job of constant decision-making might make a fantasy of giving up control and agency seem appealing, but this isn’t really explored in the movie. I can also understand the shame of feeling like your hidden desires might be too embarrassing to share with your partner, but this isn’t fully explored either. For all its heavy breathing and sultry glances, the movie feels far more clinical than passionate. The sensation I felt the most was a lulling curiosity that ultimately went unmet. Your mileage may vary.

Will you find Babygirl sexy? I don’t know. It primarily trades in dominance/submissive dynamics, and the director keeps her camera’s gaze on the pursuit of feminine pleasure rather than closeups of pert anatomical parts. The sequences where Samuel orders Romy around played more unintentionally comical to me rather than decisively arousing, especially moments like him forcing her to eat out of his hand like a dog. I can understand being in such a high-powered job of constant decision-making might make a fantasy of giving up control and agency seem appealing, but this isn’t really explored in the movie. I can also understand the shame of feeling like your hidden desires might be too embarrassing to share with your partner, but this isn’t fully explored either. For all its heavy breathing and sultry glances, the movie feels far more clinical than passionate. The sensation I felt the most was a lulling curiosity that ultimately went unmet. Your mileage may vary.

Babygirl is the kind of movie that critics declare the lead actress being so “brave” to push boundaries at her age, to bare her body in an age bracket that Hollywood finds less-than-desirable. However, Kidman has long been an actress unafraid of the demands of nudity as well as challenging roles, which mitigates the perceived daring of this latest performance. Babygirl is ultimately a disappointing erotic drama that, for me, lacked heat, better character development, and a surprising or insightful plot. In short, Babygirl comes up short where it counts.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Sing Sing (2024)

An uplifting ode to the power of the arts, Sing Sing follows the men of a prison arts program and it’s easily one of the finest films of 2024. We follow the men of the New York prison of the title, lead by Divine G Whitfield (Colman Domingo), a thespian that relishes the dramatic spotlight and the deserved lead of every production. When the next show is suggested as a comedy, Divine G has to accept ceding the spotlight and mentoring a promising but struggling new member (Clarence Maclin) with talent and potential. It’s effectively a “let’s put on a show” formula of old, however, the setting and the weary reflections are what provide the movie its power. All of these men have made mistakes in their respective lives to wind up here, though Divine G maintains his innocence and is preparing his case for a parole board hearing. This program allows them an escape, an opportunity as one puts it to “become human again” While some may scoff at the acting games and costumes, this is sacred ground, a precious oasis for them to discover more about themselves. The sincerity of Sing Sing is wince-inducing. It is beautiful, tender, compassionate, and deeply personal while being very universal. The lived-in details are fantastic and give great authenticity to these men and their stories, wonderfully portrayed by several non-actors making the most of their own spotlights. Domingo (Rustin) is amazing as the proud and generous leader who is ably trying to lift his fellow men up even higher. The film concludes with real footage from the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program, and it’s the fitting culmination for a movie that readily reminds us how restorative and needed the arts are for a fuller sense of who we are.

An uplifting ode to the power of the arts, Sing Sing follows the men of a prison arts program and it’s easily one of the finest films of 2024. We follow the men of the New York prison of the title, lead by Divine G Whitfield (Colman Domingo), a thespian that relishes the dramatic spotlight and the deserved lead of every production. When the next show is suggested as a comedy, Divine G has to accept ceding the spotlight and mentoring a promising but struggling new member (Clarence Maclin) with talent and potential. It’s effectively a “let’s put on a show” formula of old, however, the setting and the weary reflections are what provide the movie its power. All of these men have made mistakes in their respective lives to wind up here, though Divine G maintains his innocence and is preparing his case for a parole board hearing. This program allows them an escape, an opportunity as one puts it to “become human again” While some may scoff at the acting games and costumes, this is sacred ground, a precious oasis for them to discover more about themselves. The sincerity of Sing Sing is wince-inducing. It is beautiful, tender, compassionate, and deeply personal while being very universal. The lived-in details are fantastic and give great authenticity to these men and their stories, wonderfully portrayed by several non-actors making the most of their own spotlights. Domingo (Rustin) is amazing as the proud and generous leader who is ably trying to lift his fellow men up even higher. The film concludes with real footage from the Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA) program, and it’s the fitting culmination for a movie that readily reminds us how restorative and needed the arts are for a fuller sense of who we are.

Nate’s Grade: A

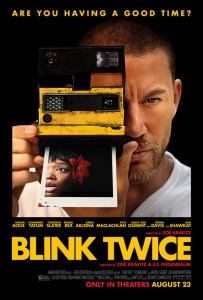

Blink Twice (2024)

Zoe Kravitz’s directorial debut Blink Twice has stayed with me for weeks after I watched it, and with further harrowing revelations coming from the fallout of P. Diddy’s empire of exploitation, it has even more relevance. Think of it as a feminist revenge thriller set on Jeffrey Epstein’s island or a Diddy party. Channing Tatum plays a successful tech bro who hosts lavish getaways for the Wall Street and Silicon Valley elite, where the week is an orgy of food, drink, drugs, and of course sex. We follow Frida (Naomi Ackie), a waitress yearning for the finer things in life, so when Tatum’s rich and famous CEO invites her and her friend to his private island, she’s ecstatic. But everything is not what it seems, and Frida and the other women begin to notice weird clues, that is, when they can remember as time frequently seems to be lost for them. Blink Twice is a twisty, eerie mystery and Kravitz shows real skill at developing tension and suspense, with sequences that had me girding great waves of anxiety. There’s also an eye for style and mood here that makes me feel Kravitz has a real career as a genre director. I don’t think it’s spoilers to say that eventually the surviving women team up together to fight back against their oppressors, and it’s gloriously entertaining, bloody, and table-turning satisfying. The ending is designed to spark debate and controversy, and I enjoy that Kravitz and co-writer E.T. Feigenbaum do not want to make things too tidy, even with their protagonists. The themes here are broad but the execution is exact. There are several moments that stand out to me, from unexpected moments of levity to bold artistic choices that are mesmerizing, like an “I’m sorry” apology that goes through every level. If you’re looking for slickly executed genre thrills with great comeuppance, don’t blink when it comes to with Blink Twice.

Zoe Kravitz’s directorial debut Blink Twice has stayed with me for weeks after I watched it, and with further harrowing revelations coming from the fallout of P. Diddy’s empire of exploitation, it has even more relevance. Think of it as a feminist revenge thriller set on Jeffrey Epstein’s island or a Diddy party. Channing Tatum plays a successful tech bro who hosts lavish getaways for the Wall Street and Silicon Valley elite, where the week is an orgy of food, drink, drugs, and of course sex. We follow Frida (Naomi Ackie), a waitress yearning for the finer things in life, so when Tatum’s rich and famous CEO invites her and her friend to his private island, she’s ecstatic. But everything is not what it seems, and Frida and the other women begin to notice weird clues, that is, when they can remember as time frequently seems to be lost for them. Blink Twice is a twisty, eerie mystery and Kravitz shows real skill at developing tension and suspense, with sequences that had me girding great waves of anxiety. There’s also an eye for style and mood here that makes me feel Kravitz has a real career as a genre director. I don’t think it’s spoilers to say that eventually the surviving women team up together to fight back against their oppressors, and it’s gloriously entertaining, bloody, and table-turning satisfying. The ending is designed to spark debate and controversy, and I enjoy that Kravitz and co-writer E.T. Feigenbaum do not want to make things too tidy, even with their protagonists. The themes here are broad but the execution is exact. There are several moments that stand out to me, from unexpected moments of levity to bold artistic choices that are mesmerizing, like an “I’m sorry” apology that goes through every level. If you’re looking for slickly executed genre thrills with great comeuppance, don’t blink when it comes to with Blink Twice.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Juror #2 (2024)

Clint Eastwood’s possible last movie as a director (the man is 94 years old, people) was buried at the theater through a limited release by its studio, which is a shame because Juror #2 is a fairly solid adult drama with some grueling tension built right in. I was wondering how screenwriter Jonathan Abrams was going to make this premise work, where a recovering alcoholic and expectant father, Justin Kemp (Nicholas Hoult), is impaneled on a jury for a murder case and discovers, over the presentation of evidence, that he might actually be the culprit. That same night, at the same location of where the supposed murder took place, is where Justin thought he hit a deer. What follows is a soul-searching account of one man being torn apart as far as what he should do. Does he let this other man take the blame so Justin can live out his life with his new baby and wife? Or does he come forward and admit his own firsthand knowledge of the events would present a very reasonable doubt for this trial? The movie becomes an extended balancing act of how long Justin can keep this secret and what angles he will work, trying to push the jury one direction or another through persuasive appeals. It’s familiar dramatic territory to anyone who grew up on 12 Angry Men, though with an extra high-concept twist. It’s a fairly straightforward drama that allows the story to take center stage and puts the focus on one man’s personal crisis. The acting is strong all around with Hoult (Nosferatu) being the predicted standout, showing the heavy weight of his guilt wirh every pained expeession. I think the ending does a disservice to the kind of movie that came before it, namely that it should be more definitive in its conclusion and provide a fitting resolution. This isn’t exactly the kind of movie that benefits from prolonged ambiguity, so the abrupt ending feels like a miscalculation and hampers a bit of the ending’s impact. However, Juror #2 is a good squirm session.

Clint Eastwood’s possible last movie as a director (the man is 94 years old, people) was buried at the theater through a limited release by its studio, which is a shame because Juror #2 is a fairly solid adult drama with some grueling tension built right in. I was wondering how screenwriter Jonathan Abrams was going to make this premise work, where a recovering alcoholic and expectant father, Justin Kemp (Nicholas Hoult), is impaneled on a jury for a murder case and discovers, over the presentation of evidence, that he might actually be the culprit. That same night, at the same location of where the supposed murder took place, is where Justin thought he hit a deer. What follows is a soul-searching account of one man being torn apart as far as what he should do. Does he let this other man take the blame so Justin can live out his life with his new baby and wife? Or does he come forward and admit his own firsthand knowledge of the events would present a very reasonable doubt for this trial? The movie becomes an extended balancing act of how long Justin can keep this secret and what angles he will work, trying to push the jury one direction or another through persuasive appeals. It’s familiar dramatic territory to anyone who grew up on 12 Angry Men, though with an extra high-concept twist. It’s a fairly straightforward drama that allows the story to take center stage and puts the focus on one man’s personal crisis. The acting is strong all around with Hoult (Nosferatu) being the predicted standout, showing the heavy weight of his guilt wirh every pained expeession. I think the ending does a disservice to the kind of movie that came before it, namely that it should be more definitive in its conclusion and provide a fitting resolution. This isn’t exactly the kind of movie that benefits from prolonged ambiguity, so the abrupt ending feels like a miscalculation and hampers a bit of the ending’s impact. However, Juror #2 is a good squirm session.

Nate’s Grade: B

Red One (2024)

Is Amazon’s $250 million holiday adventure the harbinger of doom for modern movies as many alarmist film critics have claimed? No. Is it the next great Christmas classic? No. It’s a thoroughly mediocre holiday action movie borrowing heavily from the familiar Marvel movie formula; it strains very hard to be a breezy spectacle and a buddy comedy. There’s a fun concept here about Santa Claus (a buff J.K. Simmons) being kidnapped, but the focus is on the wrong characters. The best segment of Red One is when we’re introduced to Santa’s cranky brother, Krampus (Kristofer Hiivju), a half-demon half-goat creature with excellent practical makeup application and design. The movie feels dangerous and finally intriguing with their history, and it’s here that I realized the best version of Red One would have been one where Santa AND Krampus, two feuding brothers with very different perspectives on how to handle the naughty, are forced to work together to escape their holiday hostage-takers. Alas, the characters we get are The Rock playing a minor variation on the character archetype he’s been grinding into dust for a decade, and Chris Evans as a cynical adult super hacker who needs to learn the true meaning of Christmas. The inclusion of Evans’ character is flimsy and he’s far too annoying to offset whatever advantages he might provide to Santa’s extraction team. The fantasy elements and lore can be fun, like an abominable snowman fight in the tropics, but too many of these elements feel underdeveloped, like the Rock growing big and small for… reasons. Just like how our villain wants to teach the world a lesson in terror… that can be broken by self-reflective apologies. It’s a movie consumed by its many influences. Red One isn’t exactly for little kids, isn’t exactly for adults, and isn’t exactly for teenagers, so who is this for? It’s destined to play in the background and be ignored while holiday naps are had, and to that end, Red One succeeds.

Is Amazon’s $250 million holiday adventure the harbinger of doom for modern movies as many alarmist film critics have claimed? No. Is it the next great Christmas classic? No. It’s a thoroughly mediocre holiday action movie borrowing heavily from the familiar Marvel movie formula; it strains very hard to be a breezy spectacle and a buddy comedy. There’s a fun concept here about Santa Claus (a buff J.K. Simmons) being kidnapped, but the focus is on the wrong characters. The best segment of Red One is when we’re introduced to Santa’s cranky brother, Krampus (Kristofer Hiivju), a half-demon half-goat creature with excellent practical makeup application and design. The movie feels dangerous and finally intriguing with their history, and it’s here that I realized the best version of Red One would have been one where Santa AND Krampus, two feuding brothers with very different perspectives on how to handle the naughty, are forced to work together to escape their holiday hostage-takers. Alas, the characters we get are The Rock playing a minor variation on the character archetype he’s been grinding into dust for a decade, and Chris Evans as a cynical adult super hacker who needs to learn the true meaning of Christmas. The inclusion of Evans’ character is flimsy and he’s far too annoying to offset whatever advantages he might provide to Santa’s extraction team. The fantasy elements and lore can be fun, like an abominable snowman fight in the tropics, but too many of these elements feel underdeveloped, like the Rock growing big and small for… reasons. Just like how our villain wants to teach the world a lesson in terror… that can be broken by self-reflective apologies. It’s a movie consumed by its many influences. Red One isn’t exactly for little kids, isn’t exactly for adults, and isn’t exactly for teenagers, so who is this for? It’s destined to play in the background and be ignored while holiday naps are had, and to that end, Red One succeeds.

Nate’s Grade: C

You must be logged in to post a comment.