Blog Archives

Opus (2025)

Ever want to watch a second-rate version of The Menu and be left wondering why you didn’t just watch The Menu? That was my main takeaway watching the indie horror/comedy (?) Opus, a darkly satirical look at the music industry and specifically cults of personality. John Malkovich plays Alfred Moretti, an exalted and reclusive musical genius who has earned numerous awards and built a devoted fandom. He’s invited six special guests to a listening party for his new album, the first since his mysterious retirement. It just so happens that party is at his compound and the guests are tended to by a cult of devotees. From there, people start to go missing and weirdness ensues. I was waiting throughout the entirety of Opus for something, anything to really grab me. These are good actors. It’s a premise that has potential. Alas, the movie is uneven and under developed and I found my interest draining the longer it went. The music satire isn’t specific or sharp enough to draw blood or genuine laughs. The weirdness of life on the compound is pretty bland, with the exception of a museum devoted to Moretti’s childhood home that is explored during the climax. The characters are too stock and boring, not really even succeeding as industry send-ups. The music itself is also pretty lackluster, but the movie doesn’t have the courage to argue that the cult has formed around a hack. In the world of Opus, Moretti is an inarguable musical genius. We needed the main character, played by Ayo Edebiri (The Bear), to be an agnostic, someone who doesn’t get the appeal of this musical maven and can destruct his pomposity. Alas, the obvious horror dread of the followers being a murder cult is never given more thought. It’s fine that Opus has familiar horror/cult elements (The Menu, Midsommar, Blink Twice, etc.) but it doesn’t do anything different or interesting with them. It’s obvious and dull without any specific personality to distinguish itself, and if maybe that was the argument against the cult leader, I might see a larger creative design. Instead, it all feels so listless. When the weird cult movie can’t even work up many weird details about its weird cult, then you’re watching a movie that is confused about themes and genre.

Ever want to watch a second-rate version of The Menu and be left wondering why you didn’t just watch The Menu? That was my main takeaway watching the indie horror/comedy (?) Opus, a darkly satirical look at the music industry and specifically cults of personality. John Malkovich plays Alfred Moretti, an exalted and reclusive musical genius who has earned numerous awards and built a devoted fandom. He’s invited six special guests to a listening party for his new album, the first since his mysterious retirement. It just so happens that party is at his compound and the guests are tended to by a cult of devotees. From there, people start to go missing and weirdness ensues. I was waiting throughout the entirety of Opus for something, anything to really grab me. These are good actors. It’s a premise that has potential. Alas, the movie is uneven and under developed and I found my interest draining the longer it went. The music satire isn’t specific or sharp enough to draw blood or genuine laughs. The weirdness of life on the compound is pretty bland, with the exception of a museum devoted to Moretti’s childhood home that is explored during the climax. The characters are too stock and boring, not really even succeeding as industry send-ups. The music itself is also pretty lackluster, but the movie doesn’t have the courage to argue that the cult has formed around a hack. In the world of Opus, Moretti is an inarguable musical genius. We needed the main character, played by Ayo Edebiri (The Bear), to be an agnostic, someone who doesn’t get the appeal of this musical maven and can destruct his pomposity. Alas, the obvious horror dread of the followers being a murder cult is never given more thought. It’s fine that Opus has familiar horror/cult elements (The Menu, Midsommar, Blink Twice, etc.) but it doesn’t do anything different or interesting with them. It’s obvious and dull without any specific personality to distinguish itself, and if maybe that was the argument against the cult leader, I might see a larger creative design. Instead, it all feels so listless. When the weird cult movie can’t even work up many weird details about its weird cult, then you’re watching a movie that is confused about themes and genre.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Mountainhead (2025)

Mountainhead is the first project from writer Jesse Armstrong after the award-winning run of HBO’s Succession. His latest excoriating black comedy takes aim at the tech bro billionaire class and their destructive narcissism during a weekend getaway that descends from petty dick-swinging to plotting a worldwide coup. We’re trapped in this glittering lodge with four selfish billionaires (Steve Carell, Jason Schwartzman, Ramy Youssef, Cory Michael Smith) turning on one another. We’re never meant to empathize with them, only disdain their grievances and slights and unchecked egos and oblivious nature to taking accountability. One of them has released a new generative A.I. that is creating chaos around the globe, with sectarian violence fomenting and the public having a difficult time telling reality from fakery meant to enrage and divide. There’s a lot of phone checking in the movie. Listening to their banter can be like being in a tailspin of self-important CEO tech jargon as they actively dismantle society. The problem is that the movie feels like its stewing in a lower gear for so long, waiting for some escalation or encroaching insight. Then there’s a significant jump for its final act that doesn’t feel set up, and the tone of the movie is too indifferent to expect serious blood by the end. It’s a movie that gets by in its cutting remarks and retorts, but I grew tired of all the peacocking and pomposity of these supposed friends because it felt like the same conversation on repeat without new details or insights. The foursome do well but the real acting standout is Smith (Gotham’s Edward Nygma) as the pathetically vain and insecure Venis. Here is a man you will want to punch in hs smug, grinning face. Mountainhead feels like an under-developed episode for Succession that needed more shaping and direction with its blizzard of down time with bad people.

Mountainhead is the first project from writer Jesse Armstrong after the award-winning run of HBO’s Succession. His latest excoriating black comedy takes aim at the tech bro billionaire class and their destructive narcissism during a weekend getaway that descends from petty dick-swinging to plotting a worldwide coup. We’re trapped in this glittering lodge with four selfish billionaires (Steve Carell, Jason Schwartzman, Ramy Youssef, Cory Michael Smith) turning on one another. We’re never meant to empathize with them, only disdain their grievances and slights and unchecked egos and oblivious nature to taking accountability. One of them has released a new generative A.I. that is creating chaos around the globe, with sectarian violence fomenting and the public having a difficult time telling reality from fakery meant to enrage and divide. There’s a lot of phone checking in the movie. Listening to their banter can be like being in a tailspin of self-important CEO tech jargon as they actively dismantle society. The problem is that the movie feels like its stewing in a lower gear for so long, waiting for some escalation or encroaching insight. Then there’s a significant jump for its final act that doesn’t feel set up, and the tone of the movie is too indifferent to expect serious blood by the end. It’s a movie that gets by in its cutting remarks and retorts, but I grew tired of all the peacocking and pomposity of these supposed friends because it felt like the same conversation on repeat without new details or insights. The foursome do well but the real acting standout is Smith (Gotham’s Edward Nygma) as the pathetically vain and insecure Venis. Here is a man you will want to punch in hs smug, grinning face. Mountainhead feels like an under-developed episode for Succession that needed more shaping and direction with its blizzard of down time with bad people.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Megalopolis (2024)

Trying to make sense of Megalopolis is something of a fool’s errand. It clearly means something significant to its creator, legendary director Francis Ford Coppola. He’s been wanting to make this movie for decades and finally the urge just became too strong to ignore, so he sold his successful Zoetrope winery and put over $100 million of his own fortune into this movie to ensure his vision would be unclouded by meddling studio execs and moneymen. It’s the kind of bracing act of artistic hubris and ambition that is worth celebrating. It’s a big swing from a legendary filmmaker who has quite often gone overboard only to return from the brink with cinematic classics, like Apocalypse Now and Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Given his filmography, you would think that Coppola has more than earned the benefit of the doubt. Except… the Coppola of today isn’t exactly in his prime. He hasn’t had a great movie since 1992’s Dracula, and in those ensuing 30 years, he’s made inexplicable movies like Jack, where Robin Williams plays a kid who ages rapidly, and Twixt, a bizarre misfire with Edgar Allan Poe and vampires that was reportedly inspired by a dream he had. I would expect any new Coppola project to lean more towards these kinds of artistic follies than his generation-defining classics. The man is 85 years old and put all his remaining artistic cache and wealth into guaranteeing that we live in a world with Megalopolis. After seeing his long-gestating opus, I cannot say we are better for the trouble.

It’s hard to condense the plot of Megalopolis because so much is happening while nothing seems that important. For example, brilliant architect Caesar Catilina (Adam Driver) wants to build a new wondrous city he calls Megalopolis, a utopia for the masses. The power brokers of New Rome, including Mayor Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito) and CEO of the largest bank Hamilton Crassu III (Jon Voight), are against such radical changes and see Caesar as an upstart. It also so happens that Caesar can stop time at will, until he cannot. He also has discovered a miracle material to build his futuristic city, but nobody seems to care. The masses of New Rome are more interested in whether or not a pop star is still really a virgin. Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel), the mayor’s party girl daughter, witnesses Caesar stopping time, which is a big deal, or maybe it’s not, but she’s intrigued by the mercurial artist seeking to bring to life his unique vision. But Caesar only likes people interested in art and philosophy and books. Could he fall for her, and will it possibly cost his artistic vision from becoming a shimmering reality of hope?

This is a $100-million-dollar movie created entirely for one person, and if you happen to be Francis Ford Corolla, then congratulations, you will understand and properly appreciate the artistic messages and bravado of Megalopolis. For the rest of us poor souls, we’ll be struggling for meaning and insight. The movie almost exists on a purely allegorical level, or at least it must considering that so much of the scene-to-scene plotting is haphazard and underdeveloped.

Let’s start with the central conflict: why are these forces so immovably against one another? If you were the mayor of a city with a raft of problems, it would sure seem like a great move for a utopian addition. I suppose he and the other men in power are afraid of ceding some of their influence and status to this newcomer, and that is something that could have been explored stronger through generational conflict, the old having a stranglehold on power and losing sight of relevance but still clinging to their storied perches. Caesar should be a threat, an appeal to the people that they no longer truly serve. However, in this story, Caesar is so brilliant and any person standing in his way is meant to look foolish or evil. It reminded me a lot of Ayn Rand’s terrible book Atlas Shrugged that was turned into a terrible trilogy of ideologically rotten movies where the brilliant billionaires are tired of their genius being wasted by government regulation. Obviously Caesar is meant to represent The Artist who is being doubted or interfered with, which is how Coppola views himself, or at least filmmakers in general. Therefore this character can have no flaws and must always be right because the message is to give the great artists their space to be great, to challenge our preconceptions of what art can be. He must be vindicated, so it makes him a rather boring and simplistic character who wants a glorious future for the people.

But what exactly is Megalopolis as a utopia? All we know is that it has moving sidewalks and gyroscope orbs for traveling and it’s very glowy. Visually it reminds me of another Adam Driver movie, 2016’s Midnight Special, when the alien world began co-existing with our world. This magic future city is made of a magic future element that also has the magic ability to heal Caesar after he gets critically injured. All of those details beg for more clarity or development, along with Caesar’s ability to stop time, which I guess is hereditary. These elements should be more impactful, but like the utopian city of Megalopolis, they’re just convenient devices, to simply provide the protagonist with a means of solution whatever his dilemma may be. There’s another conflict in the middle where Caesar is framed with an altered video of him having sex with that virginal pop star, but this too is resolved ludicrously fast. Even this scandal cannot last longer than a few minutes before once again dear Caesar is proven virtuous and unassailable. When he has a magic solution for every problem, including reconstructing a hole in his face, and he can never be wrong, and he has no complexity except for his supposed genius, but his genius is also vaguely defined as far as the actual outcome of his supposed utopia, it makes for an extremely uninteresting main character that gets tiresome as we never flesh out his important attributes.

Likewise, the satire of Megalopolis is fleeting and broad and hard to really engage with. There’s the rich and powerful living in excess and with a sense of depraved callousness toward those they feel are lesser. This is best epitomized by Aubrey Plaza’s tabloid journalist character with the exceptionally bad name of Wow Platinum. She’s a gold digger and flippantly shallow as well as super horny, starting as a fling with Caesar before moving onto Clodio (Shia LeBeouf), the grandson to the CEO of the big bank. This woman has no guile to her and is transparently voracious for all she covets, whether it be sexual or material. With Plaza giving a delightfully campy performance, really digging into the scenery-chewing villainy of her character, it makes her the most entertaining person on screen, and a welcomed respite from all the other actors being so self-serious and stodgy and haughty. This tempers the satiric effect because now I’m looking at Wow Platinum as a godsend. Obviously New Rome is meant to represent the United States, so all of its foreboding narration about the death of empires is meant to make the audience compare the end of Rome to the internal fissures of America. Like everything else in the movie, the comparison is only skin deep, and it’s merely asking you to juxtapose rather than critically compare modern-day to the collapse of Rome. By the end, there’s some definite unsubtle swipes at topical political culture, like when Clodio adopts himself as a humble man of the people to “Make New Rome Great Again” and foments an army of red-hatted rabble. But what exactly is Coppola saying with this? That the people in power will pose as populists to manipulate the lower classes into action that benefits them? Not exactly breaking news, nor is it explored on a deeper or more complex or at least more interesting development. Much like the plotting of Megalopolis, the satirical elements are a cacophonous mess of dispirit ideas and directions.

It’s staggering to believe that the man who wrote Patton and The Godfather is the same man who wrote such lines like, “You’re anal as hell whereas I am oral as hell,” as Plaza looks face-first at Driver’s crotch. The dialogue in this movie is tortured and feels like it was written by A.I., or by aliens who were trying to recreate human social interactions but whose only archive of study was the amazing catalogue of movies by Neil Breen and Tommy Wiseau. The “Entitles me?” conversation that repeats itself four times, the “riches of my Emersonian mind,” to “when we ask questions, that’s basically a utopia,” to what might be the most eye-rolling line of 2024, where a vindictive Voight hides a tiny bow and arrow under a sheet by his waist and literally says, “What do you think of this boner I’ve got here?” Yes, the man who gave us The Godfather has also now given us, “What do you think of this boner I’ve got here?” The movie is so preoccupied with the fall of empires and yet a line of dialogue like that is a sign of the decline of an empire.

Ultimately, Megalopolis reminded me of Richard Kelly’s 2007 flop, Southland Tales, a connection I also felt while watching 2023’s Beau is Afraid as well. I wrote, “It’s because both movies are stuffed to the brim with their director’s assorted odd ideas and concepts, as if either man was afraid they were never going to make another movie again and had to awkwardly squeeze in everything they ever wanted into one overburdened project.” It’s an ungainly mess, a protracted and self-indulgent litany of Coppola’s foibles and follies, and it’s practically impenetrable for an audience. I challenge anyone to seriously engage with this movie beyond rubbernecking. I cannot believe this movie cost $100 million dollars and for a passion project there’s so little that makes me wonder how someone would be so passionate about this. It’s not a good movie but it has its own ongoing fascination for cinephiles morbidly curious what Coppola had to make. These are the kinds of bold artistic swings we should cherish, where filmmakers with storied careers are willing to burn it all down for one more project that must be just so, like Kevin Costner’s four-part Horizon Western that we’ll probably never see completed. I wanted artists to test the waters, to chase their visions, to be ambitious. But that doesn’t mean the art is always worth it.

Nate’s Grade: D

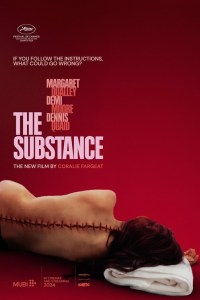

The Substance (2024)

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

Elisabeth (Demi Moore) is a television fitness instructor who has been massively popular for decades. Upon her 50th birthday, she’s promptly dismissed from her job by her studio, concerned over her diminished appeal as a sex symbol. She gets word of a mysterious elixir that can help her reverse the ravages of aging. It arrives via a clandestine P.O. box in a container with syringes and very specific instructions. She needs to spend seven days as her younger self, and seven days as her present self. She needs to “feed” her non-primary self. She also needs to understand that she is still the same person and not to get confused. Elisabeth injects herself with the serum and, through great physical duress, “Sue” emerges from her back like a butterfly sprouting from a fleshy cocoon. As Sue (Margaret Qualley), she’s now able to bask in the fame and attention that had been drifting away. Sue becomes the next hot fitness instructor and everything the studio wants. Except she’s enjoying being Sue so much that going back to her Elisabeth self feels like a punishment. Sue/Elisabeth starts to cheat the very specific rules of substance-dom, and some very horrifying results will transpire as she becomes increasingly desperate to hold onto what she has gained.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

I found the exploration of identity between Sue and Elisabeth to be really interesting, as we’re told repeatedly in the instructions that the two are the same person, and yet the two versions view the other with increasing resentment and hostility. For all intents and purposes, it’s the same woman trying on different outfits of herself, but that doesn’t stop the dissociation. In short order, the two versions view one another as rivals fighting over a shared resource/home. Sue becomes the preferred version and thus the “good times” where she can feel at her best. The older Elisabeth persona then becomes the unwanted half, and the weeks spent outside the coveted persona are akin to a depression. She keeps to herself, gorges on junk food, and anxiously counts the prolonged hours until she can finally transform into Sue. Again, this is the same character, but when she’s wearing the younger woman’s body, it can’t help but trick her into feeling like a different person. This division builds a fascinating antagonism ultimately against herself. She’s literally fighting with herself over her own body, and that sounds like pertinent social commentary to me.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

This is a first-rate body horror parable with wonderfully surreal touches throughout. The creation of Sue, being born from ripping from Elisabeth’s back, is an evocative and shocking image, as is the garish stapling of Elisabeth’s back/entry wound (why it makes for the poster’s key image). It’s reminiscent of a snake slithering out of its old skin, but to also have to take care of that old skin, knowing you have to metaphorically slide it back on, is another matter entirely. The literal dead weight is a reminder of the toll of this process but it’s also like they’ve been given a dependant. The spinal fluid injections are another squirm factor. I loved the way the Kubrickian production design heightens the unreality of the world. I won’t spoil where exactly the movie goes, but know that very bad things will happen beyond your wildest predictions. The finale is a tremendously bonkers climax that fulfills the gonzo, blood-soaked madness of the movie. If you’re a fan of inspired and disturbing body horror, The Substance cannot be missed.

Demi Moore is a fascinating selection for our lead. While it might have been inspired to have Qualley (Maid, Kinds of Kindness) play the younger version of her mother, Andie McDowell (Groundhog Day), it’s meaningful to have Moore as our aging figure of beauty standards. Here is an actress who has often been defined by her body, from the record payday she got for agreeing to bare it all in 1996’s Striptease, to the iconic Vanity Fair magazine cover of her nude and pregnant, to the roles where men are fighting over her body (Indecent Proposal), she’s using her body to tempt (Disclosure), or she’s using her body to push boundaries (G.I. Jane). It’s also meaningful that Moore has been out of the limelight for some time, mimicking the predicament for Elisabeth. Because of her personal history, the character has more meaning projected onto her, and Moore’s performance is that much richer. It reminded me of Nicolas Cage’s performance in Pig, a statement about an artist’s career that has much more resonance because of the years they can parlay into the lived-in role. Moore is fantastic here as our human face to the pressures and psychological torment of aging. She has less and less to hold onto, and in the later stretches of the movie, while Moore is buried under mountains of mutation makeup, she still manages to show the scared person underneath.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Much needs to be said about the hyperbolic sexualization of its characters, particularly Sue as the new young fitness star. Obviously our director is intending to satirize the default male gaze of the industry, as her camera lingers over tawny body parts and close-ups of curves, crevices, and crotches. However, the sexual satire is so ridiculously exploitative that it passes over from being too much and back to the sheer overkill being the point. This is not a movie of subtlety and instead one of intensity to the point that most would turn back and say, “That’s enough now.” For a movie about the perils and pleasures of the flesh, it makes sense for the photography to be as amplified in its rampant sensuality. There are segments where every camera angle feels like a thirsty glamour shot to arouse or arrest, but again this is done for a reason, to showcase Elisabeth/Sue as the world values them. The over-the-top male gaze the movie applies can be overpowering and exhausting, but I think that’s exactly Fargeat’s point: it’s reductive, insulting, and just exhausting to exclusively view women on these narrow terms. This isn’t quite our world, as the number one show on TV is an aerobics instructor, but it’s still close enough. I can understand the tone being too much for many viewers, but if you can push through, you might see things the way Fargeat does, and every lingering and exaggerated beauty shot might make you chuckle. It’s body horror on all fronts, showing the grotesquery not just in how bodies degrade but how we degrade others’ bodies.

On a personal note, while I’ll be back-dating this review, I wrote portions of it while sitting at my father’s bedside during his last days of life. He’s the person that instilled in me the love of movies, and I learned from him the shared language of cinematic storytelling, and one of my regrets is that I didn’t go see more movies with my father while we could. I really wish he could have seen The Substance because he was always hungry for new experiences, to be wowed by something he felt like he hadn’t quite seen before, to be transported to another world. He was also a fan of dark humor, ridiculous plot twists, and over-the-top violence, and I can hear his guffawing in my head now, thinking about him watching The Substance in sustained rapturous entertainment. It’s a movie that evokes strong feelings, chief among them a compulsive need to continue watching. It’s more than a body horror movie but it’s also an excellent body horror movie. Fargeat has established herself, in two movies, as an exciting filmmaker choosing to work within genre storytelling, reusing the tools of others to claim as her own with a proto-feminist spin and an absurdist grin. The Substance is the kind of filmgoing experience so many of us crave: vivid and unforgettable. And, for my money, the grossest image in the whole movie is Dennis Quaid slurping down shrimp.

Nate’s Grade: A

Unfrosted (2024)

What to make of a movie like Netflix’s Unfrosted. It’s Jerry Seinfeld’s directorial debut, working off a screenplay he co-wrote, his first foray into film writing and acting since 2007’s Bee Movie. His eponymous sitcom “about nothing” was a 1990s mainstay and popularized an ironic meta form of comedy that still continues to dominate comedic tastes. Making a movie about the pseudo history of the invention of Pop Tarts, and the corporate rivalry between the major cereal brands, seems like a further exercise in that realm of humor, potentially satirizing a burgeoning sub-genre of late, the Biopic of Products (Air, Tetris, Flamin’ Hot, Blackberry). Except this supposed “biopic about nothing” is really a head-scratcher. Its humor feels pained and stale, the satire feels missing or glancing at best, and it seems like an expensive lark, wasting the nigh-infinite money of Netflix to purposely make a stupid comedy with all his friends.

What to make of a movie like Netflix’s Unfrosted. It’s Jerry Seinfeld’s directorial debut, working off a screenplay he co-wrote, his first foray into film writing and acting since 2007’s Bee Movie. His eponymous sitcom “about nothing” was a 1990s mainstay and popularized an ironic meta form of comedy that still continues to dominate comedic tastes. Making a movie about the pseudo history of the invention of Pop Tarts, and the corporate rivalry between the major cereal brands, seems like a further exercise in that realm of humor, potentially satirizing a burgeoning sub-genre of late, the Biopic of Products (Air, Tetris, Flamin’ Hot, Blackberry). Except this supposed “biopic about nothing” is really a head-scratcher. Its humor feels pained and stale, the satire feels missing or glancing at best, and it seems like an expensive lark, wasting the nigh-infinite money of Netflix to purposely make a stupid comedy with all his friends.

Set in the mid 1960s, we follow two households, both alike in dignity, in fair Battle Creek, Michigan where we lay our scene. Kellogg’s has been the dominant cereal-brand for years but its chief rival, Post, is set to launch a new product that will revolutionize breakfast mornings. Bob (Seinfeld) is the head of development for Kellogg’s and reaches out to his old colleague, Donna (Melissa McCarthy), when it becomes evident that Post stole their unused research to develop a pastry treat designed to be cooked in one’s toaster. The warring CEOs, with Jim Gaffigan as Edsel Kellogg III and Amy Schumer as Marjorie Post, are desperate to one-up one another and be seen as more than an inheritor of their family’s wealth. It’s a race to see which company can get their treat to market first and capture the hearts, minds, and sweet teeth of America’s youth.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t laugh at points through Unfrosted, which operates like a spoof movie on a slower jokes-per-second pacing guide. There are zany sight gags amidst broadly drawn characters treating the silly straight, though occasionally you’ll have wisecrackers commenting on the inherent absurdity of moments, mostly confined to the stars making asides to the audience. Sometimes it’s lazy jokes that rely upon our foreknowledge, like when Bob coins a NASA beverage by saying it has a “real tang” (get it?). The movie frequently intensifies into goofy escalation when Kellogg’s impanels a team of mascots and inventors as a breakfast brain trust. Every one of these wacky characters is here to provide the exact same joke they will provide throughout the movie, and their inclusion is already suspect. Having the Schwinn bicycle guy (Jack McBrayer) comment on why he should be there is not enough. The hit-to-miss ratio will vary per everyone’s personal sense of humor, but overall I just felt mystified why this project would tempt Seinfeld from his comedy repose. What about this idea excited him? Was it just his lifelong love of cereal and Pop Tarts, a topic from his standup act decades ago? I ate a lot of cereal as a teenager too but I don’t want to make a movie about the Lucky Charms advertising campaign teaching children to beat and pillage the Irish (maybe Ken Loach could direct – to the three people on the Internet who appreciate this joke, I want you to know I appreciate you also).

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t laugh at points through Unfrosted, which operates like a spoof movie on a slower jokes-per-second pacing guide. There are zany sight gags amidst broadly drawn characters treating the silly straight, though occasionally you’ll have wisecrackers commenting on the inherent absurdity of moments, mostly confined to the stars making asides to the audience. Sometimes it’s lazy jokes that rely upon our foreknowledge, like when Bob coins a NASA beverage by saying it has a “real tang” (get it?). The movie frequently intensifies into goofy escalation when Kellogg’s impanels a team of mascots and inventors as a breakfast brain trust. Every one of these wacky characters is here to provide the exact same joke they will provide throughout the movie, and their inclusion is already suspect. Having the Schwinn bicycle guy (Jack McBrayer) comment on why he should be there is not enough. The hit-to-miss ratio will vary per everyone’s personal sense of humor, but overall I just felt mystified why this project would tempt Seinfeld from his comedy repose. What about this idea excited him? Was it just his lifelong love of cereal and Pop Tarts, a topic from his standup act decades ago? I ate a lot of cereal as a teenager too but I don’t want to make a movie about the Lucky Charms advertising campaign teaching children to beat and pillage the Irish (maybe Ken Loach could direct – to the three people on the Internet who appreciate this joke, I want you to know I appreciate you also).

It can be fun to simply watch dozens of famous people take their turns being silly in what is unquestionably a “dumb comedy.” When you have comedians of this quality in your movie, they’ll find ways to make even so-so jokes hit a little better, and that’s the case here. There’s an entertainment value in just wondering who will show up next, as many characters are only onscreen for a single scene or an abbreviated moment. Unfrosted becomes an example of Seinfeld’s industry power as he empties his Rolodex to fill even the tiniest of roles. Look, it’s James Marsden as Jack LaLanne. Look, it’s Bill Burr as JFK and Dean Norris as Kruschev (double Breaking Bad). Peter Dinklage as the head of the nefarious milkmen cartel? Why not? If you set your expectations low, maybe lower than what you were accounting for, there can be a mild amusement scene-to-scene just seeing who might show up next, almost like a modern-day version of those anarchic big ensemble comedies like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

There is one segment that fell so flat for me that I was in utter amazement, and that was the unexpected January 6th insurrection parody. In a movie that has sustained a surreal and offbeat version of our universe, it evokes one of the most startling days of recent history. I think the humor is meant to derive from simply seeing a bunch of mascots in big colorful costumes as a mob running havoc, but there’s no jokes about like the challenges of a mascot costume in a fight, or say someone tipping over and being unable to get back up like a helpless turtle. There are jokes that can be had with this scenario, but instead Seinfeld is relying on the ironic juxtaposition of the ridiculous with the serious, and I don’t think it ever works as a joke. My sinking feeling began when Hugh Grant’s embittered mascot character wore a headdress resembling the QAnon shaman. It feels tacky and strange and the longer it persists the more I kept wondering what Seinfeld was doing with this. Why include this especially as the only form of relatively topical political humor, beyond, I guess, the depiction of business elites being complete morons? Why this? Again, it would be different if it was funny in execution, like the Saving Private Ryan D-Day parody from Sausage Party. This just isn’t funny, and its inclusion feels so odd compared to the stale nature of its other comedy.

There is one segment that fell so flat for me that I was in utter amazement, and that was the unexpected January 6th insurrection parody. In a movie that has sustained a surreal and offbeat version of our universe, it evokes one of the most startling days of recent history. I think the humor is meant to derive from simply seeing a bunch of mascots in big colorful costumes as a mob running havoc, but there’s no jokes about like the challenges of a mascot costume in a fight, or say someone tipping over and being unable to get back up like a helpless turtle. There are jokes that can be had with this scenario, but instead Seinfeld is relying on the ironic juxtaposition of the ridiculous with the serious, and I don’t think it ever works as a joke. My sinking feeling began when Hugh Grant’s embittered mascot character wore a headdress resembling the QAnon shaman. It feels tacky and strange and the longer it persists the more I kept wondering what Seinfeld was doing with this. Why include this especially as the only form of relatively topical political humor, beyond, I guess, the depiction of business elites being complete morons? Why this? Again, it would be different if it was funny in execution, like the Saving Private Ryan D-Day parody from Sausage Party. This just isn’t funny, and its inclusion feels so odd compared to the stale nature of its other comedy.

As an admittedly silly enterprise, one that doesn’t even pretend to be accurate even as it flirts with the truth, Unfrosted is a successfully stupid comedy that feels a little too aimless, a little too edge-less and safe, and a little too dated and stale in its approach to comedy (lots of 1960s Boomer nostalgia ahoy). It’s hard to work up that much risible anger over a 90-minute movie that features a living ravioli creature. Clearly this movie wasn’t trying to be anything other than a gleefully stupid comedy, but I wanted more pep from its jokes and whimsy and general idiocy. I think the way to go may have been all the way in the other direction, treating the formation of a toaster pastry like international nuclear secrets and playing the corporate espionage completely straight while also making it patently ridiculous. Unfrosted did, however, make me want a Pop Tart that I ate afterwards, although it was my local grocery store’s generic brand, so I guess that doesn’t directly benefit Kellogg’s. This movie exists as a Seinfeld curiosity that ultimately left me hungry for more.

Nate’s Grade: C

Dream Scenario (2023)

Imagine being the most famous person in the world for doing absolutely nothing, where every person can see you every night, each of them feeling like they own a little piece of you. Now imagine that person being a balding, middle-aged father and professor of evolutionary biology, a man so dull that nobody would likely remember him except that he keeps popping up in everyone’s dreams on a nightly basis. The man in question is Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage), a man so boring that his literal dream is to publish a book on the evolutionary biology of ants. Dream Scenario begins as a sci-fi curiosity and then becomes an intriguing expose on sudden fame as well as the most cogent argument yet on the hazards of a “cancel culture” that too many comedians cling to as an excuse for not being funny. I kept thinking back more and more on the movie, rolling over sequences and choices, as it refused to leave my waking thoughts.

Imagine being the most famous person in the world for doing absolutely nothing, where every person can see you every night, each of them feeling like they own a little piece of you. Now imagine that person being a balding, middle-aged father and professor of evolutionary biology, a man so dull that nobody would likely remember him except that he keeps popping up in everyone’s dreams on a nightly basis. The man in question is Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage), a man so boring that his literal dream is to publish a book on the evolutionary biology of ants. Dream Scenario begins as a sci-fi curiosity and then becomes an intriguing expose on sudden fame as well as the most cogent argument yet on the hazards of a “cancel culture” that too many comedians cling to as an excuse for not being funny. I kept thinking back more and more on the movie, rolling over sequences and choices, as it refused to leave my waking thoughts.

There’s an obvious and easy parallel between what Paul is experiencing and general celebrity, where members of the public have an individual relationship to a person but divorced from the reality of who that person may or may not be, as well as one-sided. These are strangers to Paul but so many feel like they know him, like a neighbor, or a lover, or a threat to someone’s mental stability. It’s an ongoing struggle of rationalizing different perceptions of a person, where so many project what they want onto this smiling bald man who has become a national figure of fascination. Given the premise, I completely understand. I can only fleetingly remember my own dreams maybe once every two weeks, but if a real person, who I’ve never met, continued to make strange cameo appearances, I would definitely investigate further. That’s a genuine mystery that could break through even our jaded media culture. The big question would be why is this happening but the more interesting question is why this guy? What makes him special? I was always engaged with the movie and impressed by the turns the screenplay made, providing insightful glimpses into human nature that felt relatable as well as realistic in response to this phenomenon. Of course there are certain people that view him as some angel, whereas others a devil needing to be stopped, and some an unknown being they’ve projected sexual feelings onto. There’s a very funny and also deeply uncomfortable sequence where a young woman tries to recreate her erotic dream with the real Paul, and of course the real Paul fails to measure up to the fantasy mystique. I was also intrigued by the question of why Paul does not appear in his wife’s dreams. The screenplay by director Kristoffer Borgli is consistently well-developed and full of changes and challenges that had me glued, though I should warn you, dear reader, that you will never be given a concrete reason why the dreams began.

The first half of the movie is Paul’s ascension, enjoying his notoriety and the new access he has to getting published and achieving his dreams that felt stalled for too long. It’s the positivity of the fame and untapped desire of the general public, with the assorted weirdo from time to time. Then there is a significant turn, and the movie gives a clear theory as to why, and the dreams all of a sudden now become nightmares. Instead of Paul just being in the background of everyone’s dreams, acting as an observer rarely doing much of anything, now he’s become a malevolent force, a stalker, a killer, or worse. Now the general public fears this man and fears going to sleep with the certainty that Paul will be waiting for them to perform any manner of terrors. Paul is placed on sabbatical after his very presence on campus drives students away into hyperventilating. Paul is genuinely pained by this but also painfully annoyed, as he argues he cannot be responsible for the dreams of others and what happens inside every individual subconscious. He hasn’t really done anything in physical reality, and yet he’s kicked out of restaurants, shunned by his colleagues, and his endorsement deals are drying up with the exception of the alt-right.

The first half of the movie is Paul’s ascension, enjoying his notoriety and the new access he has to getting published and achieving his dreams that felt stalled for too long. It’s the positivity of the fame and untapped desire of the general public, with the assorted weirdo from time to time. Then there is a significant turn, and the movie gives a clear theory as to why, and the dreams all of a sudden now become nightmares. Instead of Paul just being in the background of everyone’s dreams, acting as an observer rarely doing much of anything, now he’s become a malevolent force, a stalker, a killer, or worse. Now the general public fears this man and fears going to sleep with the certainty that Paul will be waiting for them to perform any manner of terrors. Paul is placed on sabbatical after his very presence on campus drives students away into hyperventilating. Paul is genuinely pained by this but also painfully annoyed, as he argues he cannot be responsible for the dreams of others and what happens inside every individual subconscious. He hasn’t really done anything in physical reality, and yet he’s kicked out of restaurants, shunned by his colleagues, and his endorsement deals are drying up with the exception of the alt-right.

The premise also allows for plenty of beguiling and funny and creative imagery. Since we’re dealing with a wealth of dreams, this allows the filmmakers a near limitless opportunity to hit whatever themes or oddities they desire under the pretense of retelling a dream. We get the mundane, we get the horrifying, which plays out with some effective jump scares, and we get plenty of surreal moments. This artistic choice allows for an ending that feels ambiguously bittersweet but also tragically fitting and satisfying. It felt exactly how it should have been. It reminded me of Being John Malkovich, and truthfully this movie feels like a lost Charlie Kaufman story. The consumerism satire is also right on target, from Paul’s initial agency meeting trying to get him to endorse Sprite in the dreams of millions, to the application of harnessing people’s dreams to sell products or further one’s social media branding. It feels topical while also a sadly logical extension.

For me, this is the most interesting satirical broadside yet exploring the concept of “cancel culture,” a term often so overblown to the point of being a nonsensical catch-all for consequences. Paul’s sense of grievance is real, but the movie doesn’t present him as a martyr and instead chooses to use this transition, from curiosity to pariah and national nightmare, to better satirize people’s attempts to manipulate their own flailing narratives (see: ukulele apology videos, self-imposed exile for “listening,” late-night Ambien usage, etc.). After Paul has a nightmare of his own, starring himself, he records a manic tear-filled self-pittying apology to appeal to his detractors saying he now too has those “lived experiences” with transparent insincerity, and of course it doesn’t appeal to anyone and he’s even more ridiculed and despised. I enjoy that the movie doesn’t want to dwell in the tragedy or general unfairness of this turn of events with Paul becoming the world’s most hated man. Paul also refuses to accommodate or acknowledge other people’s discomfort, overriding security concerns and repeatedly placing his family and children in uncomfortable if not humiliating positions because dear old dad just refuses to accept mollifying his behavior for their social benefit. Paul was riding high on the ego trips of the unexpected attention and adoration, and occasional starry-eyed groupie, and he’s fighting to regain that same level of credibility and status before he retreats back to being a punchline, an asterisk in history, a trivia answer on a game card.

Dream Scenario tackles the rise-and-fall of overnight celebrity and sudden fame and adds an intriguing sci-fi spin as well as some arty yet accessible meditation and fun satirical social commentary. It asks us to contemplate the nature of our dreams and how we might behave under this extraordinary scenario, whether as one of the people befuddled by the dreams or the even larger befuddlement of the person appearing in all those millions of dreams. It asks us to reconsider perception, as well as how well others may know us, as well as what we look for with our own dreams. When Paul’s wife (Julianne Nicholson) admits her own fantasy and it involves him wearing an old 80s costume that she found to be surprisingly sexy, he’s a little let down that this is all she has for her dreams, and that to me seems like a fine central theme to ground this movie. It’s easy to go crazy with limitless possibilities, but we often return to what matters most, and that’s often idiosyncratic, personal, and perhaps underwhelming to an outsider who lacks the context and, sorry, lived experiences. Our dreams can help define us but not necessarily as extravagant escapism. It can also be the ordinary, the unusual, the moments and people we just want to revisit a little longer. Now imagine this hijacked, weaponized, and then hacked into ad space, and you have Dream Scenario, a peculiar yet arresting little movie that has lots of intriguing ideas to share.

Dream Scenario tackles the rise-and-fall of overnight celebrity and sudden fame and adds an intriguing sci-fi spin as well as some arty yet accessible meditation and fun satirical social commentary. It asks us to contemplate the nature of our dreams and how we might behave under this extraordinary scenario, whether as one of the people befuddled by the dreams or the even larger befuddlement of the person appearing in all those millions of dreams. It asks us to reconsider perception, as well as how well others may know us, as well as what we look for with our own dreams. When Paul’s wife (Julianne Nicholson) admits her own fantasy and it involves him wearing an old 80s costume that she found to be surprisingly sexy, he’s a little let down that this is all she has for her dreams, and that to me seems like a fine central theme to ground this movie. It’s easy to go crazy with limitless possibilities, but we often return to what matters most, and that’s often idiosyncratic, personal, and perhaps underwhelming to an outsider who lacks the context and, sorry, lived experiences. Our dreams can help define us but not necessarily as extravagant escapism. It can also be the ordinary, the unusual, the moments and people we just want to revisit a little longer. Now imagine this hijacked, weaponized, and then hacked into ad space, and you have Dream Scenario, a peculiar yet arresting little movie that has lots of intriguing ideas to share.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Fool’s Paradise (2023)

Charlie Day is a very funny guy who works with lots of funny people, so why isn’t his directorial debut, Fool’s Paradise, well, funnier? It’s about a mute simpleton (Day) with the intelligence of a five-year-old, or a Labrador retriever we’re told, who is mistaken for an acting savant. The intended joke is that this industry projects what it wants to see and is full of shallow, insecure, greedy idiots chasing anything that might be popular or career advancing. That’s a fine start but there is a shocking lack of jokes and funny scenarios to be had here, so the 93 minutes just creaks on by in protracted and pained awkward silence. It was a mistake to have Day, a comedian with such a distinct voice and often prone to hilarious outbursts, play a character who doesn’t talk at all. It’s not just that, he kind of shrugs or raises his eyebrows in response, and every time the camera cuts to him for a reaction shot, I was left wondering if this is all the movie had. This passive character, mistakenly named “Latte Pronto” by a director who finds him as a replacement for a prima donna Method actor (also Day), is just a miss. He’s not interesting, and what her reveals about the people around him is even less interesting and just as obvious and tiresome. It’s a movie about non-stop mugging to the camera and hoping to evoke some overly generous pity laughs. It’s attitude over wit. The jaunty score tries hard to make you feel the missing levity from scene to scene. It’s not convincing. The movie is chock full of stars, many of them friends and colleagues that Day has accumulated over a decade in comedy, but nobody has anything funny to do. It’s just all so confounding. Clearly the inspiration owes a debt to 1979’s Being There, a gentle political and social satire where everyone projects what they want to see on one middle-aged gardener raised on TV (I recently watched that movie and felt it was rather dated and quaint). At least that movie had a larger point. There’s just so little to hold onto with Fool’s Paradise, with a boring nothing of a character that never seems to uncover or reveal anything on a tour through Day’s many famous friends. Even the physical comedy is an afterthought. This is no charming Little Tramp. Do yourself a favor and watch any 90 minutes of 2022’s Babylon and you’ll see a funnier and more excoriating satire on Hollywood than the collective shrug that is Fool’s Paradise.

Charlie Day is a very funny guy who works with lots of funny people, so why isn’t his directorial debut, Fool’s Paradise, well, funnier? It’s about a mute simpleton (Day) with the intelligence of a five-year-old, or a Labrador retriever we’re told, who is mistaken for an acting savant. The intended joke is that this industry projects what it wants to see and is full of shallow, insecure, greedy idiots chasing anything that might be popular or career advancing. That’s a fine start but there is a shocking lack of jokes and funny scenarios to be had here, so the 93 minutes just creaks on by in protracted and pained awkward silence. It was a mistake to have Day, a comedian with such a distinct voice and often prone to hilarious outbursts, play a character who doesn’t talk at all. It’s not just that, he kind of shrugs or raises his eyebrows in response, and every time the camera cuts to him for a reaction shot, I was left wondering if this is all the movie had. This passive character, mistakenly named “Latte Pronto” by a director who finds him as a replacement for a prima donna Method actor (also Day), is just a miss. He’s not interesting, and what her reveals about the people around him is even less interesting and just as obvious and tiresome. It’s a movie about non-stop mugging to the camera and hoping to evoke some overly generous pity laughs. It’s attitude over wit. The jaunty score tries hard to make you feel the missing levity from scene to scene. It’s not convincing. The movie is chock full of stars, many of them friends and colleagues that Day has accumulated over a decade in comedy, but nobody has anything funny to do. It’s just all so confounding. Clearly the inspiration owes a debt to 1979’s Being There, a gentle political and social satire where everyone projects what they want to see on one middle-aged gardener raised on TV (I recently watched that movie and felt it was rather dated and quaint). At least that movie had a larger point. There’s just so little to hold onto with Fool’s Paradise, with a boring nothing of a character that never seems to uncover or reveal anything on a tour through Day’s many famous friends. Even the physical comedy is an afterthought. This is no charming Little Tramp. Do yourself a favor and watch any 90 minutes of 2022’s Babylon and you’ll see a funnier and more excoriating satire on Hollywood than the collective shrug that is Fool’s Paradise.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Barbie (2023)

Who would have guessed a movie based upon a ubiquitous doll that dates back to the 1950s would become not just a cultural force and reclamation project but also the biggest moviegoing event of the year, as well as the highest-grossing movie in Warner Brothers’ history, even outpacing The Boy Who Lived? In 2023, it turns out we are all, every one, a Barbie girl living in a Barbie world. I came to this experience late, wondering if writer/director Greta Gerwig’s movie could live up to the lavish hype, the fawning praise, the hilarious offenses that many fragile males have levied against it. It couldn’t possibly be that good, could it? I saw it with three generations of women in my family, something I will privilege, and I must say, it is that good. Barbie is one of the best movies of the year and a shining example of what vision and passion can do to elevate any story. There’s so many ways this movie could have just been cheap corporate slop and instead it becomes an existential yet deeply personal treatise on life and death.

In the world of Barbies, women rule and the men are just afterthoughts. In this creation myth, the Kens were meant to compliment the Barbies. We watch “Stereotypical Barbie” (Margot Robbie) go through her daily routine of fun, frivolity, and nightly dance parties with all her best gal pals (no boys, er Kens, allowed). Then one day, this blonde Barbie started walking differently, started seeing the world differently, and started wondering about dying. Was there something wrong? Her human owner, in the real world, was in trouble, so Barbie sets off on an adventure to find her human owner and save the day, with help from her boyfriend, Ken (Ryan Gosling). Except for these two, the real world is very different from what they were expecting.

It’s easy to see how this movie could have been a mediocre fish-out-of-water comedy, with Barbie clashing in our modern-day world with its modern-day views of fashion, body image, and what skinny, buxom dolls represent to generations of young impressionable children. It’s clear to see what the scrapped version could have been when Amy Schumer was attached to star. What really impressed me with Barbie, beyond its delightful and inspired production values, is how ambitious and well-realized this movie is at every turn. It could have settled for easy jokes about Barbie and Ken not fitting in, not understanding human relationships and sex, and that stuff is there and it’s quite funny, but Gerwig and co-writer Noah Baumbach want to do so much more. This is a studio blockbuster, based upon a decades-long popular toy, that wants to do more with its platform. It aims higher, and in just about every measure, Barbie admirably succeeds. As a comedy, it had me howling with laughter, enough so that my response was providing another level of entertainment for my wife. There are jokes that are so specific, so beautifully targeted, that when they detonated, I was in awe and appreciation, (a reference to the literal definition of fascism and a Snyder Cut throwaway reference were perfectly attuned to my comedy sensibilities, thank you, Greta). As a frothy and fun fantasy, the movie has excellently crafted sets and costumes and retro visual aesthetics, making the movie a pink-accentuated sensory bombardment. But as a satire is where Barbie really becomes special.

Again, it would be easy for Barbie to learn lessons about body diversity and positivity and likely be browbeaten into what a good feminist is supposed to be, that the real world is a harder place for women than she previously thought. All of that is there, along with a consistent and entertaining critique of the faults of patriarchal society, but Barbie isn’t some reductive, man-hating screed to indoctrinate women into thinking they don’t need men (men are already very good at convincing women they don’t need men). This is a treatise on the power of inclusion and how this benefits society, both for men and for women. In Barbie Land, it’s a matriarchal society where girls rule and boys drool, but it’s a fantasy world reminiscent of a caste system, where the Kens will always be lesser afterthoughts because, well, they’re not Barbies, they’re just Kens. They are excluded in their own world. That’s why Gosling’s Ken is so excited by the real world, where the status quo is flipped, where the world is run by men, as he now sees this as an opportunity that has been denied to him. He wants to recreate his own version of the patriarchy not because he thinks women are inferior but because he just wants to be in power and respected, so he’s replicating his misguided understanding of what men in power are like, which naturally involves lots of horses. In the real world, Ken admonishes a suit-wearing corporate executive that they aren’t doing patriarchy right, to which the man winks and says, “We’re just better about hiding it.” The final act isn’t about “bringing down the patriarchy,” it’s about making a more inclusive world where people don’t have to feel marginalized and stuck and resentful.

Besides its social satire, there are other areas where Barbie goes deeper in surprising and affecting ways. There are more than a few applause-worthy moments explaining the perspective of women, particularly a monologue that is destined to be an audition piece for the rest of time, and it all works and is cutting without being too didactic. Gerwig even gets in a few jabs about corporate culture (“Are there any actual women in this boardroom?” “I’m a man with no power, does that make me a woman?”) and Mattel as an organization becomes another force of antagonism spearheaded by hapless buffoonish men (of course you get Will Ferrell to play the Mattel CEO). The biggest surprise is how emotional and deep the movie can become. There will be plenty that tear up just having a big Hollywood movie recognize their day-to-day emotional toil of being a woman in modern society. For me, the questions over what to do with the life we have flirted with some surprising existential contemplation, as Barbie is reminded at several points that death is a reality and yet would she want to move to the human world? An emotional highlight occurs when Stereotypical Barbie is speaking with the equivalent of her creator, and Billie Eilish’s tender-to-the-point-of-breaking song “What Was I Made For” lilts onto the soundtrack, and the sincerity of this sequence, topped with insert home video footage from the production cast and crew, really hit home how much more this movie is going for then bringing different dolls to life. It’s not just jokes about crotch-less creatures and weird feet, it’s about how we can live and why we do so, what inspires us. It’s a big studio summer release that flirts with the profundity and brevity of life.

There is one actor who deserves their own special recognition and that is Gosling (The Nice Guys), who so rarely gets to showcase his sharp comedy skills with the dour, serious, insular roles he gravitates to. Gosling is so committed to his role that he is operating on another plane of excellence, hitting sly jokes within jokes and selling every wonderfully stupid moment with Ken. This man isn’t afraid to look silly, he fully courts it, embraces it at every opportunity, and yet his performance doesn’t detract from Robbie but only makes them both shine brighter. He reminded me of Tommy Wiseau at points. His hilarious ballad “I’m Just Ken,” which segues into a wild West Side Story-style dance battle that is peak peacocking, is a phenomenal run of inspired silliness (the storming of the Malibu beach had me rolling), yet also connected to the character’s co-dependent arc and dissatisfaction with himself (when feeling down, just quote: “I’m just Ken, and I’m enough, and I’m great at doing stuff”). Ken has to learn to think of himself outside his combined definition with Barbie, and they both need to spend time discovering who they really are rather than who they think they’re supposed to be before considering forming attachments. I would not be surprised if Gosling earns a Best Supporting Actor nomination. It was the role he was born to play: insecure accessory doofus.

Gerwig has launched to mega-stardom with just three directing efforts (four if you count her co-directing effort in 2008 with Nights and Weekends, back in her early mumblecore breakout days). Already this woman has been nominated for Best Director, one of only seven ever, and she now owns the highest grossing movie of the year as well as in studio history. She’s proven herself with her 2017 coming-of-age semi-autobiographical Lady Bird, richly realized and achingly felt, with an established literary classic that is a foundation to generations, and had been adapted a dozen ways for the cinema, and yet she found ways to make her 2019 Little Women modern and personal, and now, on her biggest stage, being handled corporate IP that would be perfectly fine with just selling more toys, she has made a movie for the moment, something that compelled audiences back to theaters in droves, that will become a staple for a generation of film lovers. With just three movies, Gerwig has established herself in a league of her own as a director. Anyone who can turn the Barbie movie into a hilarious, poignant, and meaningful meditation on our times, on the relationships between mothers and daughters, and on life itself is a talent that deserves every creative latitude to achieve her vision. The voice and vision behind this, even to the smallest detail, is so impressive and fully committed and well developed and fabulous. Barbie is one of the best movies of the year and proof that studio blockbusters can indeed be more.

Nate’s Grade: A

Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022)

Bodies Bodies Bodies is a darkly comic horror indie but the most horrifying aspect is being trapped in a house with these obnoxious Gen Z stereotypes. A gathering of drug-addled teenagers is interrupted by two major events: a hurricane isolating everyone inside the posh Floridian estate, and a hidden murderer among their ranks picking them off. The problem with this would-be Scream scenario is that its screenplay is hampered by tonal anguish; it’s not scary enough to unsettle, and it’s certainly not funny or satirically lancing enough to count. These cringe-worthy caricatures of Gen Z as over-stimulated, over-entitled, and over-offended are hacky and feel like somebody collected a lazy grab bag of generational complaints. Everyone in this movie is annoying or unlikeable or shallow or selfish or plainly insufferable. I know the movie wants to satirize the worst of modern social media-heavy teen friendships, but it feels written by someone who hates Gen Z but without deeper understanding of the foibles of Gen Z struggles. Cultural buzzwords will be thrown out (podcasts, ablest, gaslighting, feelings are facts, appropriation, triggering, etc.) with abandon but it all feels so phony and dubious. The central mystery has some appeal, and there are some performers who make the most of their sketchy characters, like Shiva Baby‘s Rachel Sennet and a well-cast Pete Davidson, but more often the actors are trapped from such limited material, especially Oscar-nominee Maria Bakalova (Borat 2) as our sheltered protagonist navigating this weird world of privilege. The horror elements feel entirely out of balance, utilizing the dark environment and rave glow band-lighting accents for most of its lackluster, murky atmosphere. Bodies Bodies Bodies has some shining moments but far too much down time with inauthentic yet very insufferable characters, and after 80 minutes, I didn’t care who survived because my patience had long been murdered.

Bodies Bodies Bodies is a darkly comic horror indie but the most horrifying aspect is being trapped in a house with these obnoxious Gen Z stereotypes. A gathering of drug-addled teenagers is interrupted by two major events: a hurricane isolating everyone inside the posh Floridian estate, and a hidden murderer among their ranks picking them off. The problem with this would-be Scream scenario is that its screenplay is hampered by tonal anguish; it’s not scary enough to unsettle, and it’s certainly not funny or satirically lancing enough to count. These cringe-worthy caricatures of Gen Z as over-stimulated, over-entitled, and over-offended are hacky and feel like somebody collected a lazy grab bag of generational complaints. Everyone in this movie is annoying or unlikeable or shallow or selfish or plainly insufferable. I know the movie wants to satirize the worst of modern social media-heavy teen friendships, but it feels written by someone who hates Gen Z but without deeper understanding of the foibles of Gen Z struggles. Cultural buzzwords will be thrown out (podcasts, ablest, gaslighting, feelings are facts, appropriation, triggering, etc.) with abandon but it all feels so phony and dubious. The central mystery has some appeal, and there are some performers who make the most of their sketchy characters, like Shiva Baby‘s Rachel Sennet and a well-cast Pete Davidson, but more often the actors are trapped from such limited material, especially Oscar-nominee Maria Bakalova (Borat 2) as our sheltered protagonist navigating this weird world of privilege. The horror elements feel entirely out of balance, utilizing the dark environment and rave glow band-lighting accents for most of its lackluster, murky atmosphere. Bodies Bodies Bodies has some shining moments but far too much down time with inauthentic yet very insufferable characters, and after 80 minutes, I didn’t care who survived because my patience had long been murdered.

Nate’s Grade: C

You must be logged in to post a comment.