Blog Archives

Wolf Man (2025)

I had high hopes for writer/director Leigh Whannell’s second take on the classic monsters after how thrilling and satisfying his take on the Invisible Man was in the early months of 2020. Werewolves have served as a fertile metaphorical ground for genre storytelling to cover such varied topics like coming of age, self-actualization, and addiction. Considering Whannell was able to use an invisible man to explore toxic masculinity and gaslighting, without losing sight of a monstrously entertaining movie, I was hoping for repeated success. Wolf Man is ostensibly about inherited curses and the relationships between fathers and children, but it’s really about dealing with flaring tempers and whether or not our shortcomings are a result of our genetic inheritance. It’s also about a family trapped in a cabin helplessly watching their father/husband transform into a dangerous beast. I suppose there’s something here about the cycles of trauma and abuse, anger as a sickness, but the problem with Whannell’s Wolf Man is that it all feels like an incomplete beginning. There are definite identifiable themes here, and a scenario that would lend to slow-building dread amid losing control over one’s sanity to become a monster against their loved ones. I just kept waiting for something more. The movie runs out of steam shockingly once it strands its family in the cabin. We’re treated to many scenes of Christopher Abbott, as the beleaguered father, blankly staring and then seeing his vision where people are highlighted with neon outlines. It’s a neat visual but what does it mean? I was waiting for more development, more character work, more culminating of themes, more… anything. It’s a lot of sitting around, like this promising genre movie had been hijacked by, like, some self-sabotaging arty Godard-obsessed filmmaker trying to Say Something with all the protracted scenes, pained silences, and repetition without revelation. It’s a surprisingly boring movie and, I repeat, it’s a werewolf movie. The makeup effects also make our titular monster look more like a shaved wolf, or a goblin rather than a lupine-centric creature of the night. I don’t even think there was a single shot of a full moon in the whole movie. Regardless, Wolf Man is a disappointing a d dull monster movie that’s too shaggy for its own good.

I had high hopes for writer/director Leigh Whannell’s second take on the classic monsters after how thrilling and satisfying his take on the Invisible Man was in the early months of 2020. Werewolves have served as a fertile metaphorical ground for genre storytelling to cover such varied topics like coming of age, self-actualization, and addiction. Considering Whannell was able to use an invisible man to explore toxic masculinity and gaslighting, without losing sight of a monstrously entertaining movie, I was hoping for repeated success. Wolf Man is ostensibly about inherited curses and the relationships between fathers and children, but it’s really about dealing with flaring tempers and whether or not our shortcomings are a result of our genetic inheritance. It’s also about a family trapped in a cabin helplessly watching their father/husband transform into a dangerous beast. I suppose there’s something here about the cycles of trauma and abuse, anger as a sickness, but the problem with Whannell’s Wolf Man is that it all feels like an incomplete beginning. There are definite identifiable themes here, and a scenario that would lend to slow-building dread amid losing control over one’s sanity to become a monster against their loved ones. I just kept waiting for something more. The movie runs out of steam shockingly once it strands its family in the cabin. We’re treated to many scenes of Christopher Abbott, as the beleaguered father, blankly staring and then seeing his vision where people are highlighted with neon outlines. It’s a neat visual but what does it mean? I was waiting for more development, more character work, more culminating of themes, more… anything. It’s a lot of sitting around, like this promising genre movie had been hijacked by, like, some self-sabotaging arty Godard-obsessed filmmaker trying to Say Something with all the protracted scenes, pained silences, and repetition without revelation. It’s a surprisingly boring movie and, I repeat, it’s a werewolf movie. The makeup effects also make our titular monster look more like a shaved wolf, or a goblin rather than a lupine-centric creature of the night. I don’t even think there was a single shot of a full moon in the whole movie. Regardless, Wolf Man is a disappointing a d dull monster movie that’s too shaggy for its own good.

Nate’s Grade: C

The Monkey (2025)

It was only minutes when I thought to myself, “I think I love this movie.” To be fair, this movie might only jibe for a very select few with a penchant for gory, outlandish horror and a demented sense of humor, but it just so happens that specific population includes yours truly. The Monkey is a dark comedy about the cruel indifference of fate disguised as a supernatural thriller adaptation of a Stephen King short story. It’s about two twin brothers (both played by Theo James as an adult) coming to terms with a family curse, a toy monkey that, when wound up, will beat its drum until the final blow correlates with the sudden, often shocking death of a random person. It’s essentially a death device and the brothers are haunted by it since losing both of their parents to it as teenagers, both grasping for meaning from their tragedy. One of them blames himself and the other blames his brother, and this has warped them into adulthood and how they view themselves, their responsibility as a parent, and their hostility to one another. The movie becomes a cagey reunion between the two brothers while also vying for power over a dangerous totem that loves elaborate Final Destination-style calamities. These deaths are over-the-top, often with bodies exploding in bloody heaps, and I found myself cackling along in response to the ridiculous violence. This is quite a change of pace for writer/director Osgood Perkins who just last year helmed the Satanic serial killer thriller Longlegs. Whereas that movie was a bit too lost in its slow-build atmosphere and a jumbled story burdened with underdeveloped plot elements, The Monkey is refreshingly straightforward and always entertaining in its contained madness. There are some bold and dark choices made and I appreciated every one of them. This is really a movie about trying to make sense of death and grief but it’s through the visage of spilled viscera and gallows humor. I didn’t think I’d walk away saying this, but I can’t wait to show my wife the movie about the killer windup monkey.

It was only minutes when I thought to myself, “I think I love this movie.” To be fair, this movie might only jibe for a very select few with a penchant for gory, outlandish horror and a demented sense of humor, but it just so happens that specific population includes yours truly. The Monkey is a dark comedy about the cruel indifference of fate disguised as a supernatural thriller adaptation of a Stephen King short story. It’s about two twin brothers (both played by Theo James as an adult) coming to terms with a family curse, a toy monkey that, when wound up, will beat its drum until the final blow correlates with the sudden, often shocking death of a random person. It’s essentially a death device and the brothers are haunted by it since losing both of their parents to it as teenagers, both grasping for meaning from their tragedy. One of them blames himself and the other blames his brother, and this has warped them into adulthood and how they view themselves, their responsibility as a parent, and their hostility to one another. The movie becomes a cagey reunion between the two brothers while also vying for power over a dangerous totem that loves elaborate Final Destination-style calamities. These deaths are over-the-top, often with bodies exploding in bloody heaps, and I found myself cackling along in response to the ridiculous violence. This is quite a change of pace for writer/director Osgood Perkins who just last year helmed the Satanic serial killer thriller Longlegs. Whereas that movie was a bit too lost in its slow-build atmosphere and a jumbled story burdened with underdeveloped plot elements, The Monkey is refreshingly straightforward and always entertaining in its contained madness. There are some bold and dark choices made and I appreciated every one of them. This is really a movie about trying to make sense of death and grief but it’s through the visage of spilled viscera and gallows humor. I didn’t think I’d walk away saying this, but I can’t wait to show my wife the movie about the killer windup monkey.

Nate’s Grade: A-

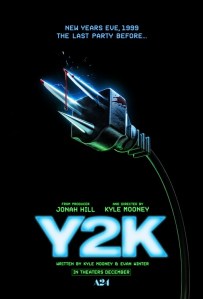

Y2K (2024)

The premise for Y2K is ripe for fun. It’s a nostalgic retelling of that turn-of-the-millenium anxiety over computers getting confused, and the movie says what if technology had turned on humans at the stroke of midnight that fateful New Year? Add the lo-fi chintzy, quirky style of co-writer/director Kyle Mooney (Brigsby Bear) and it’s a setup for some strange and amusing techno-horror. It’s structured like a teen party movie with our group of high schoolers (Jaeden Martell, Julien Dennison, Rachel Zegler) trying to step out of their comfort zones and live their best lives… around machines trying to eviscerate them. The tonally messy movie lacks the heart and specific world-building weirdness of Brigsby Bear, instead relying upon the genre cliches of the high school movie, including the unrequited nerd crush and the pretty popular girl who’s more than what she seems. While watching Y2K, I kept getting the nagging feeling that this movie should be more: more funny, more imaginative, more weird. It’s quite uneven and veers wildly from set piece to set piece for fleeting entertainment. I chuckled occasionally but that was it. I enjoyed the villainous robot assembling itself with assorted junk available, and it’s hard not to see this as a general statement about the movie as a whole. It’s a bit lumbering, a bit underdeveloped, a bit formless, blindly swiping nostalgia and junk to build some form of an identity that never materializes beyond its parts. Y2K won’t make me bail on Mooney as a filmmaker but it’s a party worth missing.

Nate’s Grade: C

Blink Twice (2024)

Zoe Kravitz’s directorial debut Blink Twice has stayed with me for weeks after I watched it, and with further harrowing revelations coming from the fallout of P. Diddy’s empire of exploitation, it has even more relevance. Think of it as a feminist revenge thriller set on Jeffrey Epstein’s island or a Diddy party. Channing Tatum plays a successful tech bro who hosts lavish getaways for the Wall Street and Silicon Valley elite, where the week is an orgy of food, drink, drugs, and of course sex. We follow Frida (Naomi Ackie), a waitress yearning for the finer things in life, so when Tatum’s rich and famous CEO invites her and her friend to his private island, she’s ecstatic. But everything is not what it seems, and Frida and the other women begin to notice weird clues, that is, when they can remember as time frequently seems to be lost for them. Blink Twice is a twisty, eerie mystery and Kravitz shows real skill at developing tension and suspense, with sequences that had me girding great waves of anxiety. There’s also an eye for style and mood here that makes me feel Kravitz has a real career as a genre director. I don’t think it’s spoilers to say that eventually the surviving women team up together to fight back against their oppressors, and it’s gloriously entertaining, bloody, and table-turning satisfying. The ending is designed to spark debate and controversy, and I enjoy that Kravitz and co-writer E.T. Feigenbaum do not want to make things too tidy, even with their protagonists. The themes here are broad but the execution is exact. There are several moments that stand out to me, from unexpected moments of levity to bold artistic choices that are mesmerizing, like an “I’m sorry” apology that goes through every level. If you’re looking for slickly executed genre thrills with great comeuppance, don’t blink when it comes to with Blink Twice.

Zoe Kravitz’s directorial debut Blink Twice has stayed with me for weeks after I watched it, and with further harrowing revelations coming from the fallout of P. Diddy’s empire of exploitation, it has even more relevance. Think of it as a feminist revenge thriller set on Jeffrey Epstein’s island or a Diddy party. Channing Tatum plays a successful tech bro who hosts lavish getaways for the Wall Street and Silicon Valley elite, where the week is an orgy of food, drink, drugs, and of course sex. We follow Frida (Naomi Ackie), a waitress yearning for the finer things in life, so when Tatum’s rich and famous CEO invites her and her friend to his private island, she’s ecstatic. But everything is not what it seems, and Frida and the other women begin to notice weird clues, that is, when they can remember as time frequently seems to be lost for them. Blink Twice is a twisty, eerie mystery and Kravitz shows real skill at developing tension and suspense, with sequences that had me girding great waves of anxiety. There’s also an eye for style and mood here that makes me feel Kravitz has a real career as a genre director. I don’t think it’s spoilers to say that eventually the surviving women team up together to fight back against their oppressors, and it’s gloriously entertaining, bloody, and table-turning satisfying. The ending is designed to spark debate and controversy, and I enjoy that Kravitz and co-writer E.T. Feigenbaum do not want to make things too tidy, even with their protagonists. The themes here are broad but the execution is exact. There are several moments that stand out to me, from unexpected moments of levity to bold artistic choices that are mesmerizing, like an “I’m sorry” apology that goes through every level. If you’re looking for slickly executed genre thrills with great comeuppance, don’t blink when it comes to with Blink Twice.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Heretic (2024)/ Conclave (2024)

Recently, two religious-based, single-location thrillers have emerged from the confines of indie cinema, and this combination is so rare that I felt a unique opportunity to review them both.

Heretic is a chamber movie about two teen Mormons (Sophie Thatcher, Chloe East) proselytizing to a middle-aged man (Hugh Grant) one dark and stormy night. He invites them in and seems kind and welcoming, but looks can be very deceiving. He has some very strong opinions when it comes to the nature of belief, and he will test both of these young Mormons on the faith of their convictions as he puts them through a series of trials and lectures. That last part might stun people, but Heretic is actually at its best during its lengthy lecture sequences. It might remind people of a nattering Reddit atheist being unleashed, but the movie really comes alive when Grant is challenging the roots of their belief systems as well as the historical contexts of religions. The Mormon ladies push back as well, countering some of the arguments so it’s not so one-sided. There’s a clear point of view to the movie but I wouldn’t say it’s didactic. The thrills ratchet as the two women start to fret about what this man has in store for them, how they might escape from his labyrinthine house, and how to signal for help. Unfortunately, the revelations can never quite match the fun of the mystery of motivations, and once it gets into a really convoluted place of switcheroos, then I think it loses momentum. The performances are all outstanding, led by Grant’s magnetic about-face turn as a snide villain. The same self-effacing charms he worked so well in the realm of rom-coms have a new eerie manipulative quality, luring his prey into his fiendish trap. The end attempts to go a bloodier and more ambiguous route that I don’t know it earns, but by that time, even after stalling out for the last act, Heretic won me over by virtue of its creepy convictions.

Heretic is a chamber movie about two teen Mormons (Sophie Thatcher, Chloe East) proselytizing to a middle-aged man (Hugh Grant) one dark and stormy night. He invites them in and seems kind and welcoming, but looks can be very deceiving. He has some very strong opinions when it comes to the nature of belief, and he will test both of these young Mormons on the faith of their convictions as he puts them through a series of trials and lectures. That last part might stun people, but Heretic is actually at its best during its lengthy lecture sequences. It might remind people of a nattering Reddit atheist being unleashed, but the movie really comes alive when Grant is challenging the roots of their belief systems as well as the historical contexts of religions. The Mormon ladies push back as well, countering some of the arguments so it’s not so one-sided. There’s a clear point of view to the movie but I wouldn’t say it’s didactic. The thrills ratchet as the two women start to fret about what this man has in store for them, how they might escape from his labyrinthine house, and how to signal for help. Unfortunately, the revelations can never quite match the fun of the mystery of motivations, and once it gets into a really convoluted place of switcheroos, then I think it loses momentum. The performances are all outstanding, led by Grant’s magnetic about-face turn as a snide villain. The same self-effacing charms he worked so well in the realm of rom-coms have a new eerie manipulative quality, luring his prey into his fiendish trap. The end attempts to go a bloodier and more ambiguous route that I don’t know it earns, but by that time, even after stalling out for the last act, Heretic won me over by virtue of its creepy convictions.

Conclave is an electioneering movie that places the viewer in the middle of the fraught voting process to determine the next pope of the Catholic Church. Ralph Fiennes plays a cardinal tasked with leading the conclave, the gathering of Catholic cardinals who will stay until a nominee has won a majority of their secret votes. Except it’s all not so secret as multiple candidates are openly campaigning for votes, trying to persuade different factions to support their candidacy. Each round of voting without a winner resets the field of play and leaves sides scrambling to reclaim footing. The movie is surprisingly very easy to get into, a crackling political thriller about the behind-the-scenes machinations and politicking for the highest office in the Catholic Church. There is a bevy of twists and turns and plenty of juicy revelations and betrayals, as these holy men start acting a little less holy to eliminate their competition or sully their chances. The constant churning is enough to keep things unsettled and intriguing, but there’s also a larger question for our protagonist, a man of faith who told the prior pope that he wished to leave his faith only to be denied by the pontiff for reasons we aren’t quite sure. Why did this pope specifically pick him for this position? The movie also asks deeper questions about the nature of power and leadership, namely are the people actively seeking it the right candidates for the right reasons? The very end of the movie knocked me out with a twist that I dare say nobody will rightly see coming, but it made me want to applaud. Conclave is an intelligently crafted thriller with weighty ideas and engaging performances.

Conclave is an electioneering movie that places the viewer in the middle of the fraught voting process to determine the next pope of the Catholic Church. Ralph Fiennes plays a cardinal tasked with leading the conclave, the gathering of Catholic cardinals who will stay until a nominee has won a majority of their secret votes. Except it’s all not so secret as multiple candidates are openly campaigning for votes, trying to persuade different factions to support their candidacy. Each round of voting without a winner resets the field of play and leaves sides scrambling to reclaim footing. The movie is surprisingly very easy to get into, a crackling political thriller about the behind-the-scenes machinations and politicking for the highest office in the Catholic Church. There is a bevy of twists and turns and plenty of juicy revelations and betrayals, as these holy men start acting a little less holy to eliminate their competition or sully their chances. The constant churning is enough to keep things unsettled and intriguing, but there’s also a larger question for our protagonist, a man of faith who told the prior pope that he wished to leave his faith only to be denied by the pontiff for reasons we aren’t quite sure. Why did this pope specifically pick him for this position? The movie also asks deeper questions about the nature of power and leadership, namely are the people actively seeking it the right candidates for the right reasons? The very end of the movie knocked me out with a twist that I dare say nobody will rightly see coming, but it made me want to applaud. Conclave is an intelligently crafted thriller with weighty ideas and engaging performances.

Nate’s Grades:

Heretic: B

Conclave: B+

Nosferatu (2024)

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Nate’s Grade: B

Smile 2 (2024)

In 2022, thanks to genius viral marketing and the acknowledgement how deeply unnerving happy people can be, Smile was a surprise horror smash hit. Writer/director Parker Finn expanded on a previous short film and made serious money, which meant a sequel was a given. Finn returns to lead Smile 2 to even creepier genre pastures, this time following the mental demise of a pop star, Skye Riley (Naomi Scott) trying to make sense of this malignant curse. As much as I enjoyed the first Smile for its careful development and visceral intensity, I think Smile 2 might be even better.

In 2022, thanks to genius viral marketing and the acknowledgement how deeply unnerving happy people can be, Smile was a surprise horror smash hit. Writer/director Parker Finn expanded on a previous short film and made serious money, which meant a sequel was a given. Finn returns to lead Smile 2 to even creepier genre pastures, this time following the mental demise of a pop star, Skye Riley (Naomi Scott) trying to make sense of this malignant curse. As much as I enjoyed the first Smile for its careful development and visceral intensity, I think Smile 2 might be even better.

From the opening sequence, it’s clear that we’re in the hands of a filmmaker that knows exactly what they’re doing. This is not merely another paycheck for Finn. He’s thought about how a sequel can build from its predecessor, stand on its own, incrementally build out the mythology, but mostly how to be an expertly made horror thriller designed to get under your skin. There were multiple sequences where I kept muttering variations of , “No,” or, “I don’t like that at all,” enough so that my wife in the other room would inquire what was directing these responses. Finn is tremendous at setting up the particulars of a scare sequence and allowing the audience to simmer in that anxious period of dread as we wait for something sinister to happen. He reminds me of James Wan and his ability to set up a nasty little scenario and then traps you inside awaiting the worst. There are sequences that compelled me to look away, not simply because they were overpowering, though the gore and makeup effects can best be described as impressively gross, but because the movie was finding different ways to make me uncomfortable, but in that good horror movie way. Finn’s camera makes what we should fear very clear, and his editing is precise. This is a movie that wants you to see the darkness and persistently worry about what’s coming just out of the frame.

One of my minor complaints with the first Smile was that there wasn’t much below its grinning surface. Sure, the entire premise of a curse that spreads through witnessing horrific acts of self-harm lends itself toward the discussion of how trauma begets trauma, but beyond that the first film was more reliant upon supreme craft and well-engineered scares. There’s nothing wrong with a movie that exists primarily as a thrill ride as long as those thrills deliver upon their promise. However, with Smile 2, Finn uses the character of Skye Riley as a beginning point to discuss the toxic relationships that come with fandom. It should be very obvious for every viewer that Skye is going through some serious issues. She’s overcoming addiction, physically rehabilitating her body as well as socially rehabilitating her image, and trying to learn all her new choreography for an intense world tour. This is a woman who could use a significant break. And yet, as the movie progresses, you start to sense that there is this large machinery around her that needs her to perform because that is how she makes them all money. Even her own mother-as-manager (Rosemarie DeWitt) can seem questionable as far as her motivations; is she pushing her child because she knows it’s what best for her to focus on for recovery, or is she pushing her because the tour pays for her lifestyle? As the movie progresses, the characters fret that Skye’s increasingly bizarre behavior is going to ruin the tour first and foremost, and concern for her actual well-being is secondary at best. All these people have their paychecks attached to this woman fulfilling her contractual obligations. You can also extrapolate the intense pressure the industry places on people with mental illness and self-destructive personalities to conform to standards that are unfair and often un-meetable. You might question why more pop stars don’t have head-shaving outbursts.

One of my minor complaints with the first Smile was that there wasn’t much below its grinning surface. Sure, the entire premise of a curse that spreads through witnessing horrific acts of self-harm lends itself toward the discussion of how trauma begets trauma, but beyond that the first film was more reliant upon supreme craft and well-engineered scares. There’s nothing wrong with a movie that exists primarily as a thrill ride as long as those thrills deliver upon their promise. However, with Smile 2, Finn uses the character of Skye Riley as a beginning point to discuss the toxic relationships that come with fandom. It should be very obvious for every viewer that Skye is going through some serious issues. She’s overcoming addiction, physically rehabilitating her body as well as socially rehabilitating her image, and trying to learn all her new choreography for an intense world tour. This is a woman who could use a significant break. And yet, as the movie progresses, you start to sense that there is this large machinery around her that needs her to perform because that is how she makes them all money. Even her own mother-as-manager (Rosemarie DeWitt) can seem questionable as far as her motivations; is she pushing her child because she knows it’s what best for her to focus on for recovery, or is she pushing her because the tour pays for her lifestyle? As the movie progresses, the characters fret that Skye’s increasingly bizarre behavior is going to ruin the tour first and foremost, and concern for her actual well-being is secondary at best. All these people have their paychecks attached to this woman fulfilling her contractual obligations. You can also extrapolate the intense pressure the industry places on people with mental illness and self-destructive personalities to conform to standards that are unfair and often un-meetable. You might question why more pop stars don’t have head-shaving outbursts.

Because we know that the evil entity has the power to alter our sense of sight and sound, it means the viewer must be actively skeptical about what is happening. Is this really happening? Is this sort of happening but elements are different? Or is this completely a hallucination? It makes the plot the equivalent of shifting sand, never allowing us to be comfortable or complacent. This can lead to positive and negative feelings. It keeps things lively but it can feel like the plot never really moves forward, at least in a cause-effect accumulation. It can often feel like the movie is moving in starts and stops, and if you’re not onboard for the craft, the acting, and the scares, then the results can likely feel frustrating, especially when large swaths of time are canceled out. For me, I enjoyed the extra sensory game of keeping me alert because it led to a barrage of surprises and rug pulls, some of them admittedly annoying, especially losing what amounts to maybe an entire act of the movie, but also they were a definite way to keep upending the narrative certainty. This sneaky approach also very viscerally places us in the paranoid mindset of our protagonist, as we too are unable to trust our senses and tense up with certain unsettling auditory cues. Mainly, I was having too much fun with the devious twists and turns, and some wickedly disturbing imagery from the director, that I felt like it was an ongoing thrill ride through a funhouse of insanity that kept me guessing.

In a just world, Scott (Aladdin, Charlie’s Angels) would be at the front of the pack in the discussion for the Best Actress Oscar. This woman is put through the proverbial wringer and she showcases every frayed nerve, every degenerating thought with such verve and command. It’s essentially a performance of a woman completely breaking down mentally, but Scott doesn’t just go for broke, putting every ounce of effort into inhabiting the breakdown, she creates a character that reveals herself through the breakdown. It’s not just screaming hysterics and histrionics; there are different levels to her dismantling psyche, and Scott portrays them beautifully. I felt such great levels of dread for her because of how successfully Scott was able to anchor my emotional investment. She’s also portraying different versions of Skye, and some key flashbacks reveal just how toxic her former addict self was that she’s trying to put to rest. It’s a performance about metaphorical demons and literal demons haunting a woman, as well as guilt that is eating her alive. Scott allows us the pleasure of watching a first-class performance through her shattering.

In a just world, Scott (Aladdin, Charlie’s Angels) would be at the front of the pack in the discussion for the Best Actress Oscar. This woman is put through the proverbial wringer and she showcases every frayed nerve, every degenerating thought with such verve and command. It’s essentially a performance of a woman completely breaking down mentally, but Scott doesn’t just go for broke, putting every ounce of effort into inhabiting the breakdown, she creates a character that reveals herself through the breakdown. It’s not just screaming hysterics and histrionics; there are different levels to her dismantling psyche, and Scott portrays them beautifully. I felt such great levels of dread for her because of how successfully Scott was able to anchor my emotional investment. She’s also portraying different versions of Skye, and some key flashbacks reveal just how toxic her former addict self was that she’s trying to put to rest. It’s a performance about metaphorical demons and literal demons haunting a woman, as well as guilt that is eating her alive. Scott allows us the pleasure of watching a first-class performance through her shattering.

There’s a curious motif to the movie that many will probably ignore but my wife and I fixated on, and so I feel the need to briefly discuss this so that, you too dear reader, can have this fixation as well. There are at least four scenes where Skye drinks a large bottle of water in a manner that can be best described as monstrously destructive. She drinks that bottle like a lost man in the desert finding his first drink of water. She attacks it. My best analysis is that this is a character detail about Skye’s addictive personality and sense of dependency, projecting the same all-consuming need onto water that she had previously for narcotics. One of the best laughs is when a doctor takes stock of Skye and says how dehydrated she is. Regardless, take in how desperately Skye Riley drinks and think about perhaps applying that technique next time you need a refreshing drink.

By its nightmarish conclusion, Smile 2 finds a fitting and satisfying end stop that promises a possible even bigger and more disturbing escalation for a Smile 3. Finn has established himself with two movies as a major horror filmmaker who can work within the mid-major studio system and still keep a perspective and integrity. I’m pleased that Smile 2 isn’t just more of the same old Smile, and in fact very few instances involve strangers with that signature facial expression. By the time you’re seeing the smile, it’s usually too late. I enjoyed the choice to find menace and darkness in a world of pop music brightness (the fake pop songs actually sound indistinguishable from what currently airs on the radio, bravo). I enjoyed the continuing tradition of casting famous Hollywood scions, like Jack Nicholson’s son playing Skye’s dead boyfriend (that family grin is uncanny, also bravo). What I really enjoyed was Scott’s uncompromising performance. Smile 2 has convinced me that Finn is the real deal, Scott might be one of our best modern scream queens and young actors, and to confirm introverted habits to avoid anyone who looks directly at me and smiles.

By its nightmarish conclusion, Smile 2 finds a fitting and satisfying end stop that promises a possible even bigger and more disturbing escalation for a Smile 3. Finn has established himself with two movies as a major horror filmmaker who can work within the mid-major studio system and still keep a perspective and integrity. I’m pleased that Smile 2 isn’t just more of the same old Smile, and in fact very few instances involve strangers with that signature facial expression. By the time you’re seeing the smile, it’s usually too late. I enjoyed the choice to find menace and darkness in a world of pop music brightness (the fake pop songs actually sound indistinguishable from what currently airs on the radio, bravo). I enjoyed the continuing tradition of casting famous Hollywood scions, like Jack Nicholson’s son playing Skye’s dead boyfriend (that family grin is uncanny, also bravo). What I really enjoyed was Scott’s uncompromising performance. Smile 2 has convinced me that Finn is the real deal, Scott might be one of our best modern scream queens and young actors, and to confirm introverted habits to avoid anyone who looks directly at me and smiles.

Nate’s Grade: A-

The Substance (2024)

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

Elisabeth (Demi Moore) is a television fitness instructor who has been massively popular for decades. Upon her 50th birthday, she’s promptly dismissed from her job by her studio, concerned over her diminished appeal as a sex symbol. She gets word of a mysterious elixir that can help her reverse the ravages of aging. It arrives via a clandestine P.O. box in a container with syringes and very specific instructions. She needs to spend seven days as her younger self, and seven days as her present self. She needs to “feed” her non-primary self. She also needs to understand that she is still the same person and not to get confused. Elisabeth injects herself with the serum and, through great physical duress, “Sue” emerges from her back like a butterfly sprouting from a fleshy cocoon. As Sue (Margaret Qualley), she’s now able to bask in the fame and attention that had been drifting away. Sue becomes the next hot fitness instructor and everything the studio wants. Except she’s enjoying being Sue so much that going back to her Elisabeth self feels like a punishment. Sue/Elisabeth starts to cheat the very specific rules of substance-dom, and some very horrifying results will transpire as she becomes increasingly desperate to hold onto what she has gained.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

I found the exploration of identity between Sue and Elisabeth to be really interesting, as we’re told repeatedly in the instructions that the two are the same person, and yet the two versions view the other with increasing resentment and hostility. For all intents and purposes, it’s the same woman trying on different outfits of herself, but that doesn’t stop the dissociation. In short order, the two versions view one another as rivals fighting over a shared resource/home. Sue becomes the preferred version and thus the “good times” where she can feel at her best. The older Elisabeth persona then becomes the unwanted half, and the weeks spent outside the coveted persona are akin to a depression. She keeps to herself, gorges on junk food, and anxiously counts the prolonged hours until she can finally transform into Sue. Again, this is the same character, but when she’s wearing the younger woman’s body, it can’t help but trick her into feeling like a different person. This division builds a fascinating antagonism ultimately against herself. She’s literally fighting with herself over her own body, and that sounds like pertinent social commentary to me.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

This is a first-rate body horror parable with wonderfully surreal touches throughout. The creation of Sue, being born from ripping from Elisabeth’s back, is an evocative and shocking image, as is the garish stapling of Elisabeth’s back/entry wound (why it makes for the poster’s key image). It’s reminiscent of a snake slithering out of its old skin, but to also have to take care of that old skin, knowing you have to metaphorically slide it back on, is another matter entirely. The literal dead weight is a reminder of the toll of this process but it’s also like they’ve been given a dependant. The spinal fluid injections are another squirm factor. I loved the way the Kubrickian production design heightens the unreality of the world. I won’t spoil where exactly the movie goes, but know that very bad things will happen beyond your wildest predictions. The finale is a tremendously bonkers climax that fulfills the gonzo, blood-soaked madness of the movie. If you’re a fan of inspired and disturbing body horror, The Substance cannot be missed.

Demi Moore is a fascinating selection for our lead. While it might have been inspired to have Qualley (Maid, Kinds of Kindness) play the younger version of her mother, Andie McDowell (Groundhog Day), it’s meaningful to have Moore as our aging figure of beauty standards. Here is an actress who has often been defined by her body, from the record payday she got for agreeing to bare it all in 1996’s Striptease, to the iconic Vanity Fair magazine cover of her nude and pregnant, to the roles where men are fighting over her body (Indecent Proposal), she’s using her body to tempt (Disclosure), or she’s using her body to push boundaries (G.I. Jane). It’s also meaningful that Moore has been out of the limelight for some time, mimicking the predicament for Elisabeth. Because of her personal history, the character has more meaning projected onto her, and Moore’s performance is that much richer. It reminded me of Nicolas Cage’s performance in Pig, a statement about an artist’s career that has much more resonance because of the years they can parlay into the lived-in role. Moore is fantastic here as our human face to the pressures and psychological torment of aging. She has less and less to hold onto, and in the later stretches of the movie, while Moore is buried under mountains of mutation makeup, she still manages to show the scared person underneath.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Much needs to be said about the hyperbolic sexualization of its characters, particularly Sue as the new young fitness star. Obviously our director is intending to satirize the default male gaze of the industry, as her camera lingers over tawny body parts and close-ups of curves, crevices, and crotches. However, the sexual satire is so ridiculously exploitative that it passes over from being too much and back to the sheer overkill being the point. This is not a movie of subtlety and instead one of intensity to the point that most would turn back and say, “That’s enough now.” For a movie about the perils and pleasures of the flesh, it makes sense for the photography to be as amplified in its rampant sensuality. There are segments where every camera angle feels like a thirsty glamour shot to arouse or arrest, but again this is done for a reason, to showcase Elisabeth/Sue as the world values them. The over-the-top male gaze the movie applies can be overpowering and exhausting, but I think that’s exactly Fargeat’s point: it’s reductive, insulting, and just exhausting to exclusively view women on these narrow terms. This isn’t quite our world, as the number one show on TV is an aerobics instructor, but it’s still close enough. I can understand the tone being too much for many viewers, but if you can push through, you might see things the way Fargeat does, and every lingering and exaggerated beauty shot might make you chuckle. It’s body horror on all fronts, showing the grotesquery not just in how bodies degrade but how we degrade others’ bodies.

On a personal note, while I’ll be back-dating this review, I wrote portions of it while sitting at my father’s bedside during his last days of life. He’s the person that instilled in me the love of movies, and I learned from him the shared language of cinematic storytelling, and one of my regrets is that I didn’t go see more movies with my father while we could. I really wish he could have seen The Substance because he was always hungry for new experiences, to be wowed by something he felt like he hadn’t quite seen before, to be transported to another world. He was also a fan of dark humor, ridiculous plot twists, and over-the-top violence, and I can hear his guffawing in my head now, thinking about him watching The Substance in sustained rapturous entertainment. It’s a movie that evokes strong feelings, chief among them a compulsive need to continue watching. It’s more than a body horror movie but it’s also an excellent body horror movie. Fargeat has established herself, in two movies, as an exciting filmmaker choosing to work within genre storytelling, reusing the tools of others to claim as her own with a proto-feminist spin and an absurdist grin. The Substance is the kind of filmgoing experience so many of us crave: vivid and unforgettable. And, for my money, the grossest image in the whole movie is Dennis Quaid slurping down shrimp.

Nate’s Grade: A

Tarot (2024)

In the long line of horror movies about dumb teenagers stumbling onto curses, Tarot might be one of the most ineffective and ridiculous. First off, tarot readings are so detailed and specific, while also being vague to most of us unfamiliar with what you can find on the playing cards. This means the movie must constantly remind the viewer what the fateful readings were as well as the spooky imagery. Also, being a PG-13 movie, means that the terror is kept more on a psychological bullying level, where the teens have to “face their fears” but they’re not terribly personalized. One girl finds herself in a magician’s performance for ghouls and literally hides in a box only to be sawed in half. What was the personal fear there? Stage magicians? One guy is in a subway station and comes across a newspaper with his face on it and the headline, “You Die Today” (who says print media is dead…. wait a second). This is one of those movies that suffers because the rules of the curse are sketchy at best. We don’t know the escalation or how the teens might beat it. However, I wanted to almost applaud in amazement when the script practically plays an Uno Reverse card on its angry spirit (“If she’s killing everyone because they got their horoscope read, what if WE read HER horoscope to HER, huh?!”). The entire enterprise feels transparently like some studio exec optioned the concept of a tarot deck and said, “You know, make it haunted or whatever.” Unless you’re desperate for some derisive entertainment chuckles, skip Tarot.

In the long line of horror movies about dumb teenagers stumbling onto curses, Tarot might be one of the most ineffective and ridiculous. First off, tarot readings are so detailed and specific, while also being vague to most of us unfamiliar with what you can find on the playing cards. This means the movie must constantly remind the viewer what the fateful readings were as well as the spooky imagery. Also, being a PG-13 movie, means that the terror is kept more on a psychological bullying level, where the teens have to “face their fears” but they’re not terribly personalized. One girl finds herself in a magician’s performance for ghouls and literally hides in a box only to be sawed in half. What was the personal fear there? Stage magicians? One guy is in a subway station and comes across a newspaper with his face on it and the headline, “You Die Today” (who says print media is dead…. wait a second). This is one of those movies that suffers because the rules of the curse are sketchy at best. We don’t know the escalation or how the teens might beat it. However, I wanted to almost applaud in amazement when the script practically plays an Uno Reverse card on its angry spirit (“If she’s killing everyone because they got their horoscope read, what if WE read HER horoscope to HER, huh?!”). The entire enterprise feels transparently like some studio exec optioned the concept of a tarot deck and said, “You know, make it haunted or whatever.” Unless you’re desperate for some derisive entertainment chuckles, skip Tarot.

Nate’s Grade: D+

Alien: Romulus (2024)

I will maintain that over the course of forty years that there have been no bad Alien movies. While 2017’s Alien Covenant gets the closest, I think each of the four Alien movies from 1979 to 1997 are worthy of praise for different reasons. The Alien franchise is unique among most sci-fi blockbusters in that each of its movies feels so radically different. The groundbreaking first movie is the hallowed haunted house movie in space; the 1986 sequel set the foundation for all space marine action movies, with Sigourney Weaver earning a Best Actress nomination, a real rarity for any sci-fi action movie; the much-derided third film from 1992 is much better than people give it credit for, and while flawed it has really intriguing ideas and characters with a unique setting and a gutsy ending; the fourth film from 1997 might just be the most fun, going all-in on schlocky action and colorful characters. Each of them is different with a style and tone of their own, and each is worthy of your two hours. Enter director/co-writer Fede Alvarez’s Alien: Romulus, meant to take place between the fifty-year time span between Alien and Aliens. It was intended to be a Hulu streaming movie but got called up to the big leagues of theatrical release, and while it has some underwritten aspects and clunky fan service, Romulus is another worthy sequel for a franchise that admirably keeps marching to its own beat.

It’s 2142 and life on an off-world colony isn’t exactly the adventure advertised. It’s a mining colony that’s slowly poisoning its huddled masses. Rain (Cailee Spaeny) has just finished her two-year contract only to be informed by her greedy company that, because of worker shortages, she’s locked in for another two years of indentured servitude. She’s also in charge of her adoptive brother, Andy (David Johnsson), a malfunctioning android that her late father reprogrammed. An ex-boyfriend comes back into Rain’s life with a plan: there’s an old derelict research station that they can scavenge and retrieve the cryo chambers, which can make long-term travel to a new life in a new system a possibility. There’s also a catch: they need Andy because only he can open the ship’s locked gates. The ragtag crew flies out to the derelict ship orbiting a ringed planet and, of course, discovers far more than they bargained for as the ship, of Weyland-Yutani origins, is crawling with face-hugging fiends just waiting for new faces.

Despite my grumbles, I found Alien: Romulus to be a very entertaining new entry that had the possibility of genre greatness. The setting and central character dynamic are terrific. The Alien franchise hasn’t exactly been subtle about its criticisms of multi-faceted corporations and their bottom-line priorities, but it’s even more effective to see the dinghy world of this mining colony. It’s a bleak existence of dystopian labor exploitation and you get an early sense of the desperation that motivates the characters to flee at any opportunity. Eventually, the evil corporation’s big plans for the “perfect organism,” a.k.a. the xenomorph, are to replace the depleting labor force. Humans, it turns out, aren’t built to work in space long-term, and the human cost is felt effectively in Act One. Another key part of what made the movie so immediately engaging for me is the sweet surrogate brother-sister relationship between Rain and Andy. He’s vulnerable, an older android model who needs some repairs, but he’s loyal and kind and loves pun-heavy jokes. This central relationship hooked me and gave me something to genuinely worry over as things get more dire, and it’s not just the scary aliens. Once onboard, Andy uploads the programming of a different android, and the competing objectives make him become a different person, all wonderfully played by Johnsson, who was supremely appealing in Rye Lane. While literally every other character is remarkably underwritten (this one doesn’t like robots, this one is pregnant, this one is… Buddhist?), the genuine bond between Andy and Rain grounded me.

Romulus also has some sneaky good set pieces that kept me squirming in my seat or inching closer in excitement. Alvarez (Don’t Breathe, Evil Dead) can concoct some dynamite suspense sequences and knows how to draw out the tension to pleasingly anxious perfection. This is the best Alien movie yet to really sell the danger of the springy face-huggers. There’s a taut sequence where the humans have to slow their movements to walk through a face-hugger minefield lest their spike in temperature alert the deadly creatures. There’s another later sequence that ingeniously utilizes space physics to escape the xenomorph acid blood. I loved how well it was set up and then the fun visuals of zero-gravity acid blood. The practical effects make for lots of great looking in-camera effects, and the production design is incredibly detailed while achieving a chilling overall mood of dread. Alvarez leans upon the visual frameworks of Ridley Scott and James Cameron, as who doesn’t, but finds ways to make his Alien movie his own. I really appreciated the dedication to the sprawling vistas of space, like extended shots outside the ship that really translate the sheer majesty and terrifying scale of space. The last-second threat of demolition is made all the more arresting by crashing into the rings of the planet. I think most people confuse a planet’s rings like it’s some kind of water vapor when instead it’s like a crowded highway of debris.

However, there are some misguided nods toward fan service that go overboard and become groan-inducing. There’s a fine line between homage and back-bending fan service, and Romulus skirts over occasionally into the dangerous territory, given over to references to the other movies that lack better context to make them anything more than contrived callbacks. Take for instance a triumphant killing of a xenomorph where a character utters, “Get away from her,” which itself would have sufficed, as any Alien franchise fan knows this reference point. Then the character continues, in an awkward pause, almost stumbling over the words and translating the awkwardness directly for us, as they add, “…You bitch.” Why? Why would this character need to say this exact same line (although, timeline-wise, this is now the first use of the phrase as Ripley is still in hypersleep)? The moment doesn’t call for this specific line; it could have been anything else, but they made it the line we all know from Aliens. There’s also the familiar ending where the characters think they’ve won and, wouldn’t you know it, there’s one more tussle to be had with a xenomorph who has snuck onto the escape ship. I’m less bothered by this continuation as it’s almost a formula expectation for the franchise at this point, though keeping Rain in her sleeping undies for the final fight seems like another unnecessary nod to the 1979 original. They even tie back the mysterious black goo from the Engineers via Prometheus, though as a vague power-up when, if I can recall, it was a biological weapon of mass destruction, but sure, now it’s a power-up elixir.

But the worst and most misguided act of fan service is where the movie literally brings a performer back from the dead (some spoilers ahead, beware). When Rain and the gang stroll through the derelict company ship, they discover the upper torso of a discarded android, like Ash (Ian Holm) in the original Alien. Not just like Ash because for all intents and purposes it is Ash, as the filmmakers resurrect Holm (who passed away in 2020) and use Deepfake A.I. technology to clumsily animate the man. This isn’t the first instance of a deceased actor brought back to screen by a digital double, from Fred Astaire dancing with a mop to Peter Cushing having a significant post-death supporting role in 2016’s Rogue One. Here’s the thing with just about all of these performances: they could have just been a different actor. Why did it have to be Grand Moth Tarkin (Cushing) and not just any other obsequious Empire middle manager? With Alien: Romulus, why does it have to be this specific version of an android when it could have been anyone else in the world besides the dearly departed Holm? I just can’t comprehend why the filmmakers decided to bring back Holm in order to play A DIFFERENT android who isn’t Ash but might as well be since he’s also been torn in half. Why not have the android be another version of Andy? That would have presented a more direct dichotomy for the character to have to process. The effects reanimating Holm are eerie and spotty at best, apparently built from an old scan from The Lord of the Rings. It’s just a distracting and unnecessary blunder, the inclusion of which can only be justified by trying to appeal to fans by saying, “Hey, remember this character? Even though he’s not that character. Well. Here.” We used to readily accept other actors playing the same character before the rise in technology. Nobody watching The Godfather Part II wondered why Robert DeNiro wasn’t a slimmed-down Marlon Brando.

As an Alien movie, Romulus starts off great and settles for good, but it still has several terrific set pieces, its own effectively eerie mood and style, and a grounded character dynamic that made me genuinely care, at least about two characters while the others met their requite unfortunate ends. It doesn’t have the Big Ideas of a Prometheus or the narrative arcs of Aliens, or even the go-for-broke schlock of Alien Resurrection, but Romulus delivers the goods while also feeling like its own movie, a fact I still continue to appreciate with the Alien franchise. It’s an enjoyable genre movie that fits in with the larger franchise. I wish some of the clumsy nods to fan service, especially the resurrection of a certain character, had been reeled back with more restraint to chart its own course, but it’s not enough to derail what proves to be a winning sequel.

Nate’s Grade: B

You must be logged in to post a comment.