Blog Archives

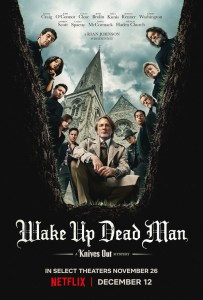

Wake Up Dead Man (2025)

Being the third in its franchise, we now have a familiar idea of what to expect from a Knives Out murder mystery. Writer/director Rian Johnson has a clear love for the whodunit mystery genre but he loves even more turning the genre on its head, finding something new in a staid and traditional style of storytelling. The original 2019 hit movie let us in on the “murderer” early, and it became more of a game of out-thinking the world-class detective, Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig). With the 2022 sequel Glass Onion, the first of Netflix’s two commissioned sequels for a whopping $400 million, Johnson reinvented the unexpected twin trope and let us investigate a den of tech bro vipers with added juicy dramatic irony. With his latest, Wake Up Dead Man, Johnson is trying something thematically different. Rather than adding a meta twist to ages-old detective tropes, Johnson is putting his film’s emphasis on building out the themes of faith. This is a movie more interested in the questions and value of faith in our modern world. It still has its canny charms and surprises, including some wonderfully daffy physical humor, but Wake Up Dead Man is the most serious and soul-searching of the trilogy thus far, and a movie that hit me where it counts.

Being the third in its franchise, we now have a familiar idea of what to expect from a Knives Out murder mystery. Writer/director Rian Johnson has a clear love for the whodunit mystery genre but he loves even more turning the genre on its head, finding something new in a staid and traditional style of storytelling. The original 2019 hit movie let us in on the “murderer” early, and it became more of a game of out-thinking the world-class detective, Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig). With the 2022 sequel Glass Onion, the first of Netflix’s two commissioned sequels for a whopping $400 million, Johnson reinvented the unexpected twin trope and let us investigate a den of tech bro vipers with added juicy dramatic irony. With his latest, Wake Up Dead Man, Johnson is trying something thematically different. Rather than adding a meta twist to ages-old detective tropes, Johnson is putting his film’s emphasis on building out the themes of faith. This is a movie more interested in the questions and value of faith in our modern world. It still has its canny charms and surprises, including some wonderfully daffy physical humor, but Wake Up Dead Man is the most serious and soul-searching of the trilogy thus far, and a movie that hit me where it counts.

In upstate New York, Pastor Jud (Josh O’Connor) has been assigned to a church to help the domineering Jefferson Wicks (Josh Brolin). The congregation is dwindling with the exception of a few diehards holding onto Wicks’ message of exclusion and division. The two pastors are ideologically in opposition, with Pastor Jud favoring a more nurturing and welcoming approach for the Christian church. Then after one fiery sermon, Wicks retires to an antechamber and winds up dead, with the primary suspect with the most motivation being Pastor Jud. Enter famous detective extraordinaire Benoit Blanc to solve the riddle.

I appreciated how the movie is also an examination on the different voices fighting for control of the direction of the larger Christian church. Wicks is your traditional fire-and-brimstone preacher, a man who sees the world as a nightmarish carnival of temptations waiting to drag down souls. He sees faith as a cudgel against the horrors of the world, and for him the church is about banding together and fighting against those outside forces no matter how few of you remain to uphold the crusade. Pastor Jud rejects this worldview, arguing that if you think of the church as a pugilist in a battle then you’ll start seeing enemies and fights to come to all places. He’s a man desperate to escape his violent past and to see the church as a resource of peace and resolution but Wicks lusts for the fight and the sense of superiority granted by his position. He relishes imposing his wrath onto others, and his small posse of his most true believers consider themselves hallowed because they’re on the inside of a special club. For Pastor Jud, he’s rejecting hatred in his heart and looks at the teachings of Jesus as an act of love and empathy. It’s not meant to draw lines and exclude but to make connections. These two philosophical differences are in direct conflict for the first half of the movie, one viewing the church as an open hand and the other as a fist. It’s not hard to see where Johnson casts his lot since Pastor Jud is our main character, after all. I also appreciated the satirical tweaks of the church’s connections to dubious conservative political dogma, like Wicks’ disciples trying to convince themselves the church needs a bully of its own to settle scores (“What is truth anyway?” one incredulously asks after some upsetting news about their patriarch). It’s not hard to make a small leap to the self-serving rationalizations of supporting a brazenly ungodly figure like Trump. At its core, this movie is about people wrestling with big ideas, and Johnson has the interest to provide space for these ideas and themes while also keeping his whodunit running along pace-for-pace.

I appreciated how the movie is also an examination on the different voices fighting for control of the direction of the larger Christian church. Wicks is your traditional fire-and-brimstone preacher, a man who sees the world as a nightmarish carnival of temptations waiting to drag down souls. He sees faith as a cudgel against the horrors of the world, and for him the church is about banding together and fighting against those outside forces no matter how few of you remain to uphold the crusade. Pastor Jud rejects this worldview, arguing that if you think of the church as a pugilist in a battle then you’ll start seeing enemies and fights to come to all places. He’s a man desperate to escape his violent past and to see the church as a resource of peace and resolution but Wicks lusts for the fight and the sense of superiority granted by his position. He relishes imposing his wrath onto others, and his small posse of his most true believers consider themselves hallowed because they’re on the inside of a special club. For Pastor Jud, he’s rejecting hatred in his heart and looks at the teachings of Jesus as an act of love and empathy. It’s not meant to draw lines and exclude but to make connections. These two philosophical differences are in direct conflict for the first half of the movie, one viewing the church as an open hand and the other as a fist. It’s not hard to see where Johnson casts his lot since Pastor Jud is our main character, after all. I also appreciated the satirical tweaks of the church’s connections to dubious conservative political dogma, like Wicks’ disciples trying to convince themselves the church needs a bully of its own to settle scores (“What is truth anyway?” one incredulously asks after some upsetting news about their patriarch). It’s not hard to make a small leap to the self-serving rationalizations of supporting a brazenly ungodly figure like Trump. At its core, this movie is about people wrestling with big ideas, and Johnson has the interest to provide space for these ideas and themes while also keeping his whodunit running along pace-for-pace.

There is a moment of clarification that is so sudden, so unexpectedly beautiful that it literally had me welling up in tears and dumbstruck at Johnson’s capabilities as a precise storyteller. It’s late into Act Two, and Blanc and Pastor Jud are in the thick of trying to gather all the evidence they can and chase down those leads to come to a conclusive answer as to how Pastor Jud is innocent. The scene begins with Pastor Jud talking on the phone trying to ascertain when a forklift order was placed. The woman on the other side of the line, Louise (Bridget Everett, Somebody Somewhere), is a chatty woman who is talking in circles rather than getting to the point, delaying the retrieval of desired information and causing nervous agitation for Pastor Jud. It’s a familiar comedy scenario of a person being denied what they want and getting frustrated from the oblivious individual causing that annoying delay. Then, all of a sudden, as the frustration is reaching a breaking point, she quietly asks if she can ask Pastor Jud a personal question. This takes him off guard but he accepts, and from there she becomes so much more of a real person, not just an annoyance over the phone. She mentions her parent has cancer and is in a bad way and she’s unsure how to repair their relationship while they still have such precious time left. The movie goes still and lingers, giving this woman and her heartfelt vulnerability the floor, and Pastor Jud reverts back to those instincts to serve. He goes into another room to provide her privacy and counsels her, leading her in a prayer.

The entire scene is magnificent and serves two purposes. This refocuses Pastor Jud on what is most important, not chasing this shaggy investigation with his new buddy Blanc but being a shepherd to others. It re-calibrates the character’s priorities and perspective. It also, subtlety, does the same for the audience. The wacky whodunit nature of the locked-door mystery is intended as the draw, the game of determining who and when are responsible for this latest murder. It’s the appeal of these kinds of movies, and yet, Johnson is also re-calibrating our priorities to better align with Pastor Jud. Because ultimately the circumstances of the case will be uncovered, as well as the who or whom’s responsible, and you’ll get your answers, but will they be just as important once you have them? Or will the themes under-girding this whole movie be the real takeaway, the real emotionally potent memory of the film? As a mystery, Wake Up Dead Man is probably dead-last, no pun intended, in the Knives Out franchise, but each movie is trying to do something radical. With this third film, it’s less focused on the twists and turns of its mystery and its secrets. It’s more focused on the challenging nature of faith as well as the empathetic power that it can afford others when they choose to be vulnerable and open.

The entire scene is magnificent and serves two purposes. This refocuses Pastor Jud on what is most important, not chasing this shaggy investigation with his new buddy Blanc but being a shepherd to others. It re-calibrates the character’s priorities and perspective. It also, subtlety, does the same for the audience. The wacky whodunit nature of the locked-door mystery is intended as the draw, the game of determining who and when are responsible for this latest murder. It’s the appeal of these kinds of movies, and yet, Johnson is also re-calibrating our priorities to better align with Pastor Jud. Because ultimately the circumstances of the case will be uncovered, as well as the who or whom’s responsible, and you’ll get your answers, but will they be just as important once you have them? Or will the themes under-girding this whole movie be the real takeaway, the real emotionally potent memory of the film? As a mystery, Wake Up Dead Man is probably dead-last, no pun intended, in the Knives Out franchise, but each movie is trying to do something radical. With this third film, it’s less focused on the twists and turns of its mystery and its secrets. It’s more focused on the challenging nature of faith as well as the empathetic power that it can afford others when they choose to be vulnerable and open.

Blanc doesn’t even show up for the first forty or so minutes, giving the narration duties to Pastor Jud setting the scene of his own. Craig (Queer) is a bit more subdued in this movie, both given the thematic nature of it as well as ceding the spotlight to his co-star. Blanc is meant to be the more stubborn realist of the picture, an atheist who views organized religion as exploitative claptrap (he seems the kind of guy who says “malarkey” regularly). His character’s journey isn’t about becoming a true believer by the end. It’s about recognizing and accepting how faith can affect others for good, specifically the need for redemption. Minor spoilers ahead. His final grand moment, the sermonizing we expect from our Great Detectives when they finally line up all the suspects and clues and knock them down in a rousing monologue, is cast aside, as Blanc recognizes his own ego could be willfully harmful and in direct opposition to Pastor Jud’s mission. It’s a performance that asks more of Craig than to mug for the camera and escape the molasses pit of his cartoonish Southern drawl. He’s still effortlessly enjoyable in the role, and may he continue this series forever, but Wake Up Dead Man proves he’s also just as enjoyable as the second banana in a story.

O’Connor (Challengers, The Crown) is our lead and what a terrific performance he delivers. The character is exactly who you would want a pastor to be: humble, empathetic, honest, and striving to do better. It’s perhaps a little too cute to call O’Connor’s performance “soulful” but I kept coming back to that word because this character is such a vital beating heart for others, so hopeful to make an impact. It’s wrapped up in his own hopes of turning his life around, turning his personal tragedy into meaning, devoting himself to others as a means of repentance. He’s a man in over his head but he’s also an easy underdog to root for, just like Ana de Armas’ character was in the original Knives Out. You want this man to persevere because he has a good moral center and because our world could use more characters like this. O’Connor has such a brimming sense of earnestness throughout that doesn’t grow maudlin thanks to Johnson’s deft touch and mature exploration of his themes. O’Connor is such a winning presence, and when he’s teamed with Blanc, the two form an enjoyable buddy comedy, each getting caught up in the other’s enthusiasm.

O’Connor (Challengers, The Crown) is our lead and what a terrific performance he delivers. The character is exactly who you would want a pastor to be: humble, empathetic, honest, and striving to do better. It’s perhaps a little too cute to call O’Connor’s performance “soulful” but I kept coming back to that word because this character is such a vital beating heart for others, so hopeful to make an impact. It’s wrapped up in his own hopes of turning his life around, turning his personal tragedy into meaning, devoting himself to others as a means of repentance. He’s a man in over his head but he’s also an easy underdog to root for, just like Ana de Armas’ character was in the original Knives Out. You want this man to persevere because he has a good moral center and because our world could use more characters like this. O’Connor has such a brimming sense of earnestness throughout that doesn’t grow maudlin thanks to Johnson’s deft touch and mature exploration of his themes. O’Connor is such a winning presence, and when he’s teamed with Blanc, the two form an enjoyable buddy comedy, each getting caught up in the other’s enthusiasm.

Johnson has assembled yet another all-star collection of actors eager to have fun in his genre retooling. Some of these roles are a little more thankless than others (Sorry Mila Kunis and Thomas Haden Church, but it was nice of you to come down and play dress-up with the rest of the cast). The clear standout is Glenn Close (Hillbilly Elegy) as Martha, the real glue behind Wicks’ church as well as an ardent supporter of his worldview of the damned and the righteous. She has a poignant character arc coming to terms with how poisonous that divisive, holier-than-thou perspective can be. Close is fantastic and really funny at certain parts, giving Martha an otherworldly presence as a woman always within earshot. Brolin (Weapons) is equally fun as the pugnacious Wicks, a man given to hypocrisy but also resentful of others who would reduce his position of influence. The issue with Wake Up Dead Man is that elevating Pastor Jud to co-star level only leaves so much room for others, and so the suspect list is under-served, arguably wasted, especially Andrew Scott (All of Us Strangers) as a red-pilled sci-fi writer looking for a comeback. The best of the bunch is Daryl McCormack (Good Luck to You, Leo Grande) as a conniving wannabe in Republican politics trying to position himself for a pricey media platform and Cailee Spaeny (Alien: Romulus) as a cellist who suffers from deliberating pain and was desperate for a miracle delivered by Wicks. He’s the least genuine person, she’s hoping for miraculous acts, and both will be disappointed from what they seek.

Wake Up Dead Man (no comma in that title, so no direct command intended) is an equally fun movie with silly jokes and a reverent exploration of the power of faith and its positive impact, not even from a formal religious standpoint but in the simple act of connecting to another human being in need. This is the richest thematically of the three Knives Out movies but it also might be the weakest of the mysteries. The particulars of the case just aren’t as clever or as engaging as the others, but then again not every Agatha Christie mystery novel could be an absolute all-time ripper. That’s why the movie’s subtle shifts toward its themes and character arcs as being more important is the right track, and it makes for a more emotionally resonant and reflective experience, one that has replay value even after you know the exact particulars of the case. If you’re a fan of the Knives Out series, there should be enough here to keep you enraptured for more. Because of that added thematic richness, Wake Up Dead Man has an argument as the best sequel (yet).

Nate’s Grade: A-

Heart of Stone (2023)

Heart of Stone is pre-molded for the Netflix formula of star-driven action vehicles and spy thrillers that are meant to pass the time and do little else to stimulate your thinking or entertainment. These expensive and generally disappointing genre movies feel remote and mechanical, as if the almighty Netflix algorithm thought, after housing and documenting thousands of action movies, that it too could make a competent spy thriller.

Heart of Stone is pre-molded for the Netflix formula of star-driven action vehicles and spy thrillers that are meant to pass the time and do little else to stimulate your thinking or entertainment. These expensive and generally disappointing genre movies feel remote and mechanical, as if the almighty Netflix algorithm thought, after housing and documenting thousands of action movies, that it too could make a competent spy thriller.

Rachel Stone (Gal Gadot) belongs to MI-6 but also another organization, The Charter. They’re a clandestine peace keeping force powered by a super A.I. known as The Heart. Super hacker Keya (Alia Bhatt, RRR) is after the Heart, and she’ll wreck havoc until she gets it.

There are plenty of recognizable genre elements and inspirations here, but the problem with Heart of Stone is that it never gets beyond feeling like another bland summation of its formula-laden parts. You’ve seen bits and pieces of this movie before, so the viewing experience becomes a personal guessing game of how long it will take for Heart of Stone to utilize this genre cliche or that cliche. There’s no surprise or verve or quirk to be had here. Everything is pulled from a big bucket of cliches and then reassembled to best simulate a genre movie that you mostly remember seeing before. This lack of effort and finesse can make the movie quite a slog to sit through. The lack of imagination translates even to its generic title. See, her last name is Stone, and she works for a secret organization where people have code names after playing cards. Do you get it? This clunky name generator title feels like something that some feeble social media post would ask as it really intends to steal your identity from security questions.

I keep going back to the very core construction of the plot and scratching my head in confusion. Stone is part of MI-6, a spy agency, but she’s also part of ANOTHER even more secret spy agency, which she must keep secret from her fellow secret keepers already doing their spy thing. Why do we need the extra layer of subterfuge? What does this add? The situation where the very deadly and skilled person is hiding in plain sight, the Superman pretending to be the bumbling Clark Kent, is already there with her being a hidden spy, so why do we need a second layer? It’s a complication that doesn’t add anything of value. She’s already on a mission and getting tech help from her own spy team and agency, and she’s also given even more secret tech help from the other more secret spy agency. It’s redundant. It’s not like TV’s Alias or Hydra in the Marvel movies where there was an opposition force within the spy agency, actively working against its aims. It also has the detriment of prolonging the eventual revelation and inevitable betrayal from within the team (don’t act like you didn’t see this coming from the opening mission). We all know it’s coming, so then I think that perhaps the filmmakers will use this extra time with these co-workers to better develop them, give them intriguing dimensions, or at least complicate the relationships with our protagonist who is actively lying to them about who she is. Nope. She does take care of one guy’s cat.

I keep going back to the very core construction of the plot and scratching my head in confusion. Stone is part of MI-6, a spy agency, but she’s also part of ANOTHER even more secret spy agency, which she must keep secret from her fellow secret keepers already doing their spy thing. Why do we need the extra layer of subterfuge? What does this add? The situation where the very deadly and skilled person is hiding in plain sight, the Superman pretending to be the bumbling Clark Kent, is already there with her being a hidden spy, so why do we need a second layer? It’s a complication that doesn’t add anything of value. She’s already on a mission and getting tech help from her own spy team and agency, and she’s also given even more secret tech help from the other more secret spy agency. It’s redundant. It’s not like TV’s Alias or Hydra in the Marvel movies where there was an opposition force within the spy agency, actively working against its aims. It also has the detriment of prolonging the eventual revelation and inevitable betrayal from within the team (don’t act like you didn’t see this coming from the opening mission). We all know it’s coming, so then I think that perhaps the filmmakers will use this extra time with these co-workers to better develop them, give them intriguing dimensions, or at least complicate the relationships with our protagonist who is actively lying to them about who she is. Nope. She does take care of one guy’s cat.

Another element that made little sense to me was the chosen villain. Spy and action movies lend themselves to larger-than-life characters that aim at world destruction and big swings. This movie introduces us to a super hacker who excelled in her field. Okay, and? The character feels more like a hostage than the antagonist that is masterminding the world-trotting schemes. There’s nothing of interest to this Keya character; she’s practically amorphous, so poorly defined that any other character can project onto her. I kept waiting for the motivation for why she’s resorted to her schemes, what she would want to do with the secret supercomputer, something to better add dimension or at least context for this character. Her motivation is just as frustratingly vague as the rest of her, as it’s revealed quite late that she wants the supercomputer to right the wrongs of the world, though what exactly those are, and whether she has a personal connection, who knows? She’s so bland as a villain that (mild spoilers) when she’s eventually deposed by another villain, I felt a little surge of relief that maybe someone else could do better villainy.

Even familiar genre movies can be saved with well constructed and exciting action, like those Chris Hemsworth Extraction movies that coast off the fumes of the most tortured military action cliches. Alas, there is no relief for Heart of Stone. The action is supremely bland and lacking better connections to the characters and their plights. It’s usually just chases and shootouts. There’s one sequence that takes place inside a floating satellite station, and I thought that for once things might get interesting. The subsequent action is just another fist fight and beating the other person to grab a thing before everything explodes from a gas leak. This could have just as easily taken place in a warehouse or a boat or a house or a basement or anywhere. Why introduce a fantastical setting and then ignore utilizing those unique aspects? I guess it does lead to a debris chase that reminded me of Black Widow’s finale. There is a mid-movie chase through the streets of Libson that has some life to it as we watch cars careen at high speeds, but it’s also nothing we haven’t seen before and better in a dozen other movies with more conviction than this one.

Gadot has rocketed to fame from her Wonder Woman status and she can be a charming screen presence, but let’s acknowledge there are definite acting limitations as well. I challenge you, dear reader, to think of a beloved Gadot performance outside of her Amazonian warrior woman. Were you floored from Triple 9? Or Keeping Up with the Joneses? Or Death on the Nile? There’s a reason the producers decided to just make everyone on Wonder Woman’s ancient island mirror Gadot’s Israeli accent. With that said, Gadot seems so thoroughly bored here. It might be the groan-inducing dialogue that confuses what constitutes banter and quips; take for instance a moment when a member of the spy team remarks about her haphazard driving, “Are you trying to kill us?” and Gadot woodenly replies, “Actually quite the opposite.” The movie is filled with these lackluster quotes and genre buzzwords but without any real meaning behind the words. It’s a movie going through the motions, and Gadot is following suit. It’s not that she’s bad here. She’s never asked to really try.

Gadot has rocketed to fame from her Wonder Woman status and she can be a charming screen presence, but let’s acknowledge there are definite acting limitations as well. I challenge you, dear reader, to think of a beloved Gadot performance outside of her Amazonian warrior woman. Were you floored from Triple 9? Or Keeping Up with the Joneses? Or Death on the Nile? There’s a reason the producers decided to just make everyone on Wonder Woman’s ancient island mirror Gadot’s Israeli accent. With that said, Gadot seems so thoroughly bored here. It might be the groan-inducing dialogue that confuses what constitutes banter and quips; take for instance a moment when a member of the spy team remarks about her haphazard driving, “Are you trying to kill us?” and Gadot woodenly replies, “Actually quite the opposite.” The movie is filled with these lackluster quotes and genre buzzwords but without any real meaning behind the words. It’s a movie going through the motions, and Gadot is following suit. It’s not that she’s bad here. She’s never asked to really try.

The conclusion of this review is as good a place as any to talk about the implications of the story, something that Heart of Stone doesn’t seem slightly interested in. The “heroes” of the super secret spy agency have a supercomputer that makes scarily accurate predictions, enough so that the spy agency takes them on blind faith as operating orders. Nobody really asks whether this is a good thing, except for a scant reference by our antagonist before they decide to jump ship and join Team Follow the A.I. Nobody explores the more existential question of whether these things are accurate because the machine was right or because the people were just doing what the machine said, thus making these things become accurate because of the engineering direction. There’s a Minority Report aspect about free will and abdicating this to machines that is begging to be better explored. Unfortunately, this all-knowing supercomputer is just any other disposable spy thriller element jumbled together to best resemble another disposable product. I read that Netflix intended for this to be the start of a franchise, and without an intriguing world, lead character, spy agency, or set of ongoing conflicts, it’s hard for me to envision anything Heart of Stone could offer that people would request a return visit. If you need something loud and derivative to take a drowsy nap to, then Heart of Stone is the next The Grey Man.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Hillbilly Elegy (2020)/ Feels Good Man (2020)

Hillbilly Elegy is based upon the memoir by JD Vance and in 2016 it became a hot commodity in the wake of Trump’s surprising electoral ascent, with liberals seeing it as a Rosetta Stone to understanding just how so many working-class white people could vote for a billionaire with a gold toilet. The movie, directed by Ron Howard (Apollo 13) and currently available on Netflix, follows an adult JD (Gabriel Basso). He’s a Yale law candidate forced to go back home to Middletown, Ohio after his mother Bev (Amy Adams) lands in the hospital for a heroin overdose. It’s 2011, and Bev has been fighting a losing battle with opioids for over a decade, costing her a string of boyfriends and jobs. JD’s homecoming isn’t quite so rosy. While he can take comfort in fried bologna sandwiches and his sister (Haley Bennett), the town is not what it once was. The factory has closed, poverty is generational, and his mother is one of many struggling to stay clean. In flashback, we watch MeeMaw (Glenn Close) take in the young JD (Owen Asztalos) and raise him on the right path. JD must decide how far the bonds of family go and how much he may be willing to forgive his mother even if she can never ask for help.

Hillbilly Elegy is based upon the memoir by JD Vance and in 2016 it became a hot commodity in the wake of Trump’s surprising electoral ascent, with liberals seeing it as a Rosetta Stone to understanding just how so many working-class white people could vote for a billionaire with a gold toilet. The movie, directed by Ron Howard (Apollo 13) and currently available on Netflix, follows an adult JD (Gabriel Basso). He’s a Yale law candidate forced to go back home to Middletown, Ohio after his mother Bev (Amy Adams) lands in the hospital for a heroin overdose. It’s 2011, and Bev has been fighting a losing battle with opioids for over a decade, costing her a string of boyfriends and jobs. JD’s homecoming isn’t quite so rosy. While he can take comfort in fried bologna sandwiches and his sister (Haley Bennett), the town is not what it once was. The factory has closed, poverty is generational, and his mother is one of many struggling to stay clean. In flashback, we watch MeeMaw (Glenn Close) take in the young JD (Owen Asztalos) and raise him on the right path. JD must decide how far the bonds of family go and how much he may be willing to forgive his mother even if she can never ask for help.

The subtitle of Vance’s novel was “A Memoir of a Family and a Culture in Crisis,” and it’s that latter part that got the most attention for the book and critical examination. Many a think piece was born from Vance’s best-selling expose on the hardscrabble beginnings of his personal story along the hills of Kentucky and the Ohio River Valley and his recipe for success. Given his libertarian political leanings, it’s not a surprise that his solutions don’t involve a more interventionist government and social safety nets. According to Vance’s book, he saw poverty as self-perpetuating and conquerable. It was the “learned helplessness” of his fellow Rust Belt inhabitants that Vance saw as their downfall. For me, this seems quite lacking in basic empathy. You see these people aren’t poor because they’ve been betrayed by greedy corporations, indifferent politicians, a gutted infrastructure and educational system in rural America, pill mills flooding Appalachia with cheap opioids, and a prison system that incentivizes incarceration over rehabilitation. For Vance and his like-minded fellows, upward mobility is a matter of mind over matter, and these working-class folks have just given up or won’t work as hard as before.

Now, as should be evident, I strongly disagree with this cultural diagnosis, but at least Vance is trying to use his own story as a launching point to address larger points about a portion of America that feels forgotten. The movie strips all of this away. Screenwriter Vanessa Taylor (The Shape of Water) juggles multiple timelines and flashbacks within flashbacks as Vance follows the formula of prodigal son returning back to his home. The entire draw of the book, its purported insights into a culture too removed from the coastal elites, is replaced with a standard formula about a boy rediscovering his roots and assessing his dysfunctional family. At this rate, I’m surprised they didn’t even time it so that Vance was returning home for Thanksgiving.

Now, as should be evident, I strongly disagree with this cultural diagnosis, but at least Vance is trying to use his own story as a launching point to address larger points about a portion of America that feels forgotten. The movie strips all of this away. Screenwriter Vanessa Taylor (The Shape of Water) juggles multiple timelines and flashbacks within flashbacks as Vance follows the formula of prodigal son returning back to his home. The entire draw of the book, its purported insights into a culture too removed from the coastal elites, is replaced with a standard formula about a boy rediscovering his roots and assessing his dysfunctional family. At this rate, I’m surprised they didn’t even time it so that Vance was returning home for Thanksgiving.

Removed of relevant social commentary, Hillbilly Elegy becomes little more than a gauzy, awards-bait entry meant to uplift but instead can’t help itself from being overwrought poverty porn. If we’re not looking at the bigger picture of how Appalachia got to be this way, then Vance becomes less our entry point into a world and more just an escaped prisoner. Except the movie doesn’t raise Vance up as exceptional and instead just a regular guy who pulled himself up by his bootstraps through will and family support. I’m not saying he is exceptional, I don’t know the man, but this approach then ignores the reality of why so many others just aren’t following his footsteps of simply trying harder. Without granting a more empathetic and careful understanding of the circumstances of poverty, Howard has made his movie the equivalent of a higher-caliber Running with Scissors, a memoir about a young man persevering through his “quirky, messed up family” to make something of himself on the outside. This reductive approach is meant to avoid the trappings of social commentary, and yet in trying to make his film studiously apolitical to be safer and more appealing, Howard has stumbled into making Hillbilly Elegy more insulting to its Appalachia roots. Systemic poverty is seen as a choice, as people that just aren’t trying as hard, that have given up and accepted their diminished fates. Never mind mitigating economic, psychotropic, and educational circumstances. I imagine Howard wanted to deliver something along the lines of Winter’s Bone, unsparing but deeply aware of its culture, but instead the movie is far more akin to a sloppy compilation of Hallmark movies and catchy self-deprecating bumper sticker slogans. Seriously, about every other line of dialogue feels like it was meant to be on a T-shirt, from “Where we come from is who we are, but we choose every day who we become,” to, “There are three types of people in this world: good Terminators, bad Terminators, and neutral.” Well, maybe not that last one. The insights are fleeting and surface-level, with vague patronizing along the fringes.

The personal story of J.D. Vance takes the center stage and yet he’s the biggest blank of characters, and what we do get isn’t exactly that encouraging. I think we’re meant to engage with his triumph over adversity, but he has such disdain for his background while clinging to it as an identity, and this intriguing dichotomy is never explored. Vance as a character is merely there. His awkward experiences relating to the rich elites are just silly. He calls his girlfriend (Freida Pinto) in a panic over what fork to use at a fancy dinner table, as if this perceived social faux pau would be the difference between getting a law firm gig. He’s supposed to feel like an outsider, both at home and away, unable to escape his past that defines him, but the movie doesn’t even make Vance feel alive in the present. Most of the movie he is just there while big acting takes place around him. He listens to the life lessons bestowed upon him, good and bad, and it makes him the kind of man that when he grows up will join Peter Thiel’s venture capital firm, so hooray? I sighed when the movie established the stakes as he needs to get back in time for his big lawyer job interview, a literal family vs. future crossroads. The movie treats its frustrating main character as a witness to history rather than an active participant, and his personal growth is what? Coming to terms with the limitations of his mother? Accepting himself? Leaving them all behind to survive? I don’t know. There is literally a montage where he gets his life back on track, starts getting better grades, ditches his no-good friends, and heads out into the world. This could have been a better articulated character study but instead Vance comes across as much a tourist to this downtrodden world and eager to return to safer confines as any morbidly curious viewer at home.

I simply felt bad for the actors. This is the kind of movie where subtlety isn’t exactly on the agenda, so I expected big showcases of big acting with all capitals and exclamation marks, and even that didn’t prepare me. I watched as Amy Adams (Vice) worked her mouth around an accent that always seemed elusive, with a character that veered wildly depending upon the timing of a scene. Almost every moment with Bev ends in some alarming escalation or outburst, like when a new puppy ends with Bev declaring she will “kill that dog in front of you,” or a ride back home descends into a high-speed promise of killing herself and child out of spite. This woman is troubled, to say the least, and her addictions and mental illness are what defines the character. With that guiding her, Adams is left unrestrained and usually screaming. There’s just so much screaming and wailing and crying and shouting. It’s an off-the-mark performance that reminded me of Julianne Moore in 2006’s Freedomland, where a usually bulletproof actress is left on her own in the deep end, and the resulting struggle leans upon histrionics. Was I supposed to feel sympathy for Bev at some point? Does the movie ever feel sympathy for this woman who terrorizes and beats her child? The broad portrayal lacks humanizing nuance, so Bev feels less like a symbolic victim of a larger rot of a society abandoned and betrayed and more a TV movie villain.

I simply felt bad for the actors. This is the kind of movie where subtlety isn’t exactly on the agenda, so I expected big showcases of big acting with all capitals and exclamation marks, and even that didn’t prepare me. I watched as Amy Adams (Vice) worked her mouth around an accent that always seemed elusive, with a character that veered wildly depending upon the timing of a scene. Almost every moment with Bev ends in some alarming escalation or outburst, like when a new puppy ends with Bev declaring she will “kill that dog in front of you,” or a ride back home descends into a high-speed promise of killing herself and child out of spite. This woman is troubled, to say the least, and her addictions and mental illness are what defines the character. With that guiding her, Adams is left unrestrained and usually screaming. There’s just so much screaming and wailing and crying and shouting. It’s an off-the-mark performance that reminded me of Julianne Moore in 2006’s Freedomland, where a usually bulletproof actress is left on her own in the deep end, and the resulting struggle leans upon histrionics. Was I supposed to feel sympathy for Bev at some point? Does the movie ever feel sympathy for this woman who terrorizes and beats her child? The broad portrayal lacks humanizing nuance, so Bev feels less like a symbolic victim of a larger rot of a society abandoned and betrayed and more a TV movie villain.

Close (The Wife) disappears into the heavy prosthetics and baggy T-shirts of MeeMaw, but you could have convinced me the character was a pile of coats come to life. Truthfully, MeeMaw is, by far, the most interesting character and the story would have greatly benefited from being re-calibrated from her painful perspective. She’s the one who bears witness to just how far Middletown has fallen since her and PawPaw ventured as young adults with the promise of a secure new life thanks to the thriving factory. She’s the one symbolizing the past and its grip as the present withers. She’s the one who has a history of abuse only to watch her daughter fall into similar patterns. Think of the guilt and torment and desire to rescue her grandson for a better life and save her family. That’s an inherently interesting perspective, but with JD Vance as our mundane lead, MeeMaw is more a slow-walking curmudgeon taken to doling out profane one-liners and grumpy life lessons. Close is easily the best part of Hillbilly Elegy and deserved more attention and consideration. A moment where she clings to JD’s high-scoring math test like a life raft is heartfelt and earned, more so than anything with JD.

Another slice of America that feels forgotten and angry is on display with the documentary Feels Good Man, a.k.a. the Pepe the Frog documentary. Who is Pepe? He’s a cartoon frog created by Matt Furie as part of a comic series of post-college ennui between four friends. The character was adopted by the commenters on the message board 4Chan as their own symbol, and as their memes spread and became more popular with mainstream suers, and that’s when the 4Chan warriors had to do something drastic to save their favorite frog. They began transforming Pepe into a symbol of hate in order to make him toxic for outside use, and then the irony of their attempts at reclamation faded away and Pepe became a real symbol for Neo-Nazis and white supremacists. The character is currently listed on the Anti-Defamation League’s list of symbols of hate. The movie explores this evolution and de-evolution of Matt Furie’s creation and serves as a cautionary tale about the scary shadows of Internet culture and the nature of reclaiming meaning and intent with art.

Another slice of America that feels forgotten and angry is on display with the documentary Feels Good Man, a.k.a. the Pepe the Frog documentary. Who is Pepe? He’s a cartoon frog created by Matt Furie as part of a comic series of post-college ennui between four friends. The character was adopted by the commenters on the message board 4Chan as their own symbol, and as their memes spread and became more popular with mainstream suers, and that’s when the 4Chan warriors had to do something drastic to save their favorite frog. They began transforming Pepe into a symbol of hate in order to make him toxic for outside use, and then the irony of their attempts at reclamation faded away and Pepe became a real symbol for Neo-Nazis and white supremacists. The character is currently listed on the Anti-Defamation League’s list of symbols of hate. The movie explores this evolution and de-evolution of Matt Furie’s creation and serves as a cautionary tale about the scary shadows of Internet culture and the nature of reclaiming meaning and intent with art.

Firstly, is there enough material here for a full-fledged documentary? We’re talking about a cartoon frog filling up the memes of Internet trolls. Is that enough? I think so, though I wish the movie shed even more critical scrutiny upon the 4Chan fringes of the Internet that have become a toxic cesspool of alienation and recrimination. These are people that self-identify and celebrate their social isolationism. The acronym N.E.E.T. stands for NOT Employed, Educated, or Trained and is adopted by many as an odd badge of honor. We even see home video footage of people sharing their personal lives in cluttered, trash-strewn basements. These are people electing not to engage with a larger functioning society and yet also feeling hostile to those that choose otherwise. Maybe it’s all a big joke to them, so why even bother; maybe it’s a defeatist mentality that plays upon social anxiety and learned helplessness. Maybe it’s just a noisy, nihilistic club that doesn’t want anything for themselves other than to disrupt others. The interview subjects from the 4Chan community are few but offer chilling peeks into this subculture. They see the world in terms of a very high school-level of social hierarchy, and the people who are pretty, successful, and having sexual relationships are the “popular kids” keeping them down. I think in terms of a Venn diagram, that incels and these NEET freaks are a flat circle. It almost feels like Vance’s cultural critiques of his poor Appalachia roots syncs up with the disenchanted 4Chan kids. This self-imposed isolation and self-persecution stews into a hateful mess of resentment. It’s not a surprise that several mass shooters have partaken in 4Chan and 8Chan communities.

This scary subsection of Internet culture has been left to fester and it went next level for the 2016 presidential election. The trolls recognized their own sensibilities in Donald Trump, a candidate whose entire presidency seemed on the precipice of being a bad joke. The alt-right celebrated the man and used Pepe as a symbol for Trump’s trolling of norms and decorum, and the 4Chan message boards became an army of meme makers to steer Internet chatter. It’s hard to say what exactly the cumulative effect of these memes and trolling efforts achieved, in addition to the successful efforts of Russian hackers and a media environment that gave Trump billions of dollars in free airtime, but the 4Chan crowd celebrated their victory. “We memed him to the White House,” they declared. From there, Pepe became a synonymous symbol of a newly emboldened white supremacist coalition and any pretenses of ironic detachment dissolved away.

This scary subsection of Internet culture has been left to fester and it went next level for the 2016 presidential election. The trolls recognized their own sensibilities in Donald Trump, a candidate whose entire presidency seemed on the precipice of being a bad joke. The alt-right celebrated the man and used Pepe as a symbol for Trump’s trolling of norms and decorum, and the 4Chan message boards became an army of meme makers to steer Internet chatter. It’s hard to say what exactly the cumulative effect of these memes and trolling efforts achieved, in addition to the successful efforts of Russian hackers and a media environment that gave Trump billions of dollars in free airtime, but the 4Chan crowd celebrated their victory. “We memed him to the White House,” they declared. From there, Pepe became a synonymous symbol of a newly emboldened white supremacist coalition and any pretenses of ironic detachment dissolved away.

The rise and mutation of Pepe makes up most of the movie, and it’s certainly the most fascinating and scary part of Feels Good Man. However, there is a larger question about the ownership of art and interpretation that the movie presents without conclusive answers. Symbols are a tricky thing. They’re not permanent. The swastika wasn’t always associated with Hitler and Nazis. A pentagram has significantly different meanings depending upon a Wiccan and conservative Christian audience. Feels Good Man examines Furie as a humble albeit slightly naïve creator. He’s a nice guy who just can’t get his head around what has happened to his creation. How far does the artist’s intent go when it comes to credible meaning? At one point, Furie tried stemming the negativity by killing off Pepe in a limited comic, but it didn’t matter. The 4Chan followers simply remade him as they desired because at that point Pepe was their own. He has been built and rebuilt over and over again, that no one person can claim interpretative supremacy. Furie’s version of Pepe might be gone but there are millions of others alive and well. This gets into the nature of art and how every creator in some regard must make amends with letting go of their creation. Once it enters the larger world for consumption, they can steer conversations but art can take on its own life. The last third of the movie follows Furie taking action to enforce his copyright law to push back against the more outlandish uses of Pepe the frog, including from InfoWars’ Alex Jones, the same man who told us the government was making frogs gay for some unexplained conspiracy. Jones makes for a pretty easy villain to enjoy seeing defeated, and the conclusion of the movie involves dueling taped depositions between Furie and Jones over intellectual trademarks and free speech. It makes for an easy to navigate victory for Furie to end the movie upon, but is this larger war winnable? I have my doubts and I don’t think the trolls of the darker reaches of the Internet are going away.

I also want to single out the beautiful animation that appears throughout Feels Good Man, giving a visual representation to Pepe in a manner that’s like trying to give him a say in his own intent.

So, dear reader, why did I pair both of these movies for a joint review? I found both of them as investigations into a sliver of America that feels forgotten, left behind, stuck in ruts outside their control, and resentful of a changing culture they see as exclusive to their hard-hit communities. I thought both Hillbilly Elegy and Feels Good Man could provide me, and others, greater insight into these subcultures and perhaps solutions that can make them feel more seen and heard. The problem is that Elegy doesn’t provide solutions other than “pull up your bootstraps” and Feels Good Man involves a destructive coalition that I don’t want better seen and heard. Both movies in their own ways deal with the nature of how very human it can be to retreat to their safe confines of people who too feel ostracized, hurt, and overwhelmed. I have pity for the people of the Rust Belt, the hillbillies experiencing generational poverty and hardships, though “economic anxiety” is not simply a regional or whites-only worry. I have less pity for the basement trolls of 4Chan trying to celebrate school shooters because it’s somehow funny. I’m amazed that so many talented people were part of Hillbilly Elegy and had such high hopes. For all of its full-tilt screaming, the movie is thoroughly boring and formulaic. Given the nature of an elegy, I was expecting Howard’s movie would be more considerate of its people, but their humanity is lost in this pared-down characterization, and the tragedy of society failing its own becomes an inauthentic Horatio Alger story of the plucky kid who went to Yale and became a real somebody. Feels Good Man might not be the best documentary but it feels more authentic and owns up to its inability to answer larger questions about human behavior, art, and interpretation. Both of these movies will prove horrifying to watch but only one is intentionally so.

So, dear reader, why did I pair both of these movies for a joint review? I found both of them as investigations into a sliver of America that feels forgotten, left behind, stuck in ruts outside their control, and resentful of a changing culture they see as exclusive to their hard-hit communities. I thought both Hillbilly Elegy and Feels Good Man could provide me, and others, greater insight into these subcultures and perhaps solutions that can make them feel more seen and heard. The problem is that Elegy doesn’t provide solutions other than “pull up your bootstraps” and Feels Good Man involves a destructive coalition that I don’t want better seen and heard. Both movies in their own ways deal with the nature of how very human it can be to retreat to their safe confines of people who too feel ostracized, hurt, and overwhelmed. I have pity for the people of the Rust Belt, the hillbillies experiencing generational poverty and hardships, though “economic anxiety” is not simply a regional or whites-only worry. I have less pity for the basement trolls of 4Chan trying to celebrate school shooters because it’s somehow funny. I’m amazed that so many talented people were part of Hillbilly Elegy and had such high hopes. For all of its full-tilt screaming, the movie is thoroughly boring and formulaic. Given the nature of an elegy, I was expecting Howard’s movie would be more considerate of its people, but their humanity is lost in this pared-down characterization, and the tragedy of society failing its own becomes an inauthentic Horatio Alger story of the plucky kid who went to Yale and became a real somebody. Feels Good Man might not be the best documentary but it feels more authentic and owns up to its inability to answer larger questions about human behavior, art, and interpretation. Both of these movies will prove horrifying to watch but only one is intentionally so.

Nate’s Grades:

Hillbilly Elegy: C-

Feels Good Man: B

Evening (2007)

A chick flick crammed with lots of bona fide stars and A-list talent that manages to squander all talent. It slogs on and on, the back and forth nature of the plot does little to keep an audience alert, and the story it tells in the past is so pedestrian, so minuscule, and ultimately so mundane that you can’t help but wonder why an old woman on her deathbed would be flashing back and remembering it. This high profile weepy never finds the right tone and often settles for maudlin and predictable plot turns. Evening is the kind of movie that kills the chances for a large, female-driven film to get made in Hollywood.

A chick flick crammed with lots of bona fide stars and A-list talent that manages to squander all talent. It slogs on and on, the back and forth nature of the plot does little to keep an audience alert, and the story it tells in the past is so pedestrian, so minuscule, and ultimately so mundane that you can’t help but wonder why an old woman on her deathbed would be flashing back and remembering it. This high profile weepy never finds the right tone and often settles for maudlin and predictable plot turns. Evening is the kind of movie that kills the chances for a large, female-driven film to get made in Hollywood.

Nate’s Grade: C-

You must be logged in to post a comment.