Blog Archives

Saturday Night (2024)/ September 5 (2024)

Recently two ensemble dramas were thought to have awards potential that never materialized, and I think I might know at least one reason why: they are both undone by decisions of scope to focus on either a single day or a 90-minute period to encapsulate their drama.

With Saturday Night, we follow show creator Loren Michaels (Gabriel LaBelle) the night before the premiere episode of the iconic sketch TV series, Saturday Night Live. The story is told in relative real time covering the last 90 minutes before its initial 11:30 PM EST debut in 1975. We watch Michaels try and deal with squabbling cast members, striking union members, failing technology, his ex-wife (Rachel Sennot) who also happens to be a primary producer of the show, muppets, and studio bosses that are doubtful whether this project will ever make it to air. I understand in essence why the real-time setting is here to provide more pressure and urgency as Michaels is literally running out of time. The problem is that we know the show will be a success, so inventing doubtful older TV execs to add extra antagonists feels like maybe the framing by itself was lacking. Think about Air but you added a fictional exec whose only purpose was to say, “I don’t think this Michael Jordan guy will ever succeed.” There are interesting conflicts and subplots, especially with the different groups that Michaels has to manage, but when it’s all stuffed in such a tight time frame, rather than making the movie feel more chaotic and anxious, it makes those problems and subplots feel underdeveloped or arbitrary. I would relish a behind-the-scenes movie about SNL history but the best version of that would be season 11, the “lost season,” when Michaels came back to save the show and there were legitimate discussions over whether to cancel the show. Admittedly, we would already know the show survives, but does the public know what happened to people like Terry Sweeney and Danitra Vance? Does the public know what kind of sacrifices Michaels had to make? That’s the SNL movie we deserve. Alas, Saturday Night is an amiable movie with fun actors playing famous faces, but even the cast conflicts have to be consolidated to the confined time frame. This is a clear-cut example where the setting sabotages much of what this SNL movie could have offered for its fans.

With Saturday Night, we follow show creator Loren Michaels (Gabriel LaBelle) the night before the premiere episode of the iconic sketch TV series, Saturday Night Live. The story is told in relative real time covering the last 90 minutes before its initial 11:30 PM EST debut in 1975. We watch Michaels try and deal with squabbling cast members, striking union members, failing technology, his ex-wife (Rachel Sennot) who also happens to be a primary producer of the show, muppets, and studio bosses that are doubtful whether this project will ever make it to air. I understand in essence why the real-time setting is here to provide more pressure and urgency as Michaels is literally running out of time. The problem is that we know the show will be a success, so inventing doubtful older TV execs to add extra antagonists feels like maybe the framing by itself was lacking. Think about Air but you added a fictional exec whose only purpose was to say, “I don’t think this Michael Jordan guy will ever succeed.” There are interesting conflicts and subplots, especially with the different groups that Michaels has to manage, but when it’s all stuffed in such a tight time frame, rather than making the movie feel more chaotic and anxious, it makes those problems and subplots feel underdeveloped or arbitrary. I would relish a behind-the-scenes movie about SNL history but the best version of that would be season 11, the “lost season,” when Michaels came back to save the show and there were legitimate discussions over whether to cancel the show. Admittedly, we would already know the show survives, but does the public know what happened to people like Terry Sweeney and Danitra Vance? Does the public know what kind of sacrifices Michaels had to make? That’s the SNL movie we deserve. Alas, Saturday Night is an amiable movie with fun actors playing famous faces, but even the cast conflicts have to be consolidated to the confined time frame. This is a clear-cut example where the setting sabotages much of what this SNL movie could have offered for its fans.

With September 5, we remain almost entirely in the control room of ABC Sports as they cover the fateful 1972 Munich Olympics after the Israeli athletes are taken hostage by terrorists. It’s a subject covered in plenty of other movies, including Steven Spielberg’s Munich and the 1999 Oscar-winning documentary One Day in September, but now we’re watching it from the perspective of the journalists thrust into the spotlight to try and cover an important and tragic incident as it plays out by the hour. It’s an interesting perspective and gives voice to several thorny ethical issues, like when the news team is live broadcasting an oncoming police assault, which the terrorists can watch and prepare for as well. The movie is filmed in a suitable docu-drama style and the pacing is as swift as the editing, and that’s ultimately what holds me back from celebrating the movie more. It’s an interesting anecdote about media history, but September 5 fails to feel like a truly insightful addition to the history and understanding of this tragedy. It’s so focused on the people in the studio and restrained to this one day that it doesn’t allow for us to really dwell or develop in the consequences of this day as well as the consequences of their choices on this fateful day. The movie feels like a dramatization of a select batch of interviews from a larger, more informative documentary on the same subject. It’s well-acted and generally well-written, though I challenge people to recall any significant detail of characters besides things like “German translator” and “Jewish guy.” It’s a worthy story but one that made me wish I could get a fuller picture of its impact and meaning. Instead, we get a procedural about a ragtag group of sports journalists thrust into a global political spotlight. There’s just larger things at stake, including the inherent drama of the lives at risk, than if they’ll get the shot.

With September 5, we remain almost entirely in the control room of ABC Sports as they cover the fateful 1972 Munich Olympics after the Israeli athletes are taken hostage by terrorists. It’s a subject covered in plenty of other movies, including Steven Spielberg’s Munich and the 1999 Oscar-winning documentary One Day in September, but now we’re watching it from the perspective of the journalists thrust into the spotlight to try and cover an important and tragic incident as it plays out by the hour. It’s an interesting perspective and gives voice to several thorny ethical issues, like when the news team is live broadcasting an oncoming police assault, which the terrorists can watch and prepare for as well. The movie is filmed in a suitable docu-drama style and the pacing is as swift as the editing, and that’s ultimately what holds me back from celebrating the movie more. It’s an interesting anecdote about media history, but September 5 fails to feel like a truly insightful addition to the history and understanding of this tragedy. It’s so focused on the people in the studio and restrained to this one day that it doesn’t allow for us to really dwell or develop in the consequences of this day as well as the consequences of their choices on this fateful day. The movie feels like a dramatization of a select batch of interviews from a larger, more informative documentary on the same subject. It’s well-acted and generally well-written, though I challenge people to recall any significant detail of characters besides things like “German translator” and “Jewish guy.” It’s a worthy story but one that made me wish I could get a fuller picture of its impact and meaning. Instead, we get a procedural about a ragtag group of sports journalists thrust into a global political spotlight. There’s just larger things at stake, including the inherent drama of the lives at risk, than if they’ll get the shot.

Nate’s Grades:

Saturday Night: C+

September 5: B

Dog Man (2025)

I probably wouldn’t have as much familiarity, and good feelings for the Dog Man series of books had I not become a father to a Dog Man-obsessed kiddo. The silly and imaginative comic books by Dav Pilkey, creator of Captain Underpants, are easy to enjoy with their upbeat tone, sly satire, and whimsical child-like art style. The movie is essentially all that you would want in a Dog Man movie, replaying some of the more famous stories and images and characters from some of the books. Dog Man is born when a police officer and his trusty canine sidekick get into an explosion and have their bodies surgically attached to one another becoming the ultimate crime fighter/man’s best friend. Dog Man has to battle villains like Petey (voiced by Pete Davidson), an evil cat genius, and Flippy (Ricky Gervais), a super intelligent fish with telekinetic powers as well as impress the always harried Chief (Lil Rel Howery). It’s a movie aimed squarely a children without any larger themes beyond life lessons about basic responsibility and empathy, important lessons but ones simplified and aimed at is target audience. The pacing and jokes are swift and the vocal cast is each well suited to the task, with Davidson being an inspired choice for the easily flummoxed and dastardly Petey. The material where Petey makes a child clone of himself and basically learns about parenthood is the best part of the books and could have been explored further in the movie. Still, it’s a low-stakes and goofy movie that mostly succeeds at channeling the appeal of the books. If you’re a Dog Man fan, or the parent to one, then the movie may be everything they wanted, though even at 80 minutes much longer than most bedtime reads.

I probably wouldn’t have as much familiarity, and good feelings for the Dog Man series of books had I not become a father to a Dog Man-obsessed kiddo. The silly and imaginative comic books by Dav Pilkey, creator of Captain Underpants, are easy to enjoy with their upbeat tone, sly satire, and whimsical child-like art style. The movie is essentially all that you would want in a Dog Man movie, replaying some of the more famous stories and images and characters from some of the books. Dog Man is born when a police officer and his trusty canine sidekick get into an explosion and have their bodies surgically attached to one another becoming the ultimate crime fighter/man’s best friend. Dog Man has to battle villains like Petey (voiced by Pete Davidson), an evil cat genius, and Flippy (Ricky Gervais), a super intelligent fish with telekinetic powers as well as impress the always harried Chief (Lil Rel Howery). It’s a movie aimed squarely a children without any larger themes beyond life lessons about basic responsibility and empathy, important lessons but ones simplified and aimed at is target audience. The pacing and jokes are swift and the vocal cast is each well suited to the task, with Davidson being an inspired choice for the easily flummoxed and dastardly Petey. The material where Petey makes a child clone of himself and basically learns about parenthood is the best part of the books and could have been explored further in the movie. Still, it’s a low-stakes and goofy movie that mostly succeeds at channeling the appeal of the books. If you’re a Dog Man fan, or the parent to one, then the movie may be everything they wanted, though even at 80 minutes much longer than most bedtime reads.

Nate’s Grade: B-

A Real Pain (2024)

A funny, poignant, and surprisingly gentle movie about two cousins going on a journey to retrace their family history and honor that legacy while trying to reconcile their privileged connection to that past. Written and directed by Jesse Eisenberg, who also stars as David, a generally normal family man traveling with his much more jubilant and troubled cousin, Benji (Kieran Culkin). They’re on a tour through Poland and visiting infamous Holocaust historical sites, ultimately finding their grandmother’s home she fled so many decades ago. The cousins are dramatically different; David is timid and anxiety-ridden, and Benji is the life of any party, an impulsive yet charming people-person. The tour is meant to draw them closer together, to each other, to their shared historical roots, but it might also make them realize what cannot be reconciled. This is an unassuming little movie about a couple characters chafing and growing through their interactions, getting a better understanding of one another and what makes them tick. It’s really the Benji show, and Culkin is terrific, effortlessly charming and funny but with a real tinge of sadness underlying his garrulous energy. There’s real pain behind the surface of this character that he’s trying so hard to mask, though it appears in fleeting moments of vulnerability. Benji causes the various characters along the tour to think differently about their own situations, their own connections to the past, including his cousin, and ultimately makes the journey feel worthwhile. At a tight 90 minutes, A Real Pain is a small movie about big things, and Eisenberg has a nimble touch as writer/director to make he time spent with strangers feel insightful and rewarding.

A funny, poignant, and surprisingly gentle movie about two cousins going on a journey to retrace their family history and honor that legacy while trying to reconcile their privileged connection to that past. Written and directed by Jesse Eisenberg, who also stars as David, a generally normal family man traveling with his much more jubilant and troubled cousin, Benji (Kieran Culkin). They’re on a tour through Poland and visiting infamous Holocaust historical sites, ultimately finding their grandmother’s home she fled so many decades ago. The cousins are dramatically different; David is timid and anxiety-ridden, and Benji is the life of any party, an impulsive yet charming people-person. The tour is meant to draw them closer together, to each other, to their shared historical roots, but it might also make them realize what cannot be reconciled. This is an unassuming little movie about a couple characters chafing and growing through their interactions, getting a better understanding of one another and what makes them tick. It’s really the Benji show, and Culkin is terrific, effortlessly charming and funny but with a real tinge of sadness underlying his garrulous energy. There’s real pain behind the surface of this character that he’s trying so hard to mask, though it appears in fleeting moments of vulnerability. Benji causes the various characters along the tour to think differently about their own situations, their own connections to the past, including his cousin, and ultimately makes the journey feel worthwhile. At a tight 90 minutes, A Real Pain is a small movie about big things, and Eisenberg has a nimble touch as writer/director to make he time spent with strangers feel insightful and rewarding.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Snack Shack (2024)

The coming-of-age sub-genre is a familiar and well-worn formula, but with the right filmmaker and voice, it can become refreshingly alive once again, like hearing your favorite song covered by an exciting different artist. Snack Shack is an exuberantly charming movie about one summer with 14-year-old best friends who are constantly running money making schemes and hustles. They overbid to run the concession stand at their community pool, but the best buds are entrepreneurial whizzes and turn the snack shack into a smashing success. There’s plenty of familiar genre elements, from bullies, parents they’ll have more appreciation and understanding from at summer’s end, parties and self-discovery, crushes and jealousies that will test their limits of loyalty; there might not be anything new during these 110 minutes, but it’s the nostalgic authenticity and verve from writer/director Adam Carter Rehmeier (Dinner in America) that makes the movie shine. The movie is practically bristling with details that feel so well-realized and genuine. You’ll enjoy spending time in this world and with these characters, reliving the summer of 1991 in Nebraska. Gabriel LaBelle (The Fabelmans) is fantastic as Moose, more the live-wire, always-smiling, charismatic smooth-talker of the two friends. Every second he’s onscreen makes you inch closer to the screen. I don’t think some of the downer plot turns late in the movie feel like a fit and are there to form the Hard Truths experiences meant to shake the innocence of youth. For a movie this jubilant and sunny, it feels like an abrupt tonal swerve that’s more deferential to genre expectations than the previous vibe of the movie. Despite some minor missteps, the good times cannot be thwarted and Snack Shack is a funny and refreshingly retro peon to being young.

The coming-of-age sub-genre is a familiar and well-worn formula, but with the right filmmaker and voice, it can become refreshingly alive once again, like hearing your favorite song covered by an exciting different artist. Snack Shack is an exuberantly charming movie about one summer with 14-year-old best friends who are constantly running money making schemes and hustles. They overbid to run the concession stand at their community pool, but the best buds are entrepreneurial whizzes and turn the snack shack into a smashing success. There’s plenty of familiar genre elements, from bullies, parents they’ll have more appreciation and understanding from at summer’s end, parties and self-discovery, crushes and jealousies that will test their limits of loyalty; there might not be anything new during these 110 minutes, but it’s the nostalgic authenticity and verve from writer/director Adam Carter Rehmeier (Dinner in America) that makes the movie shine. The movie is practically bristling with details that feel so well-realized and genuine. You’ll enjoy spending time in this world and with these characters, reliving the summer of 1991 in Nebraska. Gabriel LaBelle (The Fabelmans) is fantastic as Moose, more the live-wire, always-smiling, charismatic smooth-talker of the two friends. Every second he’s onscreen makes you inch closer to the screen. I don’t think some of the downer plot turns late in the movie feel like a fit and are there to form the Hard Truths experiences meant to shake the innocence of youth. For a movie this jubilant and sunny, it feels like an abrupt tonal swerve that’s more deferential to genre expectations than the previous vibe of the movie. Despite some minor missteps, the good times cannot be thwarted and Snack Shack is a funny and refreshingly retro peon to being young.

Nate’s Grade: B+

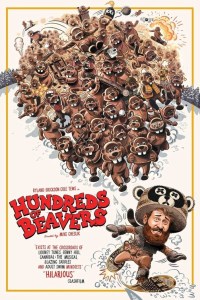

Hundreds of Beavers (2024)

It’s become a cliche for film critics to say, “you’ve never seen a movie like this,” and that’s only partially true with the DIY indie comedy sensation, Hundreds of Beavers. You may have seen this before though decades ago in classic Looney Tunes cartoons, a clear inspiration for the inventive visual slapstick and antic comedy imagination on full display. The commitment of the cast and crew to make a modern-day Looney Tunes is so rare and the results so amazingly executed that when I questioned whether we needed a full movie of this rather than a short film, I cast aside the question and chose to simply enjoy the fullness of the movie. Why scrimp on imagination and ingenuity and divine wackiness for only fifteen minutes when we can have one hundred? If you’re a fan of inspired slapstick comedy, and especially the Golden Era of classic cartoons (1944-1964), then Hundreds of Beavers will be a celebratory experience that could boast hundreds of laughs.

It’s become a cliche for film critics to say, “you’ve never seen a movie like this,” and that’s only partially true with the DIY indie comedy sensation, Hundreds of Beavers. You may have seen this before though decades ago in classic Looney Tunes cartoons, a clear inspiration for the inventive visual slapstick and antic comedy imagination on full display. The commitment of the cast and crew to make a modern-day Looney Tunes is so rare and the results so amazingly executed that when I questioned whether we needed a full movie of this rather than a short film, I cast aside the question and chose to simply enjoy the fullness of the movie. Why scrimp on imagination and ingenuity and divine wackiness for only fifteen minutes when we can have one hundred? If you’re a fan of inspired slapstick comedy, and especially the Golden Era of classic cartoons (1944-1964), then Hundreds of Beavers will be a celebratory experience that could boast hundreds of laughs.

Set amid the early 1800s in the Wisconsin winter, Jean Kayak (Ryland Brickson Cole Tews) is a frontiersman trying to make a name for himself. He wants to be the best fur trapper in the land, and if he nets enough furs, he’ll be granted the chance to marry the pretty daughter (Olivia Graves) of the local Merchant (Doug Mancheski). And with that, the rest of the movie is watching Jean try to outsmart the wildlife (portrayed as people in giant mascot costumes) and collect enough pelts.

By the nature of its premise and intention, this is not going to be a movie for everyone, or even many, but if it’s for you, it will feel like comedy manna from heaven. The grand appeal of Hundreds of Beavers is the sheer surprise of it all, with the jokes coming fast. The pacing of this movie is at spoof-movie levels, with jokes hitting in weaves and often, complete setups and punchlines taken care of in under ten seconds. The joke-per-second ratio of this movie is off the charts, especially when the movie also begins building its own internal logic and foundation for running gags. That creates an even deeper and richer tableau for comedy, with jokes piling on top of one another and building escalations and extensions. I’m genuinely amazed at the creativity on display in every minute of this movie. The fantastical imagination of this movie could power an entire Hollywood studio slate of movies. I was in sheer awe of how many different joke scenarios it could devise with this scant premise, and I was happily surprised, no, elated, when the filmmakers kept this level of silliness and invention going until the very end of the movie. I was chuckling and guffawing throughout, and I strongly feel like this is the kind of movie that, if you watch it with a group of like-minded friends, can produce peals of infectious laughter.

By the nature of its premise and intention, this is not going to be a movie for everyone, or even many, but if it’s for you, it will feel like comedy manna from heaven. The grand appeal of Hundreds of Beavers is the sheer surprise of it all, with the jokes coming fast. The pacing of this movie is at spoof-movie levels, with jokes hitting in weaves and often, complete setups and punchlines taken care of in under ten seconds. The joke-per-second ratio of this movie is off the charts, especially when the movie also begins building its own internal logic and foundation for running gags. That creates an even deeper and richer tableau for comedy, with jokes piling on top of one another and building escalations and extensions. I’m genuinely amazed at the creativity on display in every minute of this movie. The fantastical imagination of this movie could power an entire Hollywood studio slate of movies. I was in sheer awe of how many different joke scenarios it could devise with this scant premise, and I was happily surprised, no, elated, when the filmmakers kept this level of silliness and invention going until the very end of the movie. I was chuckling and guffawing throughout, and I strongly feel like this is the kind of movie that, if you watch it with a group of like-minded friends, can produce peals of infectious laughter.

I really want to celebrate just how whimsically silly this movie can be, with humor that ranges from clever to stupid to stupidly clever. Much of the humor resides around the death and mutilation of animals, which isn’t surprising considering our hero’s goal is to gain hundreds of pelts. It never stops being funny seeing people dressed in giant animal mascot costumes to represent the wildlife, and when they’re killed through the assortment of different means and accidents, the movie adopts classic cartoon visual communication and logic by giving them large X’s covering their eyes. Even when the creatures are losing heads and limbs and getting impaled or giant holes blown through them, the lightness of approach keeps the violence from feeling upsetting or realistic. It’s all just so silly, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not sneaky-smart from a comedy standpoint. There’s one scene where Jean is riding a log down a flume inside a giant wood-harvesting plant the beavers have constructed. A rival log with angry beavers chases him in parallel, and it looks like they’re just about to jump onto his log and grab him. However, they jump but seemingly stay in place, and that’s where the movie cuts to a different shot from a wide angle, to reveal that there are four or five of these flumes running parallel and not merely two. The joke itself is only a few careful seconds, like most of the jokes in Hundreds of Beavers, but it demonstrates the level of thought and ingenuity in the comedy construction, and that’s even before spaceships and beaver kaiju.

The acting is fully committed to the exaggerated and cartoonish tone of the proceedings. These actors are selling the jokes tremendously well, and since the movie is practically wordless, most of it comes from physicality and expression. It hearkens back to the early silent era of moviemaking by the likes of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplain making millions laugh. Even the smallest roles are filled with committed actors helping to make the jokes even funnier. The people in those mascot costumes can be riotous simply in how they slump their body, cock their head, choose their pauses and gesticulations. Watching the movie is a reminder at how universal comedy can be when you have the right people who understand the fundamentals of finding the funny. Tews, also serving as co-writer with director Mike Cheslike (L.I.P.S., The Get Down), is our human face for much of the mayhem, and he can play bedeviled and befuddled with flair. His facial expressions and exaggerations are a consistent key to framing and anchoring the tone of every moment.

The acting is fully committed to the exaggerated and cartoonish tone of the proceedings. These actors are selling the jokes tremendously well, and since the movie is practically wordless, most of it comes from physicality and expression. It hearkens back to the early silent era of moviemaking by the likes of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplain making millions laugh. Even the smallest roles are filled with committed actors helping to make the jokes even funnier. The people in those mascot costumes can be riotous simply in how they slump their body, cock their head, choose their pauses and gesticulations. Watching the movie is a reminder at how universal comedy can be when you have the right people who understand the fundamentals of finding the funny. Tews, also serving as co-writer with director Mike Cheslike (L.I.P.S., The Get Down), is our human face for much of the mayhem, and he can play bedeviled and befuddled with flair. His facial expressions and exaggerations are a consistent key to framing and anchoring the tone of every moment.

While the budget is a relatively modest $150,000, it doesn’t mean the movie looks pedestrian. Choosing to film in black and white helps mask some possible limitations, and the creative choice to go with people in giant mascot costumes helps too, but much of the movie is elevated by its clever green screen effects work. Whether it’s augmenting the snowy outdoor wilderness with exaggerated elements, like traps and contraptions and holes in ice, or segments filmed entirely on green screen and utilizing heavy composites to magnify the number of animals on screen, it all better fulfills the vision and tone. The finale inside the beaver complex is a wild sequence reminiscent of Marvin the Martian landscapes and interior design. The look of the movie, while rough around the edges at points, leans into its lo-fi aesthetics to make it part of its charm, much like the goofy mascot costumes. The continued goofiness doesn’t cancel out the visual audaciousness, even when that audacity is in the guise of creating something so stupid for words.

I would advise anyone to give Hundreds of Beavers a try, even if for only ten minutes. If you don’t connect with the film’s comedic wavelength or appreciate the ingenuity of the players, then so be it. But I think more than enough will be charmed and impressed by its energy and creativity. I said before that there was once or twice, during the first half, that I questioned whether we needed a feature-length version of this kind of movie. Then it occurred to me how rare such a movie like this is, how singular its vision can be, and how instead of questioning its duration, I then chose to celebrate its cheerful existence, and every new joke was a new opportunity to produce smiles and laughter, and I anxiously waited for the next and the next, my smile only broadening. Hundreds of Beavers is one of the craziest movies you will see but it’s also, at its core, a celebration of comedy and collaboration and the special appeal of moviemaking and those with a passion for being silly. In these trying times of uncertainty, I’ll take a feature-length dose of that, please and thank you.

I would advise anyone to give Hundreds of Beavers a try, even if for only ten minutes. If you don’t connect with the film’s comedic wavelength or appreciate the ingenuity of the players, then so be it. But I think more than enough will be charmed and impressed by its energy and creativity. I said before that there was once or twice, during the first half, that I questioned whether we needed a feature-length version of this kind of movie. Then it occurred to me how rare such a movie like this is, how singular its vision can be, and how instead of questioning its duration, I then chose to celebrate its cheerful existence, and every new joke was a new opportunity to produce smiles and laughter, and I anxiously waited for the next and the next, my smile only broadening. Hundreds of Beavers is one of the craziest movies you will see but it’s also, at its core, a celebration of comedy and collaboration and the special appeal of moviemaking and those with a passion for being silly. In these trying times of uncertainty, I’ll take a feature-length dose of that, please and thank you.

Nate’s Grade: A

Anora (2024)

The critically-anointed Anora is the indie of the year, winning top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the first for an English-speaking movie in over a dozen years, and poised to be a major awards player down the stretch, some might even say front-runner for top prizes. It starts like a deconstruction of Pretty Woman, with Mikey Madison (Scream 5) playing Anora, a stripper who recognizes the advantageous possibilities flirting with a young rich Russian scion, Vanya. He wants her to be his girlfriend, and over a sex-fueled week, he’s so smitten that he wants to make Anora his wife. This whirlwind relationship hits the wall, however, once Vanya’s family inserts themself into his life, determined to annul the hasty marriage at all costs.

The critically-anointed Anora is the indie of the year, winning top prize at the Cannes Film Festival, the first for an English-speaking movie in over a dozen years, and poised to be a major awards player down the stretch, some might even say front-runner for top prizes. It starts like a deconstruction of Pretty Woman, with Mikey Madison (Scream 5) playing Anora, a stripper who recognizes the advantageous possibilities flirting with a young rich Russian scion, Vanya. He wants her to be his girlfriend, and over a sex-fueled week, he’s so smitten that he wants to make Anora his wife. This whirlwind relationship hits the wall, however, once Vanya’s family inserts themself into his life, determined to annul the hasty marriage at all costs.

The movie becomes infinitely better at the hour mark when the exasperated extended Russian family comes into the picture. You worry they might be menacing, as they don’t want this stranger with access to the family wealth, but they’re far more bumbling, and Anora transforms into an unexpected comedy. It certainly wasn’t an authentic romance. Clearly Vanya was a meal ticket more than a three-dimensional romantic interest. The kid is an immature, annoying dolt, so we know Anora isn’t legitimately falling in love with him. The scenes of them building a “relationship” could have been cut in half because we already understood the nature of the two of them using one another. The last hour makes for a greatly entertaining turn of events as the unlikely and bickering posse searches New York City for a runaway Vanya. The movie feels propulsive and chaotic and blissfully alive. Ultimately, I don’t know what it all adds up to. Anora isn’t really a sharply drawn character, but none of the characters are particularly well developed. The pseudo-romantic fantasy of its premise, becoming a “princess” of luxury, isn’t really deconstructed with precision. It’s an unexpectedly funny ensemble comedy at its best, but I’m left indifferent to what other value I can take away. It’s well-acted and surprising, but it’s a vacuous side excursion made into a full movie that somehow has bewitched movie critics into seeing more. Perhaps they too have become overly smitten with Anora’s surface-level charms.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Harold and the Purple Crayon (2024)

As an elder Millennial, I’ll try and ignore my rising bile for what they did to my boy Harold here, and I’ll simply ask who was this movie for? The big screen adaptation of the classic 1955 children’s book by Crockett Johnson that celebrates the power of imagination is a mishmash of mawkish feel-good family nonsense, fantasy power wish-fulfillment, and grating fish-out-of-water comedic antics. Increasingly missable actor Zachery Levi (Shazam!) plays yet another glorified man-baby, this time as an “adult” Harold who ventures into the Real World to search for his narrator, essentially the god of his purple-hued universe. He befriends a lonely boy with a big imagination and the kid’s single mom (poor Zooey Desceanel) and life lessons are learned while “adult” Harold makes a mess of just about everything as he leaves behind chaos and disaster. Eventually Harold has a full-on wizard duel against a villainous librarian and wannabe published fantasy author played by Jermaine Clement. That’s right, Harold and the Purple Crayon transforms into a magic battle over the fate of the all-powerful ring, I mean crayon. Making matters worse is Levi’s hyperactive schtick that has been growing stale for years and is tiresome and annoying throughout the movie. It’s also quite ironic, and phony, that a movie expressly proclaiming the power of individuality and imagination is so thoroughly and depressingly generic. This should have been animated or left alone, period.

As an elder Millennial, I’ll try and ignore my rising bile for what they did to my boy Harold here, and I’ll simply ask who was this movie for? The big screen adaptation of the classic 1955 children’s book by Crockett Johnson that celebrates the power of imagination is a mishmash of mawkish feel-good family nonsense, fantasy power wish-fulfillment, and grating fish-out-of-water comedic antics. Increasingly missable actor Zachery Levi (Shazam!) plays yet another glorified man-baby, this time as an “adult” Harold who ventures into the Real World to search for his narrator, essentially the god of his purple-hued universe. He befriends a lonely boy with a big imagination and the kid’s single mom (poor Zooey Desceanel) and life lessons are learned while “adult” Harold makes a mess of just about everything as he leaves behind chaos and disaster. Eventually Harold has a full-on wizard duel against a villainous librarian and wannabe published fantasy author played by Jermaine Clement. That’s right, Harold and the Purple Crayon transforms into a magic battle over the fate of the all-powerful ring, I mean crayon. Making matters worse is Levi’s hyperactive schtick that has been growing stale for years and is tiresome and annoying throughout the movie. It’s also quite ironic, and phony, that a movie expressly proclaiming the power of individuality and imagination is so thoroughly and depressingly generic. This should have been animated or left alone, period.

Nate’s Grade: D+

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (2024)

Usually sequels over thirty years later reek of desperation, trying to rekindle the past while usually only hoping to tickle people’s fading sense of nostalgia. Rare is the 30-year-plus sequel that excels by breaking free of its imitator and making us see the original in a new light. It helps to keep your expectations in check, especially for a project that is so miraculous as the original 1988 Beetlejuice. What a wild movie that was, an introduction to horror comedy for a generation, and a near-perfect balance of creepy, silly, and imaginative. From director Tim Burton’s career-launching sense of style, to Michael Keaton’s electric comedic performance, to Danny Elfman’s outstanding score, to the stop-motion visuals, fun and freaky makeup effects, and you had a madcap movie that felt like a unique discovery. Recreating that is near impossible, but if Beetlejuice Beetlejuice can recreate some of the elements and feelings that made the original what it was, then it can be considered a modestly successful late-stage sequel.

Usually sequels over thirty years later reek of desperation, trying to rekindle the past while usually only hoping to tickle people’s fading sense of nostalgia. Rare is the 30-year-plus sequel that excels by breaking free of its imitator and making us see the original in a new light. It helps to keep your expectations in check, especially for a project that is so miraculous as the original 1988 Beetlejuice. What a wild movie that was, an introduction to horror comedy for a generation, and a near-perfect balance of creepy, silly, and imaginative. From director Tim Burton’s career-launching sense of style, to Michael Keaton’s electric comedic performance, to Danny Elfman’s outstanding score, to the stop-motion visuals, fun and freaky makeup effects, and you had a madcap movie that felt like a unique discovery. Recreating that is near impossible, but if Beetlejuice Beetlejuice can recreate some of the elements and feelings that made the original what it was, then it can be considered a modestly successful late-stage sequel.

Lyrdia Deetz (Wynona Ryder) has become a long-running host of a paranormal TV talk show connecting people with messages from loved ones from beyond the grave. Her teenage daughter, Astrid (Jenna Ortega), is moody and embarrassed by her mother, feeling that she “sold out.” Mother and daughter return back to Connecticut to attend the funeral of Charles Deetz, Lyrdia’s father. Her pretentious and snippy stepmother, Delia (Catherine O’Hara), is trying to better commune with his spirit, and the entire town has become famous for its spooky seasonal history. Meanwhile, Beetlejuice (Keaton) is trying to avoid his former wife, Delores (Monica Bellucci), who naturally is seeking to obliterate him to ectoplasm. He’s still got his sights set on Lydia, who spurned his marriage hopes, and might be able to manipulate the Deetz family back into his control.

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice gets the closest to rekindling that lightning-in-a-bottle alchemy from the 1988 original, serving as an appealing and enjoyable sequel. Nothing will ever be as original and wild and such a discovery as that first movie, which serves as a point of entry for many a Millennial fan who discovered that irresistible Tim Burton Neo-Gothic aesthetic. However, it recreates enough of the qualities that stood out about the original. The skewed sense of humor and surreal visuals, as well as goofy slapstick and vibrant imagination about life after death, it’s all such a fertile playground for Burton’s visual charms. The genius of the original was telling a ghost story from the ghost perspective as they learned about how to be better ghosts to try and scare their new living owners away. Given the world of the dead, there’s such tremendous storytelling and world-building possibilities here, explored richly in the animated 90s series for kids. Further stories in this universe have an automatically appealing power, and it’s just nice to watch Burton apply his specific aesthetic again, something fans haven’t really seen since 2007’s Sweeney Todd. I appreciated the weird morbid details and the practical production values; the Alice in Wonderland movies have shown that the “Burton look” isn’t best complimented by massive green screen sets. Having Burton, the “Burton look,” the original actors, with some exceptions (more on that later), and enough of that offbeat, chaotic, morbid tone return is a victory.

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice gets the closest to rekindling that lightning-in-a-bottle alchemy from the 1988 original, serving as an appealing and enjoyable sequel. Nothing will ever be as original and wild and such a discovery as that first movie, which serves as a point of entry for many a Millennial fan who discovered that irresistible Tim Burton Neo-Gothic aesthetic. However, it recreates enough of the qualities that stood out about the original. The skewed sense of humor and surreal visuals, as well as goofy slapstick and vibrant imagination about life after death, it’s all such a fertile playground for Burton’s visual charms. The genius of the original was telling a ghost story from the ghost perspective as they learned about how to be better ghosts to try and scare their new living owners away. Given the world of the dead, there’s such tremendous storytelling and world-building possibilities here, explored richly in the animated 90s series for kids. Further stories in this universe have an automatically appealing power, and it’s just nice to watch Burton apply his specific aesthetic again, something fans haven’t really seen since 2007’s Sweeney Todd. I appreciated the weird morbid details and the practical production values; the Alice in Wonderland movies have shown that the “Burton look” isn’t best complimented by massive green screen sets. Having Burton, the “Burton look,” the original actors, with some exceptions (more on that later), and enough of that offbeat, chaotic, morbid tone return is a victory.

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice doesn’t so much alter our understanding of the world of the dead as established; it doesn’t radically rethink the landscape but it doesn’t repeat the same plot events either. I really liked the evolution of the adult Lydia as a jaded TV host. There’s a real dramatic punch to the reality that she sees the dead but has yet to see her deceased husband. She is incapable of reuniting with the man she misses the most, and she doesn’t know why. That yearning, paired with a lingering thematic mystery, can be a palpable storyline to explore. Pair that with some three generations of Deetz women trying to understand one another and work through personal resentments and we have fertile narrative ground. The three women were my favorite part of the movie, and their interactions and reflections on parenting and the challenges of trying to better understand one another are the foundation of the movie’s sense of heart. I really enjoyed the dynamic between the three, significantly upping Delia’s screen time and finding room to give her more dimension, an artist struggling in the wake of her grief. I’m a bit surprised that Ortega’s character isn’t more central to the drama. For all intents and purposes, she’s Lydia 2.0, so butting heads with Lydia 1.0 I guess feels redundant, so the story sends her off to find a cute boy in town and use that as an excuse for several unexpected needle-drop song use. There’s something inherently wrong watching a Tim Burton movie and hearing contemporary music. Imagine the Beetlejuice “Day-O” singalong but to, say, Sabrina Carpenter instead. No.

Beetlejuice, as a character, is such an exciting agent of chaos, a horny ghost who operates on the same tonal wavelength as a Looney Tunes cartoon character. Even though the original movie is named after the guy, he’s only in the film for approximately twenty percent. Keaton was absolutely incredible in his comedic bravado, creating much of the character through his ad-libs and hair and makeup choices. Keaton is still fantastic in this go-for-broke sort of performance, a performance we’ve seen far less as he’s settled into a respectable dramatic acting career. It’s hard to remember, dear reader, but when Keaton was initially cast for Burton’s Batman, the fan base at the time was up in arms, considering Keaton more of an un-serious funnyman. It would have been easy to have Beetlejuice front and center for the movie, so it’s admirable that Burton and Keaton decided to keep his on-screen appearances short, leaving people wanting more. There’s a late turn of events that pairs Lydia and Beetlejuice together, and I wish this fractious pairing had been the bulk of the movie. The whole enemies-to-uneasy-allies would have put much more emphasis on their character dynamic and the comic combustibility. Still, seeing these characters come back and retain their appeal and personality without obnoxious pandering is welcomed.

Beetlejuice, as a character, is such an exciting agent of chaos, a horny ghost who operates on the same tonal wavelength as a Looney Tunes cartoon character. Even though the original movie is named after the guy, he’s only in the film for approximately twenty percent. Keaton was absolutely incredible in his comedic bravado, creating much of the character through his ad-libs and hair and makeup choices. Keaton is still fantastic in this go-for-broke sort of performance, a performance we’ve seen far less as he’s settled into a respectable dramatic acting career. It’s hard to remember, dear reader, but when Keaton was initially cast for Burton’s Batman, the fan base at the time was up in arms, considering Keaton more of an un-serious funnyman. It would have been easy to have Beetlejuice front and center for the movie, so it’s admirable that Burton and Keaton decided to keep his on-screen appearances short, leaving people wanting more. There’s a late turn of events that pairs Lydia and Beetlejuice together, and I wish this fractious pairing had been the bulk of the movie. The whole enemies-to-uneasy-allies would have put much more emphasis on their character dynamic and the comic combustibility. Still, seeing these characters come back and retain their appeal and personality without obnoxious pandering is welcomed.

The screenwriters find a clever solution for the Jeffrey Jones Dilemma. For those unaware, Jones, who portrayed Lydia’s father in the original, and best known for pugnacious supporting roles in movies like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Howard the Duck, and HBO’s Deadwood, was charged with soliciting a child for sexual exploitation. The movie continues with the character of Charles Deetz but without the involvement of Jones. The character gets his top eaten by a shark, so for the rest of the movie he’s a walking half of a corpse with a mumbly voice. It’s a clever way to include the character without the need for the actor.

With that decision to limit the Beetlejuice quotient of Beetlejuice Beetlejuice, it makes for a sloppier movie juggling a few underwritten subplots and side characters. The biggest non-factor is the return of Mrs. Beetlejuice. Here is a powerful antagonist who has the literal ability to suck out the souls of the recently dead and turn them into shriveled husks. She’s seeking vengeance against her ex and tracking him down through the netherworld. And yet, she could be completely eliminated from the movie without really affecting the other storylines. The whole Mrs. Beetlejuice/vengeful ex-wife character feels like a holdover from a different sequel script, clumsily grafted onto this other project, a vestigial artifact of another path not taken. There’s plenty of potential with the concept of the past victims of Beetlejuice coming back to seek retribution, and especially a trail of angry former lovers. It would explore the character’s history more meaningfully than an albeit amusing silent film interlude about how he married her during the era of the Bubonic Plague. We see how he died as a human, but there’s hundreds of years that can be illuminated from his failed schemes and odd jobs. Certainly there could be a whole club of ax-grinding malcontents sharing their mutual hatred of the Ghost with the Most. This character should better reflect Beetlejuice, and instead she’s just a monster on the prowl that eventually gets indifferently cast aside. It feels like Burton was looking for something for Bellucci to portray (Burton and Bellucci have officially been dating since 2023).

She’s not alone as an antagonistic villain that pops up to provide momentary danger but is also hastily resolved to the point that it raises the question why they were even involved. There are three antagonists, not counting Beetlejuice, that appear throughout to threaten our Deetz family members in Act Three, each of them individually interesting and targeting a different member of the family for ill-gotten gain. Yet each one of these characters is conquered so easily that it nullifies their importance and overall threat. If Beetlejuice could, at any moment, just open a trapdoor to hellfire at a moment’s notice, what danger does any other character pose then? If a sand worm can just appear from nowhere and consume our pesky antagonist, then why can’t this be a convenient solution earlier? The defeats feel arbitrary, which make the antagonists feel arbitrary, which is disappointing considering that we have the full supernatural arsenal of undead possibilities to tap into. I enjoyed these characters for the most part, but it’s hard not to feel like they’re tacked-on and underwritten. The same can be said about Willem Dafoe’s police chief, a former actor who played a chief on TV and now tries to fill the role for real after death. I’m always glad to have more Dafoe in my movies (woefully underrepresented in rom-coms, you cowards!) but he’s just mugging in the corner, waiting for some greater significance or, at minimum, more memorably morbid oddity to perform.

She’s not alone as an antagonistic villain that pops up to provide momentary danger but is also hastily resolved to the point that it raises the question why they were even involved. There are three antagonists, not counting Beetlejuice, that appear throughout to threaten our Deetz family members in Act Three, each of them individually interesting and targeting a different member of the family for ill-gotten gain. Yet each one of these characters is conquered so easily that it nullifies their importance and overall threat. If Beetlejuice could, at any moment, just open a trapdoor to hellfire at a moment’s notice, what danger does any other character pose then? If a sand worm can just appear from nowhere and consume our pesky antagonist, then why can’t this be a convenient solution earlier? The defeats feel arbitrary, which make the antagonists feel arbitrary, which is disappointing considering that we have the full supernatural arsenal of undead possibilities to tap into. I enjoyed these characters for the most part, but it’s hard not to feel like they’re tacked-on and underwritten. The same can be said about Willem Dafoe’s police chief, a former actor who played a chief on TV and now tries to fill the role for real after death. I’m always glad to have more Dafoe in my movies (woefully underrepresented in rom-coms, you cowards!) but he’s just mugging in the corner, waiting for some greater significance or, at minimum, more memorably morbid oddity to perform.

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is better than a desperate sequel cash-grab, though there are elements, ideas, characters, and jokes that could have been smoothed out, better incorporated, and developed to maximize the potential of the undead setting. It’s an enjoyable throwback for the fans of the original that does manage to tap into enough of those potent elements that made the original so memorable. It’s definitely less edgy and transgressive, maybe even a little too safe given the territory of spooky specters; the entire Soul Train bit felt like a bad Saturday Night Live sketch from the 1980. However, it’s still got enough of the charm and silliness to leave fans, old and new, smiling and wondering where it might go next in its wild world.

Nate’s Grade: B

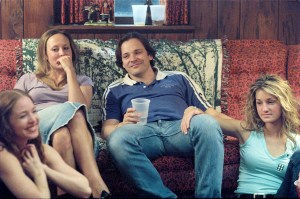

Garden State (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

Andrew Large Largeman (Braff) is an out-of-work actor living in an anti-depressant haze in LA. He heads back to his old stomping grounds in New Jersey when he learns that his mother has recently died. Andrew has to reface his psychiatrist father (Ian Holm), the source of his guilt and prescribed numbness. He has forgotten his lithium for his trip, and the consequences allow Andrew to begin to awaken as a human being once more. He meets old friends, including Mark (Peter Sarsgaard), who now digs graves for a living and robs them when he can. He parties at the mansion of a friend made rich by the invention of silent Velcro. Things really get moving when Andrew meets Sam (Natalie Portman), a free spirit who has trouble telling the truth and staying still. Their budding relationship coalesces with Andrews re-connection to friends, family, and the joys life can offer.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff deserves a medal for finally coaxing out the actress in Portman. She herself has looked like an overly medicated, numb being in several of her recent films (Star Wars prequels, I’m looking in your direction), but with her plucky, whimsical role in Garden State, Portman proves that her careers acting apex wasn’t in 1994’s The Professional when she was 12. Her winsome performance gives Garden State its spark, and the sincere romance between Sam and Andrew gives it its heart.

Sarsgaard is fast becoming one of the best young character actors out there. After solid efforts in Boys Don’t Cry and Shattered Glass, he shines as a coarse but affectionate grave robber that serves as Andrew’s motivational elbow-in-the-ribs. Only the great Holm seems to disappoint with a rare stilted and vacant performance. This can be mostly blamed on Braff’s underdevelopment of the father role. Even Method Man pops up in a very amusing cameo.

The humor in Garden State truly blossoms. There are several outrageous moments and wonderfully peculiar characters, but their interaction and friction are what provide the biggest laughs. So while Braff may shoehorn in a frisky seeing-eye canine, a knight of the breakfast table, and a keeper of an ark, the audience gets its real chuckles from the characters and not the bizarre scenarios. Garden State has several wonderfully hilarious moments, and its sharp sense of humor directly attributes to its high entertainment value. The film also has some insightful looks at family life, guilt, romance, human connection, and acceptance. Garden State can cut close like a surgeon but it’s the surprisingly elegant tenderness that will resonate most with a crowd.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Garden State is not a flawless first entry for Braff. It really is more a string of amusing anecdotes than an actual plot. The film’s aloof charm seems to be intended to cover over the cracks in its narrative. Braff’s film never ceases to be amusing, and it does have a warm likeability to it; nevertheless, it also loses some of its visual and emotional insights by the second half. Braff spends too much time on less essential moments, like the all-day trip by Mark that ends in a heavy-handed metaphor with an abyss. The emotional confrontation between father and son feels more like a baby step than a climax. Braff’s characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.

Garden State is a movie thats richly comic, sweetly post-adolescent, and defiantly different. Braff reveals himself to be a talent both behind the camera and in front of it, and possesses an every-man quality of humility, observation, and warmth that could soon shoot him to Hollywood’s A-list. His film will speak to many, and its message about experiencing lifes pleasures and pains, as long as you are experiencing life, is uplifting enough that you may leave the theater floating on air. Garden State is a breezy, heartwarming look at New York’s armpit and the spirited inhabitants that call it home. Braff delivers a blast of fresh air during the summer blahs.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

In the summer of 2024, there were two indie movies that defined the next years of your existence. If you were under 18, it was Napoleon Dynamite. If you were between 18 and 30, it was Garden State. Zack Braff’s debut as writer/director became a Millennial staple on DVD shelves, and I think at one time it might have been the law that everyone had to own the popular Grammy-winning soundtrack. It wasn’t just an indie hit, earning $35 million on a minimal budget of $2.5 million; it was a Real Big Deal, with big-hearted young people finding solace in its tale of self-discovery and shaking loose from jaded emotional malaise. If you had to determine a list of the most vital Millennial films, not necessarily on quality but on popularity and connection to the zeitgeist, then Garden State must be included. Twenty years later, it’s another artifact of its time, hard to fully square outside of that influential period. It’s a coming-of-age tale wrapped up in about every quirky indie trope of its era, including a chief example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, even though that term was first coined from the AV Club review of 2005’s Elizabethtown. Twenty years later, Garden State still has some warm fuzzies but loses its feels.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Natalie Portman had been an actress that I was more cool over until 2004 with the double-whammy of Garden State and her Oscar-nominated turn in Closer. She’s since become one of the most exciting actors who goes for broke in her performances whether they might work or not. In 2004, I thought her performance in Garden State was an awakening for her, and in 2024 it now feels so starkly pastiche. Bless her heart, but Portman is just calibrated for the wrong kind of movie. Her energy level is two to three times that of the rest of the movie, and while you can say she’s the spark plug of the film, the jolt meant to shake Andrew awake, her character comes across more as an overwritten cry for help. Sam is even more prototypical Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) than Kirsten Dunst’s bouncy character in Elizabethtown. Her entire existence is meant to provoke change upon our male character. This in itself is not an unreasonable fault; many characters in numerous stories are meant to represent a character’s emotional state. It’s just that there isn’t much to Sam besides a grab-bag of quirky characteristics: she’s a compulsive liar, though nothing is ever really done with this being a challenge to building lasting bonds; she’s incapable of keeping pets alive, and Andrew could be just another pet; she’s consumed with being unique to the point of having to stand up and blurt out nonsense words to convince herself that nobody in human history has duplicated her recent combination of sounds and body gestures, but she’s all archetype. She exists to push Andrew along on his reawakening, including introducing him and us to The Shins (“This song will change your life”). She’s entertaining, and Portman is charming, but it’s an example of trying so hard. I thought her cheeks must have hurt from holding a smile so long. I’m sure Braff would compare Sam to Annie Hall, as Diane Keaton was perhaps the mold for the MPDG, except she more than stood on her own and didn’t need a nebbish man to complete her.

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

Admittedly, that soundtrack is still a banger. It soars when it needs to, like Imogen Heep’s “Let Go” over the race-back-to-the-girl finale, and it’s deftly somber when it needs to, like Iron and Wine’s cover of “Such Great Heights” and “The Only Living Boy in New York” paired with our big movie kiss. It’s such a cohesive, thematic whole that lathers over the exposed seams of the movie’s scenic hodgepodge. Braff tried to find similar magic with his musical choices for 2006’s The Last Kiss, a movie he starred in but did not direct (he also provided un-credited rewrites to Paul Haggis’ adapted screenplay). That soundtrack is likewise packed with eclectic artists (he even snags Aimee Mann) but failed to resonate like Garden State. It’s probably because nobody saw the movie and Braff’s character was, as I described in my 2006 review, an overgrown man-child afraid his life lacks “surprises” now that he was going to be a father. Sheesh.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Re-View Grade: C+

Inside Out 2 (2024)

Of all the Pixar hits, 2015’s Inside Out is one of the better movies to develop a sequel for, and thankfully Inside Out 2 is a solid extension from the original. The internal world of Riley’s burgeoning sense of self is so deeply imaginative and creatively rewarding, balancing slapstick and broad humor with a deeper examination of abstract concepts and human psychology (Freud would have loved this movie… or hated it… or just thought about his mother). The unique setting was made so accessible by the nimble screenplay that the viewer was able to learn the rules of this setting and how interconnected the various parts are. While not being as marvelously inventive as its predecessor, nor as poignant (R.I.P. Bing Bong), Inside Out 2 is a heartwarming and reaffirming animated movie that will work for all ages.

Riley is now turning thirteen years old and in the midst of puberty. That means new emotions, and Joy (voiced by Amy Poehler) has to learn to work well with her co-workers, such as Envy, Embarassment, and Ennui. The biggest new addition is Anxiety (voiced by Maya Hawke) who wants to prepare Riley for her life ahead, which seems especially rocky now that Riley knows her two best friends will be going to a different school. A weekend trip to hockey camp becomes Riley’s opportunity to test drive the “new Riley,” the one who impresses the cool older kids and gains their acceptance. This will force Riley to have to determine which set of friends to prioritize, the new or the old, and whether the goofy, kind version can survive to middle school or needs to be snuffed out.

With the sequel, there aren’t any dramatically new wrinkles to the world building already established. We don’t exactly discover any new portions of Riley’s mind, instead choosing to place most of the plot’s emphasis on another long journey back to home base. This time the other core emotions get to stick around with Joy, each of them proving useful during a key moment on the adventure. The externalization of the emotions invites the viewer to feel something toward feelings themselves. When Joy, at her lowest, laments that maybe a hard realization about growing up is that life will simply have less joy, it really hit me. Part of it was just the sad contemplation that accepting adulthood means accepting a life with less happiness, but a big part was teaching this concept to children and being unable to provide them the joy they deserve. Since the 2015 original, my life has gone through different changes and now I watch these movies not just as an individual viewer recalling life as a former adolescent figuring things out, but now I also come from the perspective of a parent with young children, including one turning thirteen. The development of the mind of this little growing person is a heavy responsibility given to people who are, hopefully, up to that very herculean task. We can all try our best, but recognizing limitations is also key. The kids have to have the freedom to be themselves and not pint-sized facsimiles of a parent.

The emotions inside Riley’s mind are featured like internal surrogate parents, tending to the development of Riley’s emotions, morals, and personality. They presumably want what’s best for her, there just happen to be opposing interpretations of what that exactly means, which leads to the majority of conflict with Anxiety. However, there’s also an understanding that Riley has to do things on her own and be able to make mistakes and learn from them. Inside Out 2 is ultimately about accepting the limitations of providing guidance. Joy and Anxiety are both trying to steer Riley down a deliberate path they think is best, but Riley needs to discover her own path rather than have it programmed for her. I appreciated that Anxiety is not treated as some dangerous one-dimensional villain hijacking Riley’s brain. Much like sadness, there is a real psychological purpose for anxiety, to keep us alert and prepared. Now that can certainly go into overdrive, as demonstrated throughout Inside Out 2, including a realistic depiction of a panic attack. It’s about finding balance, though one person’s balance will be inordinately different from another. The stakes may be intentionally low in this movie, all about making the hockey team and being welcomed by the popular girl she may or may not be crushing over (more on that later), but the focus is on the sense of who Riley chooses to be through her life’s inevitable ups and downs. It’s about our response to change as much as it is our response to the presence of anxiety.