Blog Archives

The Wild Robot (2024)

There must be something personally appealing when it concerns movies about hopeful robots that serve as change agents to new communities. WALL-E and The Iron Giant are two of my favorite films of all time, and while The Wild Robot won’t quite enter that all-hallowed echelon, it’s still a heartfelt and lovely movie that can appeal to anyone. We follow Roz (voiced by Lupita Nyong’o), a discarded robot looking for tasks to complete on an island. Fortunately, the robot learns how to communicate with the local wildlife, including a baby goose that our robot feels responsible to train how exactly to be a goose, including how to fly before the advent of winter and the larger flock migrates. The characters are kept pretty simple but that doesn’t mean their emotions are. The movie, based upon a popular children’s book series by Peter Brown, is refreshingly mature about nature’s life cycle, not treating death like a taboo subject too dark for children. The themes of parenting, being different, and finding an accepting home through compassion and courage are all resonant no matter your age, and I’m happy to report that I teared up at several points. The parent-child relationship between the damaged robot and orphaned gosling extends beyond them, inspiring other members of the island’s food chain to work together for common goals and sustainability. There’s a late antagonist thrown in to up the stakes and provide a bit more explosive action, including a magnetic magenta-colored forest fire. The movie doesn’t quite close as strongly as it opens, but writer/director Chris Sanders (Lilo & Stitch, How to Train Your Dragon) knows innately how to execute at such a high level where even simple characters and familiar themes have fully developed stories with soaring emotions that arrive fully earned.

There must be something personally appealing when it concerns movies about hopeful robots that serve as change agents to new communities. WALL-E and The Iron Giant are two of my favorite films of all time, and while The Wild Robot won’t quite enter that all-hallowed echelon, it’s still a heartfelt and lovely movie that can appeal to anyone. We follow Roz (voiced by Lupita Nyong’o), a discarded robot looking for tasks to complete on an island. Fortunately, the robot learns how to communicate with the local wildlife, including a baby goose that our robot feels responsible to train how exactly to be a goose, including how to fly before the advent of winter and the larger flock migrates. The characters are kept pretty simple but that doesn’t mean their emotions are. The movie, based upon a popular children’s book series by Peter Brown, is refreshingly mature about nature’s life cycle, not treating death like a taboo subject too dark for children. The themes of parenting, being different, and finding an accepting home through compassion and courage are all resonant no matter your age, and I’m happy to report that I teared up at several points. The parent-child relationship between the damaged robot and orphaned gosling extends beyond them, inspiring other members of the island’s food chain to work together for common goals and sustainability. There’s a late antagonist thrown in to up the stakes and provide a bit more explosive action, including a magnetic magenta-colored forest fire. The movie doesn’t quite close as strongly as it opens, but writer/director Chris Sanders (Lilo & Stitch, How to Train Your Dragon) knows innately how to execute at such a high level where even simple characters and familiar themes have fully developed stories with soaring emotions that arrive fully earned.

Nate’s Grade: B+

It Ends With Us (2024)

If you’re expecting a charming romantic drama about a young woman moving back home and finding new love and rekindling romance with a past love, then you might be better off scanning the Hallmark Channel. For those blissfully unfamiliar with author Colleen Hoover, It Ends With Us is her best-seller about domestic abuse. The Dickensian-named Lily Bloom (Blake Lively), who wants to open a flower store, comes back home after her abusive father passes, and she reconnects with Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Sklenar), her childhood love who her father chased away. She also falls for child neurosurgeon Ryle Kincaid (director Justin Baldoni) who happens to be an abuser. It takes an hour into the movie before Ryle physically harms Lily, which means the movie up until that point is paced and structured like a typical romantic drama and we’re meant to find him smooth and desirable. Perhaps Hoover and the filmmakers are trying to better place us in the position of the abused spouse, providing context that some might use to excuse toxic behavior and red flags, but if they wanted to set up more of a love triangle, they’ve done a poor job. Atlas mostly appears in flashbacks as the idealistic, impoverished boyfriend she kind of takes in. He then re-establishes himself in the present with a successful fancy restaurant, and the movie more or less just puts him on a shelf and says, “When she’s ready to have someone nice, she’ll settle back with that bland guy from her past.” Feels like we’re spending too much time on stories that we shouldn’t, and less time on ones we should. It’s grandiose soap opera plotting for serious subject matter. Credit director/co-star Baldoni for not soft-pedaling the treacherous nature of his character’s control and insecurity. There’s a great deal of very uncomfortable and disturbing abuse sequences, including a rape, for a PG-13 movie. Domestic abuse, and growing up in the shadow of domestic abuse, makes for some very challenging viewing. If the movie was more insightful, or honest, or even nuanced, it might be worth enduring the discomfort of its two hours. It’s not. It’s just punishing.

If you’re expecting a charming romantic drama about a young woman moving back home and finding new love and rekindling romance with a past love, then you might be better off scanning the Hallmark Channel. For those blissfully unfamiliar with author Colleen Hoover, It Ends With Us is her best-seller about domestic abuse. The Dickensian-named Lily Bloom (Blake Lively), who wants to open a flower store, comes back home after her abusive father passes, and she reconnects with Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Sklenar), her childhood love who her father chased away. She also falls for child neurosurgeon Ryle Kincaid (director Justin Baldoni) who happens to be an abuser. It takes an hour into the movie before Ryle physically harms Lily, which means the movie up until that point is paced and structured like a typical romantic drama and we’re meant to find him smooth and desirable. Perhaps Hoover and the filmmakers are trying to better place us in the position of the abused spouse, providing context that some might use to excuse toxic behavior and red flags, but if they wanted to set up more of a love triangle, they’ve done a poor job. Atlas mostly appears in flashbacks as the idealistic, impoverished boyfriend she kind of takes in. He then re-establishes himself in the present with a successful fancy restaurant, and the movie more or less just puts him on a shelf and says, “When she’s ready to have someone nice, she’ll settle back with that bland guy from her past.” Feels like we’re spending too much time on stories that we shouldn’t, and less time on ones we should. It’s grandiose soap opera plotting for serious subject matter. Credit director/co-star Baldoni for not soft-pedaling the treacherous nature of his character’s control and insecurity. There’s a great deal of very uncomfortable and disturbing abuse sequences, including a rape, for a PG-13 movie. Domestic abuse, and growing up in the shadow of domestic abuse, makes for some very challenging viewing. If the movie was more insightful, or honest, or even nuanced, it might be worth enduring the discomfort of its two hours. It’s not. It’s just punishing.

Nate’s Grade: D

Uglies (2024)

Even though Uglies is based upon a book series that hails back to 2005, it feels so much like it was developed in a vat subsisting on the runny discharge from other YA dystopian projects, finally settling into an unappealing mixture of familiar tropes. In this post-apocalyptic future world, society has rebuilt itself with a caste system that celebrates beauty. Teenagers undergo surgical operations and brainwashing to make themselves a member of the Pretties, the cool kids. If you’re even remotely familiar with YA storytelling, you can likely guess exactly where the movie goes from here. Our heroine is called Squint because society seems to think her eyes need work. There’s another character named Nose for the same reason, meaning that upon birth, I guess the doctor just holds up you baby and starts verbally roasting them. Squint is played by Netflix staple Joey King (The Kissing Booth, A Family Affair) and therein lies one of our central adaptation problems. The rules of Hollywood will not allow unattractive lead actors in movies like this, so the filmmakers give her brunette hair and less makeup, as if we’re supposed to find movie star Joey King to be naturally hideous. It’s the same with every actor in the movie. Now, if you were going to adapt this to a visual medium, maybe you lean into the visual contrasts in a more specific manner: all the “Uglies” are minorities and all the “Pretties” are lighter-skinned or white. That would bring an added colorism commentary but it would also be steering the movie into a more dangerous relevancy. The plot is all simplistic high school battle lines about individualism versus conformity, self-acceptance versus assimilation, though the optics of having a trans woman (Laverne Cox) being the evil head of education forcing surgery on teens and brainwashing them feels quite problematic considering grotesque conservative theories endangering the lives of actual trans people. There is one surprise in Uglies, one that I’ll spoil for you, dear reader. It doesn’t end. It sets up the next adventure with Squint supposedly bringing down the corrupt society from the inside, but I challenge anyone not familiar with the book series to be that compelled to put right the unresolved storylines and character arcs from this stalled launch.

Nate’s Grade: C-

I Saw the TV Glow (2024)/ The Watchers (2024)

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

Nate’s Grade: B

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

Nate’s Grade: C

Robot Dreams (2023)

What a delightfully tender little movie Robot Dreams proves to be. It’s based on a picture book and its story is mostly about a lonely Dog who orders a build-your-own-robot for companionship and their friendship. Much of the movie hinges on the Robot being trapped on a Long Island beach closed for the season, so our intrepid Dog must go on living in his New York City apartment through the seasons while he waits to rescue his friend. The movie is wordless and based upon a picture book, but that doesn’t mean this is chiefly kid’s stuff. It touches upon the profound with such elegance and efficiency, brilliantly relatable and recognizably human. It’s all about our need for connections, and even when they are separated, both the Dog and Robot find other connections with other characters, and then it comes back to our worry that they won’t actually reunite after being apart for the majority of the movie. I was reading some gay coding between the two as well but maybe that was my own projection. My nine-year-old son was quite taken with the movie and could easily follow along, though he was also very much not a fan of the bittersweet ending, his first taste of providing the whole “what you need, not what you want” conclusion. Robot Dreams is lovingly realized, its animation so clean and crisp with wonderful characters populating an alternative 1980s NYC. It’s simple and sweet and irresistible.

What a delightfully tender little movie Robot Dreams proves to be. It’s based on a picture book and its story is mostly about a lonely Dog who orders a build-your-own-robot for companionship and their friendship. Much of the movie hinges on the Robot being trapped on a Long Island beach closed for the season, so our intrepid Dog must go on living in his New York City apartment through the seasons while he waits to rescue his friend. The movie is wordless and based upon a picture book, but that doesn’t mean this is chiefly kid’s stuff. It touches upon the profound with such elegance and efficiency, brilliantly relatable and recognizably human. It’s all about our need for connections, and even when they are separated, both the Dog and Robot find other connections with other characters, and then it comes back to our worry that they won’t actually reunite after being apart for the majority of the movie. I was reading some gay coding between the two as well but maybe that was my own projection. My nine-year-old son was quite taken with the movie and could easily follow along, though he was also very much not a fan of the bittersweet ending, his first taste of providing the whole “what you need, not what you want” conclusion. Robot Dreams is lovingly realized, its animation so clean and crisp with wonderful characters populating an alternative 1980s NYC. It’s simple and sweet and irresistible.

Nate’s Grade: A-

The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes (2023)

Who exactly was watching The Hunger Games and thought to themselves, I wonder if this evil old fascist dictator played by Donald Sutherland was ever young and sexy and in love? Well fear not, whomever you are, because 2023 gave us the adaptation of The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes, the far too long adaptation of Suzanne Collins’ prequel book, thus granting the studio more material to grind into products. I guess we should all be grateful that this wasn’t stretched into two movies like the original plan. Taking place 60 years prior to the events of the first movie, young Coriolanus Snow (Tom Blyth) is trying to financially secure his family’s safety in the Capitol, and he’s also mentoring one of the district combatant’s in the tenth annual Hunger Games death match. His charge is District 12’s Lucy Gray Baird (Rachel Zegler), a feisty Romani-esque young woman who uses song as her vehicle for rebellion, and young Snow has to coach her to victory if he has any hope of righting his family’s lost standing. Fortunately, the Hunger Games behind-the-scenes coordination and development is interesting, and filled with top-level actors living it up in these outsized roles (Viola Davis, you national treasure). The deadly games themselves are confined to one dilapidated arena and are visually engaging even in such a limited space. Unfortunately, the would-be Romeo and Juliet romance between Snow and Lucy Gray is far less engaging, and young Snow proves to be a handsome bore. There was potential here in exploring the origin of a monster but the villainy seems awfully contrived to push him along on an arc, with several drastic personal decisions absent believable development. We’re talking big character leaps here, the kind that I can’t even really explain except, “Well, I guess he just had it in him the whole time.” The hazy rationalization and rushed development reminded me of Anakin Skywalker’s underwhelming descent into the dark side. Songbirds & Snakes is only really going to work for the diehard fans of the franchise asking for a little more time in this dystopian universe and daydreaming about the washboard abs and baby blue eyes of their favorite older fascist.

Who exactly was watching The Hunger Games and thought to themselves, I wonder if this evil old fascist dictator played by Donald Sutherland was ever young and sexy and in love? Well fear not, whomever you are, because 2023 gave us the adaptation of The Ballad of Songbirds & Snakes, the far too long adaptation of Suzanne Collins’ prequel book, thus granting the studio more material to grind into products. I guess we should all be grateful that this wasn’t stretched into two movies like the original plan. Taking place 60 years prior to the events of the first movie, young Coriolanus Snow (Tom Blyth) is trying to financially secure his family’s safety in the Capitol, and he’s also mentoring one of the district combatant’s in the tenth annual Hunger Games death match. His charge is District 12’s Lucy Gray Baird (Rachel Zegler), a feisty Romani-esque young woman who uses song as her vehicle for rebellion, and young Snow has to coach her to victory if he has any hope of righting his family’s lost standing. Fortunately, the Hunger Games behind-the-scenes coordination and development is interesting, and filled with top-level actors living it up in these outsized roles (Viola Davis, you national treasure). The deadly games themselves are confined to one dilapidated arena and are visually engaging even in such a limited space. Unfortunately, the would-be Romeo and Juliet romance between Snow and Lucy Gray is far less engaging, and young Snow proves to be a handsome bore. There was potential here in exploring the origin of a monster but the villainy seems awfully contrived to push him along on an arc, with several drastic personal decisions absent believable development. We’re talking big character leaps here, the kind that I can’t even really explain except, “Well, I guess he just had it in him the whole time.” The hazy rationalization and rushed development reminded me of Anakin Skywalker’s underwhelming descent into the dark side. Songbirds & Snakes is only really going to work for the diehard fans of the franchise asking for a little more time in this dystopian universe and daydreaming about the washboard abs and baby blue eyes of their favorite older fascist.

Nate’s Grade: C+

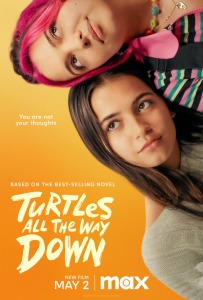

The Idea of You/ Turtles All the Way Down (2024)

The Idea of You is the kind of movie that Hollywood used to crank out, a romantic drama star vehicle based upon a popular novel and with a skilled director, and now it forgoes any theatrical run and ends up as another option on a streaming channel. The Idea of You follows a 40-year-old divorced single mom played by Anne Hathaway who also happens to run an L.A. art gallery and has a meet-cute with a handsome boy band member (Nicholas Galitzine, Purple Hearts) at the Coachella music festival (oh the magic lives of people never having to worry about bills in rom-coms). they hit it off, and the rest of the movie is whether or not they can make a romance work. There’s a 15-year age gap that she feels very self-conscious about as an older woman (“older” by Hollywood standards). She’s this formerly normal woman who wants to date one of the most famous music stars in the world who isn’t always available, but most of the problems and conflicts stem from the perceived issues of the age gap. It’s a charming romance that’s more dramatic than it is comedic, and Hathaway is quite good as our lead plucked from obscurity. Though the many scenes of our smitten boy band member making googly eyes at Hathaway as he reminds her how attractive she is, and as she bashfully demurs, are a little much (it’s Anne Hathaway, notorious horrible-looking human specimen, right?). As a core romance, the movie works well under the guidance of director and co-writer Michael Showalter (The Big Sick), and it’s more adult than I was expecting. It’s rated R for language and it’s also more sensual, but it’s also more adult as in looking at the ramifications of this relationship in a mature perspective, from the terrors of paparazzi imposition to her daughter being harassed at school. The portrayal is thus more engaging and engrossing and feels above the more flippant and flimsy romances that would settle for far less. Though be warned: there are several sequences of singing and serenading which might cause you to shrink awkwardly inward on your couch. Surprisingly thoughtful, and relatively romantic, The Idea of You is a charming reminder of the appeal of comforting tales of love blossoming in unexpected places and pretty people allowing themselves the choice to be happy.

Based on best-selling YA author John Green’s 2017 novel, Turtles All the Way Down is a very accessible and very affecting glimpse at living with mental illness, obsessive compulsive disorder, and intrusive thoughts. Aza (Isabela Merced) has an overwhelming inner monologue that sabotages her daily life in high school and carries her along anxious thought diversions, constantly relating to some illness growing inside her that she needs to cleanse. This is the crux of the story, along with her relationship with her super eager best friend. There’s a romantic side plot where she helps out a rich classmate whose billionaire dad has gone missing, which feels like a plot device to necessitate the two characters spending time together. The standout aspect of this adaptation by writer/director Hannah Marks (Don’t Make Me Go) is its unsparing and honest yet hopeful depiction of mental health and intrusive thoughts. Merced (Dora and the Lost City of Gold, Madame Web) is excellent and deeply empathetic as this woman held hostage by her wayward thoughts and impulses. It’s a performance that goes beyond easy depictions of aloof detachment or exaggerated histrionics, shedding any acting techniques that are too mannered or attention-seeking. Marks’ direction helps reflect Aza’s troubled mind with rapid insert edits and voice over to communicate the intrusive thoughts and maelstrom of spiraling negative emotions. If you’re a fan of Green’s popular novels, or YA-themed literature, or even just honest attempts to empathize with teens in turmoil, then Turtles All the Way Down is worth battling through any negative thoughts to finish and relish the journey.

Nate’s Grades:

The Idea of You: B

Turtles All the Way Down: B+

Oppenheimer (2023)

I finally did it. I watched all three hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one half of the biggest movie-going event of 2023, and arguably the most smarty-pants movie to ever gross a billion dollars. It was a critical darling all year long, sailed through its awards season, and racked up seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director for Nolan, a coronation for one of Hollywood’s biggest artists whose name alone is each new project’s biggest selling point. I’ve had friends falling over themselves with rapturous praise, and I’m sure you have too, dear reader, so the danger becomes raising your expectations to a level that no movie could ever meet. As I watched all 180 lugubrious minutes of this somber contemplation of man’s hubris, I kept thinking, “All right, this is good, but is it all-time-amazing good?” I can’t fully board the Oppenheimer hype train, and while I respect the movie and its exceptional artistry, I also question some of the key creative decision-making that made this movie exactly what it is, bladder-busting length and all.

I finally did it. I watched all three hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one half of the biggest movie-going event of 2023, and arguably the most smarty-pants movie to ever gross a billion dollars. It was a critical darling all year long, sailed through its awards season, and racked up seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director for Nolan, a coronation for one of Hollywood’s biggest artists whose name alone is each new project’s biggest selling point. I’ve had friends falling over themselves with rapturous praise, and I’m sure you have too, dear reader, so the danger becomes raising your expectations to a level that no movie could ever meet. As I watched all 180 lugubrious minutes of this somber contemplation of man’s hubris, I kept thinking, “All right, this is good, but is it all-time-amazing good?” I can’t fully board the Oppenheimer hype train, and while I respect the movie and its exceptional artistry, I also question some of the key creative decision-making that made this movie exactly what it is, bladder-busting length and all.

As per Nolan’s non-linear preferences, we’re bouncing back and forth between different timelines. The main story follows Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as an upstart theoretical physicist creating his own academic foothold and then being courted to join the Manhattan Project to beat the Nazis in the formation of a nuclear bomb. The other timeline concerns the Senate approval hearing for Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), the former head of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) with a checkered history with Oppenheimer after the war. A third timeline, serving as a connecting point, involves Oppenheimer undergoing a closed-door questioning over the approval of his security clearance, which brings to light his life of choices and conundrums.

If I was going to be my most glib, I would characterize Oppenheimer in summary as, “Man creates bomb. Man is then sad.” There’s much more to it, obviously, and Nolan is at his most giddy when he’s diving into the heavy minutia of how the project came about, the many brilliant minds working in tandem, and sometimes in conflict, to usher in a new era of science and energy. Of course it also has radical implications for the world outside of academic theory. The world will never be the same because of Oppenheimer dramatically upgrading man’s self-destructive power. The accessible cautionary tale reminds me of a Patton Oswalt stand-up line: “We’re science: all about ‘coulda,’ no about ‘shoulda.’” Oh the folly of man and how it endures.

If I was going to be my most glib, I would characterize Oppenheimer in summary as, “Man creates bomb. Man is then sad.” There’s much more to it, obviously, and Nolan is at his most giddy when he’s diving into the heavy minutia of how the project came about, the many brilliant minds working in tandem, and sometimes in conflict, to usher in a new era of science and energy. Of course it also has radical implications for the world outside of academic theory. The world will never be the same because of Oppenheimer dramatically upgrading man’s self-destructive power. The accessible cautionary tale reminds me of a Patton Oswalt stand-up line: “We’re science: all about ‘coulda,’ no about ‘shoulda.’” Oh the folly of man and how it endures.

For the first two hours, the focus is the secretive Manhattan Project out in the New Mexico desert and its myriad logistical challenges, all with the urgency of being in a race with the Nazis who already have a head start (their break is Hitler’s antisemitism pushing out brilliant Jewish minds). That urgency to beat Hitler is a key motivator that allows many of the more hand-wringing members to absolve those pesky worries; Oppenheimer says their mission is to create the bomb and not to determine who or when it is used. That’s true, but it’s also convenient moral relativism, essentially saying America needs to do bad things so that the Germans don’t do worse things, a line of adversarial thinking that hasn’t gone away, only the name of the next competitor adjusts. This portion of the movie works because it adopts a similarly streamlined focus of smart people working together against a tight deadline. Looking at it as a problem needing to surmount allows for an engaging ensemble drama complete with satisfying steps toward solutions and breakthroughs. It makes you root for the all-star team and excitedly follow different elements relating to nuclear fusion and fission that you would have had no real bearing before Nolan’s intellectual epic. For those two galloping hours, the movie plays almost like a brainy heist team trying to pull together the ultimate job.

It’s the time afterwards where Oppenheimer expands upon the lasting consequences where the movie finds its real meaning as well as loses me as a viewer. The legacy of the bomb is one that modern audiences are going to be readily familiar with 80 years after the events that precipitated their arrival, and they haven’t exactly been shelved or become the world war deterrent hoped for. As one of Oppenheimer’s physicists says, a big bomb only works until someone creates a bigger bomb, and then the arms race starts all over again fighting for incremental supremacy when it comes to whether one’s military might could destroy the world ten times or twelve times over. When Oppenheimer begins having reservations of what he has brought into this world is when his character starts becoming more dynamic, but it’s also too late. He can’t undo what he’s done, the world isn’t going back to a safer existence before nuclear arms, so his tears and fears come as short shrift. There’s a scene where Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), castigates him and says, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then make all of us to feel sorry for you when there are consequences.” Now this is in reference to a different personal failing of our protagonist, but the message resonates; however, I don’t know if this is Nolan’s grand takeaway. The movie in scope and ambition wants to set up this man as a tragic figure that gave birth to our modern world, but like President Truman says, it’s not about who created the bomb but who uses it. Oppenheimer is treated like a harbinger of regret, but I don’t think the story has enough to merit this examination, which is why Oppenheimer peters out after the bomb’s immediate aftermath.

It’s the time afterwards where Oppenheimer expands upon the lasting consequences where the movie finds its real meaning as well as loses me as a viewer. The legacy of the bomb is one that modern audiences are going to be readily familiar with 80 years after the events that precipitated their arrival, and they haven’t exactly been shelved or become the world war deterrent hoped for. As one of Oppenheimer’s physicists says, a big bomb only works until someone creates a bigger bomb, and then the arms race starts all over again fighting for incremental supremacy when it comes to whether one’s military might could destroy the world ten times or twelve times over. When Oppenheimer begins having reservations of what he has brought into this world is when his character starts becoming more dynamic, but it’s also too late. He can’t undo what he’s done, the world isn’t going back to a safer existence before nuclear arms, so his tears and fears come as short shrift. There’s a scene where Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), castigates him and says, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then make all of us to feel sorry for you when there are consequences.” Now this is in reference to a different personal failing of our protagonist, but the message resonates; however, I don’t know if this is Nolan’s grand takeaway. The movie in scope and ambition wants to set up this man as a tragic figure that gave birth to our modern world, but like President Truman says, it’s not about who created the bomb but who uses it. Oppenheimer is treated like a harbinger of regret, but I don’t think the story has enough to merit this examination, which is why Oppenheimer peters out after the bomb’s immediate aftermath.

It reminded me of an Oscar favorite from 2015, Adam McKay’s The Big Short, a true-ish account of real people profiting off the worldwide financial meltdown from 2008. It fools you into taking on the perspective of its main characters who present themselves as underdogs, keepers of a secret knowledge that they are trying to benefit from before an impending deadline. Likewise, the conclusion also makes you question whether you should have been rooting for this scheme all along since it was predicated on the economy crashing; these guys got their money but how many lives were irrevocably ruined to make their big score? With The Big Short, the movie-ness of its telling is part of McKay’s trickery, to ingratiate you in this clandestine financial world and to treat it like a heist or a con, and then to reckon whether you should have ever been rooting for such an adventure. Oppenheimer has a similar effect, lulling you with its admitted entertainment factor and beat-the-deadline structure. Once the mission is over, once the heroes have “won,” now the game doesn’t seem as fun or as justifiable. Except Oppenheimer could have achieved this effect with a judicious resolution rather than an entire third hour of movie shuffled throughout the other two like a mismatched deck of cards.

The last hour of the movie features a security clearance interrogation and a Senate confirmation hearing, neither of which have appealing stakes for an audience. After we watch the creation of a bomb, do we really care whether or not this one testy guy gets approved for a cabinet-level position or whether Oppenheimer might get his security clearance back? I understand that these stakes are meaningful for the characters, both essentially on trial for their lives and connections, but Nolan hasn’t made them as necessary for the audience. They’re really systems for exposition and re-examination, to play around with time like it was having a conversation with itself. It’s a neat effect when juggled smoothly, like when Past Oppenheimer is being interviewed by a steely and suspicious military intelligence office (Casey Affleck) while Future Oppenheimer laments to his project superior (Matt Damon) and then Even More Future Oppenheimer regrets his lack of candor to the review board. The shifty wheels-within-wheels nature of it all can be astounding when it’s all firing in alignment, but it can also feel like Nolan having a one-sided conversation with himself too often. It’s another reminder of the layers of narrative trickery and obfuscation that have become staples of a Christopher Nolan movie (I don’t think he could tell a knock-knock joke without making it at least nonlinear). The opposition to Oppenheimer is summarized by Strauss but I would argue the man didn’t need a public witch hunt to rectify what he’s done.

The last hour of the movie features a security clearance interrogation and a Senate confirmation hearing, neither of which have appealing stakes for an audience. After we watch the creation of a bomb, do we really care whether or not this one testy guy gets approved for a cabinet-level position or whether Oppenheimer might get his security clearance back? I understand that these stakes are meaningful for the characters, both essentially on trial for their lives and connections, but Nolan hasn’t made them as necessary for the audience. They’re really systems for exposition and re-examination, to play around with time like it was having a conversation with itself. It’s a neat effect when juggled smoothly, like when Past Oppenheimer is being interviewed by a steely and suspicious military intelligence office (Casey Affleck) while Future Oppenheimer laments to his project superior (Matt Damon) and then Even More Future Oppenheimer regrets his lack of candor to the review board. The shifty wheels-within-wheels nature of it all can be astounding when it’s all firing in alignment, but it can also feel like Nolan having a one-sided conversation with himself too often. It’s another reminder of the layers of narrative trickery and obfuscation that have become staples of a Christopher Nolan movie (I don’t think he could tell a knock-knock joke without making it at least nonlinear). The opposition to Oppenheimer is summarized by Strauss but I would argue the man didn’t need a public witch hunt to rectify what he’s done.

Lest I sound too harsh on Nolan’s latest, there are some virtuoso sequences that are spellbinding with technical artists working to their highest degree of artistry. The speech Oppenheimer gives to his Los Alamos colleagues is a horrifying lurch into a jingoistic pep rally, like he’s the big game coach trying to rally the team. The way the thundering stomps on the bleachers echo the rhythms of a locomotive in motion, driving forward at an alarming rate of acceleration, and then how Nolan drops the background sound so all we hear is Oppenheimer’s disoriented speech while the boisterous applause is muted, it’s all masterful to play with our sense of dread and remorse. This is who this man has become, and his good intentions of scientific discovery will be rendered into easily transmutable us-versus-them fear mongering politics. The ending imagery of Oppenheimer envisioning the world on fire is the exact right ending and hits with the full disquieting force of those three hours. The meeting with Harry Truman (Gary Oldman) is splendid for how undercutting it plays. Kitty’s interview at the hearing is the kind of counter-punching we’ve been waiting for and is an appreciated payoff for an otherwise underwritten character stuck in the Concerned Wife Back at Home role. The best parts are when Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves (Damon) are working in tandem to put together their team and location, as that’s when the movie feels like a well orchestrated buddy movie I didn’t know I wanted. The sterling cinematography, musical score, editing, all of the technical achievements, many of which won Oscars, are sumptuously glorious and immeasurably add to Nolan’s big screen vision.

I think I may understand why the subject of sex is something Nolan has conspicuously avoided before. Much has been made about the sex scenes and nudity in Oppenheimer, which seem to be the crux of Florence Pugh’s performance as Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s communist mistress through the years. The moment of Oppenheimer sitting during his hearing about his sexual tryst with an avowed communist leads to him imagining himself in the nude, exposed and vulnerable to these prying eyes and their judgment. Then Kitty imagines seeing Pugh atop her husband in his hearing seat, staring directly at her, and this sequence communicated both of their internal states well and felt justified. It’s the origin of the famous “I am become death” quote where the movie enters an unexpected level of cringe for a movie this serious. I was not prepared for this, so mild spoilers ahead if you care about such things, curious reader. We’re dropped into a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Jean where she takes a break to peruse his library shelves. She’s impressed that he has a Hindu text and pins it against her naked chest and slides atop Oppenheimer once again, requesting he read it to her rather than summarize it. “I am become death,” he utters, as he reads the Hindu Book of the Dead off Pugh’s breasts while they continue to have sex. Yikes. A big ball of yikes. If this is what’s in store, please go back to a sexless universe of men haunted by their lost women.

I think I may understand why the subject of sex is something Nolan has conspicuously avoided before. Much has been made about the sex scenes and nudity in Oppenheimer, which seem to be the crux of Florence Pugh’s performance as Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s communist mistress through the years. The moment of Oppenheimer sitting during his hearing about his sexual tryst with an avowed communist leads to him imagining himself in the nude, exposed and vulnerable to these prying eyes and their judgment. Then Kitty imagines seeing Pugh atop her husband in his hearing seat, staring directly at her, and this sequence communicated both of their internal states well and felt justified. It’s the origin of the famous “I am become death” quote where the movie enters an unexpected level of cringe for a movie this serious. I was not prepared for this, so mild spoilers ahead if you care about such things, curious reader. We’re dropped into a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Jean where she takes a break to peruse his library shelves. She’s impressed that he has a Hindu text and pins it against her naked chest and slides atop Oppenheimer once again, requesting he read it to her rather than summarize it. “I am become death,” he utters, as he reads the Hindu Book of the Dead off Pugh’s breasts while they continue to have sex. Yikes. A big ball of yikes. If this is what’s in store, please go back to a sexless universe of men haunted by their lost women.

It’s easy to be swept away by all the ambition of Nolan’s Oppenheimer, a Great Man of History biopic that I think could have been better by being more judiciously critical of its subject. It’s a thoroughly well-acted movie where part of the fun is seeing known and lesser known name actors populate what would have been, like, Crew Member #8 roles for the sake of being part of this movie (Rami Malek as glorified clipboard-holder). Oppenheimer takes some wild swings, many of them paying off tremendously and also a few that made me scratch my head or reel back. It’s a demonstrably good movie with top-level craft, but I can’t quite shake my misgivings that enough of the movie could have been lost to history as well.

Nate’s Grade: B

You must be logged in to post a comment.