Blog Archives

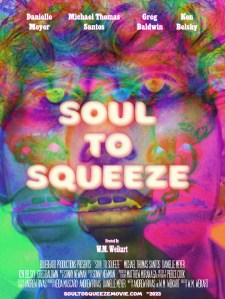

Soul to Squeeze (2025)

It’s been some time since I’ve reviewed an Ohio-made indie (having a baby and adjusting to a new job will do that). My goal has always been to discover the rare diamonds in the rough and to provide professional film criticism to these smaller-scale movies trying to make some noise. I’ve been doing this for a few years now and I’ll admit I haven’t found that many diamonds, so to speak. My wife has long since stopped watching these movies with me and declared me a masochist for continuing this quest. What can I say, I’m still hopeful to discover what Ohio filmmakers can do when given a platform. One such filmmaker, who has since relocated from Ohio to the City of Angels, is W.M. Weikart. I reviewed his 2019 short film Pure O and we have several mutual friends. He asked me to review his next project, a feature-length movie shot with some Ohio-bred talent in front of and behind the camera, so I’m considering Soul to Squeeze as Ohio-indie-adjacent. It’s a trippy, beguiling experience, and it’s one that will prove befuddling to some but is an experience that gets better with every additional minute.

The story itself is relatively simple. Jacob (Michael Thomas Santos, CSI: Vegas) is a young coed who agrees to be the subject of a mysterious experiment. He lives in a house for days and experiences a series of bizarre auditory and visual hallucinations, picking at his mind, memories, and hidden trauma that he’s been trying to ignore for years. Or are they actually hallucinations after all? Can his mind survive?

These experimental/psychological triptych kinds of movies hinge on a few points of potential viewer engagement. First, the most obvious is simply being interesting and memorable in its weirdness. If you’re going for a crazy sensory experience, it helps if there’s actually something crazy worth watching. This was one of my biggest issues with the 2023 horror indie Skinamarink, a strange nightmare that mostly felt like the same ten boring images jumbled around for 80 very tedious minutes of dashed hopes. There’s only so much formless imagery I can watch without some larger connection, and if your movie is going to live or die based upon your outlandish nightmare imagery, then you better rise to the challenge. Skinamarink did not. Thankfully Soul to Squeeze has a larger agenda that reveals itself over the course of its 80-minute running time. We have a character trying to hide from some trauma he’d rather ignore, so we know this experience will force him to confront those feelings and, hopefully, find some way to process his intense emotions and come out the other side a better person. Or it will drive him completely mad. Either storytelling path offers intrinsic entertainment value. There’s purpose under the imagery so it’s not all abstract nonsense waiting for someone else to project meaning onto the disconnected pieces.

Now, it takes a little long to get going to begin to reveal that trauma and that connectivity. For the first forty minutes, weird things are going down without much in the way of a larger set of rules, which could have benefited the engagement, such as disturbing or confounding visions happening between certain hours of the day, allowing our protagonist time to anxiously dread their arrival. Or there could be an escalation in the intensity of the visions and their duration. There could also be the question over whether the visions are real or not, especially if they’re occurring after he’s forced to eat the provided food in the house. Perhaps he even tries to abstain from eating to then discover they still come like dreadful clockwork. Unraveling past residents of this experiment could also foretell what possible fates, both helpful and harmful, could await. Our protagonist could also try and escape as the visions get more personal and find he cannot escape. The character could be a little more active. Jacob seems very compliant for a wounded character undergoing psychological experimentation, which begs the question why he would continue with this treatment after it begins picking away at the secret he doesn’t want to face. There are other directions that the main character could have gone through while we waited for the larger thematic clarity to come into focus with the visions after 40-minutes of atmospheric noodling.

When you’re going for a more experimental narrative with heavy visual metaphors, it can be tricky to find a balance between arty and pretentious, or, to put it in other words, between David Lynch and student films. This balance is tipped toward the latter early, especially when I think a blue flower comes to life and is… a French woman… spouting platitudes before turning back into a flower. It’s stuff like that which can seem a little daft but without the intention of weird humor. In contrast, there’s a strange but amusing scene where our character comes across a sitting mermaid on display in a museum. She literally eats a pearl necklace from Jacob’s hands and then smiles mischievously as it reappears around her neck, now her own possession. There is a larger metaphorical connection here that’s revealed later, with the necklace having a connection to Jacob’s traumatic past and even the concept of the mermaid too. There’s a phone conversation that we get both sides of that ends up starting as one of the earliest points of confusion and agitation for Jacob and then, by its return, serves as an unexpected vehicle for our protagonist’s emotional growth and reflection. It’s a clever and rather satisfying creative boomerang.

Soul to Squeeze impressively masks its low-budget nature through creative choices and elevated technical craft. Weikart has a natural eye for visual composition and lighting especially, so there’s nary a moment where the movie isn’t at least appealing to the eyes. Having a director who can frame an engaging shot is a godsend when you’re primarily going to be stuck in a single location for 80 minutes. A smart and talented visual artist can really hide the limitations of a low budget well. This is also by far one of the best sounding low-budget indies I’ve heard. The sound mixing is impeccably professional and the score by Sonny Newman (Burn the Witch) is very pleasant and evocative and soothing when it wants to be. Sound design is one of the biggest areas that holds back so many micro-budget film productions, and it’s so refreshing to have a movie not only where sound has been given great attention but also incorporated into the presentation and experiences in meaningful and artistic ways. The visuals can be rather eye-catching, like when Jacob’s TV transforms into a multi-screen monster where eyeballs and a giant mouth take up residence on the various screens, and aided by a slick sound design, it all allows the sensory experience to be even more compelling and accessible. As the film progresses, the bigger picture comes into focus, which means more exposition is thrown at the viewer. Weikart and his team cleverly find ways to present the information through a series of sufficient images and sounds that imply plenty with minimal (some of the sound and picture arrangements can take on a certain true crime dramatic recreation feel). I don’t have a final budget number but it looks better than many indies I’ve seen with considerably higher budgets.

There is one very significant technical choice that I wish had been more essentially incorporated into the story of Soul to Squeeze. As its promotional materials declare, this is the “the first film ever to have a continuously changing aspect ratio throughout the entire film. It begins in a 4:3 aspect ratio and expands out to a 2.35:1 by the end.” For the layman, that means throughout the film the aspect ratio is changing from the old boxy TV standard to a wider and wider widescreen. Now, you could make an argument that this is meant to represent the progression of Jacob’s thinking, that his world is literally expanding, but if that’s the case it feels a little too metaphorical to land as an essential tool for this story to be told at its best. It’s kind of neat but ultimately feels more like a gimmick. Perhaps the nights could have been labeled sequentially, and with each additional night the aspect ratio alters, expanding the horizons. You could even make it a Wizard of Oz motif, with Jacob opening a door and coming out the other end with a different aspect ratio to communicate the transition to a new plane of thinking and reality. Without calling more attention to its changes, and without connecting it more deliberately with the onscreen action, it becomes only a slightly noticeable visual choice over time that may go ignored by most.

By design, Soul to Squeeze is meant to be mystifying and experimental, which will try some people’s patience if they don’t find the ensuing imagery and weirdness to be entertaining. I wish there was more of what I appreciated in the second half to be present in the first half, and I’ll freely admit that I might have missed some of those clues and connective tissue just due to the strange and abstract nature of the movie. I was never bored and often amused at the various ideas that animate the movie (a game show host narrating breakfast is quite surreal and hilarious). The movie looks good, sounds good, and moves along at a fitting pace. The biggest gripe I have with these kinds of movies is whether it will ever add up to anything or is every moment just another in a chain of interchangeable weirdness? With Soul to Squeeze, there is a connection to much of the imagery and hallucinations, so there is a larger design that coalesces. I think there are some specifics that would have potentially aided the overall experience, but adding specificity could deter the immersion and grasping for understanding desired from these kinds of movies. Soul to Squeeze might not be that quintessential diamond in the rough I’m in search of with these Ohio (and Ohio-adjacent) indies, but it’s still a professionally made, creatively engaging, and fairly entertaining curio that can surprise at a moment’s notice.

Nate’s Grade: B

Pure O (2018)

Ideally, every scene in a feature film should have a purpose, whether it’s pushing the overall story forward, informing us about characters and their interior lives, setting up plot points or jokes, or establishing the atmosphere and way of life examined on screen. This is even more necessary with shorts simply from the truncated run time. I was asked to review the short film Pure O, produced by several hard-working, creative types in the Ohio film community. Confession: I know several of the people in front of and behind the camera with this project. I will hold as much of my personal bias back and judge the film on its artistic merits but I thought that should be mentioned upfront.

Ideally, every scene in a feature film should have a purpose, whether it’s pushing the overall story forward, informing us about characters and their interior lives, setting up plot points or jokes, or establishing the atmosphere and way of life examined on screen. This is even more necessary with shorts simply from the truncated run time. I was asked to review the short film Pure O, produced by several hard-working, creative types in the Ohio film community. Confession: I know several of the people in front of and behind the camera with this project. I will hold as much of my personal bias back and judge the film on its artistic merits but I thought that should be mentioned upfront.

Pure O follows Purity Oglander (Stella Singer), the lead singer and guitarist for a grunge band on the verge. She also suffers from a mental condition called Pure OCD (sounds almost like a misguided Calvin Klein cologne), which is an intrusion of harmful thoughts and visions. These thoughts don’t necessarily translate into action but the worry for the recipient is that they might. Purity must navigate her mental illness, the stigma attached to mental illness circa the 90s, and work up the courage to get the help she needs.

It feels like the narrative terrain Pure O mines is our protagonist’s question over who she really is and if she’s ready to embrace change. She’s a local musician who we’re told, via long successions of handy answering machine voice over exposition, has a band “O” on the cusp of its big break. Even titles appear onscreen to tell us this is her “last day of obscurity.” This is a prime conflict as it can push a character outside of their comfort zone and transition from an old life into an uncertain new one. The problem is that this is kept much more as a backdrop of potential conflict; it’s background seasoning. I’m also curious how different her band’s big break is going to be if they’re playing on low-rent, Wayne’s World-style public access television talk shows (“The Mr. Dick Show”). The fact that she blows off this rinky-dink performance and her label is ready to drop the band makes me think that they might not have been so close to that last day of obscurity after all. It’s also not like Purity is returning to her old stomping grounds and reflecting on its influence before she’s whisked to a new level of fame and fortune. She’s still home and presumably with the same people as before.

It feels like the narrative terrain Pure O mines is our protagonist’s question over who she really is and if she’s ready to embrace change. She’s a local musician who we’re told, via long successions of handy answering machine voice over exposition, has a band “O” on the cusp of its big break. Even titles appear onscreen to tell us this is her “last day of obscurity.” This is a prime conflict as it can push a character outside of their comfort zone and transition from an old life into an uncertain new one. The problem is that this is kept much more as a backdrop of potential conflict; it’s background seasoning. I’m also curious how different her band’s big break is going to be if they’re playing on low-rent, Wayne’s World-style public access television talk shows (“The Mr. Dick Show”). The fact that she blows off this rinky-dink performance and her label is ready to drop the band makes me think that they might not have been so close to that last day of obscurity after all. It’s also not like Purity is returning to her old stomping grounds and reflecting on its influence before she’s whisked to a new level of fame and fortune. She’s still home and presumably with the same people as before.

The larger intended focus of acceptance is with her mental illness. That’s an interesting starting point for conflict and an opportunity to visualize some pretty alarming imagery. I was confused whether Purity was just now getting these intruding thoughts. It felt like she had to have had these thoughts before, but her reactions to them seemed so sudden and new, the question over what is going on rather than the recognition that these dark impulses have returned. I think the stronger narrative would have been the acknowledgement that she’s already been struggling to live with these thoughts. That doesn’t mean they are normalized but that it’s not some sudden mental break. I don’t know if there’s any rhyme or reason for what triggers these outbreaks, but we’re treated to two instances or her envisioning brutal assaults and murdering innocents. It’s intended to be a shock to the system, and it delivers mostly, but the overall film tone hampers that.

If I had to single out one element that holds Pure O back from its stated intentions of writer/director W.M. Weikart (Insidious Whispers), that would be its mishmash of tones. There are some pretty significant tonal divergences here with the incursion of psychological horror, but really it’s more the depiction of its everyday world as something akin to a wacky network sitcom. The supporting characters add little to the larger story. They seem to be serving as auditions for a crazy roommate sitcom. There’s the Dickish Dude (Dan Nye), the Soft-Spoken Brainiac (Ann Trinh), Oblivious Girl (Lauren Paulis), Annoying Self-Involved Sister (Sara Morse), Concerned But Out-of-Touch Dad (Carl G. Herrick), and then there’s the even smaller supporting characters of Sardonic Goth Waitress (Kira L. Wilson), Pathetic Local Host (Joe Kidd), and Lisa (Iabou Windimere), a roommate who paints varying degrees of the same circle. Does that sound like the kind of cast of characters for an examination on the crippling effects of mental illness? It feels like an overdose of quirk that doesn’t materialize into something greater or related to Purity. The visit with Purity’s friends amounts to reminding her of the stigma of mental illness, but this same point is served in the next scene with the family lunch when her sister makes the same points. If these characters are meant to reflect our heroine’s journey to some road of acceptance, it’s hard to take that evolution seriously because it’s hard to take them seriously. The sentimental conclusion with Purity getting the help she needs, with the support of her immediate family, feels like another example of a clashing tone keeping the film from gelling properly.

If I had to single out one element that holds Pure O back from its stated intentions of writer/director W.M. Weikart (Insidious Whispers), that would be its mishmash of tones. There are some pretty significant tonal divergences here with the incursion of psychological horror, but really it’s more the depiction of its everyday world as something akin to a wacky network sitcom. The supporting characters add little to the larger story. They seem to be serving as auditions for a crazy roommate sitcom. There’s the Dickish Dude (Dan Nye), the Soft-Spoken Brainiac (Ann Trinh), Oblivious Girl (Lauren Paulis), Annoying Self-Involved Sister (Sara Morse), Concerned But Out-of-Touch Dad (Carl G. Herrick), and then there’s the even smaller supporting characters of Sardonic Goth Waitress (Kira L. Wilson), Pathetic Local Host (Joe Kidd), and Lisa (Iabou Windimere), a roommate who paints varying degrees of the same circle. Does that sound like the kind of cast of characters for an examination on the crippling effects of mental illness? It feels like an overdose of quirk that doesn’t materialize into something greater or related to Purity. The visit with Purity’s friends amounts to reminding her of the stigma of mental illness, but this same point is served in the next scene with the family lunch when her sister makes the same points. If these characters are meant to reflect our heroine’s journey to some road of acceptance, it’s hard to take that evolution seriously because it’s hard to take them seriously. The sentimental conclusion with Purity getting the help she needs, with the support of her immediate family, feels like another example of a clashing tone keeping the film from gelling properly.

The problem for me is that Pure O didn’t quite earn that hopeful, well-traveled ending. The characters were amusing in their brief encounters but didn’t feel like they contributed to the overall larger story. They felt like holdovers from a larger universe of stories making a “special guest appearance.” They felt less like people. That would be fine except I believe we’re meant to feel that sting of hope by the end, that Purity’s family is supporting her accessing therapy. It works, but the ensuing 18 minutes feels cluttered as far as the path taken to get to this conclusion. I think the friends could have been cut entirely especially if the aim is to make Purity feel more like an outcast floating by. It doesn’t feel like all the stops along the way accomplished the goal of moving toward self-acceptance. I’m hard-pressed to really think why she gets the help she needs except for an outpouring of support via answering machine exposition dump. But even those are in response to her near catatonic walk-off from the TV gig, a response that doesn’t seem to earn the outpouring of concern. She does get a phone call from Betty Bosey (Danielle Vettraino), the girl everyone else mocks for being crazy, so perhaps that’s intended as a reminder of self-care.

There are many merits to Pure O. The acting is fairly good throughout and Stella Singer (Choices) is an excellent choice as a lead. She has great moments. Her character is very passive for the majority of the short film, either being talked to or keeping the intruding voices/thoughts at bay, which causes her to feel like a passenger too often. Singer has such a striking, expressive face (seriously, she looks so different with her hair up versus down) that I wanted her to have more opportunities to stretch her acting muscles. It may be fresh in my mind, but she reminded me of Lola Kirke (Gemini). This is a professional looking and edited short film. Even the opening concert scene impressed me with how it was able to tie together an effective looking stage experience. The 90s aesthetic feels very gamely committed, none more so than in wardrobe where each character almost feels entirely defined by a color or extreme look. The strict adherence to stylized costuming does a smart job of telling you about the characters in visual ways, already cuing you without wasting precious time. The sound design is excellent, with the collage of negative voices crashing against her brain like the oncoming surf. The line, “It all went to hell after Karen Carpenter pierced her clit,” is a wonderful non-sequitur that took my breath away. The strange humor of a low-budget public access TV talk show was amusingly absurdist, complete with talking pine tree sidekick and break dancing robot. It’s the kind of show that seems destined for a dedicated YouTube life. My favorite genuine moment is the small conversation Purity has with Betty Bossy before she checks into her therapist’s office. It’s slow and develops Betty’s character effectively in small strokes, discussing her life decisions and corrections. It was the moment in Pure O where the characters onscreen felt like living, breathing people and done with a degree of subtlety. The fact that everyone else mocks Betty is just another indication of their general flippancy.

There are many merits to Pure O. The acting is fairly good throughout and Stella Singer (Choices) is an excellent choice as a lead. She has great moments. Her character is very passive for the majority of the short film, either being talked to or keeping the intruding voices/thoughts at bay, which causes her to feel like a passenger too often. Singer has such a striking, expressive face (seriously, she looks so different with her hair up versus down) that I wanted her to have more opportunities to stretch her acting muscles. It may be fresh in my mind, but she reminded me of Lola Kirke (Gemini). This is a professional looking and edited short film. Even the opening concert scene impressed me with how it was able to tie together an effective looking stage experience. The 90s aesthetic feels very gamely committed, none more so than in wardrobe where each character almost feels entirely defined by a color or extreme look. The strict adherence to stylized costuming does a smart job of telling you about the characters in visual ways, already cuing you without wasting precious time. The sound design is excellent, with the collage of negative voices crashing against her brain like the oncoming surf. The line, “It all went to hell after Karen Carpenter pierced her clit,” is a wonderful non-sequitur that took my breath away. The strange humor of a low-budget public access TV talk show was amusingly absurdist, complete with talking pine tree sidekick and break dancing robot. It’s the kind of show that seems destined for a dedicated YouTube life. My favorite genuine moment is the small conversation Purity has with Betty Bossy before she checks into her therapist’s office. It’s slow and develops Betty’s character effectively in small strokes, discussing her life decisions and corrections. It was the moment in Pure O where the characters onscreen felt like living, breathing people and done with a degree of subtlety. The fact that everyone else mocks Betty is just another indication of their general flippancy.

Pure O is a well-intentioned short film with fine attributes, both in technical matters and with its troupe of actors, notably the compelling lead heroine, Stella Singer. The variety of supporting characters will keep you watching since it’s something new every few minutes; however, the glut of characters also detracts from the drive of the story and its aim toward Purity learning to accept her mental illness. The inconsistent tone also poses as a distraction from the narrative goals, making the serious stuff feel less serious and the comic asides feel like they’ve been retrofitted from another project. This marriage of tone could have worked, but this calibration doesn’t quite get there. I do think people can get entertainment from Pure O (after all, the time investment is pretty accessible). It feels like a glimpse of a larger story, one worth developing into a tighter, character-driven plot with less wacky side diversions. Still, congratulations to the many talented people who pooled their efforts and brought a short film into life. Pure O is an intriguing yet flawed start to a character and a world worth further exploration. But if this is all we get, at least there was a break dancing robot to go with my Karen Carpenter pierced clitoris aside.

Pure O is a well-intentioned short film with fine attributes, both in technical matters and with its troupe of actors, notably the compelling lead heroine, Stella Singer. The variety of supporting characters will keep you watching since it’s something new every few minutes; however, the glut of characters also detracts from the drive of the story and its aim toward Purity learning to accept her mental illness. The inconsistent tone also poses as a distraction from the narrative goals, making the serious stuff feel less serious and the comic asides feel like they’ve been retrofitted from another project. This marriage of tone could have worked, but this calibration doesn’t quite get there. I do think people can get entertainment from Pure O (after all, the time investment is pretty accessible). It feels like a glimpse of a larger story, one worth developing into a tighter, character-driven plot with less wacky side diversions. Still, congratulations to the many talented people who pooled their efforts and brought a short film into life. Pure O is an intriguing yet flawed start to a character and a world worth further exploration. But if this is all we get, at least there was a break dancing robot to go with my Karen Carpenter pierced clitoris aside.

Nate’s Grade: C+

You must be logged in to post a comment.