Blog Archives

Joker: Folie à Deux (2024)

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think actually work as musicals.

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think actually work as musicals.

Joker 2, which I will be referring to it as for the duration of this review mostly because I don’t want to type out Folie a Deux, and not due to some explicit dislike of the French, is a fascinating misfire that comes across as downright disdainful of its audience, its studio, and its very existence. The last time I felt this way from a sequel was 2021’s Matrix Resurrections, another fitfully contemptuous movie that was alienating and self-erasing and also from Warner Brothers. The first Joker movie in 2019 was a surprise hit, grossing over a billion dollars, which meant that the studio wasn’t going to sit idly by and not force a sequel for a movie clearly intended to be one complete movie. While the first movie cost a modest $50 million, the sequel cost close to $200 million, with big pay days for Joaquin Phoenix, Lady Gaga, and co-writer/director Todd Phillips, who I have to remind you, dear reader, was actually nominated for a Best Director Oscar in 2019. Having gotten their paydays, it feels like Phillips and his collaborators have set out to scorch all available earth, going so far as to even insult fans of the earlier movie. Add the bizarre musical factor, and I don’t know how else to describe Joker 2 but as an alienating and miserable protracted exercise in self-immolating artistic hubris. It’s so rare to see this level of artistic clout used to proverbially stick a finger in the eye of every fan and studio exec who might have hoped there could be something of value here.

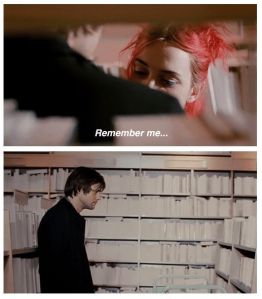

Let’s tackle the plot first, as we pick up months after the events of the 2019 film where lowly Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) is being tried for the murders he committed, most famously on a TV talk show where he debuted his stand-up comedian persona as Joker in full regalia. There’s an (un)healthy contingent of the rabble that idolize Arthur, finding the Joker to be some kind of mythic hero of class-conscious revolution, pointing out how society is failing all the little guys getting crushed by the rich and powerful and privileged, like that dead Wayne family. One of those fans is Lee (Gaga), a.k.a. Harleen Quinzel, a disturbed young woman obsessed with getting closer to Arthur, and he is extremely appreciative of the fawning attention. The defense case hinges upon whether or not Arthur was acting on his own accord or had a psychotic break, disassociating as “Joker,” and thus cannot be held accountable for the murders. Except it seems “Joker” is all the people of Gotham want to talk about, whether it’s the media or the public, and what about poor lonely Arthur?

Let’s tackle the plot first, as we pick up months after the events of the 2019 film where lowly Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) is being tried for the murders he committed, most famously on a TV talk show where he debuted his stand-up comedian persona as Joker in full regalia. There’s an (un)healthy contingent of the rabble that idolize Arthur, finding the Joker to be some kind of mythic hero of class-conscious revolution, pointing out how society is failing all the little guys getting crushed by the rich and powerful and privileged, like that dead Wayne family. One of those fans is Lee (Gaga), a.k.a. Harleen Quinzel, a disturbed young woman obsessed with getting closer to Arthur, and he is extremely appreciative of the fawning attention. The defense case hinges upon whether or not Arthur was acting on his own accord or had a psychotic break, disassociating as “Joker,” and thus cannot be held accountable for the murders. Except it seems “Joker” is all the people of Gotham want to talk about, whether it’s the media or the public, and what about poor lonely Arthur?

If I had to fathom a larger thematic point, it feels like Phillips is trying to put our media ecosphere and comics fandom into judgement. He’s pointing to his movie and saying, “You wouldn’t have cared nearly as much about this project had it just been some other spooky, disturbed man losing his sanity and lashing out. You only care because he would eventually become the notorious Batman villain or lore, and that’s why you’re back.” Well, to answer succinctly, of course. When your movie’s conceptual conceit is all about providing a gritty back-story for a famous supervillain, don’t be surprised when there’s more attention and interest. This would be the same if Phillips had made a searing drama about teenage nihilism and easy access to guns and then called it Dylan Klebold: The Movie (one half of the Columbine killers, if you forgot). Stripping back layers to provide setup for a famous killer will always generate more interest than if it was some fictional nobody. It’s an accessible starting point for a viewer and there’s an innate intrigue in trying to answer the tantalizing puzzle of how terrible people got to be so terrible.

I found the 2019 movie to be a mostly interesting experiment without too much to say with its larger social commentary. It felt like Phillips relied a bit too heavily on that assumed familiarity with the character to fill in the missing gaps of his storytelling. It was a proof of concept for that proved successful beyond measure (a billion dollars, 11 Oscar nominations, including THREE for Phillips). This time, Phillips is taking even less subtlety with his blowtorch as he actively annihilates whatever audiences may have enjoyed or appreciated in the first movie.

And in order to fully appreciate the scope of this movie’s active distaste for its own existence, I’ll be treading into some major spoilers, so jump forward a paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled, dear reader. The conclusion of this sequel is a miserable succession of hits that degrades Arthur. At the conclusion of the 2019 original, at least you could say he was becoming a more realized version of what he wanted to be, albeit a disturbed murderer, but one who became the face of a revolution and gained a legion of adoring followers that he desperately craved. At the end of Joker 2, Arthur pathetically admits in his trial there is no alternate Joker persona and that he’s just a sad loser. Then Lee admits that she was only ever interested in “Joker” and wants nothing to do with Arthur the sad loser. And then upon returning to prison, another inmate confronts Arthur, apparently feeling personally betrayed for whatever reason. This irate prisoner stabs Arthur to death and then laughs in a corner, slicing a smile into the sides of his mouth, Heath Ledger-style. The movie literally ends with Arthur laying in a pool of his own blood, staring dead-eyed into the camera, with Phillips metaphorically painting emphatically at his corpse and defiantly saying, “Look, he’s not even the Joker now! Do you still care? Do you?” These movies were designed to be the untold history of the man who would be Joker, and they now have ended up being four hours about the guy whose idea maybe inspired a criminal lunatic to improve upon what he felt was another guy’s brand. What’s even the point? We followed two movies about the guy who isn’t the Joker? Seems pretty definitive there won’t be a third Arthur Fleck movie, as there’s nothing left for Phillips and his anarchic collaborators to demolish to smithereens.

And in order to fully appreciate the scope of this movie’s active distaste for its own existence, I’ll be treading into some major spoilers, so jump forward a paragraph if you wish to remain unspoiled, dear reader. The conclusion of this sequel is a miserable succession of hits that degrades Arthur. At the conclusion of the 2019 original, at least you could say he was becoming a more realized version of what he wanted to be, albeit a disturbed murderer, but one who became the face of a revolution and gained a legion of adoring followers that he desperately craved. At the end of Joker 2, Arthur pathetically admits in his trial there is no alternate Joker persona and that he’s just a sad loser. Then Lee admits that she was only ever interested in “Joker” and wants nothing to do with Arthur the sad loser. And then upon returning to prison, another inmate confronts Arthur, apparently feeling personally betrayed for whatever reason. This irate prisoner stabs Arthur to death and then laughs in a corner, slicing a smile into the sides of his mouth, Heath Ledger-style. The movie literally ends with Arthur laying in a pool of his own blood, staring dead-eyed into the camera, with Phillips metaphorically painting emphatically at his corpse and defiantly saying, “Look, he’s not even the Joker now! Do you still care? Do you?” These movies were designed to be the untold history of the man who would be Joker, and they now have ended up being four hours about the guy whose idea maybe inspired a criminal lunatic to improve upon what he felt was another guy’s brand. What’s even the point? We followed two movies about the guy who isn’t the Joker? Seems pretty definitive there won’t be a third Arthur Fleck movie, as there’s nothing left for Phillips and his anarchic collaborators to demolish to smithereens.

When I heard that Joker 2 was going to be a musical, I actually got a little excited, as it felt like Phillips was going to try something very different. Now the curse of many modern movie musicals is trying to come up with an excuse for why the world is exploding in song and dance, like 2002’s Chicago implying it’s all in Roxy’s vivid imagination. Joker 2 takes a similar approach, conveying that when Arthur is breaking out into song that it’s a mental escape for him, that it’s not actually happening in his literal reality. Except… why are there sequences outside Arthur’s point of view where other characters are breaking into song, notably Lee? Is this perhaps a transference of Arthur’s perspective, like he’s imagining them on the outside joining him in tandem? The concept fits with his desperate desire to forge meaningful human connections with people that see him for who he is, and having another character harmonize with him provides a fantasy of validation. Except… there’s no meaningful personal connection between Arthur and the allure of movie musicals. It’s not like he or his domineering mother, the same woman he murdered if you recall, were lifelong fans of musicals and their magical possibilities. It’s not like 2001’s Dancer in the Dark where our lonely protagonist dreamed of being in a movie musical as an escape from her depressing life of exploitation and poverty. It just happens, and you’re listening to Phoenix’s off-putting, gravelly voice straining to recreate classics like “For Once in My Life” and “When You’re Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With You).” It’s also a criminal waste of a perfectly game Gaga.

Phillips’ staging of his musical numbers are so lifelessly devoid of energy and imagination. Most of our musical numbers are merely in the same setting without any changes besides now one, or occasionally two, characters are singing. There’s one number that becomes a dance atop a roof, and several duets that appear like a hammy Sonny and Cher 1970s variety TV show, and that’s all you’re getting folks in the realm of visual escapism and choreography. In retrospect, it feels like the musical aspect of the sequel might have been a manner to pad it to feature-length, adding 16 performances and over 40 minutes of singing old standards. There’s a good deal of repetition with this sequel, as much of the plot is restating the events of the first film; that’s essentially what the courtroom drama facilitates as it trots out all the previous characters to recap their roles and point an accusatory finger back at Arthur.

Phillips’ staging of his musical numbers are so lifelessly devoid of energy and imagination. Most of our musical numbers are merely in the same setting without any changes besides now one, or occasionally two, characters are singing. There’s one number that becomes a dance atop a roof, and several duets that appear like a hammy Sonny and Cher 1970s variety TV show, and that’s all you’re getting folks in the realm of visual escapism and choreography. In retrospect, it feels like the musical aspect of the sequel might have been a manner to pad it to feature-length, adding 16 performances and over 40 minutes of singing old standards. There’s a good deal of repetition with this sequel, as much of the plot is restating the events of the first film; that’s essentially what the courtroom drama facilitates as it trots out all the previous characters to recap their roles and point an accusatory finger back at Arthur.

There is one lone outstanding scene in Joker 2, and it happens to be when Arthur, in full Joker makeup, is cross-examining his old clown entertainer work buddy, Gary Puddles (Leigh Gill). Arthur admonishes Gary, saying he spared him, and Gary painfully articulates how hellish his life has been as witness to Arthur’s killing, how little he sleeps, how it torments him and makes him so afraid. For a brief moment, this character shares his vulnerability and the lingering trauma that Arthur has inflicted, and it appears like Arthur is wounded by this realization, until he settles back into the persona he’s trying to put forward, the “face” for his defense, and goes back to ridiculing Gary’s name and turning the cross-examination into an awkward standup session. It’s a palpable moment that feels raw and surprising and empathetic in a way the rest of the movie fails to.

Is there anything else to celebrate with Joker 2’s troubled existence? The cinematography by Lawrence Sher can be strikingly beautiful, especially with certain shot compositions and lighting contrasts. It makes it all the more confounding when almost all the musical numbers lack visual panache. The Oscar-winning composer returns and while still atmospheric and murky the score is also far less memorable and fades too often into the background, like too many of the technical elements. Joker 2 has plenty of talented people involved in front of and behind the camera, but to what end? What are all their troubles adding up to? It practically feels like a very expensive practical joke, on the audience, on the studio, and that is genuinely fascinating. However, it doesn’t make the end product any better, and the film’s transparent contempt sours every minute of action. Even if you were a super fan of Joker or morbidly curious, steer clear of Folie a Deux, a folly on all of us.

Nate’s Grade: D

It Ends With Us (2024)

If you’re expecting a charming romantic drama about a young woman moving back home and finding new love and rekindling romance with a past love, then you might be better off scanning the Hallmark Channel. For those blissfully unfamiliar with author Colleen Hoover, It Ends With Us is her best-seller about domestic abuse. The Dickensian-named Lily Bloom (Blake Lively), who wants to open a flower store, comes back home after her abusive father passes, and she reconnects with Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Sklenar), her childhood love who her father chased away. She also falls for child neurosurgeon Ryle Kincaid (director Justin Baldoni) who happens to be an abuser. It takes an hour into the movie before Ryle physically harms Lily, which means the movie up until that point is paced and structured like a typical romantic drama and we’re meant to find him smooth and desirable. Perhaps Hoover and the filmmakers are trying to better place us in the position of the abused spouse, providing context that some might use to excuse toxic behavior and red flags, but if they wanted to set up more of a love triangle, they’ve done a poor job. Atlas mostly appears in flashbacks as the idealistic, impoverished boyfriend she kind of takes in. He then re-establishes himself in the present with a successful fancy restaurant, and the movie more or less just puts him on a shelf and says, “When she’s ready to have someone nice, she’ll settle back with that bland guy from her past.” Feels like we’re spending too much time on stories that we shouldn’t, and less time on ones we should. It’s grandiose soap opera plotting for serious subject matter. Credit director/co-star Baldoni for not soft-pedaling the treacherous nature of his character’s control and insecurity. There’s a great deal of very uncomfortable and disturbing abuse sequences, including a rape, for a PG-13 movie. Domestic abuse, and growing up in the shadow of domestic abuse, makes for some very challenging viewing. If the movie was more insightful, or honest, or even nuanced, it might be worth enduring the discomfort of its two hours. It’s not. It’s just punishing.

If you’re expecting a charming romantic drama about a young woman moving back home and finding new love and rekindling romance with a past love, then you might be better off scanning the Hallmark Channel. For those blissfully unfamiliar with author Colleen Hoover, It Ends With Us is her best-seller about domestic abuse. The Dickensian-named Lily Bloom (Blake Lively), who wants to open a flower store, comes back home after her abusive father passes, and she reconnects with Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Sklenar), her childhood love who her father chased away. She also falls for child neurosurgeon Ryle Kincaid (director Justin Baldoni) who happens to be an abuser. It takes an hour into the movie before Ryle physically harms Lily, which means the movie up until that point is paced and structured like a typical romantic drama and we’re meant to find him smooth and desirable. Perhaps Hoover and the filmmakers are trying to better place us in the position of the abused spouse, providing context that some might use to excuse toxic behavior and red flags, but if they wanted to set up more of a love triangle, they’ve done a poor job. Atlas mostly appears in flashbacks as the idealistic, impoverished boyfriend she kind of takes in. He then re-establishes himself in the present with a successful fancy restaurant, and the movie more or less just puts him on a shelf and says, “When she’s ready to have someone nice, she’ll settle back with that bland guy from her past.” Feels like we’re spending too much time on stories that we shouldn’t, and less time on ones we should. It’s grandiose soap opera plotting for serious subject matter. Credit director/co-star Baldoni for not soft-pedaling the treacherous nature of his character’s control and insecurity. There’s a great deal of very uncomfortable and disturbing abuse sequences, including a rape, for a PG-13 movie. Domestic abuse, and growing up in the shadow of domestic abuse, makes for some very challenging viewing. If the movie was more insightful, or honest, or even nuanced, it might be worth enduring the discomfort of its two hours. It’s not. It’s just punishing.

Nate’s Grade: D

Uglies (2024)

Even though Uglies is based upon a book series that hails back to 2005, it feels so much like it was developed in a vat subsisting on the runny discharge from other YA dystopian projects, finally settling into an unappealing mixture of familiar tropes. In this post-apocalyptic future world, society has rebuilt itself with a caste system that celebrates beauty. Teenagers undergo surgical operations and brainwashing to make themselves a member of the Pretties, the cool kids. If you’re even remotely familiar with YA storytelling, you can likely guess exactly where the movie goes from here. Our heroine is called Squint because society seems to think her eyes need work. There’s another character named Nose for the same reason, meaning that upon birth, I guess the doctor just holds up you baby and starts verbally roasting them. Squint is played by Netflix staple Joey King (The Kissing Booth, A Family Affair) and therein lies one of our central adaptation problems. The rules of Hollywood will not allow unattractive lead actors in movies like this, so the filmmakers give her brunette hair and less makeup, as if we’re supposed to find movie star Joey King to be naturally hideous. It’s the same with every actor in the movie. Now, if you were going to adapt this to a visual medium, maybe you lean into the visual contrasts in a more specific manner: all the “Uglies” are minorities and all the “Pretties” are lighter-skinned or white. That would bring an added colorism commentary but it would also be steering the movie into a more dangerous relevancy. The plot is all simplistic high school battle lines about individualism versus conformity, self-acceptance versus assimilation, though the optics of having a trans woman (Laverne Cox) being the evil head of education forcing surgery on teens and brainwashing them feels quite problematic considering grotesque conservative theories endangering the lives of actual trans people. There is one surprise in Uglies, one that I’ll spoil for you, dear reader. It doesn’t end. It sets up the next adventure with Squint supposedly bringing down the corrupt society from the inside, but I challenge anyone not familiar with the book series to be that compelled to put right the unresolved storylines and character arcs from this stalled launch.

Nate’s Grade: C-

Challengers (2024)

The sweaty, sexy indie hit from the spring is about a tennis throuple told over the course of one pivotal match, where our two male athletes are at very different points in their careers and the woman who came between them. Patrick (Josh O’Conner) and Art (Mike Faist) are the best of friends when they started on the tennis circuit with dreams of making the big tournaments. They both set their sights on Tashi (Zendaya), a tennis phenom since her teenage years who is starting to reach her prime. The movie bounces back and forward through time (like a tennis ball!) to chart the changing relationships between the three, as we’re left to pick up the pieces as to what happened, who fell for who, who broke up with who, and how it relates to the central battle of wills playing out in the present-day match. The best part of Challengers are its characters and ever-shifting power dynamics, which makes each scene rich to digest and examine, especially once Tashi’s career takes an unexpected turn. Director Luca Guadagnino (Bones and All, Call Me By Your Name) keeps things lively with plenty of style including exercising every POV imaginable from the floor, to a tennis balls, and the players with racket banging in hand. We might have gotten a POV from a passing bird had it only gone longer. The movie is electrified by a pulse-pounding score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, a propulsive energy that reminded me of the similar service of the Run Lola Run soundtrack. What holds back the film for me is that the last act is dragged out and it culminates in an ending that is the most obvious as well as underwhelming, which makes the extended dragging even more ultimately tedious. The acting is good all around with each member getting to experience a high-point and low-point of their career and personal lives. However, it’s really Art and Tashi’s movie as Patrick serves as an elevated supporting role. And for a movie with such heat and hype, I guess I was expecting a little more action, if you will. Challengers is an intriguing, entertaining, and refreshingly adult sports drama that I wish had, forgive me, some more balls.

The sweaty, sexy indie hit from the spring is about a tennis throuple told over the course of one pivotal match, where our two male athletes are at very different points in their careers and the woman who came between them. Patrick (Josh O’Conner) and Art (Mike Faist) are the best of friends when they started on the tennis circuit with dreams of making the big tournaments. They both set their sights on Tashi (Zendaya), a tennis phenom since her teenage years who is starting to reach her prime. The movie bounces back and forward through time (like a tennis ball!) to chart the changing relationships between the three, as we’re left to pick up the pieces as to what happened, who fell for who, who broke up with who, and how it relates to the central battle of wills playing out in the present-day match. The best part of Challengers are its characters and ever-shifting power dynamics, which makes each scene rich to digest and examine, especially once Tashi’s career takes an unexpected turn. Director Luca Guadagnino (Bones and All, Call Me By Your Name) keeps things lively with plenty of style including exercising every POV imaginable from the floor, to a tennis balls, and the players with racket banging in hand. We might have gotten a POV from a passing bird had it only gone longer. The movie is electrified by a pulse-pounding score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, a propulsive energy that reminded me of the similar service of the Run Lola Run soundtrack. What holds back the film for me is that the last act is dragged out and it culminates in an ending that is the most obvious as well as underwhelming, which makes the extended dragging even more ultimately tedious. The acting is good all around with each member getting to experience a high-point and low-point of their career and personal lives. However, it’s really Art and Tashi’s movie as Patrick serves as an elevated supporting role. And for a movie with such heat and hype, I guess I was expecting a little more action, if you will. Challengers is an intriguing, entertaining, and refreshingly adult sports drama that I wish had, forgive me, some more balls.

Nate’s Grade: B

Garden State (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

Andrew Large Largeman (Braff) is an out-of-work actor living in an anti-depressant haze in LA. He heads back to his old stomping grounds in New Jersey when he learns that his mother has recently died. Andrew has to reface his psychiatrist father (Ian Holm), the source of his guilt and prescribed numbness. He has forgotten his lithium for his trip, and the consequences allow Andrew to begin to awaken as a human being once more. He meets old friends, including Mark (Peter Sarsgaard), who now digs graves for a living and robs them when he can. He parties at the mansion of a friend made rich by the invention of silent Velcro. Things really get moving when Andrew meets Sam (Natalie Portman), a free spirit who has trouble telling the truth and staying still. Their budding relationship coalesces with Andrews re-connection to friends, family, and the joys life can offer.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff deserves a medal for finally coaxing out the actress in Portman. She herself has looked like an overly medicated, numb being in several of her recent films (Star Wars prequels, I’m looking in your direction), but with her plucky, whimsical role in Garden State, Portman proves that her careers acting apex wasn’t in 1994’s The Professional when she was 12. Her winsome performance gives Garden State its spark, and the sincere romance between Sam and Andrew gives it its heart.

Sarsgaard is fast becoming one of the best young character actors out there. After solid efforts in Boys Don’t Cry and Shattered Glass, he shines as a coarse but affectionate grave robber that serves as Andrew’s motivational elbow-in-the-ribs. Only the great Holm seems to disappoint with a rare stilted and vacant performance. This can be mostly blamed on Braff’s underdevelopment of the father role. Even Method Man pops up in a very amusing cameo.

The humor in Garden State truly blossoms. There are several outrageous moments and wonderfully peculiar characters, but their interaction and friction are what provide the biggest laughs. So while Braff may shoehorn in a frisky seeing-eye canine, a knight of the breakfast table, and a keeper of an ark, the audience gets its real chuckles from the characters and not the bizarre scenarios. Garden State has several wonderfully hilarious moments, and its sharp sense of humor directly attributes to its high entertainment value. The film also has some insightful looks at family life, guilt, romance, human connection, and acceptance. Garden State can cut close like a surgeon but it’s the surprisingly elegant tenderness that will resonate most with a crowd.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Garden State is not a flawless first entry for Braff. It really is more a string of amusing anecdotes than an actual plot. The film’s aloof charm seems to be intended to cover over the cracks in its narrative. Braff’s film never ceases to be amusing, and it does have a warm likeability to it; nevertheless, it also loses some of its visual and emotional insights by the second half. Braff spends too much time on less essential moments, like the all-day trip by Mark that ends in a heavy-handed metaphor with an abyss. The emotional confrontation between father and son feels more like a baby step than a climax. Braff’s characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.

Garden State is a movie thats richly comic, sweetly post-adolescent, and defiantly different. Braff reveals himself to be a talent both behind the camera and in front of it, and possesses an every-man quality of humility, observation, and warmth that could soon shoot him to Hollywood’s A-list. His film will speak to many, and its message about experiencing lifes pleasures and pains, as long as you are experiencing life, is uplifting enough that you may leave the theater floating on air. Garden State is a breezy, heartwarming look at New York’s armpit and the spirited inhabitants that call it home. Braff delivers a blast of fresh air during the summer blahs.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

In the summer of 2024, there were two indie movies that defined the next years of your existence. If you were under 18, it was Napoleon Dynamite. If you were between 18 and 30, it was Garden State. Zack Braff’s debut as writer/director became a Millennial staple on DVD shelves, and I think at one time it might have been the law that everyone had to own the popular Grammy-winning soundtrack. It wasn’t just an indie hit, earning $35 million on a minimal budget of $2.5 million; it was a Real Big Deal, with big-hearted young people finding solace in its tale of self-discovery and shaking loose from jaded emotional malaise. If you had to determine a list of the most vital Millennial films, not necessarily on quality but on popularity and connection to the zeitgeist, then Garden State must be included. Twenty years later, it’s another artifact of its time, hard to fully square outside of that influential period. It’s a coming-of-age tale wrapped up in about every quirky indie trope of its era, including a chief example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, even though that term was first coined from the AV Club review of 2005’s Elizabethtown. Twenty years later, Garden State still has some warm fuzzies but loses its feels.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Natalie Portman had been an actress that I was more cool over until 2004 with the double-whammy of Garden State and her Oscar-nominated turn in Closer. She’s since become one of the most exciting actors who goes for broke in her performances whether they might work or not. In 2004, I thought her performance in Garden State was an awakening for her, and in 2024 it now feels so starkly pastiche. Bless her heart, but Portman is just calibrated for the wrong kind of movie. Her energy level is two to three times that of the rest of the movie, and while you can say she’s the spark plug of the film, the jolt meant to shake Andrew awake, her character comes across more as an overwritten cry for help. Sam is even more prototypical Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) than Kirsten Dunst’s bouncy character in Elizabethtown. Her entire existence is meant to provoke change upon our male character. This in itself is not an unreasonable fault; many characters in numerous stories are meant to represent a character’s emotional state. It’s just that there isn’t much to Sam besides a grab-bag of quirky characteristics: she’s a compulsive liar, though nothing is ever really done with this being a challenge to building lasting bonds; she’s incapable of keeping pets alive, and Andrew could be just another pet; she’s consumed with being unique to the point of having to stand up and blurt out nonsense words to convince herself that nobody in human history has duplicated her recent combination of sounds and body gestures, but she’s all archetype. She exists to push Andrew along on his reawakening, including introducing him and us to The Shins (“This song will change your life”). She’s entertaining, and Portman is charming, but it’s an example of trying so hard. I thought her cheeks must have hurt from holding a smile so long. I’m sure Braff would compare Sam to Annie Hall, as Diane Keaton was perhaps the mold for the MPDG, except she more than stood on her own and didn’t need a nebbish man to complete her.

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

Admittedly, that soundtrack is still a banger. It soars when it needs to, like Imogen Heep’s “Let Go” over the race-back-to-the-girl finale, and it’s deftly somber when it needs to, like Iron and Wine’s cover of “Such Great Heights” and “The Only Living Boy in New York” paired with our big movie kiss. It’s such a cohesive, thematic whole that lathers over the exposed seams of the movie’s scenic hodgepodge. Braff tried to find similar magic with his musical choices for 2006’s The Last Kiss, a movie he starred in but did not direct (he also provided un-credited rewrites to Paul Haggis’ adapted screenplay). That soundtrack is likewise packed with eclectic artists (he even snags Aimee Mann) but failed to resonate like Garden State. It’s probably because nobody saw the movie and Braff’s character was, as I described in my 2006 review, an overgrown man-child afraid his life lacks “surprises” now that he was going to be a father. Sheesh.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Re-View Grade: C+

Hit Man (2024)

Hit Man is a movie that is wonderfully hard to describe. The premise has an easy-to-grasp hook that promises fun and hijinks, but where it goes from there takes on as many transformations as its protagonist, Gary Johnson (Glen Powell). It transforms from a fun game of undercover conning with wigs and silly accents into an unexpected rom-com hinging upon mistaken identity, maintaining assumed appearances, and secrets that then transforms into full film noir without losing its unique identity and the stakes of the character relationships. If you’d expect any filmmaker to pull off that trick, writer/director Richard Linklater has to be one of the best to keep things running smoothly, and that he does, as Hit Man is a crowd-pleasing comedy with some unexpected directions to keep everyone guessing until it lands on its own morally gray terms.

The movie is also, chiefly, a showcase of star and co-writer Powell, a handsome young actor hitting a new ascent of his career with last year’s Anyone But You and the upcoming Twisters. Powell is probably best known as the smirking guy you loved to hate in Top Gun: Maverick, but he’s also played memorable supporting roles in Scream Queens and three other Linklater film projects, notably 2016’s Everybody Wants Some!!, a pseudo-spiritual sequel to the seminal Dazed and Confused. This is Powell’s acting showcase and he’s utterly terrific. He has great infectious fun getting into the various hitman characters, which mostly exist in montages, and trying on different personas and voices. I cackled when he was doing his impression of Christian Bale’s Patrick Bateman, and I smiled throughout most of the other personas. It’s easy to see the network TV version of this premise, where every week Gary adopts a new persona and disguise to bust the next possible criminal from hiring a hitman, like an edgier Quantum Leap). The culprits are played like nitwits but then again the police are also played as nitwits (are there THIS many attempted hitman hirings in one city for the police to have a full-time unit?).

But before this acting experiment can get too broad or too redundant, Linklater and Powell switch things up. Around the Act One break is where Gary meets Madison (Adria Arjona), and that’s when everything changes for him and the audience. Now we have emotional stakes, because Gary intervenes to save Madison. While the circumstances of their first meeting involve her wanting to kill her husband and believing Gary as the professional to do such a job, the scene plays as a disarming first date you’d find in another charming romantic comedy, where it’s clear to anyone with a pulse that these two have something together. Instead of busting her for the solicitation, he pushes her to change her mind, take the money and leave her no-good husband rather than finding a questionable man to eliminate him. From there, they form a romantic relationship that fluctuates wildly. She thinks Gary is “Ron,” the suave and confidant persona Gary adopted for their sit-down. So the nerdy tech nerd who teaches philosophy must pretend to be the daring and dangerous man of mystery he wishes he could be. The script doesn’t get carried away with its farcical elements in play, juggling multiple identities for multiple specific audiences, but it asks the question, “Why can’t the milquetoast Gary simply be Ron? Is this an unexpected means of self-actualization for the nerd to win the girl?” Through this extreme exercise, Gary can mold himself into the man he would like to be. The rom-com is flirty, funny, and just as enjoyable as the earlier wacky comedy of being a versatile master of disguise.

It also really helps things when your two lead actors have such strong chemistry. Powell and Arjona (Father of the Bride, Andor) are smoldering together, like full on “get a room already” territory. This lends even more credence when Hit Man makes its next transformation into film noir thriller. I won’t divulge the specific plot elements but it all works with what Linklater has already established. There’s trouble for the both of them, and the question becomes how far is each participant willing to go to stay above the fray. The transition from silly costume comedy to sundry noir thriller is handled so naturally, as if the characters, already existing under such unique circumstances, found themselves in the elevated movie-movie version of their crazy relationship. Rather than feel contrived, Linklater and Powell have put in the work to make these twists and turns credible and exciting. The shifting nature of the movie is a wonderful reflection of its fake hitman hero. There’s a scene late in the film, where all of our principal players have come together, and you have characters saying one thing, intimating another, for different versions of different audiences, and it’s such a masterful tonal dance that feels satisfying as a climactic turning point as well as genuinely impressive for all the myriad subtext in play.

This is a clear-cut case of a movie being “inspired by” a true story rather than being “based on” a true story. Generally, we expect the “based on” stories to have some voracity to reality. We accept that there will be alterations for dramatic purposes, externalizing the internal, condensing timelines and characters into a more accessible structure, etc. If you go to a movie about Jackie Robinson, you don’t expect to see the famous baseball slugger fighting space monsters (“Racism was the real giant monster all along”). Hit Man is based upon a 2001 long-form news article by Texas Monthly journalist Skip Hollandsworth, the same author of the source material for Linklater’s fascinating true crime dark comedy gem, 2011’s Bernie, which I highly recommend (a career-best Jack Black). The real Gary Johnson really did pose as a fake hitman for the purposes of catching real criminals, but the rest of the movie exists in its own fictional universe of dramatic complications. Usually we want our film stories to have more fidelity with the truth and reality, but I’m glad Linklater and Powell recognized the sheer storytelling potential of this quirky premise. Sticking to the facts could have told an amusing story, but feeling confident to take bold leaps with well-worn genre motifs, when called for, is the right call for making the most of this tale.

The shame of Hit Man is how quickly it will likely be subsumed by Netflix’s suffocating tidal waves of content. Here is a fun, likable, and surprising indie comedy with definite mass appeal buoyed by great performances, clever writing, and a tonally shifting narrative to keep things fresh. Powell gets the breakout showcase he deserves and we get one of the most unexpected and amusing rom-coms of recent years. Hit Man is a movie that deserves to be seen, to be enjoyed with a crowd, but I worry it will get lost in the shuffle of streaming titles. I suppose this might just be the current reality for fans of mid-level adult dramas and comedies. At least they have a home on the streaming networks even if these movies would have been theatrical breakouts years ago. Regardless, Hit Man is a good time with good people pretending to be bad, or is it bad people pretending to be good, but whatever pretense, it’s a charming winner worth your two hours.

Nate’s Grade: B+

The Idea of You/ Turtles All the Way Down (2024)

The Idea of You is the kind of movie that Hollywood used to crank out, a romantic drama star vehicle based upon a popular novel and with a skilled director, and now it forgoes any theatrical run and ends up as another option on a streaming channel. The Idea of You follows a 40-year-old divorced single mom played by Anne Hathaway who also happens to run an L.A. art gallery and has a meet-cute with a handsome boy band member (Nicholas Galitzine, Purple Hearts) at the Coachella music festival (oh the magic lives of people never having to worry about bills in rom-coms). they hit it off, and the rest of the movie is whether or not they can make a romance work. There’s a 15-year age gap that she feels very self-conscious about as an older woman (“older” by Hollywood standards). She’s this formerly normal woman who wants to date one of the most famous music stars in the world who isn’t always available, but most of the problems and conflicts stem from the perceived issues of the age gap. It’s a charming romance that’s more dramatic than it is comedic, and Hathaway is quite good as our lead plucked from obscurity. Though the many scenes of our smitten boy band member making googly eyes at Hathaway as he reminds her how attractive she is, and as she bashfully demurs, are a little much (it’s Anne Hathaway, notorious horrible-looking human specimen, right?). As a core romance, the movie works well under the guidance of director and co-writer Michael Showalter (The Big Sick), and it’s more adult than I was expecting. It’s rated R for language and it’s also more sensual, but it’s also more adult as in looking at the ramifications of this relationship in a mature perspective, from the terrors of paparazzi imposition to her daughter being harassed at school. The portrayal is thus more engaging and engrossing and feels above the more flippant and flimsy romances that would settle for far less. Though be warned: there are several sequences of singing and serenading which might cause you to shrink awkwardly inward on your couch. Surprisingly thoughtful, and relatively romantic, The Idea of You is a charming reminder of the appeal of comforting tales of love blossoming in unexpected places and pretty people allowing themselves the choice to be happy.

Based on best-selling YA author John Green’s 2017 novel, Turtles All the Way Down is a very accessible and very affecting glimpse at living with mental illness, obsessive compulsive disorder, and intrusive thoughts. Aza (Isabela Merced) has an overwhelming inner monologue that sabotages her daily life in high school and carries her along anxious thought diversions, constantly relating to some illness growing inside her that she needs to cleanse. This is the crux of the story, along with her relationship with her super eager best friend. There’s a romantic side plot where she helps out a rich classmate whose billionaire dad has gone missing, which feels like a plot device to necessitate the two characters spending time together. The standout aspect of this adaptation by writer/director Hannah Marks (Don’t Make Me Go) is its unsparing and honest yet hopeful depiction of mental health and intrusive thoughts. Merced (Dora and the Lost City of Gold, Madame Web) is excellent and deeply empathetic as this woman held hostage by her wayward thoughts and impulses. It’s a performance that goes beyond easy depictions of aloof detachment or exaggerated histrionics, shedding any acting techniques that are too mannered or attention-seeking. Marks’ direction helps reflect Aza’s troubled mind with rapid insert edits and voice over to communicate the intrusive thoughts and maelstrom of spiraling negative emotions. If you’re a fan of Green’s popular novels, or YA-themed literature, or even just honest attempts to empathize with teens in turmoil, then Turtles All the Way Down is worth battling through any negative thoughts to finish and relish the journey.

Nate’s Grades:

The Idea of You: B

Turtles All the Way Down: B+

The Fall Guy (2024)

The Fall Guy, loosely based upon the 1980s TV series starring Lee Majors, is not the best action movie, nor the best dedication to the efforts of Hollywood stunt performers, but walking away, I cannot help but think it’s perhaps the most summer blockbuster-y movie I’ve ever seen, a celebration of the magic of movies, the escapism of blockbusters, and the unsung heroes of the stunt community that deserve recognition and maybe even their own Oscar category. This is the kind of movie that reawakens feelings of cinematic elation, of what blockbuster cinema can accomplish with the right creatives in alignment, leaving a smile plastered across your face and a spring in your step leaving the theater. The Fall Guy is about our love of big stars, big explosions, big feelings, and the people responsible for making those big dreams a reality.

The Fall Guy, loosely based upon the 1980s TV series starring Lee Majors, is not the best action movie, nor the best dedication to the efforts of Hollywood stunt performers, but walking away, I cannot help but think it’s perhaps the most summer blockbuster-y movie I’ve ever seen, a celebration of the magic of movies, the escapism of blockbusters, and the unsung heroes of the stunt community that deserve recognition and maybe even their own Oscar category. This is the kind of movie that reawakens feelings of cinematic elation, of what blockbuster cinema can accomplish with the right creatives in alignment, leaving a smile plastered across your face and a spring in your step leaving the theater. The Fall Guy is about our love of big stars, big explosions, big feelings, and the people responsible for making those big dreams a reality.

Colt Seavers (Ryan Gosling) is a professional movie stuntman who feels invincible until one stunt goes wrong, causing him to break his back. After a year of recovery, he’s parking cars when he gets a call that his ex-girlfriend Jody (Emily Blunt) is directing her first movie, a major sci-fi blockbuster called Metalstorm (which actually exists, it’s a 1983 movie directed by Charles Band and was the shares the same bombastic tagline: “It’s High Noon at the end of the universe”). They need a replacement stuntman and perhaps he can reconnect with her and start over. Also, Colt becomes entangled in searching for the missing star of the movie, Tom Ryder (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), a famous action star that Colt worked closely with, performing his stunts. Colt has to try and find this missing moron while keeping to the movie schedule, all the while hoping to win back Jody and make sure her movie finishes its costly production with its leading man.

First of all, this is the Ryan Gosling show. If you’re a fan of the actor, especially his cavalier charisma that almost comes across as so cocksure to be enviably casual, then The Fall Guy is going to be a dream come true. It takes the Gosling of such comically committed, goofy, un-self-conscious performances from Barbie to The Nice Guys, and it builds a big Hollywood action movie around that persona, vaulting Gosling into his Big Movie Star phase with aplomb. He’s so effortlessly engaging as our hero, even when he’s being battered and bruised and exploded all over the screen. Colt is also immediately appealing as a capable man beset by challenges rediscovering his mojo. He’s been humbled by life and fights for his dignity while at the same time fighting to win back his girl, and it all plays on a breezy, light-hearted comedy wavelength that accepts the inherent and lasting appeal of movie stars being allowed to be movie stars. There might not be much to the characters of Colt and in particular Jody, but the movie just shimmers on their winning chemistry. You’ll yearn for them to be together again with quite little prompting. It’s a movie whose romantic force is front and center. It’s so unabashedly sincere too. When Colt is jamming to Taylor Swift’s “All Too Well,” it’s not an easy point of mockery, though some may take it as such seeing our strong hero in his feelings, but a point of reliability. It’s a movie unafraid of romance, of wearing its heart on its sleeve, and being a little square.

First of all, this is the Ryan Gosling show. If you’re a fan of the actor, especially his cavalier charisma that almost comes across as so cocksure to be enviably casual, then The Fall Guy is going to be a dream come true. It takes the Gosling of such comically committed, goofy, un-self-conscious performances from Barbie to The Nice Guys, and it builds a big Hollywood action movie around that persona, vaulting Gosling into his Big Movie Star phase with aplomb. He’s so effortlessly engaging as our hero, even when he’s being battered and bruised and exploded all over the screen. Colt is also immediately appealing as a capable man beset by challenges rediscovering his mojo. He’s been humbled by life and fights for his dignity while at the same time fighting to win back his girl, and it all plays on a breezy, light-hearted comedy wavelength that accepts the inherent and lasting appeal of movie stars being allowed to be movie stars. There might not be much to the characters of Colt and in particular Jody, but the movie just shimmers on their winning chemistry. You’ll yearn for them to be together again with quite little prompting. It’s a movie whose romantic force is front and center. It’s so unabashedly sincere too. When Colt is jamming to Taylor Swift’s “All Too Well,” it’s not an easy point of mockery, though some may take it as such seeing our strong hero in his feelings, but a point of reliability. It’s a movie unafraid of romance, of wearing its heart on its sleeve, and being a little square.

It’s also clearly a celebration of the unheralded stunt performers of Hollywood history filling in for the more dangerous derring-do of our big screen heroes and villains. Director David Leitch (Atomic Blonde, Bullet Train) came from the stunt world and stages his action set pieces to rely heavily upon real physical stunt work, practical effects, and giving extra time for the audience to understand various dangers and know-how, to learn about this often overlooked industry of professionals risking life and limb, and sometimes giving their own, to create the illusions. The action is varied and filmed in pleasing compositions to highlight the readability of the action. It’s big and propulsive and fun. That’s the key to all of Leitch’s moves here, making the fun infectious, extending the action into unexpected yet delightful directions for more payoffs. The climax involves branching out to an armada of movie stunt performers and technicians, and it feels like a communal effort to win the day, making the ending feel celebratory and satisfying.

This goes along with the behind-the-scenes camaraderie of the found families of filmmaking, celebrating all the many collaborators that go into building these large-scale entertainment ventures. When they’re going through the steps of how to capture a big explosion or stunt, it’s educating the audience along to better anticipate and appreciate. The Fall Guy is clear about its sincere homages, recreating moods and style from action veterans like Michael Mann, James Cameron, and Michael Bay. It’s a movie celebrating movies, and if you’re a fan of the process like me, then you’ll easily join in on the revelry. I’m sure there are famous stunt performers littered throughout, getting Leitch’s favorite colleagues the platform they deserve. The movie’s insider satire is pretty glancing, without anything too vicious or specific about Hollywood stars, especially epitomized by Taylor-Johnson’s send-up of self-absorbed actors. The concept of Metalstorm, a sci-fi Western with elements of Dune and Mad Max, is a project where the silly mash-up of “cool” elements is the unspoken punchline, the sheer stupidity of this concept, magnified by Tom Ryder channeling his most laconic Matthew McConaughey impression.

This goes along with the behind-the-scenes camaraderie of the found families of filmmaking, celebrating all the many collaborators that go into building these large-scale entertainment ventures. When they’re going through the steps of how to capture a big explosion or stunt, it’s educating the audience along to better anticipate and appreciate. The Fall Guy is clear about its sincere homages, recreating moods and style from action veterans like Michael Mann, James Cameron, and Michael Bay. It’s a movie celebrating movies, and if you’re a fan of the process like me, then you’ll easily join in on the revelry. I’m sure there are famous stunt performers littered throughout, getting Leitch’s favorite colleagues the platform they deserve. The movie’s insider satire is pretty glancing, without anything too vicious or specific about Hollywood stars, especially epitomized by Taylor-Johnson’s send-up of self-absorbed actors. The concept of Metalstorm, a sci-fi Western with elements of Dune and Mad Max, is a project where the silly mash-up of “cool” elements is the unspoken punchline, the sheer stupidity of this concept, magnified by Tom Ryder channeling his most laconic Matthew McConaughey impression.

There’s a special appeal about summer blockbuster movies and The Fall Guy understands that lasting appeal. It delivers a movie whose mission is to remind us why we love these kinds of movies, big and stylish and thrilling and romantic and enchantingly entertaining. It’s a movie that’s only interested in being two hours of excellent escapism, not setting up a cinematic universe or the next sequel leading to the next sequel and spin-off. It’s only concerned with telling its lone story, which is booed by the magnetic power of its leads and their buzzy chemistry together. Gosling is chiefly in the zone and supremely charming and funny. The Fall Guy is a treat for fans of action and the professionals that make all the action so incredible.

As a personal side note, my lovely wife is almost five months pregnant and we were informed that our little baby boy would develop his sense of hearing around this time, and during the many action scenes roaring in the surround sound theater, the kiddo was moving around in utero. Either this kid was worried about the sudden shifts in volume and noise, or he was enjoying the experience and swimming along. Either way, I’ll consider this baby’s first movie, so thank you The Fall Guy for making this a personal landmark for me and my growing family.

As a personal side note, my lovely wife is almost five months pregnant and we were informed that our little baby boy would develop his sense of hearing around this time, and during the many action scenes roaring in the surround sound theater, the kiddo was moving around in utero. Either this kid was worried about the sudden shifts in volume and noise, or he was enjoying the experience and swimming along. Either way, I’ll consider this baby’s first movie, so thank you The Fall Guy for making this a personal landmark for me and my growing family.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Jersey Girl (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released March 25, 2004:

Writer/director Kevin Smith (Dogma) takes a stab at family friendly territory with the story of Ollie Trinke (Ben Affleck), a music publicist who must give up the glamour of the big city to realize the realities of single fatherhood. Despite brief J. Lo involvement, Jersey Girl is by no means Gigli 2: Electric Boogaloo. Alternating between edgy humor and sweet family melodrama, Smith shows a growing sense of maturity. Liv Tyler stars as Maya, a liberated video store clerk and Ollie’’s real love interest. Tyler and Affleck have terrific chemistry and their scenes together are a playful highlight. The real star of Jersey Girl is nine-year-old Raquel Castro, who plays Ollie’’s daughter. Castro is delightful and her cherubic smile can light up the screen. Smith deals heavily with familiar clichés (how many films recently end with some parent rushing to their child’’s theatrical production?), but at least they seem to be clichés and elements that Smith feels are worth something. Much cute kiddie stuff can be expected, but the strength of Jersey Girl is the earnest appeal of the characters. Some sequences are laugh-out-loud funny (like Affleck discovering his daughter and a neighbor boy engaging in “the time-honored game of “doctor””), but there are just as many small character beats that could have you feeling some emotion. A late exchange between Ollie and his father (George Carlin) is heartwarming, as is the final image of the movie, a father and daughter embracing and swaying to music. Jersey Girl proves to be a sweetly enjoyable date movie from one of the most unlikely sources.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

When I started putting together my list of 2004 movies to re-watch for this year’s slate, my wife was not pregnant. We had been trying for a year and experienced some heartbreaking setbacks, but now, as I write my review of Jersey Girl, my reality is that my wife is indeed pregnant, and we’re expecting a baby this October and very excited. As you can expect, I’m also nervous. Now this movie about the changes of fatherhood has significantly more meaning for me personally.

In 2004, I was but a 22-year-old soon-to-be college graduate but also a devotee of writer/director Kevin Smith since my teenage years of discovering movies in the oh-so-exciting go-go decade of 1990s independent film. This was supposed to be Smith’s career pivot, as he’d reportedly closed the book on his View Askew universe of crude comedies and stoner hi-jinks with 2001’s Jay and Silent Bob Strikes Back. Smith had become a parent in 1999 and, naturally, this altered the kinds of stories he wanted to tell. Although this didn’t last too long. In 2004, America was sick of Bennifer 1.0 and Jersey Girl was the second movie in less than a year pairing real-life couple Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez. The stink from 2003’s Gigli, and the tabloid overexposure, had tamped down the country’s demand for more Bennifer, so Miramax removed all publicity of Lopez from the movie, pushed the release date back half a year, and even publicly revealed that Lopez’s character dies in childbirth in the first ten minutes. Even with its relatively modest budget for a studio film, Jersey Girl under-performed, critics lambasted it, and Smith returned to his vulgar adult comedy playground with 2006’s Clerks II, the sequel to where it all began. With the occasional stop into horror, Smith has stayed in his own insular world and only gotten more insular with sequels to his early comedies for his ever-shrinking fandom.

More so than any other movie, Jersey Girl is the outlier, the oddity, the path not taken. Watching it again in 2024, I’m more forgiving of this outlier even if it proves harder to love. Much of this is likely my own relatability with the main character’s plight, a New York City workaholic publicist Ollie Trinkie (Affleck) who loses everything in a short window of time, namely his high-profile city job and his wife Gertrude (Lopez). Now he’s back living with his father Bart (George Carlin) in New Jersey and raising a little girl Gertie (Raquel Castro) on his own. It’s not a revolutionary film concept, a selfish adult takes on the responsibility of another and changes their perception of themself and the world. In a way, it likely happens to every new parent, or I would hope, a paradigm shift of perspective. The insights that Jersey Girl offers about parenthood and priorities are nothing new but that doesn’t mean they are bad or not worthwhile. Without the context of Smith’s tonal pivot, Jersey Girl would likely be forgotten, more than it already has been to history. It’s Smith’s spin on the family movie cliches we’ve seen before, and that means there’s a limit to how much further he can take the overly familiar.

More so than any other movie, Jersey Girl is the outlier, the oddity, the path not taken. Watching it again in 2024, I’m more forgiving of this outlier even if it proves harder to love. Much of this is likely my own relatability with the main character’s plight, a New York City workaholic publicist Ollie Trinkie (Affleck) who loses everything in a short window of time, namely his high-profile city job and his wife Gertrude (Lopez). Now he’s back living with his father Bart (George Carlin) in New Jersey and raising a little girl Gertie (Raquel Castro) on his own. It’s not a revolutionary film concept, a selfish adult takes on the responsibility of another and changes their perception of themself and the world. In a way, it likely happens to every new parent, or I would hope, a paradigm shift of perspective. The insights that Jersey Girl offers about parenthood and priorities are nothing new but that doesn’t mean they are bad or not worthwhile. Without the context of Smith’s tonal pivot, Jersey Girl would likely be forgotten, more than it already has been to history. It’s Smith’s spin on the family movie cliches we’ve seen before, and that means there’s a limit to how much further he can take the overly familiar.

It’s a little deflating to watch an artist known for his imagination and vocabulary utilizing the building blocks of maudlin family movies for his new story. Even with a different storyteller, they are still the same recognizable pieces seen before in hundreds of other feel-good movies about parents learning that children are more important than that big meeting or promotion. Of course reducing everything down in life is reductive, and maybe that big meeting could allow the parent to be more present for their kid, provide a better life being neglected, but whenever you set up the climactic choice between family and career, family always wins. Maybe David Wain (They Came Together) is the kind of subversive genre artist who could send up these age-old cliches and end with the workaholic parent choosing their selfish career. Regardless, the movie’s strengths are its sincerity rather than ironic detachment. It would be hard to make this kind of movie from a cynical smart-alecky approach, and Jersey Girl reveals what any View Askew fan has long known, that deep down at heart Smith is a big softie. It’s more apparent nowadays with Smith’s recent output of increasingly sentimental movies about relationships, as well as Smith’s copious social media posts showcasing his torrent of tears in response to a movie or TV show (as a man who frequently cries from movies and TV, this is no affront to me). Smith wanted to tell a personal story of his own life changes through the familiar family movie vehicle, and while it doesn’t entirely stretch beyond its copious influences, it’s still singing true to Smith’s sincerity.