Blog Archives

Bugonia (2025)

A remake of a 2003 South Korean movie, Bugonia is an engaging conflict that needed further restructuring and smoothing out to maximize its entertainment potential. Jessie Plemons stars as a disturbed man beholden to conspiracy theories, namely that the Earth is populated with aliens among us that are plotting humanity’s doom. He kidnaps his corporate boss, a cold and cutthroat CEO (Emma Stone), who he is convinced is really an Andromedan and can connect him with the other aliens. The problem here is that the story can only go two routes. Either Plemons’ character is just a dangerous nutball and has convinced himself of his speculation and this will lead to tragic results, or his character will secretly be right despite the outlandish nature and specificity of his conspiracy claims. Once you accept that, it should become more clear which path offers a more memorable and interesting story. The appeal of this movie is the tense hostage negotiation where this woman has to wonder how to play different angles to seek her freedom from a deranged kidnapper. Both actors are at their best when they’re sparring with one another, but I think it was a mistake to establish so much of Plemons and his life before and during the kidnapping. I think the perspective would have been improved following Stone from the beginning and learning as she does, rather than balancing the two sides in preparation. The bleak tone is par for a Yorgos Lanthimos (Poor Things) movie but the attempts at humor, including some over-the-top gore as slapstick, feel more forced and teetering. I never found myself guffawing at any of the absurdity because it’s played more for menace. The offbeat reality that populates a Lanthimos universe is too constrained to the central characters, making the world feel less heightened and weird and therefore the characters are the outliers. I enjoyed portions of this movie, and Stone’s performance has so many layers in every scene, but Bugonia feels like an engaging premise that needed more development and focus to really get buggy.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Highest 2 Lowest (2025)

Spike Lee’s remake of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, both of them based upon the novel King’s Ransom, is a movie in desperate need of a stronger identity. Every “Spike Lee joint” is definitely an experience that few can imitate, and his personal predilections and stylish direction often elevates the movie into something more engaging and intriguing. We follow Denzel Washington as David King, or “King David,” a middle-aged record company president who is at a career and personal crossroads. He’s trying to negotiate back enough capital to buy back controlling interest in his company, to ward off being bought by a soulless conglomerate that has no interest in protecting the decades of Black musicians given platforms. His teenage son is also kidnapped, except it’s revealed that the kidnappers nabbed the wrong kid; they grabbed the son of his chauffeur (Jeffrey Wright) instead. The movie is at its most entertaining when it dwells in this moral quandary of whether David feels as compelled to pay the ransom when it’s someone else’s child, especially when he needs that money to regain his company. I wish the entire movie had been spent over this agonizing personal guilt crucible. This is the hook of the movie. I found it hard to care once the money went out. But then David agrees to meet the ransom, deliver it personally, and it becomes a generic police thriller from there, including an Act Three where David tracks down the culprit. It’s just far less interesting than the personal stakes of what occurred earlier. There’s also an ongoing digression of analyzing what it means to be a successful Black musician, enough so that the movie literally ends on an uninterrupted musical audition meant to symbolize David feeling like the music matters to him again after so long, that this ordeal has refocused his attention to What Actually Matters. It just doesn’t feel like it meshes with the trail of conscience nor the police thriller. Highest 2 Lowest ends up being stretched into too many directions, chasing after a relevancy that seems just outside its grasp. Lee and Washington have certainly done better together.

Spike Lee’s remake of Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, both of them based upon the novel King’s Ransom, is a movie in desperate need of a stronger identity. Every “Spike Lee joint” is definitely an experience that few can imitate, and his personal predilections and stylish direction often elevates the movie into something more engaging and intriguing. We follow Denzel Washington as David King, or “King David,” a middle-aged record company president who is at a career and personal crossroads. He’s trying to negotiate back enough capital to buy back controlling interest in his company, to ward off being bought by a soulless conglomerate that has no interest in protecting the decades of Black musicians given platforms. His teenage son is also kidnapped, except it’s revealed that the kidnappers nabbed the wrong kid; they grabbed the son of his chauffeur (Jeffrey Wright) instead. The movie is at its most entertaining when it dwells in this moral quandary of whether David feels as compelled to pay the ransom when it’s someone else’s child, especially when he needs that money to regain his company. I wish the entire movie had been spent over this agonizing personal guilt crucible. This is the hook of the movie. I found it hard to care once the money went out. But then David agrees to meet the ransom, deliver it personally, and it becomes a generic police thriller from there, including an Act Three where David tracks down the culprit. It’s just far less interesting than the personal stakes of what occurred earlier. There’s also an ongoing digression of analyzing what it means to be a successful Black musician, enough so that the movie literally ends on an uninterrupted musical audition meant to symbolize David feeling like the music matters to him again after so long, that this ordeal has refocused his attention to What Actually Matters. It just doesn’t feel like it meshes with the trail of conscience nor the police thriller. Highest 2 Lowest ends up being stretched into too many directions, chasing after a relevancy that seems just outside its grasp. Lee and Washington have certainly done better together.

Nate’s Grade: C+

The Crow (2024)

It’s been over twenty years since there’s been a movie based upon James O’Barr’s iconic graphic novel The Crow, and it’s been almost thirty years since there was a theatrically released movie. It’s a franchise that seems easy enough to make into a movie: a victim of violence comes back from the dead with some supernatural guidance to seek vengeance on those who killed them. Slather it in a moody atmosphere and some nice character beats, and you have yourself a born winner, like the 1994 movie that became a staple for a generation of disaffected teenagers. So why has it been so hard to bring this franchise back to life? There have been many starts and stops, with different directors and actors becoming attached and leaving over time, including Bradley Cooper, Luke Evans, Jason Momoah, and Alexander Skarsgard. Apparently, the producers finally found a story they felt could support a Crow reboot, or so they hoped. It crashed pretty hard at the box-office upon release. Despite its omnipresent placement on many worst of 2024 lists, I didn’t hate The Crow 2024. It has some serious problems but it also has some intriguing ideas that could have worked in a better version. It’s far less egregious than the 2005 Wicked Prayer where a literal plot point is stopping a climactic consummation between a villainous Tara Reid and David Boreanaz. It couldn’t be that bad, could it? It’s not, but it needed a lot of work.

It’s been over twenty years since there’s been a movie based upon James O’Barr’s iconic graphic novel The Crow, and it’s been almost thirty years since there was a theatrically released movie. It’s a franchise that seems easy enough to make into a movie: a victim of violence comes back from the dead with some supernatural guidance to seek vengeance on those who killed them. Slather it in a moody atmosphere and some nice character beats, and you have yourself a born winner, like the 1994 movie that became a staple for a generation of disaffected teenagers. So why has it been so hard to bring this franchise back to life? There have been many starts and stops, with different directors and actors becoming attached and leaving over time, including Bradley Cooper, Luke Evans, Jason Momoah, and Alexander Skarsgard. Apparently, the producers finally found a story they felt could support a Crow reboot, or so they hoped. It crashed pretty hard at the box-office upon release. Despite its omnipresent placement on many worst of 2024 lists, I didn’t hate The Crow 2024. It has some serious problems but it also has some intriguing ideas that could have worked in a better version. It’s far less egregious than the 2005 Wicked Prayer where a literal plot point is stopping a climactic consummation between a villainous Tara Reid and David Boreanaz. It couldn’t be that bad, could it? It’s not, but it needed a lot of work.

Eric Draven (Bill Skarsgard) meets the love of his life, Shelly (FKA Twigs), where one meets all the hot and available singles these days – in drug rehab. She’s on the run from a criminal enterprise after she kept an incriminating video, so once she and Eric escape from their rehab center and try and make a go at a new life on the outside, the goons find them and kill them both. Except Eric’s spirit is sent to a purgatory netherworld and tge mysterious man Kronos offers to send him back to get vengeance. It seems this crime syndicate is led by Vincent Roeng (Danny Huston), who happens to be perpetuating his lifespan by offering fresh innocent souls to Hell. With the supernatural power of a guardian crow providing him invulnerability, Eric seeks to stop these bad people from dooming any other souls and maybe he can save Shelly’s soul in the process.

Let’s tackle some of the more noteworthy mistakes of the reboot before I begin providing the compliments and where I think the movie actually has some worthy ideas. The biggest creative mistake is delaying the tragically fateful murder that spurs the entire movie until 45 minutes in. For contrast, the original movie has its Eric and Shelly getting killed through an opening montage. It doesn’t waste any time getting to the real premise of the material, the supernatural revenge tale. If you’re going to delay that key turn by so long, then that relationship better pop off the screen, or the chemistry has to be amazing, or the characters are so in depth and charming that with the considerably increased time we will feel a deep pain at the loss. If you’re putting more weight on the love story and their connection then you have to back it up, and this movie cannot. Therefore, it’s drawing out its necessary supernatural transformation to a point that there is only a measly hour left for all that superhuman stalking and avenging.

Let’s tackle some of the more noteworthy mistakes of the reboot before I begin providing the compliments and where I think the movie actually has some worthy ideas. The biggest creative mistake is delaying the tragically fateful murder that spurs the entire movie until 45 minutes in. For contrast, the original movie has its Eric and Shelly getting killed through an opening montage. It doesn’t waste any time getting to the real premise of the material, the supernatural revenge tale. If you’re going to delay that key turn by so long, then that relationship better pop off the screen, or the chemistry has to be amazing, or the characters are so in depth and charming that with the considerably increased time we will feel a deep pain at the loss. If you’re putting more weight on the love story and their connection then you have to back it up, and this movie cannot. Therefore, it’s drawing out its necessary supernatural transformation to a point that there is only a measly hour left for all that superhuman stalking and avenging.

In the original, Eric (Brandon Lee) tracked down the gang responsible for his and his wife’s murder and each member got their own section where they established their character. Each section allowed us to learn more about the powers Eric now had at his disposal as well as how they might change him. The structure allows the bad guys to learn about their predicament and plan a defense. It allows the exciting elements from the premise to develop and adapt. With The Crow 2024, there’s one initial attack where Eric discovers he can bounce back from bullets, then there’s one ambush on a car carrying our bad guys, and finally there’s an extended assault at an opera that gruesomely kills every disposable henchman money can buy. That’s it. Eric isn’t picking them off one-by-one or even working up the food chain to the really bad guys. The bad guys don’t even seem that threatened, as Vincent is still going about his routines, albeit with more armored guards. It makes the whole Crow parts of The Crow feel small and underdeveloped. This is the first Crow movie where the titular bird, the symbolic partner from the underworld, doesn’t even connect in any meaningful way. It’s just a background “caw.”

The entire inclusion of a villain who traffics innocent souls begs for further examination and probably a more formidable opponent. Vincent confesses he’s hundreds of years old and his agreement is with the Devil himself, so you would think this man would have learned some tricks in the ensuing hundreds of years. He has some vague super power where he can whisper suggestions into the ears of his victims and they’ll do what he commands, but does he use this power when he’s battling Eric or trying to flee from Eric? No. The demonstration of this super power basically resorts to being a more personal form of torture. Vincent doesn’t even seem worried about an undead warrior coming for him. Maybe that’s centuries of accrued over confidence, but if that’s the case, then make us love to hate this arrogant bastard. Also, if he’s had a successful transactional arrangement with the Devil for literal centuries, shouldn’t Ole Scratch have a thing or two to say about his soul supplier being brought to cosmic justice? If innocent souls are so much more delicious to the Prince of Darkness, there’s more to lose, and maybe that even brings the horned one into the fray, or he designates a promising underling or nepo baby demon, and then Eric has to fight the literal powers of Hell as well protecting his target, which raises the question how far is he willing to go to seek the vengeance that he craves.

The entire inclusion of a villain who traffics innocent souls begs for further examination and probably a more formidable opponent. Vincent confesses he’s hundreds of years old and his agreement is with the Devil himself, so you would think this man would have learned some tricks in the ensuing hundreds of years. He has some vague super power where he can whisper suggestions into the ears of his victims and they’ll do what he commands, but does he use this power when he’s battling Eric or trying to flee from Eric? No. The demonstration of this super power basically resorts to being a more personal form of torture. Vincent doesn’t even seem worried about an undead warrior coming for him. Maybe that’s centuries of accrued over confidence, but if that’s the case, then make us love to hate this arrogant bastard. Also, if he’s had a successful transactional arrangement with the Devil for literal centuries, shouldn’t Ole Scratch have a thing or two to say about his soul supplier being brought to cosmic justice? If innocent souls are so much more delicious to the Prince of Darkness, there’s more to lose, and maybe that even brings the horned one into the fray, or he designates a promising underling or nepo baby demon, and then Eric has to fight the literal powers of Hell as well protecting his target, which raises the question how far is he willing to go to seek the vengeance that he craves.

That question is actually one of the more interesting points because this version of The Crow directly connects the hero’s strength to the power of love. This is where putting more emphasis and time with the love story could have worked… had the love story been compelling. I like that it’s not his hatred that gives him his powers but his love for Shelly. The movie also provides a more urgent reason for Eric to make these bad men feel his crow-y wrath: he can retrieve her from Hell if he thwarts Vincent and his soul-trafficking gang. Even though she’s dead, he can still save her, and that is meaningful and provides a better motivation for our protagonist. I don’t know why, and it seems like this Kronos guy could be far more active and helpful as an otherworldly guide, but it’s an effective goal to drive our hero to slay his targets. I liked that late in the movie, after he receives some upsetting news about Shelly, his conflicted feelings are detracting from his super powers. There’s a direct and personal sense of causality. His doubts in whether he loved Shelly are manifesting as physical vulnerability. This approach could have worked had the filmmakers given the audience an engaging love story. The movie also feels built around hiding the acting limitations of Twigs (Honeyboy). She tries but this performance feels so listless and lacking a spark or charisma that could convince why Eric would risk it all for her.

There’s one notable action sequence and it deserves some kudos for its morbid invention. When you have a hero that can take all the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, it can lessen the stakes when it seems like they lack a credible weakness (call it the “Superman problem”). However, what I liked about the 2024 Crow is that even though he’s an undead warrior, that doesn’t mean Eric is somehow superior at fighting. He can take more punishment but that doesn’t mean he’s become an exemplary martial arts fighter, agile gymnast, or trained marksman. He’s still just a lanky guy, albeit one with washboard abs, the sculpted physique one naturally develops while recovering from substance abuse, of course. I enjoyed that this version of Eric was still struggling in his fights and could fall down and be bested. For his big assault scene at the opera house, he prioritizes a sword as his weapon of choice. At least that necessitates proximity to take out his opponents. The extended and very bloody fight scene is inventively gruesome; at one point, Eric uses the sword sticking out of his chest to lean forward and impale a henchman pinned on the floor. He even shoots through holes in his body to take out henchmen grappling him from behind. It’s the most thought put into utilizing the possibility of its premise. I don’t know why the rest of the movie couldn’t exhibit that same level of thought and creativity.

There’s one notable action sequence and it deserves some kudos for its morbid invention. When you have a hero that can take all the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, it can lessen the stakes when it seems like they lack a credible weakness (call it the “Superman problem”). However, what I liked about the 2024 Crow is that even though he’s an undead warrior, that doesn’t mean Eric is somehow superior at fighting. He can take more punishment but that doesn’t mean he’s become an exemplary martial arts fighter, agile gymnast, or trained marksman. He’s still just a lanky guy, albeit one with washboard abs, the sculpted physique one naturally develops while recovering from substance abuse, of course. I enjoyed that this version of Eric was still struggling in his fights and could fall down and be bested. For his big assault scene at the opera house, he prioritizes a sword as his weapon of choice. At least that necessitates proximity to take out his opponents. The extended and very bloody fight scene is inventively gruesome; at one point, Eric uses the sword sticking out of his chest to lean forward and impale a henchman pinned on the floor. He even shoots through holes in his body to take out henchmen grappling him from behind. It’s the most thought put into utilizing the possibility of its premise. I don’t know why the rest of the movie couldn’t exhibit that same level of thought and creativity.

If you’re a fan of the comic or the 1994 movie, you’ll more than likely walk away from this newest Crow with some degree of disappointment. It wasn’t worthy of a placement on my own worst of the year list. Rather, it appears as a middling dark thriller that has some interesting creative choices that fail to pan out because the follow-through wasn’t as good as the idea. With a few more revisions, I think this basic approach could work, emphasizing the love story and devoting precious time to make it more impactful than just an innocent woman being avenged. However, by not fulfilling the possibility of these choices, instead we’re stuck with a lackluster romance eating up 45 minutes of screen time that could have been used for more satisfying supernatural action. By its sloppy end, I was just left shrugging. If this is what twenty-plus years of development wrought, maybe we needed a little longer for better results.

Nate’s Grade: C

Nosferatu (2024)

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Director Robert Eggers’ remake of a famous rip-off of the most famous blood-sucker in literature is a finely crafted and highly atmospheric drop into the past, as should be expected from Eggers (The Witch, The Northman). It doesn’t redefine cinematic vampires but rather puts the story through the contemporary lens of a toxic ex-boyfriend who refuses to relinquish what he feels belongs to him. The story should be familiar to most, even if they never watched the original 1922 silent film, nor its 1970s remake by Werner Herzog. Bill Skarsgaard plays the mysterious and threatening Count Orlock, a wealthy Transylvanian outsider looking to relocate to the big city in Germany, primarily to prey upon poor Ellen Hunter (Lily-Rose Depp), the “one who got away,” so to speak. He haunts her dreams and drives her mad, with Depp mesmerized and convulsing most convincingly. From there it’s a battle between Ellen’s husband (Nicholas Hoult) and an expert in the occult (Willem Defoe) over whose will will win out. Skarsgaard is fascinating and chilling and you too may want to imitate the thick-as-stew Count Orlock accent afterwards. The technical elements of this movie are masterful, from production design, to costuming, to the gas-lit and moody photography. Eggers is a deeply sincere filmmaker who translates his passions and madness onto the big screen with loving care. Nosferatu is gorgeous and unnerving, though I’m hesitant to say it rivals Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula movie for modern vampire artistic triumph and pure horniness. It’s a gussied-up B-movie with a deeply committed filmmaker to deeply realized genre filmmaking, and so Nosferatu is an entertaining remake that most vampire fans will be happy to sink their teeth into this holiday season.

Nate’s Grade: B

Mean Girls (2024)

Child: “I want Mean Girls [2024], mom.”

Child: “I want Mean Girls [2024], mom.”

Parent: “We have Mean Girls [2004] at home.”

Consider this bouncy 2024 remake Mean Girls Plus, as the only additions from the popular high school comedy are the adaptations made to retrofit Tina Fey’s comedy for the Broadway stage. Twenty years later, the cast is more diverse, some of the jokes that have aged the worst have been removed (fewer fat jokes and no more teachers sleeping with underage Asian students), and the 97-minute original now becomes a 112-minute musical. The cast is winsome and charming but fail to disperse your memories of the original cast that featured future Oscar nominees Rachel McAdams and Amanda Seyfried or even Lindsay Lohan during the height of her career (Lohan cameos as the mathlete judge). Renee Rapp (The Sex Lives of College Girls) has got the most command as this next generation’s Regina George, a role she played during the Broadway run. Your overall impression is going to hinge entirely upon your evaluation of the pop-heavy songs, which to my ears were pleasant but unmemorable melodic pap. There is the occasional snarky line (“This is modern feminism talking/ Watch me as I run the world in shoes I cannot walk in”) but most of the lyrics and jokes are mild additions from what Fey’s movie already established. The standout musical moment might be a goofy throwaway number about all the different sexy Halloween costumes a woman should be able to dress in (“If you don’t dress slutty, that is slut shaming us”). The staging features lots of long takes and tracking shots to better appreciate the nimble dance choreography with the occasional visual addition (phone screen inserts make for modern backup singers). The memorable 2004 lines that have stuck as Millennial memes are included but treated like returning victors, but when elevated and given space for applause, it feels so strange and artificial. The 2004 movie didn’t do this. Regardless, you can do worse than a slightly updated version of Mean Girls with all-right songs, though you could also simply re-watch the original.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Love Again (2023)/ Rye Lane (2023)

Romantic comedies used to be a powerhouse of Hollywood and now it feels like they’ve all disappeared from your local multiplex. Rom-coms gave us industry stars, careers, and household names, the likes of modern rom-com royalty including Nora Ephron, Cameron Crowe, Nancy Myers, and Richard Curtis, and two of which have screenwriting Oscars. It’s a subgenre that is quite often dismissed, usually by condescending men, let’s be honest, as empty-headed maudlin wish-fulfillment. It’s no coincidence that rom-coms are looked at as more of a female-driven genre aimed at a more female-centric audience, so the contemptuous pile-ons from men can often seem like insights into masculine social allowances for empathy. I’ve long been a fan of romantic comedies, even written a few, because they’re just so damn likable. It’s a foundational principle of the genre, to get you to like the characters, their interactions, their courtships. The movie is romancing its audience at the same time the characters are romancing one another, and who doesn’t like to be swooned? Two 2023 rom-coms, Love Again and Rye Lane, showcase directly how appealing and heartwarming and swoon-worthy that excellent rom-coms can prove, and how middling when its genre is taken for granted.

Romantic comedies used to be a powerhouse of Hollywood and now it feels like they’ve all disappeared from your local multiplex. Rom-coms gave us industry stars, careers, and household names, the likes of modern rom-com royalty including Nora Ephron, Cameron Crowe, Nancy Myers, and Richard Curtis, and two of which have screenwriting Oscars. It’s a subgenre that is quite often dismissed, usually by condescending men, let’s be honest, as empty-headed maudlin wish-fulfillment. It’s no coincidence that rom-coms are looked at as more of a female-driven genre aimed at a more female-centric audience, so the contemptuous pile-ons from men can often seem like insights into masculine social allowances for empathy. I’ve long been a fan of romantic comedies, even written a few, because they’re just so damn likable. It’s a foundational principle of the genre, to get you to like the characters, their interactions, their courtships. The movie is romancing its audience at the same time the characters are romancing one another, and who doesn’t like to be swooned? Two 2023 rom-coms, Love Again and Rye Lane, showcase directly how appealing and heartwarming and swoon-worthy that excellent rom-coms can prove, and how middling when its genre is taken for granted.

With Love Again, we follow Mira (Priyanka Chopra Jonas) who is mourning the loss of her deceased boyfriend. She continues to send texts to his old phone number explaining the depth of her grief and confused feelings trying to get her life back on track. It just so happens that her dead boyfriend’s old number has been given to the work phone for Rob (Sam Heughan), a journalist who is getting over his own recent heartbreak. He takes a curiosity to this stranger sending him such heartfelt texts, and after meeting her from afar, decides to try to get to know her better, resulting in the two of them romancing but with the Big Awful Dreadful Secret always waiting to be discovered for the unfortunate Act Two break.

I don’t understand Love Again, like at all. I understand what happened on screen in a literal sense but the reasoning behind it, the storytelling choices, are so bizarre and foreign to me that it feels like a group of aliens who only learned human behavior through the worst direct-to-streaming rom-coms tried their hand at recreating human interactions and falling in love. The very premise seems almost like an afterthought, so why even go through the trouble of this labored conceit? The fact that Rob has been receiving this sad woman’s grief texts could present a real ethical conundrum, beyond the fact that he knows her private thoughts and feelings and he doesn’t even know who she is. The natural angle would be for him to take it upon herself to do small things to make her feel better, maybe from the outside perspective of a secret admirer, a position he never intends to go beyond. The issue becomes when he starts to transition to romance, because now he has a head start that she didn’t even realize was happening. Also, he could make use of the information that she’s been unknowingly feeding him, about favorite foods or interests, to better sweep her off her feet, but that also places us in an ethically dubious scenario of emotional manipulation, akin to what Bill Murray tries to get away with the loops of Groundhog Day. It’s a borderline stalker situation that can easily go too far. The fact that Love Again doesn’t even cover these most obvious plot scenarios makes the entire premise feel perfunctory; it could have been anything that accidentally drew Rob to Mira because it’s so unimaginative and, simply, bad at its own inept storytelling. It’s so baffling and feels like it was made with contempt for its audience, believing that they would accept anything as long as the genre parts were covered, so Love Again’s story is the barest of pained efforts.

I don’t understand Love Again, like at all. I understand what happened on screen in a literal sense but the reasoning behind it, the storytelling choices, are so bizarre and foreign to me that it feels like a group of aliens who only learned human behavior through the worst direct-to-streaming rom-coms tried their hand at recreating human interactions and falling in love. The very premise seems almost like an afterthought, so why even go through the trouble of this labored conceit? The fact that Rob has been receiving this sad woman’s grief texts could present a real ethical conundrum, beyond the fact that he knows her private thoughts and feelings and he doesn’t even know who she is. The natural angle would be for him to take it upon herself to do small things to make her feel better, maybe from the outside perspective of a secret admirer, a position he never intends to go beyond. The issue becomes when he starts to transition to romance, because now he has a head start that she didn’t even realize was happening. Also, he could make use of the information that she’s been unknowingly feeding him, about favorite foods or interests, to better sweep her off her feet, but that also places us in an ethically dubious scenario of emotional manipulation, akin to what Bill Murray tries to get away with the loops of Groundhog Day. It’s a borderline stalker situation that can easily go too far. The fact that Love Again doesn’t even cover these most obvious plot scenarios makes the entire premise feel perfunctory; it could have been anything that accidentally drew Rob to Mira because it’s so unimaginative and, simply, bad at its own inept storytelling. It’s so baffling and feels like it was made with contempt for its audience, believing that they would accept anything as long as the genre parts were covered, so Love Again’s story is the barest of pained efforts.

Love Again is bad in ways that are despairing while also being mind-numbing. You get a sense early on how little feel for the material the filmmakers have, at how poorly the scenes are at disguising their creaky plot mechanics from the viewer. It’s the kind of movie where a kindly bartender introduces himself and seconds later is all, “I sure feel bad about your dead boyfriend.” It’s that kind of movie, the kind with supportive friends and work colleagues who are only there to provide words of encouragement or set the scene in the most transparent and lazy way, “You know you haven’t been the same since…” to better tee up the audience as far as what is important. All movies do this but the exposition needs to be masked with character details or comedic exploits, and the better to visualize a person’s life.

This is also the kind of comedy where the jokes amount to the first idea of every scene, where there is never a subversion or even an escalation or a comedic situation. In this world, Nick Jonas makes a cameo as a bad date who is vainly obsessed with bodybuilding and that is the only joke you’ll get with that appearance to the end. It’s the kind of movie where Mira’s “quirk” is asking dates would you rather scenarios that aren’t even raunchy or extreme or even that telling of her own personality. Her other personality trait is that she likes, get this, putting her French fries on her cheeseburger (what a crazy bohemian!). It’s the kind of movie that has Mira as a children’s book author and doesn’t even bother to provide a scene of her demonstrating her storytelling prowess and insight for creating metaphorical-heavy stories to impart important lessons for children. This technique could have been a greater insight into her emotional state without having to rely upon the character just spouting out her feelings. Even worse, the movie doesn’t use her texts to her beloved as a means of getting to know her better. It’s the very premise of this movie, supposedly. These details meant to give the movie its definition, what separates it from the rom-com pack, but what it produces feels so insufficient and haphazard that you wonder if this was a failed genre MadLibs.

This is also the kind of comedy where the jokes amount to the first idea of every scene, where there is never a subversion or even an escalation or a comedic situation. In this world, Nick Jonas makes a cameo as a bad date who is vainly obsessed with bodybuilding and that is the only joke you’ll get with that appearance to the end. It’s the kind of movie where Mira’s “quirk” is asking dates would you rather scenarios that aren’t even raunchy or extreme or even that telling of her own personality. Her other personality trait is that she likes, get this, putting her French fries on her cheeseburger (what a crazy bohemian!). It’s the kind of movie that has Mira as a children’s book author and doesn’t even bother to provide a scene of her demonstrating her storytelling prowess and insight for creating metaphorical-heavy stories to impart important lessons for children. This technique could have been a greater insight into her emotional state without having to rely upon the character just spouting out her feelings. Even worse, the movie doesn’t use her texts to her beloved as a means of getting to know her better. It’s the very premise of this movie, supposedly. These details meant to give the movie its definition, what separates it from the rom-com pack, but what it produces feels so insufficient and haphazard that you wonder if this was a failed genre MadLibs.

It’s also bad that Chopra Jonas (The Citadel) and Heughan (Outlander) have a remarkable lack of chemistry. They’re both good-looking human beings who have previously shown to be quite capable and appealing actors. I do not blame them for the lack of feeling in this movie. They could only do so much with the poorly written characters and the clunky dialogue. Watching them attempt to flirt with this material is like watching two cats try and recreate the H.M.S. Titanic. It’s just not going to work well.

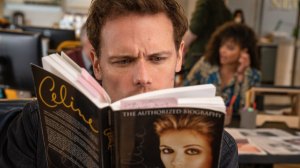

Here’s another example of how poor the filmmakers have developed the elements of their tale. Rob is still mending his broken heart from a fiance that left him a week before their wedding. He is a cynic, although like everything else in this movie, if you push too hard it’s only there as a shallow fixture for story. But if you’re going to make him the cynic, make him believe that love is impossible, it’s a chemical condition of the brain, some delusion, and that this drives his contempt for having to interview Celine Dion, a pop star best known for her soaring ballads about love and sunken ships and hearts going on. He thinks her songs are cheesy and silly, and over the course of the movie, of course he becomes a believer (at least this the movie understands the arc to follow). Again, the most obvious route would be to make him a music critic, someone who decries silly love songs and thinks of them as a destructive drug for the masses. This would make more sense why he’s so irritated at having to cover Dion, and why he would be covering Dion, and it would also make more sense then for his reconsideration. The movie, instead, makes Rob a big fan of… basketball. He loves to watch basketball. Why is this man covering Celine Dion then? If he was going to cover basketball, why not bring his passion for it more into focus, at least as something he can learn from and share with Mira? They share a quick game where she basically says, “I like this game too,” and that’s the rest of this completely underdeveloped characteristic that doesn’t tie back in thematically at all. Again, if you’re going to make this much of Dion’s multiple appearances, including devoting your end credits to having your cast and crew enthusiastically lip sync to her songs, then at least tie her better to your plot.

Here’s another example of how poor the filmmakers have developed the elements of their tale. Rob is still mending his broken heart from a fiance that left him a week before their wedding. He is a cynic, although like everything else in this movie, if you push too hard it’s only there as a shallow fixture for story. But if you’re going to make him the cynic, make him believe that love is impossible, it’s a chemical condition of the brain, some delusion, and that this drives his contempt for having to interview Celine Dion, a pop star best known for her soaring ballads about love and sunken ships and hearts going on. He thinks her songs are cheesy and silly, and over the course of the movie, of course he becomes a believer (at least this the movie understands the arc to follow). Again, the most obvious route would be to make him a music critic, someone who decries silly love songs and thinks of them as a destructive drug for the masses. This would make more sense why he’s so irritated at having to cover Dion, and why he would be covering Dion, and it would also make more sense then for his reconsideration. The movie, instead, makes Rob a big fan of… basketball. He loves to watch basketball. Why is this man covering Celine Dion then? If he was going to cover basketball, why not bring his passion for it more into focus, at least as something he can learn from and share with Mira? They share a quick game where she basically says, “I like this game too,” and that’s the rest of this completely underdeveloped characteristic that doesn’t tie back in thematically at all. Again, if you’re going to make this much of Dion’s multiple appearances, including devoting your end credits to having your cast and crew enthusiastically lip sync to her songs, then at least tie her better to your plot.

Ms. Dion doesn’t need me to defend her. She’s a grown woman and can make her own decisions, and I’m sure she was handsomely paid for her contributions in Love Again whose soundtrack features five new songs and six of her past tunes (why not go the jukebox musical route at that volume?), but I need to further explain the awfulness of Love Again’s choices. Late into the movie, Dion discusses her own personal loss, mourning her husband of twenty-plus years who died in 2016. The fact that this real woman is mining her own real tragedy to provide the emotional boost to our bad protagonist in a bad rom-com just feels morally queasy to me. It just feels wrong, especially in the name of such an undeserving character in an undeserving movie for her to have to rehash her own personal grief.

On the other end of the quality spectrum is Rye Lane, a smaller British indie that follows Dom (David Johnsson) and Yas (Vivian Oparah) through a crazy day and night together across the bounds of South London. She discovers him crying in a toilet stall, a meet-cute so intentionally un-cute. They’re both nursing mixed feelings and unchecked anger over being dumped by their respective exes. Dom discovered his girlfriend cheating on him with his best mate and now he’s scheduled to meet with them both to better clear the air. Yas finally stood up to her neglectful and self-centered sculptor boyfriend but she wants to recollect her favorite record in his flat before she can bid goodbye to him forever. Together, they will help each other through their respective relationship detritus and plot their next steps forward.

On the other end of the quality spectrum is Rye Lane, a smaller British indie that follows Dom (David Johnsson) and Yas (Vivian Oparah) through a crazy day and night together across the bounds of South London. She discovers him crying in a toilet stall, a meet-cute so intentionally un-cute. They’re both nursing mixed feelings and unchecked anger over being dumped by their respective exes. Dom discovered his girlfriend cheating on him with his best mate and now he’s scheduled to meet with them both to better clear the air. Yas finally stood up to her neglectful and self-centered sculptor boyfriend but she wants to recollect her favorite record in his flat before she can bid goodbye to him forever. Together, they will help each other through their respective relationship detritus and plot their next steps forward.

What an immensely charming movie Rye Lane is and it’s one that reminds you about the innate pleasure of the rom-com genre when paired with characters we want to get to know better. Thank goodness the screenwriters keenly understand how to develop our protagonists but also make them imminently winning. By establishing both Dom and Yas as reeling from recent breakups, and from such awful people, it makes us want to root for them to regain their sense of composure, dignity, and personal joy. We want them to show up these people who have made them feel so low, and it just so happens that one another will serve as the ultimate and unexpected wingman. I loved it when Yas buddied up next to Dom and pretended to be his very doting and very sexual new paramour as well as press Dom’s former flame on her own cheating ways, shifting the power dynamic. It supercharges the growing friendship between the two of them as well as reconfirm their need to find a partner who can and will go out of their way for them. Watching each of them encourage and aid the other during a time of need and insecurity serves as a reliable provider of satisfaction and a clear path for us to also fall in love with these unique people.

The writing is so quick-witted and charming that simply listening to these revealing and often hilarious conversations is a pleasure. I’m reminded of Richard Linklater’s famously talkative Before trilogy, another all-in-one-day whirlwind romance of two characters exploring a locale while also exploring one another under a limited period of time. It’s a natural structure because it provides a looming urgency but the drama also unfolds more or less in real time with the characters learning about one another at the same pace that the viewer is, and so our emotions feel better attuned as the characters change their perceptions of one another. This is the joy of rom-coms, finding characters you simply want to spend time with because they’re so charming, interesting, and deserving of finding happiness of their own making. Dom and Yas are wonderful characters separately but the right combination together. He’s more nerdy and awkward and she pushes him to be more assertive and confident. She’s less sure of her worth and sets herself up for sabotage in landing a job she might love, and he refuses to let her let herself down. It’s genuinely amusing and heartwarming to watch these two help one another in their time of need.

The writing is so quick-witted and charming that simply listening to these revealing and often hilarious conversations is a pleasure. I’m reminded of Richard Linklater’s famously talkative Before trilogy, another all-in-one-day whirlwind romance of two characters exploring a locale while also exploring one another under a limited period of time. It’s a natural structure because it provides a looming urgency but the drama also unfolds more or less in real time with the characters learning about one another at the same pace that the viewer is, and so our emotions feel better attuned as the characters change their perceptions of one another. This is the joy of rom-coms, finding characters you simply want to spend time with because they’re so charming, interesting, and deserving of finding happiness of their own making. Dom and Yas are wonderful characters separately but the right combination together. He’s more nerdy and awkward and she pushes him to be more assertive and confident. She’s less sure of her worth and sets herself up for sabotage in landing a job she might love, and he refuses to let her let herself down. It’s genuinely amusing and heartwarming to watch these two help one another in their time of need.

Rye Lane is also peppered with playful and, at times, chaotic visuals to goose up the talky proceedings. Debut director Raine Allen-Miller will often use quick inserts and playful visual framing to add more pizazz to the presentation, like when Yas and Dom present their recollection of events like narrators to a stage play of their own lives. It’s lively and fun but occasionally the visual inserts and sound design, or perhaps the score itself, felt like added distractions to the appealing core elements of the movie. It was the only annoyance I felt in such an otherwise funny and charming movie boasting such winning performances. It felt a little unnecessary at times and seemed like the filmmakers had doubts that the material and the performances themselves were enough to sell the entertainment of the movie.

Romantic comedies remind me of the old saying, “it’s not the singer, it’s the song.” They’re like many other sub-genres of movies and storytelling itself, complete with expectations and formulas and rules and recognizable parts and pieces that add up to, hopefully, entertainment. In this regard, movies are like a meal, and two people can follow the same recipe with the same ingredients and concoct two totally different final creations. Fans of rom-coms are like fans of any other genre, looking for good storytellers to value their time and give them an escape. It’s not just that the familiar elements are included, it’s what is done with them, the care and affection from the storytellers, chiefly creating characters that you can fall in love with and root for their own happiness and fortuitous fortunes.

Romantic comedies remind me of the old saying, “it’s not the singer, it’s the song.” They’re like many other sub-genres of movies and storytelling itself, complete with expectations and formulas and rules and recognizable parts and pieces that add up to, hopefully, entertainment. In this regard, movies are like a meal, and two people can follow the same recipe with the same ingredients and concoct two totally different final creations. Fans of rom-coms are like fans of any other genre, looking for good storytellers to value their time and give them an escape. It’s not just that the familiar elements are included, it’s what is done with them, the care and affection from the storytellers, chiefly creating characters that you can fall in love with and root for their own happiness and fortuitous fortunes.

Love Again is based on the 2016 German film Text For You, itself based on a 2009 German novel (I watched the trailer on YouTube, and it’s weird having actors refer to text messages as “SMS-es”). It’s a reminder of how soulless the worst of these lazy rom-coms can feel when producers look to check boxes to fulfill some list of genre requirements that they think will satisfy the lowest expectations of a gullible fan base they can exploit. Rye Lane is the latest example of the real pleasures of a finely developed rom-com that understands the essential appeal of what makes these movies more than “chick flicks.” Skip Love Again and its ilk and instead feel the pitter-patter of your heart renewed with Rye Lane.

Nate’s Grades:

Love Again: D+

Rye Lane: A-

All Quiet on the Western Front (2022)

The surprise surge of the Oscar season is a German-language remake of the 1929 Best Picture winner, and after watching all 140 minutes, it’s easy to see how it would have made such an impact with modern Academy voters. All Quiet on the Western Front is still a relevant story even more than 100 years after its events. It’s a shattering anti-war movie that continuously and furiously reminds you what a terrible waste of life that four-year battle over meters of territory turned out to be, claiming over 17 million casualties. I’ve read the 1928 German novel by Erich Remarque and the new movie is faithful in spirit and still breathes new life into an old story. We follow idealistic young men eager to experience the glory of war and quickly learn that the horror of modern combat isn’t so glorious. There are sequences in this movie that are stunning, like following the history of a coat from being lifted off a dead soldier in the muck, to being reworked at a seamstress station, to being commissioned to a new recruit who questions why someone else’s name is in his jacket. It’s a simple yet evocative moment that sells the despairing reality. The movie doesn’t skimp on carnage as well, as long stretches will often play out like a horror movie where you’ll fear the monsters awaiting in the smoke and that nowhere is safe for long. And yet, where the movie hits the hardest isn’t depicting the trenchant terror but with the little pieces of humanity that shine through the darkness. There’s a small moment in a crater shared by two enemies where one of them is dying, and these final moments of recognizing the same beleaguered helpless and frightened humanity of “their enemy” are poignant. Make no mistake, All Quiet is a condemnation on the systems of war where old pompous generals send young men to needlessly die for outdated and absurd reasons like the concept of “maintaining national honor.” A significant new subplot involves Daniel Bruhl (Captain America: Civil War) as a representative of the German government trying to negotiate an armistice when the French representatives are looking for punishment. It allows us to take a larger view of the politics that doomed so many and laying the foundation for so many more doomed lives. The ending of this movie is a nihilist gut punch. The production values are impressive and elevate the artistry of every moment. The sound design is terrific, the cinematography is alternatingly beautiful and horrifying, and the production design is startlingly detailed and authentic; it’s easy to see how this movie could have earned nine Oscar nominations. All Quiet on the Western Front is a warning, a eulogy, and a powerful reminder that even older stories can still be relevant and resonant.

The surprise surge of the Oscar season is a German-language remake of the 1929 Best Picture winner, and after watching all 140 minutes, it’s easy to see how it would have made such an impact with modern Academy voters. All Quiet on the Western Front is still a relevant story even more than 100 years after its events. It’s a shattering anti-war movie that continuously and furiously reminds you what a terrible waste of life that four-year battle over meters of territory turned out to be, claiming over 17 million casualties. I’ve read the 1928 German novel by Erich Remarque and the new movie is faithful in spirit and still breathes new life into an old story. We follow idealistic young men eager to experience the glory of war and quickly learn that the horror of modern combat isn’t so glorious. There are sequences in this movie that are stunning, like following the history of a coat from being lifted off a dead soldier in the muck, to being reworked at a seamstress station, to being commissioned to a new recruit who questions why someone else’s name is in his jacket. It’s a simple yet evocative moment that sells the despairing reality. The movie doesn’t skimp on carnage as well, as long stretches will often play out like a horror movie where you’ll fear the monsters awaiting in the smoke and that nowhere is safe for long. And yet, where the movie hits the hardest isn’t depicting the trenchant terror but with the little pieces of humanity that shine through the darkness. There’s a small moment in a crater shared by two enemies where one of them is dying, and these final moments of recognizing the same beleaguered helpless and frightened humanity of “their enemy” are poignant. Make no mistake, All Quiet is a condemnation on the systems of war where old pompous generals send young men to needlessly die for outdated and absurd reasons like the concept of “maintaining national honor.” A significant new subplot involves Daniel Bruhl (Captain America: Civil War) as a representative of the German government trying to negotiate an armistice when the French representatives are looking for punishment. It allows us to take a larger view of the politics that doomed so many and laying the foundation for so many more doomed lives. The ending of this movie is a nihilist gut punch. The production values are impressive and elevate the artistry of every moment. The sound design is terrific, the cinematography is alternatingly beautiful and horrifying, and the production design is startlingly detailed and authentic; it’s easy to see how this movie could have earned nine Oscar nominations. All Quiet on the Western Front is a warning, a eulogy, and a powerful reminder that even older stories can still be relevant and resonant.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022)/ Pinocchio (2022)

It seems 2022 has unexpectedly become the year of Pinocchio. The 1883 fantasy novel by Carlo Collodui (1826-1890) is best known via the classic Walt Disney animated movie, the second ever for the company, and it was Disney that released a live-action remake earlier in the year on their streaming service. Now widely available on Netflix is Guillermo del Toro’s stop-motion Pinocchio, so I wanted to review both films together but I was also presented with a unique circumstance. Both of these movies were adaptations of the same story, so the comparison is more direct, and I’ve decided to take a few cues from sports writing and break down the movies in a head-to-head competitive battle to see which has the edge in a series of five categories. Which fantastical story about a little puppet yearning to be a real boy will prove superior?

It seems 2022 has unexpectedly become the year of Pinocchio. The 1883 fantasy novel by Carlo Collodui (1826-1890) is best known via the classic Walt Disney animated movie, the second ever for the company, and it was Disney that released a live-action remake earlier in the year on their streaming service. Now widely available on Netflix is Guillermo del Toro’s stop-motion Pinocchio, so I wanted to review both films together but I was also presented with a unique circumstance. Both of these movies were adaptations of the same story, so the comparison is more direct, and I’ve decided to take a few cues from sports writing and break down the movies in a head-to-head competitive battle to see which has the edge in a series of five categories. Which fantastical story about a little puppet yearning to be a real boy will prove superior?

1. VISUAL PRESENTATION

The Netflix Pinocchio is a lovingly realized stop-motion marvel. It’s del Toro’s first animated movie and his style translates easily to this hand-crafted realm. There is something special about stop-motion animation for me; I love the tactile nature of it all, the knowledge that everything I’m watching is pain-stakingly crafted by artisans, and it just increases my appreciation. I fully acknowledge that any animated movie is the work of thousands of hours of labor and love, but there’s something about stop-motion animation that I just experience more viscerally. The level of detail in the Netflix Pinocchio is astounding. There is dirt under Geppetto’s fingernails, red around the eyes after crying, the folds and rolls of fabric, and the textures feel like you can walk up to the screen and run your fingers over their surfaces. I loved the character designs, their clean simplicity but able readability, especially the sister creatures of life and death with peacock feather wings, and the animation underwater made me question how they did what they did. del Toro’s imagination is not limited from animation but expanded, and there are adept camera movements that require even more arduous work to achieve and they do. I loved the life each character has, the fluidity of their movements, that they even animated characters making mistakes or losing their balance or acting so recognizably human and sprightly. There’s a depth of life here plus an added meta-textual layer about puppets telling the story about a puppet who was given life.

In contrast, the Disney live-action Pinocchio is harsh on the eyes. It’s another CGI smorgasbord from writer/director Robert Zemeckis akin to his mo-cap semi-animated movies from the 2000s. The brightness levels of the outside world are blastingly white, and it eliminates so much of the detail of the landscapes. When watching actors interact, it never overcomes the reality of it being a big empty set. The CGI can also be alarming with the recreation of the many animal sidekicks of the 1940 original. Why did Zemeckis make the pet goldfish look sultry? Why did they make Jiminy Cricket (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) look like a Brussel sprout come to life? It might not be the dead-eyed nightmare fuel of 2004’s The Polar Express, but the visual landscape of the movie is bleached and overdone, making everything feel overly fake or overly muddy and glum. The fact that this movie looks like this with a $150 million budget is disheartening but maybe inevitable. I suppose Zemeckis had no choice but to replicate the Pinocchio character design from 1940, but it looks remarkably out of step and just worse. When we have the 1940 original to compare to, everything in the 2022 remake looks garish or ugly or just wrong. The expressiveness of the hand-drawn animation is replaced with creepy-looking CGI animal-human hybrids.

In contrast, the Disney live-action Pinocchio is harsh on the eyes. It’s another CGI smorgasbord from writer/director Robert Zemeckis akin to his mo-cap semi-animated movies from the 2000s. The brightness levels of the outside world are blastingly white, and it eliminates so much of the detail of the landscapes. When watching actors interact, it never overcomes the reality of it being a big empty set. The CGI can also be alarming with the recreation of the many animal sidekicks of the 1940 original. Why did Zemeckis make the pet goldfish look sultry? Why did they make Jiminy Cricket (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) look like a Brussel sprout come to life? It might not be the dead-eyed nightmare fuel of 2004’s The Polar Express, but the visual landscape of the movie is bleached and overdone, making everything feel overly fake or overly muddy and glum. The fact that this movie looks like this with a $150 million budget is disheartening but maybe inevitable. I suppose Zemeckis had no choice but to replicate the Pinocchio character design from 1940, but it looks remarkably out of step and just worse. When we have the 1940 original to compare to, everything in the 2022 remake looks garish or ugly or just wrong. The expressiveness of the hand-drawn animation is replaced with creepy-looking CGI animal-human hybrids.

Edge: Netflix Pinocchio

2. FATHER/SON CHARACTERIZATION

The relationship between Pinocchio (voiced by Gregory Mann) and Geppetto (David Bradley) is the heart of the Netflix Pinocchio, and I don’t mind sharing that it brought me to tears a couple of times. As much as the movie is about a young boy learning about the world, it’s also about the love of a father for a child. The opening ten minutes establish Geppetto’s tragedy with such surefooted efficiency that it reminded me of the early gut punch that was 2009’s Up. This Geppetto is constantly reminded of his loss and, during a drunken fit, he carved a replacement child that happens to come to life. This boy is very different from his last, and there is a great learning curve for both father and son about relating to one another. This is the heart of the movie, one I’ll discuss more in another section. With del Toro’s version, Geppetto is a wounded and hurting man, one where every decision is connected to character. This Pinocchio is a far more entertaining creature, a child of explosive energy, curiosity, and spitefulness. He feels like an excitable newborn exploring the way of the world. He’s so enthusiastic so quickly (“Work? I love work, papa!” “I love it, I love it!… What is it?”) that his wonder can become infectious. This Pinocchio also cannot die, and each time he comes back to life he must wait longer in a netherworld plane. It provides even more for Pinocchio to understand about loss and being human. This is a funny, whimsical, but also deftly emotive Pinocchio. He points to a crucifix and asks why everyone likes that wooden man but not him. He is an outsider learning about human emotions and morals and it’s more meaningful because of the character investment.

In contrast, the Disney live-action Pinocchio treats its title character as a simpleton. The problem with a story about a child who breaks rules and learns lessons by dealing with the consequences of his actions is if you have a character that makes no mistakes then their suffering feels cruel. This Pinocchio is simply a sweet-natured wannabe performer. He means well but he doesn’t even lie until a sequence requires him to lie to successfully escape his imprisonment. The relationship with Geppetto (Tom Hanks) is strange. This kindly woodcarver is a widower who also has buried a son, but he comes across like a doddering old man who is quick to make dad jokes to nobody (I guess to his CGI cat and goldfish and multitude of Disney-tie-in cuckoo clocks). I don’t know what Hanks is doing with this daffy performance. It feels like Geppetto lost his mind and became stir crazy and this performance is the man pleading for help from the town, from the audience, from Zemeckis. It’s perplexing and it kept me from seeing this man as an actual character. He bounces from catalyst to late damsel in distress needing saving. The relationship between father and son lacks the warmth of the Netflix version. Yet again, the live-action Pinocchio is a pale imitation of its cartoon origins with either main character failing to be fleshed out or made new.

In contrast, the Disney live-action Pinocchio treats its title character as a simpleton. The problem with a story about a child who breaks rules and learns lessons by dealing with the consequences of his actions is if you have a character that makes no mistakes then their suffering feels cruel. This Pinocchio is simply a sweet-natured wannabe performer. He means well but he doesn’t even lie until a sequence requires him to lie to successfully escape his imprisonment. The relationship with Geppetto (Tom Hanks) is strange. This kindly woodcarver is a widower who also has buried a son, but he comes across like a doddering old man who is quick to make dad jokes to nobody (I guess to his CGI cat and goldfish and multitude of Disney-tie-in cuckoo clocks). I don’t know what Hanks is doing with this daffy performance. It feels like Geppetto lost his mind and became stir crazy and this performance is the man pleading for help from the town, from the audience, from Zemeckis. It’s perplexing and it kept me from seeing this man as an actual character. He bounces from catalyst to late damsel in distress needing saving. The relationship between father and son lacks the warmth of the Netflix version. Yet again, the live-action Pinocchio is a pale imitation of its cartoon origins with either main character failing to be fleshed out or made new.

Edge: Netflix Pinocchio

3. THEMES

There are a few key themes that emerge over the near two-hours of the Netflix Pinocchio, which is the longest stop-motion animated film ever. Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan McGregor) repeats that he “tried his best and that’s the best anyone can do,” and the parallelism makes it sound smarter than it actually is. The actual theme revolves around acceptance and the burdens of love. Geppetto cannot fully accept Pinocchio because he’s constantly comparing him to Carlo. When he can fully accept Pinocchio for who he is, the weird little kid with the big heart and unique perspective, is when he can finally begin to heal over the wound of his grief over Carlo, allowing himself to be vulnerable again and to accept his unexpected new family on their own terms. There’s plenty of available extra applications here to historically marginalized groups, and del Toro is an avowed fan of freaks and outcasts getting their due and thumbing their nose at the hypocritical moral authorities. By setting his story in 1930s Italy under the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini, del Toro underlines his themes of monsters and scapegoats and moral hypocrites even better, and the change of scenery really enlivens the familiar story with extra depth and resonance. All these different people want something out of Pinocchio that he is not. Geppetto wants him to strip away his individuality and be his old son. Count Volpe (Christoph Waltz) wants Pinocchio to be his dancing minion and secure him fame and fortune. Podesta (Ron Perlman) wants Pinocchio as the state’s ultimate soldier, a boy who cannot die and always comes back fighting. When Pinocchio is recruited to train for war with the other young boys to better serve the fatherland’s nationalistic aims, it’s a far more affecting and unsettling experience than Pleasure Island, which is removed from this version. In the end, the movie also becomes a funny and touching exploration of mortality from a magic little child. The Wood Sprite (Tilda Swinton), this version of the Blue Fairy, says she only wanted to grant Geppetto joy. “But you did,” he says. “Terrible, terrible joy.” The fleeting nature of life, as well as its mixture of pain and elation, is an ongoing theme that isn’t revelatory but still feels impressively restated.

I don’t know what theme the Disney live-action movie has beyond its identity as a product launch. I suppose several years into the Disney live-action assembly line I shouldn’t be surprised that these movies are generally listless, inferior repetitions made to reignite old company IP. For a story about the gift of life, the Disney Pinocchio feels so utterly lifeless. I thought the little wooden boy was meant to learn rights and wrongs but the movie doesn’t allow Pinocchio to err. He’s an innocent simpleton who gets taken advantage of and dragged from encounter to encounter like a lost child. The Pleasure Island sequence has been tamed from the 1940s; children are no longer drinking beer or smoking cigars. They’re gathered to a carnival and then given root beer and told to break items and then punished for this entrapment. The grief Geppetto feels for his deceased loved ones is played out like a barely conceived backstory. He’s just yukking it up like nothing really matters. By the end, when he’s begging for Pinocchio to come back to life, you wonder why he cares. If you were being quite generous, you might be able to uncover themes of acceptance and understanding, but they’re so poorly developed and utilized. That stuff gets in the way of Pinocchio staring at a big pile of horse excrement on the street, which if you needed a summative visual metaphor for the adaptation, there it is.

I don’t know what theme the Disney live-action movie has beyond its identity as a product launch. I suppose several years into the Disney live-action assembly line I shouldn’t be surprised that these movies are generally listless, inferior repetitions made to reignite old company IP. For a story about the gift of life, the Disney Pinocchio feels so utterly lifeless. I thought the little wooden boy was meant to learn rights and wrongs but the movie doesn’t allow Pinocchio to err. He’s an innocent simpleton who gets taken advantage of and dragged from encounter to encounter like a lost child. The Pleasure Island sequence has been tamed from the 1940s; children are no longer drinking beer or smoking cigars. They’re gathered to a carnival and then given root beer and told to break items and then punished for this entrapment. The grief Geppetto feels for his deceased loved ones is played out like a barely conceived backstory. He’s just yukking it up like nothing really matters. By the end, when he’s begging for Pinocchio to come back to life, you wonder why he cares. If you were being quite generous, you might be able to uncover themes of acceptance and understanding, but they’re so poorly developed and utilized. That stuff gets in the way of Pinocchio staring at a big pile of horse excrement on the street, which if you needed a summative visual metaphor for the adaptation, there it is.

Edge: Netflix Pinocchio

4. EMOTIONAL STAKES

One of these movies made me cry. The other one made me sigh in exasperation. The Netflix Pinocchio nails the characterization in a way that is universal and accessible while staying true to its roots, whereas the Disney live-action film feels like a crudely packaged remake on the assembly line of soulless live-action Disney remakes. By securing my investment early with Geppetto’s loss, I found more to relish in the layers of his relationship with Pinocchio. In trying to teach him about the world, Geppetto is relying upon what he started with his past son, and there are intriguing echoes that lead to a spiritual examination. Pinocchio is made from the tree from the pinecone that Carlo chased that lead to his death. Pinocchio hums the tune that Geppetto sang to Carlo. Is there something more here? When he visits Death for the first time, the winged creature remarks, “I feel as though you’ve been here before.” These little questions and ambiguity make the movie much more rewarding, as does del Toro’s ability to supply character arcs for every supporting player. Even the monkey sidekick of the villain gets their own character arc. Another boy desperately desires his stern father’s approval, and he’s presented as a parallel for Pinocchio, another son trying to measure up to his father’s demands. Even this kid gets meaningful character moments and an arc. With this story, nobody gets left behind when it comes to thoughtful and meaningful characterization. It makes the movie much more heartwarming and engaging, and by the end, as we get our poignant coda jumping forward in time and serving as multiple curtain calls for our many characters, I was definitely shedding a flurry of tears. Hearing Geppetto bawl, “I need you… my boy,” to the lifeless body of Pinocchio still breaks me. Under del Toro’s compassionate lens, everyone is deserving of kindness.

One of these movies made me cry. The other one made me sigh in exasperation. The Netflix Pinocchio nails the characterization in a way that is universal and accessible while staying true to its roots, whereas the Disney live-action film feels like a crudely packaged remake on the assembly line of soulless live-action Disney remakes. By securing my investment early with Geppetto’s loss, I found more to relish in the layers of his relationship with Pinocchio. In trying to teach him about the world, Geppetto is relying upon what he started with his past son, and there are intriguing echoes that lead to a spiritual examination. Pinocchio is made from the tree from the pinecone that Carlo chased that lead to his death. Pinocchio hums the tune that Geppetto sang to Carlo. Is there something more here? When he visits Death for the first time, the winged creature remarks, “I feel as though you’ve been here before.” These little questions and ambiguity make the movie much more rewarding, as does del Toro’s ability to supply character arcs for every supporting player. Even the monkey sidekick of the villain gets their own character arc. Another boy desperately desires his stern father’s approval, and he’s presented as a parallel for Pinocchio, another son trying to measure up to his father’s demands. Even this kid gets meaningful character moments and an arc. With this story, nobody gets left behind when it comes to thoughtful and meaningful characterization. It makes the movie much more heartwarming and engaging, and by the end, as we get our poignant coda jumping forward in time and serving as multiple curtain calls for our many characters, I was definitely shedding a flurry of tears. Hearing Geppetto bawl, “I need you… my boy,” to the lifeless body of Pinocchio still breaks me. Under del Toro’s compassionate lens, everyone is deserving of kindness.

As should be expected by now, the Disney live-action movie is lackluster at best when it comes to any kind of emotional investment. The characters stay as archetypes but they haven’t been personalized, so they merely remain as grubby facsimiles to what we recall from the 1940 version. Jiminy Cricket is meant as Pinocchio’s conscience but he vacillates from being a nag to being a smart aleck who even breaks the fourth wall to argue with his own narration. I hated every time he called the main character “Pee-noke” and he did it quite often. He’s far more annoying than endearing. There’s also a wise-cracking seagull that is just awful. The Honest John (Keegan Michael-Key) character is obnoxious, and in a world with a talking fox who dresses in human clothing, why would a “living puppet” be such a draw? He even has a joke about Pinocchio being an “influencer.” The only addition I liked was a coworker in Stromboli’s traveling circus, a former ballerina who injured herself and now gets to live out her dancing dreams by operating a marionette puppet. However, the movie treats the puppet like it’s a living peer to Pinocchio and talks directly to the puppet rather than the human operating the puppet, and the camera treats her like she’s the brains too. Safe to say, by the end when Pinocchio magically revives for whatever reason, just as he magically reverted from being a donkey boy, I was left coldly indifferent and more so just relieved that the movie was finally over.

Edge: Netflix Pinocchio

5. MUSIC

This was one area where I would have assumed the Disney live-action film had an advantage. Its signature banger, “When You Wish Upon a Star,” became the de facto Disney theme song and plays over the opening title card for the company. It’s still a sweet song, and Cynthia Erivo (Harriet) is the best part of the movie as the Blue Fairy. It’s a shame she only appears once, which is kind of negligent considering she sets everything in motion. The Netflix Pinocchio is also a musical and the songs by Alexandre Desplat (The Shape of Water) are slight and low-key, easy to dismiss upon first listen. However, the second time I watched the movie, the simplicity as a leitmotif really stood out, and I noticed the melody was the foundation for most other songs, which created an intriguing interconnected comparison. While nothing in the Netflix Pinocchio comes close to being the instantly humable classic of “When You Wish Upon a Star,” the songs are more thoughtful and emotionally felt and not just repeating the hits of yore, so in the closest of categories, I’m going to say that Netflix’s Pinocchio wins by a nose (pun intended).