Blog Archives

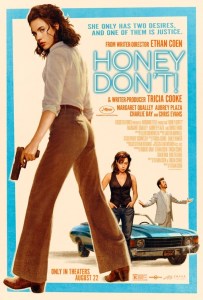

Honey Don’t (2025)

It’s the second collaboration between Ethan Coen and his wife Tricia Cooke and reportedly the second in their “B-movie lesbian trilogy” (the planned third film is tentatively titled Go Beavers). It’s better than 2024’s Drive-Away Dolls, a randy cartoon that was so overpowering and underwhelming. This time the filmmakers play around in the film noir genre with Margaret Qualley as a wily private eye, Honey O’Donahue. The whodunnit plot is a series of disconnected threads and plotlines that don’t connect together in interesting or surprising ways. It begins with an immediate mystery: a woman, dressed right out of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, walking down an embankment to inspect an overturned auto and the body inside. Boom. I’m intrigued right away. Sadly, this might be the high point. A third of Honey Don’t involves Chris Evans playing a debauched minister selling drugs on the side and exploiting his congregation. His storyline seems to run in parallel with Honey’s investigation without really crossing in meaningful ways. It even resolves without her intervention. It’s also incredibly dull and repetitive, with Evans’ reverend being interrupted during sex multiple times for comedy, I guess. Honey Don’t exists as a winky flip on the noir genre, this time with lesbians! It doesn’t so much feel like a compelling story with colorful characters as it does a writing exercise. Qualley fares better as the straight-laced yet flirty private eye than she did as the horny caricature in Drive-Away Dolls. She’s got a self-possessed charisma and determination that works. If only the rest of the movie didn’t repeatedly let her down. It’s not offensively bad, or even as aggressively cringey as their previous collaboration, but Honey Don’t is another middling, daffy, disposable genre riff by Ethan Coen that makes me long for an eventual reunion with his brother.

It’s the second collaboration between Ethan Coen and his wife Tricia Cooke and reportedly the second in their “B-movie lesbian trilogy” (the planned third film is tentatively titled Go Beavers). It’s better than 2024’s Drive-Away Dolls, a randy cartoon that was so overpowering and underwhelming. This time the filmmakers play around in the film noir genre with Margaret Qualley as a wily private eye, Honey O’Donahue. The whodunnit plot is a series of disconnected threads and plotlines that don’t connect together in interesting or surprising ways. It begins with an immediate mystery: a woman, dressed right out of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!, walking down an embankment to inspect an overturned auto and the body inside. Boom. I’m intrigued right away. Sadly, this might be the high point. A third of Honey Don’t involves Chris Evans playing a debauched minister selling drugs on the side and exploiting his congregation. His storyline seems to run in parallel with Honey’s investigation without really crossing in meaningful ways. It even resolves without her intervention. It’s also incredibly dull and repetitive, with Evans’ reverend being interrupted during sex multiple times for comedy, I guess. Honey Don’t exists as a winky flip on the noir genre, this time with lesbians! It doesn’t so much feel like a compelling story with colorful characters as it does a writing exercise. Qualley fares better as the straight-laced yet flirty private eye than she did as the horny caricature in Drive-Away Dolls. She’s got a self-possessed charisma and determination that works. If only the rest of the movie didn’t repeatedly let her down. It’s not offensively bad, or even as aggressively cringey as their previous collaboration, but Honey Don’t is another middling, daffy, disposable genre riff by Ethan Coen that makes me long for an eventual reunion with his brother.

Nate’s Grade: C

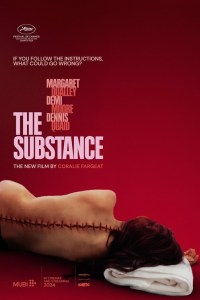

The Substance (2024)

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

In 2017, French filmmaker Coralie Fargeat released her debut movie, Revenge, her daring spin on the rape-revenge thriller. It was an immediate notice that this filmmaker could take any genre and spin it on its head, providing feminist influences on some of the most grisly and male-dominated exploitation cinema. Even more so, she makes whatever genre her own and on her own terms. The same can be said for The Substance, a movie that utilizes sensationalism to sensational effect. It’s a movie that is far more than the sum of its Frankenstein-esque body horror parts.

Elisabeth (Demi Moore) is a television fitness instructor who has been massively popular for decades. Upon her 50th birthday, she’s promptly dismissed from her job by her studio, concerned over her diminished appeal as a sex symbol. She gets word of a mysterious elixir that can help her reverse the ravages of aging. It arrives via a clandestine P.O. box in a container with syringes and very specific instructions. She needs to spend seven days as her younger self, and seven days as her present self. She needs to “feed” her non-primary self. She also needs to understand that she is still the same person and not to get confused. Elisabeth injects herself with the serum and, through great physical duress, “Sue” emerges from her back like a butterfly sprouting from a fleshy cocoon. As Sue (Margaret Qualley), she’s now able to bask in the fame and attention that had been drifting away. Sue becomes the next hot fitness instructor and everything the studio wants. Except she’s enjoying being Sue so much that going back to her Elisabeth self feels like a punishment. Sue/Elisabeth starts to cheat the very specific rules of substance-dom, and some very horrifying results will transpire as she becomes increasingly desperate to hold onto what she has gained.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

Let me start off this review looking at the substance of The Substance, particularly the criticism that there is little below its surface-level charms. First off, let me defend surface-level charms when it comes to movies. It’s a visual medium, and sometimes the surface can be plenty when we’re dealing with artists at the top of their game. Being transported and entertained can be enough from a movie. Not every film needs to force you to re-evaluate the human condition. It’s perfectly acceptable for films to just be diversionary appeals to the senses. With that being said, the simplicity of the movie’s story and themes works to its benefit. The plotting is very clear, setting aside the rules, and then we watch the spiraling consequences when Elisabeth, and then Sue, decide to go against the rules and pay dearly. The ease of the storytelling is so precise with its cause-effect escalation, so that even when things are getting crazy, we know why. The commentary on aging in Hollywood isn’t new or subtle; yes, the industry treats young women like products to be exploited for mass consumption until they get older and are seen as less desirable. Yes, the pressure to fight the irreversible pull of aging can lead to increasingly desperate actions. Yes, being forced to cede the spotlight to someone you feel inferior can be humiliating. It’s nothing new, but it presents an effective foundation for what becomes a highly engaging, garishly repellent, and jubilantly visceral body horror deconstruction into madness. Rarely do we get an opportunity to say a movie must be seen to be believed, and The Substance is that latest must-see spectacle.

I found the exploration of identity between Sue and Elisabeth to be really interesting, as we’re told repeatedly in the instructions that the two are the same person, and yet the two versions view the other with increasing resentment and hostility. For all intents and purposes, it’s the same woman trying on different outfits of herself, but that doesn’t stop the dissociation. In short order, the two versions view one another as rivals fighting over a shared resource/home. Sue becomes the preferred version and thus the “good times” where she can feel at her best. The older Elisabeth persona then becomes the unwanted half, and the weeks spent outside the coveted persona are akin to a depression. She keeps to herself, gorges on junk food, and anxiously counts the prolonged hours until she can finally transform into Sue. Again, this is the same character, but when she’s wearing the younger woman’s body, it can’t help but trick her into feeling like a different person. This division builds a fascinating antagonism ultimately against herself. She’s literally fighting with herself over her own body, and that sounds like pertinent social commentary to me.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

While The Substance might not have much to say about aging and Hollywood that hasn’t been said before, where the movie separates itself from the pack is through the power of its voice. This is a movie that announces itself at every turn; it is a loud, emphatic personality that can take your breath away one moment and leave you riotously laughing the next. The vision and filmmaking voice of this movie is unmistakable, and while we’re covering familiar thematic ground on its many subjects, the director is assuring us, “Yes, but you haven’t seen my version,” and after a few minutes, I wanted to see wherever Fargeat wanted to take me. I loved the very opening sequence that catalogues our star’s career through a time lapse shot of her Hollywood Walk of Fame star. We see the public unveiling, arguably the height of her stardom, and then progress further, from tourists taking their picture with the star, to people ignoring it, a passing dog peeing over it, and a homeless shopping cart wheeling over it. In one shot, Fargeat has already efficiently told our character’s rise and fall through imaginative and accessible visuals. There are other elements like this throughout that kept me glued to the screen, eager to see the director’s take on the material.

This is a first-rate body horror parable with wonderfully surreal touches throughout. The creation of Sue, being born from ripping from Elisabeth’s back, is an evocative and shocking image, as is the garish stapling of Elisabeth’s back/entry wound (why it makes for the poster’s key image). It’s reminiscent of a snake slithering out of its old skin, but to also have to take care of that old skin, knowing you have to metaphorically slide it back on, is another matter entirely. The literal dead weight is a reminder of the toll of this process but it’s also like they’ve been given a dependant. The spinal fluid injections are another squirm factor. I loved the way the Kubrickian production design heightens the unreality of the world. I won’t spoil where exactly the movie goes, but know that very bad things will happen beyond your wildest predictions. The finale is a tremendously bonkers climax that fulfills the gonzo, blood-soaked madness of the movie. If you’re a fan of inspired and disturbing body horror, The Substance cannot be missed.

Demi Moore is a fascinating selection for our lead. While it might have been inspired to have Qualley (Maid, Kinds of Kindness) play the younger version of her mother, Andie McDowell (Groundhog Day), it’s meaningful to have Moore as our aging figure of beauty standards. Here is an actress who has often been defined by her body, from the record payday she got for agreeing to bare it all in 1996’s Striptease, to the iconic Vanity Fair magazine cover of her nude and pregnant, to the roles where men are fighting over her body (Indecent Proposal), she’s using her body to tempt (Disclosure), or she’s using her body to push boundaries (G.I. Jane). It’s also meaningful that Moore has been out of the limelight for some time, mimicking the predicament for Elisabeth. Because of her personal history, the character has more meaning projected onto her, and Moore’s performance is that much richer. It reminded me of Nicolas Cage’s performance in Pig, a statement about an artist’s career that has much more resonance because of the years they can parlay into the lived-in role. Moore is fantastic here as our human face to the pressures and psychological torment of aging. She has less and less to hold onto, and in the later stretches of the movie, while Moore is buried under mountains of mutation makeup, she still manages to show the scared person underneath.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Qualley has more screen time in the second half of the movie and has the challenge of playing a very specific kind of character. Sue is the idealized form for Elisabeth which makes her character even more exaggerated and surreal. She’s a figure of pure id, strutting her stuff because she can, luxuriating in the sense of power she has because of the desire that she produces. Qualley goes full hyper-sexualized cartoon for the beginning part of the role, where she’s the coveted version riding high. It’s the second half, where things begin to slip away, that Qualley shines the most as the cracks begin to take hold in this carefully arranged persona of confidence.

Much needs to be said about the hyperbolic sexualization of its characters, particularly Sue as the new young fitness star. Obviously our director is intending to satirize the default male gaze of the industry, as her camera lingers over tawny body parts and close-ups of curves, crevices, and crotches. However, the sexual satire is so ridiculously exploitative that it passes over from being too much and back to the sheer overkill being the point. This is not a movie of subtlety and instead one of intensity to the point that most would turn back and say, “That’s enough now.” For a movie about the perils and pleasures of the flesh, it makes sense for the photography to be as amplified in its rampant sensuality. There are segments where every camera angle feels like a thirsty glamour shot to arouse or arrest, but again this is done for a reason, to showcase Elisabeth/Sue as the world values them. The over-the-top male gaze the movie applies can be overpowering and exhausting, but I think that’s exactly Fargeat’s point: it’s reductive, insulting, and just exhausting to exclusively view women on these narrow terms. This isn’t quite our world, as the number one show on TV is an aerobics instructor, but it’s still close enough. I can understand the tone being too much for many viewers, but if you can push through, you might see things the way Fargeat does, and every lingering and exaggerated beauty shot might make you chuckle. It’s body horror on all fronts, showing the grotesquery not just in how bodies degrade but how we degrade others’ bodies.

On a personal note, while I’ll be back-dating this review, I wrote portions of it while sitting at my father’s bedside during his last days of life. He’s the person that instilled in me the love of movies, and I learned from him the shared language of cinematic storytelling, and one of my regrets is that I didn’t go see more movies with my father while we could. I really wish he could have seen The Substance because he was always hungry for new experiences, to be wowed by something he felt like he hadn’t quite seen before, to be transported to another world. He was also a fan of dark humor, ridiculous plot twists, and over-the-top violence, and I can hear his guffawing in my head now, thinking about him watching The Substance in sustained rapturous entertainment. It’s a movie that evokes strong feelings, chief among them a compulsive need to continue watching. It’s more than a body horror movie but it’s also an excellent body horror movie. Fargeat has established herself, in two movies, as an exciting filmmaker choosing to work within genre storytelling, reusing the tools of others to claim as her own with a proto-feminist spin and an absurdist grin. The Substance is the kind of filmgoing experience so many of us crave: vivid and unforgettable. And, for my money, the grossest image in the whole movie is Dennis Quaid slurping down shrimp.

Nate’s Grade: A

Kinds of Kindness (2024)

Yorgos Lanthimos might be one of the strangest filmmakers ever to fall into favor with the Oscars. Hot off the critical and commercial success of 2023’s Poor Things, we have a new Lanthimos joint not even six months later. This is a collaboration between his Greek co-writer from The Lobster and The Killing of a Sacred Deer, arguably the less “mainstream” Lanthimos movies. This movie is an anthology of three stories with the same actors playing different roles in each story. The problem is that I didn’t engage with any of the stories and found them long, meandering, and poorly paced. That Lanthimos specialty is a cracked-mirror version of the world, mixing the bizarre as if it were mundane, and it’s a trying tonal tightrope for most thespians to excel within that space. There just isn’t enough here, and each new story feels like starting over rather than fulfilling a conclusion. The prior Lanthimos movies had an interesting premise or turn of events that could sustain a whole movie; Kinds of Kindness doesn’t have stories that can sustain three vignettes. I can take weird, alienating, and challenging Lanthimos, as I’ve been a fan ever since his Dogtooth debut, but this is easily his weakest movie yet. The actors all do credible work having distaff conversations in, what appears like, people’s palatial homes and doctor offices. It’s hard to glean a larger theme, point of view, or even general entertainment value with this dull entry. It feels like Lanthimos and his collaborators had a couple free weekends, the use of some rich friends’ homes, and said, “Well, we’ll make it an anthology because then we don’t have to compose a full movie.” Instead of one disappointing movie, now you get three. Kinds of Kindness is, worst of all, mostly forgettable, and given Lanthimos’ track record, that really is the biggest sin possible.

Nate’s Grade: C

Drive-Away Dolls (2024)

Drive-Away Dolls is an interesting curiosity, not just for what it is but also for what it is not. It’s the first movie directed solo by Ethan Coen, best known as one half of the prolific filmmaking Coen Brothers, who have ushered in weird and vibrant masterpieces across several genres. After 2018’s The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, their last collaboration, the brothers decided to set out on their own for an unspecified amount of time. This led Joel Coen to direct 2021’s atmospheric adaptation of Macbeth, and now Ethan has decided that the fictional movie he really wants to make, unshackled by his brother, is a crass lesbian exploitation sex comedy. Well all right then.

Drive-Away Dolls is an interesting curiosity, not just for what it is but also for what it is not. It’s the first movie directed solo by Ethan Coen, best known as one half of the prolific filmmaking Coen Brothers, who have ushered in weird and vibrant masterpieces across several genres. After 2018’s The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, their last collaboration, the brothers decided to set out on their own for an unspecified amount of time. This led Joel Coen to direct 2021’s atmospheric adaptation of Macbeth, and now Ethan has decided that the fictional movie he really wants to make, unshackled by his brother, is a crass lesbian exploitation sex comedy. Well all right then.

Set in 1999 for some reason, Jamie (Margaret Qualley) is an out lesbian who unabashedly seeks out her own pleasures, even if it brings about the end of her personal relationships. Her friend, Marian (Geraldine Viswanathan), hasn’t had a lover in over three years and is much more prim and proper. Together, these gal pals decide to drive to Tallahassee, Florida using a drive-away service, where they will be paid to drive one way, transporting a used car. It just so happens that these women have mistakenly been given the wrong car, a vehicle intended for a group of criminals transporting contraband that they don’t want exposed. Jamie is determined to get laid and help Marian get laid all the while goons (Joey Slotnick, C.J. Wilson) are trailing behind to nab the ladies before they discover the valuable contents inside the trunk of their car.

Drive-Away Dolls is clearly an homage to campy 1970s exploitation B-movies but without much more ambition than making a loosey-goosey vulgar comedy consumed by the primal pursuit of sexual pleasure. I was genuinely surprised just how radiantly horny this movie comes across, with every scene built in some way upon women kissing, women having sex, women talking about having sex, women pleasuring themselves, women talking about pleasuring themselves, and women talking about pleasuring other women. When I mean every scene I mean virtually every scene in this movie, as the thinnest wisp of a road trip plot is barely holding together these scenes. From a representational standpoint, why shouldn’t lesbians have a raunchy sex comedy that is so open about these topics and demonstrates them without shame? Except it feels like the crude subject matter is doing all the heavy lifting to make up for the creative shortcomings elsewhere in the movie, which, sadly there are many. The script is co-written by Coen and his wife of many years, Tricia Cooke, an out lesbian, so it feels like the intent is to normalize sex comedy tropes for queer women, but the whole movie still feels overwhelming in the male gaze in its depictions of feminine sexuality. I’m all for a sex-positive lesbian road trip adventure, but much of the script hinges upon the uptight one learning to love sex, which means much of the story is dependent upon the promiscuous one trying to then bed her longtime friend and get her off. Rather than feel like some inevitability, the natural conclusion of a friendship that always had a little something more under the surface, it feels more like a horny and calculated math equation (“If you have two gay female leads, you can get them both kissing women by having them kiss each other”).

Drive-Away Dolls is clearly an homage to campy 1970s exploitation B-movies but without much more ambition than making a loosey-goosey vulgar comedy consumed by the primal pursuit of sexual pleasure. I was genuinely surprised just how radiantly horny this movie comes across, with every scene built in some way upon women kissing, women having sex, women talking about having sex, women pleasuring themselves, women talking about pleasuring themselves, and women talking about pleasuring other women. When I mean every scene I mean virtually every scene in this movie, as the thinnest wisp of a road trip plot is barely holding together these scenes. From a representational standpoint, why shouldn’t lesbians have a raunchy sex comedy that is so open about these topics and demonstrates them without shame? Except it feels like the crude subject matter is doing all the heavy lifting to make up for the creative shortcomings elsewhere in the movie, which, sadly there are many. The script is co-written by Coen and his wife of many years, Tricia Cooke, an out lesbian, so it feels like the intent is to normalize sex comedy tropes for queer women, but the whole movie still feels overwhelming in the male gaze in its depictions of feminine sexuality. I’m all for a sex-positive lesbian road trip adventure, but much of the script hinges upon the uptight one learning to love sex, which means much of the story is dependent upon the promiscuous one trying to then bed her longtime friend and get her off. Rather than feel like some inevitability, the natural conclusion of a friendship that always had a little something more under the surface, it feels more like a horny and calculated math equation (“If you have two gay female leads, you can get them both kissing women by having them kiss each other”).

I’m sad to report that Drive-Away Dolls is aggressively unfunny and yet it tries so hard. It’s the kind of manic, desperate energy of an improv performer following an impulse that was a mistake but you are now watching the careening descent into awkward cringe and helpless to stop. The movie is so committed to its hyper-sexual goofball cartoon of a world, but rarely does any of it come across as funny or diverting. When Jamie’s ex-girlfriend Suki (Beanie Feldstein) is trying to remove a dildo drilled onto her wall, she screams in tears, “I’m not keeping it if we both aren’t going to use it.” The visual alone, an ex in tears removing all the sexual accoutrements of her previous relationship, some of which can be widely over-the-top, could be funny itself. However, when her reasoning is that we both can’t use this any longer, then the line serves less as a joke and more a visual cue for the audience to think about both of them taking turns. It doesn’t so much work at being funny first and rather as a horny reminder of women being sexual together. The same with a college soccer team’s sleepover that literally involves a basement make-out party with a timer going off and swapping partners. It’s not ever funny but features plenty of women making out with one another to satisfy some audience urges. I will admit it serves a plot purpose of first aligning Jamie and Marian into awkwardly kissing one another, thus sparking carnal stirrings within them.

My nagging issue with the movie’s emphasis is not a puritanical response to vulgar comedy but that this movie lacks a necessary cleverness. It doesn’t really even work as dumb comedy, although there are moments that come close, like the absurd multiple-corkscrew murder that opens the movie. It’s just kind of exaggerated nonsense without having the finesse to steer this hyper-sexual world of comedy oddballs. The crime elements clash with the low-stakes comedy noodling of our leads bumbling their way through situation after situation that invariably leads to one of them undressing or inserting something somewhere. The brazen empowerment of women seeking out pleasure is a fine starting point for the movie, but the characters are too weakly written as an Odd Couple match that meets in the middle, the uptight one learning to loosen up and the irresponsible one learning to be less selfish. The goons chasing them are a pale imitation of other famous Coen tough guys; they lack funny personality quirks to broaden them out. There’s a conspiracy exposing political hypocrites condemning the “gay agenda,” and I wish more of this was satirized rather than a briefcase full of reportedly famous phalluses. If you got a briefcase full of famous appendages, I was expecting more jokes than blunt objects.

My nagging issue with the movie’s emphasis is not a puritanical response to vulgar comedy but that this movie lacks a necessary cleverness. It doesn’t really even work as dumb comedy, although there are moments that come close, like the absurd multiple-corkscrew murder that opens the movie. It’s just kind of exaggerated nonsense without having the finesse to steer this hyper-sexual world of comedy oddballs. The crime elements clash with the low-stakes comedy noodling of our leads bumbling their way through situation after situation that invariably leads to one of them undressing or inserting something somewhere. The brazen empowerment of women seeking out pleasure is a fine starting point for the movie, but the characters are too weakly written as an Odd Couple match that meets in the middle, the uptight one learning to loosen up and the irresponsible one learning to be less selfish. The goons chasing them are a pale imitation of other famous Coen tough guys; they lack funny personality quirks to broaden them out. There’s a conspiracy exposing political hypocrites condemning the “gay agenda,” and I wish more of this was satirized rather than a briefcase full of reportedly famous phalluses. If you got a briefcase full of famous appendages, I was expecting more jokes than blunt objects.

I feel for the actors, so eager to be part of a Coen movie, even if it’s only one of them and even if it’s something much much lesser. Qualley (Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood) is a typical Coen cartoon of a character, complete with peculiar accent and syntax. She’s going for broke with this performance but the material, time and again, requires so little other than being exaggerated and horny. There is one scene where her physical movements are so broad, so heightened to the point of strain, that I felt an outpouring of pity for her. It feels like a performance of sheer energetic force lacking proper direction. Viswanathan has been so good in other comedies and she’s given so little to do here other than playing the straight women (no pun intended) to Qualley’s twangy cartoon. Her portrayal of sexual coming of age and empowerment was better realized, and funnier, in 2018’s Blockers, a superior sex-positive sex comedy.

As a solo filmmaker, Ethan Coen seems to confirm that his brother is more the visual stylist of the duo. The movie is awash in neon colors and tight closeups of bug eyes and twangy accents, but the most annoying stylistic feature, by far, is the repeated psychedelic transition shots, these trippy interstitials that don’t really jibe with anything on screen. It felt like padding for an already stretched-thin movie that can barely reach 75 minutes before the end credits kick in. That’s why the extended sequences where the intention seems exploitation elements first and comedy second, or third, or not at all, makes the whole enterprise feel like a pervy curiosity that has its empowering yet obvious message of “girls do it too” as cover. Agreed, but maybe do more with the material beyond showcasing it. Ethan Coen is a prolific writer who has written short story collections (I own his 1998 book Gates of Eden), poetry collections, and he even wrote five one-act plays before the pandemic struck in 2020. I’d love to see those plays. This man has true talent but it’s just not obviously present throughout this film.

As a solo filmmaker, Ethan Coen seems to confirm that his brother is more the visual stylist of the duo. The movie is awash in neon colors and tight closeups of bug eyes and twangy accents, but the most annoying stylistic feature, by far, is the repeated psychedelic transition shots, these trippy interstitials that don’t really jibe with anything on screen. It felt like padding for an already stretched-thin movie that can barely reach 75 minutes before the end credits kick in. That’s why the extended sequences where the intention seems exploitation elements first and comedy second, or third, or not at all, makes the whole enterprise feel like a pervy curiosity that has its empowering yet obvious message of “girls do it too” as cover. Agreed, but maybe do more with the material beyond showcasing it. Ethan Coen is a prolific writer who has written short story collections (I own his 1998 book Gates of Eden), poetry collections, and he even wrote five one-act plays before the pandemic struck in 2020. I’d love to see those plays. This man has true talent but it’s just not obviously present throughout this film.

Drive-Away Dolls is an irreverent sex comedy with good intentions and bad ideas, or good ideas and bad intentions, an exploitation picture meant to serve as empowerment but still presents its world as exploitation first and last. It’s just not a funny movie, and it’s barely enough to cover a full feature. I suppose one could celebrate its mere existence as an affront to those puritanical forces trying to oppress feminine sexuality, but then you could say the same thing about those 1970s women-in-prison exploitation pictures. It’s a strange movie experience, achingly unfunny, overly mannered, and makes you long for the day that the two Coens will reunite and prove that the two men are better as a united creative force; that’s right, two Coens are better than one.

Nate’s Grade: C-

You must be logged in to post a comment.