Blog Archives

Didi (2024)

It feels slightly strange when you acknowledge that coming-of-age movies have long-surpassed your own age of adolescent personal discovery. With Sundance indie Didi, we’ve now brought that time frame up to 2008, where we follow the 13-year-old Chris (Izac Wang), a first-generation Taiwanese-American kid trying to flirt with his junior high crush, get better at skateboarding, edit YouTube videos that people might actually want to see, and perhaps make some new friends during the summer before high school begins. This is one of those movies that lives or dies by its slice-of-life details and sense of authenticity. Writer/director Sean Wang does an excellent job placing the audience in the position of his biographical avatar, Chris. We feel his discomfort trying to navigate the different cultural expectations of home life and school life, the perils of trying to step outside your comfort zone and be rewarded rather than embarrassed. This is compounded by Chris having to endure and brush aside the stereotypes his peers project onto him for being Asian-American. The problem with the movie is that our main character is kind of a twit. He’s so harsh and unfair to his long-suffering mother (Lust, Caution‘s Joan Chen) that his own friends eventually complain about his rude behavior. In a moment of awkward discomfort, he calls his friend’s crush “a whore,” and then describes how he and his friend messed around with the corpse of a squirrel once. He also pees in his older sister’s lotion bottle. The whole “befriending cool skateboarders” storyline goes nowhere, nor does it open up some deeper understanding of our character and his wants, talents, or capabilities. Didi’s real distinct angle could have been growing up in the Internet age, and there it too feels lacking. It all feels a little like we’re spending too much time with the wrong family member. The put-upon mother would have been an even more intriguing person to explore, especially as she yearns to be an artist, deals with her bratty kids, an overbearing mother-in-law living with them without a kind word to say, and a husband half the world away busy working. Getting stuck with the angsty kid feels disappointing.

It feels slightly strange when you acknowledge that coming-of-age movies have long-surpassed your own age of adolescent personal discovery. With Sundance indie Didi, we’ve now brought that time frame up to 2008, where we follow the 13-year-old Chris (Izac Wang), a first-generation Taiwanese-American kid trying to flirt with his junior high crush, get better at skateboarding, edit YouTube videos that people might actually want to see, and perhaps make some new friends during the summer before high school begins. This is one of those movies that lives or dies by its slice-of-life details and sense of authenticity. Writer/director Sean Wang does an excellent job placing the audience in the position of his biographical avatar, Chris. We feel his discomfort trying to navigate the different cultural expectations of home life and school life, the perils of trying to step outside your comfort zone and be rewarded rather than embarrassed. This is compounded by Chris having to endure and brush aside the stereotypes his peers project onto him for being Asian-American. The problem with the movie is that our main character is kind of a twit. He’s so harsh and unfair to his long-suffering mother (Lust, Caution‘s Joan Chen) that his own friends eventually complain about his rude behavior. In a moment of awkward discomfort, he calls his friend’s crush “a whore,” and then describes how he and his friend messed around with the corpse of a squirrel once. He also pees in his older sister’s lotion bottle. The whole “befriending cool skateboarders” storyline goes nowhere, nor does it open up some deeper understanding of our character and his wants, talents, or capabilities. Didi’s real distinct angle could have been growing up in the Internet age, and there it too feels lacking. It all feels a little like we’re spending too much time with the wrong family member. The put-upon mother would have been an even more intriguing person to explore, especially as she yearns to be an artist, deals with her bratty kids, an overbearing mother-in-law living with them without a kind word to say, and a husband half the world away busy working. Getting stuck with the angsty kid feels disappointing.

Nate’s Grade: B-

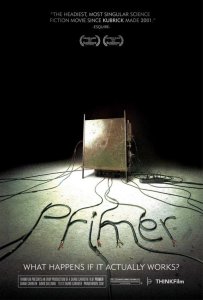

Primer (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released October 8, 2004:

Originally released October 8, 2004:

I was intrigued about Primer because I had been told it was classy, smart sci-fi that’s so often missing in today’s entertainment line-up (see: Sci-Fi channel’s Mansquito). It won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival and the critical reviews had been generally very positive. So my expectations were high for a well wrought, high brow film analyzing time travel. What I got was one long, pretentious, incomprehensible, poorly paced and shot techno lecture. Oh it got bad. Oh did it get bad.

Aaron (Shane Carruth) and Abe (David Sullivan) run a team of inventors out of their garage. Their newest invention seems promising but they’re still confused about what it does. Aaron and Abe’s more commercially minded partners want to patent it and sell it. Aaron and Abe inspect their invention further and discover it has the ability to distort time. They invent larger versions and time travel themselves and thus create all kinds of paradoxes and loops and confusion for themselves and a viewing audience.

Watching Primer is like reading an instruction manual. The movie is practically crushed to death by techno terminology and all kinds of geek speak. The only people that will be able to follow along are those well-versed in quantum physics and engineering. Indeed, Primer has been called an attempt to make a “realistic time-travel movie,” which means no cars that can go 88 miles per hour. That’s fine and dandy but it makes for one awfully boring movie.

Primer would rather confound an audience than entertain them. There is a distinct difference between being complicated and being hard to follow. You’d need a couple volumes of Cliff Notes just to follow along Primer‘s talky and convoluted plot. I was so monumentally bored by Primer that I had to eject the DVD after 30 minutes. I have never in my life started a film at home and then turned it off, especially one I paid good money to rent, but after so many minutes of watching people talk above my head in a different language (techno jargon) I had reached my breaking point. Primer will frustrate most viewers because most will not be able to follow what is going on, and a normal human being can reasonably only sit for so long in the dark.

Primer would rather confound an audience than entertain them. There is a distinct difference between being complicated and being hard to follow. You’d need a couple volumes of Cliff Notes just to follow along Primer‘s talky and convoluted plot. I was so monumentally bored by Primer that I had to eject the DVD after 30 minutes. I have never in my life started a film at home and then turned it off, especially one I paid good money to rent, but after so many minutes of watching people talk above my head in a different language (techno jargon) I had reached my breaking point. Primer will frustrate most viewers because most will not be able to follow what is going on, and a normal human being can reasonably only sit for so long in the dark.

I did restart Primer and watched it to its completion, a scant 75 minutes long. The last 20 minutes is easier to grasp because it does finally deal with time travel and re-staging events. It’s a very long time to get to anything comprehensible. I probably should watch Primer again in all fairness but I have the suspicion that if I did my body would completely shut down on me in defense. Some people will love this and call it visionary, but those will be a very select group. It’s not just that Primer is incomprehensible but the film is also horrifically paced. When you don’t know what’s being said and what’s going on then scenes tend to drag because there is no connection. This movie is soooooo slow and it’s made all the worse by characters that are merely figureheads, dialogue that’s confusing and wooden, and a story that would rather spew ideas than a plot.

Writer/director/star Shane Carruth seems to have high ambitions but he has no empathy for an audience. Films can be dense and thought-provoking but they need to be accessible. Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is a sci-fi mind bender but it’s also an accessible, relatable, enjoyable movie that’s become a cult favorite. Carruth also seems to think that shooting half the movie out of focus is a good idea.

I’m not against a smart movie, nor am I against science fiction that attempts to explore profound concepts and ideals. What I am against, however, is wasting my time with a tech lecture disguised as quality entertainment. Primer is obtuse, slow, convoluted, frustrating and pretentiously impenetrable. After finally finishing Primer, I scanned the DVD spine and noticed it said, “Thriller.” I laughed so hard I almost fell over. The only way Primer could be a thriller is because you’ll be racing the clock for it to finish.

Nate’s Grade: C-

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I tried, dear reader. I had every intention of giving 2004’s Primer another chance, wanting to allow the distance of time to perhaps make the movie more palatable for my present-day self than it was when I was in my early twenties and irritated by this low-budget, high-concept Sundance DIY time travel indie. I thought with two decades of hindsight, I’d be able to find the brilliance that people cited back in 2004 where instead I only found maddening frustration. I consider myself a relatively intelligent individual, so I felt like I would be able to unpack what has been dubbed the most complex and realistic time travel movie ever created, let alone on a shoestring budget of only $7000, where the showcase was writer/director/star/editor/composer Shane Caruth’s intricate plotting. The whole intention with my re-watches is to give movies another chance and to honestly reflect upon why my feelings might have changed over time, for better or worse. That’s my intent, and while this day may have always been a matter of time for arriving, but I tried valiantly to watch Primer again and I quit. Yes, my apologies, but I tapped out.

I gave the movie twenty minutes before I came to the conclusion that I just wanted to do anything else with my time. I even tried watching a YouTube explanation video to give me a better summation, and even five minutes into that I came to the same conclusion that I wanted to do anything else with my fleeting sense of time. I think this is a case of accessibility and engagement.

Ultimately, this is the tale of two would-be inventors who keep reliving the same day to make money and win over a girl at a party. Reliving this day several times, with several iterations, and literally requiring a flowchart to keep it all together, is a lot of work for something that seemingly offers so little entertainment value beyond the academic pat on the back for being able to keep up with the inscrutable plotting. Look, I love time travel movies. I love the possibilities, the playfulness, the emphasis on ideas and casualty and imagination. I love the questions they raise and the dangers and, above all, the sheer fun. A time travel movie shouldn’t feel like you’re reading a book on arcane tax law. It needs to be, at the very least, interesting. Watching these two guys live out their lives, while on the peripheral more exciting things are happening with doubles, and we’re stuck with watching them migrate to this same party, or this same storage lockers and garages. It’s all so resoundingly low-stakes, even though betrayal and murder appear. I found this drama so powerfully uninteresting, and then structured and skewered and stacked to be an inscrutable, unknowable puzzle that makes you want to give up rather than engage. For me, there isn’t enough investment or intrigue to try and unpack this movie’s homework.

This is a lesson for me, as I have a newborn baby in my house, and sleep deprivation and fatigue are more a presence in my life, that I’m going to be more selective with what I choose to spend those moments of free time. Do I want to invest my time watching a movie I am not engaging with, that gives me so little to hold onto? When my friend Liz Dollard had her first child, she talked about not watching downer movies like 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, only having the emotional space for stories that wouldn’t be draining to her mental well-being. This meant low-stakes, uplifting, generally happy or familiar tales. I remember at the time thinking that she was willfully shuttling so many potential movies from her viewership, great films that could be challenging or depressing and deserving of being seen. Now, I completely get it, because after you’ve woken up several times during that night to feed a small child who has no means of communicating with you other than volcanic screaming, watching a long movie about human suffering can feel like a tall order. While Primer isn’t overwhelming as some kind of miserable dirge, it is too hard for me to access and gives me too little to hold onto.

This is a lesson for me, as I have a newborn baby in my house, and sleep deprivation and fatigue are more a presence in my life, that I’m going to be more selective with what I choose to spend those moments of free time. Do I want to invest my time watching a movie I am not engaging with, that gives me so little to hold onto? When my friend Liz Dollard had her first child, she talked about not watching downer movies like 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, only having the emotional space for stories that wouldn’t be draining to her mental well-being. This meant low-stakes, uplifting, generally happy or familiar tales. I remember at the time thinking that she was willfully shuttling so many potential movies from her viewership, great films that could be challenging or depressing and deserving of being seen. Now, I completely get it, because after you’ve woken up several times during that night to feed a small child who has no means of communicating with you other than volcanic screaming, watching a long movie about human suffering can feel like a tall order. While Primer isn’t overwhelming as some kind of miserable dirge, it is too hard for me to access and gives me too little to hold onto.

As a film critic for over twenty-five years of my life, I try my best to thoughtfully analyze every movie I sit down to write about, and I try to think about potential audiences and the artistic intentions for them, and whether choices help or hinder those intentions. Not every movie is going to be for me just like any other work of media; there are countless musical artists that I will never willfully listen to but have their respective fan bases. I know there are people that love Primer, as hard as it is for me to fathom. I know there are people out there that leap to the challenge of keeping the nine iterations and timelines together as time confusingly folds upon itself. I know there are sci-fi enthusiasts that respect and appreciate the stripped-down, more “realistic” application of time travel. I know there are people who celebrate this movie, but I am not one of them. Primer is simply not for me, and that’s okay. Not every work of art will be for every person. I doubt I’ll ever come back to Primer again for the rest of my life, but there’s so many more movies to watch every day, so why spend precious time on a movie you’re just not clicking with?

Adios, Primer. To someone else, you’re a wonderful movie. To me, you’re, as I wrote in 2004, a “techno lecture” disguised as an impenetrable film exercise.

Re-View Grade: Undetermined

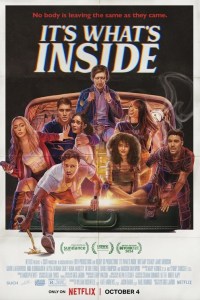

It’s What’s Inside (2024)

This sneaky little movie is exactly what I’ve been asking for from low-budget genre cinema, where creative ingenuity and imagination are the dominant forces to offset budget limitations. It’s What’s Inside is ostensibly a body swap movie between a group of friends stuck in a mansion overnight. A device allows eight people to swap into other hosts, and it plays as a silly party game early, before writer/director Greg Jardin increases the stakes. People pretend to be someone else and then explore that freedom, which usually means having affairs and getting a little too comfortable in other people’s bodies. Then there are… complications, and watching the characters frantically debate their new challenges and limitations with growing mistrust, exasperation, and betrayal makes for a delicious 90 minutes of surprises. Because there are multiple rounds of body-swapping, and eight starting characters, Jardin takes particular points to better clarify identities, from characters wearing Polaroids to a red-tinted sort of x-ray showing the real characters underneath the confusing physical surface. All of it helps, though I still had to ask who was really who quite often. I think watching it a second time would make it more coherent but also give me even more appreciation for Jardin’s slippery, shifting screenwriting. Here is a movie with rampant intrigue and imagination to spare, that maximizes its creativity to tap the body swap as an illuminating and destructive device to explore secret insecurities, desires, jealousies, and dissatisfaction in a friends group. It’s a wild trip, elevated by energetic and helpful editing, where the ideas are the main feature. It might not be much more than a bad overnight stay with bad people but It’s What’s Inside is top-notch genre filmmaking. It’s what’s inside the movie that matters most, its big imagination and fulfilling execution. Greg Jardin, you have my full attention with whatever movies you want to make from here on out.

This sneaky little movie is exactly what I’ve been asking for from low-budget genre cinema, where creative ingenuity and imagination are the dominant forces to offset budget limitations. It’s What’s Inside is ostensibly a body swap movie between a group of friends stuck in a mansion overnight. A device allows eight people to swap into other hosts, and it plays as a silly party game early, before writer/director Greg Jardin increases the stakes. People pretend to be someone else and then explore that freedom, which usually means having affairs and getting a little too comfortable in other people’s bodies. Then there are… complications, and watching the characters frantically debate their new challenges and limitations with growing mistrust, exasperation, and betrayal makes for a delicious 90 minutes of surprises. Because there are multiple rounds of body-swapping, and eight starting characters, Jardin takes particular points to better clarify identities, from characters wearing Polaroids to a red-tinted sort of x-ray showing the real characters underneath the confusing physical surface. All of it helps, though I still had to ask who was really who quite often. I think watching it a second time would make it more coherent but also give me even more appreciation for Jardin’s slippery, shifting screenwriting. Here is a movie with rampant intrigue and imagination to spare, that maximizes its creativity to tap the body swap as an illuminating and destructive device to explore secret insecurities, desires, jealousies, and dissatisfaction in a friends group. It’s a wild trip, elevated by energetic and helpful editing, where the ideas are the main feature. It might not be much more than a bad overnight stay with bad people but It’s What’s Inside is top-notch genre filmmaking. It’s what’s inside the movie that matters most, its big imagination and fulfilling execution. Greg Jardin, you have my full attention with whatever movies you want to make from here on out.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Challengers (2024)

The sweaty, sexy indie hit from the spring is about a tennis throuple told over the course of one pivotal match, where our two male athletes are at very different points in their careers and the woman who came between them. Patrick (Josh O’Conner) and Art (Mike Faist) are the best of friends when they started on the tennis circuit with dreams of making the big tournaments. They both set their sights on Tashi (Zendaya), a tennis phenom since her teenage years who is starting to reach her prime. The movie bounces back and forward through time (like a tennis ball!) to chart the changing relationships between the three, as we’re left to pick up the pieces as to what happened, who fell for who, who broke up with who, and how it relates to the central battle of wills playing out in the present-day match. The best part of Challengers are its characters and ever-shifting power dynamics, which makes each scene rich to digest and examine, especially once Tashi’s career takes an unexpected turn. Director Luca Guadagnino (Bones and All, Call Me By Your Name) keeps things lively with plenty of style including exercising every POV imaginable from the floor, to a tennis balls, and the players with racket banging in hand. We might have gotten a POV from a passing bird had it only gone longer. The movie is electrified by a pulse-pounding score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, a propulsive energy that reminded me of the similar service of the Run Lola Run soundtrack. What holds back the film for me is that the last act is dragged out and it culminates in an ending that is the most obvious as well as underwhelming, which makes the extended dragging even more ultimately tedious. The acting is good all around with each member getting to experience a high-point and low-point of their career and personal lives. However, it’s really Art and Tashi’s movie as Patrick serves as an elevated supporting role. And for a movie with such heat and hype, I guess I was expecting a little more action, if you will. Challengers is an intriguing, entertaining, and refreshingly adult sports drama that I wish had, forgive me, some more balls.

The sweaty, sexy indie hit from the spring is about a tennis throuple told over the course of one pivotal match, where our two male athletes are at very different points in their careers and the woman who came between them. Patrick (Josh O’Conner) and Art (Mike Faist) are the best of friends when they started on the tennis circuit with dreams of making the big tournaments. They both set their sights on Tashi (Zendaya), a tennis phenom since her teenage years who is starting to reach her prime. The movie bounces back and forward through time (like a tennis ball!) to chart the changing relationships between the three, as we’re left to pick up the pieces as to what happened, who fell for who, who broke up with who, and how it relates to the central battle of wills playing out in the present-day match. The best part of Challengers are its characters and ever-shifting power dynamics, which makes each scene rich to digest and examine, especially once Tashi’s career takes an unexpected turn. Director Luca Guadagnino (Bones and All, Call Me By Your Name) keeps things lively with plenty of style including exercising every POV imaginable from the floor, to a tennis balls, and the players with racket banging in hand. We might have gotten a POV from a passing bird had it only gone longer. The movie is electrified by a pulse-pounding score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, a propulsive energy that reminded me of the similar service of the Run Lola Run soundtrack. What holds back the film for me is that the last act is dragged out and it culminates in an ending that is the most obvious as well as underwhelming, which makes the extended dragging even more ultimately tedious. The acting is good all around with each member getting to experience a high-point and low-point of their career and personal lives. However, it’s really Art and Tashi’s movie as Patrick serves as an elevated supporting role. And for a movie with such heat and hype, I guess I was expecting a little more action, if you will. Challengers is an intriguing, entertaining, and refreshingly adult sports drama that I wish had, forgive me, some more balls.

Nate’s Grade: B

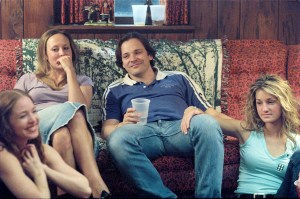

Garden State (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

Andrew Large Largeman (Braff) is an out-of-work actor living in an anti-depressant haze in LA. He heads back to his old stomping grounds in New Jersey when he learns that his mother has recently died. Andrew has to reface his psychiatrist father (Ian Holm), the source of his guilt and prescribed numbness. He has forgotten his lithium for his trip, and the consequences allow Andrew to begin to awaken as a human being once more. He meets old friends, including Mark (Peter Sarsgaard), who now digs graves for a living and robs them when he can. He parties at the mansion of a friend made rich by the invention of silent Velcro. Things really get moving when Andrew meets Sam (Natalie Portman), a free spirit who has trouble telling the truth and staying still. Their budding relationship coalesces with Andrews re-connection to friends, family, and the joys life can offer.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff deserves a medal for finally coaxing out the actress in Portman. She herself has looked like an overly medicated, numb being in several of her recent films (Star Wars prequels, I’m looking in your direction), but with her plucky, whimsical role in Garden State, Portman proves that her careers acting apex wasn’t in 1994’s The Professional when she was 12. Her winsome performance gives Garden State its spark, and the sincere romance between Sam and Andrew gives it its heart.

Sarsgaard is fast becoming one of the best young character actors out there. After solid efforts in Boys Don’t Cry and Shattered Glass, he shines as a coarse but affectionate grave robber that serves as Andrew’s motivational elbow-in-the-ribs. Only the great Holm seems to disappoint with a rare stilted and vacant performance. This can be mostly blamed on Braff’s underdevelopment of the father role. Even Method Man pops up in a very amusing cameo.

The humor in Garden State truly blossoms. There are several outrageous moments and wonderfully peculiar characters, but their interaction and friction are what provide the biggest laughs. So while Braff may shoehorn in a frisky seeing-eye canine, a knight of the breakfast table, and a keeper of an ark, the audience gets its real chuckles from the characters and not the bizarre scenarios. Garden State has several wonderfully hilarious moments, and its sharp sense of humor directly attributes to its high entertainment value. The film also has some insightful looks at family life, guilt, romance, human connection, and acceptance. Garden State can cut close like a surgeon but it’s the surprisingly elegant tenderness that will resonate most with a crowd.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Garden State is not a flawless first entry for Braff. It really is more a string of amusing anecdotes than an actual plot. The film’s aloof charm seems to be intended to cover over the cracks in its narrative. Braff’s film never ceases to be amusing, and it does have a warm likeability to it; nevertheless, it also loses some of its visual and emotional insights by the second half. Braff spends too much time on less essential moments, like the all-day trip by Mark that ends in a heavy-handed metaphor with an abyss. The emotional confrontation between father and son feels more like a baby step than a climax. Braff’s characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.

Garden State is a movie thats richly comic, sweetly post-adolescent, and defiantly different. Braff reveals himself to be a talent both behind the camera and in front of it, and possesses an every-man quality of humility, observation, and warmth that could soon shoot him to Hollywood’s A-list. His film will speak to many, and its message about experiencing lifes pleasures and pains, as long as you are experiencing life, is uplifting enough that you may leave the theater floating on air. Garden State is a breezy, heartwarming look at New York’s armpit and the spirited inhabitants that call it home. Braff delivers a blast of fresh air during the summer blahs.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

In the summer of 2024, there were two indie movies that defined the next years of your existence. If you were under 18, it was Napoleon Dynamite. If you were between 18 and 30, it was Garden State. Zack Braff’s debut as writer/director became a Millennial staple on DVD shelves, and I think at one time it might have been the law that everyone had to own the popular Grammy-winning soundtrack. It wasn’t just an indie hit, earning $35 million on a minimal budget of $2.5 million; it was a Real Big Deal, with big-hearted young people finding solace in its tale of self-discovery and shaking loose from jaded emotional malaise. If you had to determine a list of the most vital Millennial films, not necessarily on quality but on popularity and connection to the zeitgeist, then Garden State must be included. Twenty years later, it’s another artifact of its time, hard to fully square outside of that influential period. It’s a coming-of-age tale wrapped up in about every quirky indie trope of its era, including a chief example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, even though that term was first coined from the AV Club review of 2005’s Elizabethtown. Twenty years later, Garden State still has some warm fuzzies but loses its feels.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Natalie Portman had been an actress that I was more cool over until 2004 with the double-whammy of Garden State and her Oscar-nominated turn in Closer. She’s since become one of the most exciting actors who goes for broke in her performances whether they might work or not. In 2004, I thought her performance in Garden State was an awakening for her, and in 2024 it now feels so starkly pastiche. Bless her heart, but Portman is just calibrated for the wrong kind of movie. Her energy level is two to three times that of the rest of the movie, and while you can say she’s the spark plug of the film, the jolt meant to shake Andrew awake, her character comes across more as an overwritten cry for help. Sam is even more prototypical Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) than Kirsten Dunst’s bouncy character in Elizabethtown. Her entire existence is meant to provoke change upon our male character. This in itself is not an unreasonable fault; many characters in numerous stories are meant to represent a character’s emotional state. It’s just that there isn’t much to Sam besides a grab-bag of quirky characteristics: she’s a compulsive liar, though nothing is ever really done with this being a challenge to building lasting bonds; she’s incapable of keeping pets alive, and Andrew could be just another pet; she’s consumed with being unique to the point of having to stand up and blurt out nonsense words to convince herself that nobody in human history has duplicated her recent combination of sounds and body gestures, but she’s all archetype. She exists to push Andrew along on his reawakening, including introducing him and us to The Shins (“This song will change your life”). She’s entertaining, and Portman is charming, but it’s an example of trying so hard. I thought her cheeks must have hurt from holding a smile so long. I’m sure Braff would compare Sam to Annie Hall, as Diane Keaton was perhaps the mold for the MPDG, except she more than stood on her own and didn’t need a nebbish man to complete her.

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

Admittedly, that soundtrack is still a banger. It soars when it needs to, like Imogen Heep’s “Let Go” over the race-back-to-the-girl finale, and it’s deftly somber when it needs to, like Iron and Wine’s cover of “Such Great Heights” and “The Only Living Boy in New York” paired with our big movie kiss. It’s such a cohesive, thematic whole that lathers over the exposed seams of the movie’s scenic hodgepodge. Braff tried to find similar magic with his musical choices for 2006’s The Last Kiss, a movie he starred in but did not direct (he also provided un-credited rewrites to Paul Haggis’ adapted screenplay). That soundtrack is likewise packed with eclectic artists (he even snags Aimee Mann) but failed to resonate like Garden State. It’s probably because nobody saw the movie and Braff’s character was, as I described in my 2006 review, an overgrown man-child afraid his life lacks “surprises” now that he was going to be a father. Sheesh.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Re-View Grade: C+

In a Violent Nature (2024)

In a Violent Nature is going to be a very trying movie by design. Its entirety follows its very Jason-esque supernatural killer in near real-time as he goes through the woods and eventually kills several unlucky locals and partying teenagers. That means it’s several long sequences of watching the back of this hulking zombie killer walk through the woods and eventually get closer to victims. The actual kill scenes have some impressively nauseating gore, which might serve as a reward to the audience for enduring the lengthy walking. Seriously, this guy perambulates like a boss. He walks. And walks. And walks. Occasionally, he’ll kill someone in gruesome fashion, but most of his journey, and by extension the movie’s journey, is tagging along on his extensive nature hike. Is that going to be interesting to the average horror fan? Probably not. It’s designed to wear down your patience. The filmmakers clearly understand what effect their creative choices would have, and they went through with them anyway. It’s not like writer/director Chris Nash is lacking in style. His segment in 2014’s The ABCs of Death 2, “Z for Zygote,” is ingeniously horrifying. There is a great moment here where our killer’s hand is reaching toward the screaming face of his soon-to-be victim and then Nash performs a match cut with the same hand, now dripping with blood, reaching out for a desired necklace moments later. It’s quick and also subversive, denying the viewer our first opportunity at onscreen violence. This is a movie that works primarily in the realm of denying its target audience what it wants, and that is kind of fascinating to me. I don’t know if it’s enough to make me declare In a Violent Nature as good, but this movie seems destined to work on a different level than good/bad.

In a Violent Nature is going to be a very trying movie by design. Its entirety follows its very Jason-esque supernatural killer in near real-time as he goes through the woods and eventually kills several unlucky locals and partying teenagers. That means it’s several long sequences of watching the back of this hulking zombie killer walk through the woods and eventually get closer to victims. The actual kill scenes have some impressively nauseating gore, which might serve as a reward to the audience for enduring the lengthy walking. Seriously, this guy perambulates like a boss. He walks. And walks. And walks. Occasionally, he’ll kill someone in gruesome fashion, but most of his journey, and by extension the movie’s journey, is tagging along on his extensive nature hike. Is that going to be interesting to the average horror fan? Probably not. It’s designed to wear down your patience. The filmmakers clearly understand what effect their creative choices would have, and they went through with them anyway. It’s not like writer/director Chris Nash is lacking in style. His segment in 2014’s The ABCs of Death 2, “Z for Zygote,” is ingeniously horrifying. There is a great moment here where our killer’s hand is reaching toward the screaming face of his soon-to-be victim and then Nash performs a match cut with the same hand, now dripping with blood, reaching out for a desired necklace moments later. It’s quick and also subversive, denying the viewer our first opportunity at onscreen violence. This is a movie that works primarily in the realm of denying its target audience what it wants, and that is kind of fascinating to me. I don’t know if it’s enough to make me declare In a Violent Nature as good, but this movie seems destined to work on a different level than good/bad.

And yet, the movie invites a deeper contemplation through its very experimental nature. We’re walking side-by-side with this undead specter as he tromps through the woods looking to reclaim his special token, and it’s boring by design. I hate using that as an excuse because the movie does get rather tedious at parts, and yet it challenged me to engage more with the movie on an intellectual level, to examine its deliberate creative choices. Just about every slasher movie is designed around the clockwork killing of its easily disposable characters, usually dumb teenagers, by some powerful malevolent force. However, just about every slasher I can recall places the viewer in the perspective of the dumb teenagers engaging in dumb teenager antics, usually drinking and trying to engage in premarital sex. Let’s not pretend those characters are generally any more nuanced or well written than the villain stalking them. Instead of spending all our time with these character archetypes and the occasional pop-in from the villain, it’s reversed. It’s the dumb teenagers that pop-in while we’re on the journey with the slasher fiend. Does it make the kills hit harder because of the long stretches leading up to them because we see how many close calls there have been? Because this guy is trying his best? I don’t know, but the cries of In a Violent Nature being unbearably tedious makes me reflect on whether tedium is, by nature, part of the slasher genre, and perhaps we’ve all ignored the formula because of regular intervals of blood and boobs. Are dumb teenagers that much better company than a silent brute going for a walk?

And yet, the movie invites a deeper contemplation through its very experimental nature. We’re walking side-by-side with this undead specter as he tromps through the woods looking to reclaim his special token, and it’s boring by design. I hate using that as an excuse because the movie does get rather tedious at parts, and yet it challenged me to engage more with the movie on an intellectual level, to examine its deliberate creative choices. Just about every slasher movie is designed around the clockwork killing of its easily disposable characters, usually dumb teenagers, by some powerful malevolent force. However, just about every slasher I can recall places the viewer in the perspective of the dumb teenagers engaging in dumb teenager antics, usually drinking and trying to engage in premarital sex. Let’s not pretend those characters are generally any more nuanced or well written than the villain stalking them. Instead of spending all our time with these character archetypes and the occasional pop-in from the villain, it’s reversed. It’s the dumb teenagers that pop-in while we’re on the journey with the slasher fiend. Does it make the kills hit harder because of the long stretches leading up to them because we see how many close calls there have been? Because this guy is trying his best? I don’t know, but the cries of In a Violent Nature being unbearably tedious makes me reflect on whether tedium is, by nature, part of the slasher genre, and perhaps we’ve all ignored the formula because of regular intervals of blood and boobs. Are dumb teenagers that much better company than a silent brute going for a walk?

It was around the halfway point where I began to question whether this approach was causing me to develop empathy for our supernatural killing machine. The back-story is tragic, being a young child tricked by kids he thought were his friends, only to plunge to his death from a water tower. Children can be cruel, and if this was one’s ever-lasting memory of human interaction, then I would understand coming back as a murderous revenant. He also didn’t ask to be brought back to life. The dumb teenagers stole his mother’s necklace and his goal is to simply reclaim it. Yes, he’ll kill plenty of people that had nothing to do with bringing him back, collateral damage from messing with forces that humans should never mess with. He’s just on the hunt for his dear departed mother’s keepsake. In essence, he is looking for the item to return back to the land of the dead, to end being pulled back into corporeal existence. When you look at that context, every dead teenager becomes one step closer to finding that necklace and going back to his eternal slumber. Perhaps our big bad is suffering and looking for that pain to cease. When you’re quite literally walking beside this figure for the duration of the movie, it sparks a personal reflection whether you may be unexpectedly developing empathy. Is it simply projection and all proximal, spending all this time with only one character? Is this a human byproduct of wanting to imbue emotional depth to characters for our sense of engagement? I cannot say. When you walk a mile, or more accurately several, in another (dead) man’s shoes, maybe you start to see the world in his weary, irritable perspective and want that big nap back.

I have no idea how each viewer will respond to In a Violent Nature. I was wrestling with different mixed feelings, including boredom. I don’t think traditional fans of traditional horror will find the long slog worth taking its time to smell the proverbial flowers. I imagine most will grow restless, antsy, and maybe even angry, and that response is entirely valid and understandable. The novelty of watching the killer stalk his future victims in real time can be one of those ideas that, upon execution, feels better as a short film than as a feature experiment. I admire the gusto of embracing this approach and flipping the slasher script into what amounts to an unorthodox nature documentary between predator and prey. It’s an interesting approach that invites ongoing textual analysis with the genre, the depiction of the characters and their tired archetypes, as well as what makes these movies worth our time and passing investment. Likely there will be more people that shrug and deem In a Violent Nature a dull bore, but I’m also positive there will be people who find themselves unexpectedly thinking and feeling things they didn’t anticipate. Ultimately, it’s a movie I can begrudgingly admire more than engage with, but I appreciate taking the familiar and presenting it in a way we’ve seldom witnessed before.

I have no idea how each viewer will respond to In a Violent Nature. I was wrestling with different mixed feelings, including boredom. I don’t think traditional fans of traditional horror will find the long slog worth taking its time to smell the proverbial flowers. I imagine most will grow restless, antsy, and maybe even angry, and that response is entirely valid and understandable. The novelty of watching the killer stalk his future victims in real time can be one of those ideas that, upon execution, feels better as a short film than as a feature experiment. I admire the gusto of embracing this approach and flipping the slasher script into what amounts to an unorthodox nature documentary between predator and prey. It’s an interesting approach that invites ongoing textual analysis with the genre, the depiction of the characters and their tired archetypes, as well as what makes these movies worth our time and passing investment. Likely there will be more people that shrug and deem In a Violent Nature a dull bore, but I’m also positive there will be people who find themselves unexpectedly thinking and feeling things they didn’t anticipate. Ultimately, it’s a movie I can begrudgingly admire more than engage with, but I appreciate taking the familiar and presenting it in a way we’ve seldom witnessed before.

Nate’s Grade: C+

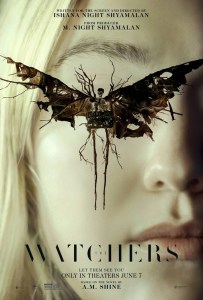

I Saw the TV Glow (2024)/ The Watchers (2024)

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

Nate’s Grade: B

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

Nate’s Grade: C

Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey 2 (2024)

The first Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey was, unquestionably, my worst film of 2023. It wasn’t merely a bad horror movie, it was a depressingly cynical cash-grab with such little forethought of how to subvert the wholesome legacy of its classic characters. As I said in my review: “The startling lack of imagination of everything else is depressing, as is the fact that this movie has earned over four million at the global box-office, hoodwinking enough rubberneckers looking for a good bad time. The problem is that Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey is only a bad bad time.” Oh, dear reader, I wasn’t looking forward to the inevitable deluge of follow-ups, as writer/director Rhys Frake-Waterfield would resupply his surprising success with further sinister revisions to public domain properties. He’s planning on a “Poohniverse” crossover event with a combination of Pooh, evil Pinnochio, vengeance-fuelled Bambi, and a traumatized or villainous Peter Pan. Again, schlocky movies that lean into their schlock can be wonderful things, but a movie that does next to nothing with its subversive hook, with the history of its cutesy iconography, and could be easily replaced with any other menacing slasher killer is beyond lazy, it’s insulting. I figured there could be nowhere to go but up with a sequel, and while Blood and Honey 2 is an improvement in just about every way, it’s still not enough to qualify as a fun or ironic treat.

The first Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey was, unquestionably, my worst film of 2023. It wasn’t merely a bad horror movie, it was a depressingly cynical cash-grab with such little forethought of how to subvert the wholesome legacy of its classic characters. As I said in my review: “The startling lack of imagination of everything else is depressing, as is the fact that this movie has earned over four million at the global box-office, hoodwinking enough rubberneckers looking for a good bad time. The problem is that Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey is only a bad bad time.” Oh, dear reader, I wasn’t looking forward to the inevitable deluge of follow-ups, as writer/director Rhys Frake-Waterfield would resupply his surprising success with further sinister revisions to public domain properties. He’s planning on a “Poohniverse” crossover event with a combination of Pooh, evil Pinnochio, vengeance-fuelled Bambi, and a traumatized or villainous Peter Pan. Again, schlocky movies that lean into their schlock can be wonderful things, but a movie that does next to nothing with its subversive hook, with the history of its cutesy iconography, and could be easily replaced with any other menacing slasher killer is beyond lazy, it’s insulting. I figured there could be nowhere to go but up with a sequel, and while Blood and Honey 2 is an improvement in just about every way, it’s still not enough to qualify as a fun or ironic treat.

Wakefield and new co-writer Matt Leslie (Summer of 84) completely rework the mythology and history established in the first movie, which is now revealed to be the literal movie-within-a-movie of the account of the Massacre of the 100 Acre Wood where Pooh and Piglet slaughtered a troupe of bad-acting British coeds. In this prior film, it was established that Pooh and his buddies were angry with Christopher Robin (Scott Chambers, replacing Nikolai Leon) when he left for college. They felt abandoned and grew feral and monstrous, rejecting the ways of man (though still wearing the clothes of man and driving the cars of man). However, now in the sequel it’s revealed they were always feral and blood-thirsty and it was Christopher who incorrectly remembered them as cute and fluffy. This scene makes for the hilarious visual of a child waving innocently at a blood-strewn manimal lurking about. Also, Christopher had a young brother who was abducted by the creatures of the 100 Acre Wood and never seen again. Also also, there was a mad scientist who was creating human-animal hybrids from missing children, so the blood-thirsty animals might not be actual animals after all (can you see where this is going?). While the first Blood and Honey movie did nothing with the characters, this movie actively gives them a tragic history with some twists and turns, enough to lay a mythos. The use of hypnotherapy-induced flashbacks isn’t exactly smooth or subtle, but I’ll take it. At least this movie provides a distinguishing plot that makes some use of its particular elements. Don’t mistake me, dear reader, this is faint praise at best, but after enduring the creatively bankrupt first film, it’s like a desperately needed oasis. Ultimately, it might all just be a mirage but at least it’s something to those of us who suffered!

In the grand sequel tradition, bigger is better, and now instead of two ferocious beasts wreaking havoc, it’s four, with the addition of Owl (Marcus Massey) and Tigger (Lewis Santer). None of these monsters has a particular style or attitude that distinguishes them. I guess Tigger calls people “bitch” a lot and slashes people. There is one point where hapless cops are investigating a crime scene and say, “Let’s bounce,” and Tigger says from the luxury of the shadows, “Hey, that’s my line.” I figured they’d incorporate the signature Tigger bounce on his tail, but perhaps that was too expensive to perform or that bounce was more a byproduct of the Disney version of the character, still under copyright, and not the available A.A. Milne version. The animal costumes look better than the cheap Halloween masks of the original, though for my money Owl looks more like a turkey vulture wearing cray paper. I’m sure we’ll get Kanga in the inevitable third movie in 2025 where her zombie baby leaps out of her pouch to feed on brains. There is a snazzy addition late into the proceedings where Pooh is welding a fiery chainsaw. It makes little sense for the character but it’s cool, so it’s excusable in lapsed movie logic.

In the grand sequel tradition, bigger is better, and now instead of two ferocious beasts wreaking havoc, it’s four, with the addition of Owl (Marcus Massey) and Tigger (Lewis Santer). None of these monsters has a particular style or attitude that distinguishes them. I guess Tigger calls people “bitch” a lot and slashes people. There is one point where hapless cops are investigating a crime scene and say, “Let’s bounce,” and Tigger says from the luxury of the shadows, “Hey, that’s my line.” I figured they’d incorporate the signature Tigger bounce on his tail, but perhaps that was too expensive to perform or that bounce was more a byproduct of the Disney version of the character, still under copyright, and not the available A.A. Milne version. The animal costumes look better than the cheap Halloween masks of the original, though for my money Owl looks more like a turkey vulture wearing cray paper. I’m sure we’ll get Kanga in the inevitable third movie in 2025 where her zombie baby leaps out of her pouch to feed on brains. There is a snazzy addition late into the proceedings where Pooh is welding a fiery chainsaw. It makes little sense for the character but it’s cool, so it’s excusable in lapsed movie logic.

I was hoping for more unique kills, twisted takes related to the characters, like Pooh turning some poor soul’s head into a honeypot. The kills are just grizzly and extensive, favoring quantity over quality. There are plenty of decapitations, gougings, impalings, and other fraught and violent encounters, nearly all of them featuring squealing, terrified women. It’s always women that seem to get the worst in these movies, but of course this is a feature and not a bug of the genre back to its 80s heyday. It gets relentless but I suppose at least these girls aren’t having their tops mysteriously fall off while they’re being butchered. A third act rave set piece features maybe two dozen kills and risks becoming tedious slaughter. It got to the point where I was hoping not to see another cowering person hiding behind a corner because it meant the sequence was going to be even more unbearably long (I’m not personally cut out for the Terrifiers).

In between the spillings of blood and guts is the attempts at human drama, namely Christopher Robin trying to live a normal life while also re-examining his past. Apparently people think he’s to blame for the massacre from the 100 Acre Wood, and so he’s become a pariah, whose very presence unsettles others. He’s trying to find steady work in a hospital setting but he’s blacklisted from pursuing his career because of the negative attention his name generates. He even has a romance with a single mom so that when the Robin family is inevitably skewered we have other characters that can be personally threatened to provide meaningful stakes. The life of Christopher Robin and his discovery of repressed memories makes for a surprising story foundation for Blood and Honey 2, especially when the plot of its predecessor was mostly Christopher being held prisoner and the baddies casually roaming and killing coeds. I think Chambers is a better actor as well, and he’s posed to be the writer/director of Neverland Nightmares, which just began principal photography a month and a half ago as of this writing. Good luck, guy.

In between the spillings of blood and guts is the attempts at human drama, namely Christopher Robin trying to live a normal life while also re-examining his past. Apparently people think he’s to blame for the massacre from the 100 Acre Wood, and so he’s become a pariah, whose very presence unsettles others. He’s trying to find steady work in a hospital setting but he’s blacklisted from pursuing his career because of the negative attention his name generates. He even has a romance with a single mom so that when the Robin family is inevitably skewered we have other characters that can be personally threatened to provide meaningful stakes. The life of Christopher Robin and his discovery of repressed memories makes for a surprising story foundation for Blood and Honey 2, especially when the plot of its predecessor was mostly Christopher being held prisoner and the baddies casually roaming and killing coeds. I think Chambers is a better actor as well, and he’s posed to be the writer/director of Neverland Nightmares, which just began principal photography a month and a half ago as of this writing. Good luck, guy.

While the budget has increased tenfold, Blood and Honey 2 is still a scuzzy, sleazy slasher movie at heart. If you’re in the mood for a low-budget exploitation movie heavy with gore, there may be enough to qualify this sequel as moderately mediocre, which again is a marked improvement from what I declared the worst movie of 2023. I’ll credit the influence of co-writer Matt Leslie to try and put some standards in place for this runaway gravy train of IP allocation. What’s scariest of all is what Frake-Waterfield’s unexpected success has wrought, encouraging imitators to jump on his now proven novelty act. There’s a 2025 Steamboat Willie horror movie called Screamboat as Steamboat Willie has now entered the public domain (but not other versions of Mickey). Will it be any good? I sincerely doubt it. Will it make money from curious horror hounds looking for an ironic twist on a wholesome childhood fixture? Most assuredly. This is our present. This is our future, and it’s the legacy of Frake-Waterfield and his ilk that stumbled onto a lucrative novelty act. Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey 2 is just bad, and for that it’s an improvement.

Nate’s Grade: D+

Hit Man (2024)

Hit Man is a movie that is wonderfully hard to describe. The premise has an easy-to-grasp hook that promises fun and hijinks, but where it goes from there takes on as many transformations as its protagonist, Gary Johnson (Glen Powell). It transforms from a fun game of undercover conning with wigs and silly accents into an unexpected rom-com hinging upon mistaken identity, maintaining assumed appearances, and secrets that then transforms into full film noir without losing its unique identity and the stakes of the character relationships. If you’d expect any filmmaker to pull off that trick, writer/director Richard Linklater has to be one of the best to keep things running smoothly, and that he does, as Hit Man is a crowd-pleasing comedy with some unexpected directions to keep everyone guessing until it lands on its own morally gray terms.