Blog Archives

Late Night with the Devil (2024)/ Immaculate (2024)

Late Nigh with the Devil is an intriguing novelty, a found footage item of 1970s late night talk show fame reportedly documenting the last show of Night Owls, a talk show hosted by a man who recently lost his wife to cancer and is also slipping in the ratings and losing his traction in the industry. So Jack Delroy (David Dastmalchian, best known as Polka Dot Man in 2021’s The Suicide Squad) gets the great idea to hold an exorcism live on stage or his big spooky Halloween show. What could go wrong, right? The movie is dedicated to upholding the style and awkward tone of 1970s talk show, and its commitment is by far its most interesting aspect to the found footage sub-genre. I wouldn’t classify the movie as necessarily scary, but it held my attention and I appreciated the corny little nuances of recreating an older form of television and comedy schtick, with a growing sense of foreboding as things start to get progressively worse and Jack pressures his new girlfriend, an occult writer, to bring out her possessed pupil. It takes a little long to get going, and the overall conspiracy of Jack’s connection to an Ilumminati-esque showbiz cult feels so tangential to be important, but I was objectively impressed with the overall recreation of an archaic form of TV. The conclusion, once all chaos is finally unleashed, breaks the rules of the found footage setup but at that point it’s welcomed and things can get a little more weird and visually audacious. Late Night with the Devil works more as a late-night curiosity than a boo-style horror thriller. I appreciated the committed efforts and artistry, as well as the game actors and some wicked gross-out makeup prosthetics, more than the overall movie.

Late Nigh with the Devil is an intriguing novelty, a found footage item of 1970s late night talk show fame reportedly documenting the last show of Night Owls, a talk show hosted by a man who recently lost his wife to cancer and is also slipping in the ratings and losing his traction in the industry. So Jack Delroy (David Dastmalchian, best known as Polka Dot Man in 2021’s The Suicide Squad) gets the great idea to hold an exorcism live on stage or his big spooky Halloween show. What could go wrong, right? The movie is dedicated to upholding the style and awkward tone of 1970s talk show, and its commitment is by far its most interesting aspect to the found footage sub-genre. I wouldn’t classify the movie as necessarily scary, but it held my attention and I appreciated the corny little nuances of recreating an older form of television and comedy schtick, with a growing sense of foreboding as things start to get progressively worse and Jack pressures his new girlfriend, an occult writer, to bring out her possessed pupil. It takes a little long to get going, and the overall conspiracy of Jack’s connection to an Ilumminati-esque showbiz cult feels so tangential to be important, but I was objectively impressed with the overall recreation of an archaic form of TV. The conclusion, once all chaos is finally unleashed, breaks the rules of the found footage setup but at that point it’s welcomed and things can get a little more weird and visually audacious. Late Night with the Devil works more as a late-night curiosity than a boo-style horror thriller. I appreciated the committed efforts and artistry, as well as the game actors and some wicked gross-out makeup prosthetics, more than the overall movie.

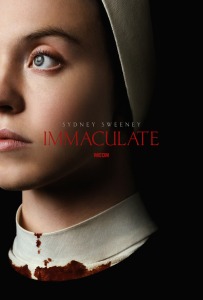

Nuns in Distress has long been a horror genre staple, as the mixture of Catholic imagery and overwrought religious themes proves an unbeatable mix with classic exploitation elements, the depraved and the sanctity. To this we have Immaculate with rising starlet Sydney Sweeney (HBO’s Euphoria) as an American nun traveling to a remote Italian convent and becoming an unwitting victim in a sinister ploy to gestate a new potential messiah. While very serious and broody in presentation, Immaculate is a pretty by-the-numbers mystery that goes to its most obvious route and becomes an overextended hostage thriller for Sweeney. The movie is at its best when it gets crazy, and that includes Sweeney, when she’s allowed to be all-out histrionic. For too long, the movie is too somber and simmering, which works best if the mystery is at least involving and surprising or we build to a great gonzo finish. I wish the movie was more wild. The ending is the best part of Immaculate, where Sweeney is pushed to the point of intense madness, while splattered in blood as per genre rules, and is forced to make extreme and personal choices. In that regard, perhaps Immaculate best operates on a metaphorical level about the horrors of pregnancy, more forced birth from oppressive leaders, and restricting women’s autonomy in a post-Roe v. Wade world. It’s a long wait to that worthwhile finale, and you might get restless from your unholy wait.

Nuns in Distress has long been a horror genre staple, as the mixture of Catholic imagery and overwrought religious themes proves an unbeatable mix with classic exploitation elements, the depraved and the sanctity. To this we have Immaculate with rising starlet Sydney Sweeney (HBO’s Euphoria) as an American nun traveling to a remote Italian convent and becoming an unwitting victim in a sinister ploy to gestate a new potential messiah. While very serious and broody in presentation, Immaculate is a pretty by-the-numbers mystery that goes to its most obvious route and becomes an overextended hostage thriller for Sweeney. The movie is at its best when it gets crazy, and that includes Sweeney, when she’s allowed to be all-out histrionic. For too long, the movie is too somber and simmering, which works best if the mystery is at least involving and surprising or we build to a great gonzo finish. I wish the movie was more wild. The ending is the best part of Immaculate, where Sweeney is pushed to the point of intense madness, while splattered in blood as per genre rules, and is forced to make extreme and personal choices. In that regard, perhaps Immaculate best operates on a metaphorical level about the horrors of pregnancy, more forced birth from oppressive leaders, and restricting women’s autonomy in a post-Roe v. Wade world. It’s a long wait to that worthwhile finale, and you might get restless from your unholy wait.

Nate’s Grades:

Late Night with the Devil: B-

Immaculate: C

Scoop (2024)

It’s like a British Bombshell, a behind-the-scenes account of the media attempting to hold key political and public figures to account for gross sexual imposition. With the Netflix drama Scoop, it just so happens to be Prince Andrew (Rufus Sewell), interviewed by BBC TV journalist Emily Maitlis (Gillian Anderson) in 2019 and scrutinized heavily for his close ties to former friend Jeffrey Epstein. The first half of the movie is about the wheeling and dealing behind the scenes to garner the high-profile interview, to convince Andrew he can clear his name after his connections to Epstein resurfaced. The second half of the movie is pretty much just the interview, which is indeed interesting to watch for the inherent drama, but after a while, I wondered what this movie was adding that I otherwise couldn’t gain from simply watching the actual 2019 BBC interview? There aren’t really scintillating details or clever scheming to guarantee the interview or outfox its news rivals, and the newsroom personalities, lead by Billie Piper (Doctor Who), are hard-working and tireless stock types that don’t leave much of a distinct impression even after the time together. It’s really a plainly presented dramatized version of the infamous interview, the one where Andrew was professing his innocence against his Epstein accuser with his bizarre argument that he has a condition where his body doesn’t sweat. Anderson is great, and Sewell is terrific as he melds into this figure of complacent arrogance and self-delusion (the makeup is also quite impressive). Still, if you’re really interested in gaining further insight, you might be better off looking elsewhere, or just watching the original interview. Consider this a bonus epilogue to Netflix’s The Crown for any die-hard royal aficionados.

It’s like a British Bombshell, a behind-the-scenes account of the media attempting to hold key political and public figures to account for gross sexual imposition. With the Netflix drama Scoop, it just so happens to be Prince Andrew (Rufus Sewell), interviewed by BBC TV journalist Emily Maitlis (Gillian Anderson) in 2019 and scrutinized heavily for his close ties to former friend Jeffrey Epstein. The first half of the movie is about the wheeling and dealing behind the scenes to garner the high-profile interview, to convince Andrew he can clear his name after his connections to Epstein resurfaced. The second half of the movie is pretty much just the interview, which is indeed interesting to watch for the inherent drama, but after a while, I wondered what this movie was adding that I otherwise couldn’t gain from simply watching the actual 2019 BBC interview? There aren’t really scintillating details or clever scheming to guarantee the interview or outfox its news rivals, and the newsroom personalities, lead by Billie Piper (Doctor Who), are hard-working and tireless stock types that don’t leave much of a distinct impression even after the time together. It’s really a plainly presented dramatized version of the infamous interview, the one where Andrew was professing his innocence against his Epstein accuser with his bizarre argument that he has a condition where his body doesn’t sweat. Anderson is great, and Sewell is terrific as he melds into this figure of complacent arrogance and self-delusion (the makeup is also quite impressive). Still, if you’re really interested in gaining further insight, you might be better off looking elsewhere, or just watching the original interview. Consider this a bonus epilogue to Netflix’s The Crown for any die-hard royal aficionados.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Love Lies Bleeding (2024)

With 2019’s Saint Maud, writer/director Rose Glass made her mark in the realm of religious horror, but it wasn’t just a high caliber boo-movie, it was an artistic statement on isolation, on obsession, and with stunning visuals to make the movie stand out even more. Next up, Glass has set her sights on a similar tale of isolation and obsession, in the realm of film noir.

With 2019’s Saint Maud, writer/director Rose Glass made her mark in the realm of religious horror, but it wasn’t just a high caliber boo-movie, it was an artistic statement on isolation, on obsession, and with stunning visuals to make the movie stand out even more. Next up, Glass has set her sights on a similar tale of isolation and obsession, in the realm of film noir.

In 1989, Lou (Kristen Stewart) works as the manager of a small gym in the American Southwest. She spots Jackie (Katy O’Brian) passing through on her way to a bodybuilding competition in Las Vegas. Together, the two women form a passionate relationship and are transfixed over one another, but in order to keep the good times rolling, each will be required to commit more desperate acts, including body removal and keeping secrets from Lou’s estranged father, Lou Senior (Ed Harris), a shooting range owner who operates as a cartel gun runner.

Love Lies Bleeding powers along like a runaway locomotive, a genre picture awash in the lurid and sundry language of film noir with a queer twist, until it goes completely off the rails by its conclusion, a pile-up of tones and ideas that’s practically admirable even if it doesn’t come together. Until that final act, what we’re given is a contemporary film noir escapade following desperate and obsessive people get completely well over their heads into danger. Reminiscent of the Wachowski’s Bound, we have a film noir that lets the ladies have all the fun playing into the tropes of the sultry femme fatales, and in this movie, both the lead characters are their own femme fatales and ingenues. Lou is the one who pushes steroid use onto Jackie, who resists at first and wants to go about building her body the old-fashioned way. Lou is also the one with the shady past and connections that come calling back at the worst time. Once fully hooked on her diet of steroids, Jackie becomes increasingly more unpredictable and desperate, leaving Lou to try and clean up their accumulating messes. They both use the other, they both enable the other, and they both project what they want onto the other even after their collective screw-ups. It’s a self-destructive partnership but neither can see through the haze of desire. They see one another as an escape, when really it’s an unraveling of self (though I suppose one could argue “living your best self,” already a subjective claim, could include being a genuine garbage human). In a way, this is a relationship that’s all rampant desire and unfulfilled consumption, and it leaves both parties always wanting more. It’s a bad romance with bad people doing bad things badly, and if that isn’t a tidy summation of most film noir, then I don’t know what is.

Love Lies Bleeding powers along like a runaway locomotive, a genre picture awash in the lurid and sundry language of film noir with a queer twist, until it goes completely off the rails by its conclusion, a pile-up of tones and ideas that’s practically admirable even if it doesn’t come together. Until that final act, what we’re given is a contemporary film noir escapade following desperate and obsessive people get completely well over their heads into danger. Reminiscent of the Wachowski’s Bound, we have a film noir that lets the ladies have all the fun playing into the tropes of the sultry femme fatales, and in this movie, both the lead characters are their own femme fatales and ingenues. Lou is the one who pushes steroid use onto Jackie, who resists at first and wants to go about building her body the old-fashioned way. Lou is also the one with the shady past and connections that come calling back at the worst time. Once fully hooked on her diet of steroids, Jackie becomes increasingly more unpredictable and desperate, leaving Lou to try and clean up their accumulating messes. They both use the other, they both enable the other, and they both project what they want onto the other even after their collective screw-ups. It’s a self-destructive partnership but neither can see through the haze of desire. They see one another as an escape, when really it’s an unraveling of self (though I suppose one could argue “living your best self,” already a subjective claim, could include being a genuine garbage human). In a way, this is a relationship that’s all rampant desire and unfulfilled consumption, and it leaves both parties always wanting more. It’s a bad romance with bad people doing bad things badly, and if that isn’t a tidy summation of most film noir, then I don’t know what is.

For the first hour, I was right onboard with the movie and its grimy atmosphere. The plot has a clear acceleration point, though the first twenty minutes is also given to some cheap “who-slept-with-who-before-they-knew-who” drama that I was instantly ready to put behind. However, once the climactic death hangs over our two lovers, there’s an immediate sense of danger that makes every scene evoke the gnawing desperation of our characters. The screenplay by Maud and Weronika Tofilska has such a deliberate cause-effect construction, and no film noir would be complete without the loose ends the characters would have to fret over. What also helps to elevate the immersion is the electric chemistry between Stewart (Spencer) and O’Brian (The Mandalorian), who worked previously in the world of women’s body building and clearly felt a kinship with this role, and she is also a born movie star. The two women are great together, enough so that the audience might start believing that these two lost souls are actually good for one another. We too might get seduced by the possibility that everything will turn out for the better, when we all know that’s not how film noir goes. I will say there are some gutsy decisions toward the end that will test audiences with their loyalty to our couple, but most felt completely in character even if their lingering impact is for you to reel back, hold your breath, and then heavily sigh.

It would also be impossible to discuss the movie without discussing just how overwhelmingly carnal it can be. I recently reviewed Drive-Away Dolls and noted how horny this lesbian sex comedy road trip was, though to me it felt empty and exploitative. With Love Lies Bleeding, the desire of these two women, and their mutual fulfillment, serves as another drug for them to mainline and then abuse. There is a hanger to the film’s gaze that is effective without feeling overly leering. The body building aspect puts a more natural fixation on lingering on the muscles and curves of human forms, and how Jackie is intending to transform herself into a fantasy version. The sexual content begins to ebb as soon as the murder content ramps up.

It would also be impossible to discuss the movie without discussing just how overwhelmingly carnal it can be. I recently reviewed Drive-Away Dolls and noted how horny this lesbian sex comedy road trip was, though to me it felt empty and exploitative. With Love Lies Bleeding, the desire of these two women, and their mutual fulfillment, serves as another drug for them to mainline and then abuse. There is a hanger to the film’s gaze that is effective without feeling overly leering. The body building aspect puts a more natural fixation on lingering on the muscles and curves of human forms, and how Jackie is intending to transform herself into a fantasy version. The sexual content begins to ebb as soon as the murder content ramps up.

Unfortunately, for a movie that gets by on some big artistic chances, not all of them work, and most of the miscues hamper the final thirty minutes. In the final act, Jackie abandons Lou and goes off on her own to her Las Vegas bodybuilding competition, and at that point it’s like she’s in a completely different kind of movie. Hers is a movie about drug addiction and hitting a wall, as she has some very public freakouts and hallucinations. Although from there, Love Lies Bleeding indulges in some peculiar imagery that emphasizes the extreme bulging muscles of Jackie like she was the Hulk. While the movie never presents these flights of fancy as magic realism meant to be taken literally, the sheer goofiness of these moments and imagery can hamper moments, especially during a climactic showdown that feels more like someone’s kinky dream. Ultimately, I don’t think the characters of Lou or Jackie are that interesting. Lou’s criminal past was deserving of more attention far earlier, and Jackie is so narrowly-focused that every scene with her after a certain point is only going to reinforce the same obsessive drive and perspective. Like other genres, film noir works with archetypes, and Love Lies Bleeding isn’t re-inventing the genre, merely giving it a very specific sapphic spin, set amidst the haze of the go-go 1980s.

Rose Glass is a hell of an intriguing filmmaker after two very different movies in two very different genres, both of which have been defined for decades by male filmmakers. This woman is a natural filmmaker with clear vision, and even through the bumps, you know you’re in good hands here with a storyteller that’s going to take you places. The cinematography is fluid and grimy to the point where you may feel the need to take a shower afterwards. Everything seems coated with dirt and sweat. The synth-heavy musical score accommodates rather than overwhelms. The performances are strong throughout, and the screenplay choices, while not always working out, are bold and in-character. Love Lies Bleeding provides just about everything you could want from a lesbian bodybuilder film noir thriller, a movie that recognizes the sizzle of its genre elements and makes grand, scuzzy use. At this point, we should all be paying attention to whatever Glass wants to do next as a filmmaker. It might not be perfect, it might not even work, but it will certainly demand our attention and time.

Nate’s Grade: B

Jersey Girl (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released March 25, 2004:

Writer/director Kevin Smith (Dogma) takes a stab at family friendly territory with the story of Ollie Trinke (Ben Affleck), a music publicist who must give up the glamour of the big city to realize the realities of single fatherhood. Despite brief J. Lo involvement, Jersey Girl is by no means Gigli 2: Electric Boogaloo. Alternating between edgy humor and sweet family melodrama, Smith shows a growing sense of maturity. Liv Tyler stars as Maya, a liberated video store clerk and Ollie’’s real love interest. Tyler and Affleck have terrific chemistry and their scenes together are a playful highlight. The real star of Jersey Girl is nine-year-old Raquel Castro, who plays Ollie’’s daughter. Castro is delightful and her cherubic smile can light up the screen. Smith deals heavily with familiar clichés (how many films recently end with some parent rushing to their child’’s theatrical production?), but at least they seem to be clichés and elements that Smith feels are worth something. Much cute kiddie stuff can be expected, but the strength of Jersey Girl is the earnest appeal of the characters. Some sequences are laugh-out-loud funny (like Affleck discovering his daughter and a neighbor boy engaging in “the time-honored game of “doctor””), but there are just as many small character beats that could have you feeling some emotion. A late exchange between Ollie and his father (George Carlin) is heartwarming, as is the final image of the movie, a father and daughter embracing and swaying to music. Jersey Girl proves to be a sweetly enjoyable date movie from one of the most unlikely sources.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

When I started putting together my list of 2004 movies to re-watch for this year’s slate, my wife was not pregnant. We had been trying for a year and experienced some heartbreaking setbacks, but now, as I write my review of Jersey Girl, my reality is that my wife is indeed pregnant, and we’re expecting a baby this October and very excited. As you can expect, I’m also nervous. Now this movie about the changes of fatherhood has significantly more meaning for me personally.

In 2004, I was but a 22-year-old soon-to-be college graduate but also a devotee of writer/director Kevin Smith since my teenage years of discovering movies in the oh-so-exciting go-go decade of 1990s independent film. This was supposed to be Smith’s career pivot, as he’d reportedly closed the book on his View Askew universe of crude comedies and stoner hi-jinks with 2001’s Jay and Silent Bob Strikes Back. Smith had become a parent in 1999 and, naturally, this altered the kinds of stories he wanted to tell. Although this didn’t last too long. In 2004, America was sick of Bennifer 1.0 and Jersey Girl was the second movie in less than a year pairing real-life couple Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez. The stink from 2003’s Gigli, and the tabloid overexposure, had tamped down the country’s demand for more Bennifer, so Miramax removed all publicity of Lopez from the movie, pushed the release date back half a year, and even publicly revealed that Lopez’s character dies in childbirth in the first ten minutes. Even with its relatively modest budget for a studio film, Jersey Girl under-performed, critics lambasted it, and Smith returned to his vulgar adult comedy playground with 2006’s Clerks II, the sequel to where it all began. With the occasional stop into horror, Smith has stayed in his own insular world and only gotten more insular with sequels to his early comedies for his ever-shrinking fandom.

More so than any other movie, Jersey Girl is the outlier, the oddity, the path not taken. Watching it again in 2024, I’m more forgiving of this outlier even if it proves harder to love. Much of this is likely my own relatability with the main character’s plight, a New York City workaholic publicist Ollie Trinkie (Affleck) who loses everything in a short window of time, namely his high-profile city job and his wife Gertrude (Lopez). Now he’s back living with his father Bart (George Carlin) in New Jersey and raising a little girl Gertie (Raquel Castro) on his own. It’s not a revolutionary film concept, a selfish adult takes on the responsibility of another and changes their perception of themself and the world. In a way, it likely happens to every new parent, or I would hope, a paradigm shift of perspective. The insights that Jersey Girl offers about parenthood and priorities are nothing new but that doesn’t mean they are bad or not worthwhile. Without the context of Smith’s tonal pivot, Jersey Girl would likely be forgotten, more than it already has been to history. It’s Smith’s spin on the family movie cliches we’ve seen before, and that means there’s a limit to how much further he can take the overly familiar.

More so than any other movie, Jersey Girl is the outlier, the oddity, the path not taken. Watching it again in 2024, I’m more forgiving of this outlier even if it proves harder to love. Much of this is likely my own relatability with the main character’s plight, a New York City workaholic publicist Ollie Trinkie (Affleck) who loses everything in a short window of time, namely his high-profile city job and his wife Gertrude (Lopez). Now he’s back living with his father Bart (George Carlin) in New Jersey and raising a little girl Gertie (Raquel Castro) on his own. It’s not a revolutionary film concept, a selfish adult takes on the responsibility of another and changes their perception of themself and the world. In a way, it likely happens to every new parent, or I would hope, a paradigm shift of perspective. The insights that Jersey Girl offers about parenthood and priorities are nothing new but that doesn’t mean they are bad or not worthwhile. Without the context of Smith’s tonal pivot, Jersey Girl would likely be forgotten, more than it already has been to history. It’s Smith’s spin on the family movie cliches we’ve seen before, and that means there’s a limit to how much further he can take the overly familiar.

It’s a little deflating to watch an artist known for his imagination and vocabulary utilizing the building blocks of maudlin family movies for his new story. Even with a different storyteller, they are still the same recognizable pieces seen before in hundreds of other feel-good movies about parents learning that children are more important than that big meeting or promotion. Of course reducing everything down in life is reductive, and maybe that big meeting could allow the parent to be more present for their kid, provide a better life being neglected, but whenever you set up the climactic choice between family and career, family always wins. Maybe David Wain (They Came Together) is the kind of subversive genre artist who could send up these age-old cliches and end with the workaholic parent choosing their selfish career. Regardless, the movie’s strengths are its sincerity rather than ironic detachment. It would be hard to make this kind of movie from a cynical smart-alecky approach, and Jersey Girl reveals what any View Askew fan has long known, that deep down at heart Smith is a big softie. It’s more apparent nowadays with Smith’s recent output of increasingly sentimental movies about relationships, as well as Smith’s copious social media posts showcasing his torrent of tears in response to a movie or TV show (as a man who frequently cries from movies and TV, this is no affront to me). Smith wanted to tell a personal story of his own life changes through the familiar family movie vehicle, and while it doesn’t entirely stretch beyond its copious influences, it’s still singing true to Smith’s sincerity.

This is far from the disaster many have made it out to be in the past twenty years. Lopez is really good in her brief opening appearance with a natural radiant charm that makes you mourn her absence just like Ollie. Liv Tyler (Armageddon reunion) shows up midway through as Maya, a sexually progressive video store clerk who becomes the next love interest for our widower. When she discovers, to Ollie’s embarrassment, that he hasn’t had sex for seven years, the entire time after his wife’s passing, she takes it upon herself to help the guy out with some charitable casual sex. The scene is funny and finally makes use of a setup Smith has taken time with prior, Gertie not flushing the toilet after use (something I can already regrettably relate to raising children). When his daughter comes home early, Ollie and Maya hide in the shower, and it appears they have gotten away with it, except Gertie finally remembers to flush the toilet, sending a burst of hot water that causes Maya to screech and reveal their half-naked tryst. From there, little Gertie sits them both down, reminiscent of what Ollie did with her and a friend when he caught them playing “doctor,” and she squares her gaze and intones, very maturely: “What are your intentions with my father?” Even the big climactic event, the children’s musical performance the parent can’t miss lest they break their child’s heart, gets a little edge when Gertie and her family perform the throat-slitting/pie-making number from Sweeney Todd. There’s a terrific exchange between Ollie and Will Smith all about the changing dynamic of fatherhood, what they do for their kids, and how rewarding it proves, and having Smith be your ace-in-the-hole is great.

This is far from the disaster many have made it out to be in the past twenty years. Lopez is really good in her brief opening appearance with a natural radiant charm that makes you mourn her absence just like Ollie. Liv Tyler (Armageddon reunion) shows up midway through as Maya, a sexually progressive video store clerk who becomes the next love interest for our widower. When she discovers, to Ollie’s embarrassment, that he hasn’t had sex for seven years, the entire time after his wife’s passing, she takes it upon herself to help the guy out with some charitable casual sex. The scene is funny and finally makes use of a setup Smith has taken time with prior, Gertie not flushing the toilet after use (something I can already regrettably relate to raising children). When his daughter comes home early, Ollie and Maya hide in the shower, and it appears they have gotten away with it, except Gertie finally remembers to flush the toilet, sending a burst of hot water that causes Maya to screech and reveal their half-naked tryst. From there, little Gertie sits them both down, reminiscent of what Ollie did with her and a friend when he caught them playing “doctor,” and she squares her gaze and intones, very maturely: “What are your intentions with my father?” Even the big climactic event, the children’s musical performance the parent can’t miss lest they break their child’s heart, gets a little edge when Gertie and her family perform the throat-slitting/pie-making number from Sweeney Todd. There’s a terrific exchange between Ollie and Will Smith all about the changing dynamic of fatherhood, what they do for their kids, and how rewarding it proves, and having Smith be your ace-in-the-hole is great.

It would be neglectful of me to forget the postscript that, nearly twenty years after the demise of their engagement, that Affleck and Lopez reunited and married in 2022. We’re in the current realm of Bennifer 2.0 (unless your version of Bennifer 2.0 was when he married Jennifer Garner, but I’ll let you decide if this era is 2.0 or 3.0) and Lopez has released a companion documentary to her 2024 visual album (a.k.a. collection of music videos) that features her relationship with Affleck, and it’s called The Greatest Love Story Never Told, and it’s gotten good reviews. Also of note, Castro grew up into a budding pop idol and appeared on The Voice and Empire.

There are things that work here, enough that Jersey Girl might honestly age better than the majority of Smith’s rude and crude comedies (see: re-reviews for Dogma and Strike Back, and Reboot). It will never garner the love of Smith’s more successful movies, but it doesn’t deserve any reputation as a forgotten stepchild among Smith’s oeuvre, especially when you consider the man also has Yoga Hosiers on that resume. In 2004, I referred to Jersey Girl as a “sweetly enjoyable date movie,” and this still stands twenty years later. I’m a little softer in several ways and more forgiving as an adult cinephile, and more welcome to genuine acts of sincerity, so the winning moments of the movie still hit their mark for me. I write this as my wife is still in her first trimester, and while the due date seems so far away I know it will rush by, and then I, like Ollie, will be juggling my life as I knew it with my life as I now know it (you better believe the scene where he loses his spouse in childbirth hit me harder as a new intrusive nightmare to occupy my mind). Jersey Girl isn’t anything new or special, but it was special for Smith, and he finds ways to make you understand what that means for him, and what it might mean for you. I’ll take that.

There are things that work here, enough that Jersey Girl might honestly age better than the majority of Smith’s rude and crude comedies (see: re-reviews for Dogma and Strike Back, and Reboot). It will never garner the love of Smith’s more successful movies, but it doesn’t deserve any reputation as a forgotten stepchild among Smith’s oeuvre, especially when you consider the man also has Yoga Hosiers on that resume. In 2004, I referred to Jersey Girl as a “sweetly enjoyable date movie,” and this still stands twenty years later. I’m a little softer in several ways and more forgiving as an adult cinephile, and more welcome to genuine acts of sincerity, so the winning moments of the movie still hit their mark for me. I write this as my wife is still in her first trimester, and while the due date seems so far away I know it will rush by, and then I, like Ollie, will be juggling my life as I knew it with my life as I now know it (you better believe the scene where he loses his spouse in childbirth hit me harder as a new intrusive nightmare to occupy my mind). Jersey Girl isn’t anything new or special, but it was special for Smith, and he finds ways to make you understand what that means for him, and what it might mean for you. I’ll take that.

Re-View Grade: B-

Damsel (2024)

After a decade of having a creative partner who literally has compiled over 4,000 pitches for possible movie and TV concepts, it was inevitable that Hollywood would eventually get close to some of them. This has happened before a few times, again given the significant library of my friend’s imagination, but never has it gotten as close as Damsel, Netflix’s new action fantasy film flipping the script of the shrinking violet being sacrificed to the clutches of a monster. In my friend’s pitch, the young girl is presented to a dragon with the implication that this regular offering will spare her small town from angry dragon fire. Just as she’s waiting to be eaten, the dragon undoes her bindings and they talk, because the dragon can talk, and he’s very curious why these people keep leaving him young girls every so many years. The revelation is that the dragon is not savage but intelligent, and the two bond, forming a partnership where she brings the dragon back to her community and shows them the error of their long-standing prejudices. Of course it all gets bigger from there, with warring kingdoms wanting to harness the last dragon to capture this unparalleled weapon of mass destruction. There was even a budding romance between the dragon and the young woman, with the possibility of the dragon turning into a human Beauty and the Beast-style. The title: Damsel. While my friend’s Damsel and Netflix’s Damsel have some core similarities, they do tell different stories built upon the same premise of the virgin sacrifice and the killer creature being more than what they seem.

After a decade of having a creative partner who literally has compiled over 4,000 pitches for possible movie and TV concepts, it was inevitable that Hollywood would eventually get close to some of them. This has happened before a few times, again given the significant library of my friend’s imagination, but never has it gotten as close as Damsel, Netflix’s new action fantasy film flipping the script of the shrinking violet being sacrificed to the clutches of a monster. In my friend’s pitch, the young girl is presented to a dragon with the implication that this regular offering will spare her small town from angry dragon fire. Just as she’s waiting to be eaten, the dragon undoes her bindings and they talk, because the dragon can talk, and he’s very curious why these people keep leaving him young girls every so many years. The revelation is that the dragon is not savage but intelligent, and the two bond, forming a partnership where she brings the dragon back to her community and shows them the error of their long-standing prejudices. Of course it all gets bigger from there, with warring kingdoms wanting to harness the last dragon to capture this unparalleled weapon of mass destruction. There was even a budding romance between the dragon and the young woman, with the possibility of the dragon turning into a human Beauty and the Beast-style. The title: Damsel. While my friend’s Damsel and Netflix’s Damsel have some core similarities, they do tell different stories built upon the same premise of the virgin sacrifice and the killer creature being more than what they seem.

Unfortunately, Netflix’s version is too narrow to be fully satisfying with its fairy tale script flip. We have Millie Bobby Brown as our titular damsel, Elodie, a woman trying to do well for her family, notably her father (Ray Winstone), stepmother (Angela Bassett), and younger sister. The young prince needs a bride, and the Queen (Robin Wright) isn’t too shy to still turn up her nose at her new in-laws that she sees as merely a means to an end, nothing more. Of course it’s revealed that this end is as “human sacrifice” to a dragon that has reportedly stalked the kingdom for centuries. Elodie is thrown down a vast canyon into the lair of an angry dragon (voiced by the unmistakable Shohreh Aghdashloo). From there, Elodie must use her wits to survive the dragon, escape above ground, and save her younger sister from being doomed to a similar fate.

The premise is so strong, upending ages-old tropes of the female sacrifice and the monstrous creature, as even with Netflix’s Damsel the dragon is a victim of historical slander. There’s so many places you can go with this, especially building upon the dynamic of the two of these discarded outcasts banding together to push back against the cruelty of society. However, that’s not the movie Netflix’s Damsel becomes. It sort of is, at the very end in resolution, with a latent promise of possible further adventures, but it’s mostly a locked-in survival thriller.

The premise is so strong, upending ages-old tropes of the female sacrifice and the monstrous creature, as even with Netflix’s Damsel the dragon is a victim of historical slander. There’s so many places you can go with this, especially building upon the dynamic of the two of these discarded outcasts banding together to push back against the cruelty of society. However, that’s not the movie Netflix’s Damsel becomes. It sort of is, at the very end in resolution, with a latent promise of possible further adventures, but it’s mostly a locked-in survival thriller.

I was not expecting the majority of Damsel to be Elodie’s basic survival once she’s been hurled into the pit by her recently dearly beloved (just following orders from mom, he says). It works, but it feels very constrained creatively. Now, I am generally a fan of these kinds of stories, the step-by-step survival tales where we are thinking alongside the plucky protagonist. I find them fun and follow a satisfying structure of amassing payoffs. It’s naturally enjoyable to watch a character tackle problems and succeed. However, it’s also vital that the audience understands the problem to know the challenge. In a fantasy setting, this requires more time to establish new rules and circumstances. Here we have a few sequences like when Elodie discovers bio-luminescent slugs and uses them as a light source for exploring her captivity (bonus: their sticky slime is healing). The timeline is relatively short, maybe a day at most, so it’s not like Elodie has to think about long-term survival; it’s much more immediate about escaping from the wrath of the predator. Just finding a safe hiding spot is enough. It’s engaging but by limiting the focus to an almost real-time survival cat-and-mouse game, it caps the movie’s creative possibility. I was far more interested in the prospect of eventually moving beyond the initial amity between Elodie and the dragon, where they could share their royal rage together. I kept waiting for this initial battle to give way into a different level of understanding, something to deepen and alter this relationship, but this doesn’t arrive until the very resolution of an hour after Elodie first hides from the fearsome dragon.

While I was never bored by watching Elodie think how to get over a crevasse, or how to navigate a treacherous pass, I was reminded of 2022’s The Princess, a spirited and gleefully violent feminist romp with a similar starting point of a damsel taking matters into her own hands and fighting for her freedom. With that film, the upturned premise was simple, but each new floor down the tower revealed something about our heroine, each new challenge was different and relied upon a different skill or tactic. Unfortunately, that movie was “deleted” from the Disney/Fox/Hulu library for tax purposes, though you can still rent or purchase it on Amazon but, as of now, no physical media exists. This is an excellent example of a movie with a limited scope that knows how to play to the limitations of story while still revealing character through action. While that movie lost some momentum and clarity when the princess was kicked out of her tower imprisonment, I found much to celebrate with the movie’s ingenuity and spirit. With Netflix’s Damsel, I was getting antsy to leave the cave and move things along. The twist about the true nature of the dragon, and her past with the legendary royal hero, should be obvious to most.

Let it be said that this is where Brown (Enola Holmes) graduated to being a steely and capable adult actress. She’s the star of the movie and has to command our attention and hold it for long stretches on her own. Brown throws herself into the physicality of the role with a relish that only makes her eventual triumph feel that much more worthy. The side characters don’t amount to much but have reliably winning actors to draw our attention. Aghdashloo (The Expanse) is a wonderful scene companion even with only a smoky voice. Wright (Wonder Woman) is haughty to the point of thin-lipped camp. Although this is a criminal under-utilization of the talents of Bassett (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever), who plays the concerned stepmother. That’s what happens when most of your movie is about one girl in a cave. The other characters are confined to the opening and closing of your survival thriller.

Let it be said that this is where Brown (Enola Holmes) graduated to being a steely and capable adult actress. She’s the star of the movie and has to command our attention and hold it for long stretches on her own. Brown throws herself into the physicality of the role with a relish that only makes her eventual triumph feel that much more worthy. The side characters don’t amount to much but have reliably winning actors to draw our attention. Aghdashloo (The Expanse) is a wonderful scene companion even with only a smoky voice. Wright (Wonder Woman) is haughty to the point of thin-lipped camp. Although this is a criminal under-utilization of the talents of Bassett (Black Panther: Wakanda Forever), who plays the concerned stepmother. That’s what happens when most of your movie is about one girl in a cave. The other characters are confined to the opening and closing of your survival thriller.

I suppose I’m being cheeky by referring to the movie as “Netflix’s Damsel” considering there isn’t any other version out there. I’m not accusing Netflix or screenwriter Dan Mazeau (Wrath of the Titans, Fast X) of ripping off my friend; it’s more an example of parallel thinking playing around with old fantasy tropes and giving them a new spin for modern times. I mostly enjoyed Netflix’s Damsel but couldn’t help but wonder what might have been, not just with my friend’s competing take on the material but with the story possibilities not taken here thanks to its limited scope. As a survival thriller in a fantasy setting, it works. There was just more that could have been, and while I should judge the movie that exists rather than the movie that could have been, Netflix’s Damsel is a fantasy action vehicle that swings its sword ably but had so much more potential to slay.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Oppenheimer (2023)

I finally did it. I watched all three hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one half of the biggest movie-going event of 2023, and arguably the most smarty-pants movie to ever gross a billion dollars. It was a critical darling all year long, sailed through its awards season, and racked up seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director for Nolan, a coronation for one of Hollywood’s biggest artists whose name alone is each new project’s biggest selling point. I’ve had friends falling over themselves with rapturous praise, and I’m sure you have too, dear reader, so the danger becomes raising your expectations to a level that no movie could ever meet. As I watched all 180 lugubrious minutes of this somber contemplation of man’s hubris, I kept thinking, “All right, this is good, but is it all-time-amazing good?” I can’t fully board the Oppenheimer hype train, and while I respect the movie and its exceptional artistry, I also question some of the key creative decision-making that made this movie exactly what it is, bladder-busting length and all.

I finally did it. I watched all three hours of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer, one half of the biggest movie-going event of 2023, and arguably the most smarty-pants movie to ever gross a billion dollars. It was a critical darling all year long, sailed through its awards season, and racked up seven Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director for Nolan, a coronation for one of Hollywood’s biggest artists whose name alone is each new project’s biggest selling point. I’ve had friends falling over themselves with rapturous praise, and I’m sure you have too, dear reader, so the danger becomes raising your expectations to a level that no movie could ever meet. As I watched all 180 lugubrious minutes of this somber contemplation of man’s hubris, I kept thinking, “All right, this is good, but is it all-time-amazing good?” I can’t fully board the Oppenheimer hype train, and while I respect the movie and its exceptional artistry, I also question some of the key creative decision-making that made this movie exactly what it is, bladder-busting length and all.

As per Nolan’s non-linear preferences, we’re bouncing back and forth between different timelines. The main story follows Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) as an upstart theoretical physicist creating his own academic foothold and then being courted to join the Manhattan Project to beat the Nazis in the formation of a nuclear bomb. The other timeline concerns the Senate approval hearing for Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), the former head of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) with a checkered history with Oppenheimer after the war. A third timeline, serving as a connecting point, involves Oppenheimer undergoing a closed-door questioning over the approval of his security clearance, which brings to light his life of choices and conundrums.

If I was going to be my most glib, I would characterize Oppenheimer in summary as, “Man creates bomb. Man is then sad.” There’s much more to it, obviously, and Nolan is at his most giddy when he’s diving into the heavy minutia of how the project came about, the many brilliant minds working in tandem, and sometimes in conflict, to usher in a new era of science and energy. Of course it also has radical implications for the world outside of academic theory. The world will never be the same because of Oppenheimer dramatically upgrading man’s self-destructive power. The accessible cautionary tale reminds me of a Patton Oswalt stand-up line: “We’re science: all about ‘coulda,’ no about ‘shoulda.’” Oh the folly of man and how it endures.

If I was going to be my most glib, I would characterize Oppenheimer in summary as, “Man creates bomb. Man is then sad.” There’s much more to it, obviously, and Nolan is at his most giddy when he’s diving into the heavy minutia of how the project came about, the many brilliant minds working in tandem, and sometimes in conflict, to usher in a new era of science and energy. Of course it also has radical implications for the world outside of academic theory. The world will never be the same because of Oppenheimer dramatically upgrading man’s self-destructive power. The accessible cautionary tale reminds me of a Patton Oswalt stand-up line: “We’re science: all about ‘coulda,’ no about ‘shoulda.’” Oh the folly of man and how it endures.

For the first two hours, the focus is the secretive Manhattan Project out in the New Mexico desert and its myriad logistical challenges, all with the urgency of being in a race with the Nazis who already have a head start (their break is Hitler’s antisemitism pushing out brilliant Jewish minds). That urgency to beat Hitler is a key motivator that allows many of the more hand-wringing members to absolve those pesky worries; Oppenheimer says their mission is to create the bomb and not to determine who or when it is used. That’s true, but it’s also convenient moral relativism, essentially saying America needs to do bad things so that the Germans don’t do worse things, a line of adversarial thinking that hasn’t gone away, only the name of the next competitor adjusts. This portion of the movie works because it adopts a similarly streamlined focus of smart people working together against a tight deadline. Looking at it as a problem needing to surmount allows for an engaging ensemble drama complete with satisfying steps toward solutions and breakthroughs. It makes you root for the all-star team and excitedly follow different elements relating to nuclear fusion and fission that you would have had no real bearing before Nolan’s intellectual epic. For those two galloping hours, the movie plays almost like a brainy heist team trying to pull together the ultimate job.

It’s the time afterwards where Oppenheimer expands upon the lasting consequences where the movie finds its real meaning as well as loses me as a viewer. The legacy of the bomb is one that modern audiences are going to be readily familiar with 80 years after the events that precipitated their arrival, and they haven’t exactly been shelved or become the world war deterrent hoped for. As one of Oppenheimer’s physicists says, a big bomb only works until someone creates a bigger bomb, and then the arms race starts all over again fighting for incremental supremacy when it comes to whether one’s military might could destroy the world ten times or twelve times over. When Oppenheimer begins having reservations of what he has brought into this world is when his character starts becoming more dynamic, but it’s also too late. He can’t undo what he’s done, the world isn’t going back to a safer existence before nuclear arms, so his tears and fears come as short shrift. There’s a scene where Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), castigates him and says, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then make all of us to feel sorry for you when there are consequences.” Now this is in reference to a different personal failing of our protagonist, but the message resonates; however, I don’t know if this is Nolan’s grand takeaway. The movie in scope and ambition wants to set up this man as a tragic figure that gave birth to our modern world, but like President Truman says, it’s not about who created the bomb but who uses it. Oppenheimer is treated like a harbinger of regret, but I don’t think the story has enough to merit this examination, which is why Oppenheimer peters out after the bomb’s immediate aftermath.

It’s the time afterwards where Oppenheimer expands upon the lasting consequences where the movie finds its real meaning as well as loses me as a viewer. The legacy of the bomb is one that modern audiences are going to be readily familiar with 80 years after the events that precipitated their arrival, and they haven’t exactly been shelved or become the world war deterrent hoped for. As one of Oppenheimer’s physicists says, a big bomb only works until someone creates a bigger bomb, and then the arms race starts all over again fighting for incremental supremacy when it comes to whether one’s military might could destroy the world ten times or twelve times over. When Oppenheimer begins having reservations of what he has brought into this world is when his character starts becoming more dynamic, but it’s also too late. He can’t undo what he’s done, the world isn’t going back to a safer existence before nuclear arms, so his tears and fears come as short shrift. There’s a scene where Oppenheimer’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), castigates him and says, “You don’t get to commit the sin and then make all of us to feel sorry for you when there are consequences.” Now this is in reference to a different personal failing of our protagonist, but the message resonates; however, I don’t know if this is Nolan’s grand takeaway. The movie in scope and ambition wants to set up this man as a tragic figure that gave birth to our modern world, but like President Truman says, it’s not about who created the bomb but who uses it. Oppenheimer is treated like a harbinger of regret, but I don’t think the story has enough to merit this examination, which is why Oppenheimer peters out after the bomb’s immediate aftermath.

It reminded me of an Oscar favorite from 2015, Adam McKay’s The Big Short, a true-ish account of real people profiting off the worldwide financial meltdown from 2008. It fools you into taking on the perspective of its main characters who present themselves as underdogs, keepers of a secret knowledge that they are trying to benefit from before an impending deadline. Likewise, the conclusion also makes you question whether you should have been rooting for this scheme all along since it was predicated on the economy crashing; these guys got their money but how many lives were irrevocably ruined to make their big score? With The Big Short, the movie-ness of its telling is part of McKay’s trickery, to ingratiate you in this clandestine financial world and to treat it like a heist or a con, and then to reckon whether you should have ever been rooting for such an adventure. Oppenheimer has a similar effect, lulling you with its admitted entertainment factor and beat-the-deadline structure. Once the mission is over, once the heroes have “won,” now the game doesn’t seem as fun or as justifiable. Except Oppenheimer could have achieved this effect with a judicious resolution rather than an entire third hour of movie shuffled throughout the other two like a mismatched deck of cards.

The last hour of the movie features a security clearance interrogation and a Senate confirmation hearing, neither of which have appealing stakes for an audience. After we watch the creation of a bomb, do we really care whether or not this one testy guy gets approved for a cabinet-level position or whether Oppenheimer might get his security clearance back? I understand that these stakes are meaningful for the characters, both essentially on trial for their lives and connections, but Nolan hasn’t made them as necessary for the audience. They’re really systems for exposition and re-examination, to play around with time like it was having a conversation with itself. It’s a neat effect when juggled smoothly, like when Past Oppenheimer is being interviewed by a steely and suspicious military intelligence office (Casey Affleck) while Future Oppenheimer laments to his project superior (Matt Damon) and then Even More Future Oppenheimer regrets his lack of candor to the review board. The shifty wheels-within-wheels nature of it all can be astounding when it’s all firing in alignment, but it can also feel like Nolan having a one-sided conversation with himself too often. It’s another reminder of the layers of narrative trickery and obfuscation that have become staples of a Christopher Nolan movie (I don’t think he could tell a knock-knock joke without making it at least nonlinear). The opposition to Oppenheimer is summarized by Strauss but I would argue the man didn’t need a public witch hunt to rectify what he’s done.

The last hour of the movie features a security clearance interrogation and a Senate confirmation hearing, neither of which have appealing stakes for an audience. After we watch the creation of a bomb, do we really care whether or not this one testy guy gets approved for a cabinet-level position or whether Oppenheimer might get his security clearance back? I understand that these stakes are meaningful for the characters, both essentially on trial for their lives and connections, but Nolan hasn’t made them as necessary for the audience. They’re really systems for exposition and re-examination, to play around with time like it was having a conversation with itself. It’s a neat effect when juggled smoothly, like when Past Oppenheimer is being interviewed by a steely and suspicious military intelligence office (Casey Affleck) while Future Oppenheimer laments to his project superior (Matt Damon) and then Even More Future Oppenheimer regrets his lack of candor to the review board. The shifty wheels-within-wheels nature of it all can be astounding when it’s all firing in alignment, but it can also feel like Nolan having a one-sided conversation with himself too often. It’s another reminder of the layers of narrative trickery and obfuscation that have become staples of a Christopher Nolan movie (I don’t think he could tell a knock-knock joke without making it at least nonlinear). The opposition to Oppenheimer is summarized by Strauss but I would argue the man didn’t need a public witch hunt to rectify what he’s done.

Lest I sound too harsh on Nolan’s latest, there are some virtuoso sequences that are spellbinding with technical artists working to their highest degree of artistry. The speech Oppenheimer gives to his Los Alamos colleagues is a horrifying lurch into a jingoistic pep rally, like he’s the big game coach trying to rally the team. The way the thundering stomps on the bleachers echo the rhythms of a locomotive in motion, driving forward at an alarming rate of acceleration, and then how Nolan drops the background sound so all we hear is Oppenheimer’s disoriented speech while the boisterous applause is muted, it’s all masterful to play with our sense of dread and remorse. This is who this man has become, and his good intentions of scientific discovery will be rendered into easily transmutable us-versus-them fear mongering politics. The ending imagery of Oppenheimer envisioning the world on fire is the exact right ending and hits with the full disquieting force of those three hours. The meeting with Harry Truman (Gary Oldman) is splendid for how undercutting it plays. Kitty’s interview at the hearing is the kind of counter-punching we’ve been waiting for and is an appreciated payoff for an otherwise underwritten character stuck in the Concerned Wife Back at Home role. The best parts are when Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves (Damon) are working in tandem to put together their team and location, as that’s when the movie feels like a well orchestrated buddy movie I didn’t know I wanted. The sterling cinematography, musical score, editing, all of the technical achievements, many of which won Oscars, are sumptuously glorious and immeasurably add to Nolan’s big screen vision.

I think I may understand why the subject of sex is something Nolan has conspicuously avoided before. Much has been made about the sex scenes and nudity in Oppenheimer, which seem to be the crux of Florence Pugh’s performance as Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s communist mistress through the years. The moment of Oppenheimer sitting during his hearing about his sexual tryst with an avowed communist leads to him imagining himself in the nude, exposed and vulnerable to these prying eyes and their judgment. Then Kitty imagines seeing Pugh atop her husband in his hearing seat, staring directly at her, and this sequence communicated both of their internal states well and felt justified. It’s the origin of the famous “I am become death” quote where the movie enters an unexpected level of cringe for a movie this serious. I was not prepared for this, so mild spoilers ahead if you care about such things, curious reader. We’re dropped into a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Jean where she takes a break to peruse his library shelves. She’s impressed that he has a Hindu text and pins it against her naked chest and slides atop Oppenheimer once again, requesting he read it to her rather than summarize it. “I am become death,” he utters, as he reads the Hindu Book of the Dead off Pugh’s breasts while they continue to have sex. Yikes. A big ball of yikes. If this is what’s in store, please go back to a sexless universe of men haunted by their lost women.

I think I may understand why the subject of sex is something Nolan has conspicuously avoided before. Much has been made about the sex scenes and nudity in Oppenheimer, which seem to be the crux of Florence Pugh’s performance as Jean Tatlock, Oppenheimer’s communist mistress through the years. The moment of Oppenheimer sitting during his hearing about his sexual tryst with an avowed communist leads to him imagining himself in the nude, exposed and vulnerable to these prying eyes and their judgment. Then Kitty imagines seeing Pugh atop her husband in his hearing seat, staring directly at her, and this sequence communicated both of their internal states well and felt justified. It’s the origin of the famous “I am become death” quote where the movie enters an unexpected level of cringe for a movie this serious. I was not prepared for this, so mild spoilers ahead if you care about such things, curious reader. We’re dropped into a sex scene between Oppenheimer and Jean where she takes a break to peruse his library shelves. She’s impressed that he has a Hindu text and pins it against her naked chest and slides atop Oppenheimer once again, requesting he read it to her rather than summarize it. “I am become death,” he utters, as he reads the Hindu Book of the Dead off Pugh’s breasts while they continue to have sex. Yikes. A big ball of yikes. If this is what’s in store, please go back to a sexless universe of men haunted by their lost women.

It’s easy to be swept away by all the ambition of Nolan’s Oppenheimer, a Great Man of History biopic that I think could have been better by being more judiciously critical of its subject. It’s a thoroughly well-acted movie where part of the fun is seeing known and lesser known name actors populate what would have been, like, Crew Member #8 roles for the sake of being part of this movie (Rami Malek as glorified clipboard-holder). Oppenheimer takes some wild swings, many of them paying off tremendously and also a few that made me scratch my head or reel back. It’s a demonstrably good movie with top-level craft, but I can’t quite shake my misgivings that enough of the movie could have been lost to history as well.

Nate’s Grade: B

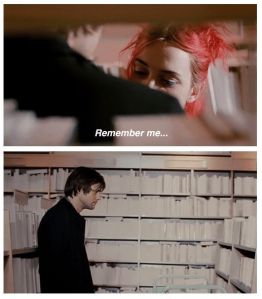

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released March 19, 2004:

No other movie this year captured the possibility of film like Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman’s enigmatic collaboration. Eternal Sunshine was a mind-bending philosophical excursion that also ended up being one of the most nakedly realistic romances of all time. Joel (Jim Carrey restrained) embarks on having his memories erased involving the painful breakup of Clementine (Kate Winslet, wonderful), an impulsive woman whose vibrant hair changes as much as her moods. As Joel revisits his memories, they fade and die. He starts to fall in love with her all over again and tries to have the process stop. This labyrinth of a movie gets so many details right, from the weird physics of dreams to the small, tender moments of love and relationships. I see something new and marvelous every time I watch Eternal Sunshine, and the fact that it’s caught on with audiences (it was nominated for Favorite Movie by the People’s friggin’ Choice Awards) reaffirms its insights into memory and love. I never would have thought we’d get the perfect romance for the new millennium from Kaufman. This is a beautiful, dizzingly complex, elegant romance caked in visual grandeur, and it will be just as special in 5 years as it will be in 50, that is if monkeys don’t evolve and take over by then (it will happen).

Nate’s Grade: A

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

“How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot:

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each prayer accepted, and each wish resigned;”

-Alexander Pope, Eloisa to Abelard (1717)

“Go ahead and break my heart, that’s fine

So unkind

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind

Oh, love is blind

Why am I missin’ you tonight?

Was it all a lie?”

-Kelly Clarkson, Mine (2023)

This one was always going to be special. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is not just one of my favorite movies, it’s one of those movies that occupies the place of Important Formative Art. It’s a movie that connected with me but it’s also one that profoundly affected me and changed me, that inspired me in my own creative ventures. With its elevated place in my memory, I’ll also admit that there was some mild trepidation about returning to it and having it not measure up to the impact it had all those twenty years ago. It’s impossible to recreate that first experience or to chase after it, but you hope that the art we consider great still has resonance over time. This happened before when I revisited 2000’s Requiem for a Dream, a movie that gobsmacked me in my youth, had such innate power and fascination, and had lessened over the decades. It was still good art but it wasn’t quite the same, and there’s a little tinge of disappointment that lingers.

When I saw the movie for the first time it was at a promotional screening. I was a senior in college and had dyed my hair bright red for the second time. After marveling over my first encounter with 1999’s Run Lola Run, I was determined to have hair like the titular Lola. My parents were hesitant and set parameters, like certain grade achievements, and I met them all. Afterwards they had nothing left to quibble so I dyed my hair red, as well as other colors, my sophomore year and then again my senior year. At the screening, a publicist for the studio asked if I wanted to compete for a prize. I demurred but then she came back and asked again, and sensing something to my advantage, I accepted. It turns out the pre-show contest was a Clementine (Kate Winslet) look alike contest and my only competition was a teen girl with one light swath of blue hair. The audience voted and I won in a landslide and was given a gift basket of official Eternal Sunshine merchandise that included the CD soundtrack and a bright orange hooded sweatshirt modeled after the one Clem wears in the movie. That sweatshirt quickly became one of my favorite items of clothing, something special that nobody else had from a movie I adored. I wore it everywhere and it became a comfort and a confidence builder. Back during my initial courtship with my wife, in the winter months of 2020, she held onto the orange hoodie as a memento to wear and think of me during our time apart. She said it even smelled like me, which was a comfort. It had meaning for us, and we cherished it. I had to marry her, of course, to ensure I’d eventually get the sweatshirt back in my possession (I kid).

The lessons of Eternal Sunshine run deep for me. On the surface it’s a breakup movie about an impulsive woman, Clem, deciding to erase her memories of her now ex-boyfriend Joel (Jim Carrey). Out of spite, he elects to have the same procedure, and from there we jump in and out of Joel’s head as a subconscious avatar experiences their relationship but in reverse. It’s the bad memories, the hurt and ache of a relationship nearing or past its end, but as each memory degrades and Joel goes further into the past, he discovers that there are actually plenty of enjoyable memories through those good times, the elation and discovery, the connections and development of love, that he doesn’t want to lose. He tries to fight against the procedure but it becomes a losing battle, and so he gets to ride shotgun in his cerebellum as this woman vanishes from his life. What began out of spite and heartache ends in mourning and self-reflection.

At its heart, the movie is asking us to reflect upon the importance of our personal experiences and how they shape us into the people that we are. This includes the ones that cause us pain and regret. The human experience is not one wholly given to happiness, unfortunately, but there are lessons to be had in the scars and pain of our individual pasts. I’m not saying that every point of discomfort or pain is worthwhile, as there are many victims who would say otherwise, but we are the sum total of our experiences, good and bad. With enough distance, wisdom can be gained, and perhaps those events that felt so raw and unending and terrible eventually put us on the path of becoming the person you are today. Now, of course, maybe you don’t like the person you are now, but that doesn’t mean you’re also a prisoner to your past and doomed to dwell in misery.

After my divorce from my previous wife in 2012, I wrote a sci-fi screenplay following some of the same themes from Eternal Sunshine. It was about two dueling time travelers trying to outsmart one another, one hired to ensure a romantic couple never got together and one hired to make sure that they had. The characters represented different viewpoints, one arguing that people are the total of their experiences and the other arguing people should be capable of choosing what experiences they want ultimately as formative. Naturally, through twists and turns, the one time traveler learns a lesson about “living in the now,” to stop literally living in the past and trying to correct other people’s perceived mistakes, and that our experiences, and our heartache, can be valuable in putting us into position to being the people we want or living the lives we seek. It shouldn’t be too hard to see that I was working through my own feelings with this creative venture. It got some attention within the industry and I dearly hope one day it can be made into a real movie. It’s one of my favorite stories I’ve ever written and I’m quite proud of it. It wouldn’t exist without Eternal Sunshine making its mark on me all those years ago.

It’s an amazing collaboration between director Michel Gondry and the brilliant mind of Charlie Kaufman. The whimsical, hardscrabble DIY-style of Gondry’s visuals masterfully keeps the viewer on our toes, as Joel’s memories begin vanishing and collapsing upon one another in visually inventive and memorable ways. There’s moments like Joel, after finding Clem once she’s erased her memory of him, and he storms off while row after row of lights shuts off, dooming this memory to the inky void. There’s one moment where he’s walking through a street and with every camera pan more details from the store exteriors vanish. A similar moment occurs through a store aisle where all the paperbacks become blank covers. It’s a consistent visual inventiveness to communicate the fraying memories and mind of Joel, which becomes its own playground that allows us to better understand him. The score by Jon Brion (Magnolia) is also a significant addition, constantly finding unique and chirpy sounds to provide a sense of earned melancholy. By experiencing their relationship backwards, it allows us to have a sense of discovery about the relationship. This is also aided by Kaufman’s sleight-of-hand structure, with the opening sequence misleadingly the beginning of their relationship when it’s actually their second first time meeting one another. The pointed details of relationships, both on the rise and decline, feel so achingly authentic, and the characters have more depth than they might appear on the surface. Joel is far more than a hopeless romantic. Clem is far more than some Manic Pixie Dream Girl, a term coined for 2005’s Elizabethtown. She tells Joel that she’s not some concept, she’s not here to complete his life and add excitement; she’s just a messed up girl looking for her own peace of mind and she doesn’t promise to be the answer for any wounded romantic soul.

The very end is such a unique combination of feelings. After Mary (Kirsten Dunst) discovers that she’s previously had her memories of an affair with her boss erased, she takes it upon herself to mail every client their files so that they too know the truth. Joel and Clem must suffer listening to their recorded interviews where they are viciously attacking one another, like Clem declaring Joel to be insufferably boring who puts her on edge, and Joel accuses her of using sex to get people to like her. Both are hurt by the accusations, both shake them off as being inaccurate, and yet it really is them saying these things, recorded proof about the ruination of their relationship. Would getting together be doomed to eventually repeat these same complaints? Clem walks off and Joel chases after her and tells her not to go. Teary-eyed, she warns that she’ll grow bored of him and resentful because that’s what she does, and she’ll become insufferable to him. And then Joel says, “Okay,” an acceptance that perhaps they may repeat their previous doomed path, maybe it’s inevitable, but maybe it also isn’t, and it’s worth it to try all the same. Maybe we’re not destined to repeat our same mistakes. Then it ends on a shot of our couple frolicing in the snow, the descending white beginning to blot out the screen, serving as a blank slate. It’s simultaneously a hopeful and pessimistic ending, a beautifully nuanced conclusion to a movie exploring the human condition.

Winslet received an Oscar nomination for her sprightly performance, and deservedly so, but it’s Carrey that really surprises. He had already begun to stretch his dramatic acting muscles before in the 1998 masterpiece The Truman Show and the far-from-masterpiece 2001 film The Majestic. He’s so restrained in this movie, perfectly capturing the awkwardness and passive aggressive irritability of the character, a man who views his life as too ordinary to be worth sharing. Clem begs him to share himself since she’s an open book but he’s more mercurial. She wants to get to know him better but to Joel there’s a question of whether or not he has anything worthwhile getting to know. Carrey sheds all his natural charisma to really bring this character to life. It’s one of his best performances because he’s truly devoted to playing a character, not aggressively obnoxious Method devotion like in 1999’s Man on the Moon.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a messy, enlightening, profound, playful, poignant, and mesmerizing movie. A perfect collaboration between artists with unique creative perspectives. I see something new every time I watch it, and it’s already changed my life in different ways. I used to see myself as Joel when I was younger, but then I grew to see him as self-pitying and someone who too often sets himself up for failure by being too guarded and insular. It’s a reminder that our cherished relationships remain that way by allowing ourselves to be vulnerable and open. We are all capable and deserving of love.

Re-View Grade: A

The Passion of the Christ (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released February 25, 2004:

The Passion of the Christ is a retelling of the last 12 hours of Jesus Christ’s life (perhaps you’ve heard of him?). In these final hours we witness his betrayal at the hands of Judas, his trial by Jewish leaders, his sentencing by Pontius Pilate, his subsequent whippings and torture and finally his crucifixion. Throughout the film Jesus is tempted by Satan, who is pictured as a pasty figure in a black hood (kind of resembling Jeremy Irons from The Time Machine if anyone can remember). The Passion spares no expense to stage the most authentic portrayal of what Jesus of Nazareth endured in his final 12 hours of life.

For all the hullabaloo about being the most controversial film in years (and forgive me for even using the term “hullabaloo”), I can’t help but feel a smidgen of disappointment about the final product. The Passion is aptly passionate and full of striking images, beautiful photography and production values, and stirring performances all set to a rousing score. But what makes The Passion disappointing to me is the characters. You see, Mel Gibson’s epic does not devote any time to fleshing out the central characters. They are merely ciphers and the audience is expected to plug their feelings and opinions into these walking, bleeding symbols to give them life. Now, you could argue this is what religion is all about, but as far as a movie’s story goes it is weak. The Passion turns into a well-meaning and slick spectacle where character is not an issue. And as a spectacle The Passion is first-rate; the production is amazing and the violence is graphic and gasp-inducing. Do I think the majority of people will leave the theater moved and satisfied? Yes I do. But I can’t stop this nagging concern that The Passion was devoid of character and tried covering it up with enough violence to possibly twist its message into a Sunday school snuff film.