Blog Archives

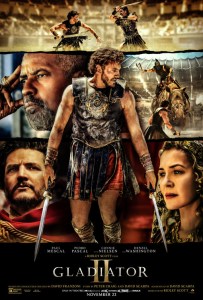

Gladiator II (2024)

It’s been twenty-four years since Russel Crowe, in his Oscar-winning role, bellowed, “Are you not entertained?” We were, we really were, and Gladiator was a huge hit in 2000 but has also held up as a twenty-first century classic that revived the sword-and-sandals epic. The late sequel hews quite closely to the path of the original Gladiator, a rare example of a movie that was quite literally writing the script as they went and succeeded wildly. The second go-round has a strong same-y feel, which is natural with sequels, but it also has trouble simply standing in the shadow of its superior predecessor.

It’s been twenty-four years since Russel Crowe, in his Oscar-winning role, bellowed, “Are you not entertained?” We were, we really were, and Gladiator was a huge hit in 2000 but has also held up as a twenty-first century classic that revived the sword-and-sandals epic. The late sequel hews quite closely to the path of the original Gladiator, a rare example of a movie that was quite literally writing the script as they went and succeeded wildly. The second go-round has a strong same-y feel, which is natural with sequels, but it also has trouble simply standing in the shadow of its superior predecessor.

This time we follow Paul Mescal (Aftersun) as a Roman expat who’s been living abroad as a simple man of the people, except when violence is called upon. His land is conquered by Rome, his beloved is killed, and he’s sold into slavery only to be selected to be trained as a gladiator and only to become a fan favorite who could possibly unseat the Emperor(s). Sounds familiar, right, plus with the revenge motivation? Mescal is playing Lucius, the adult nephew to the late emperor played by Joaquin Phoenix. He’s all grown up and with abs. This Maximum stand-in is actually the blandest character in the film, a scolding figure who says little and doesn’t want to be in any position of leadership. It makes for a lackluster hero especially compared to the presence and magnetism of Crowe in his leading man prime. Fortunately there’s entertaining side characters, notably Denzel Washington (The Equalizer) as a bisexual wheeler-dealer who manipulates his way to the top of the Roman Senate, even garnering the attention of the hedonist twin emperors. The script utilizes a lot of conveniences, from revelations of bloodlines to an adjacent crypt that just so happens to have old Maximus’ armor and sword. Washington’s schemes, more loose-goosey and the benefit of convenient luck than machiavellian plotting, provide the missing entertainment value from Mescal’s underdog-seeking-vengeance arc. Director Ridley Scott returns and stages some fun Colosseum action set pieces, including an aquatic based naval battle with literal sharks. The opening siege against a coastal city by the powerful Roman army is wonderfully visualized. I was never bored but I can’t say that the movie is operating at close to the same level. The second half kind of creaks to a close, with a final one-on-one that feels too lopsided and unfulfilling. The emotional resonance of the prior movie is sufficiently lacking. While Gladiator II can still get your blood moving, it’s also an exercise in rote blood-letting as diminished franchise returns.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Nobody (2021)

If you ever wanted to see Saul Goodman crack skulls like John Wick, well you’re in luck with Nobody, a perfectly enjoyable action movie that does little to separate itself from its influences. Bob Odenkirk has been on a wild ride of a career, beginning primarily as a writer and director of cult comedies and then turning into an award-nominated dramatic actor thanks to Breaking Bad and its spinoff, and now he gets his chance to try being an improbable action hero. Odenkirk plays a family man who freezes during a break-in. We think he’s a push-over, an office drone, a nobody, but he’s really nothing of the sort, and woe unto those who come after him for bloody vengeance. The plot is pretty thin and plays out very much like a combination of Joker and The Equalizer, even down to its final, explosive, booby trap-laden final act. Much like the John Wick series, the importance is heavily placed upon the action and stunt choreography. We’re here for the spectacle. While Nobody doesn’t rise to the dizzy action highs of the Wick franchise, it’s an above average action movie and has fun moments of unique style thanks to director Ilya Naishuller (Hardcore Henry). A fight scene aboard a bus is extensive and exhausting, leaving both parties gasping and bloody. Odenkirk’s character isn’t quite the impervious video game avatar that Keanu Reeves portrays; he’s rusty and limited, but by the time that climax comes rolling, he might as well be the Terminator. It’s not enough to disrupt the fun of the movie but the one area that could separate Nobody from the punchy pack just vanishes by the conclusion. The addition of Russian gangsters feels too cliche and unremarkable, as they just serve as a quick pipeline for bad guys to be abused. The addition of 83-year-old Christopher Lloyd as a sneakily formidable nursing home resident is much less cliche and much more enjoyable. If you’re looking for an action movie that packs a punch without taxing your brain, Nobody hits enough of the right buttons to suffice.

If you ever wanted to see Saul Goodman crack skulls like John Wick, well you’re in luck with Nobody, a perfectly enjoyable action movie that does little to separate itself from its influences. Bob Odenkirk has been on a wild ride of a career, beginning primarily as a writer and director of cult comedies and then turning into an award-nominated dramatic actor thanks to Breaking Bad and its spinoff, and now he gets his chance to try being an improbable action hero. Odenkirk plays a family man who freezes during a break-in. We think he’s a push-over, an office drone, a nobody, but he’s really nothing of the sort, and woe unto those who come after him for bloody vengeance. The plot is pretty thin and plays out very much like a combination of Joker and The Equalizer, even down to its final, explosive, booby trap-laden final act. Much like the John Wick series, the importance is heavily placed upon the action and stunt choreography. We’re here for the spectacle. While Nobody doesn’t rise to the dizzy action highs of the Wick franchise, it’s an above average action movie and has fun moments of unique style thanks to director Ilya Naishuller (Hardcore Henry). A fight scene aboard a bus is extensive and exhausting, leaving both parties gasping and bloody. Odenkirk’s character isn’t quite the impervious video game avatar that Keanu Reeves portrays; he’s rusty and limited, but by the time that climax comes rolling, he might as well be the Terminator. It’s not enough to disrupt the fun of the movie but the one area that could separate Nobody from the punchy pack just vanishes by the conclusion. The addition of Russian gangsters feels too cliche and unremarkable, as they just serve as a quick pipeline for bad guys to be abused. The addition of 83-year-old Christopher Lloyd as a sneakily formidable nursing home resident is much less cliche and much more enjoyable. If you’re looking for an action movie that packs a punch without taxing your brain, Nobody hits enough of the right buttons to suffice.

Nate’s Grade: B

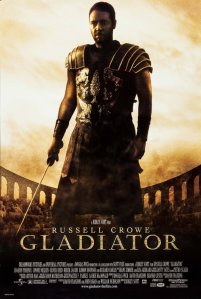

Gladiator (2000) [Review Re-View]

Originally released May 5, 2000:

Originally released May 5, 2000:

Director Ridley Scott has given the world of cinema some of its most unforgettable visual experiences. But can Scott breath new life into a genre whose heyday was when a badly dubbed Steve Reeves oiled his chest and wrestled loincloth-clad extras in the 1950s?

The year is roughly 180 AD and Rome is just finishing up its long-standing assault on anything that moves in the European continent. General Maximus (Russell Crowe) merely wants to retire back to his loving family and get away from the doom and war that has plagued his life. This is made all the more difficult when the ailing Emperor bypasses his treacherous son Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix) and decides to crown Maximus as the Defender of Rome. Because of this Commodus rises to power through bloody circumstances and has Maximus assigned to execution and his family crucified. You’d think crucifixion would be so passé by now. Maximus escapes only to be sold into slavery and bought by a dirt-run gladiator training school. As he advances up the chain and learns the tricks of the primal sport he seeks but vengeance for his fallen family.

Gladiator is an absorbing and sweeping spectacle of carnage and first-rate entertainment. The action is swift and ruthlessly visceral. The first movie in a long time to literally have me poised on the edge of my seat. The blood spills in the gallons and life and limb go flying enough your theater owner may consider setting down a tarp.

What Gladiator doesn’t sacrifice to the muscle of effects and action is storytelling. Are you listening George Lucas? Gladiator may unleash the beast when the rousing action is loose, but this is coupled with compelling drama and complex characters. Phoenix may at first seem like a snotty brat with an unhealthy eye for his sister (Connie Nielsen), but the further Gladiator continues the more you see in his eyes the troubled youth who just wants the love of his father that was never bestowed to him. Maximus is a devoted family man who regularly kisses clay statues of his family while away, and must ceremoniously dust himself with the earth before any battle.

What Gladiator doesn’t sacrifice to the muscle of effects and action is storytelling. Are you listening George Lucas? Gladiator may unleash the beast when the rousing action is loose, but this is coupled with compelling drama and complex characters. Phoenix may at first seem like a snotty brat with an unhealthy eye for his sister (Connie Nielsen), but the further Gladiator continues the more you see in his eyes the troubled youth who just wants the love of his father that was never bestowed to him. Maximus is a devoted family man who regularly kisses clay statues of his family while away, and must ceremoniously dust himself with the earth before any battle.

The acting matches every sword blow and chariot race toe-for-toe. Russell Crowe marks a first-rate staple of heroism. Every calculating glare he exhibits shows the compassion and ferocity of this warrior. He becomes a rare breed – an action hero who can think and actually act. Oliver Reed, in what sadly was his last role, turns in a splendid and charismatic turn as the head of the gladiator school of Fine Arts and Carnage. Mysteriously everyone carries a British accent closer to them then a toga two sizes too small. Even Crowe who is nicknamed “The Spaniard” speaks like he walked out of Masterpiece Theater.

The effects and visuals are a sumptuous feast. The aerial shots of Rome and the Coliseum are simply breath taking. Gladiator rivals American Beauty for the most rose petals used in a movie, except in this one they don’t shoot out of Mena Suvari’s breasts.

Ridley Scott’s track record may be hit or miss but Gladiator is definitely one sorely not to be missed.

Nate’s Grade: A-

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

As Russell Crowe famously barked, “Are you not entertained?’ It was hard to argue in 2000 and it still holds true to this day. Gladiator was a big-budget throwback to the swords-and-sandals epics of old Hollywood. It was a box-office hit, made Crowe a star, and won five Academy Awards including Best Picture. My own elderly grandmother loved it so much that she saw it three times in a theater that summer, which was practically unheard of in her later years (she also, inexplicably, loved the 1999 Mummy movie). It was a millennial DVD staple. I can recall everyone on my freshman dorm hall owning it and hearing it on regular rotation. As studio projects were getting bigger with more reliance on CGI, Gladiator felt like a refreshing reminder on how powerful old stories can be with some modern-day polish. Re-watching Gladiator twenty years later, it still resonates thanks to its tried-and-true formula of underdog vengeance.

We all love a good story where we follow a wronged party seek to right those wrongs, plus we all love a good underdog tale, and given the pomp and circumstance of the gladiatorial arena, it’s easy to see how this movie was engineered to be a success from the page. This isn’t a particularly new story. Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus mined the same territory with an even bigger scope, both in politics and in war, and there have been many movies covering the same history around the rise of Commodus, like 1964’s The Fall of the Roman Empire and The Two Gladiators. We’ve seen this kind of story before even in this setting but that doesn’t matter. The familiarity with a story isn’t a hindrance if the filmmakers take their story seriously and make an audience care about its characters. It all comes down to execution. As long as the filmmakers don’t get complacent and take that formula familiarity for granted, old stories can have the same power they had for decades because, deep down, cooked in their structure, they just work.

Gladiator gives us everything we need to know by the conclusion of its first act, introducing us to Maximus, showing his leadership and loyalty, giving us the strained father-son relationship with Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, the expectations of the son of his ascendancy, the regrets of the father and hope for a return to a Republic, the reluctance of Maximus to be more than a general of Rome, and finally after the murder of the old emperor, a decisive choice for Maximus that challenges his morals and responsibility. From there, screenwriters David Franzoni (Amistad), John Logan (The Aviator), and William Nicholson (Les Miserables) put our hero and villain on parallel tracks heading for a collision. Maximus rises through the ranks of gladiators and builds a name for himself, getting called to the major leagues of bloodsport, and Commodus schemes to have his old enemy killed with increasingly dangerous trials in the Coliseum. It’s a natural progression and escalation, which makes the storytelling satisfying as it carries on. Gladiator never had a finished script when they began filming, which has become more common with big budget tentpoles with daunting release dates and rarely does this work out well. However, this is the exception (the screenplay was even nominated for an Oscar). It should be stated that the events of Gladiator pay very little to the actual history but fidelity is not necessary to telling a compelling story (the real-life Commodus rose to power after dear old dad died from plague). Use what you need, I say.

Gladiator gives us everything we need to know by the conclusion of its first act, introducing us to Maximus, showing his leadership and loyalty, giving us the strained father-son relationship with Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, the expectations of the son of his ascendancy, the regrets of the father and hope for a return to a Republic, the reluctance of Maximus to be more than a general of Rome, and finally after the murder of the old emperor, a decisive choice for Maximus that challenges his morals and responsibility. From there, screenwriters David Franzoni (Amistad), John Logan (The Aviator), and William Nicholson (Les Miserables) put our hero and villain on parallel tracks heading for a collision. Maximus rises through the ranks of gladiators and builds a name for himself, getting called to the major leagues of bloodsport, and Commodus schemes to have his old enemy killed with increasingly dangerous trials in the Coliseum. It’s a natural progression and escalation, which makes the storytelling satisfying as it carries on. Gladiator never had a finished script when they began filming, which has become more common with big budget tentpoles with daunting release dates and rarely does this work out well. However, this is the exception (the screenplay was even nominated for an Oscar). It should be stated that the events of Gladiator pay very little to the actual history but fidelity is not necessary to telling a compelling story (the real-life Commodus rose to power after dear old dad died from plague). Use what you need, I say.

Ridley Scott was on an artistic hot streak during the start of the twenty-first century, directing three movies within one and a half years of release and earning two Oscar nominations. He wanted to veer Gladiator away from anything too cheesy of older swords-and-sandals epics, as reported. This isn’t about homoerotic wrestling with men in unitards (in Jerry Seinfeld voice: not that there’s anything wrong with that) and instead about the grit and superficial glory of Rome. The opening battle in Germania is meant to show Maximus in action but it also shows just how overpowering the Roman Empire was during this time period. They just massacre the remaining German tribe, and there’s a reason we don’t focus on battle strategy and instead on the chaos. The conclusion of the battle is a shaky camera mess of bodies and flames and dark shapes. It’s a bloody mess and not something to be glorified. Maximus is tired. His men are tired. Even Marcus Aurelius is tired of his decade-long conquering of a map, adding little inches to an already gargantuan territory. When is it all enough? When is war a self-perpetuating quagmire?

This same dismissive view over conquest and glory carries throughout. When Maximus becomes a slave, he must play the blood-thirsty appetites of the crowd to reach his goals. He disdains the theater of combat, the delaying of strikes simply to draw out the drama of two men fighting to the death. Later, these same venal interests of the mob form a protection for Maximus. He’s too popular to just be assassinated because the Roman people just love watching how he slays opponents. There’s an implicit condemnation of popular entertainment built around the suffering of others. Scott has a purpose for his depictions of violence, and you could even make the argument he is drawing parallels between the bloodthirsty crowds of the Coliseum and modern-day moviegoers screaming for violence. What are the human costs for this entertainment? It’s not explicitly stated, and some might even say this level of commentary for a movie awash in bloodshed makes any such condemnation hollow or hypocritical. Maybe. The violence feels like it has weight even when it can border on feeling like a video game stage with enemies to clear.

This same dismissive view over conquest and glory carries throughout. When Maximus becomes a slave, he must play the blood-thirsty appetites of the crowd to reach his goals. He disdains the theater of combat, the delaying of strikes simply to draw out the drama of two men fighting to the death. Later, these same venal interests of the mob form a protection for Maximus. He’s too popular to just be assassinated because the Roman people just love watching how he slays opponents. There’s an implicit condemnation of popular entertainment built around the suffering of others. Scott has a purpose for his depictions of violence, and you could even make the argument he is drawing parallels between the bloodthirsty crowds of the Coliseum and modern-day moviegoers screaming for violence. What are the human costs for this entertainment? It’s not explicitly stated, and some might even say this level of commentary for a movie awash in bloodshed makes any such condemnation hollow or hypocritical. Maybe. The violence feels like it has weight even when it can border on feeling like a video game stage with enemies to clear.

Crowe (The Nice Guys) was already making a name for himself as a rugged character actor in movies like L.A. Confidential and The Insider, but it was Gladiator that made him a Hollywood leading man, a title that he always seems to have felt uncomfortable with. Crowe wasn’t the first choice of Scott and the filmmakers (Mel Gibson turned Maximus down saying he was too old), but it’s hard to imagine another person in the role now. Crowe has a commanding presence in the film, an immediate magnetism, that you understand why men would follow him into hell. That flinty intensity plays into the action movie strengths, but there’s also a reflective side to the man, a sense of humor that can be surprising and rewarding. There’s more to Maximus than avenging his wife and child, and Crowe brings shades of complexity to an instantly iconic role. He finds the tired soul of Maximus when he could have simply been a kickass killing machine. Between Crowe’s three Best Actor nominations in a row from 1999-2001, I think he won for the wrong performance. It’s a shame Crowe hasn’t been nominated since, which seems downright absurd. People have forgotten what an amazing actor Crowe can be, singing voice notwithstanding (I need a sequel to Master and Commander please and thank you).

This was also a breakout role for Joaquin Phoenix (Her), who has risen to become one of the most celebrated and chameleon-like actors of his generation. The character of Commodus is your classic example of an entitled child who doesn’t understand why people don’t like him. He’s a sniveling villain prone to temper tantrums (“I am vexed. I am very vexed”). Much like his co-star, Phoenix finds layers to the character rather than resting on a stock villain characterization. He’s really the jealous son who envies the preference and love given to Maximus, first from his father, then from his widowed sister (Connie Nielsen), and then from the Roman people. He whines that they love Maximus in a way he will never deserve. It’s hard not to even see a Trumpian psychology to Commodus, a man not equipped for the position of power he occupies who longs for adulation he hasn’t earned. You can hate the man, but you might also feel sorry for him despite yourself. When he wants to be pompous, he can be hilarious (I adored his quick reaction shots to the theatrical combat). When he wants to be creepy, he can be terrifying. You can even see some of the broken pieces here that Phoenix would masterfully use to compose his Oscar-winning Joker performance.

This was also a breakout role for Joaquin Phoenix (Her), who has risen to become one of the most celebrated and chameleon-like actors of his generation. The character of Commodus is your classic example of an entitled child who doesn’t understand why people don’t like him. He’s a sniveling villain prone to temper tantrums (“I am vexed. I am very vexed”). Much like his co-star, Phoenix finds layers to the character rather than resting on a stock villain characterization. He’s really the jealous son who envies the preference and love given to Maximus, first from his father, then from his widowed sister (Connie Nielsen), and then from the Roman people. He whines that they love Maximus in a way he will never deserve. It’s hard not to even see a Trumpian psychology to Commodus, a man not equipped for the position of power he occupies who longs for adulation he hasn’t earned. You can hate the man, but you might also feel sorry for him despite yourself. When he wants to be pompous, he can be hilarious (I adored his quick reaction shots to the theatrical combat). When he wants to be creepy, he can be terrifying. You can even see some of the broken pieces here that Phoenix would masterfully use to compose his Oscar-winning Joker performance.

The supporting cast was gifted with great old actors getting one last victory lap. Richard Harris was so stately and grandfatherly that it got him the role of Dumbledore in the Harry Potter franchise. It also served as a great sendoff for Oliver Reed (Oliver!) as Proximo, the selfish, trash-talking former gladiator turned gladiator trainer. Reed died months into the production and before he had wrapped his part, requiring extensive reworking from the screenwriters (Logan was on set for much of the production to cater to the immediate day-to-day story needs). Scott used a body double and parlayed visual effects to recreate Reed’s face, much like what 1994’s The Crow was forced to do after the unfortunate death of its star, Brandon Lee. I kept looking for what moments would be Reed and what moments would be the CGI-enabled Reed double, and it was harder to determine than I thought, so nice job visual effects team. Reed had a reputation of being a carousing reprobate, so having a final performance that allowed him to tap into those old impulses plus the regrets of older age was a wonderful final match.

The other big takeaway upon my twenty-year re-watch was how recognizable and stirring Hans Zimmer’s famous score was, which lost the Oscar that year to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and that seems insane to me. Zimmer has been in a class all his own since the 90s with classic, instantly hum-able scores for True Romance, The Lion King, The Dark Knight, Inception, and The Pirates of the Caribbean, which borrows heavily from his theme for Gladiator. The score greatly adds to the excitement and majesty of the movie and can prove transporting by itself.

The other big takeaway upon my twenty-year re-watch was how recognizable and stirring Hans Zimmer’s famous score was, which lost the Oscar that year to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and that seems insane to me. Zimmer has been in a class all his own since the 90s with classic, instantly hum-able scores for True Romance, The Lion King, The Dark Knight, Inception, and The Pirates of the Caribbean, which borrows heavily from his theme for Gladiator. The score greatly adds to the excitement and majesty of the movie and can prove transporting by itself.

A truly bizarre post-script is the story of how the studio tried to develop a sequel. Gladiator was hugely successful but any sequel presented problems. Given the death of its star, following another character makes the most sense, and yet that’s not the direction the screenplay took. Eventually, the sequel to Gladiator was going to follow the ghost of Maximus as it travels through time including to modern-day. Just take a moment and dream of what could have been. Alas, we’ll likely never get time-traveling ghost Maximus now and we simply don’t deserve it as a society.

Reviewing my original film critique from 2000, I feel that my 18-year-old self was more entranced with making snappy, pithy blurbs than going into further detail on my analysis. My early reviews were far more declarative, saying something was good or bad and giving some detail but not dwelling on going deeper into the examination. This line, “The blood spills in the gallons and life and limb go flying enough your theater owner may consider setting down a tarp,” makes me cringe a little because it’s just trying too hard to be casually clever. I do enjoy the Mena Suvari rose petal joke. Still, I celebrated that a studio movie could emphasize its story first and foremost and my observations are still valid. I’m all but certain the only reason I knew who Steve Reeves was back then was because of his many appearances via Mystery Science Theater 3000 covering his cheesy swords-and-sandals films of old that Ridley Scott was so eager to avoid recreating (“Do you like films about gladiators?”)

Because the movie does so much so well, with some exceptional, it’s hard for me to rate Gladiator any lower than my initial grade of an A-, so that’s where I’m keeping it twenty years later. I think the national conversation has cooled on Gladiator, forgotten it because it wasn’t quite as audacious as other examples of early 2000s films, but it sets out to tell a familiar story on a big canvas and deserves its plaudits for somehow pulling it all off with style and gravity. It would be flippant to say Gladiator still slays the competition but it’s still mighty entertaining.

Re-View Grade: A-

The Ice Harvest (2005)

Imagine my surprise when I found out that a small crime novel I read years ago was getting the big Hollywood treatment. I read Scott Phillips’ The Ice Storm in one sitting back in 2003 during a plane trip from Ohio to San Diego. It was deliciously dark down to the very last page and I loved it, but then I am a sucker for a good crime story (check out Jason Starr’s Tough Luck and Hard Feelings if you are the same). The movie looked to be on the right track with names like John Cusack to star and Harold Ramis to direct. Ramis is responsible for starring, writing, or acting in or directing some of the most beloved comedies of the last 25 years including Ghostbusters, Groundhog Day, Stripes, and National Lampoon’s Vacation. That’s one illustrious comedic pedigree. So how could the movie go wrong?

Imagine my surprise when I found out that a small crime novel I read years ago was getting the big Hollywood treatment. I read Scott Phillips’ The Ice Storm in one sitting back in 2003 during a plane trip from Ohio to San Diego. It was deliciously dark down to the very last page and I loved it, but then I am a sucker for a good crime story (check out Jason Starr’s Tough Luck and Hard Feelings if you are the same). The movie looked to be on the right track with names like John Cusack to star and Harold Ramis to direct. Ramis is responsible for starring, writing, or acting in or directing some of the most beloved comedies of the last 25 years including Ghostbusters, Groundhog Day, Stripes, and National Lampoon’s Vacation. That’s one illustrious comedic pedigree. So how could the movie go wrong?

It’s Christmas Eve and Charlie Arglist (John Cusack) is a self-loathing attorney that works for some of the shadiest folks in Wichita, Kansas. One of those bad customers is mob boss Bill Guerrard (Randy Quaid) whom Charlie and his partner Vic (Billy Bob Thornton) have just swindled over $2 million from. Unfortunately for them, Wichita is hit by an ice storm that makes the roads haphazard to travel. The two will wait until the morning thaw and then hit the road with their booty. Vic reassures Charlie to just, “act normal.” This means many ventures to some of Wichita’s finest strip clubs with alluring names like Sweet Cage and Tease-O-Rama. Charlie has a sweet spot for Renatta (Connie Nielsen), a bombshell and the operator of the Sweet Cage. He’ll also have to drive his plastered friend Phil (Oliver Platt) around, who is regretting having married Charlie’s cold ex-wife. Charlie would love to sail off into the sunset with Renatta by his side but first he’ll have to survive the night and a mob enforcer (Mike Starr) is already on his trail.

The Ice Harvest feels like an episodic collection of ideas, too many of which have too little significance. The titular ice storm seems all but forgotten, only serving as a cheap plot device to keep our characters bottled up in the city. It has no bearing elsewhere on the plot. The reoccurring “As Wichita falls” passage has no payoff. The nosy police officer plotline looks like it might be building to something important but then is quickly disposed of. The Christmas setting has little impact except for giving the strippers something to complain about. The Ice Harvest wants to benefit from the juxtaposition of Christmas cheer with all these tawdry, violent asides and it just seems small and shallow. The movie also shifts the story’s time from 1979 to modern day one suspects just for the cheap out of cell phones.

The Ice Harvest feels like an episodic collection of ideas, too many of which have too little significance. The titular ice storm seems all but forgotten, only serving as a cheap plot device to keep our characters bottled up in the city. It has no bearing elsewhere on the plot. The reoccurring “As Wichita falls” passage has no payoff. The nosy police officer plotline looks like it might be building to something important but then is quickly disposed of. The Christmas setting has little impact except for giving the strippers something to complain about. The Ice Harvest wants to benefit from the juxtaposition of Christmas cheer with all these tawdry, violent asides and it just seems small and shallow. The movie also shifts the story’s time from 1979 to modern day one suspects just for the cheap out of cell phones.

Credit goes to Cusack for making his character as likable as he is. His character is a mob lawyer, a deadbeat dad, an increasingly drunk driver, and a man with his nose in whole lot of sleazy ventures, and yet you still pull for him to somehow succeed. Cusack, forever youthful, seems overly numb to all the horror around him and downplays the danger to a negative degree. Charlie seems like he’s in the wrong movie. Thornton plays yet another hedonistic louse and is quite good though not at his Bad Santa apex. He seems the most at ease with the physical comedy. Nielsen plays your typical femme fatale with a Veronica Lake haircut and breezy voice, which should both be instant red flags for students of film noir. The two men that steal the show are Platt and Quaid. Platt gives a brilliant uninhibited performance as quite possibly the drunkest man in movie history. Quaid is an honest surprise as a menacing mobster ruing the day he chose a criminal enterprise in Kansas. He chomps scenery with a violent exasperation that truly seems larger than life. This is a bad guy to fear and Quaid makes the most of his very limited screen time.

Ramis is out of his league here. The man cannot competently direct tension or action. Ramis doesn’t let the audience build suspicion because he’d much rather have characters just point-blank say, “Don’t trust this person” instead. He doesn’t give us time to piece clues of betrayal together so instead characters just keep running forward until they get smacked in the face by something made obvious. Ramis’ mishandling of tone really sinks the movie. The Ice Harvest doesn’t know whether it wants to be a thriller of a dark comedy and therefore just really sputters at both. The comedic elements and the thriller elements butt heads; because of the comedy the character never feel in danger, and because of the thriller/noir elements the characters and their situations never really seem funny. The Ice Harvest turns into some kind of two-headed beast that snaps at itself. I think maybe Ramis was watching Blood Simple and taking notes and then he accidentally taped over it with a Charles in Charge marathon and was at a loss.

P art of this problem is that the screenwriters don’t fully commit to the nastiness. Phillips’ novel is unrelentingly dark, cynical, and unsentimental and doesn’t give a damn if you like its characters. The movie, on the other hand, wants to get its hands dirty but is more interested in playing it safe. The film seriously reminded me of last year’s Surviving Christmas, another movie that wanted to be sweet and nasty and wound up just being really bad. You can feel The Ice Harvest reeling back several times to set up Charlie as a likable lad in over his head, going so far as a slightly contrived yet predictable finale. At least Bad Santa had the gusto to approach a happy ending on its own crude, unsentimental terms. Ramis needs to stick to broad comedies and leave the bleak neo-noir humor to the Coen brothers.

art of this problem is that the screenwriters don’t fully commit to the nastiness. Phillips’ novel is unrelentingly dark, cynical, and unsentimental and doesn’t give a damn if you like its characters. The movie, on the other hand, wants to get its hands dirty but is more interested in playing it safe. The film seriously reminded me of last year’s Surviving Christmas, another movie that wanted to be sweet and nasty and wound up just being really bad. You can feel The Ice Harvest reeling back several times to set up Charlie as a likable lad in over his head, going so far as a slightly contrived yet predictable finale. At least Bad Santa had the gusto to approach a happy ending on its own crude, unsentimental terms. Ramis needs to stick to broad comedies and leave the bleak neo-noir humor to the Coen brothers.

There are some plot elements from the book that just don?t work with this half-hearted adaptation. (Spoilers to follow for paragraph) At the very end of the movie Charlie has left the city with all the money and stops along the road to help a stalled camper. In the book, the camper backs up over him and kills him, thus ending with the ringing endorsement that crime doesn’t pay. It made sense, especially for a book that was dark to the very end. In the movie, the camper backs up and knocks him to the ground but doesn’t run him over. Charlie dusts himself off and that’s that. The scene feels pointless without fulfilling the end of the book. It doesn’t provide any last-second tension. Charlie just hops back in his car, dear hung over Phil pops up, and the two are set for one most excellent adventure. Unearned and misplaced happy ending? No thank you.

The Ice Harvest is only a mere 88 minutes long and yet the film still feels padded and draggy. The drunken Oliver Platt-heavy middle is a generously paced muddle, and though it’s rather funny it’s also rather extraneous. The Ice Harvest is really a handful of great moments that don?t add up to a satisfying whole. The movie is really episodic and too many of those episodes have little bearing on the plot. Character betrayals are spelled out to us and Ramis seems to lose interest in his own film as it slides further and further into dangerous territory. The Ice Harvest can’t commit to whatever it wants to be and the audience is the one to suffer. Read the book instead. It’s only 224 pages.

Nate’s Grade: C

One Hour Photo (2002)

Do we regularly invite strangers to view the picturesque and personal moments of our life like marriages, celebrations, and maybe even a handful of hastily conceived topless photos? Well we all do every time we drop off a roll of film for development.

Do we regularly invite strangers to view the picturesque and personal moments of our life like marriages, celebrations, and maybe even a handful of hastily conceived topless photos? Well we all do every time we drop off a roll of film for development.

Robin Williams continues his 2002 Tour of the Dark Side (Death to Smoochy, Insomnia) as way of Sy, your friendly photo guy working at your local Sav-mart superstore. Sy takes an intense artistic pride in the quality of prints he gives. He knows customers by name and can recite addresses verbatim. One family in particular Sy has become fond of is the Yorkins, mother Nina (Connie Nielsen), father Will (Michael Vartan) and nine-year-old Jake. The Yorkins have been coming to Sav-mart and Sy for over 11 years to have their photos developed. He tells Nina that he almost feels like Uncle Sy to the family. For Sy, the Yorkins are the ideal postcard family with perennially smiling faces and the happiest of birthdays. He fantasizes about sharing holidays with them and even going to the bathroom in their posh home.

Sy is an emotionally suppressed and deeply lonely man caught in his delusions. In one of the eerier moments of the film we see that Sy has an entire wall made up of hundreds of the Yorkin’s personal pictures. When Sy attempts to become closer to the objects of his infatuation that’s when things begin to unravel at a serious pace. The more Sy learns that the Yorkins are not the perfect family he yearns for the more he tries to correct it and at any cost.

Sy is an emotionally suppressed and deeply lonely man caught in his delusions. In one of the eerier moments of the film we see that Sy has an entire wall made up of hundreds of the Yorkin’s personal pictures. When Sy attempts to become closer to the objects of his infatuation that’s when things begin to unravel at a serious pace. The more Sy learns that the Yorkins are not the perfect family he yearns for the more he tries to correct it and at any cost.

One Hour Photo is an impressive film debut by music video maven Mark Romanek (best known for the NIN “Closer” video). Romanek also wrote the darkly unrepentant story as well. One Hour Photo is a delicate voyage into the workings of Sy’s instability with lushly colorful metaphors. Romanek’s color scheme is a lovely treat, with vibrant colors popping out and Sy’s life being dominated by cold, sterilized whites. His direction is chillingly effective.

This may be the first time we can truly say Robin Williams has not merely played a version of Robin Williams in a movie. Sy’s thick glasses and thinning peroxide-like hair coupled with an array of facial pocks allow us to truly forget that the man behind the mask is Mork. His performance is unnerving and engrossing. The supporting cast all work well. Nielsen (Gladiator) is a sympathetic wife even if her hair looks like it was cut with her eyes closed. Vartan (Vaughn on ABC’s wonderful Alias) plays understandably wary of Sy’s friendliness. The great Gary Cole has a small role as Sav-mart’s manager who grows tired of Sy’s outbursts and peculiarities.

One Hour Photo is rife with nervous moments and titters. Williams almost has an uneasy predatory feel to him when left alone with Jake. The greatest achievement the film has is that is depicts the scariest person youll ever see, sans hockey mask, and by the end of the film you actually feel degrees of warmth for this odd duck.

One Hour Photo is rife with nervous moments and titters. Williams almost has an uneasy predatory feel to him when left alone with Jake. The greatest achievement the film has is that is depicts the scariest person youll ever see, sans hockey mask, and by the end of the film you actually feel degrees of warmth for this odd duck.

Not everything clicks in Romanek’s dark opus. A late out-of-left-field revelation by Sy feels forced and needlessly tacked on. The Yorkin family photos all appear to be taken by a third party, since the majority of them involve all three of them in frame. The climax to One Hour Photo also feels anything but climactic.

A compellingly creepy outing, One Hour Photo is fine entertainment with beautiful visuals and a haunting score. And maybe, in the end, it really does take an obsessive knife-wielding stalker to make us realize the importance of family.

Nate’s Grade: B

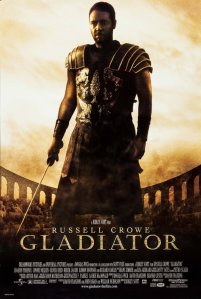

Gladiator (2000)

Director Ridley Scott has given the world of cinema some of its most unforgettable visual experiences. But can Scott breath new life into a genre whose heyday was when a badly dubbed Steve Reeves oiled his chest and wrestled loincloth-clad extras in the 1950s?

Director Ridley Scott has given the world of cinema some of its most unforgettable visual experiences. But can Scott breath new life into a genre whose heyday was when a badly dubbed Steve Reeves oiled his chest and wrestled loincloth-clad extras in the 1950s?

The year is roughly 180 AD and Rome is just finishing up its long-standing assault on anything that moves in the European continent. General Maximus (Russell Crowe) merely wants to retire back to his loving family and get away from the doom and war that has plagued his life. This is made all the more difficult when the ailing Emperor bypasses his treacherous son Commodus (Joaquin Phoenix) and decides to crown Maximus as the Defender of Rome. Because of this Commodus rises to power through bloody circumstances and has Maximus assigned to execution and his family crucified. You’d think crucifixion would be so passé by now. Maximus escapes only to be sold into slavery and bought by a dirt-run gladiator training school. As he advances up the chain and learns the tricks of the primal sport he seeks but vengeance for his fallen family.

Gladiator is an absorbing and sweeping spectacle of carnage and first-rate entertainment. The action is swift and ruthlessly visceral. The first movie in a long time to literally have me poised on the edge of my seat. The blood spills in the gallons and life and limb go flying enough your theater owner may consider setting down a tarp.

What Gladiator doesn’t sacrifice to the muscle of effects and action is storytelling. Are you listening George Lucas? Gladiator may unleash the beast when the rousing action is loose, but this is coupled with compelling drama and complex characters. Phoenix may at first seem like a snotty brat with an unhealthy eye for his sister (Connie Nielsen), but the further Gladiator continues the more you see in his eyes the troubled youth who just wants the love of his father that was never bestowed to him. Maximus is a devoted family man who regularly kisses clay statues of his family while away, and must ceremoniously dust himself with the earth before any battle.

What Gladiator doesn’t sacrifice to the muscle of effects and action is storytelling. Are you listening George Lucas? Gladiator may unleash the beast when the rousing action is loose, but this is coupled with compelling drama and complex characters. Phoenix may at first seem like a snotty brat with an unhealthy eye for his sister (Connie Nielsen), but the further Gladiator continues the more you see in his eyes the troubled youth who just wants the love of his father that was never bestowed to him. Maximus is a devoted family man who regularly kisses clay statues of his family while away, and must ceremoniously dust himself with the earth before any battle.

The acting matches every sword blow and chariot race toe-for-toe. Russell Crowe marks a first-rate staple of heroism. Every calculating glare he exhibits shows the compassion and ferocity of this warrior. He becomes a rare breed – an action hero who can think and actually act. Oliver Reed, in what sadly was his last role, turns in a splendid and charismatic turn as the head of the gladiator school of Fine Arts and Carnage. Mysteriously everyone carries a British accent closer to them then a toga two sizes too small. Even Crowe who is nicknamed “The Spaniard” speaks like he walked out of Masterpiece Theater.

The effects and visuals are a sumptuous feast. The aerial shots of Rome and the Coliseum are simply breath taking. Gladiator rivals American Beauty for the most rose petals used in a movie, except in this one they don’t shoot out of Mena Suvari’s breasts.

Ridley Scott’s track record may be hit or miss but Gladiator is definitely one sorely not to be missed.

Nate’s Grade: A-

Reviewed 20 years later as part of the “Reviews Re-View: 2000” article.

Mission to Mars (2000)

Mission to Mars begins with a team of astronauts making the first manned mission to the red planet. Unfortunately things go… um, bad, and thus with no knowledge of any survivors and the six month time period it takes to travel to Mars, NASA sends out a rescue mission. More things go bad.

Mission to Mars begins with a team of astronauts making the first manned mission to the red planet. Unfortunately things go… um, bad, and thus with no knowledge of any survivors and the six month time period it takes to travel to Mars, NASA sends out a rescue mission. More things go bad.

The setting is supposed to be 2020 but everything looks exactly like 1980. In the future there seems to be heavy reliance on product placement. From Dr. Pepper, to M&Ms, to having the damn Mars buggy plastered with Penzoil and Kawasaki. Are these astronauts Earth’s interstellar door-to-door salesmen? I was half expecting them to nix the American flag and firmly plant one for Nike. Maybe the future’s just this way because they drink from square beer.

Director Brian DePalma unleashes fantastic special effect after another, but they can only sugarcoat the bitter taste Mars leaves in your mouth. Mission to Mars is tragically slow paced, full of interchangeable and indiscernible characters, and begging for some kind of insight. Don Cheadle and Gary Sinise prove that no matter how great an actor you are, when you’re given cheesy sci-fi dialogue, it’s still cheesy.

The fault lies with the more than three screenwriters and DePalma himself. Plain and simple, DePalma has lost his touch. His good days (The Untouchables) are clearly behind him on his new downward slide. Mars in any other director’s hands would no doubt be different — and that’s no bad thing. DePalma’s style of appropriations rips off the earlier, better, and more insightful 2001 and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

Mars is surprisingly and sadly devoid of any tension or suspense. The suspense was likely killed in the efforts to portray an “accurate and realistic NASA manned planetary exploration.” Yet the scientific inaccuracies in this “accurate” portrayal are far too numerous to mention – let alone remember all of them. You cannot have tension during a problematic situation when the score is blaring church organs.

One can suspend belief and enjoy movies but Mars is a listless journey toward sentimental other-worldly beings that just want a hug. Can we have them destroying our cities again? Pretty please.

Nate’s Grade: C

You must be logged in to post a comment.