Blog Archives

Snack Shack (2024)

The coming-of-age sub-genre is a familiar and well-worn formula, but with the right filmmaker and voice, it can become refreshingly alive once again, like hearing your favorite song covered by an exciting different artist. Snack Shack is an exuberantly charming movie about one summer with 14-year-old best friends who are constantly running money making schemes and hustles. They overbid to run the concession stand at their community pool, but the best buds are entrepreneurial whizzes and turn the snack shack into a smashing success. There’s plenty of familiar genre elements, from bullies, parents they’ll have more appreciation and understanding from at summer’s end, parties and self-discovery, crushes and jealousies that will test their limits of loyalty; there might not be anything new during these 110 minutes, but it’s the nostalgic authenticity and verve from writer/director Adam Carter Rehmeier (Dinner in America) that makes the movie shine. The movie is practically bristling with details that feel so well-realized and genuine. You’ll enjoy spending time in this world and with these characters, reliving the summer of 1991 in Nebraska. Gabriel LaBelle (The Fabelmans) is fantastic as Moose, more the live-wire, always-smiling, charismatic smooth-talker of the two friends. Every second he’s onscreen makes you inch closer to the screen. I don’t think some of the downer plot turns late in the movie feel like a fit and are there to form the Hard Truths experiences meant to shake the innocence of youth. For a movie this jubilant and sunny, it feels like an abrupt tonal swerve that’s more deferential to genre expectations than the previous vibe of the movie. Despite some minor missteps, the good times cannot be thwarted and Snack Shack is a funny and refreshingly retro peon to being young.

The coming-of-age sub-genre is a familiar and well-worn formula, but with the right filmmaker and voice, it can become refreshingly alive once again, like hearing your favorite song covered by an exciting different artist. Snack Shack is an exuberantly charming movie about one summer with 14-year-old best friends who are constantly running money making schemes and hustles. They overbid to run the concession stand at their community pool, but the best buds are entrepreneurial whizzes and turn the snack shack into a smashing success. There’s plenty of familiar genre elements, from bullies, parents they’ll have more appreciation and understanding from at summer’s end, parties and self-discovery, crushes and jealousies that will test their limits of loyalty; there might not be anything new during these 110 minutes, but it’s the nostalgic authenticity and verve from writer/director Adam Carter Rehmeier (Dinner in America) that makes the movie shine. The movie is practically bristling with details that feel so well-realized and genuine. You’ll enjoy spending time in this world and with these characters, reliving the summer of 1991 in Nebraska. Gabriel LaBelle (The Fabelmans) is fantastic as Moose, more the live-wire, always-smiling, charismatic smooth-talker of the two friends. Every second he’s onscreen makes you inch closer to the screen. I don’t think some of the downer plot turns late in the movie feel like a fit and are there to form the Hard Truths experiences meant to shake the innocence of youth. For a movie this jubilant and sunny, it feels like an abrupt tonal swerve that’s more deferential to genre expectations than the previous vibe of the movie. Despite some minor missteps, the good times cannot be thwarted and Snack Shack is a funny and refreshingly retro peon to being young.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Didi (2024)

It feels slightly strange when you acknowledge that coming-of-age movies have long-surpassed your own age of adolescent personal discovery. With Sundance indie Didi, we’ve now brought that time frame up to 2008, where we follow the 13-year-old Chris (Izac Wang), a first-generation Taiwanese-American kid trying to flirt with his junior high crush, get better at skateboarding, edit YouTube videos that people might actually want to see, and perhaps make some new friends during the summer before high school begins. This is one of those movies that lives or dies by its slice-of-life details and sense of authenticity. Writer/director Sean Wang does an excellent job placing the audience in the position of his biographical avatar, Chris. We feel his discomfort trying to navigate the different cultural expectations of home life and school life, the perils of trying to step outside your comfort zone and be rewarded rather than embarrassed. This is compounded by Chris having to endure and brush aside the stereotypes his peers project onto him for being Asian-American. The problem with the movie is that our main character is kind of a twit. He’s so harsh and unfair to his long-suffering mother (Lust, Caution‘s Joan Chen) that his own friends eventually complain about his rude behavior. In a moment of awkward discomfort, he calls his friend’s crush “a whore,” and then describes how he and his friend messed around with the corpse of a squirrel once. He also pees in his older sister’s lotion bottle. The whole “befriending cool skateboarders” storyline goes nowhere, nor does it open up some deeper understanding of our character and his wants, talents, or capabilities. Didi’s real distinct angle could have been growing up in the Internet age, and there it too feels lacking. It all feels a little like we’re spending too much time with the wrong family member. The put-upon mother would have been an even more intriguing person to explore, especially as she yearns to be an artist, deals with her bratty kids, an overbearing mother-in-law living with them without a kind word to say, and a husband half the world away busy working. Getting stuck with the angsty kid feels disappointing.

It feels slightly strange when you acknowledge that coming-of-age movies have long-surpassed your own age of adolescent personal discovery. With Sundance indie Didi, we’ve now brought that time frame up to 2008, where we follow the 13-year-old Chris (Izac Wang), a first-generation Taiwanese-American kid trying to flirt with his junior high crush, get better at skateboarding, edit YouTube videos that people might actually want to see, and perhaps make some new friends during the summer before high school begins. This is one of those movies that lives or dies by its slice-of-life details and sense of authenticity. Writer/director Sean Wang does an excellent job placing the audience in the position of his biographical avatar, Chris. We feel his discomfort trying to navigate the different cultural expectations of home life and school life, the perils of trying to step outside your comfort zone and be rewarded rather than embarrassed. This is compounded by Chris having to endure and brush aside the stereotypes his peers project onto him for being Asian-American. The problem with the movie is that our main character is kind of a twit. He’s so harsh and unfair to his long-suffering mother (Lust, Caution‘s Joan Chen) that his own friends eventually complain about his rude behavior. In a moment of awkward discomfort, he calls his friend’s crush “a whore,” and then describes how he and his friend messed around with the corpse of a squirrel once. He also pees in his older sister’s lotion bottle. The whole “befriending cool skateboarders” storyline goes nowhere, nor does it open up some deeper understanding of our character and his wants, talents, or capabilities. Didi’s real distinct angle could have been growing up in the Internet age, and there it too feels lacking. It all feels a little like we’re spending too much time with the wrong family member. The put-upon mother would have been an even more intriguing person to explore, especially as she yearns to be an artist, deals with her bratty kids, an overbearing mother-in-law living with them without a kind word to say, and a husband half the world away busy working. Getting stuck with the angsty kid feels disappointing.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Inside Out 2 (2024)

Of all the Pixar hits, 2015’s Inside Out is one of the better movies to develop a sequel for, and thankfully Inside Out 2 is a solid extension from the original. The internal world of Riley’s burgeoning sense of self is so deeply imaginative and creatively rewarding, balancing slapstick and broad humor with a deeper examination of abstract concepts and human psychology (Freud would have loved this movie… or hated it… or just thought about his mother). The unique setting was made so accessible by the nimble screenplay that the viewer was able to learn the rules of this setting and how interconnected the various parts are. While not being as marvelously inventive as its predecessor, nor as poignant (R.I.P. Bing Bong), Inside Out 2 is a heartwarming and reaffirming animated movie that will work for all ages.

Riley is now turning thirteen years old and in the midst of puberty. That means new emotions, and Joy (voiced by Amy Poehler) has to learn to work well with her co-workers, such as Envy, Embarassment, and Ennui. The biggest new addition is Anxiety (voiced by Maya Hawke) who wants to prepare Riley for her life ahead, which seems especially rocky now that Riley knows her two best friends will be going to a different school. A weekend trip to hockey camp becomes Riley’s opportunity to test drive the “new Riley,” the one who impresses the cool older kids and gains their acceptance. This will force Riley to have to determine which set of friends to prioritize, the new or the old, and whether the goofy, kind version can survive to middle school or needs to be snuffed out.

With the sequel, there aren’t any dramatically new wrinkles to the world building already established. We don’t exactly discover any new portions of Riley’s mind, instead choosing to place most of the plot’s emphasis on another long journey back to home base. This time the other core emotions get to stick around with Joy, each of them proving useful during a key moment on the adventure. The externalization of the emotions invites the viewer to feel something toward feelings themselves. When Joy, at her lowest, laments that maybe a hard realization about growing up is that life will simply have less joy, it really hit me. Part of it was just the sad contemplation that accepting adulthood means accepting a life with less happiness, but a big part was teaching this concept to children and being unable to provide them the joy they deserve. Since the 2015 original, my life has gone through different changes and now I watch these movies not just as an individual viewer recalling life as a former adolescent figuring things out, but now I also come from the perspective of a parent with young children, including one turning thirteen. The development of the mind of this little growing person is a heavy responsibility given to people who are, hopefully, up to that very herculean task. We can all try our best, but recognizing limitations is also key. The kids have to have the freedom to be themselves and not pint-sized facsimiles of a parent.

The emotions inside Riley’s mind are featured like internal surrogate parents, tending to the development of Riley’s emotions, morals, and personality. They presumably want what’s best for her, there just happen to be opposing interpretations of what that exactly means, which leads to the majority of conflict with Anxiety. However, there’s also an understanding that Riley has to do things on her own and be able to make mistakes and learn from them. Inside Out 2 is ultimately about accepting the limitations of providing guidance. Joy and Anxiety are both trying to steer Riley down a deliberate path they think is best, but Riley needs to discover her own path rather than have it programmed for her. I appreciated that Anxiety is not treated as some dangerous one-dimensional villain hijacking Riley’s brain. Much like sadness, there is a real psychological purpose for anxiety, to keep us alert and prepared. Now that can certainly go into overdrive, as demonstrated throughout Inside Out 2, including a realistic depiction of a panic attack. It’s about finding balance, though one person’s balance will be inordinately different from another. The stakes may be intentionally low in this movie, all about making the hockey team and being welcomed by the popular girl she may or may not be crushing over (more on that later), but the focus is on the sense of who Riley chooses to be through her life’s inevitable ups and downs. It’s about our response to change as much as it is our response to the presence of anxiety.

Inside Out 2 also answers a thorny world-building question that the original creators never thought to go into greater detail. It’s established in the 2015 original that even the adults have the same five core emotions manning their brain battle stations: Disgust, Fear, Sadness, Anger, and Joy. So if adults only see these same emotions, what happens to those new puberty emotions? Do they go away? As an adult, do we gradually work through anxiety and embarrassment to the point where they are no longer present (this is where every adult can wryly laugh)? There’s an emotion introduced as Nostalgia, depicted as a kindly grandmother so eager to remember the ways things were. Joy tells Nostalgia to leave, as it’s not time for her to be developed yet until Riley is older. This one moment clears up the world-building question; the emotions don’t leave, they just sit out for periods of time like bench players waiting to be called into the big game. And just like that, it all works and makes sense. I wonder what other new emotions make their appearances later in life. Resentment? Choosing to rather die in authority rather than give up an iota of power to a younger generation? Sorry, that last one was more directed at those stubborn folks clinging to Congressional offices.

There is some sight narrative and thematic redundancy here. The first movie was about learning the importance of accepting sadness as a vital part of the human condition and how we can process our emotional states. It was about Joy learning that not every moment in life can or should be dominated by joy, and that the other emotions are also necessary functions. With the sequel, we have a starting point where Joy is picking and choosing what memories are worthy of being remembered, banishing the “bad moments” to the back of Riley’s mind, forming a cavernous landfill of junked memories. It’s treading some pretty similar ground, prioritizing one set of memories or emotions over others wherein the ultimate lesson is that repression in all forms is unhealthy and robbing one of the necessary tools for self-acceptance and growth. This is further epitomized by a trip to one of these memory vaults where Riley’s Deep Dark Secret is willfully imprisoned. The movie proper never comes back to this self-loathing figure, and the revelation could have really supported the overall message of self-acceptance. Pixar could have done something really special here, like having Riley coming to terms with being bisexual/queer, and that perhaps something we may personally agonize over as a horrifying secret could, once shared, be far from the dreaded life-destroying culprit our minds make it out to be. This would have really worked with the perceived lower stakes of the movie, naturally elevating the ordinary to the profound, as life can often unexpectedly become. Alas, the Deep Dark Secret is just a setup to an underwhelming post-credits joke – womp womp. That’s it? Again, if you’re going to tread the familiar thematic grounds about the dangers of repression, at least give us something bigger to reach than the same lesson that all emotions have a place.

The first Inside Out was a masterpiece. That’s a hard act to follow. This sequel, of which we can all assume there will be more given its billion-dollar box-office, is a solid double to the original’s home run of entertainment. It’s not among their best but it’s one of their better non-Toy Story sequels. Inside Out 2 is a heartwarming winner.

Nate’s Grade: B

I Saw the TV Glow (2024)/ The Watchers (2024)

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

I Saw the TV Glow is a strange experience by design, a hallucinatory ode to early 1990s television, coming of age sagas, feeling out of place in one’s own body and mind, and on a Lynchian dream logic wavelength that few filmmakers occupy. From a plot standpoint, Owen (Justice Smith) is a shy kid who looks up to an older girl at school, Maddy (Bridget Lundy-Paine), and they share a love for the TV show The Pink Opaque, a tween-aimed horror series in the vein of Goosebumps or Are You Afraid of the Dark?, which ultimately might be real after all. This movie exists more on a slippery emotional plane than on its story sense. Writer/director Jane Schoenbrun (We’re All Going to the World’s Fair) has created an allegory for self-actualization and self-acceptance through a love of 90s nostalgia and that transitional time of being young and just seeing the cusp of what adulthood promises for the good, the bad, and the mundane. The recreation of the SNICK-era television is perfect, and I loved the little glimpses of these horror monsters taking on new nightmarish incarnations. I wanted the movie to explore its premise more, that this old TV show might be real and posing a danger that only they would uncover. It’s really more a pathway for the characters to explore their selves, what animates them, what confuses them, what provides a sense of community. It’s a movie about the perils of loneliness and finding an outlet, a life raft, whatever that may be, and for Owen it’s this TV show. He connects more with this world than the real one, and when he revisits it later as an adult, it doesn’t live up to his memory. It’s a weird movie but it’s designed for weird kids, or weird adults who used to be weird kids, who found kinship through weird media. It’s a slow and provocative experience that asks you to give yourself over to its vision, but Schoenbrun also makes that engagement quite accessible. While existing as a clear trans allegory, I Saw the TV Glow is open to any outsider who felt unsure of themself and their body and their place in the universe. It’s about obsession and the price of holding onto said childhood obsessions, even if they prove disappointing in your adulthood. It doesn’t offer any general answers or catharsis and is kept on the slowest of slow burns. I began daydreaming of the less arty version of its spooky premise, but that’s simply not going to be this movie. I Saw the TV Glow is impressively personal and surreal and obtuse, but by the end I was hoping for a little more of a foundation to hold onto and its ideas to be fully realized.

Nate’s Grade: B

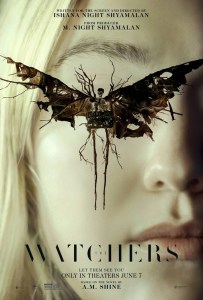

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

The expansion of the M. Night Shyamalan creative dynasty has begun. While based on a 2022 novel by A.M. Shine, The Watchers is brought to us primarily by Ishana Shyamalan, who makes her feature directing debut and adapted the screenplay. It has a buzzy premise that feels at home in a Shyamalan movie, namely a young woman (Dakota Fanning) who stumbles into a strange location with captive people telling her she cannot leave or her life will be in danger from monsters. The group of survivors have to “perform” for their unseen watchers, staring into a two-way mirror inside a closed room. There are certain rules that are hazy and unevenly applied: don’t go out after dark, never turn your back to the mirror, don’t go into the creatures’ subterranean dwelling. This poses an intriguing mystery for a while as the movie unpacks and reveals more about this world and the creatures. However, The Watchers ultimately cannot help feeling like an over-extended episode of a sci-fi anthology TV series like Black Mirror or maybe even Shyamalan’s own Apple Plus series Servant (Ishana wrote and directed several episodes). There just isn’t enough here. The revelations do not sustain our emotional and intellectual investment. Once it’s revealed what the monsters are, I kept waiting for extra levels of twists and turns, and there really aren’t any. Once we settle into Act Three, the movie becomes more or less about housekeeping and gaining acceptance. The whole reason the protagonist is on her journey is to deliver a bird in a cage, and every time this thing keeps appearing even so late into the movie, while she’s running for her life but cannot forget about the caged bird, I felt like laughing. It’s a case of inelegantly finding a way for the visual metaphor (the bird is her!) to continue being tied to the plot after it long stopped making sense. Likewise, there are cutaways to the captives watching a Love Island/Big Brother-stye reality TV show, but little is made as far as commentary on communal voyeurism, so they just come across as little odd comic asides. The movie loses some serious momentum once we get to the convenient info dump sequence (a Shyamalan family favorite: scientist vlogs) and you realize there are no more tricks to deliver. It’s disappointing that a movie with such potent folklore atmosphere becomes a lackluster variation on The Village.

Nate’s Grade: C

Are You There God? It’s Me, Margret (2023)

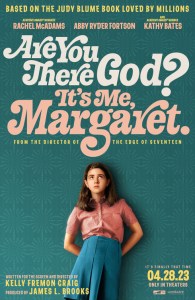

When is it not weird for a 41-year-old man to cry about a young woman getting her first period? When you’re watching the film adaptation of Judy Blume’s long-celebrated coming-of-age novel, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. Blume waited almost fifty years before signing over the rights to writer/director Kelly Fremon Craig, whose 2016 movie Edge of Seventeen showed a downright Blume-esque combination of authenticity, good humor, and grace. That trusted vision is evident with how natural and deeply felt the movie comes across. We’ve had numerous coming-of-age tales since Blume’s influence, so I worried that maybe it would feel outdated or surpassed, but the movie taps into a great reservoir of empathy, bringing to relatable light the uncertainty of puberty, of fitting in, and trying to navigate the ever-approaching adult world. Usually these kinds of movies invite the viewer to reflect back upon their own young adult experiences, which I did even though I was never a teenage girl, but I had my own awkward and vulnerable moments too. I really enjoyed that Craig’s movie makes ample time for the adults too, which is where my relatability was prioritized. Watching Rachel McAdams try and explain why her parents disowned her for marrying a Jewish man is a powerfully affecting moment of an adult trying to explain a very hard truth to their child. The movie is affectionate and uplifting and earnest without being too cloying. It’s a pleasant and wholesome movie that showcases Craig as an agile filmmaker who deserves more opportunities and that even fifty years later, being an adolescent girl is still the same old awkward agony.

When is it not weird for a 41-year-old man to cry about a young woman getting her first period? When you’re watching the film adaptation of Judy Blume’s long-celebrated coming-of-age novel, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. Blume waited almost fifty years before signing over the rights to writer/director Kelly Fremon Craig, whose 2016 movie Edge of Seventeen showed a downright Blume-esque combination of authenticity, good humor, and grace. That trusted vision is evident with how natural and deeply felt the movie comes across. We’ve had numerous coming-of-age tales since Blume’s influence, so I worried that maybe it would feel outdated or surpassed, but the movie taps into a great reservoir of empathy, bringing to relatable light the uncertainty of puberty, of fitting in, and trying to navigate the ever-approaching adult world. Usually these kinds of movies invite the viewer to reflect back upon their own young adult experiences, which I did even though I was never a teenage girl, but I had my own awkward and vulnerable moments too. I really enjoyed that Craig’s movie makes ample time for the adults too, which is where my relatability was prioritized. Watching Rachel McAdams try and explain why her parents disowned her for marrying a Jewish man is a powerfully affecting moment of an adult trying to explain a very hard truth to their child. The movie is affectionate and uplifting and earnest without being too cloying. It’s a pleasant and wholesome movie that showcases Craig as an agile filmmaker who deserves more opportunities and that even fifty years later, being an adolescent girl is still the same old awkward agony.

Nate’s Grade: B+

The Holdovers (2023)

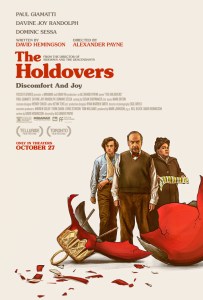

Oscar-winning director Alexander Payne and Paul Giamatti re-team for a poignant and crowd-pleasing holiday movie about outcasts sharing their vulnerabilities with one another over the last week of 1970. Giamatti stars as Paul Hunham, a rigid history teacher at an all-boys academy who just happens to be liked by nobody including his colleagues. He gets the unfortunate duty of staying on campus during the Christmas break and watching over any students who cannot return home for the holidays. Angus (Dominic Sessa) is the last student remaining, a 15-year-old with a history of lying, defiance, and on the verge of expulsion. The other holdover member is Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) as the kitchen staff forced to feed them, a woman whose own adult son recently died in Vietnam. The teacher and student butt heads as they try and co-exist without other supervision, eventually connecting once they lower their defenses and attempt to see one another as flawed human beings with real hurts and disappointments. It’s a simple movie about three different characters from very different experiences pushing against one another and finding common ground. It’s a relationship movie that has plenty of wry humor and strong character beats from debut screenwriter David Hemingson. There may not be a larger theme or thesis that emerges, but being a buddy dramedy about hurt people building their friendships is still a winning formula with excellent writing, directing, and acting working in tandem, which is what we have with The Holdovers. It’s a slice of-life movie that makes you want bigger slices, especially for Mary’s character who thought having her son attend the same prep school would set him up for a promising future (he was denied college admission and thus deferral from the draft). It’s a beguiling movie because it’s about sad and lonely people over the holidays, each experiencing their own level of grief, and the overall feel is warm and fuzzy, like a feel-good movie about people feeling bad. That’s the Alexander Payne effect, finding an ironic edge to nostalgia while exploring hard-won truths with down-on-their-luck characters. The Holdovers is an enjoyable holiday comedy with shades of bitterness to go along with the feel-good uplift. It’s Payne’s Christmas movie and that is is own gift to moviegoers.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem (2023)

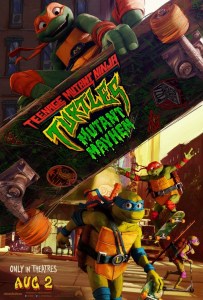

As an elder millennial, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles have been a formative franchise for me. I grew up on the cartoon, got the toys for Christmas, died endlessly during the shockingly hard underwater stage of their Nintendo video game, and generally have a soft spot in my 80s nostalgia for the likes of Leonardo, Donatello, Raphael, and Michelangelo, plus their surrogate father, Master Splinter. Apparently Seth Rogen felt the same way, and he and his writing partner Evan Goldberg have spearheaded a new animated variation of TMNT that just so happens to also be co-written and directed by the man behind my favorite film of 2021, The Mitchells vs. The Machines. It was a recipe to guarantee my personal enjoyment, and Mutant Mayhem thusly delivered. The biggest selling point for me was how lovingly realized the “teenage” part of the title was, getting a foursome of actual adolescents to portray our heroes, and using high school experience about acceptance and fitting in as effective and even poignant parallels. I loved just hanging out with these characters, who view their surrogate dad (voied by Jackie Chan) with a mixture of love and embarrassment, and who want to be accepted by a world predisposed to finding them monstrous. Naturally, becoming crime-fighting heroes is their best method for winning over the public, with a young and aspiring journalist April O’Neil (The Bear‘s Ayo Edebiri) hoping to improve her own social standing at school by breaking the existence of these unknown mutants. The comedy is robust and layered while allowing for nice character details and moments, giving each turtle their own satisfying arc. The action is fun and inventively staged while still being thematically relevant. The vocal cast is great, and the young actors are tremendous together, sparking an enviable improvisational energy that made me smile constantly. The art style has an intentional messiness to it, like smeared colored pencil drawings, and the imperfections are themselves part of the vast visual appeal. It’s a family movie that will succeed with old fans and new, and Mutant Mayhem is the best film depiction yet of the famous heroes in a half-shell.

As an elder millennial, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles have been a formative franchise for me. I grew up on the cartoon, got the toys for Christmas, died endlessly during the shockingly hard underwater stage of their Nintendo video game, and generally have a soft spot in my 80s nostalgia for the likes of Leonardo, Donatello, Raphael, and Michelangelo, plus their surrogate father, Master Splinter. Apparently Seth Rogen felt the same way, and he and his writing partner Evan Goldberg have spearheaded a new animated variation of TMNT that just so happens to also be co-written and directed by the man behind my favorite film of 2021, The Mitchells vs. The Machines. It was a recipe to guarantee my personal enjoyment, and Mutant Mayhem thusly delivered. The biggest selling point for me was how lovingly realized the “teenage” part of the title was, getting a foursome of actual adolescents to portray our heroes, and using high school experience about acceptance and fitting in as effective and even poignant parallels. I loved just hanging out with these characters, who view their surrogate dad (voied by Jackie Chan) with a mixture of love and embarrassment, and who want to be accepted by a world predisposed to finding them monstrous. Naturally, becoming crime-fighting heroes is their best method for winning over the public, with a young and aspiring journalist April O’Neil (The Bear‘s Ayo Edebiri) hoping to improve her own social standing at school by breaking the existence of these unknown mutants. The comedy is robust and layered while allowing for nice character details and moments, giving each turtle their own satisfying arc. The action is fun and inventively staged while still being thematically relevant. The vocal cast is great, and the young actors are tremendous together, sparking an enviable improvisational energy that made me smile constantly. The art style has an intentional messiness to it, like smeared colored pencil drawings, and the imperfections are themselves part of the vast visual appeal. It’s a family movie that will succeed with old fans and new, and Mutant Mayhem is the best film depiction yet of the famous heroes in a half-shell.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Gray Matter (2023)

As a lifelong film fan, I’ve always been fascinated with the trials and tribulations of the many seasons of Project Greenlight. It began in 2001 as a contest shepherded by Matt Damon, Ben Affleck, and irritable producer Chris Moore to select the best submitted script and turn it into a movie. The process would also be documented at every stage by TV cameras for an HBO documentary series, but this is an organization defined by its chaos and mistakes, which make for spellbinding schadenfreude television and rather disappointing movies. Each season tried to retool. Season one winner Peter Jones was more a writer than a director and not fully ready when he was thrust to also direct his winning script, so season two had separate submissions to select a winning writer and a winning director to pair. Season three realized that the coming-of-age indies of the first two seasons (Stolen Summer, The Battle of Shaker Heights) didn’t exactly ignite the box-office, so the intent was a more commercial genre script, which ended up becoming the monster siege thriller, Feast. Season four, coming nearly ten years later, decided that the commercial script needed to come from a more trusted and studio-backed source rather than amateurs. That source: Pete Jones, now having become a co-writer to some Farrelly Brothers comedies. That season only sought to select a director, having now completely ditched the screenwriting aspect from the start of the contest, but the winning director ditched the approved script to make a middling comedy feature of his own short film (The Leisure Class). Now, many years later, HBO Max (or now just… Max, because somebody thinks “HBO” lacks brand value) has rebooted Project Greenlight, again, and has another more commercially-minded script to serve the eventual directing winner, this time among a team of ten female finalists. So after twenty years and five movies, what has Project Greenlight proven? Good TV doesn’t mean good movies.

Gray Matter will forever be known as “the Project Greenlight movie,” and if it wasn’t for that series, we wouldn’t be seeing this movie because it’s so generic and underwritten, which, having spent the day binging through the new Greenlight season, are the same problems that all the many producers were complaining about with the script. Well, you folks picked this script, right?

Aurora (Mia Isaac) is a 16-year-old who just wants to feel like a normal teenager. Her mom, Ayla (Jessica Frances Dukes), is afraid she won’t be able to defend herself in this scary world. They’re a mother-daughter psionic duo, exhibiting mind powers. After a tragedy away from home, Aurora finds herself in a weird complex run by Derek (Garret Dillahunt), a mysterious authority figure who says he’s trying to find all the psionics he can to help them better understand their unique abilities. Aurora suspects her captors don’t really have her best interest at heart.

That plot description above sounds like a hundred other YA-tinged stories, from The Darkest Minds to Firestarter to the X-Men TV show The Gifted, which also co-starred Dillahunt. It’s a fine starting point but the story and characters need to find ways to better personalize this formula, and that’s where Gray Matter falters. It’s all too surface-level, from the mother-daughter relationship, to the determination of Ayla, to the self-actualization of our teen. It’s not that you’ve seen it before, it’s that you’ve seen it before much better in so many other stories.

The story pieces are present that can be developed for a more engaging and character-centric sci-fi drama. There is potential here. I think more could be made about Ayla’s past connections to this psionic complex, but instead of being offered to co-chair it as an administrator, it would have been more interesting if she had been younger, a pregnant teen, and her unborn baby was the course of great speculation for the facility, especially being the child of two psionics. This would add an extra layer of urgency why Ayla felt she had to leave as well as why Aurora would be more coveted than other psionics. It could also easily explain why Aurora would be more powerful than any other psionic. It would also personalize the sacrifice of Ayla as well as her paranoia about the lengths they will be hunted. We needed more time with Ayla as a character because once the daughter gets kidnapped around the Act One break, she’s seen more in flashback and fantasy sequences than reality. If this is going to be the emotional core of the movie, then we need to flesh out the mother and the scenes between them. As demonstrated in the movie, Aurora is here to push her daughter, tell her she isn’t ready, then restrict her but also not really restrict her, as Aurora seems to sneak out every night to meet boys. If this woman is so paranoid, why is she alternating between being a strict gatekeeper and a free-range parent? It didn’t make sense. She’s keeping her child out of school and the public and constantly moving, but hey, go ahead and fraternize with these teenagers supposedly behind my back?

It’s also a shame that our protagonist is such a boring blank. The puberty/super power allegory has been prevalent for decades, but for a movie that literally spends so much of its time inside the mind of its main character, she’s unfortunately too underdeveloped and unexplored. She’s just kind of present for too many of her scenes rather than an active participant. This is partly from the nature of the script, where Aurora has to learn about her powers and the history of psionics, but why does the first act of the movie resort to repeating this exposition? We have one scene where mom is explaining powers and what’s at stake, and then twenty minutes later we have another scene of Derek explaining powers and what’s at stake. The biggest problem with Gray Matter is that its central character feels like an afterthought of a simple yet empty empowerment message. It’s about a young woman coming into her own power, externally and internally, but it’s also expressed under such generic terms. What do we know about Aurora? She wants a “normal life” but what does this constitute? Does she resent her mother’s rules? Has she rebelled in the past? What really animates her? What is her sense of purpose? I don’t know, which diminishes all the sequences of her running in terror, and that dominates the middle hour. I wish the script had started with her sneaking out, hanging out with these kids who consider her “that weird homeschool girl,” and then when things go wrong we have to learn with what we see rather than sitting through multiple people trying to explain the world and rules. It would be a better shock when things go wrong, and the added time would allow more breathing room to try and flesh out Aurora before she’s defined by her powers.

Another aspect that needed further re-examination was the nature of the psionic powers. The plot needed to better define the rules of these powers, which are quite varied. We begin with the powers mostly being telekinetic, the ability to move things with one’s mind. Then it jumps into telepathy, the ability to speak through one’s mind, then read the minds of others, then project mental structures, then working all the way to teleportation. There is a good scene where Derek is impressed by Aurora’s ability to hide her thoughts with a false setting construct, and I enjoyed him pointing out the giveaway details, like a character reading a book that is only ever the same page. That was a smart scene that better visualized the powers. However, the characters talk too broadly about the powers in sweeping proclamations. I think the movie could have improved had the story ditched more of the powers and settled down on one, with Aurora having the ability to manifest more than one power being a sign of her extraordinary identity.

As a low-budget genre movie, Gray Matter looks like a professional movie and has good actors doing their best. Debut director Meko Winbush has made a genre movie that looks practically indistinguishable from other disposable Hollywood genre thrillers, and maybe on a sliding scale, feeling and looking like a generic sci-fi thriller might be a success in the history of Project Greenlight. But I doubt all the many people who lent their labor and names to this project were hoping for it to be on par with a forgettable streaming entity eventually crushed by a library of content. Winbush presents enough visual polish that could lead her to future work, something that has also plagued many of the director winners from seasons past (Jason Mann, the season four winner, has one feature credit after The Leisure Class, serving as DP to a 2019 Slovenian movie). It’s hard to feel what exactly people could get passionate about with Gray Matter, and they just waited for a rewrite to supply all the missing emotional engagement and introspection and fun that was absent. Once again, the finished film ends up being a disappointing season finale to a train wreck of reality TV.

Nate’s Grade: C

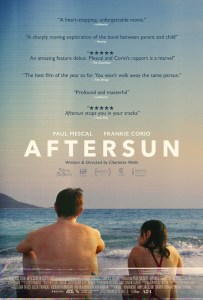

Aftersun (2022)

I feel slightly like a movie philistine for my opinion concerning Aftersun. This indie drama has become one of the critical darlings of 2022, enough so that there may even be some serious Oscar buzz starting to foment. It’s a movie with a strong beating heart and rich in authentic details and naturalistic performances, a movie that feels practically like a home video ripped from the past. However, while I appreciated the artistry on display, I kept waiting for the actual “movie” to form, the reason this story was given its big screen status. Aftersun is a lyrically felt movie but also one I wish had a more sustained plot to better develop its dramatic potential.

It’s the mid 1990s and Sophie (Frankie Corio) is staying at a seaside Turkish resort with her father, Calum (Paul Mescal). Her parents are separated and she has a complicated relationship with her father, who covers up his own spiraling sadness by trying to be the “fun dad.” At eleven years of age, Sophie is feeling that awkward middle-ground of not being a child but still not being fully grown, and over her vacation, she observes her world and father with new eyes.

The strength of the movie is the richness of its characters and world, with each moment feeling like it was plucked straight from the memory of debut writer/director Charlotte Wells. The movie is framed as a home video of Sophie’s and makes clever use of her narrating footage, allowing the perspective to be directed literally by its source. It’s also interesting because there’s a degree of performance for Sophie, as the presence of a camera usually goads people into acting differently, to play up to the camera, and this channels Sophie into being a goofy performer. Off camera, she’s less prone to making jokes and being broad and silly. She jokes with her father, chiding him for his “advanced age” and other such topics, but there’s more hesitancy and relatable awkwardness with Sophie in real life. Her dad says she should go introduce herself to other children at the resort, to make friends and have partners in play, and she scoffs that at eleven she’s “not a little kid anymore.” She wants to hang out with the older teens and eavesdrop on their conversations, not fully aware of their meaning and context, as that hurried desire that young children have to cast aside their childhoods in favor of immediate maturity. There isn’t any defining experience at this resort, no direct humiliation or formative wisdom to point to. It’s more the small moments of a young girl between the different phases of her life. Sophie comes across as an achingly realistic portrayal of adolescence and the yearning for real connections.

The majority of the movie is about the relationship between father and daughter, and I was waiting for the movie to hit me hard, especially as I’ve recently become the stepfather to an eleven-year-old daughter. The relationship is there but there’s nothing too demonstrative of what is going on between these two people. It’s unclear whether this might be the last time Sophie will see her father for some time, or whether the divorce was recent and still a sore subject, or anything of extra significance. It just feels like a vacation, and that’s as it’s presented, and maybe that’s the larger unspoken point of Wells, that the mundane moments only become more cherished in hindsight or when we realize they were the last moments before whatever happened.

I think Wells might suspect the narrative on its own is missing that larger significance, so distributed throughout the movie are flashes from a rave with an older woman, and it’s revealed later that this thirty-something woman is actually Sophie as an adult, and a new parent herself. This juxtaposition then serves as an ongoing film-length Kuleshov Effect. This cinematic effect, named after the Soviet filmmaker from one hundred years ago, reasons that placing two objects together forms an implicit connection or reaction, so seeing a picture of soup and then a man looking forward might convey hunger or a picture of a coffin and then a man looking forward might convey grief. By this juxtaposition, we’re left to infer larger meaning and processing, as older Sophie is looking back on these scenes as distant memories. We’re left to deduce what that means to her, what new insights she has as an adult looking back, and what has happened since, and I’m sure some viewers will find this a tantalizing human puzzle to unpack. For me, it felt like extra homework without the key elements to make the depictions dramatically involved.

The acting is another laudible element that adds to the overall authenticity of the movie. Corio is a star in the making and has a natural screen presence. Mescal (God’s Creatures, Normal People) carries much of the film’s larger thematic weight, and I kept waiting for some small moment that would provide more meaning behind the surface level. Mescal is very good and his dynamic with his young co-star feels heartwarming and genuine. I enjoyed spending time with both of these actors, and while they charmed me, I kept wishing that they had a little more material to flex.

Aftersun is an easy movie to admire and see what Wells was going for, reflecting perhaps some biographical experience and something that every adult can insert themself and think about their own parental relationships, wondering what sort of things they took for granted during those innocent days of childhood and the acknowledgement of the quiet struggles of parents. It’s filmed beautifully and acted with sensitivity and plenty of understatement, the kind of thing that indie film fans and critics vaunt as revelatory filmmaking. It’s a solid movie that only comes to 90 minutes, but it also felt like I was watching a stranger’s home movies without context.

Nate’s Grade: B

The Fabelmans (2022)

Steven Spielberg has been the most popular film director of the last fifty years but he’s never turned the focus squarely on himself, and that’s the draw of The Fabelmans, a coming-of-age drama that’s really a coming-of-Spielberg expose. The biographical movie follows the Fabelman family from the 1950s through the late 60s as Sammy (our Steven Spielberg avatar) becomes inspired to be a moviemaker while his parents’ marriage deteriorates. As a lifelong lover of movies and a childhood amateur filmmaker, there’s plenty here for me to connect with. The fascination with recreating images, of chasing after an eager dream, of working together with other creatives for something bigger, it’s all there and it works. I’m a sucker for movies about the assemblage of movie crews, those found families working in tandem. However, the family drama stuff I found less engaging. Apparently Sammy’s mother (Michelle Williams) is more impulsive, spontaneous, and attention-seeking, and may have some un-diagnosed mental illness at that, whereas his father (Paul Dano) is a dry and boring computer engineering genius. I found the family drama stuff to be a distraction from the storylines of Sammy as a budding filmmaker experimenting with his art and Sammy the unpopular new kid at high school harassed for being Jewish. There are some memorable scenes, like a girlfriend’s carnal obsession with Jesus, and a culmination with a bully that is surprising on multiple counts, but ultimately I found the movie to be strangely remote and lacking great personal insight. This is why Spielberg became the greatest filmmaker in the world? I guess. I’ll credit co-writer Tony Kushner (West Side Story, Lincoln) for not making this what too many modern author biopics have become, a barrage of inspirations and connections to their most famous works (“Hey Steven, I want you to meet our neighbor, Ernest Thalberg, or E.T. as we used to call him back at Raiders U.”). The Fabelmans is a perfectly nice movie, with solid acting, and the occasional moment that really grabs hold of you, like a electrifying meeting with a top Hollywood director in the film’s finale. For me, those moments were only too fleeting. It’s a family drama I wanted less family time with and more analysis on its creator.

Steven Spielberg has been the most popular film director of the last fifty years but he’s never turned the focus squarely on himself, and that’s the draw of The Fabelmans, a coming-of-age drama that’s really a coming-of-Spielberg expose. The biographical movie follows the Fabelman family from the 1950s through the late 60s as Sammy (our Steven Spielberg avatar) becomes inspired to be a moviemaker while his parents’ marriage deteriorates. As a lifelong lover of movies and a childhood amateur filmmaker, there’s plenty here for me to connect with. The fascination with recreating images, of chasing after an eager dream, of working together with other creatives for something bigger, it’s all there and it works. I’m a sucker for movies about the assemblage of movie crews, those found families working in tandem. However, the family drama stuff I found less engaging. Apparently Sammy’s mother (Michelle Williams) is more impulsive, spontaneous, and attention-seeking, and may have some un-diagnosed mental illness at that, whereas his father (Paul Dano) is a dry and boring computer engineering genius. I found the family drama stuff to be a distraction from the storylines of Sammy as a budding filmmaker experimenting with his art and Sammy the unpopular new kid at high school harassed for being Jewish. There are some memorable scenes, like a girlfriend’s carnal obsession with Jesus, and a culmination with a bully that is surprising on multiple counts, but ultimately I found the movie to be strangely remote and lacking great personal insight. This is why Spielberg became the greatest filmmaker in the world? I guess. I’ll credit co-writer Tony Kushner (West Side Story, Lincoln) for not making this what too many modern author biopics have become, a barrage of inspirations and connections to their most famous works (“Hey Steven, I want you to meet our neighbor, Ernest Thalberg, or E.T. as we used to call him back at Raiders U.”). The Fabelmans is a perfectly nice movie, with solid acting, and the occasional moment that really grabs hold of you, like a electrifying meeting with a top Hollywood director in the film’s finale. For me, those moments were only too fleeting. It’s a family drama I wanted less family time with and more analysis on its creator.

Nate’s Grade: B

You must be logged in to post a comment.