Monthly Archives: October 2025

The Long Walk (2025)

The quality of Stephen King adaptations may be the scariest legacy for publishing’s Master of Horror. The best-selling author has given us many modern horror classics but the good King movies are more a minority to what has become a graveyard of schlocky productions. Everyone has their own top-tier but I think most would agree that for such a prolific author, you can probably count on two hands the “good to great” King movies and have a few fingers to spare. 2025 is a bountiful year for King fans, with the critically-acclaimed The Life of Chuck, the remake of The Monkey, the upcoming remake of The Running Man, which was originally set in a nightmarish future world of… 2025, and now The Long Walk. Interestingly, two of these films are adaptations from King’s Richard Bauchman books, the pseudonym he adopted to release more novels without “diluting the King brand,” or whatever his publisher believed. The Long Walk exists in an alternative America where teen boys compete to see who can last the longest in a walking contest. If they drop below three miles per hour, they die. If they step off the paved path, they die. If they stop too often, they die. There is no finish line. The game continues until only one boy is left.

The Long Walk is juiced with tension. It’s like The Hunger Games on tour. (director Francis Lawrence has directed four Hunger Games movies) I was shocked at how emotional I got so early in the movie, and that’s a testament to the stirring concept and the development that wrings the most dread and anxiety from each moment. Just watching a teary-eyed Judy Greer say a very likely final goodbye to her teenage son Ray (Cooper Hoffman), contemplating what those final words might be if he never returns to her, which is statistically unlikely since he’s one of 50 competitors. How do you comprise a lifetime of feeling, hope, and love into a scant few seconds? It’s an emotionally fraught opening that only paves the way for a consistently emotionally fraught journey. In essence, you’re going along on this ride knowing that 49 of these boys are going to be killed over the course of two hours, and yet when the first execution actually takes place, it is jarring and horrifying. The violence is painful. From there, we know the cruel fate that awaits any boy that cannot follow the limited rules of the contest. The first dozen or so executions are given brutish violent showcases, but as the film progresses and we become more attached to the ever-dwindling number of walkers, the majority of the final executions happen in the distance, out of focus, but are just as hard-hitting because of the investment. Every time someone drops, your mind soon pivots to who will be next, and if you’re like me, there’s a heartbreak that goes with each loss. From there, it becomes a series of goodbyes, and it’s much like that super-charged opening between mother and son. Each person dropping out becomes another chance to try and summarize a lifetime, to communicate their worth in a society that literally sees them as disposable marketing tools. I was genuinely moved at many points, especially as Ray takes it upon himself to let the guys know they had friends, they will be remembered, and that they too mattered. I had tears in my eyes at several points. The Long Walk is a grueling experience but it has defiant glimmers of humanity to challenge the prevailing darkness.

I appreciated that thought has been taken to deal with the natural questions that would arise from an all-day all-night walkathon. What happens when you have to poop? What happens when you have to sleep? The screenplay finds little concise examples of different walkers having to deal with these different plights (it seems especially undignified for so many to be killed as a result of uncontrollable defecation). There’s a late-night jaunt with a steep incline, which feels like a nasty trap considering how sleep-deprived many will be to keep the minimal speed requirement. That’s an organic complication related to specific geography. It’s moments like this that prove how much thought was given to making this premise as well-developed as possible, really thinking through different complications. I’m surprised more boys don’t drop dead from sheer exhaustion walking over 300 miles without rest over multiple days. I am surprised though that after they drop rules about leaving the pavement equals disqualification and death that this doesn’t really arise. I was envisioning some angry walker shoving another boy off the path to sabotage him and get him eliminated. This kind of duplicitous betrayal never actually happens.

There’s certainly room for larger social commentary on the outskirts of this alternative world. King wrote the short story as a response to what he felt was the senseless slaughter of the Vietnam War. In this quasi-1970s America, a fascist government has determined that its workforce is just too lazy, and so the Long Walk contest is meant as an inspiration to the labor to work harder. I suppose the argument is that if these young boys can go day and night while walking with the omnipresent threat of death, then I guess you can work your factory shift and stop complaining, you commie scum. The solution of more dead young men will solve what ails the country can clearly still resonate even though we’re now four decades removed from the generational mistakes of the Vietnam War. The senselessness of the brutality is the point, meant to confront a populace growing weary with The Way Things Are, and as such, it’s a malleable condemnation on any authority that looks to operate by fear and brutality to keep their people compliant. There are some passing moments of commentary, like when the occasional onlooker is sitting and watching the walkers, drawing the ire of Ray who considers these rubberneckers to a public execution. They’re here for the blood, for the sacrifices, for the thrill. It’s risible but the movie doesn’t really explore this mentality except for some glancing shots and as a tool to reveal different perspectives.

Let’s talk about those leads because that’s really the heart of the movie, the growing friendship and even love between Ray and Pete (David Jonsson). They attach themselves early to one another and form a real sense of brotherhood, even dubbing each other the brother they’ve never had before. They’re the best realized characters in the movie and each has competing reasons for wanting to win. For Ray, it’s about a sense of misplaced righteousness and vengeance. For Pete, it’s about trying to do something better with society. His whole philosophy is about finding the light in the darkness but he is very clear how hard living this out can be on a daily basis. It’s a conscious choice that requires work but a bleak universe needs its points of light. Of course, as these gents grow closer to one another, saving each other at different points, the realization sets in that only one of these guys is going to make it across the proverbial finish line. We’re going to have to say goodbye to one of them, and that adds such a potent melancholy to their growing friendship, that it’s a relationship destined to be meaningful but transitional, a mere moment but a lifetime condensed into that moment. It’s easy to make the connection between this shared camaraderie built from overwhelming danger to soldiers being willing to die for their brothers in arms. Hoffman (Licorice Pizza) and Jonsson (Alien: Romulus) are both so immediately compelling, rounding out their characters, so much so that the whole movie could have been a 90-minute Richard Linklater-style unbroken conversation between the great actors and I would’ve been content.

My one reservation concerns the ending and, naturally, in order to discuss this I’ll be dealing with significant spoilers. If you wish to remain pure, dear reader, skip to the final paragraph ahead. It should be no real surprise who our final two contestants are because the filmmakers want us to really agonize over which of these two men will die for the other. Since we begin with Ray being dropped off, we’re already assuming he’s going to be the eventual winner. He’s got the motivation to seek vengeance against the evil Major who killed his father for sedition by educating Ray about banned art. He’s also been elevated to our lead. Even Pete has a monologue criticizing his friend for ever getting involved when he still has family. Pete has no family left and he has ideals to change the system. The screenplay seems to be setting us up for Pete being a change agent that forces Ray to recognize his initial winning wish of vengeance is selfish and myopic for all the bad out there in this warped society. It seems like Pete is being set up to influence Ray to think of the big picture and perhaps enact meaningful change with his winning wish. There’s even a couple of moments in the movie Pete directly saves Ray, going so far as to purposely kneel to allow Ray the opportunity to win. There’s also the Hollywood meta-textual familiarity of the noble black character serving as guide for the white lead to undergo meaningful change. It all feels thoroughly fated.

Then in a surprise, Ray pulls the same stunt and purposely stops so his buddy can win by default. As Ray dies, he admits that he thinks Pete was the best equipped to bring about that new world they were talking about. He dies sacrificing his own vengeance for something larger and more relevant to the masses. And then Pete, as per his winning wish, asks for a rifle, shoots and kills the Major, thus fulfilling Ray’s vendetta, and walks off. The end. The theme of thinking about something beyond personal grievance to help the masses, to enact possible change, is thrown away. So what was it all about? The carnage continues? It seems like thematic malpractice to me that the movie is setting up its two main characters at philosophical odds, with one preaching the value of forgoing selfish wish-fulfillment for actual change. The character arc of Ray is about coming to terms not just with the inevitability of his death but the acceptance of it because he knows that Pete will be the best person to see a better world. The fact that Pete immediately seeks bloody retribution feels out of character. The Long Walk didn’t feel like a story about a guy learning the opposite lesson, that he should be more selfish and myopic. It mitigates the value of the sacrifice if this is all there is. Furthermore, it’s strange that the bylaws of this whole contest allow a winner to murder one of the high-ranking government officials. Even The Purge had rules against government officials and emergency medical technicians being targeted (not that people followed those rules to the letter). Still, it calls into question the reality of this deadly contest and its open-ended rewards. If a winner demanded to go to Mars, would the nation be indebted to see this through no matter the cost? Suddenly contestant wishes like “sleep with ten women” seem not just banal but a derelict of imagination.

Affecting and routinely nerve-racking, The Long Walk is an intense and intensely felt movie. I was overwhelmed by tension at different points as well as being moved to tears at other points. While its dystopian world-building might be hazy, the human drama at its center is rife with spirit and life, allowing the audience to effortlessly attach themselves to these characters and their suffering. I feel strongly that the very end is a misstep that jettisons pertinent themes the rest of the movie had been building, but it’s not enough to jettison the power and poignancy of what transpires before that climactic moment. The Long Walk has earned its rightful place in the top-tier of Stephen King adaptations.

Nate’s Grade: B+

A House of Dynamite (2025)

Director Kathryn Bigelow’s first movie in eight years plays to her strengths with a dynamite ensemble cast trying to process a ticking clock of doom and their dwindling options. It’s an incredibly taut and thrilling movie elevated by Bigelow’s penchant for later-career verisimilitude. A nuclear missile is launched from an Asian country (North Korea? Russia? It’s never clarified) and heading for the American Midwest. The movie replays the chain of events three times and in real-time, first with the initial discovery of the missile and those in charge of launching counter defenses to take it out (a character describes the difficulty as “shooting a bullet with a bullet”). Then with the higher military brass debating whether to launch pre-emptive strikes against foreign countries making moves. Finally, with the president who hasn’t been seen up until this point, keeping the identity of the actor a surprise. He has to make the final decision of what to do as the missile looms and loss of life seems inevitable. I was fairly enthralled by the immediate pacing and the fraught conversations over doomsday planning. It felt like a modern-day and terrifying version of Fail Safe. There’s even room for some human stories here as people contemplate what might be the end, like trying to reach a loved one by phone and summarize a lifetime of feelings for closure, or debating whether or not to stay or leave the incoming danger. Because of the repeated structure of the screenplay, it holds out the missile striking or not striking until the very end. What will the president do? Is it as another character dubs a choice between suicide and surrender? And then…

Director Kathryn Bigelow’s first movie in eight years plays to her strengths with a dynamite ensemble cast trying to process a ticking clock of doom and their dwindling options. It’s an incredibly taut and thrilling movie elevated by Bigelow’s penchant for later-career verisimilitude. A nuclear missile is launched from an Asian country (North Korea? Russia? It’s never clarified) and heading for the American Midwest. The movie replays the chain of events three times and in real-time, first with the initial discovery of the missile and those in charge of launching counter defenses to take it out (a character describes the difficulty as “shooting a bullet with a bullet”). Then with the higher military brass debating whether to launch pre-emptive strikes against foreign countries making moves. Finally, with the president who hasn’t been seen up until this point, keeping the identity of the actor a surprise. He has to make the final decision of what to do as the missile looms and loss of life seems inevitable. I was fairly enthralled by the immediate pacing and the fraught conversations over doomsday planning. It felt like a modern-day and terrifying version of Fail Safe. There’s even room for some human stories here as people contemplate what might be the end, like trying to reach a loved one by phone and summarize a lifetime of feelings for closure, or debating whether or not to stay or leave the incoming danger. Because of the repeated structure of the screenplay, it holds out the missile striking or not striking until the very end. What will the president do? Is it as another character dubs a choice between suicide and surrender? And then…

Spoiler…

the movie just ends. I’m spoiling to protect you, dear reader. It’s not an ambiguous ending. There is no ending. There is no conclusion. I was flabbergasted. It’s like they lopped off the last twenty minutes. How could they do this? It completely ruins the movie for me and the whole experience becomes one of those distaff “we just want you to think” experiments that don’t function as a fully-developed movie. A House of Dynamite (coined from a podcast the president listened to) is a thriller that goes up in smoke.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Good Boy (2025)

This is the first movie I can think of that might have a vested interest in opening its title with something usually reserved at the very very end of credits: the animal cruelty disclaimer. It seems barbaric now, but decades ago, film productions didn’t give much care for the care of their animal actors. In the old days, especially at the height of Westerns, horses would just die by the dozens and sometimes be literal cannon fodder like in 1980’s Heaven’s Gate. Nowadays, productions are monitored for animal cruelty and make every effort to tell their stories without harming anyone, human and animal. Good Boy is a novel take on a familiar horror concept. It’s a haunted house movie about a nefarious life-sucking specter. It’s also completely told from the point of view of the family pet. It’s a common horror trope to have the animals sensing supernatural danger before their respective owners finally wise up, it’s another to base your entire movie on that perspective. That’s what director/co-writer Ben Loenberg put together over the course of three years, training his dog Indy to be the star of his debut feature film. While the film feels more like an empathy experiment than a fully developed movie, it’s an interesting twist that made me rethink familiar horror movie staples. Here’s a helpful spoiler to set your minds at ease: the dog lives, folks.

This is the first movie I can think of that might have a vested interest in opening its title with something usually reserved at the very very end of credits: the animal cruelty disclaimer. It seems barbaric now, but decades ago, film productions didn’t give much care for the care of their animal actors. In the old days, especially at the height of Westerns, horses would just die by the dozens and sometimes be literal cannon fodder like in 1980’s Heaven’s Gate. Nowadays, productions are monitored for animal cruelty and make every effort to tell their stories without harming anyone, human and animal. Good Boy is a novel take on a familiar horror concept. It’s a haunted house movie about a nefarious life-sucking specter. It’s also completely told from the point of view of the family pet. It’s a common horror trope to have the animals sensing supernatural danger before their respective owners finally wise up, it’s another to base your entire movie on that perspective. That’s what director/co-writer Ben Loenberg put together over the course of three years, training his dog Indy to be the star of his debut feature film. While the film feels more like an empathy experiment than a fully developed movie, it’s an interesting twist that made me rethink familiar horror movie staples. Here’s a helpful spoiler to set your minds at ease: the dog lives, folks.

Indy is a golden retriever and just the bestest boy. His owner, Todd (Shane Jensen), is going through a lot. Todd is suffering from a fatal illness and has returned to his grandfather’s home in the country. Todd’s sister is worried over his deteriorating mental and physical state and also believes that the old family home is haunted by a sinister presence that contributed to their grandfather’s demise. What’s a dog to do?

It’s an interesting choice to have a dog as our main character because it’s both limiting as well as coursing with dramatic irony. Firstly, we know it’s a movie, and the dog is just a dog and doesn’t know its owners are making art by being purposely weird. So many animal performances are like candid camera exercises (cue think pieces arguing that the dog could not really give consent to being terrorized for art). Telling your story from only what a dog is privy to will naturally limit the extent of the story. We can overhear snippets of conversations to draw inferences but the movie is making a value judgement that its audience will fill in the blanks of its familiar ghost story. This is the filmmakers at peace with their story being hazy and familiar and underdeveloped. They’re sacrificing clarity for adhering to their artistic vision, but because it’s the whole relevant sticking point of the movie, I think they made the right call.

It’s an interesting choice to have a dog as our main character because it’s both limiting as well as coursing with dramatic irony. Firstly, we know it’s a movie, and the dog is just a dog and doesn’t know its owners are making art by being purposely weird. So many animal performances are like candid camera exercises (cue think pieces arguing that the dog could not really give consent to being terrorized for art). Telling your story from only what a dog is privy to will naturally limit the extent of the story. We can overhear snippets of conversations to draw inferences but the movie is making a value judgement that its audience will fill in the blanks of its familiar ghost story. This is the filmmakers at peace with their story being hazy and familiar and underdeveloped. They’re sacrificing clarity for adhering to their artistic vision, but because it’s the whole relevant sticking point of the movie, I think they made the right call.

Alas, the dog is a limited perspective to tell a realistic story. However, the sense of dramatic irony is what helps add layers to the viewing. We see the dog know more but also simultaneously less than the humans. It senses the ghostly presence that the humans are ignorant of, but it doesn’t know why humans do their human things any more than any other non-human creature (we are puzzling). It makes for an experience where we are aware of what the dog knows but also simultaneously aware of what the dog doesn’t know. It makes for an interesting experience allowing the audience to empathize with our poor pooch but also recognize the dangers that it doesn’t and recognize the dangers that it’s trying to warn its owner over.

The perspective is a gimmick, sure, but it reminds me of last year’s In a Violent Nature, another indie horror project that took a familiar premise and turned it on its head through a canny choice of point of view. In that movie, we were presented the teenage slasher movie but from the beleaguered perspective of the zombified behemoth stalking the woods and trying to run into those mischievous teens. It was an experimental turn for a sub-genre that had been done to death by the conclusion of the 1980s, and that choice of perspective made it more reflective and contemplative as the viewer was forced to reconsider our relationship with these kinds of movies during the extended walks. Good Boy doesn’t go that philosophical distance, but its change of perspective refreshes the old tropes of the haunted house story.

Is Good Boy scary? Not really, but I actually don’t think that’s the point of the exercise either. The purposely underdeveloped story rests on familiar tropes, which cues the audience to place their attention less on the plot, rules, and explanations and more on empathizing with the dog. Because of this creative choice it can create tension whenever we feel like the dog is confused, alarmed, or threatened. While the filmmakers do a decent job of crafting a potent sense of mood with such a low-budget, I doubt few will characterize the movie as genuinely scary. However, what’s scary is what might happen to this good boy and his own emotional fragility trying to understand forces and choices beyond his capacity. I will say to the horror aficionados who also happen to be ardent animal lovers, there is another ghost dog that used to belong to the dead grandfather who met a tragic end, but other than that, Indy isn’t truly harmed. Still, I found the resolution to the movie, including the very final image, unexpectedly poignant and a reminder that dogs are so inherently loyal that we honestly don’t deserve them as a species.

Is Good Boy scary? Not really, but I actually don’t think that’s the point of the exercise either. The purposely underdeveloped story rests on familiar tropes, which cues the audience to place their attention less on the plot, rules, and explanations and more on empathizing with the dog. Because of this creative choice it can create tension whenever we feel like the dog is confused, alarmed, or threatened. While the filmmakers do a decent job of crafting a potent sense of mood with such a low-budget, I doubt few will characterize the movie as genuinely scary. However, what’s scary is what might happen to this good boy and his own emotional fragility trying to understand forces and choices beyond his capacity. I will say to the horror aficionados who also happen to be ardent animal lovers, there is another ghost dog that used to belong to the dead grandfather who met a tragic end, but other than that, Indy isn’t truly harmed. Still, I found the resolution to the movie, including the very final image, unexpectedly poignant and a reminder that dogs are so inherently loyal that we honestly don’t deserve them as a species.

Dogs are inherently empathetic beings, just ask any dog owner, so it’s easy to sympathize with this little guy trying to do his best to be the good boy he is. He just wants some pets and to cuddle with his human. He doesn’t know his owner is suffering from a chronic lung condition. He doesn’t know the strange man in black ooze creeping along the shadows isn’t another strange person. Our dog just knows things aren’t right. Naturally, without narration, our protagonist is going to be limited by what he can emote, and yet the filmmakers do a superlative job of getting the best performance out of their four-legged star. Through the judicious editing and planning, it really feels like this little guy is giving a performance, enough so that animal lovers might squirm occasionally in their seats. When the ghost is taking over Todd and he’s mean to Indy, I felt so bad for this little guy (he doesn’t know it’s all pretend). There are some wonderfully expressive close-ups, and while it’s entirely the Kulushov effect and I’m projecting meaning into a performance that isn’t actually there, that’s also the intention of the filmmakers. They are cajoling their non-verbal star and creating the performance through carefully crafted setups and edits, and it works.

Good Boy isn’t the first movie with “man’s best friend” as its lead (Lassie, Rin Tin Tin, Benji, etc.) nor is it the first movie asking us to think from a non-human perspective. Its familiarity is the point, and it asks us to think of the tried ghost story but from the perspective of the curious canine. The movie is probably as long as it can be at 70 minutes without feeling truly punishing or significantly complicating its world building. I can’t fault people for viewing Good Boy as more of a gimmick or experiment than a fully engaging movie. It’s not going to be for everyone by the nature of its limited perspective and development; not everyone is going to be captivated watching a dog react to things for an hour. It didn’t fascinate me like In a Violent Nature but it did make me rethink the familiar, and to that end it’s an overall success and confirmation that you should always trust the animals when they sense something hinky.

Good Boy isn’t the first movie with “man’s best friend” as its lead (Lassie, Rin Tin Tin, Benji, etc.) nor is it the first movie asking us to think from a non-human perspective. Its familiarity is the point, and it asks us to think of the tried ghost story but from the perspective of the curious canine. The movie is probably as long as it can be at 70 minutes without feeling truly punishing or significantly complicating its world building. I can’t fault people for viewing Good Boy as more of a gimmick or experiment than a fully engaging movie. It’s not going to be for everyone by the nature of its limited perspective and development; not everyone is going to be captivated watching a dog react to things for an hour. It didn’t fascinate me like In a Violent Nature but it did make me rethink the familiar, and to that end it’s an overall success and confirmation that you should always trust the animals when they sense something hinky.

Nate’s Grade: B-

The Amateur (2025)

I was genuinely surprised how much I enjoyed The Amateur, which on the surface seemed like a disposable revenge thriller. I never even realized it was a remake of a 1981 movie, co-starring Christopher Plummer. If you look closer, the screenplay has so many nifty little conflicts and points of interest to further draw you in. Rami Malek plays a CIA analyst whose wife dies in a terrorist attack who takes it upon himself to seek vengeance the old fashioned way: with his bare hands. He wants to become a field agent and get retribution, and he’s willing to blackmail his superiors in order to get the approval. From there we have the bosses trying to uncover the leverage against them, there’s a handler trying to train our protagonist but also keep him contained or supervised, and then there’s our would-be amateur who struggles with more physical hand-to-hand fighting and gunplay but can think on his feet and is a whiz with technology, especially improvised explosives. He’s taking out his hit list and going up the chain while his co-workers are trying to sabotage him. There’s so many fun cross-purposes of conflict that keeps the movie entertaining even when it follows a more formulaic “oh what price this vengeance” path. I appreciated that the main character has flaws and vulnerabilities. He’s not great at certain vital aspects to being a field agent, but his determination and adaptability overcome those shortcomings. It makes for a fairly entertaining underdog story with many possible antagonists targeting around our lead. A lot of the supporting characters are pretty rote and the general plot is fairly predictable but it’s the ongoing conflicts and challenges, plus the brain vs. brawn underdog perspective that allow The Amateur to be enjoyable popcorn thrills.

I was genuinely surprised how much I enjoyed The Amateur, which on the surface seemed like a disposable revenge thriller. I never even realized it was a remake of a 1981 movie, co-starring Christopher Plummer. If you look closer, the screenplay has so many nifty little conflicts and points of interest to further draw you in. Rami Malek plays a CIA analyst whose wife dies in a terrorist attack who takes it upon himself to seek vengeance the old fashioned way: with his bare hands. He wants to become a field agent and get retribution, and he’s willing to blackmail his superiors in order to get the approval. From there we have the bosses trying to uncover the leverage against them, there’s a handler trying to train our protagonist but also keep him contained or supervised, and then there’s our would-be amateur who struggles with more physical hand-to-hand fighting and gunplay but can think on his feet and is a whiz with technology, especially improvised explosives. He’s taking out his hit list and going up the chain while his co-workers are trying to sabotage him. There’s so many fun cross-purposes of conflict that keeps the movie entertaining even when it follows a more formulaic “oh what price this vengeance” path. I appreciated that the main character has flaws and vulnerabilities. He’s not great at certain vital aspects to being a field agent, but his determination and adaptability overcome those shortcomings. It makes for a fairly entertaining underdog story with many possible antagonists targeting around our lead. A lot of the supporting characters are pretty rote and the general plot is fairly predictable but it’s the ongoing conflicts and challenges, plus the brain vs. brawn underdog perspective that allow The Amateur to be enjoyable popcorn thrills.

Nate’s Grade: B

Elizabethtown (2005) [Review Re-View]

Originally released October 14, 2005:

Originally released October 14, 2005:

Cameron Crowe is a filmmaker I generally admire. He makes highly enjoyable fables about love conquering all, grand romantic gestures, and finding your voice. His track record speaks for itself: Say Anything, Singles, Jerry Maguire, Almost Famous (I forgive him the slipshod remake of Vanilla Sky, though it did have great artistry and a bitchin’ soundtrack). Crowe is a writer that can zero in on character with the precision of a surgeon. He’s a man that can turn simple formula (boy meets girl) and spin mountains of gold. With these possibly unfair expectations, I saw Elizabethtown while visiting my fiancé in New Haven, Connecticut. We made a mad dash to the theater to be there on time, which involved me ordering tickets over my cell phone. I was eager to see what Crowe had in store but was vastly disappointed with what Elizabethtown had to teach me.

Drew Baylor (Orlando Bloom) opens the film by narrating the difference between a failure and a fiasco. Unfortunately for him, he’s in the corporate cross-hairs for the latter. Drew is responsible for designing a shoe whose recall will cost his company an astounding “billion with a B” dollars (some research of an earlier cut of the film says the shoe whistled while you ran). His boss (Alec Baldwin) takes Drew aside to allow him to comprehend the force of such a loss. Drew returns to his apartment fully prepared to engineer his own suicide machine, which naturally falls apart in a great comedic beat. Interrupting his plans to follow career suicide with personal suicide is a phone call from his sister (Judy Greer). Turns out Drew’s father has died on a trip visiting family in Elizabethtown, Kentucky. Drew is sent on a mission from his mother (Susan Sarandon) to retrieve his father and impart the family’s wishes. On the flight to Kentucky, Drew gets his brain picked by Claire (Kirsten Dunst), a cheery flight attendant. While Drew is surrounded by his extended family and their down homsey charm and eccentricities, he seeks out some form of release and calls Claire. They talk for hours upon hours and form a fast friendship and stand on the cusp of maybe something special.

I think the most disappointing aspect of Elizabethtown for me is how it doesn’t have enough depth to it. Crowe definitely wears his heart on his sleeve but has never been clumsy about it. Elizabethtown wants to be folksy and cute and impart great lessons about love, life, and death. You can’t reach that plateau when you have characters walking around stating their inner feelings all the time, like Drew and Claire do. They might as well be wearing T-shirts that explain any intended subtext. Crowe squanders his film’s potential by stuffing too many storylines into one pot, thus leaving very little attachment to any character. Elizabethtown has some entertaining details, chiefly Chuck and Cindy’s drunk-on-love wedding, but the film as a whole feels too loose and disconnected to hit any emotional highs. If you want a better movie about self-reawakening, rent Garden State. If you want a better movie about dealing with loss, rent Moonlight Mile.

I think the most disappointing aspect of Elizabethtown for me is how it doesn’t have enough depth to it. Crowe definitely wears his heart on his sleeve but has never been clumsy about it. Elizabethtown wants to be folksy and cute and impart great lessons about love, life, and death. You can’t reach that plateau when you have characters walking around stating their inner feelings all the time, like Drew and Claire do. They might as well be wearing T-shirts that explain any intended subtext. Crowe squanders his film’s potential by stuffing too many storylines into one pot, thus leaving very little attachment to any character. Elizabethtown has some entertaining details, chiefly Chuck and Cindy’s drunk-on-love wedding, but the film as a whole feels too loose and disconnected to hit any emotional highs. If you want a better movie about self-reawakening, rent Garden State. If you want a better movie about dealing with loss, rent Moonlight Mile.

This is Bloom’s first test of acting that doesn’t involve a faux British accent and some kind of heavy weaponry. The results are not promising. Bloom is a pin-up come to life like a female version of Weird Science, a living mannequin, possibly an alien with great skin, but he isn’t a real compelling actor. He has about two emotions in his repertoire. His whiny American-ized accent seems to be playing a game of tag. He’s not a bad actor per se; he just gets the job done without leaving any sort of impression. To paraphrase Claire, he’s a “substitute leading man.”

Dunst is chirpy, kooky and cute-as-a-button but is better in small doses. Her accent is much more convincing than Bloom’s. Sarandon deserves pity for being involved in Elizabethtown‘s most improbable, cringe-worthy moment. At her husband’s wake, she turns her time of reflection into a talent show with a stand-up routine and then a horrifying tap dance. Apparently this gesture wins over the extended family who has hated her for decades. Greer (The Village) is utterly wasted in a role that approximates a cameo. Without a doubt, the funniest and most memorable performance is delivered by Baldwin, who perfectly mixes menace and amusement. He takes Drew on a tour of some of the consequences of the loss of a billion dollars, including the inevitable closing of his Wildlife Watchdog group. “We could have saved the planet,” Baldwin says in the most comically dry fashion. Baldwin nails the balance between discomfort and bewilderment.

Elizabethtown wants to be another of Crowe’s smart, feel-good sentimental field trips, but it falls well short. I was dumbfounded to see how little the story progressed. It lays the groundwork for a menagerie of subplots and then, in a rush to finish, caps everyone off with some emotionally unearned payoff. To put it simply, Elizabethtown wants credit and refuses to show its work. The film is packed with characters and ideas before succumbing into an interminable travelogue of America in its closing act, but what cripples Crowe’s film about opening up to emotional growth is that the movie itself doesn’t showcase growth. We see the rough and tumble beginnings of everyone, we see the hugs-all-around end, but we don’t witness that most critical movement that takes the audience from Point A to Point B. The results are beguiling and quite frustrating. Take the subplot about Drew’s cousin, who can?t connect to his father either and wants to be friends to his own son, a shrill little terror, instead of a father. Like most of Elizabethtown‘s storylines, these subplots die of neglect until a half-hearted nod to wrap everything up. Father sees son perform and all is well. Son does little to discipline child but all is well. Elizabethtown is sadly awash in undeveloped storylines and characters and unjustified emotions, and when they’re unjustified we go from sentiment (warm and fuzzy) to schmaltz (eye-rolling and false). I truly thought Crowe would know better than this.

Elizabethtown wants to be another of Crowe’s smart, feel-good sentimental field trips, but it falls well short. I was dumbfounded to see how little the story progressed. It lays the groundwork for a menagerie of subplots and then, in a rush to finish, caps everyone off with some emotionally unearned payoff. To put it simply, Elizabethtown wants credit and refuses to show its work. The film is packed with characters and ideas before succumbing into an interminable travelogue of America in its closing act, but what cripples Crowe’s film about opening up to emotional growth is that the movie itself doesn’t showcase growth. We see the rough and tumble beginnings of everyone, we see the hugs-all-around end, but we don’t witness that most critical movement that takes the audience from Point A to Point B. The results are beguiling and quite frustrating. Take the subplot about Drew’s cousin, who can?t connect to his father either and wants to be friends to his own son, a shrill little terror, instead of a father. Like most of Elizabethtown‘s storylines, these subplots die of neglect until a half-hearted nod to wrap everything up. Father sees son perform and all is well. Son does little to discipline child but all is well. Elizabethtown is sadly awash in undeveloped storylines and characters and unjustified emotions, and when they’re unjustified we go from sentiment (warm and fuzzy) to schmaltz (eye-rolling and false). I truly thought Crowe would know better than this.

Crowe has always been the defacto master of marrying music to film. Does anyone ever remember people singing Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” before its virtuoso appearance in 2000’s Almost Famous? Crowe has a nimble ear but his penchant for emotional catharsis set to song gets the better of him with Elizabethtown. There’s just way too many musical montages (10? 15?) covering the emotional ground caused by the script’s massive shortcomings. By the time a montage is followed by another montage, you may start growing an unhealthy ire for acoustic guitar. Because there are so many unproductive musical numbers and montages, especially when we hit the last formless act, Elizabethtown feels like Crowe is shooting the soundtrack instead of a story.

Elizabethtown is an under-cooked, unfocused travelogue set to music. Crowe intends his personal venture to belt one from the heart, but like most personal ventures the significance can rarely translate to a third party. It’s too personal a film to leave any lasting power, like a friend narrating his vacation slide show. Elizabethtown is gestating with plot lines that it can’t devote time to, even time to merely show the progression of relationships. The overload of musical montages makes the movie feels like the longest most somber music video ever. Bloom’s limited acting isn’t doing anyone any favors either. In the end, it all rings too phony and becomes too meandering to be entertaining. Elizabethtown is a journey the film won’t even let you ride along for. This movie isn’t an outright fiasco but given Crowe’s remarkable track record it can’t help but be anything but a failure.

Nate’s Grade: C

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I truly hope some day Cameron Crowe reads this. I owe him an apology.

I’ve always considered Elizabethtown the turning point in Crowe’s career, where things took an errant path that he’s been stuck on ever since, though there were certain warning signs with 2001’s Vanilla Sky. I was disappointed by this movie and the ensuing twenty years have only made me think back less favorably, since this was the juncture where Crowe’s hit-making streak of such tender, personal, and tremendously entertaining studio dramedies came to an end, where the Crowe projects afterwards felt more like Crowe was chasing after the idea of what makes a Cameron Crowe movie and losing his sense of self. I selected Elizabethtown for my 2025 re-watch mostly because I’ve never gone back to it in the proceeding two decades but also because it’s an important switch point in a popular artist’s career. What I wasn’t expecting when I re-watched the movie was to be so taken in by it considering my own personal circumstances.

This is a movie about grief, about putting one foot in front of the other, about coming to terms with mistakes and regrets, and ultimately looking ahead. It’s still a little corny, and it’s still got some flaws, but in 2025, having lost my own father not even a year ago as of this writing, Elizabethtown hit me square in the chest. It made me a mess of emotions and I could plug myself into this bittersweet yet gentle nudge of a film. Even the amiable tone and gentle, searching nature worked for me, as it felt like it was expertly channeling the fog of grief upon experiencing significant loss. Your body is sort of operating on autopilot and you feel outside yourself, like you’re watching a documentary about your life. You feel numb and recognize you’re in pain but you never really want to talk about it yet you crave human connectivity, and even when people awkwardly ask the question, “Are you doing okay?”, while the answer is obvious to all parties, you’re still unexpressively grateful for someone else granting the kindness of reaching out. This movie encapsulates this drifting feeling of loss and shock better than any I can recall. And in Crowe’s universe, which is like a more filled-in and colorful version of our own, strangers will take a moment to recognize your emotional pain and give you a hug. It’s a universe that cares about you, where even a guy getting married in your same hotel wants to invite you to his reception. There are no cynics in a Cameron Crowe universe, or at least if there are, they will be converted by the end like a Charles Dickens tale. It is a universe supremely about feeling and connectivity, and that’s what Drew (Orlando Bloom) has to learn.

This is a movie about grief, about putting one foot in front of the other, about coming to terms with mistakes and regrets, and ultimately looking ahead. It’s still a little corny, and it’s still got some flaws, but in 2025, having lost my own father not even a year ago as of this writing, Elizabethtown hit me square in the chest. It made me a mess of emotions and I could plug myself into this bittersweet yet gentle nudge of a film. Even the amiable tone and gentle, searching nature worked for me, as it felt like it was expertly channeling the fog of grief upon experiencing significant loss. Your body is sort of operating on autopilot and you feel outside yourself, like you’re watching a documentary about your life. You feel numb and recognize you’re in pain but you never really want to talk about it yet you crave human connectivity, and even when people awkwardly ask the question, “Are you doing okay?”, while the answer is obvious to all parties, you’re still unexpressively grateful for someone else granting the kindness of reaching out. This movie encapsulates this drifting feeling of loss and shock better than any I can recall. And in Crowe’s universe, which is like a more filled-in and colorful version of our own, strangers will take a moment to recognize your emotional pain and give you a hug. It’s a universe that cares about you, where even a guy getting married in your same hotel wants to invite you to his reception. There are no cynics in a Cameron Crowe universe, or at least if there are, they will be converted by the end like a Charles Dickens tale. It is a universe supremely about feeling and connectivity, and that’s what Drew (Orlando Bloom) has to learn.

Drew is under personal and professional crises. He’s been cast off at his job as an athletic shoe designer because his big design was recalled to the cost of a billion dollars. He says he’s begun cataloging “last looks” by co-workers, when people think this will be the last time they see him again. It’s a nice detail that comes back but also gets us thinking about the later drama with life and death, how every one of us will give our last looks to the people in our lives, we just won’t have the same sense of clarity. Drew is traveling to Kentucky to retrieve his father’s body and return home to his immediate family. This is intended to be a pit stop, a brief sojourn with extended family he doesn’t really see often, a respite before he gets his life back together. These significant loops in life become a natural reflective point, and that’s where Drew is coming from. His life has seemingly bottomed out, and the movie functions as his therapy session to process his grief and his shattered self-image. His sister, an undervalued Judy Greer, keeps asking if he’s had his “big cry” yet, and reminds him that it’s coming. By the end of the movie, it’s not Drew having come full-circle and found his way out of his grief fog. The whole movie is about just setting him up to actually address the loss and feel the completeness of his sadness. Under this perspective, the movie’s many menial supporting characters that dot the plot feel like gentle well-wishers. I complained about them in 2005 but in 2025 it makes the entire world feel like therapy accessories.

Much of the movie is also pinned on the romance between Drew and quirky flight attendant Claire (Kirsten Dunst), and it was her performance that coined the term Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG). She can definitely fit that mold but there’s a more subtle sadness to her that you see along the edges, like she’s putting so much effort into maintaining this front in public lest the mask drop and she has to deal properly with her own loneliness and disappointments. I think a more accurate depiction of the MPDG trope as a transparent sop to male fantasy is 2004’s Garden State with Natalie Portman’s spunky character. There is a sense that Claire’s off-screen long-distance bad boyfriend, Ben, is actually made up, an excuse to stop her from getting too close. She uses the term “tourist” to describe herself and Drew, and it’s fitting. The reality of her job makes her feel like she’s constantly in motion without setting down roots, prone to a thousand superficial human interactions that get washed from her memory as the day resets. It’s a transitory life and it can make a person feel outside of themself, questioning which version is their true self. The romantic dance between Claire and Drew really is all about both of them working up the nerve. It’s less a relationship that is fully formed and banging the drum of love; it’s far more an infatuation, where each side is circling over whether to risk the fun for something more. Under that guise, I’m more forgiving of the movie not exactly “showing its work” as I criticized in my original review. It’s not there because they aren’t there. This isn’t a relationship but a flirtation and friendship coalescing. It’s sweet and pleasant, like much of the movie, falling right in line with Crowe’s compassionate, humanist vibes.

Much of the movie is also pinned on the romance between Drew and quirky flight attendant Claire (Kirsten Dunst), and it was her performance that coined the term Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG). She can definitely fit that mold but there’s a more subtle sadness to her that you see along the edges, like she’s putting so much effort into maintaining this front in public lest the mask drop and she has to deal properly with her own loneliness and disappointments. I think a more accurate depiction of the MPDG trope as a transparent sop to male fantasy is 2004’s Garden State with Natalie Portman’s spunky character. There is a sense that Claire’s off-screen long-distance bad boyfriend, Ben, is actually made up, an excuse to stop her from getting too close. She uses the term “tourist” to describe herself and Drew, and it’s fitting. The reality of her job makes her feel like she’s constantly in motion without setting down roots, prone to a thousand superficial human interactions that get washed from her memory as the day resets. It’s a transitory life and it can make a person feel outside of themself, questioning which version is their true self. The romantic dance between Claire and Drew really is all about both of them working up the nerve. It’s less a relationship that is fully formed and banging the drum of love; it’s far more an infatuation, where each side is circling over whether to risk the fun for something more. Under that guise, I’m more forgiving of the movie not exactly “showing its work” as I criticized in my original review. It’s not there because they aren’t there. This isn’t a relationship but a flirtation and friendship coalescing. It’s sweet and pleasant, like much of the movie, falling right in line with Crowe’s compassionate, humanist vibes.

It’s hard to exactly quantify but Elizabethtown is more of its moments and the gradual pull that is tugging Drew toward his ultimate destiny, which amounts to self-acceptance and fully processing his grief. I originally castigated Drew’s mother (Susan Sarandon) trying out new hobbies as a means of busying herself in the wake of her husband’s demise, including turning the wake into a standup comedy audition. The jokes themselves can be a little cringey or in poor taste for a funeral, but the overall effort is about this woman trying to define her life now that her partner, the old sturdy definition, has departed. I see something similar with my own mother in the wake of my father’s death. I’m not expecting my mother to start making boner jokes like Sarandon, but I see how this identity crisis can become all-too familiar. I love the absolute chaos of the actual wake that erupts into a literal flaming bird while the family band jams out to Lyndard Skynard’s “Free Bird,” and as that famous guitar solo hits the stratosphere, the movie’s built-up pressure all seems to come to a head, and the continued playing of the song despite all the chaos is its own defiant act of catharsis. It unbounded something inside me as it does for the characters. Then there’s the extended conclusion where Drew drives all over with his father’s ashes and with Claire’s travel guide, notes, and curated soundtrack as companion. It’s a lot, but it’s also the final stretch that gets Drew to finally accept his feelings, to finally feel the totality of loss but also that totality of love, and while his father may be gone, that does not eliminate the lessons and love and memories that live within him. Having this personal deeper dive happen on a father-son road trip actually feels rather fitting and poignant even.

This is the third Cameron Crowe movie I’ve re-examined for my twenty-year re-reviews and it’s also my last. I never formally reviewed any of Crowe’s follow-up movies after 2005. I’ve already talked about how his career has taken a different track in other re-reviews, but I’ve come around on Elizabethtown, and that makes me wonder if maybe I’ll be more charitable to We Bought a Zoo or Aloha in time as well. In 2005, I found Elizabethtown to be a disappointing grab bag of Crowe’s touchy-feely familiarity, and now twenty years later, the movie really gelled for me. Perhaps I needed to go through a similar experience as the protagonist to be more open to its charms and artistic waves, or perhaps I’m getting nostalgic for Crowe’s kind of big-hearted romantic storytelling that hasn’t exactly been proliferating cinemas for some time. Perhaps I’ll watch Elizabethtown again years later and feel completely different, but I kind of doubt it, because now this movie is linked with my own reconciliation of grief after my father’s passing. It’s now been elevated from a disappointment from a revered filmmaker to something personal and passingly profound. It exemplified the foggy feelings and desire for connection for me post-funeral. As Claire says, “We are intrepid. We carry on.” Responding to failures and regrets should continue to resonate, and so Elizabethtown might actually become a personal movie I cherish over the years. It’s not the masterpiece that Almost Famous is, an all-timer, but hardly any other movies will rise to that level. I’ll accept Elizabethtown on its own terms in 2025, and those were the exact terms I needed to feel more whole.

This is the third Cameron Crowe movie I’ve re-examined for my twenty-year re-reviews and it’s also my last. I never formally reviewed any of Crowe’s follow-up movies after 2005. I’ve already talked about how his career has taken a different track in other re-reviews, but I’ve come around on Elizabethtown, and that makes me wonder if maybe I’ll be more charitable to We Bought a Zoo or Aloha in time as well. In 2005, I found Elizabethtown to be a disappointing grab bag of Crowe’s touchy-feely familiarity, and now twenty years later, the movie really gelled for me. Perhaps I needed to go through a similar experience as the protagonist to be more open to its charms and artistic waves, or perhaps I’m getting nostalgic for Crowe’s kind of big-hearted romantic storytelling that hasn’t exactly been proliferating cinemas for some time. Perhaps I’ll watch Elizabethtown again years later and feel completely different, but I kind of doubt it, because now this movie is linked with my own reconciliation of grief after my father’s passing. It’s now been elevated from a disappointment from a revered filmmaker to something personal and passingly profound. It exemplified the foggy feelings and desire for connection for me post-funeral. As Claire says, “We are intrepid. We carry on.” Responding to failures and regrets should continue to resonate, and so Elizabethtown might actually become a personal movie I cherish over the years. It’s not the masterpiece that Almost Famous is, an all-timer, but hardly any other movies will rise to that level. I’ll accept Elizabethtown on its own terms in 2025, and those were the exact terms I needed to feel more whole.

So thank you Cameron Crowe. It took twenty years but I’ve come around. This isn’t a folly, a failure, and certainly no fiasco. It’s actually a sweet and moving tale about trying to find your direction in the face of grief and shame and just finding your way out the other side of the fog. For me, this whole movie was about the universe working through a million cheerful helpers to nudge Drew back onto his feet, including our love interest, which seems less damnable if the entire movie is achieving the same results. For a person looking through tragedy and asking why, it’s just enough encouragement, wisdom, and empathy to feel nourishing without feeling overwhelming, and it doesn’t feel phony at all to me in 2025.

Elizabethtown was what I needed. I love you dad and miss you every day.

Lilo & Stitch (2025)/ How to Train Your Dragon (2025)

Two new live-action remakes are recreating Millennial staples, Lilo & Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon, as transparent facsimiles, and they’re both reasonably fine. If you’ve never watched either animated movie, you’d maybe even call the live-action versions pretty good for your first experiences with these stories. Both movies understand what works essentially from their predecessors and don’t reinvent the wheel. They keep things pretty safe and strict, which translates into pleasant but predictable entertainment for anyone familiar with the originals.

Two new live-action remakes are recreating Millennial staples, Lilo & Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon, as transparent facsimiles, and they’re both reasonably fine. If you’ve never watched either animated movie, you’d maybe even call the live-action versions pretty good for your first experiences with these stories. Both movies understand what works essentially from their predecessors and don’t reinvent the wheel. They keep things pretty safe and strict, which translates into pleasant but predictable entertainment for anyone familiar with the originals.

I don’t even know how to fully review these entries, which is why I’m combining them together. They’re both so thoroughly fine yet one is the highest-grossing movie of 2025 so far, the popularity of which I cannot explain. My conceptual issue with the nature of live-action remakes is the implicit belief that animated films improve when they are brought into a real-world setting. I strongly disagree. Animated movies can be vibrant, stylistic, and exaggerated in such daring and artistically enigmatic ways. Translating that into real-life often strips away that style or liveliness; take for instance how un-expressive and dour the “live-action” Lion King was, a collection of possessed (cursed?) taxidermy. Animation does not require verisimilitude to be entertaining or engaging. I’m also worried over the speed of which these live-action remakes are coming, now refreshing fairly recent movies. Has there been enough distance between now and 2010 to have compelling artistic differences with the original How to Train Your Dragon? Apparently not. When the live-action Moana comes out in 2026, will it be dramatically different or better than the animated version? I strongly doubt it. We need more distance from the original animated movies so the remakes aren’t just slavish yet inferior versions of the originals. There needs to be more than simply a tracing over. I don’t see this ending any time soon considering the commercial rewards, and so the live-action Lilo & Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon continue to be good stories, just unnecessary.

I don’t even know how to fully review these entries, which is why I’m combining them together. They’re both so thoroughly fine yet one is the highest-grossing movie of 2025 so far, the popularity of which I cannot explain. My conceptual issue with the nature of live-action remakes is the implicit belief that animated films improve when they are brought into a real-world setting. I strongly disagree. Animated movies can be vibrant, stylistic, and exaggerated in such daring and artistically enigmatic ways. Translating that into real-life often strips away that style or liveliness; take for instance how un-expressive and dour the “live-action” Lion King was, a collection of possessed (cursed?) taxidermy. Animation does not require verisimilitude to be entertaining or engaging. I’m also worried over the speed of which these live-action remakes are coming, now refreshing fairly recent movies. Has there been enough distance between now and 2010 to have compelling artistic differences with the original How to Train Your Dragon? Apparently not. When the live-action Moana comes out in 2026, will it be dramatically different or better than the animated version? I strongly doubt it. We need more distance from the original animated movies so the remakes aren’t just slavish yet inferior versions of the originals. There needs to be more than simply a tracing over. I don’t see this ending any time soon considering the commercial rewards, and so the live-action Lilo & Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon continue to be good stories, just unnecessary.

Nate’s Grades: B

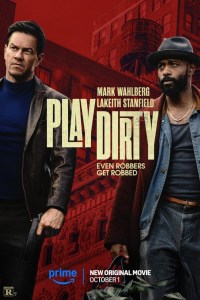

Play Dirty (2025)

Shane Black is one of the best known writers in Hollywood across three-plus decades. His brand of witty, self-referential genre writing became its own appealing sub-genre of action cinema from the 1980s into the 90s. He resurrected Robert Downey Jr.’s career with Black’s directorial debut, the rollicking and immensely entertaining Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Downey returned the favor by getting Black the gig writing and directing Iron Man 3. It’s been eight years since Black’s last directing effort, 2018’s messy and ultimately disappointing Predator reboot (Black actually had a small acting role in the original film). Shane Black movies are never ever boring even when they’re not completely working. Play Dirty is based on the Parker book series, a character portrayed by six other actors including Mel Gibson, Jason Statham, and Jim Brown. There are 26 of these Parker books, but after watching Play Dirty, by far Black’s worst movie, I don’t even understand what the appeal would be. This character just plain sucks.

Shane Black is one of the best known writers in Hollywood across three-plus decades. His brand of witty, self-referential genre writing became its own appealing sub-genre of action cinema from the 1980s into the 90s. He resurrected Robert Downey Jr.’s career with Black’s directorial debut, the rollicking and immensely entertaining Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Downey returned the favor by getting Black the gig writing and directing Iron Man 3. It’s been eight years since Black’s last directing effort, 2018’s messy and ultimately disappointing Predator reboot (Black actually had a small acting role in the original film). Shane Black movies are never ever boring even when they’re not completely working. Play Dirty is based on the Parker book series, a character portrayed by six other actors including Mel Gibson, Jason Statham, and Jim Brown. There are 26 of these Parker books, but after watching Play Dirty, by far Black’s worst movie, I don’t even understand what the appeal would be. This character just plain sucks.

Parker (Mark Wahlberg) is a slick professional criminal trying to score big and get his revenge. In the opening sequence, one of his heist crew, Zen (Rosa Salazar), betrays the group, steals the money, and kills everybody except Parker. He tracks her down and she’s in the middle of an even bigger scheme, one involving billions of dollars from uncovering literal sunken treasure on the ocean floor. He doesn’t like her or trust her but he sure could use his cut of a billion dollars. He taps old colleagues from other old jobs, the colleagues who haven’t been killed, and they must all work together to get their next big score.

I was blown away by how powerfully unlikable the main character comes across. I don’t need characters to all be beholden to my opinion of likeability, but deficits in this matter are typically offset by writing the character with some degree of personality, menace, or intrigue, something that makes you want to keep watching them onscreen even if you don’t agree with everything they’re doing. However, this Parker guy, as portrayed by Wahlberg, is a big dumb guy who doesn’t recognize he’s a big dumb guy. As a result, he’s beholden to impulsive decisions that come across as cruel to the point of being sociopathic. Again, we’re used to criminal characters being flippant or prone to violence in other stories, but the introductory presentation of this character simply befuddles me and rubbed me the wrong way throughout.

I was blown away by how powerfully unlikable the main character comes across. I don’t need characters to all be beholden to my opinion of likeability, but deficits in this matter are typically offset by writing the character with some degree of personality, menace, or intrigue, something that makes you want to keep watching them onscreen even if you don’t agree with everything they’re doing. However, this Parker guy, as portrayed by Wahlberg, is a big dumb guy who doesn’t recognize he’s a big dumb guy. As a result, he’s beholden to impulsive decisions that come across as cruel to the point of being sociopathic. Again, we’re used to criminal characters being flippant or prone to violence in other stories, but the introductory presentation of this character simply befuddles me and rubbed me the wrong way throughout.

Take for instance the literal opening minutes of Play Dirty. It’s in the middle of a heist but the story doesn’t start us off with the perspective of our thieves collecting their loot. It starts instead with a security guard stumbling onto their heist. He’s with his wife and child in the car and decides, rather than intervening, he’s going to use this opportunity to steal himself some of their ill-gotten loot. Right there, we’re starting with a character making a consequential choice, and our perspectives are not aligned with the robbers but with the robber of the robbers. I wanted him to get away, and frankly, following his story could have proven compelling as well, as someone who gets in over their head and tracked down by professional criminals who want what was taken. Parker gives chase through a race track and eventually shoots this man dead in front of his wife and child. Lest you think Parker is an irredeemable, unfeeling cretin, he takes stock of this woman’s grief and trauma and offers her ten thousand dollars of their loot, to bribe her silence and make amends for the murder of her spouse (that’s not even a good life insurance payout). I don’t know why Black wanted us to begin empathizing from the perspective of some guy who was only intended to be unceremoniously killed, in front of his wife and child. This move made me immediately dislike Parker, and then his little gift for the wife’s trauma felt completely insulting.

This incident isn’t the only example of Parker being a shoot-first-ask-questions-never brute of limited intelligence. When he reunites with Zen, she’s talking with some guy who planned her new big scheme. Parker doesn’t know anything about this guy other than his physical proximity to Zen. He shoots him dead. For what reason? I don’t know what he was trying to accomplish except an expression of his impatience and hatred for life. I wonder if an elderly nun had been standing next to Zen at this moment and would Parker have committed the same rash act of violence. What about if it was his own mother? To make matters even worse, Parker accompanies Zen to break the news to the dead man’s boyfriend, and it’s in this moment of shock and grief that Parker harasses this bereaved man that Parker berates for crying. He seems to take amusement in how bluntly he informs the other man that his love is never coming back, though leaving out the key part where he carelessly murdered the man. He also shoots Mark Cuban in the leg while he dines in a restaurant for no reason other than being near the guy that he wanted. Again, much of this could be workable if the character of Parker was… anything. He’s not funny, he’s not charming, he’s not really clever or good with plans; he’s just a big dumb guy prone to violence, scowling, and deep sighs. Wahlberg looks bored throughout the whole movie and it makes the character even harder to entertain. If this guy doesn’t want to be here, can we select someone else to be our requisite protagonist?

This incident isn’t the only example of Parker being a shoot-first-ask-questions-never brute of limited intelligence. When he reunites with Zen, she’s talking with some guy who planned her new big scheme. Parker doesn’t know anything about this guy other than his physical proximity to Zen. He shoots him dead. For what reason? I don’t know what he was trying to accomplish except an expression of his impatience and hatred for life. I wonder if an elderly nun had been standing next to Zen at this moment and would Parker have committed the same rash act of violence. What about if it was his own mother? To make matters even worse, Parker accompanies Zen to break the news to the dead man’s boyfriend, and it’s in this moment of shock and grief that Parker harasses this bereaved man that Parker berates for crying. He seems to take amusement in how bluntly he informs the other man that his love is never coming back, though leaving out the key part where he carelessly murdered the man. He also shoots Mark Cuban in the leg while he dines in a restaurant for no reason other than being near the guy that he wanted. Again, much of this could be workable if the character of Parker was… anything. He’s not funny, he’s not charming, he’s not really clever or good with plans; he’s just a big dumb guy prone to violence, scowling, and deep sighs. Wahlberg looks bored throughout the whole movie and it makes the character even harder to entertain. If this guy doesn’t want to be here, can we select someone else to be our requisite protagonist?

We might have a leaden dud of a lead, but what about the rest of our enterprising team of thieves and conmen? Do we have any winners here to compensate? Sadly, the team is just as listless. Take Grofield (Lakieth Stanfield) who fraternizes as a theater owner, one who is constantly losing money. That setup has some interest, a criminal who possibly longs to be more of a professional actor, perhaps that eagerness even pushes him into suggesting different covers and roles he could play in their heists. Perhaps he might even see himself above the others since he feels like he is trying to promote the arts. There’s all kinds of ways this introduction could better shape his personality, interests, and contrasts with the other crew. For the rest of the movie, Grofield is just another guy on screen, just another guy driving a car or shooting a gun. There is one brief moment that takes advantage of his interest in acting as he poses as a drunk on a rooftop threatening to jump. After a security guard arrives on the scene, he and Parker subdue the guard, coat him in the same outfit Grofield was wearing, and then toss him off the roof to his death (ho ho). There’s a husband and wife team of crooks (Keegan-Michael Key, Claire Lovering) and that could be interesting, especially if they’re mixing professional and romantic squabbles, or maybe working together is the thing that keeps their spark going, the showcase for their real teamwork. They have one scene with some passing bickering but otherwise they too are just more indiscriminate people onscreen, another person to hold a gun or drive a car. Even the bad guys are boring. Who should I actually care about? I was rooting for that grieving mother and the one guy’s sad boyfriend to team up and punish Parker’s crew.

Part of the fun of heist crews and con artists are the colorful personalities, the peculiarities, the intra-group conflicts and dynamics, but this movie gives us so little. It’s almost as if the characters are merely meant to trick the brain of a viewer barely paying attention, providing an assurance, “These are the guys,” without forcing thinking over differentiation. It’s like the film equivalent of not wanting to arouse like your elderly grandfather with conflicting evidence contrary to his memories. It’s like accepting defeat.

Part of the fun of heist crews and con artists are the colorful personalities, the peculiarities, the intra-group conflicts and dynamics, but this movie gives us so little. It’s almost as if the characters are merely meant to trick the brain of a viewer barely paying attention, providing an assurance, “These are the guys,” without forcing thinking over differentiation. It’s like the film equivalent of not wanting to arouse like your elderly grandfather with conflicting evidence contrary to his memories. It’s like accepting defeat.

So the characters are lousy, are there any outstanding or fun caper or action scenes? Black is known for his snappy style and pulpy sensibilities across genres. He hasn’t made a boring movie yet, so I had hoped that even if Play Dirty ultimately proved lackluster, at least it would provide some flash and fun. Nope. Many of the action scenes are Parker and company just throwing caution to the wind and shooting a bunch of guys. There’s one sequence in the middle that involves actually planning and steps to draw our interest, it’s a ridiculously over-the-top plan that shows once again the crew’s disregard for collateral damage. Their valuable cargo is being shipped through the city on an elevated train, so the team decides to derail the train in the middle of the city. Not in a deserted area unpopulated by civilians, in the middle of town. As expected, the train careens off the tracks and through the city, likely causing the deaths of dozens of innocents we’ll never know because their existence is unworthy of the movie’s attention, much like the suffering of that widow and child in the opening sequence. The sequence is the equivalent of killing a mosquito with a flamethrower, and while overkill can certainly be cinematic and pleasingly entertaining, just ask Michael Bay or James Wan, it needs to exist in a world where that overkill is normalized. Otherwise, it just stands out as excessive and causes us to poke holes at the baseline reality.

Play Dirty is astoundingly dull and witless, lacking any of the spark and personality flair I expect from a Shane Black vehicle. Mark Wahlberg’s somnambulist performance is the best symbol for this entire enterprise, a crime thriller going through the motions but with its mind elsewhere. I know I certainly felt my mind going elsewhere while watching. Not just dull and tedious, Play Dirty is also just an uncomfortable experience because we’re stuck watching a group of unrepentantly amoral characters endanger and kill innocent lives in the pursuit of ill-gotten gains, but these characters aren’t intriguing, complex, memorable, or even cool, so the whole movies feels like you’re watching a pack of dude bros just randomly terrorize anecdotal characters out of sheer detached boredom and nihilism. It’s not fun, it’s actually quite the opposite of fun, and I wish Black had put more of himself into this enterprise (hey, the Christmas setting is present). Who wants to play with characters this boring and repulsive for two hours?

Nate’s Grade: C-

You must be logged in to post a comment.