Blog Archives

Garden State (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

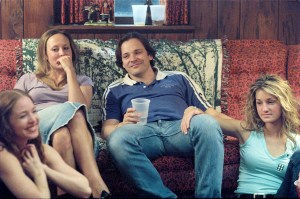

Andrew Large Largeman (Braff) is an out-of-work actor living in an anti-depressant haze in LA. He heads back to his old stomping grounds in New Jersey when he learns that his mother has recently died. Andrew has to reface his psychiatrist father (Ian Holm), the source of his guilt and prescribed numbness. He has forgotten his lithium for his trip, and the consequences allow Andrew to begin to awaken as a human being once more. He meets old friends, including Mark (Peter Sarsgaard), who now digs graves for a living and robs them when he can. He parties at the mansion of a friend made rich by the invention of silent Velcro. Things really get moving when Andrew meets Sam (Natalie Portman), a free spirit who has trouble telling the truth and staying still. Their budding relationship coalesces with Andrews re-connection to friends, family, and the joys life can offer.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff deserves a medal for finally coaxing out the actress in Portman. She herself has looked like an overly medicated, numb being in several of her recent films (Star Wars prequels, I’m looking in your direction), but with her plucky, whimsical role in Garden State, Portman proves that her careers acting apex wasn’t in 1994’s The Professional when she was 12. Her winsome performance gives Garden State its spark, and the sincere romance between Sam and Andrew gives it its heart.

Sarsgaard is fast becoming one of the best young character actors out there. After solid efforts in Boys Don’t Cry and Shattered Glass, he shines as a coarse but affectionate grave robber that serves as Andrew’s motivational elbow-in-the-ribs. Only the great Holm seems to disappoint with a rare stilted and vacant performance. This can be mostly blamed on Braff’s underdevelopment of the father role. Even Method Man pops up in a very amusing cameo.

The humor in Garden State truly blossoms. There are several outrageous moments and wonderfully peculiar characters, but their interaction and friction are what provide the biggest laughs. So while Braff may shoehorn in a frisky seeing-eye canine, a knight of the breakfast table, and a keeper of an ark, the audience gets its real chuckles from the characters and not the bizarre scenarios. Garden State has several wonderfully hilarious moments, and its sharp sense of humor directly attributes to its high entertainment value. The film also has some insightful looks at family life, guilt, romance, human connection, and acceptance. Garden State can cut close like a surgeon but it’s the surprisingly elegant tenderness that will resonate most with a crowd.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Garden State is not a flawless first entry for Braff. It really is more a string of amusing anecdotes than an actual plot. The film’s aloof charm seems to be intended to cover over the cracks in its narrative. Braff’s film never ceases to be amusing, and it does have a warm likeability to it; nevertheless, it also loses some of its visual and emotional insights by the second half. Braff spends too much time on less essential moments, like the all-day trip by Mark that ends in a heavy-handed metaphor with an abyss. The emotional confrontation between father and son feels more like a baby step than a climax. Braff’s characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.

Garden State is a movie thats richly comic, sweetly post-adolescent, and defiantly different. Braff reveals himself to be a talent both behind the camera and in front of it, and possesses an every-man quality of humility, observation, and warmth that could soon shoot him to Hollywood’s A-list. His film will speak to many, and its message about experiencing lifes pleasures and pains, as long as you are experiencing life, is uplifting enough that you may leave the theater floating on air. Garden State is a breezy, heartwarming look at New York’s armpit and the spirited inhabitants that call it home. Braff delivers a blast of fresh air during the summer blahs.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

In the summer of 2024, there were two indie movies that defined the next years of your existence. If you were under 18, it was Napoleon Dynamite. If you were between 18 and 30, it was Garden State. Zack Braff’s debut as writer/director became a Millennial staple on DVD shelves, and I think at one time it might have been the law that everyone had to own the popular Grammy-winning soundtrack. It wasn’t just an indie hit, earning $35 million on a minimal budget of $2.5 million; it was a Real Big Deal, with big-hearted young people finding solace in its tale of self-discovery and shaking loose from jaded emotional malaise. If you had to determine a list of the most vital Millennial films, not necessarily on quality but on popularity and connection to the zeitgeist, then Garden State must be included. Twenty years later, it’s another artifact of its time, hard to fully square outside of that influential period. It’s a coming-of-age tale wrapped up in about every quirky indie trope of its era, including a chief example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, even though that term was first coined from the AV Club review of 2005’s Elizabethtown. Twenty years later, Garden State still has some warm fuzzies but loses its feels.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Natalie Portman had been an actress that I was more cool over until 2004 with the double-whammy of Garden State and her Oscar-nominated turn in Closer. She’s since become one of the most exciting actors who goes for broke in her performances whether they might work or not. In 2004, I thought her performance in Garden State was an awakening for her, and in 2024 it now feels so starkly pastiche. Bless her heart, but Portman is just calibrated for the wrong kind of movie. Her energy level is two to three times that of the rest of the movie, and while you can say she’s the spark plug of the film, the jolt meant to shake Andrew awake, her character comes across more as an overwritten cry for help. Sam is even more prototypical Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) than Kirsten Dunst’s bouncy character in Elizabethtown. Her entire existence is meant to provoke change upon our male character. This in itself is not an unreasonable fault; many characters in numerous stories are meant to represent a character’s emotional state. It’s just that there isn’t much to Sam besides a grab-bag of quirky characteristics: she’s a compulsive liar, though nothing is ever really done with this being a challenge to building lasting bonds; she’s incapable of keeping pets alive, and Andrew could be just another pet; she’s consumed with being unique to the point of having to stand up and blurt out nonsense words to convince herself that nobody in human history has duplicated her recent combination of sounds and body gestures, but she’s all archetype. She exists to push Andrew along on his reawakening, including introducing him and us to The Shins (“This song will change your life”). She’s entertaining, and Portman is charming, but it’s an example of trying so hard. I thought her cheeks must have hurt from holding a smile so long. I’m sure Braff would compare Sam to Annie Hall, as Diane Keaton was perhaps the mold for the MPDG, except she more than stood on her own and didn’t need a nebbish man to complete her.

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

Admittedly, that soundtrack is still a banger. It soars when it needs to, like Imogen Heep’s “Let Go” over the race-back-to-the-girl finale, and it’s deftly somber when it needs to, like Iron and Wine’s cover of “Such Great Heights” and “The Only Living Boy in New York” paired with our big movie kiss. It’s such a cohesive, thematic whole that lathers over the exposed seams of the movie’s scenic hodgepodge. Braff tried to find similar magic with his musical choices for 2006’s The Last Kiss, a movie he starred in but did not direct (he also provided un-credited rewrites to Paul Haggis’ adapted screenplay). That soundtrack is likewise packed with eclectic artists (he even snags Aimee Mann) but failed to resonate like Garden State. It’s probably because nobody saw the movie and Braff’s character was, as I described in my 2006 review, an overgrown man-child afraid his life lacks “surprises” now that he was going to be a father. Sheesh.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Re-View Grade: C+

Going in Style (2017)

If seeing Michael Caine, Morgan Freeman, and Alan Arkin pal around and bicker for 90 minutes is enough reason to see a movie, then Going in Style offers that and precious little else. This is a movie that offers little more than three great old codgers doing their schtick as they plan to rob the bank that is cheating them out of their hard-earned pensions. The old-guys-acting-up routines vary from mildly amusing to sad and desperate, like a sequence where the trio inexplicably decide to practice their criminal impulses by robbing a convenience store. It’s all so broad and obvious and lackluster. There’s a scene where they get high and the mere utterance of the word “munchies” seems like it’s intended to be a comedic payoff. Going in Style is a remake of a 1979 movie where George Burns, Art Carney, and Lee Strasberg take to a life of crime to animate them from a forgotten existence. It was strangely serious and had pockets of depth about the kind of care the elderly were receiving and how invisible their needs became to our country. This update loses any seriousness for exasperated and hollow hijinks. One-time indie darling Zach Braff (Garden State) takes his turn as a hired gun directing for the studio system. I don’t know if he was easily cowed by the acting veterans or the studio, but his comedy instincts honed over several seasons from Scrubs feel muted here. My theater was packed with people old enough to get their social security checks and they were barely chuckling politely. It’s predictable every step of the way and ginned up with contrived conflicts. Still, if all you want to see is a group of octogenarians crack wise and act foolish and you have no other pressing demands, Going in Style may be just enough to get by.

If seeing Michael Caine, Morgan Freeman, and Alan Arkin pal around and bicker for 90 minutes is enough reason to see a movie, then Going in Style offers that and precious little else. This is a movie that offers little more than three great old codgers doing their schtick as they plan to rob the bank that is cheating them out of their hard-earned pensions. The old-guys-acting-up routines vary from mildly amusing to sad and desperate, like a sequence where the trio inexplicably decide to practice their criminal impulses by robbing a convenience store. It’s all so broad and obvious and lackluster. There’s a scene where they get high and the mere utterance of the word “munchies” seems like it’s intended to be a comedic payoff. Going in Style is a remake of a 1979 movie where George Burns, Art Carney, and Lee Strasberg take to a life of crime to animate them from a forgotten existence. It was strangely serious and had pockets of depth about the kind of care the elderly were receiving and how invisible their needs became to our country. This update loses any seriousness for exasperated and hollow hijinks. One-time indie darling Zach Braff (Garden State) takes his turn as a hired gun directing for the studio system. I don’t know if he was easily cowed by the acting veterans or the studio, but his comedy instincts honed over several seasons from Scrubs feel muted here. My theater was packed with people old enough to get their social security checks and they were barely chuckling politely. It’s predictable every step of the way and ginned up with contrived conflicts. Still, if all you want to see is a group of octogenarians crack wise and act foolish and you have no other pressing demands, Going in Style may be just enough to get by.

Nate’s Grade: C

Oz the Great and Powerful (2013)

Usually when I’m watching a bad movie I have to stop and think where did things go so wrong, where did the wheels fall off, what choice lead to the disaster I am watching play out onscreen. In the case of Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful, a Wizard of Oz prequel that pretty much hovers over the cusp of bad for its entire 130 minutes, I have to stop and think, “How could this movie ever have gone right?” I don’t think it could have, at least not with this script, this cast, and the edict from the Mouse House to keep things safe and homogenized, smothered in CGI gumbo and scrubbed clean of any real sense of venerable movie magic.

Usually when I’m watching a bad movie I have to stop and think where did things go so wrong, where did the wheels fall off, what choice lead to the disaster I am watching play out onscreen. In the case of Disney’s Oz the Great and Powerful, a Wizard of Oz prequel that pretty much hovers over the cusp of bad for its entire 130 minutes, I have to stop and think, “How could this movie ever have gone right?” I don’t think it could have, at least not with this script, this cast, and the edict from the Mouse House to keep things safe and homogenized, smothered in CGI gumbo and scrubbed clean of any real sense of venerable movie magic.

In 1905 Kansas, the magician Oz (James Franco) is used to bilking country folk out of their meager earnings. He’s a con man and runs afoul with a strong man in his own traveling circus. He makes a hasty escape in a hot air balloon and, thanks to a coincidental tornado, is whisked away to the Land of Oz. The people have long been told that a wizard would come and rescue them from the tyranny of the wicked witch. Theodora (Mila Kunis) and Evanora (Rachel Weisz), sisters controlling the Emerald City, task Oz with killing the other witch, Glinda (Michelle Williams). If he succeeds, Oz will become king and riches will be his. Along his journey he collects a band of cuddly sidekicks (flying monkey, China doll, munchkin) and learns that he may indeed be the hero that Oz needs to save the day.

Oz the Great and Powerful is really just 2010’s Alice in Wonderland slapped together with a fresh coat of paint and some extra dwarves. I say this because, like Alice, this movie suffers from a plot that feebly sticks to the most generic of all fantasy storylines – the Great prophecy speaks about a Great savior who will save us from the Great evil. Naturally, the so-called chosen one has internal doubts about the burden they face, initially ducking out before finding that inner strength they had all long to prove they were indeed the one prophesized. It even got to the point where I was noticing some of the same plot beats between the two movies, like how last in the second act we spend time with a woman dressed all in white who we’ve been told is the villain but who is really the good guy. Then there’s the now-routine rounding up of magical creatures to combat the evil hordes in a big battle. Considering Alice was billion-dollar hit for Disney, it’s no surprise they would try and apply its formula to another magical universe hoping for the same results. Well I thought Alice was weak but Oz is even weaker. However, at least nobody absurdly starts breakdancing by the end. Small victories, people.

Oz the Great and Powerful is really just 2010’s Alice in Wonderland slapped together with a fresh coat of paint and some extra dwarves. I say this because, like Alice, this movie suffers from a plot that feebly sticks to the most generic of all fantasy storylines – the Great prophecy speaks about a Great savior who will save us from the Great evil. Naturally, the so-called chosen one has internal doubts about the burden they face, initially ducking out before finding that inner strength they had all long to prove they were indeed the one prophesized. It even got to the point where I was noticing some of the same plot beats between the two movies, like how last in the second act we spend time with a woman dressed all in white who we’ve been told is the villain but who is really the good guy. Then there’s the now-routine rounding up of magical creatures to combat the evil hordes in a big battle. Considering Alice was billion-dollar hit for Disney, it’s no surprise they would try and apply its formula to another magical universe hoping for the same results. Well I thought Alice was weak but Oz is even weaker. However, at least nobody absurdly starts breakdancing by the end. Small victories, people.

Beyond the formula that dictates the plot, the characters are poorly developed and broach some off-putting gender stereotypes. The character of Oz is portrayed as a scoundrel who eventually learns to be selfless, but I never really bought the major turning points for his character arc. Do all major characters need to be flawed men in need of redemption in magical worlds? I understand what they were doing with his character but I don’t think it ever worked, and certainly Franco’s performance is at fault as well (more on that later). The ladies of Oz, however, just about constitute every female stereotype we can expect in traditional movies. One of them is conniving but given no reason for why this is. One of them is pure and motherly. And then one of them gets lovesick so easily, falling head over heels for a boy in a matter of hours that she’s willing to throw her life away in spite. And all of these witches, who can actually perform magic unlike the charlatan Oz, sure seem like they don’t need a man to run the kingdom for them and tell them what to do. It’s sad that a conflict that involves feudal power grabs should devolve into a misconstrued love triangle. Then there’s the role of the little China Girl (voiced by Joey King) who adds absolutely nothing to the story except as another female in need of assistance and doting, except when she inexplicably behaves like a surly teenager in a tone-breaking head-turning moment. Oz keeps resting the very breakable doll on his shoulder, like a parrot. I suppose it’s better than tucking her in his pants.

The movie is also tonally all over the place. It wants to be scary but not too scary. Personally, I always found the talking trees to be spookier than the flying monkeys but that’s my own cross to bear. It wants to be funny but often stoops to lame slapstick and Zach Braff (Garden State) as a goofy flying monkey sidekick. It wants to be exciting but it never takes a step beyond initial menace. Its big climactic battle is more like a children’s version of something you’d see in the Lord of the Rings. The movie fails to satisfyingly congeal and so every set piece feels like it could be from a different movie.

Some notable casting misfires also serve to doom the project. I like Franco (Rise of the Planet of the Apes) as an actor, I do, but he is grossly miscast here. He does not have the innate charm to pull off a huckster like Oz. Franco usually has an off kilter vibe to him, one that’s even present in this film, that gives him a certain mysterious draw, but he does not work as an overblown man of theatricality. Combined with lackluster character, it makes for one very bland performance that everyone keeps marveling over. It’s like all the supporting characters, in their fawning praise, are meant to subconsciously convince you that Franco is actually succeeding. Kunis (Friends with Benefits) is also a victim of bad casting. She can do the innocent ingénue stuff but when she (spoiler alert) turns mean and green it just does not work. When she goes bad she looks like Shrek’s daughter and she sounds like a pissy version of her character from Family Guy, which is ineffectual to begin with. Kunis cannot believably portray maniacal evil; sultry evil, a corrupting influence like in Black Swan, most definitely, but not this. There are lines where she screeches at the top of her lungs and it just made me snicker (“CUUUUUURSE YOOOOOOU!”).

Some notable casting misfires also serve to doom the project. I like Franco (Rise of the Planet of the Apes) as an actor, I do, but he is grossly miscast here. He does not have the innate charm to pull off a huckster like Oz. Franco usually has an off kilter vibe to him, one that’s even present in this film, that gives him a certain mysterious draw, but he does not work as an overblown man of theatricality. Combined with lackluster character, it makes for one very bland performance that everyone keeps marveling over. It’s like all the supporting characters, in their fawning praise, are meant to subconsciously convince you that Franco is actually succeeding. Kunis (Friends with Benefits) is also a victim of bad casting. She can do the innocent ingénue stuff but when she (spoiler alert) turns mean and green it just does not work. When she goes bad she looks like Shrek’s daughter and she sounds like a pissy version of her character from Family Guy, which is ineffectual to begin with. Kunis cannot believably portray maniacal evil; sultry evil, a corrupting influence like in Black Swan, most definitely, but not this. There are lines where she screeches at the top of her lungs and it just made me snicker (“CUUUUUURSE YOOOOOOU!”).

I had faith that a director as imaginative as Sam Raimi (Spider-Man, Drag Me to Hell) would be a stolid shepherd for a fantasy-rich project such as Oz. I never got any sense of Raimi in this movie. It felt like he too was smothered completely by the overabundance of special effects. It’s a common complaint that modern movies are buried under an avalanche of soulless computer effects, but usually I find this bromide to be overstated. Having seen Oz, I can think of no more accurate description than “soulless computer effects overload.” At no point in the movie does any special effect come close to feeling real. At no point do you feel immersed in this world, awed by its unique landscapes and inhabitants (it feels often more like the land of Dr. Seuss than Oz). I chose to see the film in good ole standard 2D, though the 3D eye-popping elements are always quite noticeable. At no point do you feel any sense of magic, the most damming charge of all considering the legacy of Oz. The original Wizard of Oz holds a special place in many a heart. We recall feeling that sense of wonder and magic when we watched it as a child, the idea that movies could be limitless and transporting. While watching Raimi’s trip to Oz, I only felt an overwhelming sense of apathy that grew disquieting.

Then there’s the matter of the questionable messages that the movie posits. It celebrates the power of belief, which is admirable, but it’s belief in a lie. Oz is a fake, yet the movie wants to say that faith in false idols is something worth celebrating. Oz and his cohorts put together a deception to fool the denizens of the world into a false sense of security. Everyone believes in the Wizard of Oz so he has power but it’s all a sham. We’re supposed to feel good that these people have been fooled. Didn’t The Dark Knight Rises basically showcase what ultimately happens when a society’s safety is based around a lie and false idols? I understand that as a prequel one of its duties is to set up things for when Dorothy comes knocking, but do I have to be force-fed disingenuous moral messages?

Oz the Great and Powerful is a wannabe franchise-starter that feels like it never really gets started. There’s a generic hero’s journey, some underwritten characters, mixed messages, and poor casting choices, namely Franco and Kunis. The sense of movie magic is absent and replaced with special attention to marketing opportunities and merchandizing (get your own China Girl, kids). It feels more like the movie is following a pre-planned checklist of stops, cribbing from Alice in Wonderland playbook, and trying to exploit any nostalgia we have for this world and its characters. Except we love Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, the cowardly Lion, and Toto. I don’t think anyone really had any strong affection for Glinda or the Wizard. Just because we’re in the same land with familiar elements doesn’t mean our interest has been satiated. The Wizard of Oz backstory has already been done and quite well by the Broadway show Wicked, based upon the novels by Gregory Maguire. That show succeeded because it focused on the characters and their relationships (extra points for a complicated and positive female friendship dynamic). We cared. That’s the biggest fault in Raimi’s Oz, that amidst all the swirling special effects and fanciful imagination, you watch it without ever truly engaging with it. You may start to wonder if your childlike sense of wonder is dead. It’s not; it’s just that you’re old enough to see a bad movie for what it is.

Nate’s Grade: C

Garden State (2004)

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

Andrew Large Largeman (Braff) is an out-of-work actor living in an anti-depressant haze in LA. He heads back to his old stomping grounds in New Jersey when he learns that his mother has recently died. Andrew has to reface his psychiatrist father (Ian Holm), the source of his guilt and prescribed numbness. He has forgotten his lithium for his trip, and the consequences allow Andrew to begin to awaken as a human being once more. He meets old friends, including Mark (Peter Sarsgaard), who now digs graves for a living and robs them when he can. He parties at the mansion of a friend made rich by the invention of silent Velcro. Things really get moving when Andrew meets Sam (Natalie Portman), a free spirit who has trouble telling the truth and staying still. Their budding relationship coalesces with Andrews re-connection to friends, family, and the joys life can offer.

Braff has a natural directors eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the characters sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but dont feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff has a natural directors eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the characters sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but dont feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff deserves a medal for finally coaxing out the actress in Portman. She herself has looked like an overly medicated, numb being in several of her recent films (Star Wars prequels, Im looking in your direction), but with her plucky, whimsical role in Garden State, Portman proves that her careers acting apex wasn’t in 1994’s The Professional, when she was 12. Her winsome performance gives Garden State its spark, and the sincere romance between Sam and Andrew gives it its heart.

Sarsgaard is fast becoming one of the best young character actors out there. After solid efforts in Boys Don’t Cry and Shattered Glass, he shines as a course but affectionate grave robber that serves as Andrews motivational elbow-in-the-ribs. Only the great Holm seems to disappoint with a rare stilted and vacant performance. This can be mostly blamed on Braff’s underdevelopment of the father role. Even Method Man pops up in a very amusing cameo.

The humor in Garden State truly blossoms. There are several outrageous moments and wonderfully peculiar characters, but their interaction and friction are what provide the biggest laughs. So while Braff may shoehorn in a frisky seeing-eye canine, a knight of the breakfast table, and a keeper of an ark, the audience gets its real chuckles from the characters and not the bizarre scenarios. Garden State has several wonderfully hilarious moments, and its sharp sense of humor directly attributes to its high entertainment value. The film also has some insightful looks at family life, guilt, romance, human connection, and acceptance. Garden State can cut close like a surgeon but it’s the surprisingly elegant tenderness that will resonate most with a crowd.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my play list after I heard it used in the commercials.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my play list after I heard it used in the commercials.

Garden State is not a flawless first entry for Braff. It really is more a string of amusing anecdotes than an actual plot. The film’s aloof charm seems to be intended to cover over the cracks in its narrative. Braff’s film never ceases to be amusing, and it does have a warm likeability to it; nevertheless, it also loses some of its visual and emotional insights by the second half. Braff spends too much time on less essential moments, like the all-day trip by Mark that ends in a heavy-handed metaphor with an abyss. The emotional confrontation between father and son feels more like a baby step than a climax. Braff’s characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.

Garden State is a movie thats richly comic, sweetly post-adolescent, and defiantly different. Braff reveals himself to be a talent both behind the camera and in front of it, and possesses an every-man quality of humility, observation, and warmth that could soon shoot him to Hollywood’s A-list. His film will speak to many, and its message about experiencing lifes pleasures and pains, as long as you are experiencing life, is uplifting enough that you may leave the theater floating on air. Garden State is a breezy, heartwarming look at New York’s armpit and the spirited inhabitants that call it home. Braff delivers a blast of fresh air during the summer blahs.

Nate’s Grade: B

You must be logged in to post a comment.