Blog Archives

Sorry, Baby (2025)

Sundance favorite Sorry, Baby takes several serious subjects and provides its own little bittersweet treatise through a character study of one woman navigating her complex feelings after being assaulted by her college professor. Written, directed, and starring Eva Victor, the movie feels like a combination of one of those small-town slice-of-life hangouts and something a little more arch and peculiar, but it still coasts on its vision and authorial voice. Victor’s portrait rings with honesty and empathy as her character, Agnes, wants to live a “normal life” but doesn’t quite understand what that might be. Her best friend is pregnant from a sperm donor, she’s adjusting to her workload as a literary professor at her alma mater (in an ironic twist, she occupies the same office as her former mentor and attacker), she’s flirting with the possibility of a romance with a nice neighbor (Lucas Hedges), and she just adopted a stray cat. The present, suffused in indecision and depression, is juxtaposed with flashbacks to her before, immediately after the assault, and the infuriating aftermath. This is where some of Victor’s darker sense of humor arises, like when Agnes is consoled by university officials who tell her there’s nothing they can do because her attacker has resigned but, hey, they’re also women, so, you know, they get it. Sorry, Baby walks a fine line between making you wince and making you want to laugh. It’s an impressive debut for Victor on many fronts, though I wish I felt like it amounted to something more emphatic or emblematic. It can feel more like a lot of self-contained scenes than a full movie, like Agnes going through jury selection before being excused when she has to confess her own history and her conflicted view of her attacker. I really enjoyed the concluding monologue Agnes gives to a newborn, explaining that the world she’s just entered will probably eventually hurt her but that there’s still good people and goodness that can be found. It’s heartfelt but in-character and feels completely on her own terms. Sorry, Baby is a little slow and a little closed-off, but it also deals with trauma and perseverance in a manner that doesn’t feel trite, condescending, or misery-prone.

Nate’s Grade: B

Didi (2024)

It feels slightly strange when you acknowledge that coming-of-age movies have long-surpassed your own age of adolescent personal discovery. With Sundance indie Didi, we’ve now brought that time frame up to 2008, where we follow the 13-year-old Chris (Izac Wang), a first-generation Taiwanese-American kid trying to flirt with his junior high crush, get better at skateboarding, edit YouTube videos that people might actually want to see, and perhaps make some new friends during the summer before high school begins. This is one of those movies that lives or dies by its slice-of-life details and sense of authenticity. Writer/director Sean Wang does an excellent job placing the audience in the position of his biographical avatar, Chris. We feel his discomfort trying to navigate the different cultural expectations of home life and school life, the perils of trying to step outside your comfort zone and be rewarded rather than embarrassed. This is compounded by Chris having to endure and brush aside the stereotypes his peers project onto him for being Asian-American. The problem with the movie is that our main character is kind of a twit. He’s so harsh and unfair to his long-suffering mother (Lust, Caution‘s Joan Chen) that his own friends eventually complain about his rude behavior. In a moment of awkward discomfort, he calls his friend’s crush “a whore,” and then describes how he and his friend messed around with the corpse of a squirrel once. He also pees in his older sister’s lotion bottle. The whole “befriending cool skateboarders” storyline goes nowhere, nor does it open up some deeper understanding of our character and his wants, talents, or capabilities. Didi’s real distinct angle could have been growing up in the Internet age, and there it too feels lacking. It all feels a little like we’re spending too much time with the wrong family member. The put-upon mother would have been an even more intriguing person to explore, especially as she yearns to be an artist, deals with her bratty kids, an overbearing mother-in-law living with them without a kind word to say, and a husband half the world away busy working. Getting stuck with the angsty kid feels disappointing.

It feels slightly strange when you acknowledge that coming-of-age movies have long-surpassed your own age of adolescent personal discovery. With Sundance indie Didi, we’ve now brought that time frame up to 2008, where we follow the 13-year-old Chris (Izac Wang), a first-generation Taiwanese-American kid trying to flirt with his junior high crush, get better at skateboarding, edit YouTube videos that people might actually want to see, and perhaps make some new friends during the summer before high school begins. This is one of those movies that lives or dies by its slice-of-life details and sense of authenticity. Writer/director Sean Wang does an excellent job placing the audience in the position of his biographical avatar, Chris. We feel his discomfort trying to navigate the different cultural expectations of home life and school life, the perils of trying to step outside your comfort zone and be rewarded rather than embarrassed. This is compounded by Chris having to endure and brush aside the stereotypes his peers project onto him for being Asian-American. The problem with the movie is that our main character is kind of a twit. He’s so harsh and unfair to his long-suffering mother (Lust, Caution‘s Joan Chen) that his own friends eventually complain about his rude behavior. In a moment of awkward discomfort, he calls his friend’s crush “a whore,” and then describes how he and his friend messed around with the corpse of a squirrel once. He also pees in his older sister’s lotion bottle. The whole “befriending cool skateboarders” storyline goes nowhere, nor does it open up some deeper understanding of our character and his wants, talents, or capabilities. Didi’s real distinct angle could have been growing up in the Internet age, and there it too feels lacking. It all feels a little like we’re spending too much time with the wrong family member. The put-upon mother would have been an even more intriguing person to explore, especially as she yearns to be an artist, deals with her bratty kids, an overbearing mother-in-law living with them without a kind word to say, and a husband half the world away busy working. Getting stuck with the angsty kid feels disappointing.

Nate’s Grade: B-

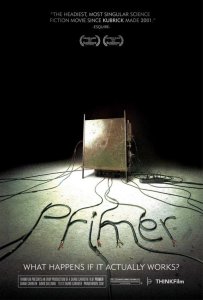

Primer (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released October 8, 2004:

Originally released October 8, 2004:

I was intrigued about Primer because I had been told it was classy, smart sci-fi that’s so often missing in today’s entertainment line-up (see: Sci-Fi channel’s Mansquito). It won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival and the critical reviews had been generally very positive. So my expectations were high for a well wrought, high brow film analyzing time travel. What I got was one long, pretentious, incomprehensible, poorly paced and shot techno lecture. Oh it got bad. Oh did it get bad.

Aaron (Shane Carruth) and Abe (David Sullivan) run a team of inventors out of their garage. Their newest invention seems promising but they’re still confused about what it does. Aaron and Abe’s more commercially minded partners want to patent it and sell it. Aaron and Abe inspect their invention further and discover it has the ability to distort time. They invent larger versions and time travel themselves and thus create all kinds of paradoxes and loops and confusion for themselves and a viewing audience.

Watching Primer is like reading an instruction manual. The movie is practically crushed to death by techno terminology and all kinds of geek speak. The only people that will be able to follow along are those well-versed in quantum physics and engineering. Indeed, Primer has been called an attempt to make a “realistic time-travel movie,” which means no cars that can go 88 miles per hour. That’s fine and dandy but it makes for one awfully boring movie.

Primer would rather confound an audience than entertain them. There is a distinct difference between being complicated and being hard to follow. You’d need a couple volumes of Cliff Notes just to follow along Primer‘s talky and convoluted plot. I was so monumentally bored by Primer that I had to eject the DVD after 30 minutes. I have never in my life started a film at home and then turned it off, especially one I paid good money to rent, but after so many minutes of watching people talk above my head in a different language (techno jargon) I had reached my breaking point. Primer will frustrate most viewers because most will not be able to follow what is going on, and a normal human being can reasonably only sit for so long in the dark.

Primer would rather confound an audience than entertain them. There is a distinct difference between being complicated and being hard to follow. You’d need a couple volumes of Cliff Notes just to follow along Primer‘s talky and convoluted plot. I was so monumentally bored by Primer that I had to eject the DVD after 30 minutes. I have never in my life started a film at home and then turned it off, especially one I paid good money to rent, but after so many minutes of watching people talk above my head in a different language (techno jargon) I had reached my breaking point. Primer will frustrate most viewers because most will not be able to follow what is going on, and a normal human being can reasonably only sit for so long in the dark.

I did restart Primer and watched it to its completion, a scant 75 minutes long. The last 20 minutes is easier to grasp because it does finally deal with time travel and re-staging events. It’s a very long time to get to anything comprehensible. I probably should watch Primer again in all fairness but I have the suspicion that if I did my body would completely shut down on me in defense. Some people will love this and call it visionary, but those will be a very select group. It’s not just that Primer is incomprehensible but the film is also horrifically paced. When you don’t know what’s being said and what’s going on then scenes tend to drag because there is no connection. This movie is soooooo slow and it’s made all the worse by characters that are merely figureheads, dialogue that’s confusing and wooden, and a story that would rather spew ideas than a plot.

Writer/director/star Shane Carruth seems to have high ambitions but he has no empathy for an audience. Films can be dense and thought-provoking but they need to be accessible. Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko is a sci-fi mind bender but it’s also an accessible, relatable, enjoyable movie that’s become a cult favorite. Carruth also seems to think that shooting half the movie out of focus is a good idea.

I’m not against a smart movie, nor am I against science fiction that attempts to explore profound concepts and ideals. What I am against, however, is wasting my time with a tech lecture disguised as quality entertainment. Primer is obtuse, slow, convoluted, frustrating and pretentiously impenetrable. After finally finishing Primer, I scanned the DVD spine and noticed it said, “Thriller.” I laughed so hard I almost fell over. The only way Primer could be a thriller is because you’ll be racing the clock for it to finish.

Nate’s Grade: C-

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I tried, dear reader. I had every intention of giving 2004’s Primer another chance, wanting to allow the distance of time to perhaps make the movie more palatable for my present-day self than it was when I was in my early twenties and irritated by this low-budget, high-concept Sundance DIY time travel indie. I thought with two decades of hindsight, I’d be able to find the brilliance that people cited back in 2004 where instead I only found maddening frustration. I consider myself a relatively intelligent individual, so I felt like I would be able to unpack what has been dubbed the most complex and realistic time travel movie ever created, let alone on a shoestring budget of only $7000, where the showcase was writer/director/star/editor/composer Shane Caruth’s intricate plotting. The whole intention with my re-watches is to give movies another chance and to honestly reflect upon why my feelings might have changed over time, for better or worse. That’s my intent, and while this day may have always been a matter of time for arriving, but I tried valiantly to watch Primer again and I quit. Yes, my apologies, but I tapped out.

I gave the movie twenty minutes before I came to the conclusion that I just wanted to do anything else with my time. I even tried watching a YouTube explanation video to give me a better summation, and even five minutes into that I came to the same conclusion that I wanted to do anything else with my fleeting sense of time. I think this is a case of accessibility and engagement.

Ultimately, this is the tale of two would-be inventors who keep reliving the same day to make money and win over a girl at a party. Reliving this day several times, with several iterations, and literally requiring a flowchart to keep it all together, is a lot of work for something that seemingly offers so little entertainment value beyond the academic pat on the back for being able to keep up with the inscrutable plotting. Look, I love time travel movies. I love the possibilities, the playfulness, the emphasis on ideas and casualty and imagination. I love the questions they raise and the dangers and, above all, the sheer fun. A time travel movie shouldn’t feel like you’re reading a book on arcane tax law. It needs to be, at the very least, interesting. Watching these two guys live out their lives, while on the peripheral more exciting things are happening with doubles, and we’re stuck with watching them migrate to this same party, or this same storage lockers and garages. It’s all so resoundingly low-stakes, even though betrayal and murder appear. I found this drama so powerfully uninteresting, and then structured and skewered and stacked to be an inscrutable, unknowable puzzle that makes you want to give up rather than engage. For me, there isn’t enough investment or intrigue to try and unpack this movie’s homework.

This is a lesson for me, as I have a newborn baby in my house, and sleep deprivation and fatigue are more a presence in my life, that I’m going to be more selective with what I choose to spend those moments of free time. Do I want to invest my time watching a movie I am not engaging with, that gives me so little to hold onto? When my friend Liz Dollard had her first child, she talked about not watching downer movies like 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, only having the emotional space for stories that wouldn’t be draining to her mental well-being. This meant low-stakes, uplifting, generally happy or familiar tales. I remember at the time thinking that she was willfully shuttling so many potential movies from her viewership, great films that could be challenging or depressing and deserving of being seen. Now, I completely get it, because after you’ve woken up several times during that night to feed a small child who has no means of communicating with you other than volcanic screaming, watching a long movie about human suffering can feel like a tall order. While Primer isn’t overwhelming as some kind of miserable dirge, it is too hard for me to access and gives me too little to hold onto.

This is a lesson for me, as I have a newborn baby in my house, and sleep deprivation and fatigue are more a presence in my life, that I’m going to be more selective with what I choose to spend those moments of free time. Do I want to invest my time watching a movie I am not engaging with, that gives me so little to hold onto? When my friend Liz Dollard had her first child, she talked about not watching downer movies like 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, only having the emotional space for stories that wouldn’t be draining to her mental well-being. This meant low-stakes, uplifting, generally happy or familiar tales. I remember at the time thinking that she was willfully shuttling so many potential movies from her viewership, great films that could be challenging or depressing and deserving of being seen. Now, I completely get it, because after you’ve woken up several times during that night to feed a small child who has no means of communicating with you other than volcanic screaming, watching a long movie about human suffering can feel like a tall order. While Primer isn’t overwhelming as some kind of miserable dirge, it is too hard for me to access and gives me too little to hold onto.

As a film critic for over twenty-five years of my life, I try my best to thoughtfully analyze every movie I sit down to write about, and I try to think about potential audiences and the artistic intentions for them, and whether choices help or hinder those intentions. Not every movie is going to be for me just like any other work of media; there are countless musical artists that I will never willfully listen to but have their respective fan bases. I know there are people that love Primer, as hard as it is for me to fathom. I know there are people out there that leap to the challenge of keeping the nine iterations and timelines together as time confusingly folds upon itself. I know there are sci-fi enthusiasts that respect and appreciate the stripped-down, more “realistic” application of time travel. I know there are people who celebrate this movie, but I am not one of them. Primer is simply not for me, and that’s okay. Not every work of art will be for every person. I doubt I’ll ever come back to Primer again for the rest of my life, but there’s so many more movies to watch every day, so why spend precious time on a movie you’re just not clicking with?

Adios, Primer. To someone else, you’re a wonderful movie. To me, you’re, as I wrote in 2004, a “techno lecture” disguised as an impenetrable film exercise.

Re-View Grade: Undetermined

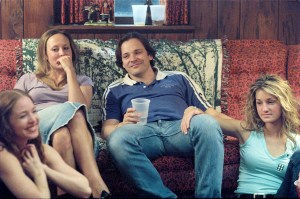

Garden State (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Originally released July 28, 2004:

Zack Braff is best known to most as the lead doc on NBC’s hilarious Scrubs. He has razor-sharp comic timing, a goofy charisma, and a deft gift for physical comedy. So who knew that behind those bushy eyebrows and bushier hair was an aspiring writer/director? Furthermore, who would have known that there was such a talented writer/director? Garden State, Braff’s ode to his home, boasts a big name cast, deafening buzz, and perhaps, the first great steps outward for a new Hollywood voice.

Andrew Large Largeman (Braff) is an out-of-work actor living in an anti-depressant haze in LA. He heads back to his old stomping grounds in New Jersey when he learns that his mother has recently died. Andrew has to reface his psychiatrist father (Ian Holm), the source of his guilt and prescribed numbness. He has forgotten his lithium for his trip, and the consequences allow Andrew to begin to awaken as a human being once more. He meets old friends, including Mark (Peter Sarsgaard), who now digs graves for a living and robs them when he can. He parties at the mansion of a friend made rich by the invention of silent Velcro. Things really get moving when Andrew meets Sam (Natalie Portman), a free spirit who has trouble telling the truth and staying still. Their budding relationship coalesces with Andrews re-connection to friends, family, and the joys life can offer.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff has a natural director’s eye for visuals and how to properly use them to convey his characters’ feelings. A scene where Andrew wears a shirt and blends into the wall is a perfect visual note on the character’s sleep-walk through life. Braff’s writing is also familiar but satisfyingly unusual, like a repackaging of old stories told with a confident voice. His characters are interesting and memorable, but don’t feel uselessly quirky, unlike the creations of other first-time indie writers. The melancholy coming-out of Andrew from disconnected schlub to post-pharmaceutical hero really grabs the audience and gives them a rooting point. At times, though, it seems as though Braff may be caught up trying to craft a movie that speaks to a generation, and some will see Garden State as a generation’s voice of a yearning to feel connected.

Braff deserves a medal for finally coaxing out the actress in Portman. She herself has looked like an overly medicated, numb being in several of her recent films (Star Wars prequels, I’m looking in your direction), but with her plucky, whimsical role in Garden State, Portman proves that her careers acting apex wasn’t in 1994’s The Professional when she was 12. Her winsome performance gives Garden State its spark, and the sincere romance between Sam and Andrew gives it its heart.

Sarsgaard is fast becoming one of the best young character actors out there. After solid efforts in Boys Don’t Cry and Shattered Glass, he shines as a coarse but affectionate grave robber that serves as Andrew’s motivational elbow-in-the-ribs. Only the great Holm seems to disappoint with a rare stilted and vacant performance. This can be mostly blamed on Braff’s underdevelopment of the father role. Even Method Man pops up in a very amusing cameo.

The humor in Garden State truly blossoms. There are several outrageous moments and wonderfully peculiar characters, but their interaction and friction are what provide the biggest laughs. So while Braff may shoehorn in a frisky seeing-eye canine, a knight of the breakfast table, and a keeper of an ark, the audience gets its real chuckles from the characters and not the bizarre scenarios. Garden State has several wonderfully hilarious moments, and its sharp sense of humor directly attributes to its high entertainment value. The film also has some insightful looks at family life, guilt, romance, human connection, and acceptance. Garden State can cut close like a surgeon but it’s the surprisingly elegant tenderness that will resonate most with a crowd.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Braff’s film has a careful selection of low-key, highly emotional tunes by artists like The Shins, Coldplay, Zero 7, and Paul Simon. The closing song, the airy Let Go by Frou Frou, has been a staple on my playlist after I heard it used in the commercials.

Garden State is not a flawless first entry for Braff. It really is more a string of amusing anecdotes than an actual plot. The film’s aloof charm seems to be intended to cover over the cracks in its narrative. Braff’s film never ceases to be amusing, and it does have a warm likeability to it; nevertheless, it also loses some of its visual and emotional insights by the second half. Braff spends too much time on less essential moments, like the all-day trip by Mark that ends in a heavy-handed metaphor with an abyss. The emotional confrontation between father and son feels more like a baby step than a climax. Braff’s characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.

Garden State is a movie thats richly comic, sweetly post-adolescent, and defiantly different. Braff reveals himself to be a talent both behind the camera and in front of it, and possesses an every-man quality of humility, observation, and warmth that could soon shoot him to Hollywood’s A-list. His film will speak to many, and its message about experiencing lifes pleasures and pains, as long as you are experiencing life, is uplifting enough that you may leave the theater floating on air. Garden State is a breezy, heartwarming look at New York’s armpit and the spirited inhabitants that call it home. Braff delivers a blast of fresh air during the summer blahs.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

In the summer of 2024, there were two indie movies that defined the next years of your existence. If you were under 18, it was Napoleon Dynamite. If you were between 18 and 30, it was Garden State. Zack Braff’s debut as writer/director became a Millennial staple on DVD shelves, and I think at one time it might have been the law that everyone had to own the popular Grammy-winning soundtrack. It wasn’t just an indie hit, earning $35 million on a minimal budget of $2.5 million; it was a Real Big Deal, with big-hearted young people finding solace in its tale of self-discovery and shaking loose from jaded emotional malaise. If you had to determine a list of the most vital Millennial films, not necessarily on quality but on popularity and connection to the zeitgeist, then Garden State must be included. Twenty years later, it’s another artifact of its time, hard to fully square outside of that influential period. It’s a coming-of-age tale wrapped up in about every quirky indie trope of its era, including a chief example of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, even though that term was first coined from the AV Club review of 2005’s Elizabethtown. Twenty years later, Garden State still has some warm fuzzies but loses its feels.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Andrew Largeman (Braff) is a struggling actor in L.A. who returns to his hometown in New Jersey to attend the funeral of his mother. Right there we have the prodigal son formula mixed with the return-to-your-roots formula, wherein the cynical figure needs to learn about the important things they’ve forgotten from the good people they left behind for supposed bigger and better things in the big city. There’s a lot of familiarity with Garden State, both intentionally and unintentionally. It’s meant to evoke the loose, rougher-edged romantic comedies of Hal Ashby and older Woody Allen. It certainly feels more like a series of scenes than a united whole, and that can work in Braff’s favor. His character has gone off his meds for the first time since he was a child, and he’s experiencing a personal reawakening. He’s opening himself up more to the people and possibility of the world, so the movie works more on a thematic level to unify itself rather than strictly from a foundational plot with key turns. If you can connect on that relatable level, then you will likely be able to experience the same whimsy and enchantment that so many felt back in 2004. However, with twenty years of distance, I now see more seams than when I was but a wide-eyed 22-year-old romantic. Andrew is more a reactive symbol, more personified by his hardships or inability to chart a path for himself than by a personality. He’s easily eclipsed by the quirky characters dancing all around him, with Braff smiling ever so wryly at the sweet mysteries of life. This stop-and-smell-the-roses approach was also explored in 2014’s Wish I Was Here, Braff’s directing follow-up that placed him as a family man questioning himself amidst marital malaise. This movie was far less celebrated, I think, because of the thematic redundancy but also because Braff was playing an older character that needed to, kind of, grow up. It was more tolerable when Braff was playing a mid-20s melancholic experiencing his first brush with romantic love. Less so ten years later.

Natalie Portman had been an actress that I was more cool over until 2004 with the double-whammy of Garden State and her Oscar-nominated turn in Closer. She’s since become one of the most exciting actors who goes for broke in her performances whether they might work or not. In 2004, I thought her performance in Garden State was an awakening for her, and in 2024 it now feels so starkly pastiche. Bless her heart, but Portman is just calibrated for the wrong kind of movie. Her energy level is two to three times that of the rest of the movie, and while you can say she’s the spark plug of the film, the jolt meant to shake Andrew awake, her character comes across more as an overwritten cry for help. Sam is even more prototypical Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) than Kirsten Dunst’s bouncy character in Elizabethtown. Her entire existence is meant to provoke change upon our male character. This in itself is not an unreasonable fault; many characters in numerous stories are meant to represent a character’s emotional state. It’s just that there isn’t much to Sam besides a grab-bag of quirky characteristics: she’s a compulsive liar, though nothing is ever really done with this being a challenge to building lasting bonds; she’s incapable of keeping pets alive, and Andrew could be just another pet; she’s consumed with being unique to the point of having to stand up and blurt out nonsense words to convince herself that nobody in human history has duplicated her recent combination of sounds and body gestures, but she’s all archetype. She exists to push Andrew along on his reawakening, including introducing him and us to The Shins (“This song will change your life”). She’s entertaining, and Portman is charming, but it’s an example of trying so hard. I thought her cheeks must have hurt from holding a smile so long. I’m sure Braff would compare Sam to Annie Hall, as Diane Keaton was perhaps the mold for the MPDG, except she more than stood on her own and didn’t need a nebbish man to complete her.

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

There are some enjoyable moments. It’s funny to watch a young Jim Parsons in a suit of armor eating breakfast cereal and expounding the romance language of Klingon. It’s funny to have a meet-cute in a doctor’s office while Andrew is repeatedly humped by a dog with personal boundary issues. It’s fun to go on a madcap journey around town with your former high school friend-turned-gravedigger that ends up in a sinkhole in a quarry, where characters can literally scream into the void. It’s darkly funny to run into a former classmate who became a cop who is still a screw-up except now he has authority. It’s poignant to listen to Andrew’s story about accidentally paralyzing his mother when he was an angry young child who, in a fit of rage, pushed her, and she hit her head on a faulty dishwasher latch. Given all these elements an overview, it feels like Garden State was Braff’s very loose collection of ideas and stories, jokes and bits collected over the years. It’s entertaining and quirky and silly and occasionally poignant, but it’s never more than the sum of its parts. Garden State wants to be about a man changing his life and perspective, but it’s really more a Wizard of Oz-style journey through the quirky indie backlot of kooky Jersey characters. The scenes with Andrew’s distant father (Ian Holm) feel too removed to have the catharsis desired. He feels like an absent character from the movie, so why should we overly value this father-son reconciliation?

Admittedly, that soundtrack is still a banger. It soars when it needs to, like Imogen Heep’s “Let Go” over the race-back-to-the-girl finale, and it’s deftly somber when it needs to, like Iron and Wine’s cover of “Such Great Heights” and “The Only Living Boy in New York” paired with our big movie kiss. It’s such a cohesive, thematic whole that lathers over the exposed seams of the movie’s scenic hodgepodge. Braff tried to find similar magic with his musical choices for 2006’s The Last Kiss, a movie he starred in but did not direct (he also provided un-credited rewrites to Paul Haggis’ adapted screenplay). That soundtrack is likewise packed with eclectic artists (he even snags Aimee Mann) but failed to resonate like Garden State. It’s probably because nobody saw the movie and Braff’s character was, as I described in my 2006 review, an overgrown man-child afraid his life lacks “surprises” now that he was going to be a father. Sheesh.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Garden State is a movie that is winsome and amusing but also emblematic of its early 2000s era, of young people yearning to feel something in an era where we were afraid of feeling too much because of how painful the real world stood to be as an adult. Rejecting pain is rejecting the full human experience, which we even learned in Inside Out. There could have been a richer examination on parental desire to protect children from experiencing pain but creating more harm than good (kind of the theme of 2018’s God of War reboot). It’s just not there. My original review was far more smitten with the movie, doubled over by Portman’s performance and the effectiveness of Braff as a writer and a director. My criticisms at the end of my 2004 review are all shared with my present-day self, especially the dialogue: “Characters also talk in a manner that less resembles reality and more resembles snappy, glib movie dialogue. It’s still fun and often funny, but the characters speak more like they’ve been saving up witty one-liners just for the occasion.” I’d downgrade the movie ever so slightly, though there is still enough charm and whimsy to separate it from its twee indie brethren. In 2004, Garden State felt like a seminal movie for a breakthrough filmmaker. Now it feels like a fitfully amusing rom-com with slipshod plotting and a supporting character that needed re-calibration.

Re-View Grade: C+

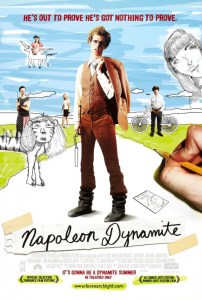

Napoleon Dynamite (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released June 11, 2004:

Originally released June 11, 2004:

Napoleon Dynamite was an audience smash at the 2004 Sundance film festival. Fox Searchlight jumped at the chance to distribute a film written and directed by Mormons, starring a Mormon, and set in film-friendly Idaho. MTV Films, the people behind alternating good movies (Better Luck Tomorrow, Election) and atrocious movies (Crossroads, Joe’’s Apartment, an upcoming film actually based on Avril Lavigne’s “Sk8r Boi” song), came aboard and basically said, “Look, we really like the movie, and we want to help bring it to a wider, MTV-influenced audience.” And thus, Napoleon Dynamite seems to have become the summer biggest must-see film for sk8r bois and sk8r grrrls nationwide.

Napoleon Dynamite (John Heder) is an Idaho teen that marches to the beat of his own drum. He lives with his Dune Buggy riding grandmother and 31-year-old brother Kip (Aaron Ruell), who surfs the Web talking to women. When their grandma gets injured, Uncle Rico (John Gries), stuck in the 80s in fashion and mind, takes up shop in the Dynamite home and coerces Kip to hustle money from neighbors. Meanwhile, Napoleon befriends Deb (Tina Majorino), an otherwise normal girl with a sideways ponytail, and Pedro (Efren Ramirez, who was actually in Kazaam!), the new kid at school. Together, they try and get Pedro elected to class president, but standing in their way is the mighty shadow of Summer (Haylie Duff), the most popular girl in school. Oh yeah, there’’s also a llama.

First time director, Jared Hess, and first time cinematographer, Munn Powell, orchestrate shots very statically, with little, simple camera movements and many centered angles. The style is reminiscent of the films of Todd Solondz (Welcome to the Dollhouse), or, more precisely, Wes Anderson. This shooting technique makes the characters stand out even more, almost popping out at you behind flat backgrounds like some Magic Eye picture. Hess easily communicates the tedium of Idaho with his direction. Can anyone name any other film that takes place entirely in Idaho? (Please note that My Own Private Idaho takes place in Portland and Seattle, mostly).

First time director, Jared Hess, and first time cinematographer, Munn Powell, orchestrate shots very statically, with little, simple camera movements and many centered angles. The style is reminiscent of the films of Todd Solondz (Welcome to the Dollhouse), or, more precisely, Wes Anderson. This shooting technique makes the characters stand out even more, almost popping out at you behind flat backgrounds like some Magic Eye picture. Hess easily communicates the tedium of Idaho with his direction. Can anyone name any other film that takes place entirely in Idaho? (Please note that My Own Private Idaho takes place in Portland and Seattle, mostly).

The star of the show is, of course, Heder. His wickedly funny deadpan delivery helps to create a truly memorable character. He achieves a geek Zen and, judging from the incredible amount of kids under-14 that appeared both times I saw this film, is most likely the greatest film realization of a dork. It’s grand dork cinema, a genre long ignored after the collapse of the mighty Revenge of the Nerds franchise. So while Napoleon isn’’t exactly relatable (llamas, Dune Buggy grannies and all), the right audience will see reflections of themselves. You’’ll be quoting from Napoleon all summer.

Napoleon Dynamite is going to be an acquired taste. It’s filled to the brim with stone-faced absurdities and doesn’’t let up. If you’’re not pulled in with the bizarre antics of bizarre characters in the first 10 minutes, then you may as well leave because otherwise it will feel like the film is wearing you down with its “indie weirdness.” Napoleon Dynamite seems to skirt the sublimely skewed world of Wes Anderson, but Napoleon lacks the deep humanity of Anderson’s films. What the audience is left with is a sugary, sticky icing but little substance beneath, and, depending on your sweet tooth, it’’ll either be overpowering and a colossal disappointment or it’’ll taste just right for the occasion. Alright, I’’m done with baking analogies for the year.

Some will find a certain condescension against the characters. Napoleon Dynamite doesn’’t outright look down upon its characters, but it does give them enough room to paint themselves fools. Uncle Rico is really the film’s antagonist, yet he’s too buffoonish to be threatening. It’’s a fine line for a film to have condescension toward its characters, but Napoleon Dynamite ultimately leaves with a bemused appreciation for its characters. The film presents the “good” characters as unusual but lovable and ready for growth (Kip, Pedro, and of course Napoleon), but the “bad” characters (Summer, Uncle Rico) aren’’t demonized. In essence, Napoleon Dynamite is the best example of a film that makes an audience laugh at and with its characters simultaneously.

Some will find a certain condescension against the characters. Napoleon Dynamite doesn’’t outright look down upon its characters, but it does give them enough room to paint themselves fools. Uncle Rico is really the film’s antagonist, yet he’s too buffoonish to be threatening. It’’s a fine line for a film to have condescension toward its characters, but Napoleon Dynamite ultimately leaves with a bemused appreciation for its characters. The film presents the “good” characters as unusual but lovable and ready for growth (Kip, Pedro, and of course Napoleon), but the “bad” characters (Summer, Uncle Rico) aren’’t demonized. In essence, Napoleon Dynamite is the best example of a film that makes an audience laugh at and with its characters simultaneously.

Napoleon Dynamite is assuredly an odd duck. Some will cheer; others will want to head out the door after a few minutes. It’’s hard to say which reaction an individual will have. If you have a geek-enriched history populated with unicorns, Dungeons and Dragons, and/or social ostracism, then you may be more inclined to admire Napoleon Dynamite. I laughed out loud throughout the film and found it to be an enjoyable diversion, and I went the whole review without one Jimmy Walker reference.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I feel like trying to explain the unexpected pop-culture success of Napoleon Dynamite is a fool’s errand, ultimately leaving one sputtering out and ending with the disappointing culmination, “Well, you just had to be there, I guess.” It was 2004, before the rise of YouTube and dominant social media outlets, and for whatever reason, if you were under 30, you probably fell in love with this Idaho nerd, or at least fell in love sounding like this Idaho nerd. I couldn’t travel more than a few blocks without overhearing some loitering Millennial uttering, “Gawsh” in mock exasperation, or mentioning llamas, tater tots, ligers, or catching a significant other a “delicious bass.” If you can recall how annoying and omnipresent the Borat impressions were after that 2006 movie’s mainstream splash, well the silver lining to every person, usually a smirking male member of the species, saying, “My wiiiiiiife,” was that it finally pushed aside everyone else endlessly imitating Napoleon Dynamite (John Heder). This movie was everywhere in 2004. It was meme-ified before meme culture became prevalent. Re-watching this movie twenty years later is like excavating a novelty from a different time and trying to better analyze why this silly and stupid little movie about weirdos living their weird lives became a zeitgeist breakout.

If I had to explain the appeal of Napoleon Dynamite, I think it serves as the next step in the evolution of comedy for younger adults. The Muppets are a deservedly celebrated comedy troupe for over 50 years, and beyond the iconic characters and their mirthful camaraderie, I think their ongoing appeal is that it’s an introduction to the forms of irony for younger children. It’s teaching that there can be more behind the silly, and Napoleon Dynamite takes that PG-comedy baton and pushes it forward, as its entire being is one of ironic comedy. The entire movie is built upon the viewer finding the behavior and banter of these characters hilarious for being so straight. There aren’t really jokes in the traditional sense of setups and payoffs; every line has the potential to be a joke because it’s a character saying something ridiculous without the awareness of being ridiculous. As I said back in 2004, “If you’’re not pulled in with the bizarre antics of bizarre characters in the first 10 minutes, then you may as well leave because otherwise it will feel like the film is wearing you down with its “indie weirdness.” Perhaps this style of comedy, a feature fully dedicated to ironic detachment, served as an awakening for others in my age-range, who championed the absurdity of the everyday and lionized the liger-loving man. This movie doesn’t achieve the larger artistic ambitions in a heightened tone of a Wes Anderson or a Yorgos Lanthimos, two masters of droll deadpans. It’s not deep. It’s not complicated. It’s always obvious, but that made the comedy all the more accessible to so many, especially for younger teens and kids.

As a movie, Napoleon Dynamite can be overwhelming. Seeing any clip of this movie serves the same comedy function as watching the entire 96-minute experience. It helps to structure the movie around a nerd’s quest to win over the girl and help his fellow outcasts. It has a recognizable us-versus-them formula where we can root for the weirdos to, if not prove their naysayers wrong, at least prove to one another that they have found acceptance from the ones who matter. It works on that familiar territory. Napoleon’s big dance at the talent show is his triumph, showcasing to the rest of the school his skills, though he runs away before the adulation can be felt, robbing his character of the perceived victory but giving it to the audience instead.

For most of the people involved in this movie, they had a brief burst of wider success before gradually coming back down to Earth. Heder was the obvious breakout and was given bigger supporting roles in studio comedies like Just Like Heaven, School for Scoundrels, Blades of Glory, and Surf’s Up, the other animated penguin movie from 2006. Heder has worked almost exclusively in the realm of voice acting in the last decade, including 2024’s Thelma the Unicorn, directed by Jared Hess and co-written by Jared and his wife Jerusha, the same creative team that gave us Napoleon Dynamite. I never really vibed with any other Hess comedy. I didn’t get the love for 2006’s Nacho Libre, and from there the movies just got worse to unwatchable, like Gentlemen Broncos and Don Verdean, each trying to chase that same combination of detached irony and quirk that proved so successful for them in 2004. I think the inability to follow-up Napoleon Dynamite with another breakout comedy of its ilk speaks to the unpredictable nature of assembling the right mixture of actors, tone, and material, as well as good timing. Would Napoleon Dynamite have been as big a success in 2009 as opposed to 2004? Maybe not. There was a six-episode animated TV series version in 2012, and the fact that I never remembered this probably answers the question over whether the filmmakers got lucky in 2004.

Napoleon Dynamite is the exact same movie it was back in 2004 as it now resides in 2024, and forever more. It’s flat, detached, silly, light-hearted and the same joke on repeat, and if you feel yourself gravitating toward that comedy wavelength, then hop on and enjoy. Re-watching it for me was like revisiting a fad from the past that was hard to put into context. What was it that made so many buy “Vote for Pedro” T-shirts and talk about throwing footballs over mountains? Comedies more than any other movie lend themselves to audience dissemination, to take the jokes and moments and characters and run with them. Nearly every successful comedy has experienced some form of this, so why should Napoleon Dynamite be any different? It’s perfectly understandable to watch this movie unfazed, unamused, and questioning what exactly people found so amusing about this guy and his extended family and friends back in 2004. It’s also understandable to smile and chuckle at the absurdities played so matter-of-factly. Gawsh.

Re-View Grade: B-

Past Lives (2023)

The world of cinema is rife with romantic tales of two people from the past reconnecting and rekindling a passion, learning to love again as older adults now presumably wiser. The Hallmark Christmas industry is practically built from this plot structure, as the man or woman, usually the woman, goes back home to rediscover that their old friend or former flame is still living a humble life and ready to teach him or her about the small pleasures of a simple life. It’s also human nature to think about paths not taken and wonder what may have been. That’s where Past Lives starts and that’s also where it differs. The small-scale indie drama getting some of the best reviews of 2023 follows Nora (Greta Lee) as a thirty-something writer who immigrated to the United States when she was twelve. One of the friends she left behind in South Korea was Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), the boy she was crushing on who she finds again as an adult. In their early twenties, Nora and Hae Sung reconnect online and grow close again, though she requests they take time apart as their lives will not allow them to physically meet again until at least a year later. He agrees. Cut to another twelve years later, and Hae Sung seeks out his old friend, except now Nora is married to another writer, Arthur (John Magaro). What will happen with their 24-years-in-the-making reunion actually takes place?

The world of cinema is rife with romantic tales of two people from the past reconnecting and rekindling a passion, learning to love again as older adults now presumably wiser. The Hallmark Christmas industry is practically built from this plot structure, as the man or woman, usually the woman, goes back home to rediscover that their old friend or former flame is still living a humble life and ready to teach him or her about the small pleasures of a simple life. It’s also human nature to think about paths not taken and wonder what may have been. That’s where Past Lives starts and that’s also where it differs. The small-scale indie drama getting some of the best reviews of 2023 follows Nora (Greta Lee) as a thirty-something writer who immigrated to the United States when she was twelve. One of the friends she left behind in South Korea was Hae Sung (Teo Yoo), the boy she was crushing on who she finds again as an adult. In their early twenties, Nora and Hae Sung reconnect online and grow close again, though she requests they take time apart as their lives will not allow them to physically meet again until at least a year later. He agrees. Cut to another twelve years later, and Hae Sung seeks out his old friend, except now Nora is married to another writer, Arthur (John Magaro). What will happen with their 24-years-in-the-making reunion actually takes place?

Past Lives is a very gentle and sparse movie, and it’s remarkable that this is the debut film from writer/director Celine Song (TV’s Wheel of Time). She has the patience of an artist who knows exactly the vibe they are going for. It’s so confident with those long takes, prolonged pauses, and visual metaphors. Even the plot structure is reflective of her patience, with the adult reunion not even occurring until 50 minutes in and all three parties not meeting until 80 minutes. The opening scene spies all three of our main characters at the bar while two off-screen eavesdroppers provide their own speculative interpretation of the relationship of the three; are they lovers, are they family, who is who? It’s such a smart yet playful way to open her movie, presenting the three main players and then having unseen spectators theorize who they are, providing voice to the audience as we begin to question who might feel closer to whom. It’s also a scene that left me immediately confident that Song was going to be an assured storyteller from here on out.

Past Lives is a very gentle and sparse movie, and it’s remarkable that this is the debut film from writer/director Celine Song (TV’s Wheel of Time). She has the patience of an artist who knows exactly the vibe they are going for. It’s so confident with those long takes, prolonged pauses, and visual metaphors. Even the plot structure is reflective of her patience, with the adult reunion not even occurring until 50 minutes in and all three parties not meeting until 80 minutes. The opening scene spies all three of our main characters at the bar while two off-screen eavesdroppers provide their own speculative interpretation of the relationship of the three; are they lovers, are they family, who is who? It’s such a smart yet playful way to open her movie, presenting the three main players and then having unseen spectators theorize who they are, providing voice to the audience as we begin to question who might feel closer to whom. It’s also a scene that left me immediately confident that Song was going to be an assured storyteller from here on out.

A soapier and more melodramatic version of this story would center on whether Nora is going to have an affair with her childhood sweetheart; even Arthur recognizes in the “Hollywood movie” version of these events that he would be the white American villain standing in the way of true love. Except it’s not that at all. Past Lives is about two former friends and possibly romantic partners reconnecting but it’s not about whether there are still old feelings that will be rekindled. It’s not likely that after a dozen years these two would so quickly fall in love and run away together, so please don’t pretend like this is some kind of spoiler. Instead, the meeting of someone who was once important in their lives allows for a pause point to reflect not what could have been, as Hae Sung is wont to do as he imagines a life where he and Nora were linked, but as the person they used to be and how they have changed into the person they now are. This is how Nora sees their encounter, an opportunity through her childhood friend who stayed to serve as her own “what if.” Not what if she had ever gotten romantically involved with this man but what if she had stayed in Korea rather than immigrating to a new life in the West. There’s also a rosy presumption at play here, where people assume the road not taken would have led to an unmet present happiness. There’s just as much if not more a likelihood that had Nora stayed, and had she dated Hae Sung, that they could have eventually broken up on bad terms and want nothing to do with one another. By leaving young, and by never fulfilling that initial spark, they are both eternally preserved as meaningful people without regret coming into their (past) lives. Granted, every viewer can surmise their own interpretation, especially with a movie so powerfully understated, but my assessment of the movie was less romantic revisionism and more personal accounting.

The movie hinges on three characters, so it’s a good thing that all three actors are compelling to watch. The nuance each of these three performers displays is amazing. They have to communicate much through gestures and glances, where a simple smile allowing oneself to acknowledge the significance of a hug a dozen years in the making are the tools of communication. This is the kind of movie where you can watch the characters processing their thoughts in real time. Lee (The Morning Show, Russian Doll) has the difficult job of navigating as the woman in between past and present, between her husband and this other man from her old life, and she does so with uncommon grace. Yoo (Decision to Leave) is the most reserved as the interloper who doesn’t know what is safe to reveal about himself and his interior life. He confides that he and his ex-girlfriend are on a break because he feels like he’s weighing her down, that he’s too ordinary and thus inferior for her. Then there’s Magaro (The Many Saints of Newark) who might just be the most understanding husband of all time. He’s not going to make a big stink and encourages his wife to see this old friend. There’s a nice moment where Arthur reveals one reason he learned Korean was because Nora would talk in her sleep in Korean. He wanted to learn more about a hidden part of her life. “It’s like there’s a whole place inside you I can’t go,” he says, and rather than seem like jealousy, it’s an admission of wanting to empathize with as many facets of the person you love. No wonder Hae Sung, despite himself, liked Arthur.

The movie hinges on three characters, so it’s a good thing that all three actors are compelling to watch. The nuance each of these three performers displays is amazing. They have to communicate much through gestures and glances, where a simple smile allowing oneself to acknowledge the significance of a hug a dozen years in the making are the tools of communication. This is the kind of movie where you can watch the characters processing their thoughts in real time. Lee (The Morning Show, Russian Doll) has the difficult job of navigating as the woman in between past and present, between her husband and this other man from her old life, and she does so with uncommon grace. Yoo (Decision to Leave) is the most reserved as the interloper who doesn’t know what is safe to reveal about himself and his interior life. He confides that he and his ex-girlfriend are on a break because he feels like he’s weighing her down, that he’s too ordinary and thus inferior for her. Then there’s Magaro (The Many Saints of Newark) who might just be the most understanding husband of all time. He’s not going to make a big stink and encourages his wife to see this old friend. There’s a nice moment where Arthur reveals one reason he learned Korean was because Nora would talk in her sleep in Korean. He wanted to learn more about a hidden part of her life. “It’s like there’s a whole place inside you I can’t go,” he says, and rather than seem like jealousy, it’s an admission of wanting to empathize with as many facets of the person you love. No wonder Hae Sung, despite himself, liked Arthur.

And yet the curmudgeon in me, the yin to my foolishly romantic self’s yang, has some qualms about what holds Past Lives back from being the emotional tour de force it could have been. This is because the characters are understated to the point that they feel less fully formed as people so that a larger selection of viewers will recognize themselves and their own questions and relatability. In making the film more universal, the movie has also made the characters feel less defined, more informed by key details of difference that the characters list like employee evaluations. Nora thinks like an American woman and Hae Sung thinks like a Korean man. In some ways, they’re meant to be stand-ins for Eastern and Western cultural differences. Understatement is grand but it can also leave less specifics. Think about how remarkable the characters are in Richard Linklater’s Before series, their mellifluous conversations so natural and pleasant to behold. It’s the same key aspect with many of the mumblecore indies, dropping you in on lives and characters that you want to observe for 100-or-so minutes of investment. They leave an impression because of who they are, whereas much of Past Lives is leaving an impression of reflection of who they could have been and how they might have changed over time. It’s not quite the same, and so this is why my emotional and intellectual investment were not as steadily satisfied by the full film.

Aching to the point of being painful, Past Lives is a beautifully tender drama about characters taking stock of their lives both past and present. It’s like somebody mixed Before Sunset with a French New Wave romance. A key theme throughout is the concept of fate, known as “In Yun” in Korea. It’s about the many actions and ripples through years and years to bring people into contact with one another and recognizing that every connection is the result of thousands of these actions pushing us to that singular point. It’s a way to say be appreciative of what you have but also who you’ve been allowed to become. Past Lives is an appealing story that might be a bit too understated to break through higher levels of emotional engagement, but even at its current level, it’s still one of the finer films of the year.

Aching to the point of being painful, Past Lives is a beautifully tender drama about characters taking stock of their lives both past and present. It’s like somebody mixed Before Sunset with a French New Wave romance. A key theme throughout is the concept of fate, known as “In Yun” in Korea. It’s about the many actions and ripples through years and years to bring people into contact with one another and recognizing that every connection is the result of thousands of these actions pushing us to that singular point. It’s a way to say be appreciative of what you have but also who you’ve been allowed to become. Past Lives is an appealing story that might be a bit too understated to break through higher levels of emotional engagement, but even at its current level, it’s still one of the finer films of the year.

Nate’s Grade: B+

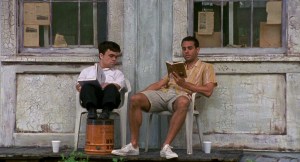

The Station Agent (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released December 5, 2003:

Originally released December 5, 2003:

This is the most charming film of 2003, and Im not just saying this because I had an interview with one of its stars, Michelle Williams (Dawson’s Creek). Fnin McBride (Peter Dinklage) is a man with dwarfism. With every step he takes every look he gives, you witness the years of torture hes been through with glares and comments. Hes shut himself away from people and travels to an isolated train station to live. There he meets two other oddballs, a live-wire hot dog vendor (Bobby Cannavale) and a divorced mother (Patricia Clarkson). Together the three find a wonderful companionship and deep friendship. The moments showing the evolution of the relationship between the three are the films highlights. Its a film driven by characters but well-rounded and remarkable characters. Dinklage gives perhaps one of the coolest performances as the unforgettable Fin. Cannavale is hilarious as the loudmouth best friend that wants a human connection. Clarkson is equally impressive as yet another fragile mother (a similar role in the equally good Pieces of April). The writing and acting of The Station Agent are superb. Its an unforgettable slice of Americana brought together by three oddballs and their real friendship. You;ll leave The Station Agent abuzz in good feelings. This is a film you tell your friends about afterwards. There’s likely no shot for a dwarf to be nominated for an Oscar in our prejudiced times but Dinklage is deserving. The Station Agent is everything you could want in an excellent independent movie. It tells a tale that would normally not get told. And this is one beauty of a tale.

Nate’s Grade: A

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

Tom McCarthy didn’t invent the quirky, found family indie but he sure seems to have nearly perfected it, starting with 2003’s The Station Agent. This little gem of a movie is so subdued, so relaxed, and so gentle that it seems to adopt the very personality of its lead character, Fin (Peter Dinklage), a dwarf who just likes trains a lot and wants to live his life in solitude. He’s an unassuming man who keeps to himself as a means of survival, because almost every time he goes into public life Fin is met with stares, snickers, and harassment (the convenience store lady gets his attention to take his unsolicited picture). Very few will get to know this man beyond his superficial physical characteristics, so he retreats within himself, perhaps purposely obsessing over an antiquated hobby as a means of escape to the past. He’s a lonely man and the movie is about him finding his clan, his place in the world, by slowly lowering his defenses. It’s a simple sort of story that is lifted by the strength of its characters and its wonderful ensemble cast.

With such a taciturn main character we need a contrasting character, a much more talkative person with high energy, and this is beautifully embodied by Bobby Cannavale. He plays Joe Oramas, a coffee truck operator who exemplifies joy de vie. He’s charming, garrulous, and relentlessly upbeat, which makes for a magnificent odd couple contrast with Fin, and it allows both characters to gradually change and grow attached to one another’s mutual friendship. Finn allows himself to become more vulnerable and form bonds and Joe starts to see the world from Fin’s point of view, allowing himself to slow down and appreciate the smaller things he might have missed in his excitable and irascible activity. Dinklage’s dry understated performance is a perfect counterpoint to the churning energy emanating from a grinning Cannavale. This is a fine showcase of both actors, who would go on to win six Emmys between them in the years ahead.

The third member of this found family is Olivia, played by Patricia Clarkson, and I actually think the movie might have worked better without her character. She does provide a point of view that our two guys lack; she’s experienced significant grief over a lost child and her life is in shambles as she tries to discover what she wants from her cratering marriage to a young-er John Slattery. Clarkson is also wryly enjoyable and gets some of the best lines in the movie, so she’s not at fault here. I think it’s because I’m confused about how this character is treated, especially compared to the natural opposites-attract dynamic of Fin and Joe’s friendship. Olivia feels like a broken thing that the boys need to try and help get better, but we were already covering this with Finn’s reserve from a lifetime of feeling ostracized. The possible romance between Fin and Olivia is also awkward because there are obvious implications that she sees Fin as a replacement son, even having him sleep in her son’s old bed. At one point, in her anger, she yells at Fin that she’s not his mother, but it feels much more like she’s the one who is looking for a surrogate son, and just because Fin is a dwarf and perhaps of similar heights makes the whole thing feel uncomfortable and ill-advsied. I’m not going to refuse an added Patricia Clarkson in my movie, but upon my re-watch twenty years later, it’s hard not to feel like McCarthy didn’t have as much envisioned for this part.

McCarthy’s movie acclimates the viewer to the simple charms of its people and the small town, getting to know the various characters and their foibles and hopes, getting used to the rhythms of this life and adjusting much like Fin. There are small victories that are payoffs, like Fin finally getting a library card, or speaking in front of a school class about his affinity for trains. It works so well. McCarthy continued his found family writing with 2007’s The Visitor and 2011’s Win Win, both anchored by the emotional enormity of sad, lonely men learning to open up to companionship. There were some dips in the road but McCarthy worked his found family magic to the biggest stage with 2015’s Best Picture winner, Spotlight, which McCarthy directed and co-wrote. His only follow-up theatrical movie was 2021’s Stillwater, where an oil rig dad (Matt Damon) tries to save his daughter overseas from a very ripped-from-the-headlines scandal (Amanda Knox was very unhappy). There is also a 2020 Disney Plus movie about a kid detective and his imaginary polar bear best friend (that actually sounds adorable). I guess I figured a Best Picture Oscar on your resume, as well as a history of working within the studio system and world of indies, would have given McCarthy more work than directing a handful of episodes for 13 Reasons Why and creating Alaska Daily. I’ll always be looking for the next McCarthy project when I can.

McCarthy’s movie acclimates the viewer to the simple charms of its people and the small town, getting to know the various characters and their foibles and hopes, getting used to the rhythms of this life and adjusting much like Fin. There are small victories that are payoffs, like Fin finally getting a library card, or speaking in front of a school class about his affinity for trains. It works so well. McCarthy continued his found family writing with 2007’s The Visitor and 2011’s Win Win, both anchored by the emotional enormity of sad, lonely men learning to open up to companionship. There were some dips in the road but McCarthy worked his found family magic to the biggest stage with 2015’s Best Picture winner, Spotlight, which McCarthy directed and co-wrote. His only follow-up theatrical movie was 2021’s Stillwater, where an oil rig dad (Matt Damon) tries to save his daughter overseas from a very ripped-from-the-headlines scandal (Amanda Knox was very unhappy). There is also a 2020 Disney Plus movie about a kid detective and his imaginary polar bear best friend (that actually sounds adorable). I guess I figured a Best Picture Oscar on your resume, as well as a history of working within the studio system and world of indies, would have given McCarthy more work than directing a handful of episodes for 13 Reasons Why and creating Alaska Daily. I’ll always be looking for the next McCarthy project when I can.

McCarthy’s failures can be just as intriguing as his successes. The Cobbler is just such an astounding idea that it’s hard to imagine anyone thinking it would work out, with Adam Sandler as a magic shoe-maker. However, this same pessimistic mentality probably prevailed when McCarthy was trying to raise money for The Station Agent. His indie successes proved that he could take any jumble of strange characters and turn it into a functional movie. Maybe that hubris, well-earned along with his contributions to the Oscar-nominated Up script, finally caught up with 2014’s The Cobbler. I would pay good money to one day watch that un-aired footage of the original Thrones pilot, the one the producers themselves acknowledged to be deeply troubled. After retooling the show and cast, bringing in Michelle Fairley and Emilia Clarke, McCarthy departed, though is credited for helping to secure Dinklage’s involvement, and it’s impossible to think of the zeitgeist-defining excellence of the HBO series with anyone else playing the iconic role of Tyrion Lannister.

Re-evaluating The Station Agent twenty years hence, its many charms are still abundant and I appreciated how gentle and relaxed everything felt. When indie movies deal with heavy amounts of quirk and oddities, it can often be heavy-handed and abrasive, never letting the audience forget for a second just how special and strange and different the movie must be (here comes 2024’s look at Napoleon Dynamite). McCarthy’s movie almost feels like a writing exercise where he plucked three very different characters out of a hat and challenged himself to build a grounded movie built upon their unexpected friendships. It’s a movie confident to just let the characters speak for themselves. It’s more a slice-of-life glimpse at people who feel far more real than most Sundance indies built upon oddballs and quirk. I would slightly lower the grade from an A to an A minus simply because of the Olivia character. Clarkson is great but her role feels undeveloped, somewhat redundant, and a little sloppy. Still, the enjoyable performances, the observational detail, and the simple pleasures of a story well told with characters you genuinely care about are what shines through even twenty years later.

Re-evaluating The Station Agent twenty years hence, its many charms are still abundant and I appreciated how gentle and relaxed everything felt. When indie movies deal with heavy amounts of quirk and oddities, it can often be heavy-handed and abrasive, never letting the audience forget for a second just how special and strange and different the movie must be (here comes 2024’s look at Napoleon Dynamite). McCarthy’s movie almost feels like a writing exercise where he plucked three very different characters out of a hat and challenged himself to build a grounded movie built upon their unexpected friendships. It’s a movie confident to just let the characters speak for themselves. It’s more a slice-of-life glimpse at people who feel far more real than most Sundance indies built upon oddballs and quirk. I would slightly lower the grade from an A to an A minus simply because of the Olivia character. Clarkson is great but her role feels undeveloped, somewhat redundant, and a little sloppy. Still, the enjoyable performances, the observational detail, and the simple pleasures of a story well told with characters you genuinely care about are what shines through even twenty years later.

Author’s note: In my original review, I cite having interviewed Michelle Williams (yes, surprise, she plays the small-town librarian). While I was my college newspaper’s film critic from January 2002 to May 2004, I did have the opportunity to interview several actors and directors through phone cattle calls with other collegiate journalists. These names include Angelina Jolie (Tomb Raider 2), Billy Bob Thornton (Bad Santa), Kevin Smith (Jersey Girl), and the late Paul Walker (Timeline). However, my school schedule was not accommodating for the Williams interview, so I had my dormitory neighbor and friend Tim Knopp call in and ask my question. It wasn’t me. I’m coming clean after twenty years, folks. I also recall having him quote a line her character says in The Station Agent, saying Fin had “a nice chin,” and being told that she was baffled and blanking on the reference. I’m sorry, eventual multi-Oscar nominee Michelle Williams, for trying to be clever.

Re-View Grade: A-

Emily the Criminal (2022)

This Sundance indie thriller packs more anxiety into 90 minutes than most Hollywood thrillers combined. It’s a starring vehicle for Aubrey Plaza as the titular Emily, a woman with a prior criminal record who finds herself in debt and struggling to find a better paying job. In desperation, she joins a small-time credit card fraud squad, using stolen identities to purchase expensive electronics and pass along to her employer to resell. At first, it’s a quick and easy fix and she can walk away at any time, but the money is good and Emily begins to take on bigger and riskier jobs. It’s here where I really started sweating as Emily gets into some very serious jams, but she comes back swinging, and it’s a thrill. At the same time, you worry that she’s going too far and there may be no turning back. The movie reminded me a lot of 2016’s Good Time, an electric indie thriller that vibrated with anxiety as well as a surprising but thoughtful cause-effect story flow. Emily the Criminal begins as an indictment on the social mechanisms that trap the poor into poverty but then in its second half escalates urgently, spiraling into a tragic confluence of violence and vengeance. Plaza is outstanding from the first scene onward. Even her posture speaks volumes about her character. It’s a performance where you can see the gears of her decision-making, whether it’s fight-or-flight impulses, swallowing her pride, holding to a façade, or regaining what has been taken from her. The very ending of the movie is perfect and a fitting end of Emily’s character arc. It’s the American Dream turned into a modern nightmare of perfectly perpetual desperation.

Nate’s Grade: A-

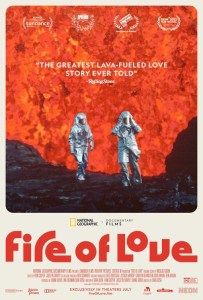

Fire of Love (2022)