Blog Archives

Anatomy of a Fall (2023)

I was so looking forward to watching the French drama Anatomy of a Fall, nominated for five Oscars including Best Picture and Best Director for Justine Triet, that I had to track down the publicity department for Neon Studios and hound them to finally get my annual Neon screener box-set for critics. It took several weeks, and email chains, but thankfully the good folks at Neon supplied me with their screener box, like Christmas morning for a film critic. The surprise Oscar nominations only made me more eager to finally watch this movie. As Anatomy of a Fall played, and the criminal case became ever more complicated, shedding further light upon the characters and their stormy marriage, I found myself sitting closer and closer to my TV, finally sitting on the floor right in front of it. Part of this can be explained by trying to better read the subtitles, though truthfully half of the movie is in English, but the real reason was that I became absorbed, waiting anxiously to see where it could go next, what twist and turn would further reassess our fragile understanding of the events, the people, and the possible circumstances. The original screenplay is so thoroughly engaging, and with supremely talented acting and clever directing, that I knew I was in good hands to ensure my investment of 140 minutes wouldn’t be wasted.

Popular novelist Sandra Voyter (Sandra Huller) is talking with a female reporter about her process as they lounge in her home. They’re drinking, laughing, and then the loud sounds of a steel drum start echoing from upstairs, thanks to Sandra’s husband, Samuel (Samuel Maleski), who puts the song on repeat. He’s passive aggressively sabotaging the interview, and Sandra bids goodbye to the interviewer. Hours later Samuel is found on the ground outside with blood seeping from a head wound. The attic window is open, the same attic he was remodeling before presumably falling to his death. Did he take his own life or was foul play involved? Did Sandra actually kill her husband?

At its core, the movie is an anatomy of a criminal investigation, a prosecution and the personal defense, but it’s really an anatomy of people and the versions of themselves that they selectively present to others and themselves. It’s an old maxim that you can never know what’s going on inside a marriage, or really any relationship, as the inner reality is far more complex than what is easy to digest and categorize by the public. It’s not new to hide aspects of ourselves from wider scrutiny and consumption. It also isn’t new for a larger public profile to invite speculation from online busybodies who think they are entitled to know more. The mystery about whether or not Sandra is guilty or a cruel victim of suspicious circumstance is a question that Triet values, but clearly she values other more personal mysteries more, chiefly the mystery of our understanding of people and why they may choose to do inexplicable acts. How close can we ever really know a person? The upending of her life pushes Sandra to re-examine her own marriage in such a high stakes crucible that can determine whether or not she spends the rest of her life in jail. Under those extreme circumstances, the bigger question isn’t how someone may have committed murder, or taken their life, but the unexamined why of it all that nibbles away at Sandra as well as our collective consciousness as viewers. To me, that’s a more compelling and worthwhile mystery to explore than whether or not it was a murder or suicide (there is a wild theory finding some traction online blaming the death on the family dog).

I don’t feel it’s a significant spoiler to prepare the viewer to know that Triet keeps to ambiguity to the bitter end, refusing to specify what actually happened to Samuel. It’s ultimately up to the viewer to determine whether they think Sandra is guilty or innocent, and there’s enough room to have a debate with your friends and Francophile colleagues. I’ll profess that I found myself on the Team Sandra bandwagon and fully believed she was being railroaded by the French judicial system and press. The righteous anger I felt on behalf of this woman rose to volcanic levels, as it felt like much of the French prosecution’s line of questioning and theorizing was mired in blatant eye-rolling misogyny and conjecture. They insist that because Sandra is bisexual that she must have been flirting with her female interviewer on the day of Samuel’s death, because that’s how it works for bisexuals, obviously, to only be able to size every person they meet, no matter whatever anodyne circumstances, as some possible or inevitable sexual conquest. As an outsider to the French judicial system, I was intrigued just by how the trials are conducted, which seems far less formal despite the wigs and robes, where the accused can interrupt anytime to deliver speeches and question experts. I also appreciated how much attention Sandra’s family friend and defense attorney puts into helping her shape her image, to the press, to the court, to the judge, down to her perspective of her marriage to her vocabulary choices. Rather than be a reflection of Sandra as coolly calculated, I viewed it as learning to prepare for the dangers ahead. It reminded me of Gone Girl with the media-savvy lawyer coaching his high-profile client through their trouble.

Of course, there are larger implications with this prosecution. Sandra isn’t just on trial for suspicion of killing her husband to clear the way for her next lover, she’s the victim of all the ways that women are judged and found guilty by society. Sandra is a successful novelist, the top provider, and her husband isn’t, and it eats away at him, festering resentment that she is somehow stifling his own creative dreams. Is she giving him space or being distant? Is she doing enough or too little? Is she a supportive spouse or selfish? Is she a good mom or a bad mom? Is she allowed an independent life or should she be fully devoted to the titles of mom and wife? It’s the struggle to fit into everyone’s impossible and conflicting definition of what makes an acceptable woman and mother, and it’s infuriating to watch (think America Ferrera’s Barbie speech but as a movie). It’s also an indication of the cultural true crime obsession and turning people’s complicated identities and nuanced relationships into easy-to-digest fodder for morbid entertainment. It’s not like there’s some grand speech that positions Sandra as the martyr for all of embattled womanhood, but through her trial and media scrutiny, these social issues are projected onto her like a case study.

As much as I loved Lily Gladstone and Emma Stone in their respective performances in 2023, at this point I’d gladly give the Best Actress Oscar to Huller (The Zone of Interest). First off, she delivers a tremendous performance in three separate languages, as her character is a native German who marries a Frenchman and then they agree to speak in English as their linguistic “middle ground,” a language that isn’t native to either of them. Huller slips into her character seamlessly and it’s thrilling to watch her assert herself, press against the bad faith assumptions of others. One of the highlights of the movie is the most extended flashback where we witness the simmering resentment of this marriage come fully to force, and while it’s unclear whether this moment, as the other occasional flashbacks, is meant to be conveyed as Sandra’s subjective memory or objective reality, it serves as a mini-climax for the story. It’s here where Sandra pushes back against her husband’s self-pitying criticisms and projections. It’s a well-written, highly satisfying “Amen, sister” moment, and Huller crushes it and him. There were moments where I was in awe of Huller that I had to simply whistle to myself and remark how this woman is really good at acting. With such juicy material and layers to sift through, Huller astounds.

Another actor worth celebrating is Milo Machado-Graner (Waiting for Bojangles) as the couple’s only child Daniel, a young boy who is partially blind because of an earlier accident from Samuel’s negligence and the one who discovers his dad’s body. This kid becomes our entry point into the history of this marriage but it also turns on his perceptions of his parents, as Sandra is worried over the course of the trial that Daniel will learn aspects of their marriage that she was trying to shield from him, and he may never be able to see his father and mother the same way again. It’s a rude awakening for him, and key parts of the trial rest upon a child’s shaky memory, adding intense pressure onto a hurting little boy. There’s a key flashback that will change the direction of the case, but again Triet doesn’t specify whether this is Daniel’s memory, Daniel’s distorted memory looking for answers whereupon there might not be any, or the objective reality of what happened and what was said. Machado-Graner delivers a performance that is built upon such fragility that my heart sank for him. It’s a far more natural performance free of histrionics and easy exaggerations, making the response to such trying events all the more devastating.

Anatomy of a Fall was not selected by its home country for consideration for the Academy’s Best International Film competition despite winning the Palme D’Or, the top prize, at the prestigious Cannes Film Festival. Not to take anything away from 2023’s The Taste of Things, a French drama I’ve heard only fabulous responses, but clearly they picked the wrong contender and lost a winnable race. Do you know the last time France won the Oscar for Best Foreign/International Film? You have to go all the way back to 1991’s Indochine, a movie about the history of France’s colonial occupation of Vietnam. For a nation known for its rich history of cinema, it’s now been over thirty years since one of their own movies won the top international prize at the Academy. Oh well, there’s always next year, France. It’s truly befuddling because Anatomy of a Fall is such an easily accessible movie that draws you in and reveals itself with more tantalizing questions. It has supremely accomplished acting, directing, and writing. Anatomy of a Fall is a spellbinding, twisty movie and one of the absolute best films of 2023, in any language.

Nate’s Grade: A

Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

Killers of the Flower Moon has the banner of an Important Movie, telling a story many history books have overlooked for too long, an American tragedy built upon one of America’s original sins with the indigenous peoples, and tying a direct line to not only how we live now as well as how we choose to remember the past. The true story behind the murder of the Osage Nation natives in the 1920s is an urgent story that gets to the heart of greed and the human capacity for evil, and Martin Scorsese’s three-and-a-half-hour movie is somber and mournful and appropriately devastating. But I’m also wondering why I wasn’t as enchanted with it as a movie-going experience. Should I feel movie critic guilt for finding the movie merely good but not transcendentally great?

The whole of Killers of the Flower Moon is bleak, which is naturally much of the point. It’s difficult to retell the history of Native Americans in this country, or before there was a “this country,” without making use of lots of synonyms for the word “bleak.” The first hour presents the Native Americans as being legally incapable of greater agency; the murders are consistent, sloppy, and obvious, but the fact that no investigation was triggered for years in an acknowledgement that, simply put, the government just didn’t care about dead Indians. Oh, I hear you saying, but weren’t these Osage different? They had so much money from their oil rights that the local economy exploded with vultures offering common services for egregiously inflated prices to take advantage of people unaccustomed to having money and options. Even with a surge of riches, the Osage didn’t have an elevation in status. They were still looked upon as interlopers in the way of powerful white men getting that money, and there’s nothing these greedy people won’t do to get that money, especially with a system of justice of little accountability for dead minorities. One of the more galling scenes is when the town coroners are questioned over their unusual protocols, like chopping a corpse into tiny pieces so it could not be re-examined by other professionals. The whole town is in on this vile scheme, every doting neighbor can be guilty through complicity or complacency. Death after death, they all know what’s really going on; it’s plain as day, but nobody outside of the Osage feels the burning outrage, and that’s the point of the first half of the movie, to give the audience the same sense of anger and futility.

The majority of the lengthy movie follows our villains plotting their very obvious conspiracy, with Leonardo DiCaprio badly clenching his jaw in every scene as Ernest Burkhart, a WWI-veteran who comes home, becomes a cabbie, and marries Mollie (Lily Gladstone), one of the rich local Osage women. The question for the rest of the movie is whether or not his love for her is genuine or perhaps she is just a means to an end. He’s the lead of the movie and a total dope, a man who unironically proclaims repeatedly, “I love me some money!” Seems hard to read this guy, right? He’s an idiot, and again this might be the point, that this sort of small-thinking man could be the hinge on this entire conspiracy, which results in a lot of Mollie’s family members dying under increasingly mysterious circumstances to consolidate their inheritance. It’s a frustrating and spiritually exhausting experience to watch all these poor characters get murdered, again, so casually and transparently. One of them is staged as a would-be suicide except he’s shot through the back of the head and the gun wasn’t left at the scene. Eventually, the FBI does finally (finally!) arrive in town at the two-hour mark, but by then, I’ve been watching two hours of people dying without a legal stir.

This perspective is best embodied through Mollie, beautifully played by Gladstone (Certain Women, First Cow). When we first meet her, she’s a forward woman who can assert herself and what she wants. Then it all goes downhill after marrying Ernest. She loses damn near every family member she has and is forced to rely upon her husband for support, the same idiot bungling his way through arranging the deaths of her family members. She’s a personal stand-in for the Osage Nation as a whole, as we watch what they have whittled down and bled dry, watching the weight of all this suffering deteriorate their spirits and dignity. This is Mollie, our avatar for tragedy. She’s literally bedridden for a solid hour, and I dearly missed Gladstone’s presence. Since we’ve been aware of the bad deeds of the bad men from the start, much of Killers of the Flower Moon becomes a waiting game of when Mollie is hopefully going to wise up or at least suspect what is happening to her and her family. When will she see Ernest as a more nefarious force in her life, the kind of person you don’t want to solely trust with the responsibility of delivering your life-saving intravenous medicine. It adds to the overall frustrations of watching. Gladstone’s performance rises above whatever limitations her character is stricken with. First off, it’s a powerful performance of immense sorrow; having to watch her pained reaction to overhearing her sister’s skull sawed open for a disrespectful public autopsy is just sickening. The movie lives off this woman’s response to unfathomable trauma on repeat. When she is bedridden and lost in a medical fog, she still manages to communicate her wariness and suspicion through these extra layers of obfuscation.

Robert DeNiro, appearing in his eleventh Scorsese movie, is terrifying as a kindly cattle baron who fashions himself as the best friend of the Osage, preferring to refer to them by their indigenous names and warmly speaking their language. He’s also a monster, a stand-in for American big business and the blood-stained hands of capitalism without morals and oversight. The dramatic core of the movie, besides how far will this go before consequences will at long last germinate, is how can such self-styled men of God commit such heinous acts? How can people justify and equivocate over their own cruel crimes? This question is epitomized in Ernest and his direct connection to Mollie, but it’s also epitomized through DeNiro’s character, William Hale. We have two characters fulfilling the same thematic purpose, which might be the point, but it makes for a redundant narrative experience. DeNiro’s character is so much more interesting than Ernest too, with the full cognitive dissonance of being an avowed man of the people and true ally to the Osage while he’s plotting their demise. DeNiro holds to this homespun, Foghorn Leghorn accent throughout, and I can’t recall him ever raising his voice. It’s a performance where the lasting terror comes through its friendly disconnect. It’s a more impressive performance than watching DiCaprio grimace and mumble through three and a half hours.

Some chastise Killers of the Flower Moon for choosing to tell its story from the perspective of its white perpetrators. I understand from a narrative standpoint and an overall larger thematic point why this was done. Scorsese clearly thinks of his own limits of being the one to tell this story, appearing as a cameo in the coda to provide commentary on how the American morbid desire for true crime and historical atrocities will lead to yesterday’s outrages becoming today’s distilled and de-contextualized “content.” The problem is the movie already feels frustrating as is while we wait for there to finally be some accounting for the ongoing injustices, and centering the entire perspective on only the Osage would magnify this frustration with even less elucidation on the depths of what was happening. Scorsese strips away a lot of the stylistic flourishes and even the electric pacing and editing that we come to expect from his filmography. This is a slow, ponderous movie. It’s meant to provoke outrage. It’s also designed to frustrate, and I suppose I can admire that while also impatiently shifting in my seat and wondering how many of these 206 minutes could have been lost. I feel like a philistine for looking at a $200-million Scorsese movie, while this man is in the late stages of his career and clearly thinking of this reality, and asking, “Hey, can you give me maybe less movie?”

If you haven’t noticed, dear reader, I am a critic in conflict. Killers of the Flower Moon has fantastic production values, strong acting, and the importance of staging history as it was rather than how it may be remembered, especially over events long ignored by history. I even admire the choices that are deliberate that make the movie feel less like easily consumed entertainment. It’s a movie that I feel compelled to see a second time before I settle on my eventual rating (a seven-hour commitment). It’s a sad movie, a bleak movie, a challenging movie, a meaningful movie, and an Important Movie about Important Things. It’s also long, frustrating in structure and execution, and occasionally redundant with its characterization and plotting, giving the impression that things have been stretched beyond breaking. Again, maybe that’s the larger thematic point, but then again I might just be stuck in a rabbit hole of excuses to find some justification for my less-than-ecstatic reaction to Killers of the Flower Moon, a movie of strident artistic vision that can also feel like you’re eating your vegetables for three nonplussed hours.

Nate’s Grade: B

Poor Things (2023)

Poor Things is going to be a lot to many people. It is a lot, and that’s kind of the larger message because ultimately, for all its peculiarities and perversions, the movie is also an inspiring fable about living one’s life to the fullest and embracing the choices that make us happy and content. It’s a feminist Frankenstein allegory as well as an invitation to see the world with new eyes and a fresh perspective, to embrace the same hunger for a life that defines the journey of Bella Baxter from woman to child to woman again. Under the unique care of director Yorgos Lanthimos and screenwriter Terry McNamara (reuniting after 2018’s triumphant and irreverent The Favourite), Poor Things proves to be an invigorating drama, a hilarious comedy, a stunning visual experience, and one of the year’s finest films.

Poor Things is going to be a lot to many people. It is a lot, and that’s kind of the larger message because ultimately, for all its peculiarities and perversions, the movie is also an inspiring fable about living one’s life to the fullest and embracing the choices that make us happy and content. It’s a feminist Frankenstein allegory as well as an invitation to see the world with new eyes and a fresh perspective, to embrace the same hunger for a life that defines the journey of Bella Baxter from woman to child to woman again. Under the unique care of director Yorgos Lanthimos and screenwriter Terry McNamara (reuniting after 2018’s triumphant and irreverent The Favourite), Poor Things proves to be an invigorating drama, a hilarious comedy, a stunning visual experience, and one of the year’s finest films.

Bella (Emma Stone) lives a life of solitude with her caregiver, a brilliant but disfigured surgeon named Dr. Godwin Baxter (Willem Defoe), who Bella refers to as “God,” and for good reason. Bella is herself one of the doctor’s experiments. Her body belongs to an adult woman of a different name who killed herself. Her mind belongs to the baby that had lived through its mother’s suicide. “God” resuscitated the body of the mother by giving her the brain of her child. She’s curious and defiant and soon yearns for independence and discovering the outside world. A caddish lawyer, Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), is drawn to Bella and offers to take her on a grand adventure to parts of the world. She agrees, and from there Bella gets an education on the plentiful pleasures and pains and puzzles of being a human being. In many ways, Poor Things serves as a fish-out-of-water fairy tale that invites the audience to question and analyze the Way Things Are. Bella’s childlike perspective allows her to strip away the assumptions of adulthood and the cynicism of disappointment. Everything is new and potentially exciting, but she can also cut through the cultural hang-ups and repressive rules of polite Victorian society. This is expressed perhaps most memorably in her embrace of sexuality and the pursuit of physical pleasure. She’s told not to seek out this pleasure except for very specific settings and situations, and this confounds her. Why aren’t people doing this all the time, she asks after an extensive session of vigorous sexual activity. She is a person incapable of shame during a modest time of conditioned shame. This brashly hedonistic reality might prove too morally demented for many viewers uncomfortable with the premise. In context, it is a grown woman’s body being operated by the mind of a child. We are told that she grows and matures as she accumulates her worldly experiences, but the movie keeps it purposely vague how analogous her brain-age might be and whether that maturation is of a pace with traditional aging. It’s a reverse of 1979’s The Tin Drum, a German movie where a child refuses to grow up once he hears the drudgery of the adult world, and so he remains three years old in appearance but continues maturing intellectually and emotionally. There’s a cliche about looking at the world with a child’s unassuming eyes, and that doesn’t necessarily mean only looking at the things that are safe and appropriate for children.

In many ways, Poor Things serves as a fish-out-of-water fairy tale that invites the audience to question and analyze the Way Things Are. Bella’s childlike perspective allows her to strip away the assumptions of adulthood and the cynicism of disappointment. Everything is new and potentially exciting, but she can also cut through the cultural hang-ups and repressive rules of polite Victorian society. This is expressed perhaps most memorably in her embrace of sexuality and the pursuit of physical pleasure. She’s told not to seek out this pleasure except for very specific settings and situations, and this confounds her. Why aren’t people doing this all the time, she asks after an extensive session of vigorous sexual activity. She is a person incapable of shame during a modest time of conditioned shame. This brashly hedonistic reality might prove too morally demented for many viewers uncomfortable with the premise. In context, it is a grown woman’s body being operated by the mind of a child. We are told that she grows and matures as she accumulates her worldly experiences, but the movie keeps it purposely vague how analogous her brain-age might be and whether that maturation is of a pace with traditional aging. It’s a reverse of 1979’s The Tin Drum, a German movie where a child refuses to grow up once he hears the drudgery of the adult world, and so he remains three years old in appearance but continues maturing intellectually and emotionally. There’s a cliche about looking at the world with a child’s unassuming eyes, and that doesn’t necessarily mean only looking at the things that are safe and appropriate for children.

Bella responds with wonder to the many pleasures of being human, but, sadly, it’s not all puff pastries and orgasms. The world is also filled with horrors and injustices, and Bella’s personal journey of discovery is also one discovering the human capacity for cruelty and selfishness. Some of this is a response to Bella wanting to assert herself and independence, as she very reasonably doesn’t understand why all these men get to tell her what to do or expect that they should. At one point, Duncan literally hurls her books into the sea so that she will not continue educating herself. This extends to later in the movie when Bella looks at prostitution in a Parisian brothel as a means of earning a living. Her same sexual appetites, that were enthusiastically encouraged by Duncan, are now paradoxically looked at by the same man as wicked. Absent riches, Bella is treated as a disposable commodity and she’s trying to make sense of why one version of her receives respect and adoration and another version is looked with disgust. It seems that an essential part of maturation is acknowledging the faults of this world and its entrenched systems of thought, but does giving in to these systems make one more human or merely more cynical? Is it a matter of learning or is it a matter of giving up on changing the status quo? These are many of the questions that the movie inspires as we join Bella on her fantastic journey of self-discovery. This movie would not work nearly as well without the fearless performance from Stone (Cruella). She gives everything of herself for this role and rewires the very movements of her body to better portray such a unique elding of a character at so many crossroads. Her early physicality is gangly like she’s learning how to operate this adult body of hers that appears too ungainly, and her expressions are without restraint, as if she’s peeled back every acting impulse to instead find a purity of perception. There is a transparent and transcendent joy in her performance as well as an ache when Bella discovers the awful shortcomings of this world. Lanthimos movies exist in a different world than ours, a cracked mirror universe of deadpan detachment and casual cruelty, so it requires a commitment to a very specific tone of performance. And yet, the requirements of this role work against that Lanthimos model of acting because Bella cannot be detached from this world. As a result, there is the same matter-of-fact reaction to the world but channeled through an idealistic innocence rather than the sarcastic skepticism that can dominate the director’s oeuvre.

This movie would not work nearly as well without the fearless performance from Stone (Cruella). She gives everything of herself for this role and rewires the very movements of her body to better portray such a unique elding of a character at so many crossroads. Her early physicality is gangly like she’s learning how to operate this adult body of hers that appears too ungainly, and her expressions are without restraint, as if she’s peeled back every acting impulse to instead find a purity of perception. There is a transparent and transcendent joy in her performance as well as an ache when Bella discovers the awful shortcomings of this world. Lanthimos movies exist in a different world than ours, a cracked mirror universe of deadpan detachment and casual cruelty, so it requires a commitment to a very specific tone of performance. And yet, the requirements of this role work against that Lanthimos model of acting because Bella cannot be detached from this world. As a result, there is the same matter-of-fact reaction to the world but channeled through an idealistic innocence rather than the sarcastic skepticism that can dominate the director’s oeuvre.

The supporting cast contributes wonderfully. Dafoe (The Lighthouse) is a natural at being a weirdo, but he exhibits a paternal love for his creation that is surprisingly earnest. I laughed every time he went into one of his extended wails when he was disconnecting himself from a machine to handle his bodily gasses. Ruffalo (The Adam Project) is devilishly amusing as he abandons all pretense of likeability to play a deeply manipulative but fascinating louse, a character that is almost as transparent about his desires as Bella. His faux elitism is a constant source of comedy. Kathryn Hunter (The Tragedy of Macbeth) has a memorable and sinister turn as the brothel madame who teaches Bella about the nature of capitalism and socialism. Christopher Abbott (Black Bear) appears late as a privileged man from Bella’s past reappearing with his own demands, and his is the most terrifying portrait in the entire wacky movie, an antagonist that’s all too real and scary in a movie given to such brilliantly quixotic flights of fancy.  Under Lanthimos’ direction, the movie presents the world as an awesome discovery and the lurches into the surreal allow the viewers to see the marvels of existence with the same awe as Bella. The movie feels like it takes place in a science fiction universe of crazy visuals and the avant garde incorporation of past, present, and future. It makes every scene something to behold. This is his most visually decadent film of his career. The musical score by Jerskin Fendrix, a first-time film composer, and it works on a thematic level as trying to discover new kinds of sounds along with the journey of its heroine. However, there are sequences where the music feels like an assault on your ears. While intentional, the detours into abrasive dissonance can make one long for something less experimental and more traditional at least for the sake of your own sensitive eardrums.

Under Lanthimos’ direction, the movie presents the world as an awesome discovery and the lurches into the surreal allow the viewers to see the marvels of existence with the same awe as Bella. The movie feels like it takes place in a science fiction universe of crazy visuals and the avant garde incorporation of past, present, and future. It makes every scene something to behold. This is his most visually decadent film of his career. The musical score by Jerskin Fendrix, a first-time film composer, and it works on a thematic level as trying to discover new kinds of sounds along with the journey of its heroine. However, there are sequences where the music feels like an assault on your ears. While intentional, the detours into abrasive dissonance can make one long for something less experimental and more traditional at least for the sake of your own sensitive eardrums.

Life can be decadent, it can be confusing, it can be ridiculous, it can be heartbreaking, it can be terrifying, but it’s an experience worth savoring and embracing, and this ultimately is the message of Poor Things. Stone is brilliant as she confidently carries us along for every moment of an exploration of what it means to be human, and with an ending that is so fitting and satisfying that I wanted to stand and applaud. For those squeamish from the heavy amounts of sexuality, Poor Things is at its core a very pro-life movie. It’s an inspiration to make you think one minute while making you snort laughing the next. May we all see the world with the voracious hunger and curiosity and boldness of Bella Baxter with her second chance at this one life.

Nate’s Grade: A

The Zone of Interest (2023)

The Zone of Interest is one of the more maddening film experiences I’ve ever had, and I’m sure that was part of the intention of writer/director Jonathan Glazer (Under the Skin). While based upon a 2014 fictional book by Martin Amis, Glazer had hollowed out the novel’s fake story and replaced it with its inspiration, the Höss family, a real-life German couple and their children who literally had their villa next door to the horrendous Auschwitz concentration camp. The husband was the chief commandant for the camp, and he had his family literally sharing wall space with the notorious factory of death. The entire feature film is then given to observing this family from afar as they try to live a “normal domestic life” in the shadow of something profoundly abnormal and abhorrent. It’s a classic example of a type of movie I will dub the “Yeah, okay, so what?” movie. I get it, I do, but why is this exactly a feature film?

I understand artistically what Glazer is going for here. It’s the ironic juxtaposition of the ordinary and the awful, asking the viewer to think about how many millions of Germans went along with the mounting anti-Semitic and racist policies of Nazi Germany out of self-interest and/or willful ignorance, the banality of evil, as Hannah Arendt termed it. That becomes the challenge of the movie, watching this family tend to the garden, host a birthday party, and read bedtime stories while watching the gloom of the chimneys, listening to the constant soundtrack of scattered gunshots and the screams of victims, including the wails of babies. Every scene is elevated by the dramatic irony of the context that it is happening next door to a concentration camp. We watch them plant flowers, and it just so happens to be next door to a concentration camp. We watch them invite the mother-in-law to make her new bedroom her own, and it just so happens to be next door to a concentration camp. It gets tedious as a viewer because without the irony, we’re just watching a family live their life. I get that’s the point, this example of one family trying to ignore the terrifying reality literally at their very doorstep. I understand that message and I understand why that is even more relevant to our troubled modern times with an alarming rise in anti-Semitism and the celebration of fascism and repressive strongmen. However, I don’t think we get real insights into these characters because they’re more just general ideas intended to forward the critical thesis of the power of self-delusion and excuse-making. That’s fine as a starting point for a provocative movie, but don’t make me watch a family do their laundry for an hour and then tell me it’s an Important Statement because they happen to be next door to the horrors of history.

Let me try this same kind of approach on another human tragedy. Say we have a family drama about a hard-working couple trying to go through the day-to-day challenges of marriage and raising a family, and it JUST SO HAPPENS that they live within distance of… the internment of the Japanese in World War II. Does this magically transform and elevate the ordinary actions on-screen into more than what they are? Perhaps to some, but for me it felt too transparently methodical and quickly redundant. I don’t need a whole movie documenting a family next door that barely scratches the surface of their circumstances of living.

There are a few moments that manage to break through. There’s a scene where the daughters are swimming in the nearby river and the family realizes that the gray streams intruding upon the water are the ashes from the camp. From there they furiously scrub themselves clean, the grotesque horror something they attempt to cleanse, whether they’re horrified because the ash belongs to people or because it specifically belongs to Jews. The mother (Sandra Huller) refuses to move away after her husband Rudolph (Christian Friedel) is reassigned by the Nazi brass. This is the home she’s put her time into remodeling and reshaping and she isn’t going to just let anyone live under her roof. This setback is far more upsetting to her than anything she overhears on the other side of her garden walls. There’s also an ongoing story where one of the Höss children is leaving behind a trail of apples, inspired by a favorite bedtime fable, and this has an unfortunate unintended tragedy for people these children will never know or see. There’s an offhand remark by the mother-in-law as she’s touring the backyard where she wonders if a woman in her book club is among the throng next door in the camps. Rather than use this as a moment of reflection over the genocide occurring next door, she then moves onto lamenting that she never got this same woman’s curtains that she always prized. I wish the movie had more of these character moments that directly confront the willful ignorance rather than keeping the audience simmering with the same meditative Big Picture concept that has been relentlessly winnowed down so finely that it may as well be dust.

Glazer makes very specific choices to highlight the detachment of the movie. His camera angles are often taken from far fixed points, and the coverage makes for smooth edits that let you know there were multiple cameras filming these scenes rather than the stress of multiple setups and different takes to cobble together. This makes the movie feel closer to a documentary where we have captured real life as it is happening instead of a group of actors on a set pretending to be different people putting on a show for our entertainment.

The Zone of Interest is a movie that crushes you in the everyday details, and in that it reminded me of 2020’s The Assistant, another indie that didn’t quite work for me. That film was about a young woman who served as a film production assistant to a producer modeled after Harvey Weinstein, and it asked how much she can ignore for the sake of her own upward mobility. It had a really compelling premise but the movie spent most of its running time just watching her do her job, filing papers, getting coffee, walking home, with the implicit knowledge banging around in our anxious minds to then elevate the mundane (she’s not just fixing the copy machine, she’s fixing the copy machine and Harvey Weinstein might be abusing someone just in the next room!). This ironic juxtaposition proved too tiring for me without also exploring the characters and conflicts more explicitly. Things happening off-screen while far more boring things happen on-screen is not itself great drama. Being drama-adjacent does not automatically magically imbue the ordinary with transcendent meaning. I need more than, “Big things are happening… over there.” The Zone of Interest is a critical favorite for 2023 but I think many viewers will have the same response I did: yeah, okay, so what?

Nate’s Grade: C+

Monster (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released December 24, 2003:

Originally released December 24, 2003:

Monster follows the life of Aileen Wuornos (Charlize Theron, now nominated for a Best Actress Oscar), Americas only known female serial killer. In the late 1980s, Wueros was a roadside prostitute flexing her muscles with Florida motorists. She describes hookin’ as the only things shes ever been good at. One day Wuornos has the full intention of taking her own life, but she meets 18-year-old Selby (Christina Ricci) at a lesbian bar and finds a companion. Driven by a growing hatred of men from sexual abuse, Wuorno’s starts killing her johns to try and establish a comfortable life for her and Selby.

Let’s not mince words; Theron gives one of the best performances I have ever seen in my life. Yes, that’s right. One of. The. Best. Performances. Ever. This is no exaggeration. I’m not just throwing out niceties. Theron is completely unrecognizable under a mass of facial prosthetics, 30 extra pounds, fake teeth and a total lack of eyebrows. But this is more than a hollow ploy to attract serious attention to the acting of a pretty face. Theron does more than simple imitation; she fully inhabits the skin of Aileen Wuornos. The closest comparison I can think of is Val Kilmer playing Jim Morrison in The Doors.

Theron is commanding, brave, distressing, ferocious, terrifying, brutal, stirring, mesmerizing and always captivating. It may be a cliché, but you really cannot take your eyes off of her. Her performance is that amazing. To say that Theron in Monster is an acting revelation is perhaps the understatement of the year.

With previous acting roles in Reindeer Games and The Cider House Rules, Theron is usually delegated to pretty girlfriend roles (who occasionally shows her breasts). Who in the world thought she had this kind of acting capability? I certainly did not. If Nicole Kidman can win an Oscar for putting on a fake nose and a so-so performance, surely Theron should win an Oscar for her absolute transformation of character and giving the performance of a lifetime.

With this being said, and most likely over said, Monster is by no means a perfect film. Minus the terrific central performance, Monster is more of an everyday profile of a grotesque personality. The film weakly tries to portray Wuornos more as a victim, but by the end of the film, and six murdered men later, sympathy is eradicated as Wuornos transforms into the titular monster. Some supporting characters, like Ricci’s narrow-minded Christian up bringers, are flat characters bordering on parody. The supporting characters are generally underwritten, especially the male roles that serve as mere cameos in a film dominated by sapphic love.

Monster is proof positive that human beings will never be phased out by advancing machinery when it comes to acting. Monster boasts one of the greatest acting achievements in recent cinematic history, but it also coasts on sharp cinematography and a moody and ambient score by BT (Go). Monster is a haunting film that you won’t want to blink for fear of taking your eyes off of Theron. She gives an unforgettable tour de force performance that will become legendary.

Nate’s Grade: B

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

Monster was a revelation for Charlize Theron, an actress who until then had mostly been known for parts that asked that she be good looking and little else. Twenty years later, Theron is one of the best actresses working in Hollywood and it almost never happened without her breakthrough performance where she brought to startling life the horror of Aileen Wuornos’s tragic life and tragic desperation. When this movie came out originally in 2003, I doubt anyone but Theron’s closest friends suspected she was capable of a performance this raw and spellbinding, but that’s also a condemnation on all of us. How many other actresses out there could maybe rival the best of the best if they just had the right opportunity? How many actresses are stuck playing the same limited roles because that’s all they’re ever asked to do? How many actresses are wrongly assumed to be of limited talent simply because of their comely appearance? That isn’t to say there’s some hidden universal equation that the uglier you are the better at acting you have to be (though it sure has worked out for [insert your example of a conventionally unattractive actor here]), but this movie is a clear indication that too many actors are never given enough opportunities to shine.

Back in early 2004, I credited Theron’s performance as one of the best I’ve ever witnessed in my then-twenty-one years of moviegoing (although that number should be smaller considering I wasn’t keenly watching Scorsese as a baby). She is very good, but I’d like to claw back some of my rapturous words of praise now that we’ve seen twenty years of Theron acting excellence. Looking over her career, I might actually cite 2011’s Young Adult as her finest performance, and that one didn’t even nab an Oscar nomination (she’s since been nominated twice since, for 2005’s North Country and 2019’s Bombshell). The draw of the movie is the head-turning performance from Theron and she just disappears completely inside the skin of her subject. It’s hard to remember at times that this is Theron, thanks to the richness of her startling performance but also the accomplished makeup effects, which were not nominated. At every point, you feel the fire burning behind the stricken complexion of Theron, a fire that will eventually consume her and everything she loves. While highly compelling, this is not a performance of subtlety and restraint. This is a big performance, and the movie is often prone to making loud pronouncements about its subjects and pertinent themes. It’s loud, brash, and maybe for some it will seem a little too loud, a little too unsubtle, but it’s a movie that refuses to be ignored for good reason.

In my original review I raised some reservations with the rest of the movie, and I’m here to recant one of them. I wrote back in 2004, “The film weakly tries to portray Wuornos more as a victim, but by the end of the film, and six murdered men later, sympathy is eradicated as Wuornos transforms into the titular monster.” I’m positive that many will still cling to this same idea but oh boy have I come around in twenty years. By the time the movie is over, you wonder why more women haven’t just snapped and gone on killing sprees. Wuornos is indeed a victim. She’s responsible for terrible deeds but that doesn’t change the fact that she started as a victim and continued as one until put to death by the state of Florida in 2002. She was a sexual assault survivor, groomed into prostitution, and then trapped by a society that saw her as little other than trash, something to be pitied but ultimately forgotten. She comes of age as an adult thinking her only value is the fleeting moments of pleasure she can provide for men, and in the narration, we hear her dreams that one of these men who repeatedly tell her how pretty she is would take her away to another life, like a princess. Alas. It’s impossible to separate her past as a victim of predatory men from her actions when she turns on predatory men. Being forced into prostitution out of desperation is one of the definitions for sex slavery and trafficking. The movie does try to make her last few johns more ambiguous over whether or not they are “good people” and thus “deserving” of their fates, like a scale is being introduced and we’re doing the calculation whether Wuornos will strike (#NotAllMen, eh felas?). There’s a clear dark path where the murders get considerably worse. She begins by defending herself against a rapist, but by the end, it’s just a kind family man who picked her up without even the intention of having sex. We’re meant to see her transform into the titular monster, but I kept wondering about Aileen Wuornos as the societal stand-in, accounting for thousands of other women who lived and died under similar tragic circumstances.

In my original review I raised some reservations with the rest of the movie, and I’m here to recant one of them. I wrote back in 2004, “The film weakly tries to portray Wuornos more as a victim, but by the end of the film, and six murdered men later, sympathy is eradicated as Wuornos transforms into the titular monster.” I’m positive that many will still cling to this same idea but oh boy have I come around in twenty years. By the time the movie is over, you wonder why more women haven’t just snapped and gone on killing sprees. Wuornos is indeed a victim. She’s responsible for terrible deeds but that doesn’t change the fact that she started as a victim and continued as one until put to death by the state of Florida in 2002. She was a sexual assault survivor, groomed into prostitution, and then trapped by a society that saw her as little other than trash, something to be pitied but ultimately forgotten. She comes of age as an adult thinking her only value is the fleeting moments of pleasure she can provide for men, and in the narration, we hear her dreams that one of these men who repeatedly tell her how pretty she is would take her away to another life, like a princess. Alas. It’s impossible to separate her past as a victim of predatory men from her actions when she turns on predatory men. Being forced into prostitution out of desperation is one of the definitions for sex slavery and trafficking. The movie does try to make her last few johns more ambiguous over whether or not they are “good people” and thus “deserving” of their fates, like a scale is being introduced and we’re doing the calculation whether Wuornos will strike (#NotAllMen, eh felas?). There’s a clear dark path where the murders get considerably worse. She begins by defending herself against a rapist, but by the end, it’s just a kind family man who picked her up without even the intention of having sex. We’re meant to see her transform into the titular monster, but I kept wondering about Aileen Wuornos as the societal stand-in, accounting for thousands of other women who lived and died under similar tragic circumstances.

I also found myself growing increasingly contemptuous of the love interest character played by Christina Ricci (Yellowjackets). When we’re introduced to Selby, she’s a wide-eyed naif testing her boundaries of comfort but clearly tapping into repressed homosexual feelings. Their relationship is meant to serve as the emotional rock for Wuornos, the reason that she’s acting more rash is because she’s trying to earn enough money for the two of them to run away together and build a new life. She is her motivation, but Selby is absolutely the worst. You can excuse some of her hemming and hawing about striking out on her own and leaving her controlling parents, as she’s fighting against repression as well as trepidation for starting out independently, but this lady becomes fully aware of the dangers and dehumanization that Aileen goes through to earn her meager amounts of money, and Selby encourages her to do so. Not just encourages her, Selby pressures her to do so, to get back out there and “provide” for her, knowing fully well what that means, knowing fully well how these men have treated Wournos, repeatedly abusing her. What are you doing to help things out, huh Selby? She’s embarrassed hanging around Wuornos around some other lesbian friends she just met, so she’s already looking to upgrade and move past her lover. By the end, as she’s trying to coax a confession of guilt from her girlfriend to save her own skin, Selby becomes just another user, taking what they want from Wuornos and discarding her when they’ve had their fill.

This was the directorial debut for Patty Jenkins, who also served as the sole credited screenwriter, and while the indie darling-to-franchise blockbuster pipeline has been alive and well in Hollywood, it was quite a surprising leap that her next movie after Monster was none other than 2017’s Wonder Woman. To go from this small character-driven true crime indie to leading the big screen solo outing for comics’ most famous female hero is quite a bizarre but impressive jump. Her only other feature credit is the much less heralded 2020 Wonder Woman sequel. She was attached to direct a Star Wars movie about fighter pilots but that seems to have gone into turnaround or just canceled. So is the way with Star Wars movies after 2019’s Rise of Skywalker. Just ask the Game of Thrones creators, Josh Trank, and Taika Watiti how that goes.

This was the directorial debut for Patty Jenkins, who also served as the sole credited screenwriter, and while the indie darling-to-franchise blockbuster pipeline has been alive and well in Hollywood, it was quite a surprising leap that her next movie after Monster was none other than 2017’s Wonder Woman. To go from this small character-driven true crime indie to leading the big screen solo outing for comics’ most famous female hero is quite a bizarre but impressive jump. Her only other feature credit is the much less heralded 2020 Wonder Woman sequel. She was attached to direct a Star Wars movie about fighter pilots but that seems to have gone into turnaround or just canceled. So is the way with Star Wars movies after 2019’s Rise of Skywalker. Just ask the Game of Thrones creators, Josh Trank, and Taika Watiti how that goes.

Monster is a phenomenal performance with a pretty okay movie wrapped around it in support. Twenty years later, Theron is still a monster you can’t take your eyes away from. It changed her career destiny and I think acts as an exemplar for two reasons: leaving the viewer with the question how many other wonderfully talented performers will never get the chance to showcase their true talents because of faulty assumptions, and how many other women are out there living in quiet degradation like Aileen Wuornos.

Re-Veiw Grade: B

May December (2023)

The critical darling May December reminded me of another 2023 Netflix prestige awards contender, David Fincher’s The Killer. That genre movie was about trying to tell a realistic version of the cool super spy assassin and I found that enterprise to be fitfully interesting but mostly dull and unfulfilled. This movie seems to be going for a similar artistic approach under director Todd Haynes (Carol, Far From Heaven), tackling a sensationalized ripped-from-the-tabloids tale of perversity but telling a more realistic version, which also leaves the movie fitfully interesting but mostly dull and unfulfilled. May December is a frustrating viewing experience because you easily recognize so much good, so many exciting or intriguing elements, but I came away wishing I had seen a different combination and execution.

Elizabeth (Natalie Portman) is a famous actress with an exciting new movie role. She’s going to play Gracie (Julianne Moore), a woman who gained national scandal for her sexual relationship with a then-13-year-old Joe. The two of them have been together for several decades and have several children and now are inviting Elizabeth into their home to better understand her character. Each person is on their guard. Elizabeth wants to keep prying to uncover emotional truths that she can gobble up to improve her future performance and career. Gracie is wary of making sure the version of her story that she wants for public media consumption is what Elizabeth receives. And Joe (Charles Melton), now in his mid-thirties and looking more like an older brother than father to his graduating children, is reflecting about the history of his relationship and who was culpable.

There’s so much here in the premise of an actress studying her subject and wreaking domestic havoc in her attempt to discover secret truths that would rather stay hidden. May December uses this premise as an investigative device, allowing the inquisitive actress to serve as the role of the audience, trying to form a cohesive vision of events from each new interview. It allows the first half of the movie to feel like a true-crime mystery, uncovering the different sides of a sordid story and the lasting consequences and legacy for so many. There’s a very lurid Single White Female approach you could go, where the avatar of the person starts to replace the real person, where Elizabeth crosses all sorts of lines and even thinks about crossing some of the same lines that Gracie had; what better way to get in the mind of a predator, right? I was waiting for this interloper to destabilize this carefully put-together illusion of a “normal family,” but by the end you feel like little has been learned and most everything reverts to its prior stasis. I suppose that’s, again, the more realistic version of this kind of story, that even when confronted with uncomfortable revelations most people will fall back on what they know. May December’s underwhelming conclusion is that, by the end, maybe people are actually who we think they are.

Haynes’ cinematic specialty is exploring the artificiality of movies, from having multiple actors portray Bob Dylan in 2007’s I’m Not There, to destabilizing the nostalgia of the 1950s Douglas Sirk-styled romantic drama with 2002’s Far From Heaven. He’s also inherently drawn to stories of emotional and sexual repression. This movie is all about performance as identity; it’s about an actress trying to refine her tools, but it’s also about a middle-aged woman who has adopted performance as her defense system (this also might explain why Gracie’s lisp seems to come and go). Some part of her has to know that she crossed some very serious lines, no matter how many times she explains away their relationship as merely “unconventional.” Even though they’ve kept this union for 25 or so years, it still began when Joe was 13 years old and she was an adult. There are very intriguing dimensions to this dramatic dynamic, with the excuse of a Hollywood version of their “love story” to motivate each participant to reflect with renewed perspective. The problem is that Gracie has worn her mask for so long that I doubt there is another version of her any longer (“I am naive. In a way, it’s a gift”). As a means of survival, she projects herself as a well-intentioned victim of scrutiny rather than as a child predator who has manipulated her husband into codependency for decades. This means that, frustratingly, there isn’t much there to glean once the facts of the case have been collected, which makes watching a bad TV actress try and better emulate a bad person incapable of introspection seem like an empty exercise in artistic masturbation, and maybe that’s the point?

The conversation around May December being some kind of “camp comedy” (it was recently nominated for Best Comedy/Musical by the Golden Globes) has left me genuinely stupefied. I think the term “camp” is used a little too loosely, as some seem to conflate any heightened emotion as equivalent to camp. May December is really more an example of melodrama. It’s near impossible to retell the Mary Kay Letourneau story without the use of melodrama, so its inclusion doesn’t merely qualify the movie as camp. But at the same time Haynes is making deliberate use of certain elements that make the movie even more jarring, like the oppressive and operatic musical stings that hearken to earlier 1950s melodramas. These musical intrusions are so broadly portentous that it’s practically like Haynes is elbowing you and saying, “Eh, eh?” I suppose you can laugh at how arch and over-the-top the musical stings are, but is this a comedic intention? Are we supposed to laugh at how out of place this musical arrangement is in modern filmmaking, or is Haynes trying to draw allusions to old Hollywood melodramas and make a case for this being similar? Whatever the case may be, I guess one could laugh at the stilted performances but then I think that’s approaching the movie from an ironic distance that makes it harder to emotionally engage, which seems like the whole point of the exercise, to go deeper than lazy tabloid summation.

The performances from the female leads circling and studying one another are rather heavy on mannered affectations and arch irony, but it’s Melton (TV’s Riverdale) who emerges as the soul of the movie. He’s so easy going and dutiful, quick to defend his wife and assure everyone that even at 13 years old he knew what he was doing and consented to their affair. Of course this is nonsense, and the real draw of the movie is watching this family man begin to crack, and when he does it’s like every repressed emotion comes spilling out. It makes you wish that he had been the main character of the story and Elizabeth more the supporting character trailing after.

Allow me a tangent, dear reader, because I’m reminded of the 2023 re-release of 1979’s notorious Caligula where a producer tried to re-edit the famously trashy movie, hewing closer to author Gore Vidal’s original screenplay and less the explicit excess of producer and Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione’s editorial influence. It seems like so much effort to reclaim one of cinema’s most over-the-top movies, but can you really make a classy version of a movie about the cruel Roman emperor that has a wall of spinning blades as an execution device and copious floating brothels? The movie is forever known for its trashy and outrageous elements because it is emulating an outrageous tyrant of history given to hedonistic and lascivious excess. Nobody wants the “classy” version of this sensational story because that’s the tamped-down and boring version of this story (granted, there are plenty of prurient Guccione additions that we could also do without). Taking sensational melodrama and trying to subvert the sensationalism under the guise of genre deconstruction can work; however, the key is that the “classy” approach has to be a more compelling alternative to the soapier, melodramatic version. I think I would have enjoyed the more sundry and soapy version of May December because with this version I felt too removed, and the movie itself felt too removed and uninterested in so many of its more potent elements for the sake of drifting ambiguity. It’s a drama that seems to stew in downy contemplation but without enough compelling examination to make the effort fulfilling. I kept waiting for the movie to open up, and then the movie just ran out of time. It’s got some admirable goals, and a strong performance from Melton that makes your heart ache, but May December would have been better served either being far more trashy or far more serious rather than straddling a middle ground that left me distant and impatient and ultimately disappointed.

Nate’s Grade: C+

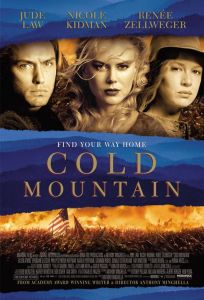

Cold Mountain (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released December 25, 2003:

Premise: At the end of the Civil War, Inman (Jude Law, scruffy) deserts the Confederate lines to journey back home to Ada (Nicole Kidman), the love of his life he’s spent a combined 10 minutes with.

Results: Terribly uneven, Cold Mountain‘s drama is shackled by a love story that doesn’t register the faintest of heartbeats. Kidman is wildly miscast, as she was in The Human Stain, and her beauty betrays her character. She also can’t really do a Southern accent to save her life (I’m starting to believe the only accent she can do is faux British). Law’s ever-changing beard is even more interesting than her prissy character. Renee Zellweger, as a no-nonsense Ma Clampett get-your-hands-dirty type, is a breath of fresh air in an overly stuffy film; however, her acting is quite transparent in an, “Aw sucks, give me one ‘dem Oscars, ya’ll” way.

Nate’’s Grade: C

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I kept meaning to come back to Cold Mountain, a prototypical awards bait kind of movie that never really materialized, but one woman ensured that it would be on my re-watch list for 2003. My wife’s good friend, Abby, was eager to hear my initial thoughts on the movie when I wrote my original review at the age of twenty-one. This is because Cold Mountain is a movie that has stayed with her for the very fact that her grandfather took her to see it when she was only nine years old. While watching, it dawned on nine-year-old Abby that this was not a movie for nine-year-olds, and it’s stuck with her ever since. I think many of us can relate to watching a movie with our parents or family members that unexpectedly made us uncomfortable. For me, it was Species, where I was 13 years old and the movie was about a lady alien trying to procreate. I think my father was happy that I had reached an acceptable age to go see more R-rated movies in theaters. Social media has been awash lately with videos of festive families reacting to the shock value of Saltburn with grumbles and comical discomfort (my advice: don’t watch that movie with your parents). So, Abby, this review is for you, but it’s also, in spirit, for all the Abbys out there accidentally exposed to the adult world uncomfortably in the company of one’s parents or extended family.

Cold Mountain succumbs to the adaptation process of trying to squeeze author Charles Frazier’s 1997 book of the same name into a functional movie structure, but the results, even at 150 minutes, are unwieldy and episodic, arguing for the sake of a wider canvas to do better justice to all the themes and people and minor stories that Frazier had in mind. Director Anthony Minghella’s adaptation hops from protagonist to protagonist, from Inman to Ada, like perspectives for chapters, but there are entirely too many chapters to make this movie feel more like a highly diluted miniseries scrambling to fit all its intended story beats and people into an awards-acceptable running time. This is a star-studded movie, the appeal likely being working with an Oscar-winning filmmaker (1996’s The English Patient) of sweep and scope and with such highly regarded source material, a National Book Award winner. The entire description of Cold Mountain, on paper, sounds like a surefire Oscar smash for Harvey Weisntein to crow over. Yet it was nominated for seven Academy Awards but not Best Picture, and it only eventually won a single Oscar, deservedly for Renee Zellweger. I think the rather muted response to this Oscar bait movie, and its blip in a lasting cultural legacy, is chiefly at how almost comically episodic the entire enterprise feels. This isn’t a bad movie by any means, and quite often a stirring one, but it’s also proof that Cold Mountain could have made a really great miniseries.

The leading story follows a disillusioned Confederate defector, Inman (Jude Law), desperately trying to get back home to reunite with his sworn sweetheart, Ada (Nicole Kidman), who is struggling mightily to maintain her family’s farm after the death of her father. That’s our framework, establishing Inman as a Civil War version of Odysseus fighting against the fates to return home. Along the way he surely encounters a lot of famous faces and they include, deep breath here, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Natalie Portman, Giovanni Ribisi, Cillian Murphy, Eileen Atkins, Taryn Manning, Melora Walters, Lucas Black, and Jena Malone. Then on Ada’s side of things we have Zellweger, Donald Sutherland, a villainous Ray Winstone, Brendan Gleeson, Charlie Hunam, Kathy Baker, Ethan Suplee, musician Jack White, and Emily Descehanel, and this is the storyline that stays put in the community of Cold Mountain, North Carolina.

That is a mountain of stars, and with only 150 minutes, the uneven results can feel like one of those big shambling movies from the 1950s that have dozens of famous actors step on and as quickly step off the ride. Poor Jena Malone (Rebel Moon) appears as a ferry lady and literally within seconds of offering to prostitute herself she is shot dead and falls into the river (well, thanks for stopping by Jena Malone, please enjoy your parting gift of this handsome check from Miramax). Reducing these actors and the characters they are playing down to their essence means we get, at most, maybe 10-15 minutes with them and storylines that could have been explored in richer detail. Take Portman’s character, a widowed mother with a baby trying to eke out a living, one of many such fates when life had to continue after the men ran to war for misbegotten glory. She looks at Inman with desperate hunger, but it’s not exactly lust, it’s more human connection. When she requests that Inman share her bed, it’s just to feel another warm presence beside her, someone that can hold her while she weeps about the doomed fate of her husband and likely herself. There’s a strong character here but she’s only one stop on our expedited tour. The same with Hoffman’s hedonistic priest, a man introduced by throwing the body of a slave woman he impregnated over a ridge, which might be the darkest incidental moment of the whole movie. His character is played as comic relief, a loquacious man of God who cannot resist the pleasures of the flesh, but even he comes and goes like the rest of our litany of very special guest stars. They feel more like ideas than characters.

This is a shame because there are some fantastic scenes and moments that elevate Cold Mountain. The opening Civil War battle is an interesting and largely forgotten (sorry Civil War buffs) battle that begins with a massive surprise attack that produces a colossal explosion and crater and turns into a hellish nightmare. Granted, the movie wants us to sympathize with the Confederates who were bamboozled by the Yankee explosives buried under their lines, and no thank you. The demise of Hoffman’s character comes when he and Inman are captured and join a chain gang, and they try running up a hill to get free from approaching Union troops. The Confederates shoot at the fleeing men, eventually only with Inman left, who struggles to move forward with the weight of all these dead men attached to him. When they start rolling down the hill, it becomes a deeply macabre and symbolic struggle. The stretch with Portman (May December) is tender until it goes into histrionics, with her literal baby being threatened out in the cold by a trio of desperate and starving Union soldiers (one of which played by Cillian Murphy). It’s a harrowing scene that reminds us about the sad degradation of war that entangles many innocents and always spills over from its desired targets. However, this theme that the war and what it wrought is sheer misery is one Minghella goes to again and again, but without better characterization with more time for nuance, it feels like each character and moment is meant to serve as another supporting detail in an already well-proven thesis of “war is hell.”

Even though I had previously watched the movie back in 2003, I was hoping that after two hours of striving to reunite, that Inman and Ada would finally get together and realize, “Oh, we don’t actually like each other that much,” that their romance was more a quick infatuation before the war, that both had overly romanticized this beginning and projected much more onto it from the years apart, and now that they were back together with the actual person, not their idealized imaginative version, they realized what little they had in common or knew about each other. It would have been a well-played subversion, but it also would have been a welcomed shakeup to the Oscar-bait romantic drama of history. Surely this had to be an inconvenient reality for many, especially considering that the men returning from war, the few that did, were often not the same foolhardy young men who leapt for battle.

Zellweger (Judy) was nominated for Best Actress in the preceding two years, for 2001’s Bridget Jones Diary and 2002’s Chicago, which likely greased the runway for her Supporting Actress win from Cold Mountain. There is little subtlety about her “aw shucks” homespun performance but by the time she shows up, almost fifty minutes into the movie, she is such a brash and sassy relief that I doubt anyone would care. She’s the savior of the Cold Mountain farm, and she’s also the savior of the flagging Ada storyline. Pity Ada who was raised to be a nice dutiful wife and eventual mother but never taught practical life skills and agricultural methods. Still, watching this woman fail at farming will only hold your attention for so long. Zellweger is a hoot and the spitfire of the movie, and she even has a nicely rewarding reconciliation with her besotted old man, played by Brendan Gleeson, doing his own fiddlin’ as an accomplished violin player. As good as Zellweger is in this movie is exactly how equally bad Kidman’s performance is. Her Southern accent is woeful and she cannot help but feel adrift, but maybe that’s just her channeling Ada’s beleaguered plight.

I think there’s an extra layer of entertainment if you view Inman’s journey in league with Odysseus; there’s the dinner that ends up being a trap, the line of suitors trying to steal Ada’s home and hand in the form of the duplicitous Home League boys, Hoffman’s character feels like a lotus eater of the first order, and I suppose one reading could have Portman’s character as the lovesick Calypso. Also, apparently Cold Mountain was turned into an opera in 2015 from the Sante Fe Opera company. You can listen here but I’m not going to pretend I know the difference between good and bad opera. It’s all just forceful shouting to my clumsy ears.

Miramax spent $80 million on Cold Mountain, its most expensive movie until the very next year with 2004’s The Aviator. Miramax was sold in 2010 and had years earlier ceased to be the little studio that roared so mighty during many awards seasons. I think Cold Mountain wasn’t the nail in the coffin for the company but a sign of things to come, the chase for more Oscars and increasingly surging budgets lead the independent film distributor astray from its original mission of being an alternative to the major studio system. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, it had simply become another studio operating from the same playbook. Minghella spent three years bringing Cold Mountain to the big screen, including a full year editing, and only directed one other movie afterwards, 2006’s Breaking and Entering, a middling drama that was his third straight collaboration with Law. Minghella died in 2008 at the still too young age of 54. He never lived to fully appreciate the real legacy of Cold Mountain: making Abby and her grandfather uncomfortable in a theater. If it’s any consolation to you, Abby, I almost engineered my own moment trying to re-watch this movie and having to pause more than once during the sex scene because my two children wanted to keep intruding into the room. At least I had the luxury of a pause button.

Re-View Grade: B-

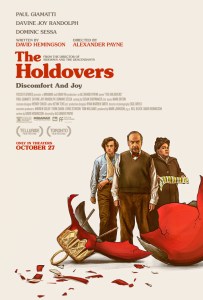

The Holdovers (2023)

Oscar-winning director Alexander Payne and Paul Giamatti re-team for a poignant and crowd-pleasing holiday movie about outcasts sharing their vulnerabilities with one another over the last week of 1970. Giamatti stars as Paul Hunham, a rigid history teacher at an all-boys academy who just happens to be liked by nobody including his colleagues. He gets the unfortunate duty of staying on campus during the Christmas break and watching over any students who cannot return home for the holidays. Angus (Dominic Sessa) is the last student remaining, a 15-year-old with a history of lying, defiance, and on the verge of expulsion. The other holdover member is Mary (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) as the kitchen staff forced to feed them, a woman whose own adult son recently died in Vietnam. The teacher and student butt heads as they try and co-exist without other supervision, eventually connecting once they lower their defenses and attempt to see one another as flawed human beings with real hurts and disappointments. It’s a simple movie about three different characters from very different experiences pushing against one another and finding common ground. It’s a relationship movie that has plenty of wry humor and strong character beats from debut screenwriter David Hemingson. There may not be a larger theme or thesis that emerges, but being a buddy dramedy about hurt people building their friendships is still a winning formula with excellent writing, directing, and acting working in tandem, which is what we have with The Holdovers. It’s a slice of-life movie that makes you want bigger slices, especially for Mary’s character who thought having her son attend the same prep school would set him up for a promising future (he was denied college admission and thus deferral from the draft). It’s a beguiling movie because it’s about sad and lonely people over the holidays, each experiencing their own level of grief, and the overall feel is warm and fuzzy, like a feel-good movie about people feeling bad. That’s the Alexander Payne effect, finding an ironic edge to nostalgia while exploring hard-won truths with down-on-their-luck characters. The Holdovers is an enjoyable holiday comedy with shades of bitterness to go along with the feel-good uplift. It’s Payne’s Christmas movie and that is is own gift to moviegoers.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003) [Review Re-View]

Originally released November 14, 2003:

Without sounding easily amused, this movie really is glorious filmmaking. With Peter Weir’’s steady and skilled direction we get to really know the life of the early 19th century. We also get to know an armada of characters and genuinely feel for them. Russell Crowe is outstanding as Captain Jack Aubrey. His physicality and emotions are expertly showcased. When he gives a motivational speech you’’d understand why people would follow him to the ends of the Earth. Paul Bettany (again buddying up to Crowe after ‘A Beautiful Mind’) is Oscar-worthy for his performance as the ship’s’ doctor and confidant to the Captain. He’’s not afraid to question the Captain’’s motives, like following a dangerous French ship all around South America. ‘Master and Commander ’hums with life, and the battle sequences are heart-stopping and beautifully filmed. It took three studios to produce and release this and every dollar spent can be seen on the screen. ‘Master and Commander’ is fantastic, compelling entertainment with thrills, humanity, and wonder. It’’s grand old school Hollywood filmmaking.

Nate’s Grade: A

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER