Blog Archives

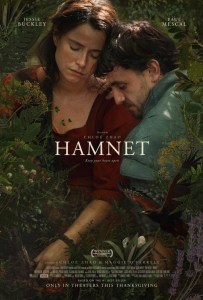

Hamnet (2025)

It’s the sad Shakespeare movie, and with Paul Mescal (Gladiator II) as Will, it could just as easily be dubbed the Sad Sexy Shakespeare movie. Hamnet is a fictionalized account of Will and his wife Agnes (Jessie Buckley) processing the death of their young son, Hamnet, which we’re told in opening text is a common name transference for Hamlet. Right away, even before co-writer/director Chloe Zhao (Nomadland, Eternals) brings her usual stately somberness, you know what kind of movie you’re in for. It’s pretty (and famous) people in pain. The entire time I was watching this kid Hamnet and just waiting for the worst. It doesn’t arrive until 75 minutes into the movie, and it’s thoroughly devastating, especially the circumstances surrounding the loss. This is less a Shakespeare movie and more a Mrs. Shakespeare movie, which is more illuminating since she’s typically overshadowed by her verbose husband. She’s an intriguing figure who shares some witchy aspects, communing with nature and even foretelling her future husband’s greatness and dying with only two living children, which presents a pall when she has three eventual children. Once Will finds success as a London playwright, he feels like an absentee father and husband, briefly coming in and out of his family’s life in Stratford. However, the final act is what really doesn’t seal the movie for me. I don’t think it’s really a spoiler to admit the final 15 minutes of the movie is basically watching Hamlet performed on stage, with Agnes as the worst audience member, frequently talking through the show and loudly harassing the actors before finally succumbing to the artistry of the play and finding it a fitting outlet for her grief. In short, the movie is meant to provide more personal insight and tragedy into this famous play, asking the viewer to intuit more meaning (“Oh, Hamlet is his dead son, Hamnet! I get it”), but ultimately the ending is just watching Hamlet. I don’t feel like we get any meaningful insight into William Shakespeare as a person besides his irritation at being a Latin teacher, and frustratingly, Agnes is constrained as well, held in a narrow definition of the grieving mother. This is a shame since she showed such fire and individuality in the first half. Buckley (The Lost Daughter) is terrific, ethereal, earthy, and heartbreaking and a shoo-in for an Oscar. I found her final moments, especially reaching out to her son, so to speak, especially poignant. Hamnet is a good-looking, well-acted movie about sad famous people who then rely upon the arts to help heal their gulf of sadness. There’s not much more to Hamnet than that, but with such exceptional professionals and artists at the ready, it might be more than enough for most.

It’s the sad Shakespeare movie, and with Paul Mescal (Gladiator II) as Will, it could just as easily be dubbed the Sad Sexy Shakespeare movie. Hamnet is a fictionalized account of Will and his wife Agnes (Jessie Buckley) processing the death of their young son, Hamnet, which we’re told in opening text is a common name transference for Hamlet. Right away, even before co-writer/director Chloe Zhao (Nomadland, Eternals) brings her usual stately somberness, you know what kind of movie you’re in for. It’s pretty (and famous) people in pain. The entire time I was watching this kid Hamnet and just waiting for the worst. It doesn’t arrive until 75 minutes into the movie, and it’s thoroughly devastating, especially the circumstances surrounding the loss. This is less a Shakespeare movie and more a Mrs. Shakespeare movie, which is more illuminating since she’s typically overshadowed by her verbose husband. She’s an intriguing figure who shares some witchy aspects, communing with nature and even foretelling her future husband’s greatness and dying with only two living children, which presents a pall when she has three eventual children. Once Will finds success as a London playwright, he feels like an absentee father and husband, briefly coming in and out of his family’s life in Stratford. However, the final act is what really doesn’t seal the movie for me. I don’t think it’s really a spoiler to admit the final 15 minutes of the movie is basically watching Hamlet performed on stage, with Agnes as the worst audience member, frequently talking through the show and loudly harassing the actors before finally succumbing to the artistry of the play and finding it a fitting outlet for her grief. In short, the movie is meant to provide more personal insight and tragedy into this famous play, asking the viewer to intuit more meaning (“Oh, Hamlet is his dead son, Hamnet! I get it”), but ultimately the ending is just watching Hamlet. I don’t feel like we get any meaningful insight into William Shakespeare as a person besides his irritation at being a Latin teacher, and frustratingly, Agnes is constrained as well, held in a narrow definition of the grieving mother. This is a shame since she showed such fire and individuality in the first half. Buckley (The Lost Daughter) is terrific, ethereal, earthy, and heartbreaking and a shoo-in for an Oscar. I found her final moments, especially reaching out to her son, so to speak, especially poignant. Hamnet is a good-looking, well-acted movie about sad famous people who then rely upon the arts to help heal their gulf of sadness. There’s not much more to Hamnet than that, but with such exceptional professionals and artists at the ready, it might be more than enough for most.

Nate’s Grade: B-

Women Talking (2022)

The hard-hitting Oscar-worthy drama Women Talking could have been titled Twelve Angry Women, but with the necessary subtitle: But They’re Very Justified in Their Rage. It is, as the title suggests, a movie almost entirely about women talking in one central location, enough so to feel like a stage play captured for the screen. However, the reason these women are assembled is heartbreaking, infuriating, and eminently engrossing. Women Talking demands to be heard.

The hard-hitting Oscar-worthy drama Women Talking could have been titled Twelve Angry Women, but with the necessary subtitle: But They’re Very Justified in Their Rage. It is, as the title suggests, a movie almost entirely about women talking in one central location, enough so to feel like a stage play captured for the screen. However, the reason these women are assembled is heartbreaking, infuriating, and eminently engrossing. Women Talking demands to be heard.

The dozen women have gathered to debate the future of their participation in their community, a closed-off Mennonite coalition. They are victims of heinous sex crimes and general repression, debating between staying and fighting and abandoning their way of life. These women are talking about their own agency and what their collective response will be to the great wrongs that have prevailed upon them. It’s not just that the women of this community have been preyed upon by predators in their midst, their trauma has been dismissed as ghosts and devils until literal men were literally caught and apprehended. The next part is even more galling, as the guilty men will be returning back to the community and the women are expected to forgive the predators and go back to life as it has been. Except how exactly has life been for the women of this small community? The assaults have been going on for decades, enough that many of the children are the byproducts of their abusers. One grandmother is brought to tears that she should have done more to protect her adult daughter, herself married to an abusive man. The systematic nature of this abuse is the core of their deliberation. Can they stay and reform a broken society from inside, or is the best hope radically breaking away and starting anew without the men?

The movie also serves as a debate over the capacity for grace and forgiveness, reminding me in subject as well as the approach of last year’s equally hard-hitting and equally spellbinding indie, Mass. I found it especially insulting that these women are expected, by the male leaders, to simply forgive and forget, to shuffle back to subservience. It’s a larger philosophical discussion over the nature of grace and accountability. It would be showing grace to these men to forgive them when they do not deserve it, and surely the male leaders would underline this point in a comparison with their religious text, akin to Jesus forgiving those who crucified him. However, if forgiveness is not the catalyst for reform and reclamation, then it’s just another empty gesture that maintains the status quo of abuse going unpunished and the abusers being protected. It’s easy to make larger connections to larger societies protecting predators through conditioned silence. The entertainment industry has been rife with bad men, and yes it’s typically men, behaving criminally and being protected by their position, and it might be easy to make connections with Women Talking and She Said, the fact-based take-down of Harvey Weinstein. Are these people worthy of forgiveness or is the patriarchal system of power (women aren’t even allowed to learn to read and write in this community) beyond salvaging? Within minutes of watching, I was already shaking my head and saying they should burn it all to the ground.

The movie also serves as a debate over the capacity for grace and forgiveness, reminding me in subject as well as the approach of last year’s equally hard-hitting and equally spellbinding indie, Mass. I found it especially insulting that these women are expected, by the male leaders, to simply forgive and forget, to shuffle back to subservience. It’s a larger philosophical discussion over the nature of grace and accountability. It would be showing grace to these men to forgive them when they do not deserve it, and surely the male leaders would underline this point in a comparison with their religious text, akin to Jesus forgiving those who crucified him. However, if forgiveness is not the catalyst for reform and reclamation, then it’s just another empty gesture that maintains the status quo of abuse going unpunished and the abusers being protected. It’s easy to make larger connections to larger societies protecting predators through conditioned silence. The entertainment industry has been rife with bad men, and yes it’s typically men, behaving criminally and being protected by their position, and it might be easy to make connections with Women Talking and She Said, the fact-based take-down of Harvey Weinstein. Are these people worthy of forgiveness or is the patriarchal system of power (women aren’t even allowed to learn to read and write in this community) beyond salvaging? Within minutes of watching, I was already shaking my head and saying they should burn it all to the ground.

Women Talking is powerful and somber without being overly grave to the detriment of the material. It’s never taken anything less than serious, but the subject matter is handled very sensitively and even rated PG-13. Under the careful guidance of writer/director Sarah Polley (Away From Her, Stories We Tell), the film doesn’t soft-pedal the abuse these women have suffered but it doesn’t wallow in it either, getting overloaded with sordid details. The screenplay unfolds key pieces of information over time, allowing the audience to piece together a fuller picture (I didn’t even realize the family connection of the dozen women until an hour in). It would be easy if the only response explored was one of unfathomable rage, best exemplified by a stirring monologue where Claire Foy (The Crown, First Man) rattles off what she will do to protect her young daughter including murder, including vying with the Almighty, and even including spending eternity in hell. It’s easy to be all teeth-gnashing vengeance and fury, and entirely deserved considering these women are already looked upon as second-class citizens. However, Polley aligns her movie as a debate between anguish and hope and the difference between false and real hope. Is it real to hope that these men will change? Is it real to hope that August (Ben Whishaw), a college-educated child of a former outcast, can break the cycle? By the end, the main feeling I had was catharsis, that these women can chart a new, better path.

Given the heavy subject matter and the ensemble nature of the production, you would be right to assume that this is an actors’ showcase. The three biggest roles belong to Foy’s Salome, Rooney Mara’s Ona, and Jessie Buckley’s Mariche, each presenting a different perspective. Salome wants to stay but mostly as a means of collecting vengeance for her and her daughter. Mariche wants to forgive the men because, if they do exile themselves, they are told their immortal souls will be denied the kingdom of heaven. It also happens that Mariche’s alcoholic husband is one of the accused men returning. Ona is pregnant with her attacker’s child and questioning which setting would be best for her, staying with what she knows or risking a new life, for better or worse. Foy and Buckely (The Lost Daughter, Men) each have a signature monologue opening up their character perspective and each of them cinches it (call it their “Oscar clip moments”). Mara (Nightmare Alley) has the more contemplative and subdued role, which makes it less showy. Her character is the one who questions the most the value of forgiveness, and of course whether it counts when forgiveness is forced with the threat of eternal damnation. If Salome is the movie’s fury, then Ona is a reflection of begrudging hope, and Mara succeeds with a noble sense of grace.

Given the heavy subject matter and the ensemble nature of the production, you would be right to assume that this is an actors’ showcase. The three biggest roles belong to Foy’s Salome, Rooney Mara’s Ona, and Jessie Buckley’s Mariche, each presenting a different perspective. Salome wants to stay but mostly as a means of collecting vengeance for her and her daughter. Mariche wants to forgive the men because, if they do exile themselves, they are told their immortal souls will be denied the kingdom of heaven. It also happens that Mariche’s alcoholic husband is one of the accused men returning. Ona is pregnant with her attacker’s child and questioning which setting would be best for her, staying with what she knows or risking a new life, for better or worse. Foy and Buckely (The Lost Daughter, Men) each have a signature monologue opening up their character perspective and each of them cinches it (call it their “Oscar clip moments”). Mara (Nightmare Alley) has the more contemplative and subdued role, which makes it less showy. Her character is the one who questions the most the value of forgiveness, and of course whether it counts when forgiveness is forced with the threat of eternal damnation. If Salome is the movie’s fury, then Ona is a reflection of begrudging hope, and Mara succeeds with a noble sense of grace.

There are two minor quibbles I have with Women Talking that hold it slightly back for me, and it’s not the locked-in setting making the proceedings feel like a staged play. Polley uses visual inserts and cutaways to devastating effect to highlight the women’s trauma, from awakening to the aftermath of assault to miscarriages, notions to heighten the visual storytelling potential of the medium without digging into exploitation and losing the tasteful tone. The directing even takes a few cues from Sydeny Lumet’s work from 12 Angry Men. One critical aspect that holds back the movie, again only slightly, is that the characters tend to feel a little more like various points of view rather than finely developed characters. Given the nature of the debate, there’s a lot of ground to cover, and it’s a smart storytelling move to coalesce. It just slightly limits some emotional engagement; it’s still there because of the skill of the actors and every drop of empathy they rightly earn, but the characters aren’t as well realized as they could have been. This can also be simply because we’re dealing with a dozen characters to try and supply enough material for. Even in 12 Angry Men, not every juror is going to be given equal importance (nobody cares about you, juror #7, so sit down). I reflect back to Mass, an excellent 2021 movie that you should seek out, and how personable and in-depth those characters came across over their feature-length sit-down. It also helps that it only had four characters to balance. The other minor criticism I have is the overemphasis the movie places on a long-in-the-works romance between Ona and August, who maybe has more screen time than maybe any woman. For a movie dealing with the sexual and emotional trauma of women and them taking account, I’m left uncertain about the amount of time we spend on an unrequited romance. It’s not like Polley is elbowing in wacky rom-com material, as it all likewise carries the same subdued tone. I just don’t know if this movie needs a romance elevated during its otherwise 100 plaintive minutes.

Women Talking is an urgent movie that every person should watch. The central dynamic is radiating with dramatic potential, and the actors are uniformly excellent, even the youngest actors handling some very touchy material. Polley’s direction is stately and subdued without removing any of the surging emotional power inherent in her drama. I’m overjoyed that Polley has returned back to filmmaking as she hasn’t made a movie in ten years. It’s a triumphant return for Polley, one that will likely have her vying on the biggest stages come awards season. Women Talking is timely and, unfortunately, also timeless. By the end, you’ll feel slightly exhausted but better for it, like the euphoria that comes after a good cry and you feel like, having pushed through, you’ll be better for it.

Women Talking is an urgent movie that every person should watch. The central dynamic is radiating with dramatic potential, and the actors are uniformly excellent, even the youngest actors handling some very touchy material. Polley’s direction is stately and subdued without removing any of the surging emotional power inherent in her drama. I’m overjoyed that Polley has returned back to filmmaking as she hasn’t made a movie in ten years. It’s a triumphant return for Polley, one that will likely have her vying on the biggest stages come awards season. Women Talking is timely and, unfortunately, also timeless. By the end, you’ll feel slightly exhausted but better for it, like the euphoria that comes after a good cry and you feel like, having pushed through, you’ll be better for it.

Nate’s Grade: B+

Men (2022)

Longtime Hollywood go-to genre screenwriter Alex Garland has only directed two other movies, 2015’s Ex Machina and 2018’s Annihilation, both using the realm of science fiction to explore feminine trauma and the sea change of societies on a precipice. I loved Ex Machina and admired but didn’t fully enjoy Annihilation. His newest movie, a small-scale indie horror titled Men, lands somewhere in the middle. It’s in keeping with his other movies, following a woman named Harper (Jessie Buckley) dealing with trauma, and it’s atmospheric while still maintaining a clear point of view that could likely rub people the wrong way. It’s an uncomfortable nightmare of a horror movie and one that isn’t as deep as it appears to be.

Longtime Hollywood go-to genre screenwriter Alex Garland has only directed two other movies, 2015’s Ex Machina and 2018’s Annihilation, both using the realm of science fiction to explore feminine trauma and the sea change of societies on a precipice. I loved Ex Machina and admired but didn’t fully enjoy Annihilation. His newest movie, a small-scale indie horror titled Men, lands somewhere in the middle. It’s in keeping with his other movies, following a woman named Harper (Jessie Buckley) dealing with trauma, and it’s atmospheric while still maintaining a clear point of view that could likely rub people the wrong way. It’s an uncomfortable nightmare of a horror movie and one that isn’t as deep as it appears to be.

Men accomplishes what I had been hoping with 2021’s Chaos Walking, namely portraying everyday life as a woman as a living horror movie. It’s a highly metaphorical and atmospheric movie but, at its core, it’s all about the danger, discomfort, and indignities that women endure on a near daily basis dealing with men. I don’t think the movie has as much to say on the topic or is as ambiguous as others are presenting (more on this later), but its central theme is so bracingly direct and deeply unsubtle but sometimes a sledgehammer is better than a scalpel. This is an intense movie from the start and a frequent reminder of the hazards of being female in a patriarchy. Each of the men that Harper encounters represents a different facet of toxic masculinity. The seemingly kindly priest, who places his hand on Harper’s thigh to “calm her,” is projecting guilt and blame onto her for the actions of men and views her femininity as a corrupting and tempting influence, very akin to Eve. The little boy, who likes wearing creepy masks, is a brat who refuses to accept no for an answer and turns on a dime into verbal attacks, much like the men of the Internet ready to flip at a moment’s notice. The police officer is dismissive of Harper’s account of being harassed and threatened, representing a legal arm that often downplays and diminishes women as victims. There’s even Geoffrey, who seems almost like the best man in town by default, is aloof, doesn’t understand boundaries, and is trying to present himself as a “nice guy” looking for his delayed dues. The only person in town that seems sympathetic to Harper is the one female police officer who takes her statement. Each man is played by Rory Kinnear (Our Flag Means Death) for thematic reasons. I’ve read people complain, “Why wouldn’t Harper realize this obvious similarity in the town’s men?” The answer is simple: it’s because the men do not literally all look the same. It’s meant to reflect Harper’s perspective, much like 2015’s Anomalisa where the protagonist viewed every person as looking and sounding like Tom Noonan until one unique voice cuts through the malaise and monotony. This movie is wall-to-wall with uncomfortable, seething misogyny in many forms, and given the times we live in, I wouldn’t blame any woman saying, “No thanks.” I’m glad I watched this one alone and without my now-fiance, as she would have brought this up forever as a “You made me watch…” tease.

The flashbacks with Harper’s unstable ex-husband James (Paapa Essiedu) are the most personally illuminating and make up a significant portion of the narrative, as Harper is forced into her painful memories from her present encounters. Her husband showcases clear signs of being mentally ill and is also verbally and physically abusive to her. He greets her news about seeking a divorce by declaring that if she doesn’t take him back, he will kill himself. This emotional blackmail feels par for the course in this relationship and another sign why Harper would want out for her own well-being. The movie opens with Harper watching James fall to his death, and this trauma is what she’s processing through every male interaction. James is indicative of a kind of man that imposes demands on their partner without holding themselves to the same standards, but it goes beyond hypocrisy; it’s about a damaged person who holds another hostage with further threats of their damage. It’s a person who puts the entire onus of their existence onto another, removing their own personal responsibility, and thus blaming the convenient external party when something inevitably goes wrong. This central relationship is revisited in different ways throughout the movie, and you could even argue that Men is a metaphorical journey of Harper trying to shed herself from the weight of this disturbed dead man.

The flashbacks with Harper’s unstable ex-husband James (Paapa Essiedu) are the most personally illuminating and make up a significant portion of the narrative, as Harper is forced into her painful memories from her present encounters. Her husband showcases clear signs of being mentally ill and is also verbally and physically abusive to her. He greets her news about seeking a divorce by declaring that if she doesn’t take him back, he will kill himself. This emotional blackmail feels par for the course in this relationship and another sign why Harper would want out for her own well-being. The movie opens with Harper watching James fall to his death, and this trauma is what she’s processing through every male interaction. James is indicative of a kind of man that imposes demands on their partner without holding themselves to the same standards, but it goes beyond hypocrisy; it’s about a damaged person who holds another hostage with further threats of their damage. It’s a person who puts the entire onus of their existence onto another, removing their own personal responsibility, and thus blaming the convenient external party when something inevitably goes wrong. This central relationship is revisited in different ways throughout the movie, and you could even argue that Men is a metaphorical journey of Harper trying to shed herself from the weight of this disturbed dead man.

However, the real draw of Men is its allegorical nature and that is bound to rub plenty of viewers differently. The best comparison I can make is 2017’s mother!, a deeply polarizing movie from Darren Aronofsky (Black Swan, Requiem for a Dream) that completely existed as a none-too-subtle Biblical allegory as the primary plot. Usually, screenwriters will work with metaphor and allegory as subtext, adding extra depth and meaning to their storytelling. We don’t expect it to serve as the primary narrative. With Men, like mother!, it is indeed the primary narrative. I can reduce the plot down to this description: woman explores English countryside and is harassed by men of various forms. To be fair, Jaws could be reduced to “guys try to kill big shark,” so this is a little reductive. The emphasis is on exploring the experiences that Harper is enduring, her exploration of nature and seclusion that, at each turn, gets sabotaged by a man. If you’re not open to a narrative that is a little looser and more atmospheric, you’ll find the movie to be plodding and overwrought. When Act Three kicks in, the movie goes full-on into bonkers horror and isn’t even flirting with a direct correlation with reality any longer. I can safely say that some of the bizarre imagery is truly some of the strangest and grossest things I’ve ever seen in any movie. The chief symbol (toxic men begetting toxic men) is central to the icky body horror cavalcade.

However, the movie’s allegory doesn’t lend itself to much in the way of interpretation. That’s not exactly a creative hindrance; stories can simply be what they are intended to be. Men is fairly obvious what it’s about even from the starting point of its one-word title. It’s a movie heavy in allegory but the allegory itself is also pretty unambiguous and straightforward. There may be interpretation for this symbol or that but Garland’s horror movie is pretty much thematically obvious. It all supports his theme about the horror of being a woman in modern society, magnified across a metaphorical horror movie canvas. I’m sure there will be others who go into great detail to dissect this movie but all of it seems to come to the same basic conclusion, and that’s fine.

However, the movie’s allegory doesn’t lend itself to much in the way of interpretation. That’s not exactly a creative hindrance; stories can simply be what they are intended to be. Men is fairly obvious what it’s about even from the starting point of its one-word title. It’s a movie heavy in allegory but the allegory itself is also pretty unambiguous and straightforward. There may be interpretation for this symbol or that but Garland’s horror movie is pretty much thematically obvious. It all supports his theme about the horror of being a woman in modern society, magnified across a metaphorical horror movie canvas. I’m sure there will be others who go into great detail to dissect this movie but all of it seems to come to the same basic conclusion, and that’s fine.

Men is the kind of movie that almost wears out its welcome at 100 minutes. The technical merits are strong, the photography and imagery are lush and transporting, and Buckley (The Lost Daughter) is a great actress to hinge a story of mounting distress and terror. If you’re the kind of person that seeks out new cinematic avenues of nightmare fuel, then the final act and its chief monster with its distinct disfigurement will sate your morbid appetite. It’s an effective and evocative movie but it’s also the same thesis statement hammered again and again. While the movie has some perplexing moments, there isn’t much to unpack as far as meaning, and ultimately that can limit some of the play of a movie built on the engine of metaphor. It feels like a scream against the overwhelming and entrenched social forces of misogyny, and I cannot say whether it’s worth 100 minutes of squirm-inducing discomfort of art imitating all-too-real life.

Nate’s Grade: B-

I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020)

I expect strange from a Charlie Kaufman movie; that goes without saying. I also expect some high concept turned inward and, most importantly, a humane if bewildered anchor. His other movies have dealt with similar themes of depression (Anomalisa), relationship entropy (Eternal Sunshine), identity (Being John Malkovich), and regret from afar (Synecdoche, New York). However, no matter the head-spinning elements, the best Kaufman movies have always been the ones that embrace a human, if flawed, experience with sincerity rather than ironic detachment. There’s a reason that Eternal Sunshine is a masterpiece and that nobody seems to recall 2002’s Human Nature (ironic title for this reference). 2015’s Anomalisa was all about one man trying to break free from the fog of his mind, finding a woman as savior, and then slowly succumbing to the same trap. Even with its wilder aspects, it was all about human connection and disconnection. By contrast, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is all about a puzzle, and once you latch onto its predictable conclusion, it doesn’t provide much else in the way of understanding. It’s more a “so, that’s it?” kind of film, an exercise in trippy moments intended to add up to a whole, except it didn’t add up for me. I held out hope, waiting until the very end to be surprised at some hidden genius that had escaped me, for everything to come together into a more powerful whole, like Synecdoche, New York. It didn’t materialize for me and I was left wondering why I spent two hours with these dull people.

I expect strange from a Charlie Kaufman movie; that goes without saying. I also expect some high concept turned inward and, most importantly, a humane if bewildered anchor. His other movies have dealt with similar themes of depression (Anomalisa), relationship entropy (Eternal Sunshine), identity (Being John Malkovich), and regret from afar (Synecdoche, New York). However, no matter the head-spinning elements, the best Kaufman movies have always been the ones that embrace a human, if flawed, experience with sincerity rather than ironic detachment. There’s a reason that Eternal Sunshine is a masterpiece and that nobody seems to recall 2002’s Human Nature (ironic title for this reference). 2015’s Anomalisa was all about one man trying to break free from the fog of his mind, finding a woman as savior, and then slowly succumbing to the same trap. Even with its wilder aspects, it was all about human connection and disconnection. By contrast, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is all about a puzzle, and once you latch onto its predictable conclusion, it doesn’t provide much else in the way of understanding. It’s more a “so, that’s it?” kind of film, an exercise in trippy moments intended to add up to a whole, except it didn’t add up for me. I held out hope, waiting until the very end to be surprised at some hidden genius that had escaped me, for everything to come together into a more powerful whole, like Synecdoche, New York. It didn’t materialize for me and I was left wondering why I spent two hours with these dull people.

A Young Woman (Jessie Buckley) is traveling with her boyfriend Jake (Jessie Plemons) to meet his parents for the first time. It’s snowy Oklahoma, barren, dreary, and not encouraging. In the opening line we hear our heroine divulge the title in narration, which we think means their relationship but might prove to have multiple interpretations. It only gets more awkward as she meets Jake’s parents (David Thewlis, Toni Collette) and weird things continue happening. The basement door is chained with what look like claw marks. People rapidly age. The snow keeps coming down and the Young Woman is eager to leave for home but she might not be able to ever get home.

The title is apt because I was thinking of ending things myself after an hour of this movie. Kaufman’s latest is so purposely uncomfortable that it made me cringe throughout, and not in a good squirmy way that Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster) has perfected. Kaufman wants to dwell and drag out the discomfort, starting with the relationship between Young Woman and Jake. She’s already questioning whether or not she should be meeting his parents and their inbound conversations in the car are long and punctuated by Jake steering them into proverbial dead ends. He’s a dolt. You clearly already don’t feel a connection between them, and this is then extended into the family meet and dinner, which takes up the first hour of the movie. I’m Thinking of Ending Things tips its hand early about not trusting our senses and that we are in the realm of an unreliable narrator. Characters will suddenly shift placement in the blink of an eye, like we blacked out, and character names, professions, histories, and even ages will constantly alter. The Young Woman is a theoretical physicist, then a gerontologist, then her “meet cute” with Jake borrows liberally from a rom-com directed by Robert Zeemckis in this universe (my one good laugh). Jake’s parents will go from old to young and young to old without comment. All the surreal flourishes keep your attention, at least for the first half, as we await our characters to be affected by their reality, but this never really happens. Our heroine feels less like our protagonist (yes, I know there’s a reason for this) because her responses to the bizarre are like everyone else. The entire movie feels like a collection of incidents that could have taken any order, many of which could also have been left behind considering the portentous 135-minute running time.

The title is apt because I was thinking of ending things myself after an hour of this movie. Kaufman’s latest is so purposely uncomfortable that it made me cringe throughout, and not in a good squirmy way that Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster) has perfected. Kaufman wants to dwell and drag out the discomfort, starting with the relationship between Young Woman and Jake. She’s already questioning whether or not she should be meeting his parents and their inbound conversations in the car are long and punctuated by Jake steering them into proverbial dead ends. He’s a dolt. You clearly already don’t feel a connection between them, and this is then extended into the family meet and dinner, which takes up the first hour of the movie. I’m Thinking of Ending Things tips its hand early about not trusting our senses and that we are in the realm of an unreliable narrator. Characters will suddenly shift placement in the blink of an eye, like we blacked out, and character names, professions, histories, and even ages will constantly alter. The Young Woman is a theoretical physicist, then a gerontologist, then her “meet cute” with Jake borrows liberally from a rom-com directed by Robert Zeemckis in this universe (my one good laugh). Jake’s parents will go from old to young and young to old without comment. All the surreal flourishes keep your attention, at least for the first half, as we await our characters to be affected by their reality, but this never really happens. Our heroine feels less like our protagonist (yes, I know there’s a reason for this) because her responses to the bizarre are like everyone else. The entire movie feels like a collection of incidents that could have taken any order, many of which could also have been left behind considering the portentous 135-minute running time.

There are a lot of weird moments and overall this movie will live on in my memory only for its moments. We have a lengthy choreographed dance with doubles for Jake and the Young Woman, an animated commercial for ice cream, an acceptance speech directly cribbed from A Beautiful Mind that then leads directly into a performance from Oklahoma!, an entire resuscitation of poetry and a film review by Pauline Kael, talking ghosts, and more. It’s a movie of moments because every item is meant to be a reflection of one purpose, but I didn’t feel like that artistic accumulation gave me better clarity. There’s solving the plot puzzle of what is happening, the mixture of the surreal with the everyday, but its insight is limited and redundant. The film’s conclusion wants to reach for tragedy but it doesn’t put in the work to feel tragic. It’s bleak and lonely but I doubt that the characters will resonate any more than, say, an ordinary episode of The Twilight Zone. Everything is a means to an ends to the mysterious revelation, which also means every moment has the nagging feeling of being arbitrary and replaceable. The second half of this movie, once they leave the parents’ home, is a long slog that tested my endurance.

Buckley (HBO’s Chernobyl) makes for a perfectly matched, disaffected, confused, and plucky protagonist for a Kaufman vehicle. She has a winsome matter of a person trying their best to cover over differences and awkwardness without the need to dominate attention. Her performance is one of sidelong glances and crooked smiles, enough to impart a wariness as she descends on this journey. Buckley has a natural quality to her, so when her character stammers, stumbling over her words and explanations, you feel her vulnerability on display. After Wild Rose and now this, I think big things are ahead for Buckley. The other actors do credible work with their more specifically daft and heightened roles, mostly in low-key deadpan with the exception of Collette (Hereditary), who is uncontrollably sharing and crying. It’s a performance that goes big as a means of creating alarm and discomfort and she succeeds in doing so.

Buckley (HBO’s Chernobyl) makes for a perfectly matched, disaffected, confused, and plucky protagonist for a Kaufman vehicle. She has a winsome matter of a person trying their best to cover over differences and awkwardness without the need to dominate attention. Her performance is one of sidelong glances and crooked smiles, enough to impart a wariness as she descends on this journey. Buckley has a natural quality to her, so when her character stammers, stumbling over her words and explanations, you feel her vulnerability on display. After Wild Rose and now this, I think big things are ahead for Buckley. The other actors do credible work with their more specifically daft and heightened roles, mostly in low-key deadpan with the exception of Collette (Hereditary), who is uncontrollably sharing and crying. It’s a performance that goes big as a means of creating alarm and discomfort and she succeeds in doing so.

I know there will be people that enjoy I’m Thinking of Ending Things and its surreal, sliding landscape of strange ideas and images. Kaufman is a creative mind like few others in the industry and I hope this is the start of an ongoing relationship with Netflix that affords more of his stories to make their way to our homes. This is only the second movie he’s written to be produced in the last decade, and that’s far too few Kaufman movies to my liking. At the same time, I’m a Kaufman fan and this one left me mystified, alienated, and simply bored. I imagine a second viewing would provide me more help finding parallels and thematic connections, but honestly, I don’t really want to watch this movie again. I recall 2017’s mother!, an unfairly derided movie that was also oft-putting and built around decoding its unsubtle allegory. That movie clicked for me once I attuned myself to its central conceit, and it kept surprising me and horrifying me. It didn’t bore me, and even its indulgences felt like they had purpose and vision. I guess I just don’t personally get that same feeling from I’m Thinking of Ending Things. It’s a movie that left me out cold.

Nate’s Grade: C

You must be logged in to post a comment.