Blog Archives

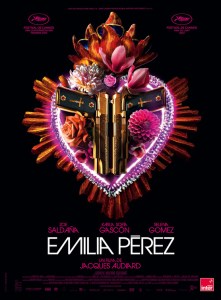

Emilia Perez (2024)

Movie musicals can be sweeping, invigorating, and at their very best transporting, They mingle the high-flying fantasies and visual potential of the cinema, and we’ve gone through many waves of kinds of musicals. Today, we’re in an outlandish world of the outlandish musical, an experience in ironic air 210quotes, where stories that you never would have thought could be musicals would then dare to be different and attempt to be musicals. The much-anticipated Joker sequel, Folie a Deux, dares to be a challenging jukebox musical of old favorites. The French movie Emilia Perez tells the story of a cartel leader that undergoes a sex change and tries to do good with her second life. Both movies are deeply interesting messes as well as experiences I don’t think work as musicals.

In contrast, Netflix’s Emilia Perez is like an entire season of a telenovela streamlined into a two-hour-plus movie that manages to also, for better or worse, be a musical. It is filled with many outlandish and provocative elements you would never expect to be associated with singing and dancing, like a sex change surgery center. This movie mixes so many genres and tones that at one point it feels like you’re watching a crime thriller about Mexican cartels and their manipulation of those in power, and then the next moment it feels like you’re watching an absurd rendition of Mrs. Doubtfire, where a spouse has adopted a new identity and uses this to spend time with their kids they otherwise would not be able to do so. It’s a wild film-going experience; I can’t recall too many musicals that use street stabbings in syncopation with percussion. Because of its go-for-broke ambitions and veering tones, Emilia Perez is destined to be a cult movie, some that fall in love with its bizarre mishmash of elements, but most will probably be stupefied by the entire experience and questioning why, exactly, this was made into a musical.

In Mexico City, Rita Castro (Zoe Saldana) is a savvy defense lawyer tired of living in the shadows of her buffoonish bosses that rely upon her writing prowess to win cases. Someone sees great potential with her, and it happens to be Manitas del Monte (Karla Sofia Gascon), the head of a dangerous cartel. He wants Rita to find the international means to finish the process of Manitas surgically becoming a woman. Under the gun, metaphorically and literally, Rita finds the doctors who will transform the dangerous him into a new her. Manitas then fakes their death, leaving his old life behind to start anew, including their children and wife, Jessi (Selena Gomez). Manitas becomes the titular Emila Perez, but rather retire in luxury, she wants to do good, and Emilia begins a non-profit organization that exhumes bodies, victims from the cartels, to provide closure for their widows and grieving families. Emilia then invites Jessi and their kids to come live in her estate, explaining she is a formerly unknown “aunt” to Manitas. Now Rita is trying to run Emilia’s organization, keeps Emilia from going too far in revealing her identity, and looking out for her own sake considering she’s one of the few that knows about a life before Emila Perez.

I know there will be hand-wringing and cultural tut-tut-ing about the movie’s implicit and explicit themes dealing with trans issues, exploring one woman’s exploration of self and securing the identity she’s always wanted through the lens of a lurid soap opera trading in stereotypes. It’s a lot of movie to digest, and while it feels entirely sincere in every one of its strange creative decisions, it’s also the kind of movie whose tone can invite snickers or derision, like the sex change clinic where a heavily bandaged chorus repeats words like, “vagioplastia” and “penoplastia.” It’s a movie with extreme feelings to go along with its extreme plot turns, but the whole movie feels like it’s trying to settle on a better calibrated wavelength of melodrama.

I think this could have been significantly improved by director/co-writer Jacques Audiard (Rust and Bone, A Prophet) had he embraced more of the movie’s outlandish reality breaking through. Too few of the musical numbers actually do something more than witness someone singing. The opening number, one of the best, involves Rita trying to compose a defense through the streets of Mexico City, while a crowd sweeps around her, often stopping to chime in as an impromptu chorus, sometimes setting up props for her use. It’s a great kickoff, the energy crackling, and I was looking forward to what the rest of the movie could offer. There’s only one other musical number that recreates this significant energy and engagement, a fundraising dinner for Emilia’s organization amongst the powerful members of society. While Emilia speaks at a podium, Rita struts around the floor, sashaying between the tables, and informing the audience about all the dirty deeds and skeletons of the assembled muckety-mucks. She’s literally manhandling the frozen participants, dancing atop their tables in defiance, and it’s a magnificent moment because of how it breaks from our reality to lean into the storytelling potential of musicals. These sequences work so well that it’s flabbergasting that Audiard has, essentially, settled for far less creatively for too much of his movie’s staging. The big Selena Gomez song is just her listlessly singing to the camera while shifting her weight while standing, like the laziest music video of her career. Why tease the audience with the crazy heights as a musical if you’re unwilling?

And now let’s tackle the music, which to my ears was too often rather underwhelming.It sounds like temp music that was intended to be replaced and never was. It’s lacking distinct personality, catchy or memorable melodies, anthems and themes, the things that make musicals enjoyable. The best songs also happen to be the best staged sequences, both involving Rita. These songs have a different vivacious energy by incorporating a hip-hop style of syncopation. “El Mar,” the song during the fundraising dinner, offers an infectious chorus adding extra percussive elements like people slamming fists down onto tables, listening to plates and glasses rattle. These are the moments that enliven a musical and convey its style and panache. Alas, too many of the songs lack that vitality, and can best be described as blandly competent and too readily forgettable.

It’s a shame because Saldana is giving her finest screen performance to date (to be fair, I never watched her Nina Simone biopic). The actress best known for being the strong warrior in sci-fi franchises like Avatar, Guardians of the Galaxy, and Star Trek plays an intriguing character with a rising fire of purpose and paranoia. Early on. Rita is ambitious but unhappy, practically dowdy in appearance, and she begins to come alive under her new role for Emilia. Saldana is electric as she sings and dances and slips effortlessly between Spanish and English, possibly to her first Oscar nomination. She’s the standout, which is slightly strange considering the role of Emilia Perez should be the breakout. Gascon, a trans actress, is quite good in such an outsized role, and gets to play her pre-transitioned identity as well under gobs of masculine makeup and tattoos. The fault isn’t with Gascon’s performance, the issue is that her character has such amazing potential but feels criminally underdeveloped. There is a world of issues of self-identity, culture, repression, shame, anger, jealousy, desire, to name but a few, that could be richly explored from the perspective of the leader of a deadly gang wanting to become a woman. The character is left too inscrutable for my tastes, leaving behind so much unobserved drama. As a result, even though the movie is literally named after her, Emilia Perez feels like a projection more than a character, and if that was indeed the point, then we needed more conflict about that friction.

Emilia Perez is a lot of things all at once; campy, ridiculous, sincere, crazy. It’s messy but it’s an admirably ambitious mess, one that even the faults can be the unexpected charms for someone else. I didn’t fall in love with this genre-bending experiment, although I found portions to be fascinating and others to be confounding. I don’t even think the musical aspects were finely integrated and explored, and so they feel like more of a gimmick, a splashy attempt to marry the high-art of musical theater with the perceived lower-art of grisly crime thrillers and melodrama. It earns marks for daring but the execution is haphazard and scattershot at best. There are moments that elevate the material, where the musical elements feel confidently integrated and supported with the dramatic sequence of events, providing an unexpected and rousing response. However, those moments are few and far between, and the absence only further cements what could have been. Emilia Perez might be your worst movie of the year, a grave miscalculation in tone and storytelling, or it might be a transporting and wild experience, one that can lock up multiple Academy Award combinations for its artistic bravura, a middle-aged Frenchman telling the story of trans empowerment through the guise of a Spanish-speaking musical framework. It sounds like so much and yet paradoxically I was left disappointed that it wasn’t more.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Downhill (2020)/ Force Majeure (2014)

I’ve been meaning to watch 2014’s Force Majeure for some time but it was one of those movies that just fell behind and got trapped by the ever-increasing backlog of “to see” films. Then I discovered that there was to be an American remake by the Oscar-winning writing team behind The Descendants and I decided now would be a good time to go back to Force Majeure. But I purposely chose not to watch the Swedish original until after having watched the American remake, Downhill, to delay prejudicing myself. Both movies have value as cringe comedies prodding fragile masculinity, though the Swedish import runs more with the cascading consequences and the English remake plays more broadly with its big stars.

I’ve been meaning to watch 2014’s Force Majeure for some time but it was one of those movies that just fell behind and got trapped by the ever-increasing backlog of “to see” films. Then I discovered that there was to be an American remake by the Oscar-winning writing team behind The Descendants and I decided now would be a good time to go back to Force Majeure. But I purposely chose not to watch the Swedish original until after having watched the American remake, Downhill, to delay prejudicing myself. Both movies have value as cringe comedies prodding fragile masculinity, though the Swedish import runs more with the cascading consequences and the English remake plays more broadly with its big stars.

Both movies follow families on skiing vacations where the father (Johannes Kuhnke as Tomas, Will Ferrell as Pete) abandon their wives (Lisa Loven Kongdli as Ebba, Julia Louis-Dreyfus as Billie) and children when an approaching avalanche looks to be imminently deadly. It proves to be harmless but the scare it created was very real, and the damage to this family is also very real. In their dire moment of need, as death looked increasingly possible, this family watched its patriarch run away to save himself (and not before grabbing his phone). The father denies running away, finding his own slippery slope of excuses to pretend and convince his family that everything is still the same.

Downhill takes the very specific tone of the Swedish original by writer/director Ruben Ostlund (The Square) and plays it safer and more broadly. There’s an added context of the ski lodge being a couple’s resort with the idea of horny and available alternatives just a slope away for fun. The movie is practically throwing a more traditionally “manly” and virile romantic candidate at Billie and it’s so obvious and immediate that it reminded me of the sexy yoga instructor from 2009’s Couples Retreat, another movie that involved a holiday retreat with two camps, one more family-friendly and another more hedonistic. It feels too convenient and crass to immediately present our heroine with prime cheating options and have her question her own fidelity. In Force Majeure, one of the best and most awkward moments occurs when Tomas tries to portray himself as an equal victim to his own shortcomings as a man. He lists several faults, including infidelity, that don’t phase his wife, which implies she is well aware of this man’s flaws. It’s such a pathetic moment of emotional manipulation that incredulous laughter is the only natural response, and the movie makes the viewer stay in that uncomfortable squirm. Tomas lays on the floor wailing like a child, which then triggers his children to come out and lay upon their weeping father and then admonish their mother to follow their supportive lead. It’s a hilarious moment and borne from the organic developments tied to character relationships. In Downhill, by contrast, we get stuff like the sexy ski instructor and a really horny, handsy lodge lady (Miranda Otto, in thick accent).

Downhill takes the very specific tone of the Swedish original by writer/director Ruben Ostlund (The Square) and plays it safer and more broadly. There’s an added context of the ski lodge being a couple’s resort with the idea of horny and available alternatives just a slope away for fun. The movie is practically throwing a more traditionally “manly” and virile romantic candidate at Billie and it’s so obvious and immediate that it reminded me of the sexy yoga instructor from 2009’s Couples Retreat, another movie that involved a holiday retreat with two camps, one more family-friendly and another more hedonistic. It feels too convenient and crass to immediately present our heroine with prime cheating options and have her question her own fidelity. In Force Majeure, one of the best and most awkward moments occurs when Tomas tries to portray himself as an equal victim to his own shortcomings as a man. He lists several faults, including infidelity, that don’t phase his wife, which implies she is well aware of this man’s flaws. It’s such a pathetic moment of emotional manipulation that incredulous laughter is the only natural response, and the movie makes the viewer stay in that uncomfortable squirm. Tomas lays on the floor wailing like a child, which then triggers his children to come out and lay upon their weeping father and then admonish their mother to follow their supportive lead. It’s a hilarious moment and borne from the organic developments tied to character relationships. In Downhill, by contrast, we get stuff like the sexy ski instructor and a really horny, handsy lodge lady (Miranda Otto, in thick accent).

That’s not to say the remake doesn’t find effective ways to make the most of its American infusion. There’s a scene where Pete and Billie are complaining to the ski lodge staff because someone must account for their perceived injury. The moment doesn’t go as they hoped and the security head (Game of Thrones’ Kristofer Hivju) refuses to apologize or admit any wrong. He points out all the warnings that the American couple somehow missed, and this only causes Billie to grow in her impotent agitation. It’s a moment that plays to the ugly American stereotype of self-absorption and the insistence to be heard. This scene would not have worked with the Force Majeure characters at all. Billie is a more interesting character and given more ambiguity and flaws than Ebba, who is often the perplexed voice of the audience. There are adaptation changes and new jokes that work for Downhill but more often it doesn’t explore the comic avenues open to it (hashtag jokes… really?). The best jokes are frequently holdovers.

Something I enjoyed exclusively about Force Majeure was how it widened its scope to include the contagious nature of questioning masculine assumptions. The supporting characters have more significance than in Downhill. Tomas’ friend, Mats (Game of Thrones’ Kristofer Hivju), begins as an awkward lifeline trying to offer meager supportive explanations to his beleaguered friend’s cowardice (“You ran away so that you could come back and dig everyone out, right?”) and then he too is negatively affected. His much younger girlfriend begins to look at him differently and with suspicion, wondering if he too would disappoint when under a similar life-threatening scenario. She questions whether it’s simply a generational divide and an older generation (Mats) just doesn’t feel as brave and selfless. This eats away at Mats and wreaks havoc with his relationship. You too might consider how well you really know your loved ones and how you might respond as well. It’s such a wonderful what-if scenario to apply to one’s self. This contagious nature of doubt makes the story feel that much more interesting when one man’s failings can spiral outward and ensnare others. This deepened the dark comedy and provided interesting and complimentary side characters. With Downhill, we don’t really get any other characters on the same level of consideration as our main couple, Pete and Billie.

The children actually play a bigger role in Downhill as the relationship between the sons and their father is on the brink. They see him decidedly different and Pete spends time trying to regain their favor and trust and, naturally, failing. With Force Majeure, the children are kept on the sidelines and they’re more worried that mom and dad may be doomed to a divorce rather than being upset or disappointed with their father. Downhill clearly aligns the sons with their mother and has Billie call upon them to provide corroborating testimony to her account in one deliciously awkward extended moment. It’s one area where Downhill bests its source material but again that’s because it also dramatically scales down the importance of supporting adults.

The children actually play a bigger role in Downhill as the relationship between the sons and their father is on the brink. They see him decidedly different and Pete spends time trying to regain their favor and trust and, naturally, failing. With Force Majeure, the children are kept on the sidelines and they’re more worried that mom and dad may be doomed to a divorce rather than being upset or disappointed with their father. Downhill clearly aligns the sons with their mother and has Billie call upon them to provide corroborating testimony to her account in one deliciously awkward extended moment. It’s one area where Downhill bests its source material but again that’s because it also dramatically scales down the importance of supporting adults.

Ferrell (Holmes & Watson) and Louis-Dreyfus (Veep) are such an enjoyable comedy pairing and work together smoothly for Downhill’s broader aims. The Swedish actors are far more subdued, understated, and dry, dissolving into playing mundane, regular folk. You’re not going to get that with Ferrell especially. His big screen buffoon tendencies play well for Pete’s blustery self-deluded narcissism, but he lacks the bite for the destructive self-pity that emboldened Kuhnke. Ferrell’s performance is more restrained than you might assume but he still doesn’t feel like the right fit for the character and where he needs to go. He never stops being seen as Ferrell. Louis-Dreyfus is such a pro and is able to navigate the bleaker comedy with great precision. Her shaken monologue retelling the avalanche incident and pausing on “… to die, I guess” had me rolling.

Downhill is over 30 minutes shorter and yet it feels stretched thin, circling the same comic points, which can make the film feel frustratingly smaller in scope and ambition. The endings are different and come across a similar message over never knowing how a person may respond in the middle of danger. Force Majeure concludes with a scenario that allows its wounded males to save some honor and the women to question their own responses, a paradigm shift of gender expectations. The triumphant recapturing of masculinity builds to its own satirical breaking point, ready to laugh at Tomas feeling like a ridiculous John Wane-style cowboy. In contrast, the American ending doesn’t feel as rich or as earned as its predecessor.

Downhill is an accessible and funny remake that has some smart deviations from its source material to deliver its own version, and sometimes it feels like the filmmakers want to make a much more mainstream comedy. The tonal identity issues sap the comedic and dramatic momentum of the story, which can make the overall film frustrating and unsatisfying at times while you wait for it to settle. Then its 85 minutes are over and it’s done. Force Majeure, on the other hand, is the most confident, strident, and awkward viewing, not to mention longer viewing at two hours in length. It’s actually too long and with a few segments that could be trimmed or removed entirely (drone flying, the first set of friends, getting lost in a snowy fog). There’s even a running joke where the gag is simply that the ski lifts and moving sidewalks are just super slow. The movie takes its understated, dry comic sensibility even to its relaxed sense of pacing. Both movies are funny and emphasize different aspects of the premise of the consequences of cowardice. I likely would have enjoyed Downhill less had I seen Force Majeure first but it’s still a decent American remake for something that was so calculating and exact in tone, a laugh-out-loud comedy that doesn’t play like a comedy. Still, co-writers/directors Jim Rash and Nat Faxon (The Way Way Back) have enough skill and polished instinct that even a less sophisticated, more obvious version of Force Majeure is still entertaining enough. It might lack some of the edge of the original but Downhill is an agreeable comedy of disagreeable decisions.

Downhill is an accessible and funny remake that has some smart deviations from its source material to deliver its own version, and sometimes it feels like the filmmakers want to make a much more mainstream comedy. The tonal identity issues sap the comedic and dramatic momentum of the story, which can make the overall film frustrating and unsatisfying at times while you wait for it to settle. Then its 85 minutes are over and it’s done. Force Majeure, on the other hand, is the most confident, strident, and awkward viewing, not to mention longer viewing at two hours in length. It’s actually too long and with a few segments that could be trimmed or removed entirely (drone flying, the first set of friends, getting lost in a snowy fog). There’s even a running joke where the gag is simply that the ski lifts and moving sidewalks are just super slow. The movie takes its understated, dry comic sensibility even to its relaxed sense of pacing. Both movies are funny and emphasize different aspects of the premise of the consequences of cowardice. I likely would have enjoyed Downhill less had I seen Force Majeure first but it’s still a decent American remake for something that was so calculating and exact in tone, a laugh-out-loud comedy that doesn’t play like a comedy. Still, co-writers/directors Jim Rash and Nat Faxon (The Way Way Back) have enough skill and polished instinct that even a less sophisticated, more obvious version of Force Majeure is still entertaining enough. It might lack some of the edge of the original but Downhill is an agreeable comedy of disagreeable decisions.

Nate’s Grades:

Force Majeure: B+

Downhill: B-

Persepolis (2007)

Marjane Satrapi has, by all accounts, a very unique life. Growing up under the repression of the Islamic Revolution, she settled in France and created a series of acclaimed best-selling graphic novels called Persepolis, based upon her life growing up in and out of Iran. The movie was France’s official entry for the 2007 Foreign Language Oscar, bypassing the equally lauded and inventive Diving Bell and the Butterfly. And yet Persepolis did not even make the short list of nine nominees, which eventually gets parred down to five (neither did 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, which WON the Best Film from the European Film Awards, over other movies that managed to make the Academy’s five nominees). I consider this a glaring omission. How could anyone not be entranced by Satrapi and co-director Vincent Paronnaud’s masterwork?

Marjane Satrapi has, by all accounts, a very unique life. Growing up under the repression of the Islamic Revolution, she settled in France and created a series of acclaimed best-selling graphic novels called Persepolis, based upon her life growing up in and out of Iran. The movie was France’s official entry for the 2007 Foreign Language Oscar, bypassing the equally lauded and inventive Diving Bell and the Butterfly. And yet Persepolis did not even make the short list of nine nominees, which eventually gets parred down to five (neither did 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, which WON the Best Film from the European Film Awards, over other movies that managed to make the Academy’s five nominees). I consider this a glaring omission. How could anyone not be entranced by Satrapi and co-director Vincent Paronnaud’s masterwork?

In Tehran, the capital of Iran, young Marjane and her family watch as rebellious forces overthrow the Shah in 1979. The Shah was the ruler of Iran and could readily be described as a dictator. He was friendly to Western countries and wanted Iran to follow their lead. Large forces unified and deposed the Shah, setting the stage for Iran to have its own system of rule that the people would decide upon. Marjane’s father swings her around in his arms and excitedly proclaims that democracy has come to his country at last. Landslide numbers “vote” for radical Islamic leaders to take control of the government, and Iran becomes a militant theocracy. Privileges and reforms are revoked, and women will have to wear long burquas and veils to be righteous. Marjane is too outspoken and her parents, fearing for her safety, send her to Europe to be educated. While she is absent Iraq attacks Iran and the countries are engulfed in a decade-long border war.

Persepolis is a gem of a movie, at once a personal coming-of-age account that manages to be fascinating and honest and also a universal tale of struggle for cultural identity. The evocative black and white animation is a joy to watch. The crisp drawing style manages to express so much with the seemingly simple, clean images. At times the visuals take on a lovely German expressionistic feel, and the world feels like it is made out of folded layers of paper. I would fall in love with a movement, a facial expression, that fact that smiles look like boomerangs, something small yet immeasurably enjoyable that struck a deep chord inside me. The arresting black and white visuals do not distract from the story in any way, in fact they help to mirror the repressive nature of what befalls Iran. A silhouetted group of protesters is shot at and one of them falls to the ground. Great inky blackness seeps out of the fallen body and merges with the rest of the screen, adding emotional heft that color could never capture.

Persepolis is a gem of a movie, at once a personal coming-of-age account that manages to be fascinating and honest and also a universal tale of struggle for cultural identity. The evocative black and white animation is a joy to watch. The crisp drawing style manages to express so much with the seemingly simple, clean images. At times the visuals take on a lovely German expressionistic feel, and the world feels like it is made out of folded layers of paper. I would fall in love with a movement, a facial expression, that fact that smiles look like boomerangs, something small yet immeasurably enjoyable that struck a deep chord inside me. The arresting black and white visuals do not distract from the story in any way, in fact they help to mirror the repressive nature of what befalls Iran. A silhouetted group of protesters is shot at and one of them falls to the ground. Great inky blackness seeps out of the fallen body and merges with the rest of the screen, adding emotional heft that color could never capture.

Told for long stretches from the perspective of a child, Persepolis manages to find unique perceptions. The child point of view allows the film to unfold naturally with innocence and inquisitiveness, qualities that would soon be hard to recapture once the promise of revolution turned sour. Young Marjane feels jealous and competitive that her cousin can brag that her father spent more time as a political prisoner. It’s an odd stance for an adult and yet it feels entirely within reason for children. Marjane deals with issues she cannot fully understand as a child but she tries her best. The eyes of children also let the filmmakers mingle with the fantastic. Marjane speaks to God at points, and after a horrible tragedy God is trying to apologize and explain but little Marjane will not hear any of it. She orders God to leave her and so He departs. A little girl turning her back on God will hit you is the kind of devastating stuff that can put a permanent lump in your throat.

I was dumbfounded at the emotional depths the film plumbs in a scant 95 minutes. This is an incredibly powerful tale, richly told with poignant insights and grace. There were several times I was overcome with emotion and had to dab my eyes. Satrapi achieves great emotional resonance with minute details, making the film exciting in how engaging it continues to be from beginning to end. Marjane’s relationship with her family anchors the movie and you can feel the power of their love and bonds. Imprisoned uncles who spouted communist dogma are released only to be seen as a danger once again. Marjane’s mother is worried when Marjane keeps showing a fiery outspoken spirit. One day she shakes a teenage Marjane, screaming at her the horrid possibilities that can happen to women under this regime. She cites one teenage girl who was executed, but they don’t believe in killing virgins, so the guards took care of that bothersome roadblock. Marjane’s mother is wild-eyed with fear and what might await her little girl, and her gnawing concern is resoundingly powerful. Marjane’s grandmother serves as her emotional compass throughout her life. Grandma stresses that Marjane should be proud of her cultural identity and stay true to herself. When Marjane gets older she hears her grandmother’s voice to set her straight in times of doubt.

But while the movie can be heartwarming, it does not fall victim to sticky sentimentality. Satrapi deals with some harsh truths about life in Iran and also her time in Europe as a blossoming woman without a country. She doesn’t sugarcoat reality and Marjane’s parents make it a point to be up front with their daughter about what is happening; an uncle tells little Marjane, before he is executed, that knowledge must live on and she, the youth, must be the one to keep it alive. The Iran-Iraq war ends in a stalemate with millions in casualties. Persepolis details life behind the veil and the shift the country took to radical Islamic rule but the film isn’t all doom and gloom. There’s a natural curiosity about a story of a girl who becomes a woman in a repressive society. Marjane’s spiky rebellious spirit makes for genuinely human comedy. She shops for Iron Maiden tapes on the Iranian black market, wears a jacket that states, “Punk is not ded,” and screams with joy at ripping her veil off during a car ride and letting the wind gust through her hair. There is a bounty of humor to be found in unexpected places. Marjane is running to catch a bus and is stopped by two policemen who complain that when she runs her butt moves “in an obscene way.” She simmers and finally yells, “Then stop staring at my ass!”

But while the movie can be heartwarming, it does not fall victim to sticky sentimentality. Satrapi deals with some harsh truths about life in Iran and also her time in Europe as a blossoming woman without a country. She doesn’t sugarcoat reality and Marjane’s parents make it a point to be up front with their daughter about what is happening; an uncle tells little Marjane, before he is executed, that knowledge must live on and she, the youth, must be the one to keep it alive. The Iran-Iraq war ends in a stalemate with millions in casualties. Persepolis details life behind the veil and the shift the country took to radical Islamic rule but the film isn’t all doom and gloom. There’s a natural curiosity about a story of a girl who becomes a woman in a repressive society. Marjane’s spiky rebellious spirit makes for genuinely human comedy. She shops for Iron Maiden tapes on the Iranian black market, wears a jacket that states, “Punk is not ded,” and screams with joy at ripping her veil off during a car ride and letting the wind gust through her hair. There is a bounty of humor to be found in unexpected places. Marjane is running to catch a bus and is stopped by two policemen who complain that when she runs her butt moves “in an obscene way.” She simmers and finally yells, “Then stop staring at my ass!”

If Persepolis has any shortcomings it’s that the narrative peaks a bit too early. Seeing a child come of age during the Islamic Revolution is generally more interesting than watching a teenager navigate unfaithful boyfriends in Europe. Persepolis never stops being entertaining or relevant, it just so happens that the greater emotional rewards are tied to life and family in Iran.

Persepolis is a marvelously moving and unique coming-of-age tale set against a unique time. Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novels have fluidly been translated into a film that resonates with great emotional turmoil and inspiration. The alluring black and white visuals and clean animation style dazzle the eyes, while the enthralling personal story reaches deep inside and touches the heart. The film is brilliant, beautiful, harrowing, deeply human, fascinating, and ultimately inspiring. It’s rare to find a movie that can hit so many emotions with finesse, animated or live action. Persepolis is a bold vision and a revealing and lovely film that I cannot wait to revisit often. This is more than just a cartoon, folks. This is art.

Nate’s Grade: A

You must be logged in to post a comment.