Blog Archives

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) [Review Re-View]

Originally released March 19, 2004:

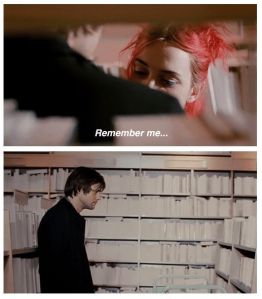

No other movie this year captured the possibility of film like Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman’s enigmatic collaboration. Eternal Sunshine was a mind-bending philosophical excursion that also ended up being one of the most nakedly realistic romances of all time. Joel (Jim Carrey restrained) embarks on having his memories erased involving the painful breakup of Clementine (Kate Winslet, wonderful), an impulsive woman whose vibrant hair changes as much as her moods. As Joel revisits his memories, they fade and die. He starts to fall in love with her all over again and tries to have the process stop. This labyrinth of a movie gets so many details right, from the weird physics of dreams to the small, tender moments of love and relationships. I see something new and marvelous every time I watch Eternal Sunshine, and the fact that it’s caught on with audiences (it was nominated for Favorite Movie by the People’s friggin’ Choice Awards) reaffirms its insights into memory and love. I never would have thought we’d get the perfect romance for the new millennium from Kaufman. This is a beautiful, dizzingly complex, elegant romance caked in visual grandeur, and it will be just as special in 5 years as it will be in 50, that is if monkeys don’t evolve and take over by then (it will happen).

Nate’s Grade: A

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

“How happy is the blameless vestal’s lot!

The world forgetting, by the world forgot:

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind!

Each prayer accepted, and each wish resigned;”

-Alexander Pope, Eloisa to Abelard (1717)

“Go ahead and break my heart, that’s fine

So unkind

Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind

Oh, love is blind

Why am I missin’ you tonight?

Was it all a lie?”

-Kelly Clarkson, Mine (2023)

This one was always going to be special. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is not just one of my favorite movies, it’s one of those movies that occupies the place of Important Formative Art. It’s a movie that connected with me but it’s also one that profoundly affected me and changed me, that inspired me in my own creative ventures. With its elevated place in my memory, I’ll also admit that there was some mild trepidation about returning to it and having it not measure up to the impact it had all those twenty years ago. It’s impossible to recreate that first experience or to chase after it, but you hope that the art we consider great still has resonance over time. This happened before when I revisited 2000’s Requiem for a Dream, a movie that gobsmacked me in my youth, had such innate power and fascination, and had lessened over the decades. It was still good art but it wasn’t quite the same, and there’s a little tinge of disappointment that lingers.

When I saw the movie for the first time it was at a promotional screening. I was a senior in college and had dyed my hair bright red for the second time. After marveling over my first encounter with 1999’s Run Lola Run, I was determined to have hair like the titular Lola. My parents were hesitant and set parameters, like certain grade achievements, and I met them all. Afterwards they had nothing left to quibble so I dyed my hair red, as well as other colors, my sophomore year and then again my senior year. At the screening, a publicist for the studio asked if I wanted to compete for a prize. I demurred but then she came back and asked again, and sensing something to my advantage, I accepted. It turns out the pre-show contest was a Clementine (Kate Winslet) look alike contest and my only competition was a teen girl with one light swath of blue hair. The audience voted and I won in a landslide and was given a gift basket of official Eternal Sunshine merchandise that included the CD soundtrack and a bright orange hooded sweatshirt modeled after the one Clem wears in the movie. That sweatshirt quickly became one of my favorite items of clothing, something special that nobody else had from a movie I adored. I wore it everywhere and it became a comfort and a confidence builder. Back during my initial courtship with my wife, in the winter months of 2020, she held onto the orange hoodie as a memento to wear and think of me during our time apart. She said it even smelled like me, which was a comfort. It had meaning for us, and we cherished it. I had to marry her, of course, to ensure I’d eventually get the sweatshirt back in my possession (I kid).

The lessons of Eternal Sunshine run deep for me. On the surface it’s a breakup movie about an impulsive woman, Clem, deciding to erase her memories of her now ex-boyfriend Joel (Jim Carrey). Out of spite, he elects to have the same procedure, and from there we jump in and out of Joel’s head as a subconscious avatar experiences their relationship but in reverse. It’s the bad memories, the hurt and ache of a relationship nearing or past its end, but as each memory degrades and Joel goes further into the past, he discovers that there are actually plenty of enjoyable memories through those good times, the elation and discovery, the connections and development of love, that he doesn’t want to lose. He tries to fight against the procedure but it becomes a losing battle, and so he gets to ride shotgun in his cerebellum as this woman vanishes from his life. What began out of spite and heartache ends in mourning and self-reflection.

At its heart, the movie is asking us to reflect upon the importance of our personal experiences and how they shape us into the people that we are. This includes the ones that cause us pain and regret. The human experience is not one wholly given to happiness, unfortunately, but there are lessons to be had in the scars and pain of our individual pasts. I’m not saying that every point of discomfort or pain is worthwhile, as there are many victims who would say otherwise, but we are the sum total of our experiences, good and bad. With enough distance, wisdom can be gained, and perhaps those events that felt so raw and unending and terrible eventually put us on the path of becoming the person you are today. Now, of course, maybe you don’t like the person you are now, but that doesn’t mean you’re also a prisoner to your past and doomed to dwell in misery.

After my divorce from my previous wife in 2012, I wrote a sci-fi screenplay following some of the same themes from Eternal Sunshine. It was about two dueling time travelers trying to outsmart one another, one hired to ensure a romantic couple never got together and one hired to make sure that they had. The characters represented different viewpoints, one arguing that people are the total of their experiences and the other arguing people should be capable of choosing what experiences they want ultimately as formative. Naturally, through twists and turns, the one time traveler learns a lesson about “living in the now,” to stop literally living in the past and trying to correct other people’s perceived mistakes, and that our experiences, and our heartache, can be valuable in putting us into position to being the people we want or living the lives we seek. It shouldn’t be too hard to see that I was working through my own feelings with this creative venture. It got some attention within the industry and I dearly hope one day it can be made into a real movie. It’s one of my favorite stories I’ve ever written and I’m quite proud of it. It wouldn’t exist without Eternal Sunshine making its mark on me all those years ago.

It’s an amazing collaboration between director Michel Gondry and the brilliant mind of Charlie Kaufman. The whimsical, hardscrabble DIY-style of Gondry’s visuals masterfully keeps the viewer on our toes, as Joel’s memories begin vanishing and collapsing upon one another in visually inventive and memorable ways. There’s moments like Joel, after finding Clem once she’s erased her memory of him, and he storms off while row after row of lights shuts off, dooming this memory to the inky void. There’s one moment where he’s walking through a street and with every camera pan more details from the store exteriors vanish. A similar moment occurs through a store aisle where all the paperbacks become blank covers. It’s a consistent visual inventiveness to communicate the fraying memories and mind of Joel, which becomes its own playground that allows us to better understand him. The score by Jon Brion (Magnolia) is also a significant addition, constantly finding unique and chirpy sounds to provide a sense of earned melancholy. By experiencing their relationship backwards, it allows us to have a sense of discovery about the relationship. This is also aided by Kaufman’s sleight-of-hand structure, with the opening sequence misleadingly the beginning of their relationship when it’s actually their second first time meeting one another. The pointed details of relationships, both on the rise and decline, feel so achingly authentic, and the characters have more depth than they might appear on the surface. Joel is far more than a hopeless romantic. Clem is far more than some Manic Pixie Dream Girl, a term coined for 2005’s Elizabethtown. She tells Joel that she’s not some concept, she’s not here to complete his life and add excitement; she’s just a messed up girl looking for her own peace of mind and she doesn’t promise to be the answer for any wounded romantic soul.

The very end is such a unique combination of feelings. After Mary (Kirsten Dunst) discovers that she’s previously had her memories of an affair with her boss erased, she takes it upon herself to mail every client their files so that they too know the truth. Joel and Clem must suffer listening to their recorded interviews where they are viciously attacking one another, like Clem declaring Joel to be insufferably boring who puts her on edge, and Joel accuses her of using sex to get people to like her. Both are hurt by the accusations, both shake them off as being inaccurate, and yet it really is them saying these things, recorded proof about the ruination of their relationship. Would getting together be doomed to eventually repeat these same complaints? Clem walks off and Joel chases after her and tells her not to go. Teary-eyed, she warns that she’ll grow bored of him and resentful because that’s what she does, and she’ll become insufferable to him. And then Joel says, “Okay,” an acceptance that perhaps they may repeat their previous doomed path, maybe it’s inevitable, but maybe it also isn’t, and it’s worth it to try all the same. Maybe we’re not destined to repeat our same mistakes. Then it ends on a shot of our couple frolicing in the snow, the descending white beginning to blot out the screen, serving as a blank slate. It’s simultaneously a hopeful and pessimistic ending, a beautifully nuanced conclusion to a movie exploring the human condition.

Winslet received an Oscar nomination for her sprightly performance, and deservedly so, but it’s Carrey that really surprises. He had already begun to stretch his dramatic acting muscles before in the 1998 masterpiece The Truman Show and the far-from-masterpiece 2001 film The Majestic. He’s so restrained in this movie, perfectly capturing the awkwardness and passive aggressive irritability of the character, a man who views his life as too ordinary to be worth sharing. Clem begs him to share himself since she’s an open book but he’s more mercurial. She wants to get to know him better but to Joel there’s a question of whether or not he has anything worthwhile getting to know. Carrey sheds all his natural charisma to really bring this character to life. It’s one of his best performances because he’s truly devoted to playing a character, not aggressively obnoxious Method devotion like in 1999’s Man on the Moon.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a messy, enlightening, profound, playful, poignant, and mesmerizing movie. A perfect collaboration between artists with unique creative perspectives. I see something new every time I watch it, and it’s already changed my life in different ways. I used to see myself as Joel when I was younger, but then I grew to see him as self-pitying and someone who too often sets himself up for failure by being too guarded and insular. It’s a reminder that our cherished relationships remain that way by allowing ourselves to be vulnerable and open. We are all capable and deserving of love.

Re-View Grade: A

Human Nature (2002) [Review Re-View]

Originally released April 12, 2002:

Originally released April 12, 2002:

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman jumped on to Hollywood’s A-list when his feature debut Being John Malkovich was unleashed in 1999. Malkovich was a brilliant original satire on identity, be it celebrity or sexual, and was filled with riotous humor but also blended beautifully with a rich story that bordered on genius that longer it went. Now Kaufman tries his hand expounding at the meaning of civilization versus animal instinct in Human Nature. As one character tells another, “Just remember, don’t do whatever your body is telling you to do and you’ll be fine.”

Lila (Patricia Arquette) is a woman burdened with excessive body hair ever since she was old enough for a training bra (with the younger version played by Disney’s Lizzie McGuire). Lila feels ashamed by her body and morbidly humiliated. She runs away to the forest to enjoy a life free from the critical eyes of other men. Here she can commune with nature and feel that she belongs.

Nathan (Tim Robbins) is an anal retentive scientist obsessed with etiquette. As a young boy Nathan was sent to his room for picking the wrong fork to eat his meal with. He is now trying his best to teach mice table manners so he can prove that if etiquette can be taught to animals it can be ingrained toward humanity. Lila and Nathan become lovers when she ventures back into the city, eliminating her body hair for now, because of something infinitely in human nature – hormones. The two of them find a form of content, as neither had known the intimate touch of another human being.

Nathan (Tim Robbins) is an anal retentive scientist obsessed with etiquette. As a young boy Nathan was sent to his room for picking the wrong fork to eat his meal with. He is now trying his best to teach mice table manners so he can prove that if etiquette can be taught to animals it can be ingrained toward humanity. Lila and Nathan become lovers when she ventures back into the city, eliminating her body hair for now, because of something infinitely in human nature – hormones. The two of them find a form of content, as neither had known the intimate touch of another human being.

“Puff” (Rhys Ifans) is a grown man living his life in the woods convinced by his father that he is an ape. One day while walking through the woods, Nathan and Lila discover the ape-man and have differing opinions on what should be done with him. Nathan is convinced that he should be brought into civilization and be taught the rules, etiquette, and things that make us “human.” It would also be his greatest experiment. Lila feels that he should maintain his freedom and live as he does in nature, how he feels he should.

What follows is a bizarre love triangle over the reeducation of “Puff,” as Nathan’s slinky French assistant Gabrielle (Miranda Otto) names him. Lila is torn over the treatment of Puff and also her own society induced shame of her abundant amount of body hair. Nathan feels like he is saving Puff from his wayward primal urges, as he himself becomes a victim of them when he starts having an affair with Gabrielle. Puff, as he tells a congressional committee, was playing their game so he could find some action and “get a piece of that.”

Kaufman has written a movie in the same vein as Being John Malkovich but missing the pathos and, sadly, the humor. Human Nature tries too hard to be funny and isn’t nearly as funny as it thinks it is. Many quirky elements are thrown out but don’t have the same sticking power as Kaufman’s previous film. It’s a fine line between being quirky just for quirky’s sake (like the atrocious Gummo) and turning quirky into something fantastic (like Rushmore or Raising Arizona). Human Nature is too quirky for its own good without having the balance of substance to enhance the weirdness further. There are many interesting parts to this story but as a whole they don’t ever seriously gel.

Kaufman has written a movie in the same vein as Being John Malkovich but missing the pathos and, sadly, the humor. Human Nature tries too hard to be funny and isn’t nearly as funny as it thinks it is. Many quirky elements are thrown out but don’t have the same sticking power as Kaufman’s previous film. It’s a fine line between being quirky just for quirky’s sake (like the atrocious Gummo) and turning quirky into something fantastic (like Rushmore or Raising Arizona). Human Nature is too quirky for its own good without having the balance of substance to enhance the weirdness further. There are many interesting parts to this story but as a whole they don’t ever seriously gel.

Debut director Michel Gondry cut his teeth in the realm of MTV making surreal videos for Bjork and others (including the Lego animated one for The White Stripes). He also has done numerous commercials, most infamously the creepy-as-all-hell singing navels Levi ad. Gondry does have a vision, and that vision is “Copy What Spike Jonze Did as Best as Possible.” Gondry’s direction never really registers, except for some attractive time shifts, but feels more like a rehash of Jonze’s work on, yep you guessed it, Being John Malkovich.

Arquette and Robbins do fine jobs in their roles with Arquette given a bit more, dare I say it, humanity. Her Lila is trapped between knowing what is true to herself and fitting into a society that tells her that it’s unhealthy and wrong. Ifans has fun with his character and lets it show. The acting in Human Nature is never really the problem.

While Human Nature is certainly an interesting film (hey it has Arquette singing a song in the buff and Rosie Perez as an electrologist) but the sum of its whole is lacking. It’s unfair to keep comparing it to the earlier Malkovich but the film is trying too hard to emulate what made that movie so successful. Human Nature just doesn’t have the gravity that could turn a quirky film into a brilliant one.

Nate’s Grade: C+

——————————————————

WRITER REFLECTIONS 20 YEARS LATER

I’m at a loss with 2002’s Human Nature. I thought in the ensuing twenty years I would have more to say with coming back to the early burst of brilliant writer Charlie Kaufman in the immediate wake of his successful debut, 1999’s Being John Malkovich. 2002 was a big year for Kaufman; he had three movies released that he wrote, all of them wildly different. His best work was Adaptation, a reteaming with Malkovich’s Oscar-nominated director Spike Jonze, that earned Chris Cooper a Best Supporting Actor Oscar and Kaufman was close to winning for Best Original Screenplay and sharing the honor with his pretend twin brother, the both of whom were portrayed by Nicolas Cage. It was the most challenging and creative and fulfilling of the three. There was also Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, the debut for George Clooney as a director, was a lark of a movie, taking Gong Show host Chuck Barris’ “unauthorized autobiography” where he claimed he was doubling as a CIA black ops hitman. I recently re-watched this one months ago and my opinion even lowered because there’s nothing to the movie beyond the central irony of the unexpected reality of this unexpected man being a spy and assassin. There’s no real insight into Barris as a character and he comes across as scummy and unworthy of a big screen examination. It’s a story that only exists to be ironic and missing the messy humanity and pathos of Kaufman’s best.

But Kaufman’s most forgotten movie in his screenwriting career is definitely Human Nature, the debut film for Michel Gondry, one of Kaufman’s other collaborators along with Jonze, both men having gained great acclaim for eclectic and visionary and just plain weird music videos. It follows three main characters, each debriefing their tale to an audience. Lila (Patricia Arquette) is accused of murder and discussing her lifelong malady of growing intense amounts of body hair, enough so that she worked as a gorilla woman in a circus sideshow. Puff (Rhys Ifans) is a man raised in the wild who intended to be an ape and returned to society, been trained in etiquette, and become an example of the transformative power of civilization. Dr. Nathan Bronfman (Tim Robbins) is telling his story after death with a bullet hole in the middle of his pasty forehead, as the scientist who found Puff, trained him, and romanced Lila before cheating on her with his French assistant (Miranda Otto). Immediately, the movie presents questions for us to unpack: how did Nathan die? Who was really responsible? What will be the connections between these three very different characters? Then there are assorted kooky side characters that come in and out, but the focus is mostly on this trio, perhaps a foursome with Otto, and the shame is that there is only one really interesting character among them.

Lila is the only protagonist worth following. She feels like a freak, even served in a “freak show,” and must hide her secret from lovers who would object to her untamed mane. She’s vulnerable and hopeful but pressured to conform to be accepted, and her journey to radical self-acceptance would have been an entertaining movie all on its own. However, by fragmenting the narrative with Puff and Nathan, she gets far less attention and her story becomes, for far too long, just her willfully sublimating herself to Nathan’s standards of beauty. Lila frustratingly feels like a character furiously trying to do whatever she can to keep the affections of a bad man. It’s reductive to the movie’s most interesting character. Puff and Nathan, in contrast, just feel like ideas, opposite poles in a discussion over the differences between animal instinct and the ideals of human civilization in all its hypocritical splendor. Even though both men are given comic-tragic back-stories, neither is really a richly defined character. Puff is all impulses and his urges become a tiresome comic device when we watch him hump somebody or something for the eightieth time. Nathan’s preoccupation with social niceties is meant to be absurd (teaching table manners to mice?) and petty, a meaningless articulation of “high culture and values.” I did laugh out loud when Nathan was teaching Puff how to respond at the opera, complete with a constructed box seat. Nathan is a satirical punching bag for a bourgeois sensibility. Neither him nor Puff feel like characters, instead more like conflicting points of view of humanity.

The other disappointing aspect to Human Nature is as I declared in 2002, it feels like quirky for quirky’s sake screenwriting. Kaufman has become a screenwriting legend and he’s able to marry absurd, bizarre, and dangerous elements into meaningful and subversive and satirical masterstrokes, but the man cannot be expected to perform at the highest heights every time. Human Nature is stuffed full of wacky moments and wacky characters and it doesn’t feel like it ever amounts to more than the sum of its transitory parts. In contrast, 2022’s Everything Everywhere All At Once is an example of how one can take the most bizarre ideas and still find ways to tie them back in meaningful ways that braid into the larger theme. However, much of Human Nature feels like a quirk dartboard being hit over and over, a catalog of strange visuals and goofy ideas (Lila breaks out into song!) that fails to coalesce into a larger thesis like an Adaptation or an Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind or the vastly underrated Synecdoche, New York, Kaufman’s directorial debut. He’s a master of the idiosyncratic, but Human Nature suffers because ultimately what does it have to say? Puff is set up for ridicule. Nathan is set up for ridicule. Even Lila is set up, though for murder. In the end, when Puff returns to the wild in a public galivanting that feels like a ceremonial bon voyage from the society that came to love him, he then scampers out of the woods and escapes back to the comforts of society with Nathan’s French mistress. In the end, is the point that we’re all rubes and hypocrites?

The other disappointing aspect to Human Nature is as I declared in 2002, it feels like quirky for quirky’s sake screenwriting. Kaufman has become a screenwriting legend and he’s able to marry absurd, bizarre, and dangerous elements into meaningful and subversive and satirical masterstrokes, but the man cannot be expected to perform at the highest heights every time. Human Nature is stuffed full of wacky moments and wacky characters and it doesn’t feel like it ever amounts to more than the sum of its transitory parts. In contrast, 2022’s Everything Everywhere All At Once is an example of how one can take the most bizarre ideas and still find ways to tie them back in meaningful ways that braid into the larger theme. However, much of Human Nature feels like a quirk dartboard being hit over and over, a catalog of strange visuals and goofy ideas (Lila breaks out into song!) that fails to coalesce into a larger thesis like an Adaptation or an Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind or the vastly underrated Synecdoche, New York, Kaufman’s directorial debut. He’s a master of the idiosyncratic, but Human Nature suffers because ultimately what does it have to say? Puff is set up for ridicule. Nathan is set up for ridicule. Even Lila is set up, though for murder. In the end, when Puff returns to the wild in a public galivanting that feels like a ceremonial bon voyage from the society that came to love him, he then scampers out of the woods and escapes back to the comforts of society with Nathan’s French mistress. In the end, is the point that we’re all rubes and hypocrites?

This was Gondry’s first film and it feels like a training vehicle for what would be his real masterpiece, 2004’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, one of my favorite films ever. Gondry’s style is still recognizable, especially reminiscent of his tactile, kitschy, avant garde music videos he directed for Bjork, the queen of weird 1990s music videos. Gondry’s hardscrabble, idiosyncratic style was a natural match with Kaufman’s vivid imagination. It’s surprising that they never reunited after Eternal Sunshine. Gondry had a few movies (2006’s The Science of Sleep, 2008’s Be Kind Rewind) but they felt lacking, trifling without a stronger writer to guide and ground them in human drama. Gondry even tried his hand at studio action to middling results with 2010’s The Green Hornet. He mostly retreated back to music videos and commercials and had a short lived series on Showtime with Jim Carrey as a former children’s TV entertainer whose fantasy is blending with reality. It seemed like a good fit for Gondry, and a nice starring role for Carrey, but it was canceled after two seasons. Even the realm of music videos seems so far removed now, where Hollywood was snatching up every visual virtuoso.

Human Nature has plenty of familiar faces, no doubt eager to attach their names to a daring Kaufman movie. Arquette is winning and the best part of the movie. She would later win an Academy Award for her decade-in-the-making performance in Richard Linklater’s Boyhood. Now I enjoy her in a chilly, villainous role as the shady corporate boss on Apple TV’s stunning sci-fi satire, Severance. Robbins is officious to a fault here. He too would later win an Oscar for 2003’s Mystic River. Poor Ifans, so big after his scene-stealing role in 1999’s Notting Hill, who never seemed to capitalize on his success (even his Spider-Man villain got the weakest treatment in No Way Home). He’s had a long career and prominent TV roles with Berlin Station and the Game of Thrones prequel series, House of the Dragon. I did laugh out loud at his “yahoo” after being zapped by his electric shock collar. You’ll also see Rosie Perez, Peter Dinklage, Robert Forster, Toby Huss, Hillary Duff, and Mary Kay Place. As I said in 2002, acting is not the problem with Human Nature. It’s the writing and characterization that lets these people down.

I usually like to devote a paragraph to going back and re-evaluating my initial words from twenty years ago, but I agree with everything I wrote. Everything. That’s initially why I thought this would be a shorter review. What more am I going to say other than my initial opinion of this movie is the same opinion I have upon re-watching? With the distance, it’s even more clear to me that Human Nature is the weakest film of Kaufman’s career. Even a movie I didn’t really gel with, like 2020’s I’m Thinking of Ending Things, at least has a lot more ambition I can recognize. It’s a character study obfuscated with too much eccentric clutter but there’s still an artistic vision there, even if it didn’t work for me. Kaufman is too unique a voice to only have made three movies in the last 14 years, and it makes it even more frustrating when I don’t connect with his long-in-the-making projects. Human Nature is too limited in scope and characterization. It’s slightly interesting as a footnote to a great screenwriter but little more.

Re-Review Grade: C

I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020)

I expect strange from a Charlie Kaufman movie; that goes without saying. I also expect some high concept turned inward and, most importantly, a humane if bewildered anchor. His other movies have dealt with similar themes of depression (Anomalisa), relationship entropy (Eternal Sunshine), identity (Being John Malkovich), and regret from afar (Synecdoche, New York). However, no matter the head-spinning elements, the best Kaufman movies have always been the ones that embrace a human, if flawed, experience with sincerity rather than ironic detachment. There’s a reason that Eternal Sunshine is a masterpiece and that nobody seems to recall 2002’s Human Nature (ironic title for this reference). 2015’s Anomalisa was all about one man trying to break free from the fog of his mind, finding a woman as savior, and then slowly succumbing to the same trap. Even with its wilder aspects, it was all about human connection and disconnection. By contrast, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is all about a puzzle, and once you latch onto its predictable conclusion, it doesn’t provide much else in the way of understanding. It’s more a “so, that’s it?” kind of film, an exercise in trippy moments intended to add up to a whole, except it didn’t add up for me. I held out hope, waiting until the very end to be surprised at some hidden genius that had escaped me, for everything to come together into a more powerful whole, like Synecdoche, New York. It didn’t materialize for me and I was left wondering why I spent two hours with these dull people.

I expect strange from a Charlie Kaufman movie; that goes without saying. I also expect some high concept turned inward and, most importantly, a humane if bewildered anchor. His other movies have dealt with similar themes of depression (Anomalisa), relationship entropy (Eternal Sunshine), identity (Being John Malkovich), and regret from afar (Synecdoche, New York). However, no matter the head-spinning elements, the best Kaufman movies have always been the ones that embrace a human, if flawed, experience with sincerity rather than ironic detachment. There’s a reason that Eternal Sunshine is a masterpiece and that nobody seems to recall 2002’s Human Nature (ironic title for this reference). 2015’s Anomalisa was all about one man trying to break free from the fog of his mind, finding a woman as savior, and then slowly succumbing to the same trap. Even with its wilder aspects, it was all about human connection and disconnection. By contrast, I’m Thinking of Ending Things is all about a puzzle, and once you latch onto its predictable conclusion, it doesn’t provide much else in the way of understanding. It’s more a “so, that’s it?” kind of film, an exercise in trippy moments intended to add up to a whole, except it didn’t add up for me. I held out hope, waiting until the very end to be surprised at some hidden genius that had escaped me, for everything to come together into a more powerful whole, like Synecdoche, New York. It didn’t materialize for me and I was left wondering why I spent two hours with these dull people.

A Young Woman (Jessie Buckley) is traveling with her boyfriend Jake (Jessie Plemons) to meet his parents for the first time. It’s snowy Oklahoma, barren, dreary, and not encouraging. In the opening line we hear our heroine divulge the title in narration, which we think means their relationship but might prove to have multiple interpretations. It only gets more awkward as she meets Jake’s parents (David Thewlis, Toni Collette) and weird things continue happening. The basement door is chained with what look like claw marks. People rapidly age. The snow keeps coming down and the Young Woman is eager to leave for home but she might not be able to ever get home.

The title is apt because I was thinking of ending things myself after an hour of this movie. Kaufman’s latest is so purposely uncomfortable that it made me cringe throughout, and not in a good squirmy way that Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster) has perfected. Kaufman wants to dwell and drag out the discomfort, starting with the relationship between Young Woman and Jake. She’s already questioning whether or not she should be meeting his parents and their inbound conversations in the car are long and punctuated by Jake steering them into proverbial dead ends. He’s a dolt. You clearly already don’t feel a connection between them, and this is then extended into the family meet and dinner, which takes up the first hour of the movie. I’m Thinking of Ending Things tips its hand early about not trusting our senses and that we are in the realm of an unreliable narrator. Characters will suddenly shift placement in the blink of an eye, like we blacked out, and character names, professions, histories, and even ages will constantly alter. The Young Woman is a theoretical physicist, then a gerontologist, then her “meet cute” with Jake borrows liberally from a rom-com directed by Robert Zeemckis in this universe (my one good laugh). Jake’s parents will go from old to young and young to old without comment. All the surreal flourishes keep your attention, at least for the first half, as we await our characters to be affected by their reality, but this never really happens. Our heroine feels less like our protagonist (yes, I know there’s a reason for this) because her responses to the bizarre are like everyone else. The entire movie feels like a collection of incidents that could have taken any order, many of which could also have been left behind considering the portentous 135-minute running time.

The title is apt because I was thinking of ending things myself after an hour of this movie. Kaufman’s latest is so purposely uncomfortable that it made me cringe throughout, and not in a good squirmy way that Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster) has perfected. Kaufman wants to dwell and drag out the discomfort, starting with the relationship between Young Woman and Jake. She’s already questioning whether or not she should be meeting his parents and their inbound conversations in the car are long and punctuated by Jake steering them into proverbial dead ends. He’s a dolt. You clearly already don’t feel a connection between them, and this is then extended into the family meet and dinner, which takes up the first hour of the movie. I’m Thinking of Ending Things tips its hand early about not trusting our senses and that we are in the realm of an unreliable narrator. Characters will suddenly shift placement in the blink of an eye, like we blacked out, and character names, professions, histories, and even ages will constantly alter. The Young Woman is a theoretical physicist, then a gerontologist, then her “meet cute” with Jake borrows liberally from a rom-com directed by Robert Zeemckis in this universe (my one good laugh). Jake’s parents will go from old to young and young to old without comment. All the surreal flourishes keep your attention, at least for the first half, as we await our characters to be affected by their reality, but this never really happens. Our heroine feels less like our protagonist (yes, I know there’s a reason for this) because her responses to the bizarre are like everyone else. The entire movie feels like a collection of incidents that could have taken any order, many of which could also have been left behind considering the portentous 135-minute running time.

There are a lot of weird moments and overall this movie will live on in my memory only for its moments. We have a lengthy choreographed dance with doubles for Jake and the Young Woman, an animated commercial for ice cream, an acceptance speech directly cribbed from A Beautiful Mind that then leads directly into a performance from Oklahoma!, an entire resuscitation of poetry and a film review by Pauline Kael, talking ghosts, and more. It’s a movie of moments because every item is meant to be a reflection of one purpose, but I didn’t feel like that artistic accumulation gave me better clarity. There’s solving the plot puzzle of what is happening, the mixture of the surreal with the everyday, but its insight is limited and redundant. The film’s conclusion wants to reach for tragedy but it doesn’t put in the work to feel tragic. It’s bleak and lonely but I doubt that the characters will resonate any more than, say, an ordinary episode of The Twilight Zone. Everything is a means to an ends to the mysterious revelation, which also means every moment has the nagging feeling of being arbitrary and replaceable. The second half of this movie, once they leave the parents’ home, is a long slog that tested my endurance.

Buckley (HBO’s Chernobyl) makes for a perfectly matched, disaffected, confused, and plucky protagonist for a Kaufman vehicle. She has a winsome matter of a person trying their best to cover over differences and awkwardness without the need to dominate attention. Her performance is one of sidelong glances and crooked smiles, enough to impart a wariness as she descends on this journey. Buckley has a natural quality to her, so when her character stammers, stumbling over her words and explanations, you feel her vulnerability on display. After Wild Rose and now this, I think big things are ahead for Buckley. The other actors do credible work with their more specifically daft and heightened roles, mostly in low-key deadpan with the exception of Collette (Hereditary), who is uncontrollably sharing and crying. It’s a performance that goes big as a means of creating alarm and discomfort and she succeeds in doing so.

Buckley (HBO’s Chernobyl) makes for a perfectly matched, disaffected, confused, and plucky protagonist for a Kaufman vehicle. She has a winsome matter of a person trying their best to cover over differences and awkwardness without the need to dominate attention. Her performance is one of sidelong glances and crooked smiles, enough to impart a wariness as she descends on this journey. Buckley has a natural quality to her, so when her character stammers, stumbling over her words and explanations, you feel her vulnerability on display. After Wild Rose and now this, I think big things are ahead for Buckley. The other actors do credible work with their more specifically daft and heightened roles, mostly in low-key deadpan with the exception of Collette (Hereditary), who is uncontrollably sharing and crying. It’s a performance that goes big as a means of creating alarm and discomfort and she succeeds in doing so.

I know there will be people that enjoy I’m Thinking of Ending Things and its surreal, sliding landscape of strange ideas and images. Kaufman is a creative mind like few others in the industry and I hope this is the start of an ongoing relationship with Netflix that affords more of his stories to make their way to our homes. This is only the second movie he’s written to be produced in the last decade, and that’s far too few Kaufman movies to my liking. At the same time, I’m a Kaufman fan and this one left me mystified, alienated, and simply bored. I imagine a second viewing would provide me more help finding parallels and thematic connections, but honestly, I don’t really want to watch this movie again. I recall 2017’s mother!, an unfairly derided movie that was also oft-putting and built around decoding its unsubtle allegory. That movie clicked for me once I attuned myself to its central conceit, and it kept surprising me and horrifying me. It didn’t bore me, and even its indulgences felt like they had purpose and vision. I guess I just don’t personally get that same feeling from I’m Thinking of Ending Things. It’s a movie that left me out cold.

Nate’s Grade: C

Anomalisa (2015)

It’s been seven long years since the last Charlie Kaufman movie graced our screens. Cinema needs a voice as wonderfully strange and intelligent as Kaufman’s, and if it wasn’t for a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2012, we might have had to wait even longer. The stop-motion animated film Anomalisa is one of Kaufman’s most accessible movies and it involves felt puppets. Think about that for a second.

It’s been seven long years since the last Charlie Kaufman movie graced our screens. Cinema needs a voice as wonderfully strange and intelligent as Kaufman’s, and if it wasn’t for a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2012, we might have had to wait even longer. The stop-motion animated film Anomalisa is one of Kaufman’s most accessible movies and it involves felt puppets. Think about that for a second.

Michael Stone (voiced by David Thewlis) is a successful motivational speaker traveling to Cincinnati for a brief conference. He’s supposed to give a keynote speech on the importance of treating the customer like they are special; however, Michael is trapped in a purgatory of redundancy. Every other human being looks the same and sounds the same (all voiced by Tom Noonan), even Michael’s wife and young son. Then he hears a voice that breaks from the conformity of Noonan’s vocal chords. The voice belongs to Lisa (voiced by Jennifer Jason-Leigh), an unassuming and unabashed fan of Stone. She’s bright and lively but guarded due to a facial burn that hampers her self-esteem. She’s eager to spend time with Michael and confused when he insists on spending more time with her. Men usually gravitate to Lisa’s more carefree and forward friend. Not her. Over the course of that night, Michael and Lisa navigate one another. He’s fascinated to hear a new voice and wants to know all he can about her. She’s flattered with the sincere consideration. Michael only wants to be with Lisa from now on, but this decision will have consequences and it feels like there is an invisible force fighting against their union.

I still can’t shake the fact that there seems little reason for this movie to be animated. Perhaps it’s the fact that it started as an oral play, but the use of the animation medium and everything it can provide so rarely feels utilized. The repeated faces of all the other humdrum human beings in the world, that wider-eyed gnome-like face, is a fine touch but the same could be accomplished through rudimentary computer effects now. Hell, Kaufman’s own Being John Malkovich achieved this in a memorable scene and that was over 16 years ago. I won’t pretend to know the economics of the animation industry but I just assume anything as time-consuming and precise is going to be pricey (reportedly the budget was $8 million). I thought of money during the first thirty minutes. It’s almost like a bet, as if Kaufman and co-director Duke Johnson (TV’s Frankenhole, Community) were trying to animate the banality of a business trip just because nobody has ever done it before. Here are a short list of other things, I assume, have escaped being replicated in animated form: waiting in line at the DMV, looking for a lost TV remote, cleaning one’s ears, watching the Republican presidential debates, changing the toilet paper roll, and filling out the iTunes user agreement. Would any of these banal acts deserve to be animated? Probably not, but I’m sure that’s the point for Kaufman and Johnson. For the longest time we’re meant to live the empty existence of Michael Stone and so we spend thirty minutes making pained small talk, checking into a sterile hotel room, calling loved ones, reconnecting with an ex, and visiting a sex shop in a drunken haze. My friend Ben Bailey asked the same question at five-minute junctions: “Is anything going to happen?”

I still can’t shake the fact that there seems little reason for this movie to be animated. Perhaps it’s the fact that it started as an oral play, but the use of the animation medium and everything it can provide so rarely feels utilized. The repeated faces of all the other humdrum human beings in the world, that wider-eyed gnome-like face, is a fine touch but the same could be accomplished through rudimentary computer effects now. Hell, Kaufman’s own Being John Malkovich achieved this in a memorable scene and that was over 16 years ago. I won’t pretend to know the economics of the animation industry but I just assume anything as time-consuming and precise is going to be pricey (reportedly the budget was $8 million). I thought of money during the first thirty minutes. It’s almost like a bet, as if Kaufman and co-director Duke Johnson (TV’s Frankenhole, Community) were trying to animate the banality of a business trip just because nobody has ever done it before. Here are a short list of other things, I assume, have escaped being replicated in animated form: waiting in line at the DMV, looking for a lost TV remote, cleaning one’s ears, watching the Republican presidential debates, changing the toilet paper roll, and filling out the iTunes user agreement. Would any of these banal acts deserve to be animated? Probably not, but I’m sure that’s the point for Kaufman and Johnson. For the longest time we’re meant to live the empty existence of Michael Stone and so we spend thirty minutes making pained small talk, checking into a sterile hotel room, calling loved ones, reconnecting with an ex, and visiting a sex shop in a drunken haze. My friend Ben Bailey asked the same question at five-minute junctions: “Is anything going to happen?”

Once Lisa is introduced, the movie finds its footing and purpose and it is a relief. Maybe that was Kaufman and Johnson’s design so that we, the audience, would also feel the same elation. The rest of the movie is watching a love affair, two people coming into one another’s orbit. The dialogue exchanges are very natural and slowly reveal different layers of the characters, mostly Lisa. Michael is intoxicated and demurs often, instead only wanting to hear the sweet sound of her voice. There’s a delicious irony to Michael working in customer service, an industry that is often listening to people’s angry voices over phone lines, and his inability to distinguish speech. Instantly we get a strong understanding of just how desperate Michael is to form a real connection. It’s his fawning attention that allows Lisa to allow herself to be vulnerable and assertive. In one of the most realistic sex scenes ever captured in movies, Lisa communicates what she wants and what provides her satisfaction, and Michael dutifully abides, determined to hear the sounds of her wonderful voice reach climactic degrees of pleasure. The love scene has garnered plenty of press just for the fact that it’s an animated film and our two characters are fully rendered, though this goes beyond just having recognizable parts. The way the bodies move, the way the lines and creases fold, the way people react to the inherent awkwardness of sexual congress, it’s all faithfully recreated and done so without a hint of comedy. This is by no means the raucous copulation from Team America. It’s a surprisingly touching moment as these two characters simply connect on a few levels.

It’s after the sex scene that everything changes. I’ll forego spoilers and say that there’s a certain buyer’s remorse when it comes to impulsive love affairs, and trying to maintain that same feeling of ecstasy can be like chasing a drug that requires more and more of oneself. There’s a very interesting transition that brilliantly illustrates Michael’s anguish. The conclusion is at once inevitable, hopeful, and also despairing. That’s because it opens up the world in a new way and provides further examination on Michael and the consequences of his crushing depression. The core of the movie is about the need for human connection. I wouldn’t cite Kaufman as a romantic but he does prioritize human connection and believes in the power of those fleeting moments. Aren’t we all looking for our own anomaly, someone whose voice slices through the din? Once those moments run their course, some of us grieve and some of us ascend, made stronger and more complete from the sum total of those magical experiences. The ending provides a new lens to interpret the movie, though most viewers will have already suspected given the mundane prison of the world onscreen. It’s not exactly a twist ending but more a confirmation that Michael Stone is personalizing his misery and unable to escape it. All he can look forward to are those fleeting moments of human connection and hope.

The stop-motion animation is impressive though it seems intentional to elicit a certain strangeness. Stop-motion used to have that certain stutter-stop movement that made it wonderfully alien. With advances in technology, stop-motion can now look as seamlessly animated as other forms of the medium, as evidenced by the wonderful Laika releases like The Box Trolls and ParaNorman. Johnson and Kaufman decided to use felt dolls which allows the characters to have a certain glow to them, as if they’re emanating some internal lightness of being (apologies to Kundera). The illusion is getting easier to hide. Johnson makes the decision to show the seams of his universe. The facial marks that indicate the interchangeable partitions remain visible, making the Noonan-voiced characters look like they’re all wearing glasses. It’s an animated movie that wants to remind you it’s animated but tell a story that doesn’t need the assistance of animation. That’s one unconventional goal. I’ll admit that it did tickle me to watch the ongoing troubles of getting a room key card to work. Johnson also makes use of long takes to better communicate the reality of this world, from the mundane to the ecstasy. There’s one dream sequence that dips into more identifiable and surreal Kaufman territory, but excluding this moment the movie is mostly the ordinary fixtures of ordinary hotel rooms.

The stop-motion animation is impressive though it seems intentional to elicit a certain strangeness. Stop-motion used to have that certain stutter-stop movement that made it wonderfully alien. With advances in technology, stop-motion can now look as seamlessly animated as other forms of the medium, as evidenced by the wonderful Laika releases like The Box Trolls and ParaNorman. Johnson and Kaufman decided to use felt dolls which allows the characters to have a certain glow to them, as if they’re emanating some internal lightness of being (apologies to Kundera). The illusion is getting easier to hide. Johnson makes the decision to show the seams of his universe. The facial marks that indicate the interchangeable partitions remain visible, making the Noonan-voiced characters look like they’re all wearing glasses. It’s an animated movie that wants to remind you it’s animated but tell a story that doesn’t need the assistance of animation. That’s one unconventional goal. I’ll admit that it did tickle me to watch the ongoing troubles of getting a room key card to work. Johnson also makes use of long takes to better communicate the reality of this world, from the mundane to the ecstasy. There’s one dream sequence that dips into more identifiable and surreal Kaufman territory, but excluding this moment the movie is mostly the ordinary fixtures of ordinary hotel rooms.

Following the uniqueness of its idiosyncratic creator, Anomalisa is unlike anything else out there and an animated film that is nakedly personable and desperate to grasp for something richer and more meaningful. I can’t say that this was a story that demanded to be told through this style or animation or if it even benefits from this approach, but Kaufman’s ear for human relationships is still sharp and refined. It’s like watching a stage play that just happens to be made with felt puppets that oddly feel very real. It’s a movie that has different layers of what constitutes reality, given an extra sheen of artifice. It’s a movie that conveys the hopes and disappointments of human connection from the awkward to the mundane to the revelatory. The film does an excellent job of communicating the all-encompassing heaviness of depression, how the ordinary can be just as soul crushing and harmful. And yet the film ends not on Michael but on Lisa and on a degree of hope, that the chance encounters that mark our lives are not without consequence and benefits, aiding people to take needed steps outward. It’s a movie about the significance of human connection; something that Michael desperately spends years looking for again, to feel fully human once more, to ignite the synapses. Anomalisa is a thoughtful and touching story. I don’t know if it’s an excellent movie or an unnecessary adaptation of an innately affecting stage play, but it’s Kaufman as romantic and cynic. Who knew puppets could get so deep?

Nate’s Grade: B+

Synecdoche, New York (2008)

Nothing comes easy when dealing with acclaimed screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. The most exciting scribe in Hollywood does not tend to water down his stories. Kaufman’s latest head-trip, Synecdoche, New York, is a polarizing work that follows a nontraditional narrative and works on a secondary existential level. That’s enough for several critics to hurtle words like “incomprehensible” and “confusing” as weapons intended to marginalize Synecdoche, New York as self-indulgent prattle. I guess no one wants to go to the movies and think any more. Thinking causes headaches, after all.

Nothing comes easy when dealing with acclaimed screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. The most exciting scribe in Hollywood does not tend to water down his stories. Kaufman’s latest head-trip, Synecdoche, New York, is a polarizing work that follows a nontraditional narrative and works on a secondary existential level. That’s enough for several critics to hurtle words like “incomprehensible” and “confusing” as weapons intended to marginalize Synecdoche, New York as self-indulgent prattle. I guess no one wants to go to the movies and think any more. Thinking causes headaches, after all.

Caden (Phillip Seymour Hoffman) is a struggling 40-year-old theater director trying to find meaning in his beleaguered life. His wife (Catherine Keener) has run off to Germany with his little daughter, Olive. He also manages to botch a potential romance with Hazel (Samantha Morton), a woman who works in the theater box-office who has an unusual crush on Caden. He’s also plagued by numerous mysterious health ailments that only seem to multiply. While his life seems to be in the pits, Caden is offered a theater grant of limitless money. He has big ambitions: he will restage every moment of his whole life to try and discover the hard truths about life and death. Caden must then cast actors to portray the various people in his life. Sammy (Tom Noonan) argues that no other actor could get closer to the truth of Caden; Sammy has been following and studying Caden for over 20 years (don’t bother asking why in a movie like this). Caden also casts his new wife, Claire (Michelle Williams), as herself. The theater production gets more and more complex, eventually requiring the “Caden” character to hire his own Caden actor. Caden hires Hazel to be his assistant and Sammy falls in love with her. Caden admonishes his actor, “That Hazel isn’t for you.” Caden then tries sleeping with “Hazel” (Emily Watson) to get even with the real Hazel. By producing a theatrical mechanism that almost seems self-sustaining, Caden wants to leave his mark on the world and potentially live forever.

I heard plenty of blather about how mind-numbing Synecdoche, New York was and how Kaufman had really done it this time when he composed a script that involves characters playing characters playing characters. People told me that it was all too much to keep track of and that it made their brains hurt. The movie is complex, yes, and demands a viewer to be actively engaged, but the movie is far from confusing and any person or critic that just throws up their hands and says, “Nope, too much to think about,” is doing their brain a disservice. The movie is relatively easy to follow in a simple linear cause-effect manner; Kaufman only really goes as deep as two iterations from reality, meaning that Caden has his initial doppelganger and then eventually that doppelganger must get his own Caden doppelganger (it’s not nearly as confusing as it sounds if you see it). Now, where the movie might be tricky to understand is how deeply contemplative and metaphorical it can manage to be, especially at its somber close. That doesn’t mean that Synecdoche, New York is impossible to understand only that it requires some extra effort to appreciate. But this movie pays off in huge ways on repeat viewings, adding texture to Kaufman’s intricately plotted big picture, unfolding into a richer statement about the nature of life and death and love.

I heard plenty of blather about how mind-numbing Synecdoche, New York was and how Kaufman had really done it this time when he composed a script that involves characters playing characters playing characters. People told me that it was all too much to keep track of and that it made their brains hurt. The movie is complex, yes, and demands a viewer to be actively engaged, but the movie is far from confusing and any person or critic that just throws up their hands and says, “Nope, too much to think about,” is doing their brain a disservice. The movie is relatively easy to follow in a simple linear cause-effect manner; Kaufman only really goes as deep as two iterations from reality, meaning that Caden has his initial doppelganger and then eventually that doppelganger must get his own Caden doppelganger (it’s not nearly as confusing as it sounds if you see it). Now, where the movie might be tricky to understand is how deeply contemplative and metaphorical it can manage to be, especially at its somber close. That doesn’t mean that Synecdoche, New York is impossible to understand only that it requires some extra effort to appreciate. But this movie pays off in huge ways on repeat viewings, adding texture to Kaufman’s intricately plotted big picture, unfolding into a richer statement about the nature of life and death and love.

Theater has often been an easy metaphor for life. William Shakespeare said, “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts.” Kaufman movies always dwell substantially with the nature of identity, and Synecdoche, New York views identity through the artifice of theater. Caden searches for something brutal and true via the stage, but of course eventually his search for truth becomes compromised with personal interests. Characters in Caden’s life are altered and in the end when Caden steps down, as himself, reality starts getting revised. The truth is often blurred through the process of interpretation. Caden ends up swapping identities with a bit player in the story of his life, potentially finding a greater sense of personal comfort as someone else. Don’t we all play characters in our lives? Don’t we all assume different identities for different purposes? Do we act differently at a job than at home, at church than at a bar? Caden remarks that there are no extras in life and that everyone is a lead in his or her own story.

Kaufman’s movie is also funny, like really darkly funny and borderline absurdist to the point of being some strange lost work by Franz Kafka (Hazel even mentions she’s reading Kafka’s The Trial). You may be so caught up trying to render the complexities of the story to catch all of the humor. The movie exists in a surreal landscape, where the characters treat the fantastic practically as mundane. Hazel’s house is constantly on fire and yet none of the characters regard this as dangerous or out of the ordinary. It is just another factor of life. The entire subplot with Hope Davis as a hilariously incompetent therapist is deeply weird. Caden suffers some especially cruel Job-like exploits, particularly what befalls his estranged daughter, Olive. He’s obsessed with her hidden whereabouts and European upbringing, to the point that Caden cannot even remember the name of his other daughter he has with Claire. There is a deathbed scene between the two that is equally sad and twisted given the astounding behavior that Caden is forced to apologize for. There are running gags that eventually transform into metaphors, like Caden’s many different medical ailments and the unhelpful bureaucratic doctors who know nothing and refuse to divulge any info. Kaufman even has Emily Watson, an actress mistaken for Morton, play the character of “Hazel.”

Kaufman’s movie is also funny, like really darkly funny and borderline absurdist to the point of being some strange lost work by Franz Kafka (Hazel even mentions she’s reading Kafka’s The Trial). You may be so caught up trying to render the complexities of the story to catch all of the humor. The movie exists in a surreal landscape, where the characters treat the fantastic practically as mundane. Hazel’s house is constantly on fire and yet none of the characters regard this as dangerous or out of the ordinary. It is just another factor of life. The entire subplot with Hope Davis as a hilariously incompetent therapist is deeply weird. Caden suffers some especially cruel Job-like exploits, particularly what befalls his estranged daughter, Olive. He’s obsessed with her hidden whereabouts and European upbringing, to the point that Caden cannot even remember the name of his other daughter he has with Claire. There is a deathbed scene between the two that is equally sad and twisted given the astounding behavior that Caden is forced to apologize for. There are running gags that eventually transform into metaphors, like Caden’s many different medical ailments and the unhelpful bureaucratic doctors who know nothing and refuse to divulge any info. Kaufman even has Emily Watson, an actress mistaken for Morton, play the character of “Hazel.”

This is Kaufman’s debut as a director and I think the movie ultimately benefits by giving its writer more control over the finished product. The movie is such a singular work of creativity that it helps by not having another director; there is no other artistic vision but Kaufman’s. While the film can feel slightly hermetic at times visually, Kaufman and cinematographer Frederick Elmes (The Ice Storm) pack the film with detail. Stylistically, the film is mannered but this is to make maximum impact for the vast amount of visual metaphors. Synecdoche, New York never feels as mannered as the recent Wes Anderson films, henpecked by a style that serves decoration rather than storytelling. The production design for the world-within-a-world is also alluring and imaginative, like a living, breathing dollhouse.

The assorted actors do well with their quirky, flawed characters, but clearly Hoffman is the linchpin to the film. He plays a character from middle age to old age, and at every step Hoffman manages to infuse some level of empathy for a man routinely disappointed by his own life. The failed yet lingering and hopeful romance between Caden and Hazel provides an almost sweet undercurrent for a character obsessed with death. Hoffman is convincing at every moment, even as a hobbled 80-year-old man, and gives a performance steeped in sadness but with the occasional glimmer of hope, whether it be the ambition of his theater project or the dream of holding Hazel once more. Morton is also wonderfully kindhearted and endearing as the woman that just seems to keep slipping away from Caden.

The assorted actors do well with their quirky, flawed characters, but clearly Hoffman is the linchpin to the film. He plays a character from middle age to old age, and at every step Hoffman manages to infuse some level of empathy for a man routinely disappointed by his own life. The failed yet lingering and hopeful romance between Caden and Hazel provides an almost sweet undercurrent for a character obsessed with death. Hoffman is convincing at every moment, even as a hobbled 80-year-old man, and gives a performance steeped in sadness but with the occasional glimmer of hope, whether it be the ambition of his theater project or the dream of holding Hazel once more. Morton is also wonderfully kindhearted and endearing as the woman that just seems to keep slipping away from Caden.

There’s no other way to say it but Synecdoche, New York is a movie that you need to see multiple times to appreciate. The plot is so grandiose in scope and ambition that one sitting does not do it justice. Kaufman has forged a strikingly peculiar movie that manages to be surreal and bleakly comic while also being poignant and humane. This is a big movie with big statements that can be easily missed, but for those willing to dig into the wealth of metaphor and reflection, Synecdoche, New York is a rewarding film experience that sticks with you. By the end of this movie, Kaufman has earned the merging of metaphor and narrative. I have already seen the movie twice and still cannot get it out of my thoughts. This isn’t the kind of movie that you feel warm affection for, like Kaufman’s blissfully profound Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. This movie is less a confounding puzzle than an intellectually stimulating examination on art, the human experience, and, ultimately death. If people would rather kill brain cells watching whatever dreck Hollywood secretes every week (cough, Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun-Li, cough) then that’s their prerogative. Give me a Charlie Kaufman movie and a bottle of aspirin any day.

Nate’s Grade: A

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

No other movie this year captured the possibility of film like Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman’s enigmatic collaboration. Eternal Sunshine was a mind-bending philosophical excursion that also ended up being one of the most nakedly realistic romances of all time. Joel (Jim Carrey restrained) embarks on having his memories erased involving the painful breakup of Clemintine (Kate Winslet, wonderful), an impulsive woman whose vibrant hair changes as much as her moods. As Joel revisits his memories, they fade and die. He starts to fall in love with her all over again and tries to have the process stop. This labyrinth of a movie gets so many details right, from the weird physics of dreams to the small, tender moments of love and relationships. I see something new and marvelous every time I watch Eternal Sunshine, and the fact that it’s caught on with audiences (it was nominated for Favorite Movie by the People’s friggin’ Choice Awards) reaffirms its insights into memory and love. I never would have thought we’d get the perfect romance for the new millennium from Kaufman. This is a beautiful, dizzingly complex, elegant romance caked in visual grandeur, and it will be just as special in 5 years as it will be in 50, that is if monkeys don’t evolve and take over by then (it will happen).

No other movie this year captured the possibility of film like Michel Gondry and Charlie Kaufman’s enigmatic collaboration. Eternal Sunshine was a mind-bending philosophical excursion that also ended up being one of the most nakedly realistic romances of all time. Joel (Jim Carrey restrained) embarks on having his memories erased involving the painful breakup of Clemintine (Kate Winslet, wonderful), an impulsive woman whose vibrant hair changes as much as her moods. As Joel revisits his memories, they fade and die. He starts to fall in love with her all over again and tries to have the process stop. This labyrinth of a movie gets so many details right, from the weird physics of dreams to the small, tender moments of love and relationships. I see something new and marvelous every time I watch Eternal Sunshine, and the fact that it’s caught on with audiences (it was nominated for Favorite Movie by the People’s friggin’ Choice Awards) reaffirms its insights into memory and love. I never would have thought we’d get the perfect romance for the new millennium from Kaufman. This is a beautiful, dizzingly complex, elegant romance caked in visual grandeur, and it will be just as special in 5 years as it will be in 50, that is if monkeys don’t evolve and take over by then (it will happen).

Nate’s Grade: A

Human Nature (2002)

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman jumped on to Hollywood’s A-list when his feature debut Being John Malkovich was unleashed in 1999. Malkovich was a brilliant original satire on identity, be it celebrity or sexual, and was filled with riotous humor but also blended beautifully with a rich story that bordered on genius that longer it went. Now Kaufman tries his hand expounding at the meaning of civilization versus animal instinct in Human Nature. As one character tells another, “Just remember, don’t do whatever your body is telling you to do and you’ll be fine.”

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman jumped on to Hollywood’s A-list when his feature debut Being John Malkovich was unleashed in 1999. Malkovich was a brilliant original satire on identity, be it celebrity or sexual, and was filled with riotous humor but also blended beautifully with a rich story that bordered on genius that longer it went. Now Kaufman tries his hand expounding at the meaning of civilization versus animal instinct in Human Nature. As one character tells another, “Just remember, don’t do whatever your body is telling you to do and you’ll be fine.”

Lila (Patricia Arquette) is a woman burdened with excessive body hair ever since she was old enough for a training bra (with the younger version played by Disney’s Lizzie McGuire). Lila feels ashamed by her body and morbidly humiliated. She runs away to the forest to enjoy a life free from the critical eyes of other men. Here she can commune with nature and feel that she belongs.

Nathan (Tim Robbins) is an anal retentive scientist obsessed with etiquette. As a young boy Nathan was sent to his room for picking the wrong fork to eat his meal with. He is now trying his best to teach mice table manners so he can prove that if etiquette can be taught to animals it can be ingrained toward humanity.Lila and Nathan become lovers when she ventures back into the city, eliminating her body hair for now, because of something infinitely in human nature – hormones. The two of them find a form of content, as neither had known the intimate touch of another human being.“Puff” (Rhys Ifans) is a grown man living his life in the woods convinced by his father that he is an ape. One day while walking through the woods Nathan and Lila discover the ape-man and have differing opinions on what should be done with him. Nathan is convinced that he should be brought into civilization and be taught the rules, etiquette and things that make us “human.” It would also be his greatest experiment. Lila feels that he should maintain his freedom and live as he does in nature, how he feels he should.

Nathan (Tim Robbins) is an anal retentive scientist obsessed with etiquette. As a young boy Nathan was sent to his room for picking the wrong fork to eat his meal with. He is now trying his best to teach mice table manners so he can prove that if etiquette can be taught to animals it can be ingrained toward humanity.Lila and Nathan become lovers when she ventures back into the city, eliminating her body hair for now, because of something infinitely in human nature – hormones. The two of them find a form of content, as neither had known the intimate touch of another human being.“Puff” (Rhys Ifans) is a grown man living his life in the woods convinced by his father that he is an ape. One day while walking through the woods Nathan and Lila discover the ape-man and have differing opinions on what should be done with him. Nathan is convinced that he should be brought into civilization and be taught the rules, etiquette and things that make us “human.” It would also be his greatest experiment. Lila feels that he should maintain his freedom and live as he does in nature, how he feels he should.

What follows is a bizarre love triangle over the reeducation of “Puff,” as Nathan’s slinky French assistant Gabrielle (Miranda Otto) names him. Lila is torn over the treatment of Puff and also her own society induced shame of her abundant amount of body hair. Nathan feels like he is saving Puff from his wayward primal urges, as he himself becomes a victim of them when he starts having an affair with Gabrielle. Puff, as he tells a congressional committee, was playing their game so he could find some action and “get a piece of that.”

Kaufman has written a movie in the same vein as Being John Malkovich but missing the pathos and sadly, the humor. ‘Human Nature’ tries too hard to be funny and isn’t nearly as funny as it thinks it is. Many quirky elements are thrown out but don’t have the same sticking power as Kaufman’s previous film. It’s a fine line between being quirky just for quirky’s sake (like the atrocious Gummo) and turning quirky into something fantastic (like Rushmore or Raising Arizona). Human Nature is too quirky for its own good without having the balance of substance to enhance the weirdness further. There are many interesting parts to this story but as a whole they don’t ever seriously gel.

Kaufman has written a movie in the same vein as Being John Malkovich but missing the pathos and sadly, the humor. ‘Human Nature’ tries too hard to be funny and isn’t nearly as funny as it thinks it is. Many quirky elements are thrown out but don’t have the same sticking power as Kaufman’s previous film. It’s a fine line between being quirky just for quirky’s sake (like the atrocious Gummo) and turning quirky into something fantastic (like Rushmore or Raising Arizona). Human Nature is too quirky for its own good without having the balance of substance to enhance the weirdness further. There are many interesting parts to this story but as a whole they don’t ever seriously gel.

Debut director Michel Gondry cut his teeth in the realm of MTV making surreal videos for Bjork and others (including the Lego animated one for The White Stripes). He also has done numerous commercials, most infamously the creepy-as-all-hell singing navels Levi ad. Gondry does have a vision, and that vision is “Copy What Spike Jonze Did As Best as Possible.” Gondry’s direction never really registers, except for some attractive time shifts, but feels more like a rehash of Jonze’s work on; yep you guessed it, Being John Malkovich.

Arquette and Robbins do fine jobs in their roles with Arquette given a bit more, dare I say it more, humanity. Her Lila is trapped between knowing what is true to herself and fitting in to a society that tells her that it’s unhealthy and wrong. Ifans has fun with his character and lets it show. The acting in Human Nature is never really the problem.

While Human Nature is certainly an interesting film (hey it has Arquette singing a song in the buff and Rosie Perez as an electrologist) but the sum of its whole is lacking. It’s unfair to keep comparing it to the earlier Malkovich but the film is trying too hard to emulate what made that movie so successful. Human Nature just doesn’t have the gravity that could turn a quirky film into a brilliant one.

Nate’s Grade: C+

Being John Malkovich (1999)

I think I’ll simply surmise the emphasis of this review in one opening sentence: The most refreshingly and exhilarating original movie in years. MTV music video chief royale Spike Jonze directs a modern day fable that is a hallucinatory trip through the looking glass and into man’s thirst for celebrity. While Malkovich is stuffed with enough brilliant gags to kill the Austin Powers franchise, it is also a deeply articulate and insightful piece about the longing for love and fame. The movie is often thought-provoking while side-splitingly hilarious.

I think I’ll simply surmise the emphasis of this review in one opening sentence: The most refreshingly and exhilarating original movie in years. MTV music video chief royale Spike Jonze directs a modern day fable that is a hallucinatory trip through the looking glass and into man’s thirst for celebrity. While Malkovich is stuffed with enough brilliant gags to kill the Austin Powers franchise, it is also a deeply articulate and insightful piece about the longing for love and fame. The movie is often thought-provoking while side-splitingly hilarious.

I will not spill one lick of Charlie Kaufman’s plot to ensure the viewing audience the pleasure of astute surprise, and there is plenty. Malkovich is the first film in a long time to have just as many unexpected twists and turns in the final 30 minutes as it does in the first 30 minutes. The acting is wonderful consisting of John Cusack’s greasy puppeteer loser, to Cameron Diaz’s frumpy animal loving wife, to Catherine Keener’s man-eating ice queen, to even a wonderful inspired parody of John Malkovich as himself playing himself.

Being John Malkovich isn’t afraid to tackle weighty subjects such as gender identity or the hunger to be somebody, but it never looks down upon the characters or the audience but instead treats each with nurturing respect. The movie is a breeze of fresh air in a field cluttered with too many formulaic fluff appealing to mass audiences and consumer goods. Malkovich is destined to become a cult classic and deservedly so. The flick is a spurt of creative madness bordering on genius that one wonders how it ever made it into release with today’s society and studio heads. God bless you Spike Jonze and you too Charlie Kaufman. Fare thee well.

Nate’s Grade: A

You must be logged in to post a comment.